Abstract

Purpose

Herpes keratitis (HK) is the leading cause of cornea-derived and infection-associated blindness in the developed world. Despite the availability of effective antivirals, some patients develop refractory disease, drug-resistant infection, and topical toxicity. A nonpharmaceutical treatment modality may offer a unique advantage in the management of such cases. This study investigated the antiviral effect of nonthermal dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma, a partially ionized gas that can be applied to organic substances to produce various biological effects.

Methods

Human corneal epithelial cells and explanted corneas were infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and exposed to culture medium treated with nonthermal DBD plasma. The extent of infection was measured by plaque assay, quantitative PCR, and Western blot. Corneal toxicity assessment was performed with fluorescein staining, histologic examination, and 8-OHdG detection.

Results

Application of DBD plasma–treated medium to human corneal epithelial cells and explanted corneas produced a dose-dependent reduction of the cytopathic effect, viral genome replication, and the overall production of infectious viral progeny. Toxicity studies showed lack of detrimental effects in explanted human corneas.

Conclusions

Nonthermal DBD plasma substantially suppresses corneal HSV-1 infection in vitro and ex vivo without causing pronounced toxicity.

Translational Relevance

Nonthermal plasma is a versatile tool that holds great biomedical potential for ophthalmology, where it is being investigated for wound healing and sterilization and is already in use for ocular microsurgery. The anti-HSV-1 activity of DBD plasma demonstrated here could be directly translated to the clinic for use against drug-resistant herpes keratitis.

Keywords: herpes simplex keratitis, nonthermal plasma, dielectric barrier discharge, corneal epithelium, explant cornea model

Introduction

Herpes keratitis (HK) is the most common cause of cornea-derived blindness and infection-associated blindness in the developed world. While acyclovir and its derivatives have been very successful in HK patients, this condition still presents a clinical problem, with an annual incidence of roughly 11.8 per 100,000 people and a total prevalence of over 500,000 in the United States alone.1–3 In addition, acyclovir-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus (HSV) are beginning to emerge, further emphasizing the need for new antiviral lines of defense in combating HK.4–10 Almost all of the current antiviral drugs target the same viral enzyme (HSV-1 DNA polymerase), which severely limits options for combination therapy and allows for the development of drug resistance. For these reasons, investigations into novel nonpharmacologic methods of suppressing HSV-1 infection in the cornea may be of therapeutic interest.

In this study, we have examined the antiviral properties of liquids treated with nonthermal dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma. “Plasma” is a term used to refer to a partially ionized gas. Plasmas are normally generated in nature or in the laboratory by subjecting a gas to high voltage, which strips electrons from atoms to create ions.11 Man-made plasmas can be generally categorized into thermal and nonthermal. In thermal plasmas, the energized electrons are in equilibrium with the heavy particles, leading to energy transfer and rapid heating of the gas. Nonthermal plasmas, on the other hand, do not facilitate such equilibrium, which leaves the gas at ambient temperature.12 Due to this feature, nonthermal plasmas have recently attracted considerable attention in the biomedical field. Dielectric barrier discharge plasma is a type of nonthermal plasma that was originally introduced by Werner von Siemens in 1857.13,14 The medical applications of DBD plasma have been studied in the context of wound healing, blood coagulation, cancer therapy, surface sterilization, and many more.15–20 Specifically in the cornea, DBD plasma has been explored for its antibacterial,21–23 antifungal,22 and wound healing24–26 properties. Interestingly, however, the antiviral potential of DBD plasma remains largely unexplored.27 Slipenicaia et al.28 were the first to test the effects of DBD plasma on viral infection. Using an ion-flow plasma device, they achieved enhanced resolution of HK in guinea pigs as well as in 25 of 32 treated human patients. In another study, however, Brun et al.22 treated HSV-1 viral particles in suspension with helium-flow plasma prior to infection of Vero cells and reported no significant diminution of the cytopathic effect.

In light of the few and contradictory reports, we set out to characterize the antiviral effects of DBD plasma specifically in the context of HSV-1 keratitis. We had previously described a system for “separated” DBD plasma treatment, in which an aqueous solution, such as cell culture medium, is first exposed to DBD plasma and then applied to cells.29 This is in contrast to the “direct” treatment, where DBD plasma is generated directly on the surface of cultured cells. In our experiments, plasma-treated growth medium was applied to cultured monolayers of human corneal epithelial cells and to intact ex vivo human corneas. This method offers several advantages as compared to the direct DBD plasma treatment of the cornea or the use of flow plasma, another common system for producing plasma. Generation of DBD plasma directly on the tissue strictly depends on the exposed surface being regular and parallel to the electrode. Since human corneas range in curvature and size and are known to have surface irregularities, direct exposure to the electrode would produce damaging arcs30 (localized and concentrated plasma streamers) instead of a uniform discharge. In addition, plasmas generate ozone and contain a minor ultraviolet (UV) component,31 both of which could be damaging to the cornea in the case of a direct treatment. Finally, the use of DBD plasma–treated liquids allows for a greater degree of consistency than either direct DBD plasma or flow plasma treatment, since treated liquids can be generated in a standardized and well-controlled manner and administered as eye drops consistent with standard clinical practice.

In this report, we demonstrate the antiviral potential of DBD plasma–treated liquids in the context of HK. Application of plasma-activated growth medium to HSV-1-infected corneal epithelial cells and ex vivo human corneas caused a significant suppression of infection. Importantly, the antiviral effect was produced in the absence of pronounced corneal toxicity or damage. We propose that the use of DBD plasma–treated liquids, which act through a mechanism different from that of the available antivirals, could be a useful addition to the current HK drug armamentarium. Further studies of the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenotype will allow for optimized use of DBD plasma in herpetic corneal disease.

Methods

Cells and Viruses

All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2, and supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Human corneal epithelial cells immortalized with hTERT (hTCEpi32; a kind gift from James Jester at University of California-Irvine) were grown in complete keratinocyte growth medium 2 (KGM-2; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (CV-133; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). KOS strain34 of HSV-1 (a kind gift from Stephen Jennings at Drexel University College of Medicine) was used throughout, except for the plaque expansion experiment, which was performed with KOS-GFP strain35 (a kind gift from Nigel Fraser at University of Pennsylvania). All viral stocks were titered on CV-1 monolayers.

Cell Culture Model

Subconfluent monolayers of hTCEpi cells were grown in six-well plates. Infections with KOS strain of HSV-1 were carried out at multiplicity of infection (MOI) 0.1 in a 200-μL inoculum volume at 37°C for 1 hour with intermittent rocking. The infected monolayers were then exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium (as described below) and overlaid with fresh KGM-2 for the remainder of experiment. At 16 hours postinfection, phase-contrast images were taken; cells were collected for isolation of DNA, RNA, or protein; and culture medium was collected for plaque assays.

For plaque expansion experiments, hTCEpi monolayers were infected with KOS-GFP strain of HSV-1, which constitutively expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) from a cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. Infections were carried out at very low MOI to ensure that the viral plaques would be sufficiently sparse. Following exposure to DBD plasma–treated medium, cells were overlaid with fresh KGM-2 containing 1.25% wt/vol methocellulose. Infectious plaques were then allowed to develop and were imaged by fluorescence microscopy.

Corneal Explant Model

Human corneas were obtained from the Lions Eye Bank of Delaware Valley. Experimentation using human corneas was approved by the Drexel University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocol established by Alekseev et al.36 for ex vivo corneal culture, infection, and treatment was followed closely. Briefly, corneoscleral buttons were rinsed in PBS containing 200 U/mL penicillin and 200 μg/mL streptomycin. The endothelial concavity was filled with culture medium containing 1% low melting temperature agarose. The corneas were cultured epithelial side up in KGM-2 medium supplemented with 200 U/mL penicillin and 200 μg/mL streptomycin. The next day, they were infected with 1 × 104 plaque forming units (PFU)/cornea of strain KOS HSV-1 for 1 hour, exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium (as described below), and cultured for 24 hours. The epithelial cell layer was collected by scraping to isolate DNA for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, and the culture medium was collected for viral titer quantification by plaque assay.

Generation of DBD Plasma in Atmospheric Air

To initiate uniform DBD in atmospheric air, we used a nanosecond-pulsed power system. The power supply (FID GmbH, Burbach, Germany) generates pulses with +15.5-kV pulse amplitude in a 50 Ω coaxial cable (31 kV on the high-voltage electrode due to pulse reflection), 10-ns pulse duration (90% amplitude), 2-ns rise time, and 3-ns fall time. Power measurements were performed using a high-voltage probe (P6015A, 75-MHz bandwidth; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR) and Pearson current monitor (model 6585, usable time 1 ns, 1 GHz bandwidth; Palo Alto, CA) connected to a 1-GHz oscilloscope (DPO4104B; Tektronix). Because the probe's frequency response limits its ability to accurately detect the pulse shape, voltage was measured using back current shunts (BCS). For this purpose, pulses were delivered to the electrodes via 30 m of RG 393/U high-voltage coaxial cable, and BCS was mounted 6.7 m from the output of the power supply. The shunt comprised 10 carbon-composition 3 Ω resistors (OF30GJE-ND; DigiKey, Thief River Falls, MN) soldered into a gap within the shield of the cable.37 Amplitude calibration of the BSC was performed using a high-voltage probe. In order to account for the displacement current, which was later subtracted from the total current of the discharge, measurements were first done with a large electrode gap when the electric field in the gap was not sufficient to generate a discharge and therefore only displacement current could be measured. These measurements were also confirmed by a well-established technique for estimation of energy deposition based on comparison of the first incident and reflected voltage pulses in a long cable.38 These measurements estimate the resulting DBD pulse energy at 45 ± 4 mJ. Liquid treatment experiments were performed at a frequency of 1 kHz, corresponding to the total plasma discharge power of 1.88 ± 0.2 W/cm2.

Dielectric barrier discharge optical emission spectrum was obtained using a fiber optic bundle (10 fibers, 200-μm core) connected to a spectrometer system (TriVista TR555) with a digital intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) camera (PI-MAX), all purchased from Princeton Instruments (Trenton, NJ). The rotational temperature of nitrogen, which represents the gas temperature,39 was determined by fitting a synthetic spectrum to the experimental spectrum of the (0–2) transition emission bands of the N2(C 3Πu-B 3Πg) transition (second positive system) in the range 360 to 381 nm, using the Specair 3.0 program (SpectralFit S.A.S., Antony, France). The measured rotational temperature of nitrogen was 343 ± 6 K.

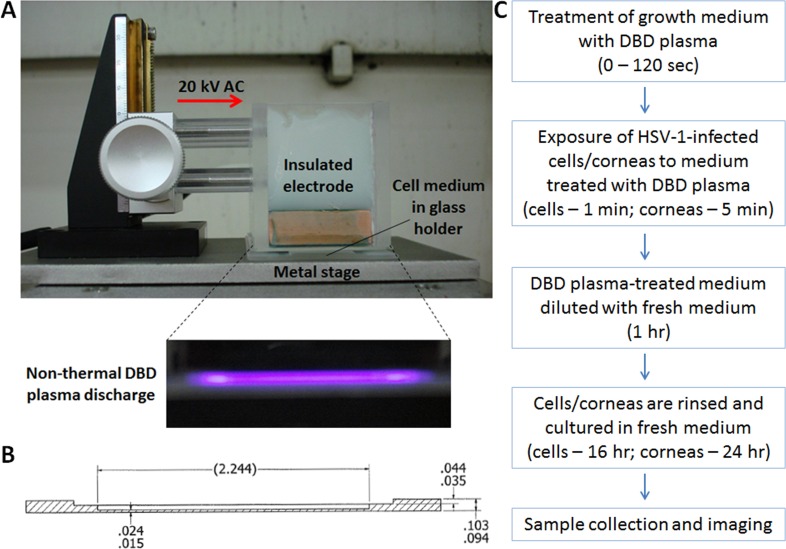

Nonthermal DBD Plasma Treatment of Culture Medium

Dielectric barrier discharge plasma–treated liquid was generated by exposing 1 mL complete KGM-2 medium in a glass holder (Fig. 1B) to DBD plasma, as shown in the photograph (Fig. 1A). The potency of plasma-treated liquid was adjusted by varying the duration of treatment time (0–180 seconds). Once treated, the liquid was applied to cells or corneas (400 μL for cells, 800 μL for corneas) in six-well plates at exactly 1 hour after the start of HSV-1 infection. Cells were incubated with the DBD plasma–treated medium for 1 minute and corneas for 5 minutes before fresh KGM-2 (2 mL for cells, 6 mL for corneas) was added to each well to dilute the DBD plasma–treated medium. After 1 hour, cells or corneas were rinsed and overlaid with fresh KGM-2 for the remainder of the experiment (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. .

Preparation and use of DBD plasma–treated liquids. (A) Setup for generation of nonthermal DBD plasma. Fully insulated electrode receives 15- to 20-kV current alternating at 1.0-kHz frequency. One milliliter liquid is placed into a custom-made glass holder (measurements are shown in inches) (B), such that there is a 1-mm gap between the insulated electrode and the liquid surface. The alternating current ionizes air molecules in the 1-mm gap, producing a characteristic purple glow (inset in [A]). (C) Schematic outline of a typical experiment. The medium is treated by DBD plasma for varying amounts of time (0–120 seconds), depending on the desired potency of treatment. DBD plasma–treated medium is removed from the glass holder and applied to cultured cells or corneas as described in the Methods section.

Corneal Toxicity Assessment

Explanted human corneas not infected with HSV-1 were exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium in the same manner as described above and were subsequently cultured for 24 hours. For histology studies, corneas were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde/2% sucrose solution, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For assessment of epithelial toxicity, corneas were briefly stained with fluorescein (1% wt/vol in PBS), and epithelial defects were imaged with 464-nm-wavelength blue light (LDP LLC, Carlstadt, NJ).

Genotoxic Toxicity Assessment

Explanted human corneas were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (200 μM), UV light (20 J/m2), DBD plasma–treated KGM-2 (120 seconds), or mock treatment. The corneas were then incubated in fresh KGM-2 for 2 hours and flash-frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. Frozen tissue blocks were sectioned at 5-μm thickness, fixed, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence. Detection of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers with the TDM-2 primary antibody (a kind gift from Toshio Mori at Nara Medical University, Japan) was performed according to a previously published protocol.29 Oxidative damage to nucleic acids was assessed by staining with the 8-OHdG primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), which detects 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, 8-hydroxyguanine, and 8-hydroxyguanosine. Standard immunofluorescence protocol was followed. Nuclei were counterstained with Höchst 33,258.

Viral Genome Replication and Transcription

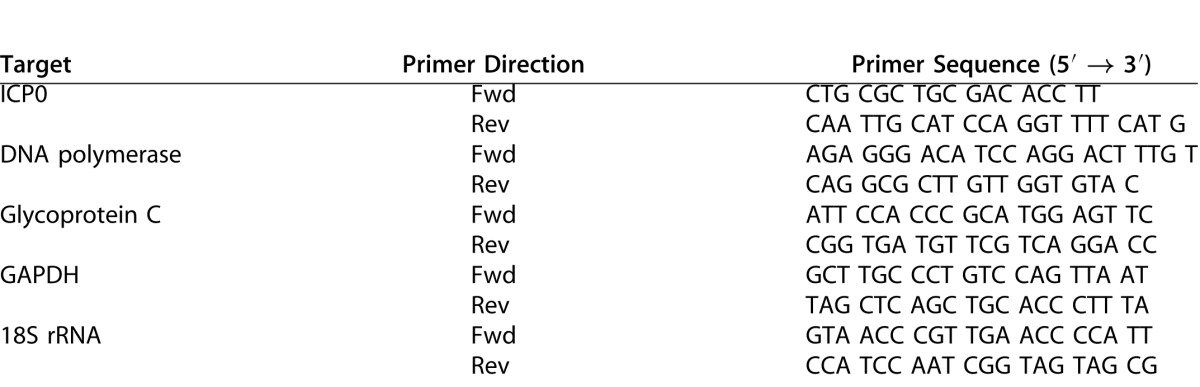

Viral genome replication and transcription were measured by qPCR. Total DNA and RNA from infected cells were isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit and the RNeasy Mini Kit, respectively (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was converted to cDNA using qScript (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Real-time qPCR was performed with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Target primers for UL30 (DNA polymerase catalytic subunit) and reference primers for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used to measure genome replication. Transcription of the three gene families was measured with primers for RL2 (ICP0), UL30 (DNA polymerase catalytic subunit), and UL44 (gC), with reference primers for the 18S rRNA (Table). All primer sequences have been previously published.40

Table 1. .

PCR Primers Used in This Study

Western Blot

Standard protocol was followed for Western blot analysis. Cell lysates were collected in 200 μL Laemmli buffer, vortexed, and boiled at 95°C for 5 minutes. Protein concentrations were measured by bicinchoninic acid assay. SDS–PAGE was followed by transfer onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, which was then blocked in 5% BSA. Blots were stained with primary antibodies against glycoprotein C (rabbit polyclonal; a kind gift from Roselyn Eisenberg at University of Pennsylvania) and nucleolin (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were stained with secondary antibodies and visualized with the Odyssey near-infrared system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test and is indicated by ns (P > 0.05), * (P < 0.05), ** (P < 0.01), or *** (P < 0.001).

Results

DBD Plasma–Treated Medium Suppresses HSV-1 Infection in Human Corneal Epithelial Cells

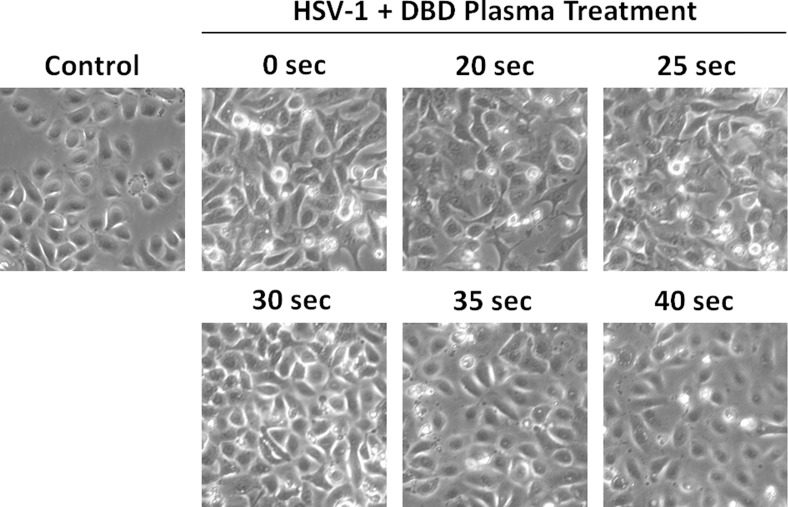

In order to obtain a general characterization of the effect of DBD plasma on HSV-1 infection, we conducted experiments using hTCEpi corneal epithelial cells. Monolayers of hTCEpi cells were infected with HSV-1 at low MOI (0.1) to simulate physiologically relevant viral titers. KGM-2 growth medium was treated with DBD plasma for 0 to 40 seconds and then applied to the infected cells as described in Methods (Fig. 1). This range of treatment times was chosen based on our previous studies of biological effects of DBD plasma (data not shown). The cytopathic effect produced by HSV-1 infection was suppressed by DBD plasma–treated medium in a dose-dependent manner, with the maximal antiviral activity achieved at 35 to 40 seconds of DBD plasma treatment (Fig. 2). To gain better understanding of this antiviral effect, we sought to monitor the spread of HSV-1 infection within the hTCEpi monolayers. To this end, we infected confluent hTCEpi cells with KOS-GFP strain of virus, which constitutively expresses GFP allowing for easy visual detection of infected cells. The monolayers were overlaid with methocellulose-containing medium, limiting viral infection to direct spread. Examination of the infectious plaques by fluorescence microscopy revealed that DBD plasma greatly limited HSV-1 plaque expansion (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. .

DBD plasma-treated medium suppresses the cytopathic effect of HSV-1 in human corneal epithelial cells. hTCEpi cells were infected at MOI 0.1 and exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 0 to 40 seconds. Control cells were neither infected nor treated. Phase-contrast images were taken at 16 hours postinfection. Microphotographs are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Figure 3. .

DBD plasma–treated medium limits the expansion of HSV-1 plaques in human corneal epithelial cell monolayers. hTCEpi monolayers were infected with KOS-GFP strain of HSV-1 at a low MOI, exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 0 to 40 seconds, and overlaid with methocellulose-containing medium to allow for plaque development. Plaques were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. A representative plaque from each treatment group is shown. Bar: 400 μm. n = 2.

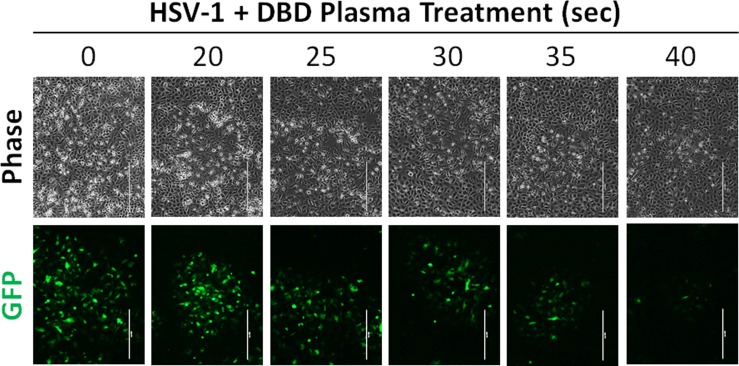

To provide a quantitative evaluation of the antiviral effect of DBD plasma, we used a qPCR assay for the measurement of viral genome replication. hTCEpi monolayers that had been exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium contained significantly lower HSV-1 genome copies than control monolayers. The inhibition of genome replication was greater than 90% at the 40-second treatment intensity (Fig. 4A). Culture media from the same monolayers were analyzed by plaque assay, revealing a concomitant inhibition of infectious viral particle production, which reached 150-fold reduction at the 40-second treatment intensity (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the initial assessment of the cytopathic effect (Fig. 2), the maximal effect on both the genome replication and the viral titers was achieved at the 35- to 40-second treatment intensity.

Figure 4. .

DBD plasma–treated medium reduces viral replication in human corneal epithelial cells. hTCEpi cells were infected at MOI 0.1 and exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 0 to 40 seconds. (A) Total DNA was collected at 16 hours postinfection for analysis by qPCR with primers against HSV-1 polymerase and GAPDH. Bars represent relative ΔΔC(t) values ± SEM. (B) Supernatants were collected at 16 hours postinfection for analysis by plaque assay. A representative experiment is shown. n = 3 for all.

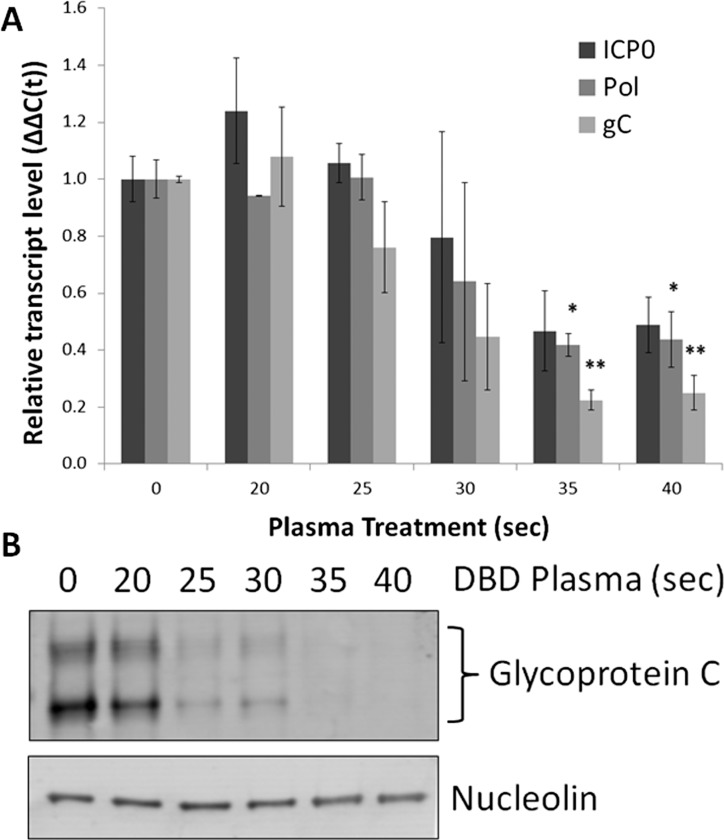

The inhibition of genome replication caused a subsequent reduction in the accumulation of viral gene products. Levels of viral transcripts from all three kinetic families—immediate early, early, and late—were reduced, as measured by qRT-PCR with primers against RL2 (ICP0), UL30 (DNA polymerase catalytic subunit), and UL44 (glycoprotein C) (Fig. 5A). There was a consistent reduction in the accumulation of glycoprotein C protein product as detected by Western blot (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the decrease of glycoprotein C protein levels was more pronounced than the decrease of its mRNA transcript, which could point to an unexplored translational effect of DBD plasma.

Figure 5. .

DBD plasma–treated medium reduces accumulation of HSV-1 transcripts and protein in human corneal epithelial cells. hTCEpi cells were infected at MOI 0.1 and exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 0 to 40 seconds. Cells were collected for protein lysates or RNA isolation at 16 hours postinfection. (A) Transcripts from all three HSV-1 gene families were detected with primers for ICP0 (immediate early), DNA polymerase (early), and glycoprotein C (true late). Bars represent relative ΔΔC(t) values ± SEM. (B) Glycoprotein C accumulation was assayed by Western blot. Nucleolin is a loading control. n = 2 for all.

Taken together, our experiments in the corneal tissue culture model reveal a potent antiviral effect of DBD plasma. The 35- to 40-second treatment intensity resulted in pronounced reduction of the cytopathic effect, infectious plaque expansion, viral genome replication, production of infectious progeny, and accumulation of viral gene products.

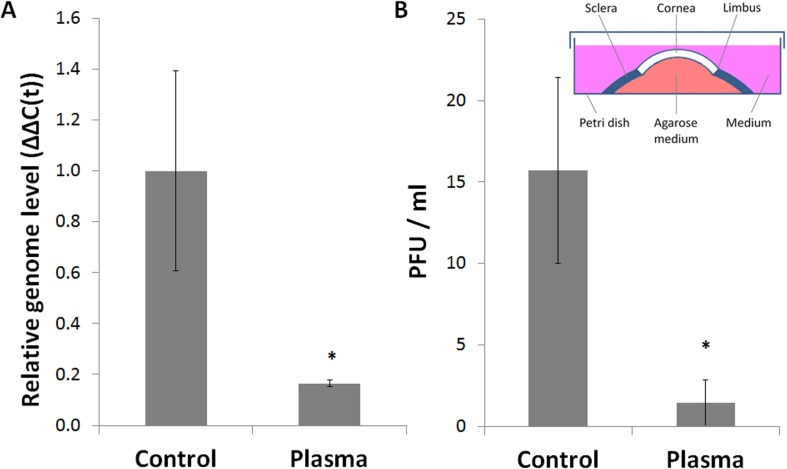

DBD Plasma–Treated Medium Suppresses HSV-1 Infection in Explanted Human Corneas

In order to extend our experiments to a more physiologically relevant model of corneal HSV-1 infection, we followed the method of Alekseev et al.36 for ex vivo corneal culture, infection, and treatment (inset in Fig. 6B). Intact human corneoscleral buttons were infected with HSV-1 and exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium similarly to the in vitro experiments. Due to the inherent differences between cell monolayers and explanted corneas, a new dose–response curve was generated (data not shown); based on the ex vivo dose response, 120 seconds was chosen as the optimal treatment intensity to be used in subsequent experiments. A set of 16 donor-matched human corneas was infected and exposed to medium treated with DBD plasma or mock (DBD plasma power source turned off). We achieved a substantial (over 80%) reduction in HSV-1 genome replication in treated corneas compared to matched mock-treated controls (Fig. 6A). This decrease was accompanied by a similar reduction of the viral load in the culture medium (Fig. 6B). Thus, our initial in vitro findings (Fig. 4) are supported by our ex vivo experiments in intact human corneas.

Figure 6. .

DBD plasma–treated medium suppresses HSV-1 replication in explanted human corneas. Human corneas were maintained in ex vivo culture as shown in the schematic (inset in [B]). Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Visualized Experiments.36 Corneas were infected with 1 × 104 PFU/cornea and exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 120 seconds. (A) Total DNA was isolated from the epithelial layers at 24 hours postinfection and analyzed by qPCR with primers against HSV-1 DNA polymerase and GAPDH. Bars represent relative ΔΔC(t) values ± SEM. (B) Culture media were collected from the same corneas and processed by plaque assay. Bars represent average viral titers ± SEM. Data were collected from 16 matched corneas obtained from 8 donors (n = 8).

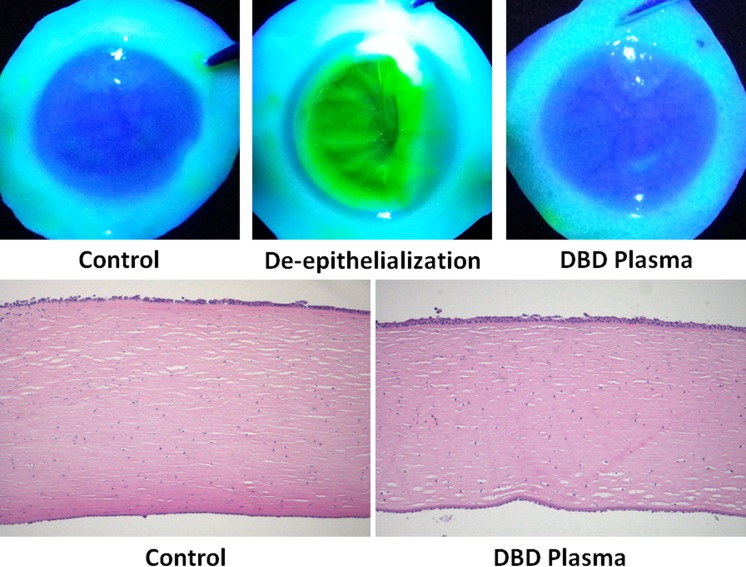

DBD Plasma–Treated Medium Exhibits Low Toxicity in Explanted Human Corneas

Brun et al.22 have performed comprehensive and extensive toxicity studies, demonstrating a lack of pronounced or lasting detrimental effects of nonthermal plasma to the human cornea. However, since the method of plasma treatment utilized in the present study is different from the helium-flow plasma used by Brun et al., additional toxicity assessment was necessary. Explanted human corneas were exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium (120 seconds) and subsequently cultured under conditions identical to those in virus-inhibition experiments (Fig. 6). At 24 hours posttreatment, the integrity of corneal epithelium was assessed by fluorescein staining, which revealed no observable abnormalities (Fig. 7A). In addition, a set of 12 donor-matched corneas was exposed to mock-treated or DBD plasma–treated medium and examined for histologic changes in the corneal structure. In agreement with the fluorescein staining, no consistent abnormalities were visually detectible in the H&E-stained tissue sections (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. .

DBD plasma–treated medium exhibits low toxicity in explanted human corneas. Ex vivo human corneas were exposed to KGM-2 medium treated with DBD plasma for 120 seconds and incubated for 24 hours. (A) Epithelial toxicity was assessed by fluorescein staining, with surgically de-epithelialized corneas serving as a positive staining control. n = 2. (B) Histologic assessment of toxicity was performed by examining H&E-stained tissue sections from 12 matched corneas obtained from 6 donors. Representative images from a matched pair are shown (n = 6).

Plasmas have been shown to produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species,11,12 as well as a minor amount of UV energy.31 These entities are known to be damaging to cells and can be particularly deleterious to the nucleic acids (especially DNA) by catalyzing mutagenic structural changes. In particular, UV exposure promotes the formation of aberrant structures known as cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs),41,42 and oxidation of nucleic acids can promote inappropriate nucleotide substitutions in the genome.43 For this reason, we examined the potential toxic effects of DBD plasma–treated medium on the nucleic acids of corneal epithelial cells. Explanted human corneas were exposed to DBD plasma–treated medium, mock-treated medium, or damaging agents for positive control (UV and H2O2). Not surprisingly, DBD plasma–treated medium did not induce the formation of CPDs, as detected by staining with an antibody specific to these structures (Fig. 8A). Importantly, the same DBD plasma treatment intensity that produces viral inhibition (120 seconds) did not induce appreciable levels of nucleic acid oxidation within the epithelium, as detected by staining with an antibody specific to 8-OHdG, a common marker of oxidative damage44 (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. .

DBD plasma–treated medium does not produce cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers or nucleic acid oxidation in explanted human corneas. Ex vivo human corneas were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (200 μM), UV light (20 J/m2), DBD plasma–treated KGM-2 (120 seconds), or mock treatment. The corneas were then incubated in fresh KGM-2 for 2 hours, flash-frozen in OCT compound, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence. (A) Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) were detected with the TDM-2 antibody, and (B) oxidized nucleic acids were detected with the 8-OHdG antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with Höchst 33,258. Fluorescent images are overlaid with phase-contrast images in the merge. Bar: 100 μm. Representative data are shown. n = 2.

Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that DBD plasma–treated medium suppresses HSV-1 infection in explanted human corneas without producing appreciable toxicity, as monitored by fluorescein staining, histologic assessment, and detection of genotoxic damage.

Discussion

The use of nonthermal plasmas in biomedical applications holds significant promise and has generated much interest in recent years.15 In the field of ophthalmic research, nonthermal plasmas have been investigated for potential use in wound healing24–26 and bacterial and fungal sterilization,21–23 and are already in use for ocular surgery (yttrium aluminium garnet laser45,46 and Fugo plasma blade47). The work presented here contributes to these investigations by demonstrating the antiviral potential of DBD plasma in the treatment of HSV-1 corneal infection. The advantage of plasma technology is its high degree of versatility and adaptability. Nonthermal plasmas can be generated at a wide range of energy settings, in various customized gaseous media, and using a growing variety of electrodes. This multitude of parameters involved in plasma generation allows for fine-tuning of the nature, quality, and intensity of the produced plasma in order to fit a specific biomedical need.11,15 Dielectric barrier discharge plasma electrodes can be manufactured in different shapes and sizes, and the use of microelectrodes48,49 holds great potential for novel methods of targeted intervention within precise anatomical locations on the ocular surface as well as in the internal structures of the eye.

The mechanisms underlying the biological activities of nonthermal plasmas remain to be described and are likely multifactorial and highly dependent on plasma type and delivery method. The chemical species generated using our DBD plasma source are currently under investigation, but our prior studies29 point to the possible reactive oxygen species–mediated production of stable amino acid hydroperoxides in the treated medium. However, the DBD plasma source used in those investigations operates at substantially different frequencies from the one employed in the present work, making such extrapolations speculative. Our preliminary measurements performed using Fourier transform infrared absorption spectroscopy (D. Dobrynin, unpublished data, 2013) show that DBD plasma in atmospheric gas phase generates ozone (1.7 × 1017 cm−3), H2O2 (4.2 × 1017 cm−3), and N2O groups (2 × 1015 cm−3), whereas the main component in liquid is H2O2, with generation rate of approximately 4 μM/J. However, it is currently unclear what minor species may be generated from the various organic components present in the treated cell culture medium.

A significant obstacle presented by the current state of the field is the absence of a reliable reference system for the standardization and measurement of plasma. While the electrical power delivered to the insulated electrode can be easily quantified, it does not directly translate to a comparable universal measurement of the energy actually received by the treated tissue. Various biological parameters have been proposed as surrogate markers of treatment intensity (e.g., pH, reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage), but they tend to be inconsistent and limited strictly to their biological meaning. Thus, the development of a convention for the measurement of biological activity of plasmas is necessary for comparison and reproducibility of data across plasma source devices, disease models, and laboratories, and would facilitate the elucidation of the cellular mechanisms affected by plasma.

The use of DBD plasma–treated liquids may provide useful therapeutic advantages for the treatment of corneal herpetic infections. Since this is a nonpharmacologic agent with a mechanism of action unrelated to the inhibition of HSV-1 DNA polymerase, it may serve as a unique option for patients with drug-resistant infection. It could also be used in combination therapy with established antiviral agents. The common target of the majority of current antiherpetic medications allows for the development of multidrug resistance. This is a growing concern in the immunocompromised population,6 where suppression of infection relies entirely on therapeutic intervention. Thus, the addition of DBD plasma to the accepted drug armamentarium in these patients may counteract the development of resistance. In addition, recent interest in the use of plasmas for the enhancement of wound healing,15,16,18 including corneal ulceration,24,25 could point to a possible 2-fold effect of DBD plasma whereby the reduction of viral load is accompanied by expedited resolution of the epithelial ulcer.

An intriguing concept that has not been addressed in this study is that DBD plasma may have analogous antiviral activity against other members of the herpesviridae family, which includes such prominent ocular pathogens as varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus type 2, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus.50

In summary, this work provides seminal evidence for the antiviral effect of DBD plasma–treated medium. Human corneal epithelial cells and explanted corneas treated in this study experienced greatly reduced levels of HSV-1 infection without developing overt toxicity. The results of this study warrant necessary further investigations to characterize the underlying molecular mechanisms, optimize treatment parameters, detail the toxicity profile of DBD plasma, and advance these investigations into in vivo models of herpes keratitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Lions Eye Bank of Delaware Valley for providing human corneas, Peter Laibson and members of the Clifford laboratory for their intellectual input, and Danil Dobrynin at the A.J. Drexel Plasma Institute for helpful discussions and engineering expertise.

Supported by a W.M. Keck Foundation grant to the A.J. Drexel Plasma Institute and a National Research Service Award Training Fellowship (OA) (1F30DK094612-O1A1).

Footnotes

Disclosure: O. Alekseev, National Institutes of Health (F); K. Donovan, None; V. Limonnik, None; J. Azizkhan-Clifford, W.M. Keck Foundation (F)

Oleg Alekseev and Kelly Donovan contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Toma HS, Murina AT, Areaux RG, Jr, et al. Ocular HSV-1 latency, reactivation and recurrent disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23:249–273. doi: 10.1080/08820530802111085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448–462. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RC, Hodge DO, Liesegang TJ, Baratz KH. Incidence, recurrence, and outcomes of herpes simplex virus eye disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2007: the effect of oral antiviral prophylaxis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1178–1183. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrel S, Aime C, Hermet L, Ait-Arkoub Z, Agut H, Boutolleau D. Surveillance of herpes simplex virus resistance to antivirals: a 4-year survey. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussin A. Md Nor NS, Ibrahim N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of induced acyclovir-resistant clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus type 1. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459–472. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00615-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malvy D, Treilhaud M, Bouee S, et al. A retrospective, case-control study of acyclovir resistance in herpes simplex virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:320–326. doi: 10.1086/431585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choong K, Walker NJ, Apel AJ, Whitby M. Aciclovir-resistant herpes keratitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:309–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laibson PR. Resistant herpes simplex keratitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:227–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan R, de Vries RD, Osterhaus AD, Remeijer L, Verjans GM. Acyclovir-resistant corneal HSV-1 isolates from patients with herpetic keratitis. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:659–663. doi: 10.1086/590668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridman A. Plasma Chemistry. New York: Cambridge University Press;; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner HE, Brandenburg R, Kozlov KV, Sonnenfeld A, Michel P, Behnke JF. The barrier discharge: basic properties and applications to surface treatment. Vacuum. 2003;71:417–436. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siemens W. Ueber die elektrostatische Induction und die Verzoegerung des Stroms in Flaschendraehten. Poggendorffs Ann Phys Chem. 1857;102:66–122. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kogelschatz U. Dielectric-barrier discharges: their history, discharge physics, and industrial applications. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2003;23:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fridman A, Friedman G. Plasma Medicine. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons;; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridman G, Friedman G, Gutsol A, Shekhter AB, Vasilets VN, Fridman A. Applied plasma medicine. Plasma Process Polym. 2008;5:503–533. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridman G, Peddinghaus M, Ayan H, et al. Blood coagulation and living tissue sterilization by floating-electrode dielectric barrier discharge in air. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2006;26:425–442. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalghatgi SU, Fridman G, Cooper M, et al. Mechanism of blood coagulation by nonthermal atmospheric pressure dielectric barrier discharge plasma. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 2007;35:1559–1566. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridman G, Brooks AD, Balasubramanian M, et al. Comparison of direct and indirect effects of non-thermal atmospheric-pressure plasma on bacteria. Plasma Process Polym. 2007;4:370–375. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fridman G, Shereshevsky A, Jost MM, et al. Floating electrode dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air promoting apoptotic behavior in melanoma skin cancer cell lines. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2007;27:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkner R. Plasma Seen as an Anti-Infective. Ophthalmology Management. Ambler, PA: Penta Vision;; 2012. pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brun P, Brun P, Vono M, et al. Disinfection of ocular cells and tissues by atmospheric-pressure cold plasma. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e33245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martines E, Brun P, Aragona M, et al. A novel plasma source for sterilization of living tissues. New J Phys. 2009;11:115014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gundarova RA, Chesnokova NB, Shekhter AB, et al. Effects of gaseous flow containing nitric oxide on the eyeball structures (an experimental study) [in Russian] Vestn Oftalmol. 2001;117:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chesnokova NB, Gundorova RA, Kvasha OI, et al. An experimental substantiation of nitric-oxide containing gas flow in the treatment of eye traumas [in Russian] Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2003;5:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alhabshan R, Belyea D, Stepp MA, et al. Effects of in-vivo application of cold atmospheric plasma on corneal wound healing in New Zealand white rabbits. Int J Ophthalmic Pathol. 2013;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann JL, Dumler K, Shimizu T, et al. Effects of cold atmospheric plasmas on adenoviruses in solution. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2011;44:505201. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slipenicaia VD, Lupan DS, Rudenco VM. The treatment of herpetic keratitis by ion-plasma coagulation of the cornea [in Romanian] Oftalmologia. 1993;37:261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalghatgi S, Kelly CM, Cerchar E, et al. Effects of non-thermal plasma on mammalian cells. PloS ONE. 2011;6:e16270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eliasson BKU. Modeling and applications of silent discharge plasmas. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 1991;19:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kogelschatz U, Eliasson B, Egli W. Dielectric-barrier discharges. principle and applications. J Phys IV France. 1997;7:47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson DM, Li L, Fisher S, et al. Characterization of growth and differentiation in a telomerase-immortalized human corneal epithelial cell line. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:470–478. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen FC, Girardi AJ, Gilden RV, Koprowski H. Infection of human and simian tissue cultures with Rous sarcoma virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;52:53–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith KO. Relationship between the envelope and the infectivity of herpes simplex virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1964;115:814–816. doi: 10.3181/00379727-115-29045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lock M, Miller C, Fraser NW. Analysis of protein expression from within the region encoding the 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:3413–3426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3413-3426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alekseev O, Tran AH, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Ex vivo organotypic corneal model of acute epithelial herpes simplex virus type I infection. J Vis Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/3631. e3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seepersad Y, Pekker M, Shneider MN, Fridman A, Dobrynin D. Investigation of positive and negative modes of nanosecond pulsed discharge in water and electrostriction model of initiation. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2013;46 355201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marinov IL, Guaitella O, Rousseau A, Starikovskaia SM. Successive nanosecond discharges in water. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 2011;39:2672–2673. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruggeman P, Brandenburg R. Atmospheric pressure discharge filaments and microplasmas: physics, chemistry and diagnostics. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2013;46 464001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alekseev O, Donovan K, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase suppresses herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;55:706–715. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodsell DS. The molecular perspective: ultraviolet light and pyrimidine dimers. Oncologist. 2001;6:298–299. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-3-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouret S, Baudouin C, Charveron M, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are predominant DNA lesions in whole human skin exposed to UVA radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13765–13770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604213103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dizdaroglu M. Oxidatively induced DNA damage: mechanisms, repair and disease. Cancer Lett. 2012;327:26–47. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis C. 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): a critical biomarker of oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinogen Ecotoxicol Rev. 2009;27:120–139. doi: 10.1080/10590500902885684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fankhauser F, Kwasniewska S. Lasers in Ophthalmology: Basics, Diagnostic and Surgical Aspects: A Review. The Hague, The Netherlands: Kugler Publications;; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinert RF, Puliafito CA, Kittrell C. Plasma shielding by Q-switched and mode-locked Nd-YAG lasers. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)80027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roy H, Singh D, Fugo RJ. Ocular Applications of the Fugo Blade. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staack D, Fridman A, Gutsol A, Gogotsi Y, Friedman G. Nanoscale corona discharge in liquids, enabling nanosecond optical emission spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:8020–8024. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawai Y, Ikegami H, Sato N, et al. Industrial Plasma Technology: Applications from Environmental to Energy Technologies. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH;; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farooq AV, Shah A, Shukla D. The role of herpesviruses in ocular infections. Virus Adaptation and Treatment. 2010;2:115–123. [Google Scholar]