The BOLERO-2 trial demonstrated that adding everolimus to exemestane substantially improved clinical benefit with acceptable safety in postmenopausal women with HR+ breast cancer relapsing/progressing on a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor. Incidences and severities of everolimus-related toxicity were consistent with other oncology settings, and were manageable using established strategies.

Keywords: advanced breast cancer, everolimus, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), safety

Abstract

Background

In the BOLERO-2 trial, everolimus (EVE), an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, demonstrated significant clinical benefit with an acceptable safety profile when administered with exemestane (EXE) in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive (HR+) advanced breast cancer. We report on the incidence, time course, severity, and resolution of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) as well as incidence of dose modifications during the extended follow-up of this study.

Patients and methods

Patients were randomized (2:1) to receive EVE 10 mg/day or placebo (PBO), with open-label EXE 25 mg/day (n = 724). The primary end point was progression-free survival. Secondary end points included overall survival, objective response rate, and safety. Safety evaluations included recording of AEs, laboratory values, dose interruptions/adjustments, and study drug discontinuations.

Results

The safety population comprised 720 patients (EVE + EXE, 482; PBO + EXE, 238). The median follow-up was 18 months. Class-effect toxicities, including stomatitis, pneumonitis, and hyperglycemia, were generally of mild or moderate severity and occurred relatively early after treatment initiation (except pneumonitis); incidence tapered off thereafter. EVE dose reduction and interruption (360 and 705 events, respectively) required for AE management were independent of patient age. The median duration of dose interruption was 7 days. Discontinuation of both study drugs because of AEs was higher with EVE + EXE (9%) versus PBO + EXE (3%).

Conclusions

Most EVE-associated AEs occur soon after initiation of therapy, are typically of mild or moderate severity, and are generally manageable with dose reduction and interruption. Discontinuation due to toxicity was uncommon. Understanding the time course of class-effect AEs will help inform preventive and monitoring strategies as well as patient education.

Trial registration number

introduction

Non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors (NSAIs) such as anastrozole and letrozole are highly effective therapies for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive (HR+) advanced breast cancer (BC) [1, 2], but disease progression occurs even after initial response [3]. Hyperactivation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) signaling pathway and crosstalk between the mTOR and estrogen receptor pathways are implicated in BC progression and endocrine therapy resistance [4].

Everolimus (EVE; Afinitor®, Novartis) is an oral mTOR inhibitor that enhanced endocrine sensitivity [5] and produced synergistic antiproliferative and apoptotic activity when combined with letrozole [6]. In the randomized, phase 3 BOLERO-2 trial in postmenopausal women with HR+ advanced BC who progressed on/after NSAIs, EVE + exemestane (EXE) significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo (PBO) + EXE [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.43, P < 0.001 by local investigator assessment; HR = 0.36, P < 0.001 by central assessment] [3]. Adverse events (AEs) were consistent with the known safety profile of EVE. These results supported the recent marketing authorization of EVE + EXE in the United States, Europe, and several other countries for treating postmenopausal women with HR+ advanced BC that recurred or progressed on letrozole or anastrozole [7, 8].

Treatment-emergent AEs reported with EVE included stomatitis, rash, diarrhea, fatigue, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, infections, and, less commonly, non-infectious pneumonitis [3, 9–11]. Hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia are of special interest in postmenopausal women with BC who might be at risk for age-related metabolic abnormalities. This report evaluates the safety of EVE + EXE in postmenopausal women in BOLERO-2 based on the median follow-up of 18 months. The incidences of clinically important toxicities associated with EVE, their time course of onset and resolution, as well as the incidences of dose reductions, delays, and discontinuations are described.

methods

eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously described [3] and are presented in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

study design

In this international, multicenter, double-blind study (NCT00863655), patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to EVE (10 mg/day) or matching PBO plus open-label EXE (25 mg/day). Randomization was stratified by documented sensitivity to previous hormonal therapy and the presence of visceral metastasis [3].

The primary end point was PFS; secondary end points included objective response rate, overall survival, and safety. This analysis evaluated safety; results of other end points are presented elsewhere [3, 12, 13].

safety evaluations and dose modifications

Safety assessments included AEs, serious AEs (SAEs), vital signs, and clinical laboratory tests (hematology, serum chemistry, serum lipid profile, and urinalysis) at baseline and every 6 weeks thereafter. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 [14].

For toxicity-related treatment interruptions, the initial dose was to be resumed after the event(s) resolved to grade ≤1 (Table 1) [7]. Exceptions included pneumonitis (grade ≥2), stomatitis (grade ≥3), and any grade 4 toxicity, wherein treatment was resumed at a lower dose. Dose reductions were not required for hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and/or hypertriglyceridemia. EVE dose re-escalation to starting dose was permitted based on safety findings. A maximum of 2 dose-level reductions were allowed (−1 dose level: 5 mg/day; −2 dose levels: 5 mg every other day). Treatment was permanently discontinued in patients requiring reductions beyond 2 dose levels or dose interruptions lasting more than 4 weeks. Patients were followed for onset of new SAEs for 28 days after the last dose.

Table 1.

Everolimus dose modifications for non-hematologic adverse events (excluding metabolic events)

| Severity | Everolimus dose adjustmenta | Management recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | No dose adjustment required | Initiate appropriate medical therapy and monitor |

| Grade 2 |

|

Initiate appropriate medical therapy and monitor |

| Grade 3 |

|

Initiate appropriate medical therapy and monitor |

| Grade 4 | Discontinue EVE | Treat with appropriate medical therapy |

AE, adverse event; EVE, everolimus.

aIf dose reduction is required, the suggested dose is ∼50% lower than the dose previously administered.

bFor non-infectious pneumonitis, everolimus should be reinitiated at a lower dose level (everolimus package insert, 2012).

statistical analysis

The analysis cut-off date was 15 December 2011 (median follow-up, 18 months). The safety population included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment and had ≥1 postbaseline safety evaluation. AEs were summarized using percentages and frequency counts. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate time-to-onset and time-to-resolution of AEs of clinical interest (presented by grouped terms as outlined in supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online). Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

results

patient population

A total of 724 patients were randomized. The safety population comprised 720 patients: 482 in the EVE + EXE arm and 238 in the PBO + EXE arm. The treatment arms were balanced for demographics, disease characteristics, and previous treatment [13]. The median age was 61 years (range, 28–93 years), and most patients were Caucasian (75%) or Asian (20%).

patient disposition and exposure

In the safety population, the median duration of treatment exposure was longer in the EVE + EXE arm than in the PBO + EXE arm at 23.9 and 29.5 weeks for EVE and EXE, respectively, versus 13.4 and 14.1 weeks for PBO and EXE, respectively. The median dose intensity was 8.6 mg/day for EVE (details are presented in supplementary materials, available at Annals of Oncology online).

overall AE profile

AEs were experienced by all patients in the EVE + EXE arm and by 91% in the PBO + EXE arm (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [13]. The most frequently reported all-grade AEs (in at least one-third of patients) in the EVE + EXE arm included stomatitis, rash, fatigue, and diarrhea. Most events were grade 1 or 2. The most common grade 3 or 4 AEs in the EVE + EXE arm were stomatitis, anemia, and hyperglycemia. Non-infectious pneumonitis occurred only in patients receiving EVE + EXE; most events were low grade, with 3% grade 3 and <1% grade 4 events. Hot flushes were reported at a lower frequency in the EVE + EXE arm (5.6%) than in the PBO + EXE arm (14.3%). These findings are consistent with those from the other two EVE BC trials [15, 16].

frequency and time course of AEs of interest

stomatitis

The frequency of all-grade stomatitis and related events was higher in the EVE + EXE arm than in the PBO + EXE arm (67% versus 12%, respectively). Grade 3 events occurred in 8% and <1% of patients, respectively; no grade 4 events were observed.

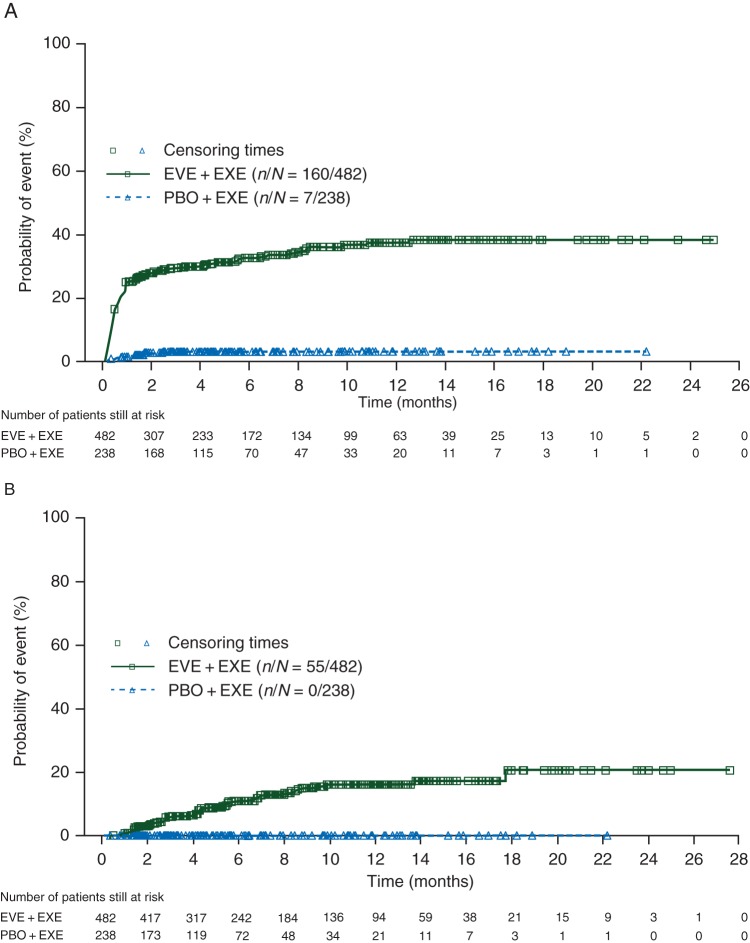

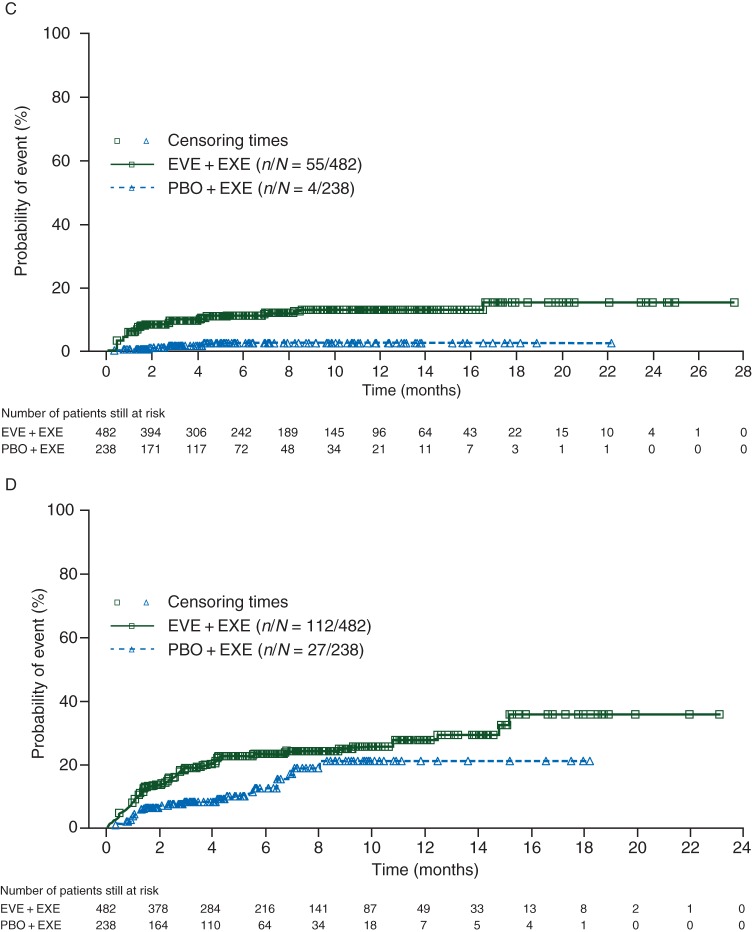

In the EVE + EXE arm, more than one-third of all stomatitis events (grade ≥2) were reported in the first 2 weeks (cumulative risk, 14%). The cumulative risks of stomatitis at 6 and 48 weeks were 26% and 37%, respectively, for EVE + EXE versus 3% for PBO + EXE (Figure 1A). Among 39 patients with grade ≥3 stomatitis in the EVE + EXE arm, 97% experienced resolution to grade ≤1 following dose interruption/reduction after a median of 3.1 weeks (Table 2), and 82% had complete resolution after a median of 7.4 weeks. In the PBO + EXE arm, the median time to resolution from grade 3 to grade ≤1 was 2.6 weeks (time to complete resolution was not assessable; one of two patients had complete resolution).

Figure 1.

Cumulative risk estimates for initial onset of grade ≥2 (A) stomatitis, (B) pneumonitis, (C) hyperglycemia/new-onset diabetes mellitus, and (D) fatigue. EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; PBO, placebo.

Table 2.

Time to adverse event resolution from grade 3/4 to grade ≤1

| Adverse event | EVE + EXE (n = 482) | PBO + EXE (n = 238) |

|---|---|---|

| Stomatitis and related events | n = 39 | n = 2 |

| Proportion resolveda | 97% | 100% |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | 3.1 (1.9–5.3) | 2.6 (1.0–4.1) |

| Fatigue | n = 32 | n = 4 |

| Proportion resolveda | 72% | 25% |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | 8.0 (2.7–18.7) | NA (14.0–NA) |

| Non-infectious pneumonitis | n = 20 | n = 0 |

| Proportion resolveda | 80% | 0 |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | 3.8 (1.3–7.1) | |

| Hyperglycemia and new onset of DM | n = 28 | n = 2 |

| Proportion resolveda | 46% | 50% |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | 29.1 (10.1–NA) | NA (3.0–NA) |

| Hyperlipidemia | n = 4 | n = 0 |

| Proportion resolveda | 25% | 0 |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | NA (19.3–NA) | |

| Infections and infestations | n = 32 | n = 4 |

| Proportion resolveda | 84% | 100% |

| Median time to resolution (week) (95% CI) | 3.0 (1.0–18.0) | 1.6 (0.3–2.9) |

CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; NA, not assessable (because of very low event rates); PBO, placebo.

aNumber of patients with grade 3/4 adverse events that resolved to grade ≤1. The denominator of the percentage is the total for that preferred term. For example, for stomatitis and related events with EVE therapy, the proportion of patients whose adverse event resolved to grade ≤1 was 38/39 × 100 = 97%.

pneumonitis

Overall, 20% of patients in the EVE + EXE arm had non-infectious pneumonitis or related events, compared with <1% in the PBO + EXE arm [13]. Grade 3 events occurred in 4% of patients and one grade 4 event was reported.

The time course for pneumonitis differed from stomatitis, with few early events and no appreciable plateau. Approximately one-quarter of events (grade ≥2) occurred within the first 12 weeks (cumulative risk, 5%). Cumulative risks of pneumonitis (grade ≥2) in the EVE + EXE arm were 10% and 16% at 24 and 48 weeks, respectively (Figure 1B). Among patients with grade 3 pneumonitis in the EVE + EXE arm, 80% experienced resolution to grade ≤1, typically following dose interruption/reduction, after a median of 3.8 weeks (Table 2). Complete resolution of grade ≥3 pneumonitis was reported in 75% of patients, after a median of 5.4 weeks.

hyperglycemia

At study entry, 9% of patients in the EVE + EXE arm and 10% in the PBO + EXE arm had diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance. During the study, more patients in the EVE + EXE arm (11%) developed grade ≥2 hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes mellitus compared with those receiving PBO + EXE (2%). The incidence of all-grade hyperglycemia and new-onset diabetes mellitus was higher in the EVE + EXE arm than in the PBO + EXE arm (16% versus 3%, respectively), with grade 3 or 4 events occurring in 6% and 1% of patients, respectively [13].

Approximately half of all hyperglycemia/new-onset diabetes mellitus events (grade ≥2) occurred within the first 6 weeks (cumulative risk, 7%). The cumulative risk at 48 weeks was 13% in the EVE + EXE arm compared with 3% in the PBO + EXE arm (Figure 1C). Among patients with grade 3 or 4 events in the EVE + EXE arm, 46% experienced resolution to grade ≤1 after a median of 29.1 weeks (Table 2).

fatigue

Fatigue was reported in 37% of patients in the EVE + EXE arm compared with 27% in the PBO + EXE arm (Table 2) [13]. Grade 3 or 4 events were more frequent in the experimental arm (grade 3, 4% versus 1%; grade 4, <1% versus 0%, respectively).

More than one-third of fatigue events (grade ≥2) occurred within 6 weeks of treatment initiation (cumulative risk, 11%). The cumulative risk at 48 weeks was 28% in the EVE + EXE arm and 20% in the PBO + EXE arm (Figure 1D). Among patients with grade 3 or 4 fatigue, 72% in the EVE + EXE arm experienced resolution, usually following dose interruption/reduction, to grade ≤1 after a median of 8.0 weeks (Table 2). Complete resolution was reported in 56% of EVE + EXE-treated patients after a median of 18.7 weeks. None of the patients in the PBO + EXE arm with grade 3 or 4 fatigue achieved complete resolution.

hyperlipidemia

Patients treated with EVE + EXE (14%) had a higher incidence of hyperlipidemia compared with those treated with PBO + EXE (2%). The combined incidence of grade 3 or 4 hyperlipidemia was 1% in the EVE + EXE arm and 0% in the PBO + EXE arm. The cumulative risk of hyperlipidemia (grade ≥2) at 48 weeks was 8% in the EVE + EXE arm.

dose interruptions and reductions/adjustments

Dose interruptions/reductions were required in 301 EVE patients (62%) and in 28 PBO patients (12%). The median duration of dose interruptions/reductions was higher with EVE (11 days) than with PBO (1 day) or EXE (1–2 days) (Table 3). Among 1065 instances of EVE dose interruptions/reductions, 463 (44%) resolved with resumption of full dosing; 352 of these events (76%) resolved within 2 weeks.

Table 3.

Incidence and median duration of dose reduction and interruption events and time to resumption of full study dose

| EVE | EXE | PBO | EXE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of dose reductions/interruptions | ||||

| Number of dose reductions/interruptions (n) | 1065 | 224 | 114 | 65 |

| Median duration (days) (range) | 11 (1–672) | 2 (1–47) | 1 (1–131) | 1 (1–20) |

| Number of dose reductions (n) | 360 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| Median duration (days) (range) | 29 (1–672) | 7 (7–7) | 20 (2–131) | 0 |

| Number of dose interruptions (n) | 705 | 223 | 105 | 68 |

| Median duration (days) (range) | 7 (1–41) | 2 (1–47) | 1 (1–26) | 1 (1–20) |

| Time to resumption of full drug dose | ||||

| ≤1 week [n (%)] | 219 (47) | 154 (69) | 88 (85) | 59 (87) |

| >1 and ≤2 weeks [n (%)] | 133 (29) | 44 (20) | 9 (9) | 7 (10) |

| >2 and ≤3 weeks [n (%)] | 55 (12) | 14 (6) | 4 (4) | 2 (3) |

| >3 weeks [n (%)] | 56 (12) | 11 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Median time to resumption of full dosea (days) (range) | 8 (2–333) | 3 (2–48) | 2 (2–27) | 2 (2–21) |

EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; PBO, placebo.

aIn patients who were able to resume study drug.

The most common AEs leading to dose interruptions/reductions (≥3% of patients) in the EVE + EXE arm (by preferred terms) were stomatitis (23.7%), pneumonitis (7.5%), alanine aminotransferase increase (4.6%), aspartate aminotransferase increase (4.4%), dyspnea (3.7%), blood creatinine increase (3.3%), and fatigue (3.1%). The difference between the actual incidence of dose modifications because of pneumonitis (7.5%) versus what may have been expected based on the proportion of patients with grade ≥2 pneumonitis events (8.9%) may be attributed to the fact that some patients discontinued treatment for pneumonitis, based on investigator discretion, without dose modification. No predominant AE led to dose interruptions/reductions in the PBO + EXE arm. Dose interruptions/reductions because of AEs were not substantially affected by patient age or last prior therapy (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

In the EVE + EXE arm, 163 patients (34%) required a dose reduction to 5 mg EVE/day (1 dose-level reduction). The median time to first dose reduction was 55 days (range, 6–483 days) in the overall population. The median time to first dose reduction in younger patients [<65 years: 52 days (range, 11–483 days)] was comparable with that observed in elderly patients [≥65 years: 60 days (range, 6–440 days)]. Thirteen patients re-escalated to the full EVE dose after being dose-reduced because of an AE (details provided in supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discontinuations because of AEs

The rates of treatment discontinuation because of treatment-emergent AEs were higher in the EVE + EXE arm (n = 485; 26% for EVE and 9% for EXE) compared with the PBO + EXE arm (n = 239; 5% for PBO and 3% for EXE). The most common AEs leading to treatment discontinuation in the EVE + EXE arm included pneumonitis (5.6%), stomatitis (2.7%), dyspnea (2.3%), and fatigue (1.9%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment

| Adverse event (%) | EVE + EXE (n = 482) |

PBO + EXE (n = 238) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | |

| Pneumonitis | 5.6 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Rash | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lung infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 0.2 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; PBO, placebo.

discussion

In BOLERO-2, the EVE + EXE combination significantly improved PFS compared with PBO + EXE in postmenopausal women recurring or progressing on NSAIs; toxicity was well-managed by dose interruption and reduction [3]. In the current analyses, representing 10 months of additional follow-up, no new or unexpected safety signals were observed with EVE + EXE, and the AE profile was consistent with earlier interim reports and previous reports of EVE in BC and other oncology settings [3, 9–11]. Class-effect AEs (except pneumonitis) had a relatively short time to onset, and the incidence tapered off thereafter. Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred at a low rate, and most resolved to grade ≤1 fairly rapidly. Management recommendations for EVE-related AEs included dose interruptions/reductions and facilitated continued treatment in most cases (perspectives on current guidelines for managing AEs of interest are presented in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The incidences of some mTOR inhibitor class-effect AEs, such as stomatitis, rash, and non-infectious pneumonitis, were previously reported to be slightly higher among Asian than Caucasian patients in BOLERO-2 [17]. This was also observed with EVE in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RECORD-1) [18]. However, the incidences of higher-grade AEs requiring dose interruption/adjustment in BOLERO-2 were similar in Asians and Caucasians, supporting generally similar efficacy and tolerability of EVE among different racial subgroups. Consistent with previous clinical studies evaluating mTOR inhibitors versus endocrine agents, 12% of patients in the PBO + EXE arm experienced stomatitis or related events. This may reflect general vigilance by trial investigators toward class-effect AEs with the drugs under study [15, 16, 19]. Notably, the incidence and severity of AEs reported in this study were consistent with historical data, and the double-blinded trial design precluded bias in AE reporting. Dose interruptions/adjustments were also not affected by patient age, last prior chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy. Older patients did not experience significantly different rates of AEs necessitating dose interruptions/adjustments, despite a potentially higher prevalence of comorbidities and concomitant medications. The duration of dose interruptions/reductions was relatively short, and most patients who resumed the full 10 mg EVE dose did so within 2 weeks, thereby maintaining dose intensity.

Despite EVE dose interruptions/reductions, a significant improvement in efficacy was seen, supporting the timely management of AEs. Dose-modification guidelines, including treatment discontinuation, have been established for managing non-hematologic AEs during EVE therapy (Table 1) [7]. Careful application of established AE management recommendations as well as patient education about the time course of AE onset and resolution may improve tolerability and treatment adherence. Given the potential for prolonged use of EVE in patients with HR+, HER2-negative advanced BC, optimal patient safety and benefit from this therapy are contingent upon clinicians' ability to recognize, monitor, and effectively manage class-effect toxicities associated with EVE therapy.

In conclusion, these results expand our understanding of the benefits, tolerability, and risks of EVE + EXE in postmenopausal women with HR+ advanced BC progressing after letrozole or anastrozole and provide important data critical for management of toxicity. The AE profile of EVE does not overlap with existing systemic therapies. Most EVE-emergent AEs were mild or moderate and were manageable. Understanding the time course of AEs will allow appropriate patient education, inform frequency of monitoring, and aid in the development of prevention and treatment strategies; it is particularly important given the clinical benefit obtained from adding EVE to EXE and the differential toxicities associated with this targeted agent.

funding

Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. BOLERO-2 was supported by Novartis.

disclosure

HSR has received grant support to the Regents of the University of California from Pfizer, Novartis, and Merck; and has received travel support from Novartis. KIP has served as a consultant with Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Abraxis, Amgen, and GlaxoSmithKline; has received research funding either directly through per-case funding for studies or indirectly through the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group; has contracted with pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen, Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Ortho Biotech; has participated in speaker's bureaus or received honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Amgen; has given paid expert testimony for Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has served as an advisory committee member for Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Amgen. MG has received research support from Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis, Roche, and Pfizer; and has received honoraria from Amgen, Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Sandoz, AstraZeneca, GenomicHealth, and Nanostring Technologies. SN has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda; and has received honoraria from or been part of speaker's bureaus or advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda. MP has served as a board member for PharmaMar; has been a consultant for Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and Bayer; has received grant support from Pfizer, Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis; and has received honoraria from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Amgen, Sanofi-Aventis, and AstraZeneca. GH has served as a consultant to Myriad, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Galena, Novartis, Genentech, and Sanofi-Aventis; has received grant support from Novartis; and has received travel expense reimbursement from Novartis, Genentech, and Sanofi-Aventis. JB has served as a consultant to Novartis, Roche, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Verastem, Bayer, Chugai, Exelixis, Onyx, and Constellation. EC has received research support from Novartis for the BOLERO-2 study. PP has received research support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Roche. HB and ME-H are employed by Novartis. TT is employed by and owns stock/stock options in Novartis. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank Marithea Goberville, PhD, and Jerome F. Sah, PhD, of ProEd Communications, Inc., for their medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. The scientific steering committee for the trial included José Baselga, Martine Piccart, Howard A. Burris III, Hope S. Rugo, Shinzaburo Noguchi, Michael Gnant, Kathleen I. Pritchard, and Gabriel N. Hortobagyi.

references

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. , Version 2.2013 www.nccn.com. (5 July 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, et al. 1st International consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 1) Breast. 2012;21:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller TW, Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2406–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI41680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeram M, Tan QT, Tekmal RR, et al. Akt-induced endocrine therapy resistance is reversed by inhibition of mTOR signaling. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1323–1328. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulay A, Rudloff J, Ye J, et al. Dual inhibition of mTOR and estrogen receptor signaling in vitro induces cell death in models of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5319–5328. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2012. Afinitor® (everolimus) tablets [package insert] http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022334s016lbl.pdf. (5 July 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horsham, UK: Novartis Europharm Limited; 2012. Afinitor® (everolimus) tablets [summary of product characteristics] http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001038/WC500022814.pdf. (5 July 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116:4256–4265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4311–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck JT, Rugo HS, Burris HA, et al. BOLERO-2: health-related quality-of-life in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with everolimus and exemestane versus exemestane. The ASCO Annual Meeting (Poster 539); Chicago, IL. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccart M, Noguchi S, Pritchard KI, et al. Everolimus for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: updated results of the BOLERO-2 phase III trial. The ASCO Annual Meeting (Poster 559); Chicago, IL. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v3.0 (CTCAE) 2006. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf. (5 July 2013, date last accessed)

- 15.Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2630–2637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a GINECO study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2718–2724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noguchi S, Masuda N, Iwata H, et al. Efficacy of everolimus with exemestane versus exemestane alone in Asian patients with HER2-negative, hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer in BOLERO-2. Breast Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0444-8. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsukamoto T, Shinohara N, Tsuchiya N, et al. Phase III trial of everolimus in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: subgroup analysis of Japanese patients from RECORD-1. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:17–24. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff AC, Lazar AA, Bondarenko I, et al. Randomized phase III placebo-controlled trial of letrozole plus oral temsirolimus as first-line endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:195–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.