Abstract

Human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) derived from the fetal cortex can be expanded in vitro and genetically modified through lentiviral transduction to secrete growth factors shown to have a neurotrophic effect in animal models of neurological disease. hNPCs survive and mature following transplantation into the central nervous system of large and small animals including the rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Here we report that hNPCs engineered to express glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) survive long-term (7.5 months) following transplantation into the spinal cord of athymic nude rats and continue to secrete GDNF. Cell proliferation declined while the number of astrocytes increased, suggesting final maturation of the cells over time in vivo. Together these data show that GDNF-producing hNPCs may be useful as a source of cells for long-term delivery of both astrocytes and GDNF to the damaged central nervous system.

Keywords: astrocytes, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, neural progenitor cells, spinal transplantation

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a disease in which motor neurons die due to an unknown mechanism. Two out of every 100 000 people are afflicted with ALS, summing to 35 000 people in the USA and UK alone 1. Patients suffer muscle twitching, cramping, stiffness, slurred speech, eventual paralysis, and ultimately death due to respiratory failure 2. The diseased environment within the brain and spinal cord, including endogenous astrocytes, may play a leading role in the death of the motor neurons 3–5.

Replacing the motor neurons lost in ALS to reconnect the neural circuit from the brain to the muscle is very complicated. A more practical alternative may be to protect the remaining motor neurons by introducing supportive cells and growth factors. Human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) derived from the fetal cortex can be expanded in vitro for up to 50 passages with a stable karyotype and survive following transplantation into the brain or spinal cord of rodents, pigs, and primates 6–8. Furthermore, hNPCs can be genetically modified to produce growth factors that have neuroprotective potential 9. We have previously shown that transplanting hNPCs over passage 20 yields astrocytes in vivo, providing nondiseased cells that are allogenic and neuroprotective 10–12. In addition, we have shown that hNPCs can be modified to stably secrete glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in vivo 13. This two-tiered approach using hNPCs to provide astrocytes and the neuroprotective growth factor GDNF proved sufficient to rescue the microenvironment and preserve dying motor neurons in an animal models of ALS 14,15.

We generated a master cell bank (MCB) of hNPCs under current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) that we then transduced with cGMP-grade lentivirus to create research and clinical-grade lots of hNPCs stably secreting GDNF (hNPCsGDNF). We are currently completing the first of five steps required to bring these cells to the clinic under a phase 1/2a trial. The first step is to transplant the research lot of hNPCsGDNF into wild-type and SOD1G93A rats, a transgenic model of ALS, to determine the optimal effective dose and maximum feasible dose. Next, the clinical lot of hNPCsGDNF will be used for safety, toxicity, and tumorigenicity testing in immune-compromised nude rats and for a surgical technique safety trial in Yucatan mini-pigs. The final goal is Federal Drug Administration approval to undergo an 18 patient trial of unilateral lumbar transplants with systematic clinical assessment over a 12-month period.

An obvious concern when transplanting neural stem or progenitor cells is the risk of cell overgrowth and/or tumor formation. While we have not seen tumor formation following human progenitor cell transplantation into the SOD1G93A transgenic rat, this ALS model does not allow for long-term graft characterization due to the short lifespan of diseased animals. Here, we transplanted our research grade hNPCsGDNF into the spinal cord of immunocompromised athymic nude rats and performed analysis of cell survival, proliferation, phenotype, and GDNF production at 1 month and 7.5 months post-transplantation.

Materials and methods

Derivation, expansion, and banking of hNPCs

Eight-week-old postmortem fetal tissue was collected by Dr Guido Nikkhah (Germany) with institutional review board approval by his institution and by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where the resulting cell line was generated. The intact primary cortical mantel was identified, isolated, and dissociated into a single cell suspension. The resulting hNPC line was expanded as free floating spheres, termed neurospheres, in expansion medium (Stemline Neural Stem Cell Expansion Medium, S3194; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), 100 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor (GF003-AF; EMD Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA), 10 ng/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF1010; EMD Millipore). At passage 19, a bank of cGMP-grade hNPCs, termed the MCB, was generated and cryopreserved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Waisman Center Bio-Manufacturing Facility. The MCB can be sourced to generate cGMP cell lots for experimentation and clinical transplantation. The hNPCs were dissociated using a combined enzymatic (TrypLE Select, 12563-011; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) and glass pipette mechanical dissociation strategy followed by freezing at a single cell concentration of 5.0e6 cells/ml in freezing media (Cell Freezing Medium-DMSO Serum Free, 1x, C6295; Sigma-Aldrich). Six vials of the MCB were then thawed, expanded, transduced with a cGMP-grade lenti virus-SIN-WPRE-mPGK-GDNF (Indiana University Vector Production Facility) at passage 26, further expanded and banked at passage 29 as a 382 vial research lot (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IRB 21505, IRB-SCRO 29996, 22279). The lentiviral construct encoding GDNF is characterized by the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase 1 promoter, which provides constitutive expression of GDNF, as well as post-translational cis-acting regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus (WPRE) as it has been shown to significantly enhance transgene expression.

Generation and characterization of hNPCGDNF

From the hNPC MCB, cells at passage 26 were transduced with a cGMP-grade lenti virus-SIN-WPRE-mPGK-GDNF (Indiana University Vector Production Facility) following previously described methods 9. Briefly, neurospheres were dissociated to single cells, incubated for 12 h in lentivirus at 125 ng p24 capsid protein/million cells and then fresh expansion media was added to dilute the virus. Neurospheres reaggregated within 24–48 h and stable GDNF gene expression was verified by immunocytochemistry at 1 and 5 weeks postinfection. For in vitro differentiation, cells were dissociated, plated onto laminin-coated glass coverslips for 7 days, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and then stained with antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Z0334; Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA; 1/500), GDNF (BAF212; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA; 1/250), and a DAPI nuclear counterstain (D1306; Life Technologies).

Cell preparation for transplantation

Research lot vials were thawed, rinsed with 2.6% Pulmozyme (Genentech, San Francisco, California, USA)/transplantation medium (buffer solution containing glucose), counted, centrifuged, resuspended at the appropriate transplantation concentration in transplantation media and stored on ice until completion of surgery. Cell viability before and after surgery was confirmed using trypan blue exclusion counts and by plating the cells on laminin-coated coverslips for 24 h before fixation.

Spinal transplantation of cells

Male athymic nude rats (Hsd:RH-Foxn1rnu; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) at 8 weeks (240–280 g) of age were transplanted with 2 μl of research grade hNPCGDNF in five distinct sites, 1 mm apart at a concentration of 60 000 cells/μl. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isofluorane, administered analgesic drugs (buprenorphine and carprofen), and transferred to a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, California, USA) where the 12th rib of the rat was identified and an incision was performed in the skin and muscle to expose the lumbar vertebrae. A hemilaminectomy was performed on the side of the surgery to expose the spinal cord followed by a dura incision. Cells were loaded into a 45° beveled glass micropipette connected to a 10 μl Hamilton syringe and a microinjection pump for injection directly into the parenchyma (0.8 mm mediolateral, 1.8 mm dorsoventral) at a rate of 1 μl/min. The use and maintenance of rats were performed in accordance with the Guide of Care and Use of Experimental Animals of the American Council on Animal Care and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (IACUC 4260).

Tissue collection and histology

Rats were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl and fixed with 4% PFA [1224SK-SP; Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, Pennsylvania, USA]. Tissues were collected, postfixed overnight in 4% PFA, and transferred into 30% sucrose for 48 h before sectioning (35 μm) on a sliding microtome (SM2010R; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The side contralateral to surgery was identified by notching the dorsal horn. Every 12th section sample of the lumbar spinal cord was immunostained according to standard techniques with the following Stemcells Inc. (Palo Alto, California, USA) human-specific antibodies against Ku80 (SC101, 1/200), GFAP (SC123, 1/2000), and cytoplasm (SC121, 1/2000). Antibodies against Ki67 (VP-K451; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA; 1/100), nestin (ABD69; EMD Millipore; 1/10 000), choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (AB144P; EMD Millipore; 1/200), and GDNF (BAF212; R&D Systems; 1/250) were also used. Sections were stained with fluorophore-coupled secondary antibodies Alexa-488 or Alexa-594 (multiple variants; Life Technologies; 1/1000) and counterstained with DAPI (D1306; Life Technologies) or with 3,3-diaminobenzidine peroxidase kit with nickel enhancement (SK-4100; Vector Laboratories).

Stereology and immunohistological quantifications

Stereological quantification was performed using the optical fractionator method (MBF Biosciences, Williston, Vermont, USA). For SC101/Ki67 and nestin/GFAP cell counts, the ipsilateral spinal cord sections were individually traced. SC101, Ki67, nestin, and GFAP-positive cells were counted at a ×60 magnification, with parameters of the distance between counting frames (500 μm), the counting frame size (75 μm×75 μm), the dissector height (23 μm), and the guard zone thickness (2.5 μm).

Statistical analysis

Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All counting data from immunocytochemical/histochemical analyses and cell survival were expressed as mean values±SEM and analyzed by two-tailed t-test. Differences were considered significant when P value was less than 0.05.

Results

hNPCs can be genetically modified to stably express GDNF

Following isolation from the human fetal cortex, hNPCs were expanded as neurospheres in vitro and passaged weekly using a mechanical chopping technique that permits cells to remain as a three-dimensional structure 16. hNPCs were expanded and banked until passage 26, at which time cells were infected with a clinical-grade lentivirus encoding GDNF to generate hNPCGDNF. hNPCs differentiated mainly into GFAP-expressing astrocytes, with hNPCsGDNF showing stable GDNF expression in ∼60% of the population at 5 weeks postinfection compared with noninfected hNPCs with no detectable GDNF expression (Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 1.

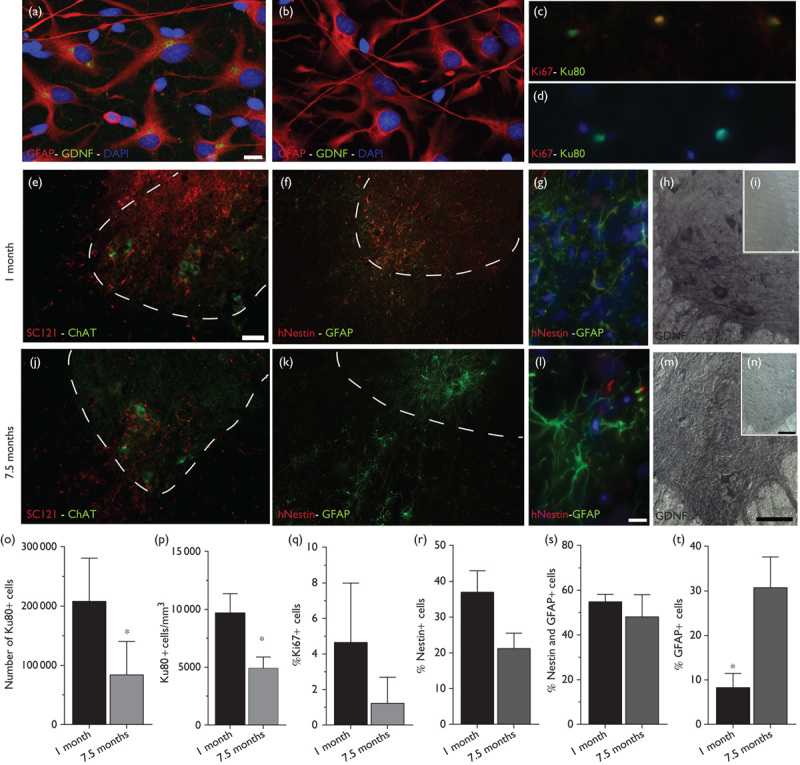

Survival, differentiation, and sustained GDNF expression following long-term transplants of hNPCs. (a, b) Immunocytochemistry following in vitro differentiation shows hNPCGDNF (a) and control hNPCs (b) express the astrocyte marker GFAP (red) but only hNPCsGDNF express GDNF (green). (c, d) High magnification image of cells expressing Ku80 (green) and Ki67 (red) at 1 month (c) and 7.5 months (d) after transplantation. (e, j) Low magnification image of human cytoplasmic marker (SC121, red) and the motor neuron marker (ChAT, green) showing appropriate targeting of the transplanted cells to the ventral horn at 1 month (e) and 7.5 months (j) after transplantation. (f, k) Low and (g, l) high magnification images of cells expressing human-specific nestin (red) and human-specific GFAP (green) at 1 month (f, g) and 7.5 months (k, l) after transplantation. Note the increased GFAP expression and changes in morphology at 7.5 months. (h, i and m, n) GDNF expression is observed ipsilateral (h, m) but not contralateral (i, n) to the transplant at 1 month (h, i) and 7.5 months (m, n) after transplantation. Note the appearance of large cells stained for GDNF, which is presumably host motor neurons taking up GDNF secreted by the transplanted cells. (o, p) Stereological quantification of cells expressing Ku80 revealed a significant decrease in the number of grafted cells (o) and in cell density (p) at 1 month compared with 7.5 months after transplantation. (q) No significant difference in cell proliferation was observed at 1 month compared with 7.5 months after transplantation. (r–t) Quantification of cells expressing nestin and GFAP showed no difference in nestin expression (r, s) but a significant increase in GFAP-expressing cells at 7.5 months compared with 1 month after transplantation (t). Scale bars: (a)–(d), (g), (l), 10 μm; (e) and (f), (j) and (k), 75 μm; (h), (i), (m), (n), 100 μm. ChAT, choline acetyltransferase; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; hNPCs, human neural progenitor cells. *P<0.05.

Survival, differentiation, and sustained GDNF expression in long-term transplants

hNPCGDNF were transplanted directly into the spinal parenchyma of immunocompromised young-adult rats, specifically chosen to avoid the rejection of human cell xenografts and to allow sufficient time in vivo to characterize long-term cell transplants. Graft assessment using immunohistochemistry and cell counts showed that cell density (Fig. 1o) and cell numbers (Fig. 1p) decreased significantly by 2-fold and 2.5-fold, respectively, at 7.5 months post-transplantation compared with 1 month (cell density at 1 month, 9692±744.7 cells/mm3 and at 7.5 months, 4912±4912 cells/mm3, P=0.0043; total cell numbers at 1 month, 207 721±32 780 cells and at 7.5 months, 83 463±33 029 cells, P=0.0472). This lower cell density suggests decreased cell survival but also is consistent with cell migration away from the transplant site. All animals showed surviving transplants in the gray as well as the white matter of the targeted area and grafted cells could be observed in close proximity to choline acetyl transferase-positive motor neurons at both time points (Fig. 1e and j). There were only low levels of Ki67-positive proliferating cells observed at 1 and 7.5 months post-transplantation, and while there was no significant difference between time points (at 1 month, 4.6±1.5% and at 7.5 months, 1.2±0.7%, P=0.1) proliferation appeared to reduce over time (Fig. 1c, d, and q). Consequent to the low levels of Ki67 expression and cell proliferation, no long-term hNPC transplant ever showed signs of cell overgrowth, which attests to the safety of these cells.

At 1 month after grafting, the majority of cells expressed nestin or a combination of nestin and GFAP (nestin: at 1 month, 36.9±5.9% and at 7.5 months, 21.2±4.3%, P=0.1; nestin/GFAP: at 1 month, 54.8±3.3% and at 7.5 months, 48.1±9.9%, P=0.55) (Fig. 1f, g, r, and s), and GFAP-positive cells were observed within the core of the graft. At 7.5 months after grafting, cells migrated away from the transplant site and there was a significant increase in GFAP-positive cells (at 1 month, 8.2±3.3% and at 7.5 months, 30.7±6.9%) (Fig. 1k, l, and t). Increased GFAP expression and morphology of grafted cells in long-term transplants suggest the increased differentiation of grafted cells into mature astrocytes. Importantly, grafted cells showed long-term GDNF expression and, in some instances, large spinal cord motor neurons stained for GDNF suggesting that the host cells were taking up the GDNF released by the hNPCGDNF transplants (Fig. 1h and m).

Discussion

We have previously shown that the injured environment in animal models of disease may provide a milieu that is more conducive to the survival of transplanted hNPCs compared with the intact environment in healthy controls 17,18. However, animal models of disease may not work for long-term transplant assessment, as overt damage and disease progression can lead to animal death before the ideal time point for assessment of cell fate, function, and safety. Instead, young-adult healthy animals or immunodeficient animals (for xenografting without daily immunosuppression) can be used to extend the investigation of central nervous system (CNS) transplants to longer time periods. Here, we report the long-term survival of hNPCs in the spinal cord of athymic nude rats. Increased GFAP expression by the grafted cells indicates in vivo astrocyte differentiation. Importantly, even after long time periods, there was no significant increase in the proliferation of grafted cells and no overt signs of cell overgrowth.

There is a strong non-autonomous feature of motor neuron cell death in ALS where the glial cells surrounding motor neurons are dysfunctional leading subsequently to accelerated motor neuron death 19–21. It has also been shown that the transplantation of astrocytes into murine models of ALS can ameliorate motor neuron cell death and improve function 22. Furthermore, many transplantation-based therapeutic strategies in models of motor neuron disease or acute injury have attributed increased motor neuron survival and functional benefits to the production trophic factors by transplanted cells 23,24. Finally, GDNF is a potent trophic factor for motor neurons 25,26 and when secreted from astrocytes has been shown to be neuroprotective in an acute model of motor neuron injury 27. We have previously shown that hNPCs can be genetically engineered to express GDNF, that transplanted hNPCsGDNF can mature into astrocytes and stably secrete GDNF in various rodent models of CNS injury 18,28 as well as in aged primates, and that hNPCsGDNF 6 transplanted into the SOD1G93A rat spinal cord can enhance motor neuron survival 10,14,15. Here we augment the previous findings by showing that these same cells can survive and stably secrete GDNF for up to 7.5 months without forming tumors.

The safety of hNPCs combined with their differentiation into mature astrocytes and sustained neurotrophic factor delivery makes these cells a promising choice in cell-based therapeutic approaches for ALS and other CNS diseases where functional astrocytes and growth factor secretion may be of benefit.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Soshana Svendsen for critical review and editing of this report. This study was in part supported by funding from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM RP1-05741).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chio A, Logroscino G, Traynor BJ, Collins J, Simeone JC, Goldstein LA, et al. Global epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review of the published literature.Neuroepidemiology 2013;41:118–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinman L, Cudkowicz M.Emerging targets and treatments in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Lancet Neurol 2011;10:481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas MR, Johnson JA.Astrogliosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: role and therapeutic potential of astrocytes.Neurotherapeutics 2010;7:471–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasiene J, Yamanaka K.Glial cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Neurol Res Int 2011;2011:718987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilieva H, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW.Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond.J Cell Biol 2009;187:761–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emborg ME, Ebert AD, Moirano J, Peng S, Suzuki M, Capowski E, et al. GDNF-secreting human neural progenitor cells increase tyrosine hydroxylase and VMAT2 expression in MPTP-treated cynomolgus monkeys.Cell Transplant 2008;17:383–395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley J, Federici T, Park J, Suzuki M, Franz CK, Tork C, et al. Cervical spinal cord therapeutics delivery: preclinical safety validation of a stabilized microinjection platform.Neurosurgery 2009;65:754–761discussion 761–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrstock S, Ebert A, McHugh J, Vosberg S, Moore J, Schneider B, et al. Human neural progenitors deliver glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor to parkinsonian rodents and aged primates.Gene Ther 2006;13:379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capowski EE, Schneider BL, Ebert AD, Seehus CR, Szulc J, Zufferey R, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated genetic modification of human neural progenitor cells for ex vivo gene therapy.J Neurosci Methods 2007;163:338–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols NL, Gowing G, Satriotomo I, Nashold LJ, Dale EA, Suzuki M, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and stem cell implants preserve breathing capacity in a rodent model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andres RH, Horie N, Slikker W, Keren-Gill H, Zhan K, Sun G, et al. Human neural stem cells enhance structural plasticity and axonal transport in the ischaemic brain.Brain 2011;134:1777–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Girman S, Lu B, Bischoff N, Holmes T, Shearer R, et al. Long-term vision rescue by human neural progenitors in a rat model of photoreceptor degeneration.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:3201–3206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostenfeld T, Tai YT, Martin P, Deglon N, Aebischer P, Svendsen CN.Neurospheres modified to produce glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor increase the survival of transplanted dopamine neurons.J Neurosci Res 2002;69:955–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein SM, Behrstock S, McHugh J, Hoffmann K, Wallace K, Suzuki M, et al. GDNF delivery using human neural progenitor cells in a rat model of ALS.Hum Gene Ther 2005;16:509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki M, McHugh J, Tork C, Shelley B, Klein SM, Aebischer P, et al. GDNF secreting human neural progenitor cells protect dying motor neurons, but not their projection to muscle, in a rat model of familial ALS.PloS One 2007;2:e689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svendsen CN, Ter Borg MG, Armstrong RJ, Rosser AE, Chandran S, Ostenfeld T, et al. A new method for the rapid and long term growth of human neural precursor cells.J Neurosci Methods 1998;85:141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostenfeld T, Caldwell MA, Prowse KR, Linskens MH, Jauniaux E, Svendsen CN.Human neural precursor cells express low levels of telomerase in vitro and show diminishing cell proliferation with extensive axonal outgrowth following transplantation.Exp Neurol 2000;164:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behrstock S, Ebert AD, Klein S, Schmitt M, Moore JM, Svendsen CN.Lesion-induced increase in survival and migration of human neural progenitor cells releasing GDNF.Cell Transplant 2008;17:753–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement AM, Nguyen MD, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, Boillee S, Rule M, et al. Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice.Science 2003;302:113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanaka K, Chun SJ, Boillee S, Fujimori-Tonou N, Yamashita H, Gutmann DH, et al. Astrocytes as determinants of disease progression in inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Nat Neurosci 2008;11:251–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki M, Svendsen CN.Combining growth factor and stem cell therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Trends Neurosci 2008;31:192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepore AC, Rauck B, Dejea C, Pardo AC, Rao MS, Rothstein JD, et al. Focal transplantation-based astrocyte replacement is neuroprotective in a model of motor neuron disease.Nat Neurosci 2008;11:1294–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gowing G, Svendsen CN.Stem cell transplantation for motor neuron disease: current approaches and future perspectives.Neurotherapeutics 2011;8:591–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor DM, Boulis NM.Cellular and molecular approaches to motor neuron therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular atrophy.Neurosci Lett 2012;527:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson CE, Phillips HS, Pollock RA, Davies AM, Lemeulle C, Armanini M, et al. GDNF: a potent survival factor for motoneurons present in peripheral nerve and muscle.Science 1994;266:1062–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohn MC.Motoneurons crave glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor.Exp Neurol 2004;190:263–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsadanian A, Pan Y, Li W, Myckatyn TM, Brakefield D.Astrocyte-derived transgene GDNF promotes complete and long-term survival of adult facial motoneurons following avulsion and differentially regulates the expression of transcription factors of AP-1 and ATF/CREB families.Exp Neurol 2006;200:26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebert AD, Barber AE, Heins BM, Svendsen CN.Ex vivo delivery of GDNF maintains motor function and prevents neuronal loss in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease.Exp Neurol 2010;224:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]