Abstract

Rationale

Early social experiences are of major importance for behavioural development. In particular, social play behaviour during post-weaning development is thought to facilitate the attainment of social, emotional and cognitive capacities. Conversely, social insults during development can cause long-lasting behavioural impairments and increase the vulnerability for psychiatric disorders, such as drug addiction.

Objectives

To investigate whether a lack of social experiences during the juvenile and early adolescent stage, when social play behaviour is highly abundant, alters cocaine self-administration in rats.

Methods

Rats were socially isolated from postnatal day 21 to 42 followed by re-socialization until adulthood. Cocaine self-administration was then assessed under a fixed ratio and progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Next, cue, cocaine and stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking was determined following extinction of self-administration.

Results

Early social isolation resulted in an enhanced acquisition of self-administration of a low dose (0.083 mg/infusion) of cocaine, but the sensitivity to cocaine reinforcement, assessed using a dose-response analysis, was not altered in isolated rats. Moreover, isolated rats displayed an increased motivation for cocaine under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Extinction and reinstatement of cocaine seeking was not affected by early social isolation.

Conclusions

Early social isolation causes a long-lasting increase in the motivation to self-administer cocaine. Thus, aberrations in post-weaning social development, such as the absence of social play, enhance the vulnerability for drug addiction later in life.

Keywords: Social isolation, Adolescence, Cocaine, Self-administration, Motivation, Reinforcement, Extinction, Reinstatement

Introduction

Social experiences early in life are of major importance for behavioural development, since they serve as practice scenarios to become competent, socially mature adults (Pellegrini and Smith 1998; Pellis and Pellis 2009; Špinka et al. 2001). Conversely, disruptions in the early social environment can lead to long-lasting neurobiological changes that profoundly increase the risk for psychiatric disorders in later life, such as drug addiction (Braun and Bock, 2011; Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009; Karelina and DeVries 2011). Interactions between social factors and addictive behaviour have been well-documented in human and animal studies, suggesting that impaired social attachment during early development can enhance the susceptibility to drug addiction (for reviews see Nader et al. 2012; Neisewander et al. 2012; Young et al. 2011).

During post-weaning development (i.e. childhood and adolescence in humans, roughly equivalent to the juvenile and adolescent stages in rodents), marked changes in the structure of social behaviour take place. This is signified by an abundance of social play behaviour, which peaks during the juvenile/early adolescent phase and declines to low levels after sexual maturation (Panksepp 1981). Social play behaviour is the earliest form of social activity directed at peers, and it is thought to subserve neural and behavioural development (Fagen 1981; Graham and Burghardt, 2010; Panksepp et al. 1984; Pellis and Pellis 2009; Špinka et al. 2001; Vanderschuren et al. 1997). Indeed, post-weaning social isolation for a restricted period during which social play is highly abundant has been shown to cause long-lasting impairments in the social, emotional and cognitive domain (Baarendse et al. 2013; Lukkes et al. 2009a; Potegal and Einon 1989; Van den Berg et al. 1999).

In keeping with its importance for development, social play is a highly rewarding activity, as demonstrated by its ability to support place conditioning, maze learning and operant conditioning (Trezza et al. 2011; Vanderschuren 2010). Moreover, social play behaviour is modulated by neural systems that are also involved in the pleasurable and motivational properties of food, sex, and drugs of abuse (Trezza et al. 2010; Siviy and Panksepp 2011), and the rewarding properties of social play behaviour are strongly influenced by drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, nicotine and methylphenidate (Thiel et al. 2008; -2009; Trezza et al., 2009). Therefore, early social experiences may influence the development of the neural circuitry underlying the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. Indeed, social isolation during post-weaning development, depriving the animals of the possibility to engage in a highly pleasurable and developmentally important activity, causes long-lasting changes in the neural substrates of reward and motivation (Fone and Porkess 2008; Heidbreder et al. 2000; Neisewander et al. 2012; Robbins et al. 1996).

Previous studies in rats have shown that housing animals in isolation after weaning enhances drug-directed behaviour, apparent as a higher oral intake of ethanol (Schenk et al. 1990) and morphine (Marks-Kaufman and Lewis 1984). Furthermore, post-weaning social isolation enhances intravenous self-administration of cocaine (Boyle et al. 1991; Ding et al. 2005; Gipson et al. 2011; Howes et al. 2000; Schenk et al. 1987) and amphetamine (Bardo et al. 2001). However, reduced self-administration of intravenous cocaine and intra-accumbens amphetamine, especially at high doses, has also been reported (Howes et al. 2000; Phillips et al. 1994a; Phillips et al. 1994b). Together, these findings indicate that post-weaning social isolation alters the sensitivity to the positive subjective and reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. However, these studies used the so-called isolation rearing model, in which animals are continuously socially isolated from weaning onwards. Therefore, the critical time window for social experiences to influence the later vulnerability for addictive behaviour remains unclarified.

The aim of the present study was to assess the long-term effects of a disrupted social development on intravenous cocaine self-administration. To that aim, we socially isolated rats from postnatal day (PND) 21–42, a time period that is comparable to childhood and early adolescence in humans (McCutcheon and Marinelli 2009; Spear 2000), followed by re-socialization for six weeks. Since we were interested in the importance of social play behaviour for behavioural development, we chose to specifically isolate the animals during the period when social play behaviour is most abundant (Panksepp 1981). Cocaine self-administration was studied under fixed ratio (FR) and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement. Subsequently, we assessed the degree to which a cocaine-associated cue, cocaine itself or the pharmacological stressor yohimbine evoked reinstatement of cocaine-seeking following extinction of self-administration. As summarized above, isolation rearing generally results in increased cocaine self-administration, and social play behaviour is thought to facilitate the development of reward-related neural circuits. We therefore hypothesized that early social isolation enhances cocaine self-administration.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Male Lister Hooded rats (Charles River, Germany) arrived in litters of 6–8 pups at an age of 14 days with a nursing mother. They were housed in climate controlled rooms under a reversed 12hr day/night cycle (lights on: 7 p.m.). At 21 days of age, rats were weaned and housed either socially (SOC) or individually (ISO). The rats of the ISO group were re-socialized, i.e. housed together with another previously isolated animal, on day 43. After several weeks of social housing, intravenous surgery took place when the animals were 12 weeks old. During the course of behavioural testing, rats were singly housed and placed on a restricted diet of 20 g of standard rat chow (SDS, UK) per day. Body weights were monitored on a weekly basis. The rats were fed in their home cages at the end of the experimental day, to avoid association between the self-administration sessions and feeding. Water was available ad libitum, except during self-administration testing. Self-administration sessions were carried out between 9 a.m.–6 p.m., for 5 days a week. The same group of rats was used for all experiments. Experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Utrecht University and were conducted in agreement with Dutch laws (Wet op de Dierproeven, 1996) and European regulations (Guideline 86/609/EEC).

Surgery

Rats were anaesthetised with ketamine hydrochloride (75 mg/kg i.m.) and medetomidine hydrochloride (0.4 mg/kg s.c.) and supplemented with ketamine as needed. A single intravenous catheter was implanted into the right jugular vein aimed at the left vena cava. Catheters (Camcaths, UK) consisted of a 22 g cannula attached to silastic tubing (0.012 ID) and fixed to nylon mesh. The mesh end of the catheter was sutured s.c. on the dorsum. Carprofen (50 mg/kg) was administrated for pain relief once before and twice after surgery. Gentamycin (5 mg/kg) was administered before surgery and for 5 days post-surgery. Animals were allowed 7–9 days to recover from surgery.

Apparatus

Operant conditioning chambers (29.5 × 24 × 25 cm; l × w × h; Med Associates, USA), situated in light- and sound-attenuating cubicles equipped with a ventilation fan were used. Each chamber contained two retractable levers. A cue light was present above each lever and a house light was located on the opposite wall. Priming infusions of cocaine were never given. After each session, catheters were flushed with 0.15 ml heparinized saline. Experimental events and data recording were controlled using MED-PC for Windows.

Intravenous cocaine self-administration

Cocaine self-administration was performed as previously described (Veeneman et al. 2012a; -2012b).

Fixed ratio-1 schedule of reinforcement

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine under a fixed ratio-1 (FR-1) schedule of reinforcement for 10 consecutive sessions. During 2 hr sessions, two levers were present, one of which was designated as active. The position of the active and inactive levers was counterbalanced between animals. Pressing the active lever resulted in the infusion of 0.1 ml of a cocaine solution over 5.6 sec, retraction of the levers, switching off of the house light, followed by a 20 sec time-out period. During the infusion, the cue light above the lever was illuminated. To assess the sensitivity of the animals to acquire cocaine self-administration, we used a dose of 0.083 mg/infusion (which is threefold lower than our usual training dose of 0.25 mg/infusion) during the first 5 self-administration sessions, followed by 5 sessions in which our usual unit dose of cocaine was available, i.e., 0.25 mg/infusion. Responding on the inactive lever was recorded, but had no programmed consequences.

FR-1 dose-response curve

After 10 sessions of acquisition of cocaine self-administration, the animals received two more sessions under the FR-1 schedule of reinforcement to verify that responding had stabilized. Next, the rats were tested in a within-session dose-response self-administration session. To circumvent confounding effects of the initial loading phase of cocaine on responding, the dose-response session started with 30 minutes of self-administration of 0.25 mg/infusion cocaine. Subsequently, the animals were allowed to respond for descending doses of cocaine (0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.063, 0.031 mg/infusion). Pressing the active lever resulted in the infusion of cocaine in 0.1 ml saline over 5.6 sec, retraction of the levers, switching off of the house light, followed by a 20 sec time-out period. During the infusion, the cue light above the lever was illuminated. Each dose was available for 1 hr and the introduction of a new dose was preceded by a 10 minute time-out period. Responding on the inactive lever was recorded, but had no programmed consequences.

Progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement

After restabilization of cocaine self-administration under the FR-1 schedule of reinforcement, rats underwent two sessions of cocaine self-administration under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement. PR sessions started with the illumination of the house light and insertion of the active and inactive lever. Under this schedule, animals had to meet a response requirement on the active lever that progressively increased after every earned reward (1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, etc; Richardson and Roberts 1996). When rats met the response requirement on the active lever, this led to a cocaine infusion of 0.083 mg/infusion during the first PR session and 0.25 mg/infusion during the second PR session, retraction of both levers, switching off of the house-light, and illumination of the cue-light for the duration of the infusion. This was followed by a 10 min time-out period to reduce the influence of cocaine-induced psychomotor effects on responding for the next infusion, during which both levers remained retracted. After the time-out period, the cycle re-started with the insertion of both levers and illumination of the house-light. Sessions continued until rats failed to obtain a cocaine infusion within one hour. The highest number of active responses an animal performed for one single cocaine infusion was defined as the breakpoint. Responding on the inactive lever was recorded, but had no programmed consequences.

Cue, cocaine and yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking

After completion of the PR experiment, rats underwent a 1 hr extinction session during which all procedures were identical to those used during the self-administration phase, except that the drug syringes were removed from the infusion pumps (day 1). Thus, pressing the active lever resulted in the illumination of the cue-light (5.6 seconds), retraction of the levers, switching off of the house light, followed by a 20 sec time-out period, but without the delivery of a cocaine infusion. To assess cue-induced cocaine seeking, and the occurrence of incubation of cocaine seeking (Grimm et al. 2001), the same procedure was repeated 14 days later. During the period in between the cue-induced cocaine seeking tests, rats were kept in their home cage and handled once weekly. After the second test for cue-induced cocaine seeking, 10 consecutive extinction sessions (2 hours) were conducted in which all procedures were identical to those used during the self-administration phase, except that the drug syringes were removed from the infusion pumps. Next, rats were tested for reinstatement induced by cocaine injections (0, 5, and 10 mg/kg, IP) during three 1-h test sessions that were separated by 10 min time-out period. Saline and cocaine injections were given immediately prior to the test sessions in an ascending order to minimize carry-over effects of residual cocaine. Finally, the effect of treatment with yohimbine (0, 0.75, and 1.5 mg/kg, IP) on reinstatement of cocaine seeking behaviour was determined during three 1-h test sessions that were separated by 30 min. Vehicle or yohimbine was injected 30 min prior to the start of the test sessions. During all reinstatement sessions, procedures were identical to those used during the self-administration phase, except that the drug syringes were removed from the infusion pumps. Responding on the inactive lever was recorded, but had no programmed consequences. Regular 2-h extinction sessions were given during the intervening days between cocaine- and yohimbine reinstatement tests.

Drugs

Cocaine-HCl was purchased from Bufa BV (The Netherlands) and dissolved in sterile physiological saline (0.9% NaCl). Yohimbine hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma (The Netherlands) and dissolved in distilled water.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means and standard errors of the mean (S.E.M) and analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 15.0. Data were analyzed by two-factor repeated-measures ANOVAs with session (acquisition, extinction), dose (dose response), dose (cocaine- and yohimbine-induced reinstatement) or day (cue-induced reinstatement) as within-subjects variables, and rearing condition (SOC-ISO) as between-subjects variables. For the acquisition of cocaine self-administration experiments, two separate analyses were performed: session 1–5 (acquisition of self-administration of 0.083 mg/infusion) and session 6–10 (self-administration of 0.25 mg/infusion). In case of statistically significant main effects, further post hoc comparisons were conducted using Paired samples or Student t-tests. Breakpoints in the PR experiments are derived from an escalating curve, which violates the homogeneity of variance. Therefore, we analyzed breakpoints using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test. For all statistical analyses the level of probability for significant effects was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Acquisition of cocaine self-administration

First, we assessed the effect of early social isolation on the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in adulthood. Cocaine self-administration at 0.083 mg/infusion under a FR-1 schedule of reinforcement (sessions 1–5) is shown in figure 1. Social isolation significantly enhanced cocaine self-administration. Thus, the number of earned rewards was higher in ISO rats (group: [F(1,25)=8.01, p<0.01]; session: [F(4,25)=12.31, p<0.001]; group*session: [F(4,100)=4.92, p=0.01]; figure 1A). Post-hoc analysis showed a significant difference in number of rewards between SOC and ISO rats for sessions 3 to 5. In contrast, early social isolation had no effect on inactive lever presses during the first 5 sessions (group: [F(1,25)=1.27, NS]; data not shown). For the next 5 sessions (session 6 to 10), the rats were trained to self-administer cocaine at a dose of 0.25 mg/infusion (figure 1A). The ISO rats responded more than controls for this unit dose of cocaine during sessions 6 to 8 (group: [F(1,25)=12.39, p<0.05]; session: [F(4,25)=0.11, NS]; group*session: [F(4,100)=7.63, p<0.001]; figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Effects of social isolation during PND 21–42 followed by re-socialization on acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration at 0.083 mg/infusion (session 1–5) and 0.25 mg/infusion (session 6–10) in adulthood. (A) The number of rewards (2 hr) and (B) intake of cocaine (mg/2 hr) during the first 10 cocaine self-administration sessions. (C) Number of rewards during the 5th session and (D) 10th session expressed in 20 min bins. SOC=socially reared rats during PND 21–42 (n=13), ISO=socially isolated rats during PND 21–42 (n=14). Data represents mean+SEM. * p<0.05 compared to SOC

Analysis of cocaine intake during the acquisition of self-administration revealed comparable results as response levels (figure 1B). Cocaine intake was significantly enhanced in ISO rats during both the first 5 (0.083 mg/infusion) and second 5 (0.25 mg/infusion) cocaine self-administration sessions (session 1–5: group: [F(1,25)=8.01, p<0.05]; session: [F(4,25)=12.31, p<0.05]; group*session: [F(4,100)=4.92, p<0.05]; session 6–10: (group: [F(1,25)=12.39, p<0.05]; session: [F(4,25)=0.11, NS]; group*session: [F(4,100)=7.63, p<0.001]). Post-hoc analyses showed that cocaine intake was higher in the ISO rats during sessions 3 to 8.

Response patterns during the 5th self-administration session (0.083 mg/infusion) showed that ISO rats earned a higher number of rewards throughout the session (time: [F(5,125)=10.00, p<0.05]; group: [F(1,25)=20.47, p<0.05]; time*group: [F(5,125)=1.16, p<0.05]; figure 1C). In contrast, analysis of the response patterns during the 10th session (0.25 mg/infusion) showed no difference between groups (time: [F(5,125)=26.8, p<0.05]; group: [F(1,25)=2.36, NS], time*group: [F(5,125)=0.87, p<0.05]; figure 1C).

Cocaine self-administration: dose response analysis

Next, we examined the effects of early social isolation on the sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of cocaine. To that aim, a within-session dose-response protocol was used (figure 2). First, the rats were allowed a loading phase of 0.25 mg/infusion for 30 min. During this loading phase, there was no difference in the number of rewards and inactive lever responses between SOC and ISO rats (data not shown). Analysis of the dose response function revealed that the number of infusions taken [dose: F(4,22)=161.19, p<0.001] (figure 2A) as well as the total amount of drug administered [dose: F(4,22)=124.67, p<0.001] (figure 2B) was a function of the unit dose of cocaine. However, the dose-response relationship revealed no effect of social isolation (rewards: group: [F(1,22)=0.20, NS]; dose*group: [F(4,88)=0.37, NS]; cocaine intake: group: [F(1,22)=0.06, NS]; dose*group: [F(4,88)=0.29, NS]). There was no effect of unit dose on the inactive lever responses [F(4,22)=1.19, NS] (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of social isolation during PND 21–42 followed by re-socialization on within-session dose response curve of cocaine self-administration in adulthood. Graphs illustrate (A) the number of cocaine infusions (rewards) and (B) cocaine intake (mg/hr). SOC=socially reared rats during PND 21–42 (n=12), ISO=socially isolated rats during PND 21–42 (n=12). Data represents mean+SEM.

Cocaine self-administration under a PR schedule of reinforcement

To examine whether early social isolation affected the motivation for cocaine in adulthood, we evaluated the effects on responding for two unit doses of cocaine under a PR schedule of reinforcement. Responding for 0.083 mg/infusion was tested (figure 3A) followed by responding for 0.25 mg/infusion (figure 3B). Breakpoints under the PR schedule of reinforcement were increased in ISO rats compared with SOC rats for both unit doses (0.083 mg/infusion: U=34, p<0.05; 0.25 mg/infusion: U=15, p<0.01) (figure 3A–B), with no effect on inactive lever presses (0.083 mg/infusion: U=64, NS; 0.25 mg/infusion: U=47.5, NS) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of social isolation during PND 21–42 followed by re-socialization on breakpoints under a PR schedule of reinforcement at (A) 0.083 mg/infusion of cocaine or (B) 0.25 mg/infusion of cocaine in adulthood. SOC=socially reared rats during PND 21–42 (0.083 mg/infusion: n=12; 0.25 mg/infusion: n=11), ISO=socially isolated rats during PND 21–42 (0.083 mg/infusion: n=13; 0.25 mg/infusion: n=11). Data represents mean+SEM. * p<0.05 compared to SOC

Extinction and cue, drug and yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking

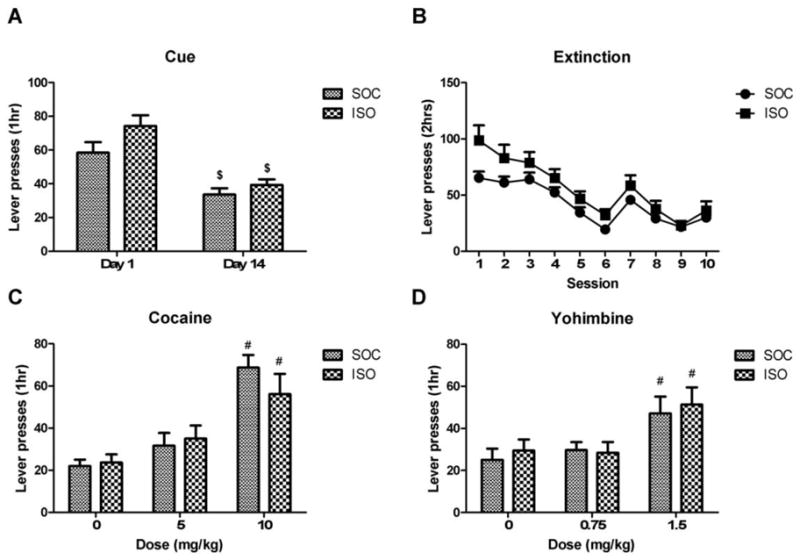

The findings that early social isolation enhanced acquisition of cocaine self-administration (figure 1) and the motivation to respond under a PR schedule of reinforcement (figure 3) in adulthood raised the question whether early social isolation affected the sensitivity to reinstatement of cocaine seeking. First, we tested the effect of early social isolation on cue-induced cocaine seeking and its incubation. Therefore, responses were recorded 1 day and 14 days after withdrawal during which cocaine infusions were withheld. Figure 4A depicts the number of non-reinforced responses on the lever previously associated with cocaine, on day 1 and day 14 in the presence of the house light and cue lights that were previously associated with cocaine availability. Responding for drug-associated stimuli decreased between day 1 and day 14 [day: F(1,20)=41.04, p<0.05] (figure 4A). Analysis of responses revealed no effect of early social isolation on cue-induced cocaine seeking (day 1 [t(20)=−1.78, NS]; day 14 [t(20)= −1.13, NS]; day*group [F(1,20)=1.19, NS]).

Figure 4.

Effects of social isolation during PND 21–42 followed by re-socialization on (A) cue-induced cocaine seeking, (B) extinction of cocaine self-administration, (C) cocaine- and (D) yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in adulthood. SOC=socially reared rats during PND 21–42 (n=11), ISO=socially isolated rats during PND 21–42 (n=11). Data represents mean+SEM. $ p<0.05 compared to day 1, # indicates p<0.05 compared to 0 mg/kg.

Next, we determined whether early social isolation affected extinction of cocaine self-administration in adulthood. Figure 4B represents the responses on the active lever during 10 consecutive extinction sessions. Both SOC and ISO rats showed a gradual decrease in responses on the active lever responses across sessions (session: [F(9,180)=33.19, p<0.05]). However, no difference between the groups was found (group: [F(1,20)=3.78, NS]; group*session: [F(9,20)=1.43, NS]). Throughout the extinction sessions, the inactive lever responses remained low, but changed significantly across sessions (group*session: [F(9,180)=4.53, p<0.05]), with no difference between groups (group: [F(1,20)=0.01, NS]) (data not shown).

After extinction of cocaine self-administration, we examined cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Ascending doses of cocaine (0, 5, 10 mg/kg) were administered according to a within-session protocol. As shown in figure 4C, cocaine priming increased responding on the active lever (dose: [F(2,20)=29.06, p<0.05]), but not on the inactive lever (dose: [F(2,40)=2.40, NS]) (data not shown). Post-hoc analysis showed that this effect was significant at 10 mg/kg cocaine for both groups (SOC [t(10)=−8.47, p<0.05], ISO [t(10)=−3.15, p<0.05]). No differences were observed between SOC and ISO rats in cocaine-induced reinstatement to cocaine seeking behaviour (group: [F(1,20)=0.17, NS]; group*dose: [F(2,40)=1.33, NS]).

We then assessed whether early social isolation affected stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking behaviour. To that aim, animals received intraperitoneal injections of the pharmacological stressor yohimbine in ascending doses (0, 0.75 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg) according to a within-session protocol. There was a main effect of yohimbine on responding on the active lever (dose: [F(2,40)=16.04, p<0.05]) (Figure 4D). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase of yohimbine-induced responding at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg (SOC [t(10)=−3.68, p<0.05], ISO [t(10)=−2.90, p<0.05]), but early social isolation had no effect on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (group: [F(1,20)=0.17, NS]; group*dose: [F(2,40)=0.28, NS]. Moreover, yohimbine had no effect on responding on the inactive lever [F(2,40)=1.25, NS] (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, we show that deprivation of social contact in rats during a developmental time window characterized by high levels of social play behaviour (PND 21–42), results in enhanced acquisition of cocaine self-administration in adulthood. Dose-response analysis did not reveal changes in the sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of cocaine, but early social isolation increased the motivation for cocaine self-administration under a PR schedule of reinforcement. Extinction of cocaine self-administration or cue, cocaine and stress-induced reinstatement were not affected by early social isolation. Of note, these changes in the sensitivity to self-administered cocaine were seen even though the animals were resocialized for six weeks in between social isolation and cocaine self-administration. Together, these data show that early social isolation causes a long-lasting increase in the motivation to self-administer cocaine in adulthood.

In general, the effects of environmental manipulations or drug treatment on acquisition of self-administration are more likely to be detected when low unit doses of drugs are used (Lu et al. 2003; Piazza et al. 1996; Vezina et al. 2002). Therefore, we studied acquisition of cocaine self-administration at a dose threefold lower (0.083 mg/infusion) than our usual training dose. We found that ISO rats showed profoundly higher rates of responding during acquisition of cocaine self-administration. These findings are consistent with previous findings showing enhanced acquisition of self-administration of a low dose of cocaine (0.083 mg/kg/infusion) in isolation-reared rats (Howes et al. 2000). Remarkably, acquisition of self-administration of a higher dose of cocaine (1.5 mg/kg/infusion) was retarded in isolation reared rats (Howes et al. 2000; Phillips et al. 1994a), suggesting that the dose-response curve for acquisition of cocaine self-administration was shifted to the left after isolation rearing. However, in another study (Gipson et al. 2011, see also Ding et al. 2005), enhancement of the acquisition of cocaine self-administration was more pronounced at a medium dose (0.5 mg/kg/infusion) compared to a lower dose of cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion). Since we tested only one unit dose of cocaine, we can not speculate on changes in the dose-response curve of acquisition of cocaine self-administration. However, our findings do identify the first weeks post-weaning as a critical period in development that determines sensitivity to acquire cocaine use.

While our findings on acquisition of cocaine self-administration resonate well with previous data from isolation rearing studies (Ding et al. 2005; Gipson et al. 2011; Howes et al. 2000; Phillips et al. 1994a), our dose-response analysis does not. That is, we found no effect of early social isolation, whereas isolation rearing studies have consistently found differences in the dose-response function of cocaine self-administration, albeit that the direction of the effect differed between these studies (Boyle et al. 1991; Phillips et al. 1994a; Schenk et al. 1987). The most likely explanation for these differential findings is that the developmental period that determines sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of cocaine does not lie within the restricted period of social isolation used in the present study. Indeed, during the last two acquisition sessions, when animals responded for 0.25 mg/infusion of cocaine, there were no differences in cocaine self-administration between the SOC and ISO groups, suggesting that it is the acquisition of cocaine self-administration, rather than the reinforcing properties of cocaine that is facilitated by early social isolation. Combined, these findings raise the interesting possibility, to be tested in future studies, that social isolation during different periods in development causes a distinct pattern of neural adaptations that influence various aspects of addictive behaviour. Furthermore, the lack of effect of early social isolation on the dose-response function of cocaine self-administration indicates that the accelerated acquisition of cocaine self-administration and the higher motivation under a PR schedule of reinforcement are not merely the result of general increases in responding for the drug in the ISO rats.

Interestingly, when the willingness of the animals to respond for cocaine was tested under a PR schedule of reinforcement, we found profoundly increased breakpoints in the ISO rats. PR schedules of reinforcement assess the incentive motivational properties of reinforcers (Hodos 1961; Richardson and Roberts 1996). This increase in responding under a PR schedule was observed for both unit doses of cocaine, while responding for the drug within this dose range under an FR-1 schedule of reinforcement did not differ between the groups. This suggests that only when response requirements are high, ISO rats are more willing to respond for cocaine. Thus, early social isolation increases the incentive motivational properties of cocaine, rather than its reinforcing properties in general. The increases in responding during acquisition are not necessarily inconsistent with such an explanation, as increased motivation may also result in higher levels of responding during acquisition (see e.g. Veeneman et al. 2012b).

To the best of our knowledge, the influence of early social isolation or isolation rearing on extinction and reinstatement of responding for drugs has not previously been investigated. Our data show that social isolation during PND 21–42 has no repercussions for responding during extinction of cocaine self-administration, or the ability of cocaine-associated cues, a cocaine priming injection or treatment with the pharmacological stressor yohimbine to reinstate responding. Together, this pattern of effects indicates that social isolation during a social play-enriched developmental period causes a relatively specific change in the sensitivity to cocaine: the motivation for the drug is enhanced, but not its reinforcing properties, the persistence of responding, or the sensitivity to relapse. Remarkably, while drug seeking evoked by response-contingent presentation of drug-associated cues has repeatedly been shown to increase in the first weeks to months of abstinence (Grimm et al. 2001; Pickens et al. 2011), our data indicate the opposite, since cue-induced cocaine seeking actually decreased in both groups between the first and fourteenth day after the last self-administration session. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear, but at the very least it indicates that incubation of cocaine seeking does not invariably occur under all circumstances.

The pattern of effects reported here begs the question which long-lasting neural and behavioural adaptations are induced by three weeks of social isolation post-weaning. Studies on isolation rearing, in which animals are continuously isolated from weaning onwards (Robbins et al. 1996; Heidbreder et al. 2000; Fone and Porkess 2008), have revealed a host of neurobehavioural changes, many of which could contribute to increased motivation for cocaine, such as altered function of the mesolimbic dopamine system (Hall et al. 1998; Howes et al. 2000; Jones et al. 1992), which has been widely implicated in cocaine self-administration (Pierce and Kumaresan 2006; Wise 2004). However, in the present study animals were only isolated for three weeks post-weaning, which we presume induces a different, perhaps more restricted set of neurobehavioural changes. Neural changes induced by social isolation during PND 21–42 have been reported in several studies (e.g. Lukkes et al. 2009a; -2009b). Of particular relevance for the present data is a recent report showing that social isolation during PND 21–42 results in enhanced sensitivity of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons to NMDA receptor-induced long-term potentiation (Whitaker et al. 2013). This suggests that post-weaning social isolation enhances excitatory drive onto midbrain dopamine neurons. This may contribute to the enhanced motivation for cocaine, perhaps as a result of increased dopamine signaling within the nucleus accumbens shell, which has been implicated in both the acquisition of, and motivation for cocaine self-administration (Bari and Pierce 2005; Ikemoto 2003; Rodd-Henricks et al. 2002; Veeneman et al. 2012b).

We have recently shown, using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, that social isolation from PND 21–42 caused medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons to become insensitive to modulation of synaptic response amplitude by dopamine (Baarendse et al. 2013). Interestingly, the medial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in the acquisition of cocaine self-administration (Weissenborn et al. 1997), as well as in the motivation to respond for the drug (McGregor and Roberts 1995). Moreover, the medial prefrontal cortex exerts a prominent modulatory influence on activity of the mesoaccumbens dopamine system (e.g. Mitchell and Gratton 1992; for reviews see Heidbreder and Groenewegen 2003; Sesack and Grace 2010). Therefore, social isolation during development might alter dopamine activity in the nucleus accumbens as a result of disrupted prefrontal input into the mesoaccumbens dopamine system. Interestingly, the long-lasting disturbance in prefrontal function by early social isolation was accompanied by increased impulsive action and impaired decision making, in particular under challenging or novel circumstances (Baarendse et al. 2013). These long-lasting impairments in cognitive control may be related to the increased motivation for cocaine in socially isolated rats. Indeed, exaggerated impulsivity and decision making deficits have been associated with drug addiction (Bechara 2005; Dalley et al. 2011; Goldstein and Volkow 2011; Robbins et al. 2012; Verdejo-García et al. 2008). For example, impulsive action and impaired decision making have been identified as risk factors for drug and alcohol abuse in humans (Ersche et al. 2012; Goudriaan et al. 2011; Nigg et al. 2006) and animal studies have demonstrated that increased impulsive action predicts various aspects of addictive behaviour (Belin et al. 2008; Dalley et al. 2007; Diergaarde et al. 2008; Economidou et al., 2009). Together, these findings suggest that the increased motivation for cocaine induced by early social isolation is mediated by impairments in impulse control and decision making as a result of altered prefrontal cortex function.

In conclusion, our results show that the lack of proper social experiences during early post-weaning development profoundly enhances the motivation to take cocaine in adulthood. Thus, a dysfunctional social environment in childhood and adolescence may confer enhanced vulnerability to addictive behaviour in later life (Braun and Bock, 2011; Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009; Karelina and DeVries 2011).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA022628 (L.J.M.J.V.). We thank Yavin Shaham, Taco de Vries and Chris Pierce for advice on the design of the extinction-reinstatement experiment, and Mark H. Broekhoven for technical assistance.

References

- Baarendse PJJ, Counotte DS, O’Donnell P, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Early social experience is critical for the development of cognitive control and dopamine modulation of prefrontal cortex function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1485–1494. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Klebaur JE, Valone JM, Deaton C. Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous self-administration of amphetamine in female and male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:278–284. doi: 10.1007/s002130100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari AA, Pierce RC. 0 D1-like and D2 dopamine receptor antagonists administered into the shell subregion of the rat nucleus accumbens decrease cocaine, but not food, reinforcement. Neuroscience. 2005;135:959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle AE, Gill K, Smith BR, Amit Z. Differential effects of an early housing manipulation on cocaine-induced activity and self-administration in laboratory rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun K, Bock J. The experience-dependent maturation of prefronto-limbic circuits and the origin of developmental psychopathology: implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(Suppl 4):14–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Lääne K, Peña Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. 0 Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron. 2011;69:680–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diergaarde L, Pattij T, Poortvliet I, Hogenboom F, de Vries W, Schoffelmeer ANM, De Vries TJ. Impulsive choice and impulsive action predict vulnerability to distinct stages of nicotine seeking in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Kang L, Li B, Ma L. Enhanced cocaine self-administration in adult rats with adolescent isolation experience. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Robbins TW, Dalley JW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts relapse to cocaine-seeking after punishment-induced abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Jones PS, Williams GB, Turton AJ, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET. Abnormal brain structure implicated in stimulant drug addiction. Science. 2012;335:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1214463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagen R. Animal play behavior. Oxford University Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fone KC, Porkess MV. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents-relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1087–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson CD, Beckmann JS, El-Maraghi S, Marusich JA, Bardo MT. Effect of environmental enrichment on escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan AE, Grekin ER, Sher KJ. Decision making and response inhibition as predictors of heavy alcohol use: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1050–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham KL, Burghardt GM. Current perspectives on the biological study of play: signs of progress. Q Rev Biol. 2010;85:393–418. doi: 10.1086/656903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature. 2001;412:141–142. doi: 10.1038/35084134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Groenewegen HJ. The medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: evidence for a dorso-ventral distinction based upon functional and anatomical characteristics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:555–579. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Weiss IC, Domeney AM, Pryce C, Homberg J, Hedou G, Feldon J, Moran MC, Nelson P. Behavioral, neurochemical and endocrinological characterization of the early social isolation syndrome. Neuroscience. 2000;100:749–768. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134:943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes SR, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Leftward shift in the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in isolation-reared rats: relationship to extracellular levels of dopamine, serotonin and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala-striatal FOS expression. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s002130000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S. Involvement of the olfactory tubercle in cocaine reward: intracranial self-administration studies. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9305–9311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09305.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GH, Hernandez TD, Kendall DA, Marsden CA, Robbins TW. Dopaminergic and serotonergic function following isolation rearing in rats: study of behavioural responses and postmortem and in vivo neurochemistry. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:17–35. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90635-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karelina K, DeVries AC. Modeling social influences on human health. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:67–74. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Hall FS, Shaham Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:457–491. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkes JL, Mokin MV, Scholl JL, Forster GL. Adult rats exposed to early-life social isolation exhibit increased anxiety and conditioned fear behavior, and altered hormonal stress responses. Horm Behav. 2009a;55:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkes JL, Summers CH, Scholl JL, Renner KJ, Forster GL. Early life social isolation alters corticotropin-releasing factor responses in adult rats. Neuroscience. 2009b;158:845–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks-Kaufman R, Lewis MJ. Early housing experience modifies morphine self-administration and physical dependence in adult rats. Addict Behav. 1984;9:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JE, Marinelli M. Age matters. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:997–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor A, Roberts DCS. Effect of medial prefrontal cortex injections of SCH 23390 on intravenous cocaine self-administration under both a fixed and progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Behav Brain Res. 1995;67:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00106-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JB, Gratton A. Partial dopamine depletion of the prefrontal cortex leads to enhanced mesolimbic dopamine release elicited by repeated exposure to naturally reinforcing stimuli. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3609–3618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Czoty PW, Nader SH, Morgan D. Nonhuman primate models of social behavior and cocaine abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2012;224:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2843-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Peartree NA, Pentkowski NS. Emotional valence and context of social influences on drug abuse-related behavior in animal models of social stress and prosocial interaction. Psychopharmacology. 2012;224:33–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2853-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Wong MM, Martel MM, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, Adams KM, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:468–475. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199028.76452.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. The ontogeny of play in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1981;14:327–332. doi: 10.1002/dev.420140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Siviy SM, Normansell L. The psychobiology of play: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:465–492. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Pellis V. The Playful Brain: Venturing to the Limits of Neuroscience. One world Publications; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Smith PK. Physical activity play: the nature and function of a neglected aspect of playing. Child Dev. 1998;69:577–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: Interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic neurons. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:359–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens CL, Airavaara M, Theberge F, Fanous S, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GD, Howes SR, Whitelaw RB, Wilkinson LS, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Isolation rearing enhances the locomotor response to cocaine and a novel environment, but impairs the intravenous self-administration of cocaine. Psychopharmacology. 1994a;115:407–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02245084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GD, Howes SR, Whitelaw RB, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Isolation rearing impairs the reinforcing efficacy of intravenous cocaine or intra-accumbens d-amphetamine: impaired response to intra-accumbens D1 and D2/D3 dopamine receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology. 1994b;115:419–429. doi: 10.1007/BF02245085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:215–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potegal M, Einon D. Aggressive behaviors in adult rats deprived of playfighting experience as juveniles. Dev Psychobiol. 1989;22:159–172. doi: 10.1002/dev.420220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DCS. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD. Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Jones GH, Wilkinson LS. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of early social deprivation in the rat. J Psychopharmacology. 1996;10:39–47. doi: 10.1177/026988119601000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Cocaine is self-administered into the shell but not the core of the nucleus accumbens of Wistar rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:1216–1226. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Lacelle G, Gorman K, Amit Z. Cocaine self-administration in rats influenced by environmental conditions: implications for the etiology of drug abuse. Neurosci Lett. 1987;81:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)91003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Gorman K, Amit Z. Age-dependent effects of isolation housing on the self-administration of ethanol in laboratory rats. Alcohol. 1990;7:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Grace AA. Cortico-basal ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:27–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy SM, Panksepp J. In search of the neurobiological substrates for social playfulness in mammalian brains. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1821–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Okun AC, Neisewander JL. Social reward-conditioned place preference: A model revealing an interaction between cocaine and social context rewards in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Neisewander JL. Synergistic interaction between nicotine and social rewards in adolescent male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Baarendse PJJ, Vanderschuren LJMJ. The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Evaluating the rewarding nature of social interactions in laboratory animals. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1:444–458. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Conditioned place-preference induced by social play behavior: parametrics, extinction, reinstatement and disruption by methylphenidate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg CL, Hol T, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM, Everts H, Koolhaas JM. Play is indispensable for an adequate development of coping with social challenges in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1999;34:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ. How the brain makes play fun. Am J Play. 2010;2:315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Niesink RJM, Van Ree JM. The neurobiology of social play behavior in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:309–326. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeneman MMJ, van Ast M, Broekhoven MH, Limpens JHW, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Seeking-taking chain schedules of cocaine and sucrose self-administration: effects of reward size, reward omission, and α-flupenthixol. Psychopharmacology. 2012a;220:771–785. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2525-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeneman MMJ, Broekhoven MH, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Distinct contributions of dopamine in the dorsolateral striatum and nucleus accumbens shell to the reinforcing properties of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012b;37:487–498. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina P, Lorrain DS, Arnold GM, Austin JD, Suto N. Sensitization of midbrain dopamine neuron reactivity promotes the pursuit of amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4654–4662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04654.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenborn R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Effects of medial prefrontal or anterior cingulate cortex lesions on responding for cocaine under fixed-ratio and second-order schedules of reinforcement in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:242–257. doi: 10.1007/s002130050447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker LR, Degoulet M, Morikawa H. Social deprivation enhances VTA synaptic plasticity and drug-induced contextual learning. Neuron. 2013;77:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KA, Gobrogge KL, Wang Z. The role of mesocorticolimbic dopamine in regulating interactions between drugs of abuse and social behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:498–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]