Adding cetuximab to chemotherapy improved survival in patients with recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Although HPV and p16 statuses have prognostic value, the observed survival benefit conferred by cetuximab is independent of both. This pattern remained in a combined analysis of both p16 and HPV and in patients with oropharyngeal cancer separately.

Keywords: cetuximab, human papillomavirus, p16, recurrent and metastatic, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck

Abstract

Background

Tumor human papillomavirus (HPV) status is an important prognostic factor in locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). Prognostic value in recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) disease remains to be confirmed. This retrospective analysis of the EXTREME trial, comparing chemotherapy plus cetuximab with chemotherapy first line in R/M SCCHN, investigated efficacy and prognosis according to tumor p16 and HPV status.

Patients and methods

Paired tissue samples were used: p16INK4A expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry, and HPV status determined in extracted DNA samples using oligonucleotide hybridization assays.

Results

Altogether, 416 of 442 patients had tumor samples available for p16 and HPV: 10% of tumors were p16 positive and 5% were HPV positive. Adding cetuximab to chemotherapy improved survival, irrespective of tumor p16 or HPV status. This pattern remained in a combined analysis of p16 and HPV. p16 positivity and HPV positivity were associated with prolonged survival compared with p16 negativity and HPV negativity. Subgroup analysis of patients with oropharyngeal cancer demonstrated a similar pattern to all evaluable patients.

Conclusion

The results from this analysis suggest that p16 and HPV status have prognostic value in R/M SCCHN and survival benefits of chemotherapy plus cetuximab over chemotherapy alone are independent of tumor p16 and HPV status.

introduction

There has been strong support for a causal role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in a subset of patients with oropharynx cancer [1]. Although the incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal carcinomas has increased over the last decade [2], the prevalence of HPV in nonoropharyngeal sites is lower. Tumor HPV status has been established as an important prognostic factor in the locoregionally advanced setting [3]. Also, the presence of HPV in non-oropharyngeal sites has not yet been clearly established to be associated with pathogenesis and outcome [4].

The impact of tumor HPV status on outcome in recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) remains to be clarified. The fact that HPV positivity is an indicator of good prognosis in the curative setting of oropharyngeal cancer indicates that in the R/M setting the vast majority of patients bear HPV-negative tumors. To our knowledge, the influence of tumor HPV status on outcome in R/M SCCHN has been looked at in only one prospectively defined analysis of a large patient population in the phase III SPECTRUM trial investigating an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeting monoclonal antibody (panitumumab) in the first-line setting [5].

Weinberg et al. demonstrated that p16 (CDKN2A) expression is a useful surrogate marker for tumor HPV status in oropharyngeal cancer, and these results were validated in the retrospective analysis of RTOG0129 [3, 6]. p16 status was used as a surrogate marker for HPV in the SPECTRUM analysis [5, 7].

The phase III EXTREME trial reported that the addition of cetuximab to platinum/5-FU significantly improved overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and response compared with platinum/5-FU in the first-line treatment of patients with R/M SCCHN [8]. In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the EXTREME trial to investigate outcome according to tumor HPV and p16 status.

patients and methods

patients

The details of the EXTREME study have previously been reported [8] and they are briefly presented in the supplement.

samples

FFPE tissue samples from paired hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and isotype control stains applied as negative control for EGFR immunohistochemistry (IHC) with the Dako pharmDx EGFR kit were used for p16 IHC and HPV assays, respectively.

IHC

IHC on de-stained H&E tumor samples was carried out using the CINtec® p16INK4A assay, according to the manufacturer's instructions (CINtec® Histology Kit, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, Arizona, USA). Slides were scored manually, from 0 to 3+ for overall cytoplasm and nuclear staining, by a board-certified pathologist. p16 expression was considered p16 positive if >70% of tumor cells showed moderate or strong and diffuse nuclear staining (regardless of cytoplasmic staining intensity); low-intensity staining (0 or 1+) was classified as p16 negative; and heterogeneous moderate- to high-intensity staining (2+ or 3+ both cytoplasmic and nuclear) was considered inconclusive.

HPV assay

Tumor samples with ≥10% tumor nuclei on the matched H&E slides were tested for the presence of HPV. DNA was extracted from isotype control stains applied as negative control for EGFR IHC with the Dako pharmDx EGFR kit and HPV DNA was detected using the FDA approved Cervista® HPV 16/18 and Cervista® HPV HR assays, the latter comprising HPV assay panels 1, 2 and 3 (Hologic Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). Further details are provided in the supplement.

statistics

This was a retrospective analysis. Data from the primary analysis were used (clinical cut-off 12 March 2007). The primary endpoint was OS and secondary endpoints were PFS and response.

Analyses were conducted on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and on the subgroup of patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma. Further details are provided in the supplement.

results

samples and baseline characteristics

There were 442 patients in the ITT population and tumor samples from 416 (94.1%) were available for p16 and HPV assessment.

Of 416 samples tested for p16: 41 (10%) were p16 positive, 340 (82%) were p16 negative, and 35 (8%) were inconclusive. Of the 41 p16-positive samples, 34 were HPV evaluable with 19 HPV positive (56%) and 15 HPV negative (44%); 7 failed the HPV test for internal control due to insufficient DNA.

Of 416 samples tested for HPV: 24 (6%) were HPV positive (22 for HPV-16 and 2 for other subtypes of HPV), 297 (71%) were HPV negative, and 70 (17%) were HPV inconclusive. In 25 (6%) samples, the assay failed. Of the 24 HPV-positive samples, 22 were p16 evaluable with 19 (86%) positive and 3 (14%) negative using p16 IHC testing; 2 (9%) were inconclusive. HPV detection and p16 IHC data are summarized in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Patient and disease characteristics at baseline in the ITT population and in the p16-positive/p16-negative and HPV-positive/HPV-negative subgroups were broadly similar (Table 1) with some exceptions, including: the proportion of patients with metastatic (including recurrent) disease was higher in the HPV-positive population than within the HPV-negative population; the proportion of p16-positive and HPV-positive tumors was higher among oropharyngeal tumors compared with other primary tumor sites.

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics at baseline and platinum regimen received in the ITT, p16 and HPV evaluable populations

| Characteristics, n (%) | ITT (n = 442) |

p16+ (n = 41) |

p16− (n = 340) |

HPV+ (n = 24) |

HPV− (n = 297) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT + cetuximab (n = 222) | CT (n = 220) | CT + cetuximab (n = 18) | CT (n = 23) | CT + cetuximab (n = 178) | CT (n = 162) | CT + cetuximab (n = 11) | CT (n = 13) | CT + cetuximab (n = 145) | CT (n = 152) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 197 (89) | 202 (92) | 16 (89) | 19 (83) | 157 (88) | 151 (93) | 9 (82) | 12 (92) | 129 (89) | 142 (93) |

| Female | 25 (11) | 18 (8) | 2 (11) | 4 (17) | 21 (12) | 11 (7) | 2 (18) | 1 (8) | 16 (11) | 10 (7) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| <65 | 183 (82) | 182 (83) | 15 (83) | 22 (96) | 146 (82) | 132 (81) | 9 (82) | 12 (92) | 120 (83) | 127 (84) |

| ≥65 | 39 (18) | 38 (17) | 3 (17) | 1 (4) | 32 (18) | 30 (19) | 2 (18) | 1 (8) | 25 (17) | 25 (16) |

| Karnofsky performance status | ||||||||||

| <80 | 27 (12) | 25 (11) | 3 (17) | 1 (4) | 22 (12) | 23 (14) | 3 (27) | 1 (8) | 15 (10) | 19 (13) |

| ≥80 | 195 (88) | 195 (89) | 15 (83) | 22 (96) | 156 (88) | 139 (86) | 8 (73) | 12 (92) | 130 (90) | 133 (88) |

| Histology | ||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 35 (16) | 40 (18) | 1 (6) | 3 (13) | 30 (17) | 29 (18) | 0 | 1 (8) | 25 (17) | 28 (18) |

| Moderately differentiated | 93 (42) | 101 (46) | 8 (44) | 12 (52) | 72 (40) | 76 (47) | 4 (36) | 7 (54) | 61 (42) | 70 (46) |

| Poorly differentiated | 46 (21) | 46 (21) | 6 (33) | 5 (22) | 38 (21) | 32 (20) | 5 (45) | 3 (23) | 32 (22) | 34 (22) |

| NOS/missing | 48 (22) | 33 (15) | 3 (17) | 3 (13) | 38 (21) | 25 (15) | 2 (18) | 2 (15) | 27 (19) | 20 (13) |

| Primary tumor site | ||||||||||

| Oropharynx | 80 (36) | 69 (31) | 8 (44) | 16 (70) | 65 (37) | 47 (29) | 8 (73) | 10 (77) | 48 (33) | 44 (29) |

| Hypopharynx | 28 (13) | 34 (15) | 4 (22) | 2 (9) | 21 (12) | 26 (16) | 1 (9) | 0 | 18 (12) | 26 (17) |

| Larynx | 59 (27) | 52 (24) | 3 (17) | 2 (9) | 48 (27) | 39 (24) | 0 | 1 (8) | 45 (31) | 31 (20) |

| Oral cavity | 46 (21) | 42 (19) | 3 (17) | 1 (4) | 37 (21) | 32 (20) | 2 (18) | 2 (15) | 28 (19) | 30 (20) |

| Othera | 9 (4) | 23 (10) | 0 | 2 (9) | 7 (4) | 18 (11) | 0 | 0 | 6 (4) | 21 (14) |

| Extent of disease | ||||||||||

| Recurrent only | 118 (53) | 118 (54) | 6 (33) | 12 (52) | 99 (56) | 90 (56) | 4 (36) | 1 (8) | 80 (55) | 88 (58) |

| Metastatic, including recurrent | 104 (47) | 102 (46) | 12 (67) | 11 (48) | 79 (44) | 72 (44) | 7 (64) | 12 (92) | 65 (45) | 64 (42) |

| Platinum regimen | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin | 69 (31) | 80 (36) | 5 (28) | 9 (39) | 59 (33) | 59 (36) | 4 (36) | 3 (23) | 42 (29) | 57 (38) |

| Cisplatin | 149 (67) | 135 (61) | 13 (72) | 13 (57) | 116 (65) | 100 (62) | 7 (64) | 10 (77) | 103 (71) | 94 (62) |

| Missing | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 0 | 1 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

aParanasal sinuses and non-classifiable sites.

CT, chemotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; ITT, intention-to-treat; NOS, none otherwise specified.

treatment effect

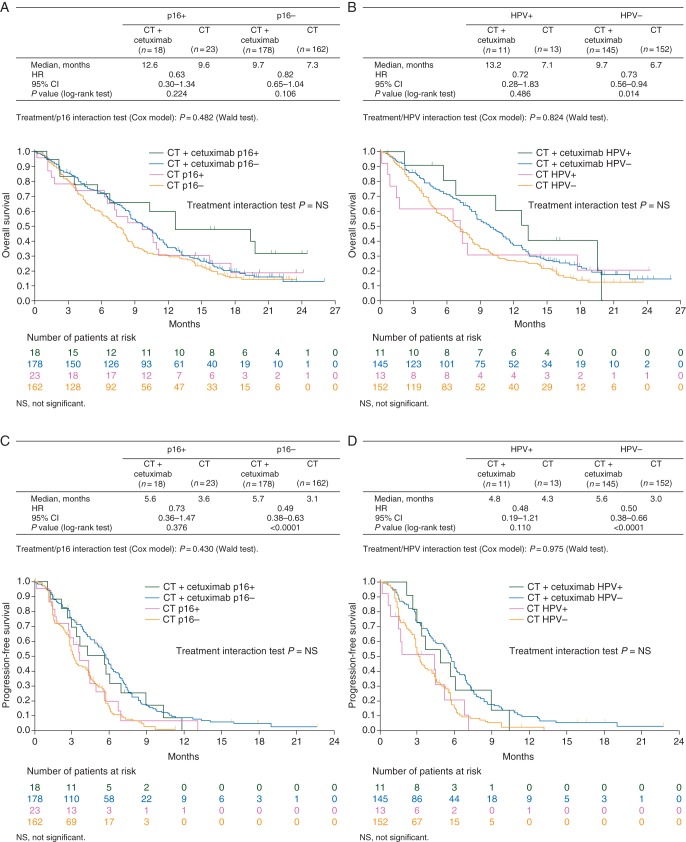

For OS, HRs in favor of chemotherapy plus cetuximab were seen within p16-positive, p16-negative, HPV-positive and HPV-negative subgroups (Figure 1A and B). HRs in favor of chemotherapy plus cetuximab were also seen for PFS within all subgroups (Figure 1C and D). Interaction tests for OS and PFS suggested that the treatment effect of chemotherapy plus cetuximab versus chemotherapy was independent of tumor p16 expression or HPV status (no significant interaction was noted).

Figure 1.

(A) Overall survival according to treatment arm and tumor p16 expression. (B) Overall survival according to treatment arm and tumor HPV status. (C) Progression-free survival according to treatment arm and tumor p16 expression. (D) Progression-free survival according to treatment arm and tumor HPV status.

The addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy improved the chances of achieving a response across all p16 and HPV subgroups, although this result is limited by the low number of patients (Table 2). A combined p16/HPV OS analysis demonstrated similar findings to those obtained with the individual biomarkers and supported the benefits of chemotherapy plus cetuximab over chemotherapy alone across all subgroups, although the numbers were generally too small to allow conclusions to be drawn (Table 3).

Table 2.

Response rate between arms according to tumor p16 expression and tumor HPV status: treatment effect

| Parameters | p16+ |

p16− |

HPV+ |

HPV− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT + cetuximab (n = 18) | CT (n = 23) | CT + cetuximab (n = 178) | CT (n = 162) | CT + cetuximab (n = 11) | CT (n = 13) | CT + cetuximab (n = 145) | CT (n = 152) | |

| Response rate, n (%) | 9 (50) | 5 (22) | 65 (37) | 28 (17) | 7 (64) | 1 (8) | 49 (34) | 31 (20) |

| P value (CMH test) | 0.061 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.009 | ||||

| Odds ratio | 3.60 | 2.75 | 21.00 | 1.99 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.93–13.95 | 1.66–4.58 | 1.94–227.21 | 1.18–3.63 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; CMH, Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel; CT, chemotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Table 3.

Overall survival according to combined tumor p16 expression and HPV status: treatment effect

| Parameters | HPV+/p16+ |

HPV+/p16− |

HPV−/p16+ |

HPV−/p16− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT + cetuximab (n = 10) | CT (n = 9) | CT + cetuximab (n = 1) | CT (n = 2) | CT + cetuximab (n = 5) | CT (n = 10) | CT + cetuximab (n = 134) | CT (n = 132) | |

| Overall survival time | ||||||||

| Median, months | 12.6 | 7.1 | NA | NA | 12.6 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 6.7 |

| P (log-rank test) | 0.552 | NA | 0.613 | 0.025 | ||||

| 95% CI | 6.7–19.8 | 1.7–17.6 | NA | NA | 1.0– | 6.2–15.7 | 8.5–11.0 | 5.0–7.9 |

CI, confidence interval; CT, chemotherapy; NA, not applicable; HPV, human papillomavirus.

prognostic effect

For all patients in the p16- and HPV-evaluable populations, within treatment arms, survival was generally longer in patients with p16-positive or HPV-positive disease compared with those with p16-negative or HPV-negative disease (Table 4). Of the 149 (34%) patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma in the ITT population, 136 (91%) had p16-evaluable tumors and 110 (74%) had HPV-evaluable tumors. The pattern of efficacy within treatment arms in these subpopulations was similar to that observed in the overall p16- and HPV-evaluable population. However, at least within the chemotherapy plus cetuximab arm, the effect was more pronounced (Table 5). Although there were trends in both subpopulations, these trends were not observed for all efficacy endpoints.

Table 4.

Impact of tumor p16 expression and HPV status on efficacy within treatment arms in the p16- and HPV-evaluable populations: prognostic effect

| Parameters | CT + cetuximab |

CT |

CT + cetuximab |

CT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16+ (n = 18) | p16− (n = 178) | p16+ (n = 23) | p16− (n = 162) | HPV+ (n = 11) | HPV− (n = 145) | HPV+ (n = 13) | HPV− (n = 152) | |

| Overall survival | ||||||||

| Median, months | 12.6 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 13.2 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 6.7 |

| P value (log-rank test) | 0.092 | 0.449 | 0.531 | 0.811 | ||||

| HR | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.92 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.32–1.10 | 0.50–1.36 | 0.39–1.63 | 0.48–1.77 | ||||

| Progression-free survival | ||||||||

| Median, months | 5.6 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 3.0 |

| P value (log-rank test) | 0.562 | 0.587 | 0.617 | 0.732 | ||||

| HR | 1.17 | 0.87 | 1.18 | 1.12 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.69–2.01 | 0.53–1.43 | 0.62–2.27 | 0.60–2.08 | ||||

| Response rate, n (%) | 9 (50) | 65 (37) | 5 (22) | 28 (17) | 7 (64) | 49 (34) | 1 (8) | 31 (20) |

| P value (CMH test) | 0.262 | 0.602 | 0.047 | 0.267 | ||||

| Odds ratio | 1.74 | 1.33 | 3.43 | 0.33 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.66–4.60 | 0.46–3.88 | 0.96–12.28 | 0.04–2.60 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; CMH, Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel; CT, chemotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 5.

Impact of tumor p16 expression and HPV status on efficacy within treatment arms in patients with oropharyngeal tumors: prognostic effect

| Parameters | CT + cetuximab |

CT |

CT + cetuximab |

CT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16+ (n = 8) | p16− (n = 65) | p16+ (n = 16) | p16− (n = 47) | HPV+ (n = 8) | HPV− (n = 48) | HPV+ (n = 10) | HPV− (n = 44) | |

| Overall survival | ||||||||

| Median, months | 19.4 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 19.4 | 10.9 | 7.2 | 7.3 |

| P value (log-rank test) | 0.069 | 0.426 | 0.375 | 0.821 | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.40 (0.14–1.12) | 0.76 (0.39–1.50) | 0.65 (0.25–1.69) | 1.09 (0.50–2.37) | ||||

| Progression-free survival | ||||||||

| Median, months | 7.5 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 2.9 |

| P value (log-rank test) | 0.557 | 0.949 | 0.809 | 0.476 | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.36–1.75) | 0.98 (0.50–1.91) | 1.11 (0.49–2.52) | 1.34 (0.60–2.97) | ||||

| Response rate, n (%) | 6 (75) | 15 (32) | 2 (13) | 10 (21) | 6 (75) | 15 (31) | 0 (0) | 11 (25) |

| P value (CMH test) | 0.019 | 0.443 | 0.019 | 0.079 | ||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 6.29 (1.17–33.82) | 0.53 (0.10–2.72) | 6.60 (1.19–36.59) | <0.0010 (–) | ||||

CI, confidence interval; CMH, Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel; CT, chemotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, hazard ratio.

safety

The incidences of adverse events (AEs) listed according to biomarker subgroup and treatment received are shown in Table 6. The AE incidences were similar across the subgroups and the difference between the treatment arms comparable with those observed in the whole ITT population. The incidence of treatment-related AEs leading to death was similar in the p16-negative and HPV-negative subgroups and in the p16-positive and HPV-positive subgroups. Only one of these events in each of the p16- and HPV-evaluable subgroups in the chemotherapy plus cetuximab arm was considered to be cetuximab related.

Table 6.

Adverse events: per treatment as received*

| Categories | ITT |

p16+ |

p16− |

HPV+ |

HPV− |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT + cetuximab (n = 219) | CT (n = 215) | CT + cetuximab (n = 18) | CT (n = 22) | CT + cetuximab (n = 175) | CT (n = 159) | CT + cetuximab (n = 11) | CT (n = 13) | CT + cetuximab (n = 145) | CT (n = 151) | |

| Any adverse event | 218 (99.5) | 208 (97) | 18 (100) | 20 (91) | 174 (99) | 155 (98) | 11 (100) | 13 (100) | 145 (100) | 145 (96) |

| Treatment-related | 217 (99) | 195 (91) | 18 (100) | 18 (82) | 173 (99) | 144 (91) | 11 (100) | 11 (85) | 144 (99) | 136 (90) |

| Any SAE | 110 (50) | 102 (47) | 10 (56) | 12 (55) | 86 (49) | 75 (47) | 4 (36) | 5 (39) | 72 (50) | 72 (48) |

| Treatment-related | 64 (29) | 58 (27) | 6 (33) | 7 (32) | 52 (30) | 44 (28) | 2 (18) | 2 (15) | 47 (32) | 41 (27) |

| Cetuximab-related | 23 (11) | N/A | 3 (17) | N/A | 18 (10) | N/A | 1 (9) | N/A | 17 (12) | N/A |

| Grade 3/4 adverse events | 179 (82) | 164 (76) | 16 (89) | 17 (77) | 140 (80) | 123 (77) | 11 (100) | 11 (85) | 117 (81) | 115 (76) |

| Treatment-related | 150 (68) | 125 (58) | 15 (83) | 12 (55) | 118 (67) | 95 (60) | 11 (100) | 7 (54) | 98 (68) | 92 (61) |

| Adverse events leading to death | 34 (16) | 33 (15) | 3 (17) | 4 (18) | 24 (14) | 23 (15) | 2 (18) | 3 (23) | 21 (15) | 25 (17) |

| Treatment-related | 7 (3) | 12 (6) | 0 | 1 (5) | 5 (3) | 9 (6) | 0 | 1 (8) | 5 (3) | 9 (6) |

| Cetuximab-related | 1 (0.5) | N/A | 0 | N/A | 1 (1) | N/A | 0 | N/A | 1 (1) | N/A |

*Data presented in brackets are numbers (%).

CT, chemotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; ITT, intention-to-treat; N/A, not applicable; SAE, serious adverse event.

discussion

The results of this analysis, based on 416 available tumor samples from patients with R/M SCCHN treated first-line in the EXTREME study, indicate that chemotherapy plus cetuximab was associated with survival benefits over chemotherapy alone independent of tumor p16 expression or HPV status. No new safety findings were identified.

The analysis provided indications for the prognostic utility of tumor HPV/p16 status in R/M disease. In analyses of the 2 biomarkers, although the patient numbers are generally small within the individual groups, patients with p16- or HPV-positive tumors tended to have a longer OS time than those with p16- or HPV-negative tumors. One-third of the patients had oropharyngeal cancers, and analysis of this subgroup supported the findings from the individual HPV- and p16-evaluable subpopulations.

The numbers of patients with p16-positive or HPV-positive disease in this analysis are low, 10% of samples being p16 positive and 5% HPV positive. This finding is not unexpected, given that p16/HPV positivity is an indicator of good prognosis in patients with locally advanced disease. The low patient numbers with p16-positive/HPV-positive tumors are the main limitation of this study so that the results should be interpreted with caution and precluding a multivariate analysis.

The results reported here should be discussed in the context of the results from the SPECTRUM trial, in which the combination of 5-FU/platinum and panitumumab first line did not significantly improve OS compared with 5-FU/platinum alone [7]. The demonstration in the current analysis that p16 and HPV are prognostic markers in SCCHN supports the findings from the SPECTRUM trial. However, whereas the data from the EXTREME trial suggest that the efficacy benefits of chemotherapy plus cetuximab over chemotherapy alone are independent of p16/HPV status, the SPECTRUM trial reported efficacy benefits only in the p16-negative population.

A major difference between these two trials is the proportion of evaluable tumor samples that were p16 positive. In the SPECTRUM trial, more than 20% of evaluable samples were p16 positive, compared with 11% in the EXTREME trial. The primary reasons for this difference are probably the timing of the studies and the types of patients enrolled. For example the proportion of head and neck cancers associated with p16/HPV has increased over time [9, 10]: the EXTREME trial was initiated 3 years earlier than the SPECTRUM trial (in 2004 compared with 2007). In addition, the EXTREME trial was carried out exclusively in European centers whereas the SPECTRUM trial enrolled patients from centers around the world, including North and South America and Asia-Pacific, regions in which the incidence of SCCHN associated with HPV is higher than in Europe [11]. Interestingly, around one-third of patients enrolled in the EXTREME trial were from Spain, a country with a <5% incidence of HPV-positive SCCHN at the time of recruitment [12]. Spanish centers did not participate in the SPECTRUM trial.

It is of note that, in the SPECTRUM study, prespecified criteria, which were different from the ones used in our study, of p16 positivity were used and therefore the findings reported may not reflect the actual positivity rate. It should be mentioned that when alternative cutoffs for positivity (between 10% and 70%) were used, a difference in outcome could not be observed [7]. Our findings are in line with the results of the investigation by Mehra et al. [13], which used a p16 assessment similar to the one in the present study, reporting that the patients with HPV-positive or p16-positive tumors had an improved overall response and OS.

It is conceivable that differences in the results from the EXTREME and SPECTRUM trials may also be due in part to the two different EGFR monoclonal antibodies used, namely cetuximab (a chimeric human/murine IgG1 antibody) and panitumumab (a fully human IgG2 EGFR antibody). Although both antibodies have demonstrated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, it is of a different order and by a different mechanism [14–16].

The analyses reported here indicate that p16 may be used as a surrogate marker for initial HPV screening, followed by molecular HPV DNA detection, although p16 was shown not to be a reliable surrogate biomarker of tumor HPV status in non-oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [17]. The results from the detection analyses are supported by the clinical results, which demonstrated that the efficacy findings, in terms of tumor p16 expression and HPV DNA status, were similar. In the combined biomarker analysis carried out for OS, the pattern of efficacy was similar to that seen in the individual biomarker analyses. However, the numbers of patients in all but the HPV-negative/p16-negative subgroup was small, and larger numbers of patients would be required to enable firm conclusions to be drawn. Although a treatment effect association was found only in the p16-negative/HPV-negative subgroups, the same trend could be observed in both of the HPV subgroups. This may be due to the large sample sizes in the HPV-negative subgroup compared with the HPV-positive subgroup.

It should be noted that although the Cervista HPV assays do not have regulatory approval for use outside the setting of the detection of cervical HPV DNA, the assays have been used by others for head and neck tumor material testing [18, 19].

In conclusion, this analysis of the EXTREME trial indicated that the survival benefits of chemotherapy plus cetuximab over chemotherapy alone were independent of tumor p16, HPV or combined p16/HPV status. It also supported findings from the SPECTRUM trial that p16/HPV status is a prognostic factor in R/M SCCHN.

funding

This work was supported by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

disclosure

JBV, AP, FP, LL and RM have advisory board activities with and have given invited lectures for Merck Serono. FB, BdB, and IC are employees of Merck Serono.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families. The authors acknowledge Hans Jürgen Grote (Merck KGaA) for technical/operational support and scientific input to the biomarker analyses, and the contribution of Jo Shrewsbury-Gee (Cancer Communications and Consultancy Ltd, Knutsford, UK), who provided medical writing services on behalf of the authors.

references

- 1.Rampias T, Sasaki C, Weinberger P, et al. E6 and e7 gene silencing and transformed phenotype of human papillomavirus 16-positive oropharyngeal cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:412–423. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehanna H, Beech T, Nicholson T, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer—systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013;35:747–755. doi: 10.1002/hed.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isayeva T, Li Y, Maswahu D, et al. Human papillomavirus in non-oropharyngeal head and neck cancers: a systematic literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S104–S120. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0368-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermorken J, Stöhlmacher J, Oliner K, et al. Safety and efficacy of panitumumab (pmab) in HPV positive (+) and HPV negative (−) recurrent/metastatic (R/M) squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN): analysis of the phase 3 SPECTRUM trial. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl 2):13 LBA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus—associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:736–747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermorken JB, Stohlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:697–710. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, et al. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Licitra L, Zigon G, Gatta G, et al. Human papillomavirus in HNSCC: a European epidemiologic perspective. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:1143–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.10.002. vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, et al. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehra R, Egloff AM, Li S, et al. Analysis of HPV and ERCC1 in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (R/M SCCHN) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) (abstr 6006) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurai J, Chikumi H, Hashimoto K, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by cetuximab against lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1552–1561. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Albaitero A, Ferris RL. Immune activation by epidermal growth factor receptor specific monoclonal antibody therapy for head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:1277–1281. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.12.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider-Merck T, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Berger S, et al. Human IgG2 antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor effectively trigger antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity but, in contrast to IgG1, only by cells of myeloid lineage. J Immunol. 2010;184:512–520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rampias T, Pectasides E, Prasad M, et al. Molecular profile of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas bearing p16 high phenotype. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2124–2131. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo M, Dhillon J, Khanna A, et al. Cervista HPV HR and HPV16/18 assays in head and neck FNA specimens, a valid option of HPV testing, compared with HPV in situ hybridization/p16 immunostaining assays in tissue specimens. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2012;1:S71. (abstr 124) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna A, Patel S, Feng J, et al. Validation of Cervista HPV HR and Cervista HPV16/18 assays in head and neck FNA specimens from patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2012;1:S71. (abstr 125) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.