Abstract

Sexual assault survivors receive various positive and negative social reactions to assault disclosures, yet little is known about mechanisms linking these social reactions to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and problem drinking. Data from a large, diverse sample of women who had experienced adult sexual assault was analyzed with structural equation modeling to test a theoretical model of the relationships between specific negative social reactions (e.g., controlling, infantilizing) and positive reactions (e.g., tangible support), perceived control over recovery, PTSD, and drinking outcomes (N = 1863). A model disaggregating controlling reactions from infantilizing reactions showed that infantilizing reactions in particular related to less perceived control, which in turn was related to more PTSD and problem drinking, whereas controlling reactions were not related to perceived control, PTSD, or problem drinking. Tangible support was related to increased perceived control over recovery, yet it was not protective against PTSD or problem drinking. Finally, PTSD and drinking to cope fully mediated the effect of perceived control on problem drinking. Implications for practice and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: sexual assault, PTSD, perceived control, social reactions, drinking

Sexual assault is associated with long-term negative outcomes such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and problem drinking (Stewart & Israeli, 2002). Social and psychological variables may intervene after the sexual assault to either ameliorate or exacerbate these negative effects (see Ullman, 2010 for a review). The mechanisms through which specific social reactions impact assault-related health outcomes are still being explored. For example, positive and negative social reactions impact recovery via psychological mediators such as coping and self-blame (e.g., Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007). In the present study we test whether perceived control over the recovery process mediates the relationship between social reactions to sexual assault disclosure and health outcomes such as PTSD and problem drinking. Rape is traumatic in part because it entails a significant loss of control over one’s body during the assault (Ullman, 2010). Negative reactions such as trying to control the victim’s choices or infantilizing the victim can further reduce feelings of control over one’s recovery, and in turn increase PTSD symptoms and the need to drink to cope with symptoms. Conversely, tangible support can empower women to feel in control of their recovery, decrease PTSD symptoms, and reduce the need to drink to escape PTSD symptomatology. Thus, we predicted that perceived control would mediate the effects of social reactions on PTSD, which in turn would affect drinking to cope and problem drinking.

In support of our theoretical model, we draw upon findings that (a) unsupportive social reactions are negatively related to perceived control (Frazier et al., 2011), (b) perceived control relates to less distress and less social withdrawal in sexual assault survivors (Frazier, Mortensen, & Steward, 2005), (c) perceived control negatively predicts PTSD symptoms and binge drinking (Frazier, 2003; Frazier et al., 2011; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2007), and (d) PTSD and problem drinking are highly comorbid (Stewart & Israeli, 2002), and drinking to cope mediates the relation of PTSD with alcohol abuse (Ullman et al., 2005 Yeater, Austin, Green, & Smith, 2010).

Social Reactions to Assault Disclosure

As many as 92% of sexual assault survivors disclose the assault to at least one person (Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Starzynski, Ullman, Filipas, & Townsend, 2005; Ullman & Filipas, 2001), and most of them receive a mixture of positive and negative reactions (Filipas & Ullman, 2001; Starzynski et al., 2005). Of these reactions, two specific types might be particularly relevant to victims’ perceived control over recovery: tangible support and controlling/infantilizing reactions. Receiving practical, tangible support such as advice, resources, or shelter can significantly increase victims’ feelings of efficacy in dealing with the assault. Attempts to help, however, can easily cross the line into attempts to make decisions for the victim, and to control her actions. For example, pressuring the victim to file a police report is different from offering to help her through the process, hut leaving the choice to her. Unwanted attempts to help or control the victim can also lead to infantilizing attitudes, or treating the victim as if she were a child or incapable of dealing with the assault by herself. Thus, tangible support and controlling or infantilizing reactions have common roots – believing that the victim needs help with the recovery process – but can have very positive or negative effects, respectively, on victims’ perceived control over recovery.

Research from health psychology shows that social support in the form of practical help increases feelings of self-efficacy, which in turn improves health outcomes (e.g., Chlebowy & Garvin, 2006). In the context of sexual assault, tangible support includes spending time with the survivor, taking her to police or medical providers, giving her a place to stay, or giving her resources following an assault. Tangible support and advice can have a positive effect on health outcomes by increasing victims’ perceived control over their recovery process (that is, their perceived self-efficacy for coping with the assault).

Negative responses to sexual disclosure and their effects on victims’ well-being are less clear-cut. Infantilizing reactions such as patronizing the victims or treating them as if they were irresponsible are perceived by victims as unequivocally bad and hurtful (Campbell et al., 2001). Controlling reactions such as pushing victims to tell the police, however, can be experienced as either helpful, well-intended, and active involvement (Campbell et al., 2001), or as harmful attempts to control their lives and decisions (Ullman, 2000). These two types of reactions might have different effects on coping and recovery (e.g., Campbell, Ahrens, Sefl, Wasco, & Barnes 2001; Littleton & Breitkopf, 2006). Although sometimes categorized as negative, (Ullman, 2000), controlling reactions can be perceived as helpful by some victims (Campbell et al., 2001), because their subjective interpretation depends on who provided the reaction (Ahrens, Cabral, & Abeling, 2009), and probably on the specific circumstances of the reactions. For example, the reaction of trying to control the victims’ decisions was perceived as hurtful by 68% of women (still a majority), but helpful by 27%. On the other hand, minimizing and infantilizing reactions were .perceived as harmful and negative by all victims (Ahrens et al., 2009). Therefore, it is important to explore whether the two types of reaction actually measure two different constructs, and should be considered separately, especially in light of their differential effects on victims’ subjective perceptions of helpfulness.

Mechanisms through Which Social Reactions Can Affect Drinking

Perceived control over recovery

Rape is traumatic because it entails a significant loss of control over one’s body during the assault, and can lead to decreased perceptions of personal safety, increased feelings of vulnerability, and lower perceived control and self efficacy (Janoff-Bulman, 1997; Perloff, 1983; Schepple & Bart, 1983). There is consistent evidence that attributions of present control, specifically perceived control over the recovery process, is associated with fewer PTSD symptoms in sexual assault survivors (Frazier, 2003; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Ullman et al., 2007b). In one sample of sexual assault survivors, present control (control over the recovery process) was associated with less distress partly because it was associated with less social withdrawal and more cognitive restructuring in sexual assault survivors (Frazier et al., 2004). Perceived present control over recovery from a stressful event (not necessarily sexual assault) was also found to be negatively associated with binge drinking in college students (Frazier et al., 2011), suggesting that perceived control over recovery might relate to less problem drinking for sexual assault survivors. Given that the relation between PTSD and general distress (both related to perceived control) and problem drinking has been established by past research, the role of perceived control in an explanatory model of problem drinking is worth exploring. In addition, research has yet to examine whether perceived control over recovery mediates the effects of other factors such as controlling (versus helpful) social reactions on PTSD and problem drinking.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is a common psychological consequence of sexual assault with 16-60% of victims developing the disorder (Elliott, Mok, & Briere, 2004; Kilpatrick, Edmunds, & Seymour, 1992; Resnick et al., 2000). Various studies show that negative social reactions to assault disclosure are positively related to PTSD symptoms (Littleton, 2010; Ullman, 2000; Ullman et al., 2007) and two meta-analyses found that social support was the strongest predictor of PTSD (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). The deleterious effect of negative social reactions is stronger than the protective effect of positive reactions, with the latter tending to be small or not significant (e.g., Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2006). In some cases, tangible support was even positively related to psychological symptoms (Ullman, 1996), perhaps because victims disclosing to more people typically get a mix of both positive and negative reactions (Ullman, 2010). Ullman and colleagues (2007) also found that perceived control over recovery has an important role in predicting PTSD symptom severity, by being the only protective factor (i.e., the only negative predictor) against PTSD. Thus, we hypothesized that controlling reactions would relate to decreased perceived control, and in turn increased PTSD, and that tangible support would relate to increased perceived control, although not necessarily to decreased PTSD (Ullman, 1996).

Drinking to cope and problem drinking

Sexual assault survivors are at higher risk of problem drinking than the general population (Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997; Wilsnack, Vogeltanz, Klassen, & Harris, 1997). One of the mechanisms through which sexual assault leads to problem drinking is drinking to cope with negative emotions (or to increase positive emotions), at least in the case of child sexual assault (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). In addition, PTSD and problem drinking are highly comorbid, especially in female victims (Stewart & Israeli, 2002). Research suggests that increased drinking to cope may mediate the PTSD-drinking relationship (Epstein, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 1998; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005).

As for the role of social reactions, problem drinkers received more negative social reactions post-assault than non-problem drinkers (Ullman, Starzynski, Long, Mason, & Long, 2008). Women with comorbid PTSD and problem drinking also received more negative social reactions than women with PTSD alone, and better social support was related to less comorbidity, which potentially acts as a protective factor (Ullman et al., 2005). We thus expected negative reactions to be related to more problem drinking and that this relationship would be mediated by perceived control, PTSD, and drinking to cope.

Based on previous literature and theory, we also predicted that PTSD symptoms will act as a partial mediator between perceived control and problem drinking: Women with less perceived control will be more likely to experience PTSD symptoms, and to turn to drinking to cope as a self-medicating mechanism to deal with distress.

Method

Sample

A sample of volunteer women (N = 1863) from the Chicagoland area, age ranging from 18 to 71 (M = 31.1, SD = 12.2), completed a mail survey. The sample was ethnically diverse (45% African-American, 35% White, 2% Asian, 18% other; 14% Hispanic, assessed separately). The sample was well-educated with 34.6% having a college degree or higher, 43.5% having some college education, and 21.9% having a high school education or less. Just under half of the sample (46.8%) was currently employed, although income levels were relatively low, with 68% of women having household incomes of less than $30,000.

Our sexual victimization measure was a modified version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES, Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987) created by Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss (2004). The measure revealed that 80% of victims experienced completed rape, 7% attempted rape, 8% coercion, 4% unwanted contact, and 1% did not endorse any SES items. On average, women had experienced the assault 14 years before taking the survey (SD = 12.22, Mdn = 11).

Procedure

Recruitment was accomplished via weekly advertisements in local free newspapers, on Craigslist, and through university mass mail. In addition, we posted fliers in the community, at other Chicago colleges and universities, as well as at agencies that cater to community members in general and victims of violence against women specifically (e.g., community centers, cultural centers, substance abuse clinics, domestic violence and rape crisis centers). We attempted to cover a large area and include different neighborhoods with our fliers, and to reach a varied sample of victims. The fliers and ads mentioned that participants would be paid for completing the survey; however the amount was not specified. Interested women called the research office and were screened for eligibility using the following criteria: a) had an unwanted sexual experience at the age of 14 or older, b) were 18 or older at the time of participation, and c) had previously told someone about their unwanted sexual experience. Women were also informed about the $25 compensation at this time. We sent eligible participants packets containing the survey, an informed consent form, a list of community resources for dealing with victimization, and a stamped return envelope for the completed survey. Participants were paid upon receipt of their completed surveys. The response rate was 85%. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and documents.

Measures

Social reactions to disclosure

Women completed the Social Reactions Questionnaire (SRQ; Ullman, 2000), reporting how often they received 48 different social reactions from any support provider since the assault on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The SRQ consists of seven subscales detailing various types of negative (controlling, blaming, egocentric responses, distracting the victim, or treating the victim differently) and positive (emotional support and tangible support) reactions to assault disclosure. Overall, women received more good (M = 2.22, SD = 0.95) than bad (M = 0.96, SD = 0.80) reactions, with emotional support being the most common reaction (M = 2.51, SD = 1.00) and blaming the victim the least common (M = 0.79, SD = 1.08).

Because not all scales were directly relevant to perceived control over recovery, and because we were primarily interested in the differential effects of helping versus controlling the victim, we focused on two of these subscales. Specifically, our models only include the frequency with which participants received tangible support on a 5-item subscale (e.g., “Helped you get information of any kind about coping with the experience”; “Helped you get medical care”) and controlling/ infantilizing reactions (e.g., “Tried to take control of what you did/ decisions you made”; “Treated you as if you were a child or somehow incompetent”). On average, women reported “rarely” receiving tangible support (M = 1.34, SD = 1.16) and controlling reactions (M = .86, SD = .91). Both scales were reliable with Cronbach’s alphas of .82 for controlling responses and .79 for tangible support.

Further, we separated the controlling/ infantilizing 5-item subscale into controlling and infantilizing reactions (Relyea & Ullman, 2012; Littleton & Breitkopf, 2006) to separate their potentially different effects on our mediators and outcomes. The new subscales had acceptable reliability: controlling (Cronbach’s alpha = .69) and infantilizing (Cronbach’s alpha = .77).

Perceived control over recovery

Women completed the seven-item present control subscale of the Rape Attribution Questionnaire (Frazier, 2003). They indicated perceived control over recovery in the past year on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), M = 3.60, SD = .78 (e.g., “There are things I can do to lessen the effects of the assault”). Frazier (2003) reported an average alpha of .75 for present control over recovery from assault across four time periods in one year. The scale was also reliable in our sample, Cronbach’s α = .78.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms associated with sexual assault

PTSD symptoms were assessed with the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995), a standardized 17-item instrument based on DSM-IV criteria. On a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost always), women rated how often each symptom (i.e., reexperiencing/intrusion, avoidance/ numbing, hyperarousal) bothered them in relation to their most serious sexual assault during the past 12 months. The PDS has acceptable test–retest reliability for a PTSD diagnosis in assault survivors over two weeks (κ = .74; Foa et al., 1997). The 17 items were summed to assess the extent of posttraumatic symptomatology (M = 21.13, SD = 12.93, α = .93 in this sample). Sixty three percent qualified for the PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity scores were: none (3.8%), mild (19.5%), moderate (27.2%), moderate to severe (34%), and severe (15.5%) using Foa’s (1995) scoring criteria that correspond for PTSD in DSM-IV.

Drinking to cope

Women rated the relative frequency of drinking to cope with negative emotions on a 5-item, 4-point scale ranging from 0 (I didn’t do this at all) to 3 (I did this a lot) (e.g., “I drank to forget my worries”, Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). The scale was reliable in the initial sample reported by Cooper and colleagues, α = .84 and in the current sample, α = .92. Overall, women reported little to medium use of alcohol to cope (M = 1.19, SD = 0.94).

Problem drinking

Past-year problem drinking was assessed with the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST, Selzer, 1971), a widely used 25-item standardized self-report screening instrument for alcohol abuse and dependence. The scale consists of a checklist of alcohol abuse-related behaviors (e.g., attending AA meetings, getting into fights while drinking, having family members complain, etc.). The number of problematic behaviors checked “yes” was treated as a continuous measure of problem drinking, with multiple drinking-related arrests counting as one problem each. Therefore, the range in our study was 0 to 32 (M = 2.90, SD = 4.22, α =.80). Although women who indicated they had not drank at all in the past year (N = 427) were instructed to skip the MAST, but were coded as 0 so that we could include them in the analyses. This allowed us to keep the entire sample, instead of selecting only women who were drinking in the year before taking the survey Thus, both women who drank in the past year but had none of the behaviors described in this scale, and women who had not drank in the past year, were coded as 0 (N = 652).

Results

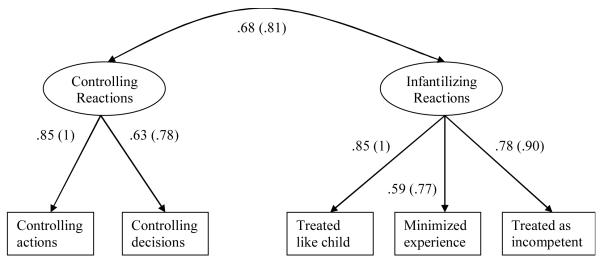

First, we investigated the possibility that the controlling reactions subscale of the SRQ is better described as a combination of two separate constructs, yielding two subscales: pure controlling reactions and infantilizing reactions. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis in Mplus to compare model fit for a one-factor solution and a two-factor solution. To scale the factors, we fixed the first item at 1.00 for each factor in both analyses.

Overall, women reported experiencing each type of social reaction only rarely (means ranged from 0.78 to 1.09). In general, items were highly correlated, with higher correlations between items that would theoretically load together in a two-factor solution (See Figure 1 notes). The one-factor model did not fit the data well, χ2 (5, N = 1830) = 230.56, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .17, SRMR = .06, although all loadings were significant and ranged from moderate to high (.49 to .83). The two-factor model included the two pure controlling reactions items loading on one factor, and the three infantilizing items loading on a second factor. We allowed the two factors to correlate, as these types of reactions were expected to covary in the population. Indeed, the two factors were highly correlated at .68. The two-factor solution had a much better fit, χ2 (4, N = 1863) = 8.71, p > .05, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .008. The two-factor model also resulted in high loadings on each factor (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Two-factor model of controlling and infantilizing reactions subscales to the Social Reactions Questionnaire. Numbers represent standardized coefficients, with unstandardized coefficient noted in parentheses. Individual item means ranged from 0.78 to 1.09, SDs 1.26 – 1.43. Inter-item correlations were significant and relatively high, especially between items loading on the same factor. Controlling victims’ actions and decisions were highly correlated, r = .53. Treating the victim like a child was highly correlated with minimizing the experience, r = .48, and treating the victim as incompetent, r = .66; minimizing the experience with treating the victim as incompetent, r = .48. Cross-factor correlations were generally lower (with some exceptions): controlling the victim’s decisions with treating the victim like a child, r = .36, minimizing the experience, r = .24, treating the victim as incompetent, r = .34; controlling the victim’s actions rs = .50, .33, .43, respectively.

To test our hypotheses, we used Mplus maximum likelihood estimation methods with bootstrapping to model the effects of social reactions, perceived control, PTSD, and drinking to cope on problem drinking. All measures were univariate normal with skew less than 3 and kurtosis less than 4 (Kline, 1998) except for the past–year MAST (problem drinking) score (k = 5.10). We used the untransformed variables, given that with larger samples effects of violations of normality assumptions regarding kurtosis are minimal (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Correlations between variables in the model were significant (r’s −.08 to .55, p’s < .01, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlations Between all Variables in the Models (Ns 1300 - 1750)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| 1. Controlling reactions scale | — | .78 | .89 | .30* | −.07* | .42* | .19* | .15* |

| 2. Controlling reactions | .50* | .36* | −.01 | .32* | .13* | .12* | ||

| 3. Infantilizing reactions | .14* | −.10* | .35* | .16* | .13* | |||

| 4. Tangible support | — | .14* | .25* | .08* | .09* | |||

| 5. Perceived control | — | −.18* | −.14* | −.08* | ||||

| 6. PTSD symptoms | — | .38* | .22* | |||||

| 7. Drinking to cope | — | .55* | ||||||

| 8. Problem drinking | — | |||||||

Notes. Controlling reactions scale refers to the SRQ scale composed of the two subscales we separated: controlling reactions and infantilizing reactions. Thus, the high correlations between this scale and its components are not meaningful and the variables were not included in the same models.

p < .01.

We tested models with both (a) controlling reactions as a single scale (Model 1), and (b) controlling scale split into separate subscales for pure controlling reactions and infantilizing reactions, as supported by our confirmatory factor analysis (Model 2). Both theorized models was tested with social reactions as exogenous variables, perceived control, PTSD, and drinking to cope as a chain of intervening variables, and problem drinking as the outcome. For Model 1 (i.e., controlling/ infantilizing as a single scale), we started with a saturated model to test the mediation hypotheses separately, allowing for the predictors to correlate (see Table 2 for standardized direct and indirect effects, noting that significant indirect effects are illustrated by confidence intervals that do not include 0). Based on the model results, we proceeded to test a subsequent model with all non-significant direct paths deleted where the indirect effects were significant. Thus, we deleted direct paths from controlling reactions to drinking to cope and problem drinking, as well as direct paths from perceived control to problem drinking. The final Model 1 had acceptable fit, considering that the χ2 test is likely to be significant for large samples regardless of goodness-of-fit: χ2 (5, N=1863) = 14.61, p < .05; RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .02, CFI = .99, TLI = .98.

Table 2.

Direct and indirect standardized effects of predictors on problem drinking in the saturated model.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Variable | Indirect | 95% CI | Direct | Total | Indirect | 95% CI | Direct | Total |

| Controlling reactions scale |

.09 | [.05, .12]* | .05 | .14* | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Controlling reactions subscale |

-- | -- | -- | -- | .02 | [−.04, .09] | .01 | .03 |

| Infantilizing reactions subscale |

-- | -- | -- | -- | .06 | [.03, .09]* | .04 | .11* |

| Tangible support scale |

.01 | [−.03, .04] | .04 | .05 | .01 | [−.02, .05] | .05 | .06 |

| Perceived control |

−.08 | [−.11, −.05]* | −.001 | −.08* | −.08 | [−.11, −.05]* | .00 | −.08* |

| PTSD | .17 | [.13, .24]* | .01 | .18* | .17 | [.14, .21]* | .01 | .19* |

| Drinking to cope |

-- | -- | .52 | .52* | -- | .52 | .52* | |

Controlling reactions scale refers to the SRQ scale that includes both controlling and infantilizing reactions. Controlling reactions subscale refers to the subscale used in the second model where we separated infantilizing from purely controlling reactions to assess their differential predictive effects on PTSD and problem drinking.

p < .01.

As we predicted, tangible support and controlling reactions had different effects on perceived control and PTSD symptoms in Model 1. Tangible support was positively related, whereas controlling reactions was negatively related, to perceived control. In addition, the relation between tangible support and PTSD was much weaker than the relation between controlling reactions and PTSD, yet it was not negative (i.e., tangible support does not act as a protective factor against PTSD). In turn, perceived control negatively predicted PTSD symptoms and drinking to cope. As expected, PTSD symptoms were positively related to drinking to cope, and, drinking to cope predicted greater problem drinking.

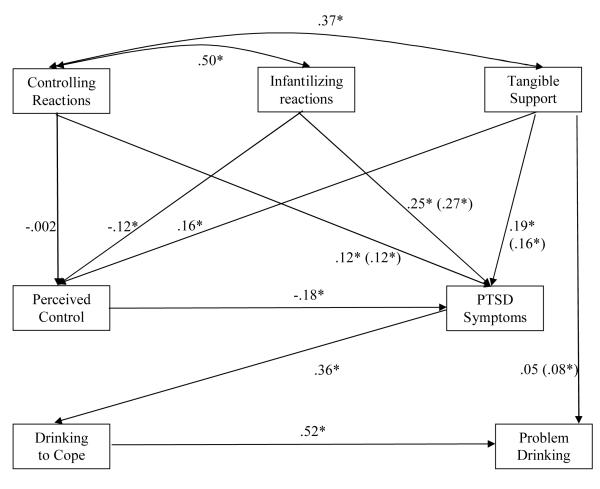

To further investigate the separate effects of infantilizing and controlling reactions, we included both subscales (and the tangible support scale) as predictors in Model 2. As before, we included perceived control over recovery, PTSD, and drinking to cope as mediators, and problem drinking as the outcome. Again we started with a saturated model (see Table 2 for standardized coefficients) and deleted non-significant direct paths for the final model. The final Model 2 had good fit (slightly better than Model 1): χ2 (7, N=1863) = 17.56, p < .05; RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .02, CFI = .99, TLI = .98. More importantly, the model revealed that, as we hypothesized, infantilizing reactions, but not controlling reactions, negatively predicted perceived control over recovery, suggesting that these infantilizing reactions might be driving the negative effects in other studies as well. Both reactions also directly predicted PTSD symptoms, although infantilizing reactions had a stronger effect than controlling reactions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Final Model of Social Reactions, Perceived Control, PTSD, and Problem Drinking in Sexual Assault Survivors. Numbers represent standardized coefficients of direct effects. Where appropriate total effects are noted in parentheses (e.g., the direct effect of tangible effect on PTSD is .19, the total effect is .16).

Discussion

The present study tested a theoretically-based model of multiple mediators of the relationships between social reactions to sexual assault and problem drinking symptoms in adult victims recruited from the community. Overall, we found support for our predictions that controlling social reactions are positively related to PTSD and problem drinking, and that perceived control over recovery partially mediates this effect. We did not find, however, tangible support to be a protective factor against PTSD and problem drinking, which is unfortunately in line with previous research that found small or even positive relationships. We were primarily interested in the role of perceived control, and found that (a) positive reactions are related to more perceived control, (b) negative reactions are related to less perceived control, and (c) perceived control is a protective factor against not only PTSD, but also problem drinking. The negative relation between perceived control and problem drinking was fully mediated by PTSD and drinking to cope. These results suggest that women’s beliefs that they can recover after the assault, and that they are in control of this process, may help them recover better and experience fewer symptoms, which in turn reduces their need to drink to cope with distress, and hence their likelihood of problem drinking. These findings extend past research about the protective effects of perceived control on PTSD (Frazier, 2003) to the outcome of problem drinking in sexual assault victims. We must, however, note that the effects were rather small in our sample, most likely because of the complexity of factors related to problem drinking and the large role played by assault characteristics. These results are important, however, because they uncover the relation of social reactions with psychological mediators that can, at least in theory, be responsive to interventions, and are informative to mental health and law enforcement professionals who work with victims and their informal social network members. Self-efficacy training to increase women’s feelings of control over their lives and decisions could prove beneficial for reducing comorbid PTSD and drinking problems common in sexual assault victims. Training and informing potential support providers about the benefits of providing support without infantilizing or controlling victims, as well as teaching them specific response skills, could also prove helpful for long-term recovery. This is particularly true for first responders (e.g., law enforcement personnel, nurses, crisis counselors), as their reactions could set the tone for subsequent responses.

The present study also offers an empirical test of the differential effects of various types of social reactions on psychosocial mediators and drinking that goes beyond the positive/ negative reactions dichotomy. Although it is important to distinguish between the effects of positive and negative reactions, it is also helpful to understand that the effects of these reactions are not clear-cut and depend on victims’ perceptions. Tangible support had a significant positive effect on perceived control, suggesting that others’ tangible support makes victims feel more empowered to cope with their problems and more in control of their own recovery. In contrast, controlling reactions had a negative effect. A further distinction between purely controlling reactions and infantilizing reactions uncovered their differential effects on perceived control and on PTSD and problem drinking. In line with Campbell and colleagues (2001), we found that purely controlling reactions did not have a significant effect on other variables, perhaps because, as Ahrens and colleagues (2009) suggest, women’s perceptions of these types of reactions vary widely and depend on the support provider’s relationship to the victim.

Thus, the effect of the SRQ controlling reactions scale was in fact mostly driven by infantilizing reactions, which were found to be harmful by Ahrens and colleagues regardless of support provider identity. It makes theoretical sense that treating the victim as if she were incapable of caring for herself, or in some way incompetent, would reduce her belief in her ability to cope with the assault and control her recovery, which in turn relates to reduced ability to heal, and perhaps increased reliance on drinking to cope and hence increased problem drinking.

Our study had a number of limitations. Although the sample size was suitably large for the demands of structural equation modeling, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the cross-sectional design and nonrepresentative sample of the study. Like all structural equation modeling, these analyses are limited by the fact that a model with good fit does not mean that the model is correct (Kline, 1998). The model was developed based on past theory and empirical research in this area, however, and longitudinal data being collected from this sample may also help clarify the direction of effects.

Although our sample was large and diverse, we are nevertheless aware of the limitations of relying on a self-selected sample to generalize to a population. During recruitment, we actively pursued diversity by posting fliers around many different neighborhoods, both throughout the city and in the suburban areas, and at colleges and universities. We also targeted cultural centers in an effort to reach underrepresented minorities. We posted our weekly ads both online and in print for an entire year to ensure that women of all ages and backgrounds had access to the information. Despite our efforts, it is possible that our volunteers are women who are more likely to be motivated by the compensation and more prepared to share their experiences. In fact, our sample was overall of low socio-economic status and lower income. In addition, some of our participants had experienced the assault a long time before the survey (on average, 14 years before) and had likely reached a point where they could open up about their experiences. We are, however, confident that even social reactions that happened a long time before could affect the recovery process by setting the tone for further social reactions and the victims’ perceptions of control over recovery, which can further impact their coping abilities, life choices, and psychological well-being over the years. The significant effects of social reactions on assault-related PTSD are especially meaningful if these reactions happened a long time ago, because they showcase how pervasive and long-lasting they can be. Finally, in the present study we were not able to disentangle reactions given by specific providers, because participants evaluated each social reaction globally, across various providers. In future studies, we will examine a subsample of women who only told one or two support providers, which should allow for comparisons between the effects of tangible support and controlling/ infantilizing reactions as a function of support provider relationship to the victim.

Our study also had a number of strengths. The model tested here is more comprehensive than past models tested in the literature on the link between social reactions and problem drinking and is theoretically-grounded. This and other possible models should be evaluated with longitudinal data in sexual assault survivors from a variety of sample sources (e.g., college, treatment, community), so that mediational pathways can be evaluated and appropriate inferences can be drawn for treatment and intervention with various subgroups. Such models can provide empirical knowledge that informs clinical treatment with victims, and intervention and educational efforts with both informal and formal support sources.

The current findings suggest that enhancing perceived control over recovery may be important for reducing PTSD and problem drinking symptoms in treatment and intervention with sexual assault victims. The results also suggest that educational efforts with those responding to survivors should explain that although responses of tangible support to survivors may be related to greater PTSD (presumably because more distressed victims seek more help); they may be helpful in enhancing survivors’ perceived control over recovery, which is related to fewer PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, certain controlling responses may be harmful, such as those that infantilize survivors, because they can reinforce the loss of control survivors experienced during the assault. Teaching informal social network members and formal support providers the helpful and unhelpful effects of different reactions to assault disclosure may enhance their ability to respond supportively in ways that enhance survivors’ recovery process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AA 17429 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Dr. Sarah Ullman. We thank Cynthia Najdowski, Mark Relyea, Amanda Vasquez, Meghna Bhat, Saloni Shah, Susan Zimmerman, Rene Bayley, Farnaz Mohammad-Ali, & Gabriela Lopez for assistance with data collection.

References

- Ahrens C, Campbell R, Ternier-Thames K, Wasco S, Sefl T. Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of sexual assault survivors’ first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens C, Cabral G, Abeling S. Healing or hurtful: Sexual assault survivors’ interpretations of social reactions from support providers. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for PTSD in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Wasco SM, Barnes HE. Social reactions to rape victims: Healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence & Victims. 2001;16:287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowy DO, Garvin BJ. Social support, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations: Impact of self-care behaviors and glycemic control in Caucasian and African American adults with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2006;32:777–786. doi: 10.1177/0145721706291760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:203–211. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. PTSD as a mediator between childhood rape and alcohol use in adult women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipas H, Ullman S. Social reactions to sexual assault victims from various support sources. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:673–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale manual. National Computer Systems; Minneapolis: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA. Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1257–1269. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Keenan N, Anders S, Perera S, Shallcross S, Hintz S. Perceived past, present, and future control and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:745–765. doi: 10.1037/a0022405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Mortensen H, Steward J. Coping strategies as mediators of the relations among perceived control and distress in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Steward J, Mortensen H. Perceived control and adjustment to trauma: A comparison across events. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson C, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators of child sexual abuse and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Edmunds CN, Seymour AK. Rape in America: A report to the nation. National Victim Center; Arlington, VA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H. The impact of social support and negative disclosure reactions on sexual assault victims: A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2010;11:210–227. doi: 10.1080/15299730903502946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Breitkopf CR. Coping with the experience of rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. PTSD symptoms and self-rated recovery among adult sexual assault survivors: The effects of traumatic life events and psychosocial variables. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of PTSD and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relyea M, Ullman SE. Exploring the Complexity of Negative Reactions in the Social Reactions Questionnaire. 2012. Manuscript in Preparation.

- Resnick HS, Holmes MM, Kilpatrick DG, Clum G, Acierno R, Best CL, et al. Predictors of post-rape medical care in a national sample of women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:214–219. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzynski L, Ullman S, Filipas H, Townsend S. Correlates of women’s sexual assault disclosure to informal and formal support sources. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:417–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Israeli A. Substance abuse and co-occurring psychiatric disorders in victims of intimate violence. In: Wekerle C, Hall A-M, editors. The violence and addiction equation: Theoretical and clinical issues in substance abuse and relationship violence. Brunner-Routledge; New York: 2002. pp. 98–122. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ. Direct, indirect, and moderating effects of social support on psychological distress and associated conditions. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial stress: Trends in theory and research. Academic; New York: 1983. pp. 105–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996b;20:505–526. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Psychometric characteristics of the Social Reactions Questionnaire: A measure of reactions to sexual assault victims. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24:257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Talking about sexual assault: Society’s response to survivors. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Predictors of PTSD symptom severity and social reactions in sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:369–389. doi: 10.1023/A:1011125220522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski L. Correlates of PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski L. Psychosocial correlates of PTSD symptom severity in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007a;20:821–831. doi: 10.1002/jts.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Starzynski LL, Long S, Mason G, Long LM. Sexual assault disclosure, social reactions, and problem drinking in women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1235–1257. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, Starzynski LL. Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007b;31:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women’s substance abuse: National survey findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]