Abstract

Recent studies indicate that a complex relationship exists between autophagy and apoptosis. In this study we investigated a regulatory relationship between autophagy and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells utilizing molecular and biochemical approaches. For this study, human colorectal carcinoma HCT116 and CX-1 cells were treated with two chemotherapeutic agents—oxaliplatin, which induces apoptosis, and bortezomib, which triggers both apoptosis and autophagy. A combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib caused a synergistic induction of apoptosis which was mediated through an increase in caspase activation. The combinational treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib promoted the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway which modulated the synergistic effect through the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway. JNK signaling led to Bcl-xL phosphorylation at serine 62, oligomerization of Bax, alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential, and subsequent cytochrome c release. Overexpression of dominant-negative mutant of Bcl-xL (S62A), but not dominant-positive mutant of Bcl-xL (S62D), suppressed cytochrome c release and synergistic death effect. Interestingly, Bcl-xL also affected autophagy through alteration of interaction with Beclin-1. Beclin-1 was dissociated from Bcl-xL and initiated autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib. However, activated caspase 8 cleaved Beclin-1 and suppressed Beclin-1-associated autophagy and enhanced apoptosis. A combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib-induced Beclin-1 cleavage was abolished in Beclin-1 double mutant (D133AA/D149A) knock-in HCT116 cells, restoring the autophagy-promoting function of Beclin-1 and suppressing the apoptosis induced by the combination therapy. In addition, the combinatorial treatment significantly inhibited colorectal cancer xenografts’ tumor growth. An understanding of the molecular mechanisms of crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy will support the application of combinatorial treatment to colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Oxaliplatin, Bortezomib, Mitochondria-dependent pathway, Bcl-xL, Beclin-1

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers in both men and women in the United States, and is also the third leading cause of cancer deaths among men and women [1]. Significant improvements have been made in the management of this disease mainly through surgery followed by post-surgical chemotherapy [2]. Although multiple large clinical trials are underway evaluating the best way to combine or sequence agents, unfortunately, advanced unresectable colorectal cancer still remains incurable. Moreover, sometimes chemotherapeutic agents have potentially serious side effects which resulted in mortality in clinical trials [3]. Therefore, new approaches to overcome negative effects are obviously necessary. One of these approaches is the use of combination treatments with the goal of reducing side effects as well as achieving synergistic anticancer activity, which is greater than that of single agents administered alone.

Current colorectal cancer therapy regimens are based on the surgical removal of solid tumor masses, usually combined with a series of chemical treatments; however, chemotherapy reaches a plateau of efficacy as a treatment modality with the emergence of resistant tumors. Despite the wide variety applied, most new drugs are thought to ultimately induce apoptosis of tumor cells through mitochondrial or death-receptor pathways, even though these pathways are often defective in cancer. However, recently, other cell death mechanisms are being considered for therapeutic application, such as autophagy and necrosis [4–6]. Like apoptosis, autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process which is implicated in the regulation of cell fate in response to cytotoxic stress [7]. Besides its function as a cytoprotective mechanism, autophagy can contribute to both caspase-dependent and independent programmed cell death [8, 9]. Interestingly, certain molecules which are essential for the regulation of autophagy have also been reported to play a key role in the regulation of apoptosis [10, 11], evidence for crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy during cell death. In this present study, we examined the effectiveness of combining oxaliplatin, which induces apoptosis, with bortezomib, which induces both apoptosis and autophagy, to determine their potentially synergistic effects on tumoricidal activity in colorectal cancer.

Oxaliplatin, a second-generation platinum analog, has evolved as one of the most important therapeutic agents in metastatic colorectal cancer and stage II/III colon cancer [12]. Oxaliplatin can induce damage to tumors via induction of apoptosis through Bax oligomerization on the mitochondria and cytochrome c release in the cytoplasm [13, 14]. Oxaliplatin can be safely combined with drugs such as fluoropyrimidine and irinotecan, resulting in increased response rates and delayed tumor progression [15–17].

Bortezomib (Velcade) is well known as a potent proteasome inhibitor inducing both autophagy and apoptosis [18, 19], and although bortezomib has been applied largely to treatment of hematopoietic malignancies such as myeloma, currently it has shown some evidence of activity in other malignancies such as renal cell carcinoma, advanced non-small cell lung cancer, and mantle cell lymphoma [20, 21]. Its mode of action is mediated through reversible binding to the N-terminus threonine residue in the β-1 subunit of the catalytic core complex of the 26S proteasome, leading to reversible inhibition of the proteolytic activity of the proteasome. This, in turn, leads to the modulation of several biological alterations including the augmentation of cell cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, deregulation of NF-κB activity, and induction of ER stress [22, 23].

Our hypothesis was that oxaliplatin and bortezomib would act synergistically to induce apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines through interaction between apoptosis and autophagy. We observed that a combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib effectively activates the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway by activating the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway. Moreover, Beclin-1 is dissociated from Bcl-xL and initiates autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin/bortezomib. However, activated caspase 8 cleaves Beclin-1 and suppresses Beclin-1-associated autophagy and enhances apoptosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

The human colorectal carcinoma HCT116 wild-type (WT) and Bax-deficient (Bax−/−) cell lines which were kindly provided by Dr. B Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA). Human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 cells, which were obtained from Dr. JM Jessup (National Cancer Institute), were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) containing 10 % FBS. Every cell was kept in a 37°C humidified incubator with a mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2.

2.2. Reagents and antibodies

Oxaliplatin was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. and bortezomib was from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). Anti-PARP, anti-caspase 8, 9, 3, anti-cleaved caspase 3, anti-phosphorylated (Thr183/Tyr185) JNK, anti-JNK, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-COX-IV and anti-human influenza hemagglutinin (HA) antibody were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-phosphorylated Bcl-xL (S62) antibody was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) and anti-cytochrome c antibody was from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibody were from Sigma (St. Louis MO, USA).

2.3. Drug treatment

Concentrations and dosage of drugs for the in vitro and in vivo experiments were chosen from our previous studies and the published literature [24–28]. Drug treatments for in vitro or in vivo were accomplished by aspirating the medium and replacing it with new medium containing drugs or by intraperitoneal injection, respectively.

2.4. Survival assay

For trypan blue exclusion assay, trypsinized cells were pelleted and resuspended in 0.2 ml of medium, 0.5 ml of 0.4% trypan blue solution, and 0.3 ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). The samples were mixed thoroughly, incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and visualized by light microscopy. At least 300 cells were counted for each survival determination. All experiments were repeated three times.

2.5. Annexin V binding

The translocation of phosphatidylserine, one of the markers of apoptosis, from the inner to the outer leaflet of plasma membrane was detected by binding of allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated Annexin V. HCT116 cells were plated, treated with drugs for 24 hours and stained with mouse anti-human Annexin V antibody and propidium iodide (PI). The staining was terminated and cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.6. Protein extracts and PAGE

Cells were scraped with 1 × Laemmli lysis buffer (including 2.4 M glycerol, 0.14 M Tris (pH 6.8), 0.21 M SDS, and 0.3 mM bromophenol blue) and boiled for 3 min. Protein concentrations were measured with BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The samples were diluted with 1 × lysis buffer containing 20 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT), and an equal amount of protein was loaded on 10-15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed using a Hoefer gel apparatus (Hoefer, Holliston, MA, USA).

2.7. Immunoblot analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS-Tween 20 (0.05%, v/v) for 30 minutes. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG was used as the secondary antibody. Immunoreactive protein was visualized by the enhanced chemi-luminescence protocol (ECL, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Quantitation of X-ray film was carried out by scanning densitometer (Personal Densitometer, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using area integration.

2.8. Bax oligomerization

After drug treatment, cells were collected and resuspended in homogenization buffer. The cell suspension was homogenized several times and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to obtain nuclear pellets. Supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 ml tube and spun at 10,000 ×g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet the mitochondria. Isolated mitochondrial fractions and cytosolic fractions were cross-linked with 1 mmol/L dithiobis (Pierce) for 1 hour at room temperature. After cross-linking, the mitochondria were pelleted and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE under nondenaturing conditions followed by immunoblotting for Bax.

2.9. Cytochrome c release assay

To determine the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, HCT116 cells growing in 100 mm dishes were used. After drug treatment, mitochondrial and cytosol fractions were prepared by using Mitochondrial Fractionation Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) from treated cells following company instructions and reagents included in the kit. Cytosolic fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-cytochrome c antibody. Equal loading of the mitochondrial pellets was confirmed with anti-COX IV antibody.

2.10. JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential assay

After drug treatment, cells were stained using JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential detection kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 10 minutes and analyzed by flow cytometry. Fluorescence intensity was measured with the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, Inc., San Jose, MI, USA). Results were analyzed with VenturiOne software (Applied Cytometry, Inc., Plano, TX, USA).

2.11. Immunoprecipitation

Briefly, cells were pelleted and lysed by CHAPS buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail. Cell lysates were completely disrupted by repeated aspiration through a 27 gauge needle. Cell debris was removed and protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay Reagent. For immunoprecipitation, 500 μg of lysate was incubated with 1 μg of rabbit anti-HA antibody or rabbit IgG at 4°C overnight, followed by the addition of protein G-agarose beads and rotation at 4°C for 4 hours. Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation and the pellet was dissolved in electrophoresis sample buffer for heat denaturation. The immune complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis.

2.12. Stable transfection

To evaluate the effect of Bcl-xL phosphorylation at S62 on its own antiapoptotic activity, we established CX-1-derived cell lines. Cells were transfected with human Bcl-xL tagged with HA epitope in pCDNA3.1 vector: HA-Bcl-xL-WT, HA-Bcl-xL S62A (serine 62 alanine), HA-Bcl-xL S62D (serine 62 asparagine; a kind gift from Dr. Timothy C. Chambers, University of Arkansas), or the corresponding empty vector (pCDNA). Cells were selected with 1 mg/ml G418 for 2 weeks and five clones were pooled and then maintained in 500 μg/ml G418.

2.13. Animal model

For the subcutaneous model, human colorectal HCT116 tumors were established by subcutaneously injecting 1 × 106 cells into the left thigh of 6-week old male nude mice (Balb/c nude) (Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA, USA). Prior to treatment with oxaliplatin (10 mg/kg) with/ without bortezomib (0.25 mg/kg), tumor size was measured 2-3 times per week until the volume reached above 200 mm3. Tumor volume was calculated as width × length × height × 0.52. After establishment of these tumor xenografts, mice were randomized into four groups of five mice per group. Oxaliplatin was administered by intraperitoneal injection. One hour later, bortezomib was administrated by intraperitoneal injection. Mice were fed ad libitum and maintained in environments with controlled temperature of 22–24°C and 12 hour light and dark cycles. All animal experiments were carried out at the University of Pittsburgh in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.14. TUNEL assay

The TUNEL method was used to detect apoptotic cells. An in situ cell apoptosis detection kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used. The staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Tissue sections in the vehicle group were stained and served as negative controls. Briefly, sections of paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized then washed with TBS buffer and permeabilized with proteinase K. DNA strand breaks were then end-labeled with terminal transferase, and the labeled DNA was visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

2.15. Statistical analysis

The significance between sham versus all other groups was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni t test for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad InStat 3 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was set at values of †,* (p < 0.05), ††, ** (p < 0.01), or †††, *** (P < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Synergistic induction of apoptosis by oxaliplatin in combination with bortezomib

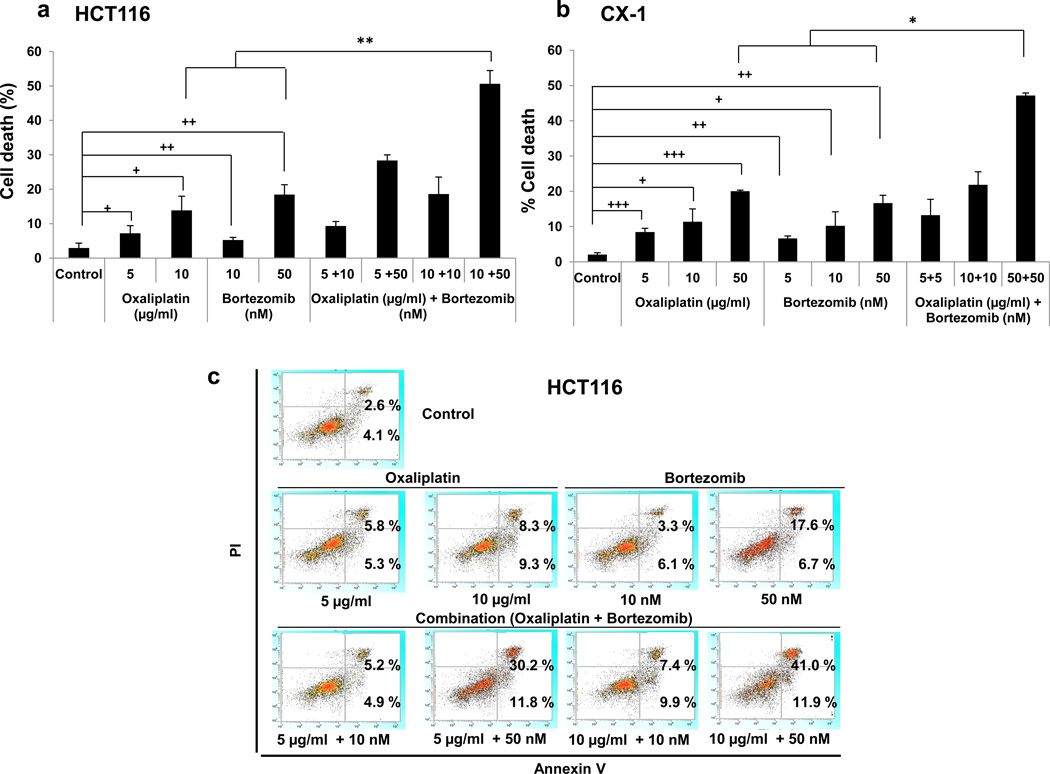

To investigate the effect of oxaliplatin and bortezomib on cell viability, human colorectal carcinoma HCT116 cells or human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of oxaliplatin and/or bortezomib. As the doses of oxaliplatin or bortezomib increased, cell deaths were significantly increased in both cell lines (Fig. 1a and 1b). In particular, the combinatorial therapy with oxaliplatin and bortezomib caused a synergistic cell death compared with single treatment in both cell lines (HCT116, p < 0.01 and CX-1, p < 0.05). To clarify whether oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced cytotoxicity is associated with apoptosis, we used the Annexin V assay (Fig. 1c). For flow cytometry assay, HCT116 cells were treated in the absence or presence of oxaliplatin/bortezomib and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Late apoptotic death cells and early apoptotic death cells were observed in the upper right quadrant of the plots and the lower right quadrant of the plots, respectively. Data from cytometry assay clearly showed a synergistic induction of apoptosis by combined treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib.

Figure 1. Oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced cytotoxicity in colon cancer cells.

HCT116 (a, c) and CX-1 (b) cells were treated with various concentrations of oxaliplatin/bortezomib for 24 hours. (a) and (b) Cell death was analyzed by the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. Cross †, ††, or ††† represents a statistically significant difference at P <0.05, P <0.01, or <0.001, respectively. Asterisk * or ** represents a statistically significant difference at P <0.05 or P <0.01, respectively. (c) After drug treatment, cells were stained with fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC)-Annexin V and PI. Apoptosis was detected by the flow-cytometric assay.

3.2. Synergistic induction of apoptosis by oxaliplatin and bortezomib is mediated through an increase in caspase activation

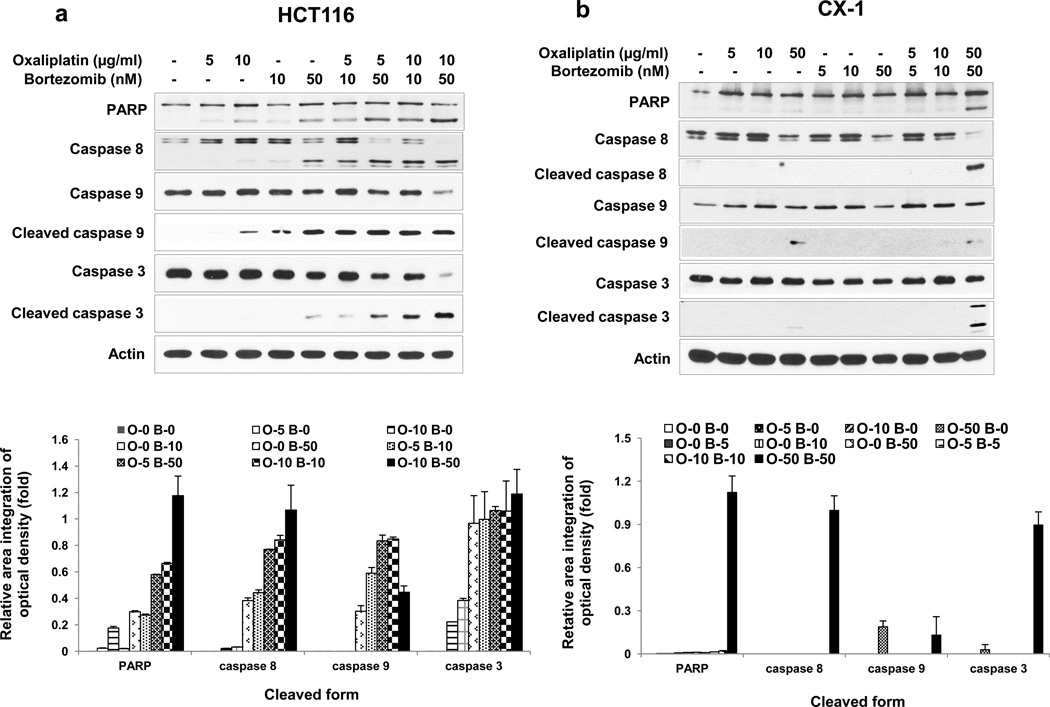

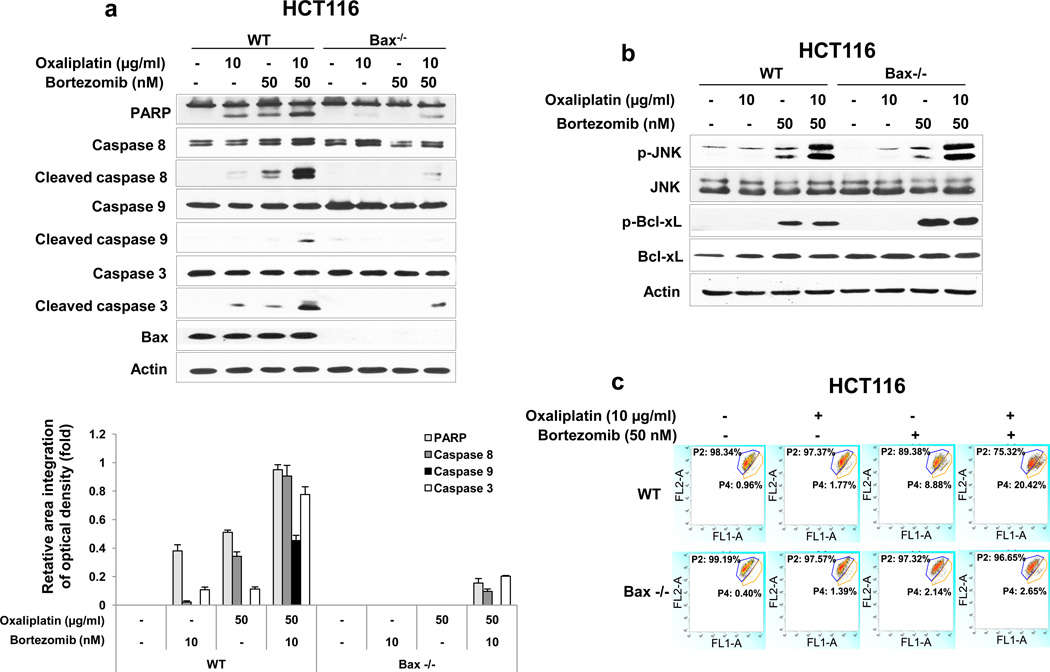

Synergistic effects were also confirmed by determining the hallmark of apoptosis, PARP cleavage (Figs. 2a and 2b). Based on our results showing that combined treatment enhanced apoptosis, we examined whether the combinatorial treatment promoted caspase pathways. Data from Figs. 2a and 2b show that treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib increased the cleavage (activation) of caspase 8/9/3. Figure 2a shows that cleaved caspase 3 was not detected when HCT116 cells were treated with 10 μg/ml oxaliplatin alone for 24 hours. However, cleaved caspase 3 was detected with the same treatment in Figure 4a. This discrepancy is probably due to varying x-ray film exposure time when the membrane was exposed to an x-ray film to record the chemiluminescence. Next, we examined the kinetics of oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced apoptosis. The activation of individual caspases was investigated by western blot analysis upon 4, 8, 14 and 24 hours of treatment (Fig 2c and 2d). Synergistic apoptosis and activation of caspases occurred within 14 or 24 hours in HCT116 cells or CX-1 cells, respectively. These results suggest that synergistic induction of apoptosis by treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib is mediated through an increase in caspase activation.

Figure 2. Oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced apoptotic death in colon cancer cells.

a and b, HCT116 (a) and CX-1 (b) cells were treated with various concentrations of oxaliplatin/bortezomib for 24 hours. After drug treatment, the cleavage of caspase 8, 9, 3 or PARP was detected by immunoblotting (upper panels). Actin was used to confirm the equal amount of proteins loaded in each lane. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the cleaved forms of caspase 8, 9, 3 or PARP was performed (lower panels). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (c) and (d) Kinetics of oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells (c) or CX-1 cells (d) were examined by treatment with 10 μg/ml oxaliplatin or/and 50 nM bortezomib for various times. After treatment, the cleavage of caspase 8, 9, 3 or PARP was detected by immunoblotting (upper panels). Actin was shown as an internal standard. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the cleaved forms of caspase 8, 9, 3 or PARP was performed (lower panels). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments.

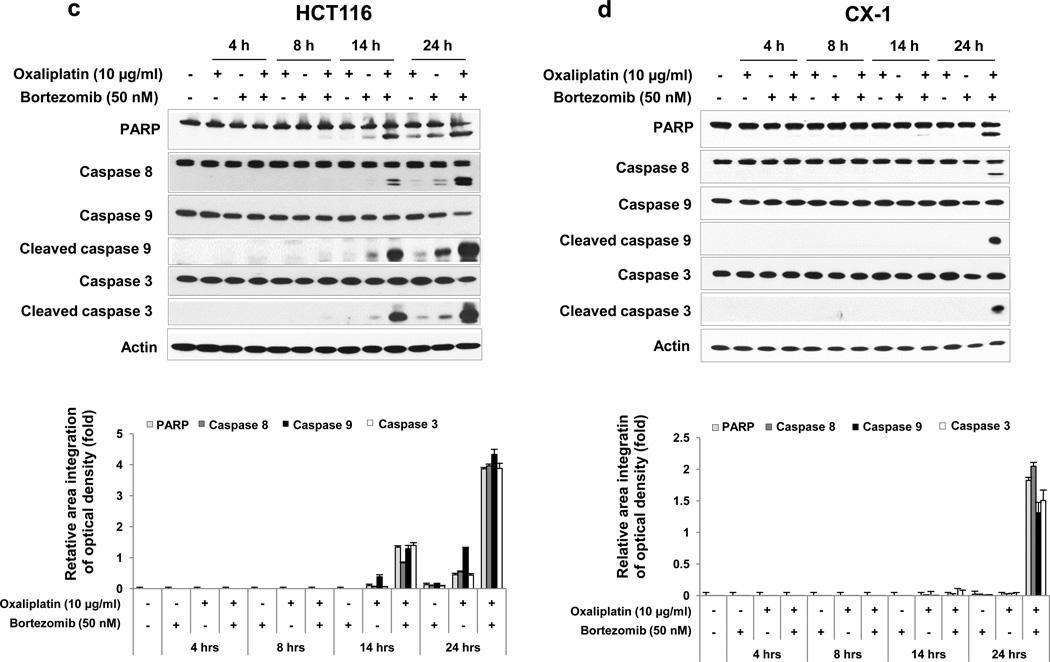

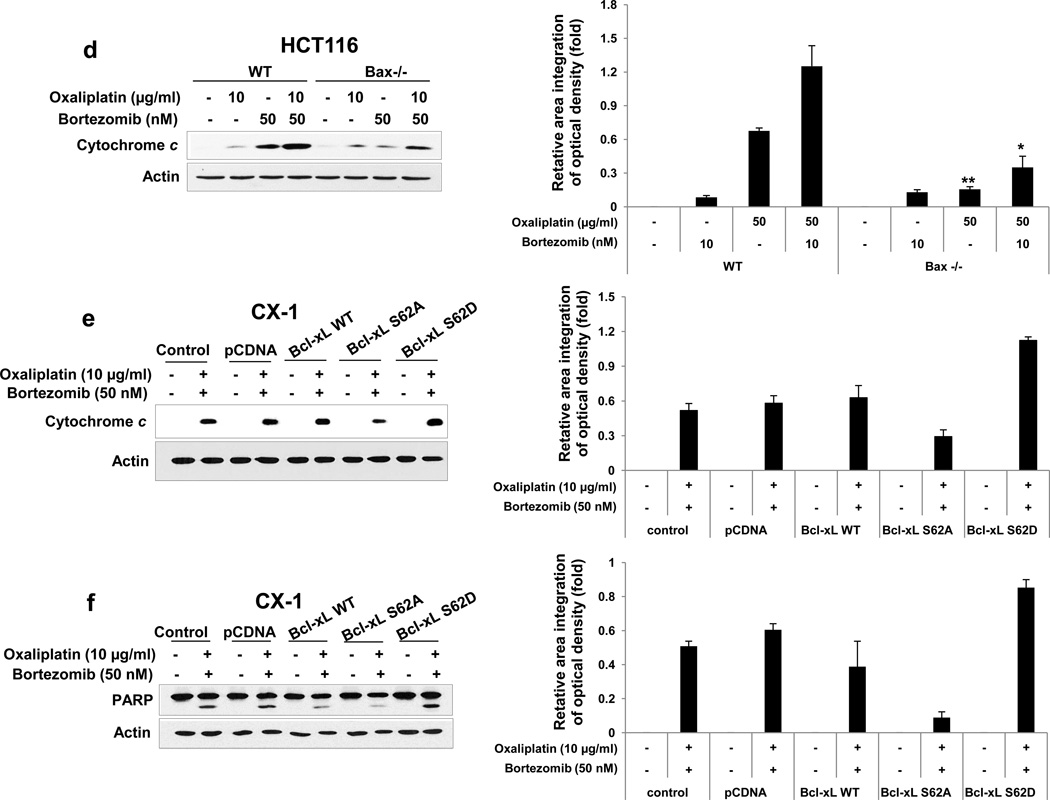

Figure 4. Role of Bax and subsequent cytochrome c release during treatment with oxaliplain/bortezomib.

(a) and (b) HCT116 wild-type (WT) and HCT116 Bax−/− cells were treated with oxaliplatin/ bortezomib for 24 hours. (a) Lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PARP, anti-caspase 8/9/3, or anti-Bax antibody (upper panel). Densitometry analysis of the bands from the cleaved forms of caspase 8, 9, 3 or PARP was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (b) Also cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-JNK (p-JNK), anti-JNK, anti-phospho-Bcl-xL (p-Bcl-xL), or anti-Bcl-xL antibody. Actin was shown as an internal standard. (c) HCT116 WT and HCT116 Bax−/− cells were treated with oxaliplatin/bortezomib and stained with JC-1 and then analyzed by flow cytometry to examine alterations of mitochondrial potential. (d) In the same experimental set, cytochrome c release into cytosol was determined by immunoblotting for cytochrome c in the cytosolic fraction (left panel). Actin was used to confirm the equal amount of proteins loaded. Densitometry analysis of the bands from released cytochrome c was performed (right panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. Asterisk * or ** represents a statistically significant difference at P <0.05 or P <0.01, respectively. (e) and (f) CX-1 cells were stably transfected with control plasmid, HA-Bcl-xL WT, HA-Bcl-xL S62A, or HA-Bcl-xL S62D plasmid and then treated with oxaliplatin and bortezomib for 24 hours. After treatment, cytosolic fractions were isolated and cytochrome c release into cytosol (e) or lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and PARP cleavage (f) was determined by immunoblotting (left panels). Actin was used to confirm the equal amount of proteins loaded. Densitometry analysis of the bands from released cytochrome c (e) or cleaved form of PARP (f) was performed (right panels). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments.

3.3. Role of the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway in the combinatorial treatment-induced apoptosis

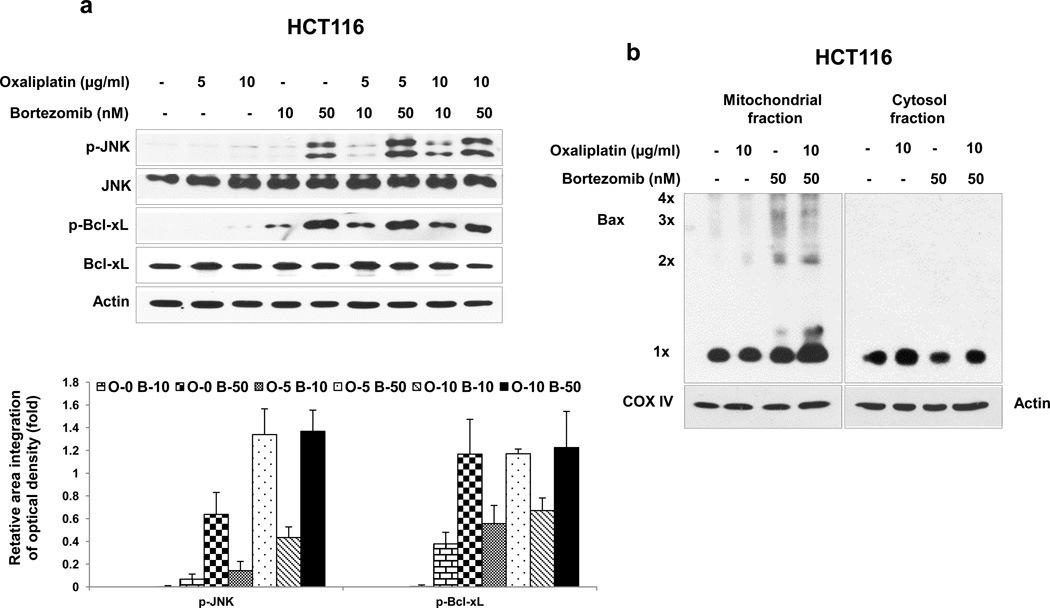

Previous studies have demonstrated that the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway is a key pathway in response to treatment with apoptotic agents [25, 29]. The role of the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway in synergistic induction of apoptosis by treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib was investigated. Phosphorylation of JNK and Bcl-xL was observed during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3a). Similar results were observed in CX-1 cells (data not shown). Interestingly, a large amount of phospho-JNK and phospho-Bcl-xL was detected in the treatment with high dose of bortezomib (50 nM). The combinatorial treatment with low doses (10 μg/ml oxaliplatin and 10 nM bortezomib) allows observation of the phosphorylation of JNK and Bcl-xL at doses for which each drug alone is less effective. Pretreatment with SP600125, an inhibitor of JNK, significantly reduced phosphorylation of Bcl-xL (data not shown). We previously reported that phosphorylation of Bcl-xL alters the interactions between Bcl-xL and Bax and then leads to Bax oligomerization [25]. Bax oligomerization occurred during treatment with bortezomib and oxaliplatin (Fig. 3b). We examined the involvement of Bax in the combinatorial treatment-induced apoptosis by determining the cleavage of PARP and caspase 8/9/3. Data from Fig. 4a clearly demonstrate that oxaliplatin and bortezomib-induced apoptosis and caspase activation were effectively suppressed in Bax-deficient cells. However, oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced phosphorylation of JNK and Bcl-xL was not affected in Bax-deficient HCT116 cells (Fig. 4b). These results confirmed that the JNK-Bcl-xL pathway is upstream of Bax. Oligomerized Bax bound to the mitochondria altered mitochondrial membrane potential (ref. 25, Figs. 4c). The alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential and cytochrome c release were substantially suppressed in Bax-deficient cells (Figs. 4c and 4d). To examine whether phosphorylation of the S62 residue on Bcl-xL is important for cytochrome c release, CX-1 cells were stably transfected with HA-Bcl-xL WT, phospho-defective HA-Bcl-xL S62A, or phospho-mimic HA-Bcl-xL S62D. Figures 4E and 4F show that HA-Bcl-xL S62A, but not HA-Bcl-xL WT and HA-Bcl-xL S62D, effectively inhibited cytochrome c release as well as apoptosis. These results confirmed that the phosphorylation of Bcl-xL plays an important role in the combinatorial treatment-induced apoptosis.

Figure 3. Role of the JNK-Bcl-xL pathway in Bax oligomerization.

(a) and (b) HCT116 cells were treated with oxaliplatin/bortezomib for 24 hours. (a) Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-JNK (p-JNK), anti-JNK, antiphospho-Bcl-xL (p-Bcl-xL), or anti- Bcl-xL antibody (upper panel). Actin was shown as an internal standard. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the phosphorylated forms of JNK or Bcl-xL was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (b) After the drug treatment, mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions from HCT116 cells were isolated and proteins were cross-linked with 1 mM dithiobis (succinimidyl propionate) and then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-Bax antibody. Bax monomer (1×) and multimers (2×, 3×, and 4×) are indicated. Actin was used as a cytosolic marker and COX IV as a mitochondrial marker.

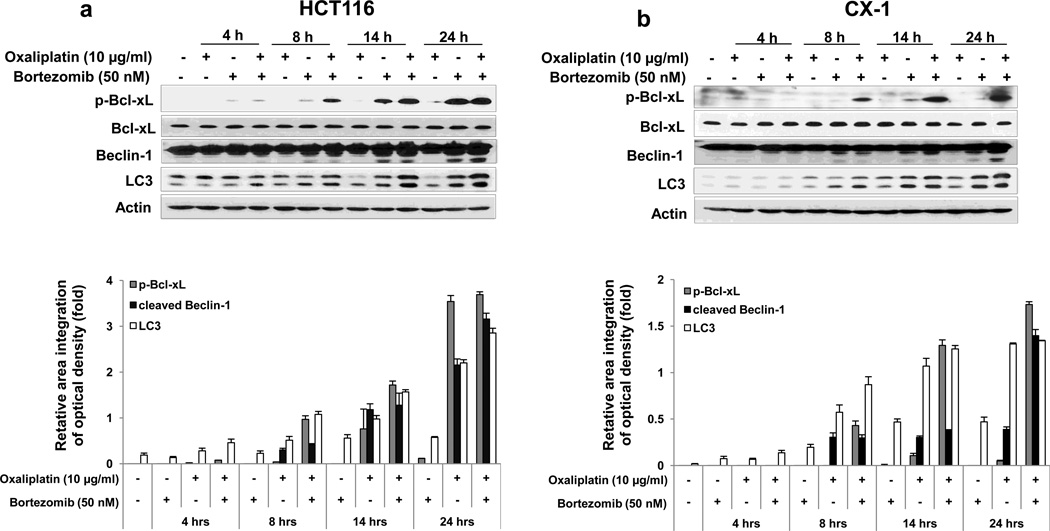

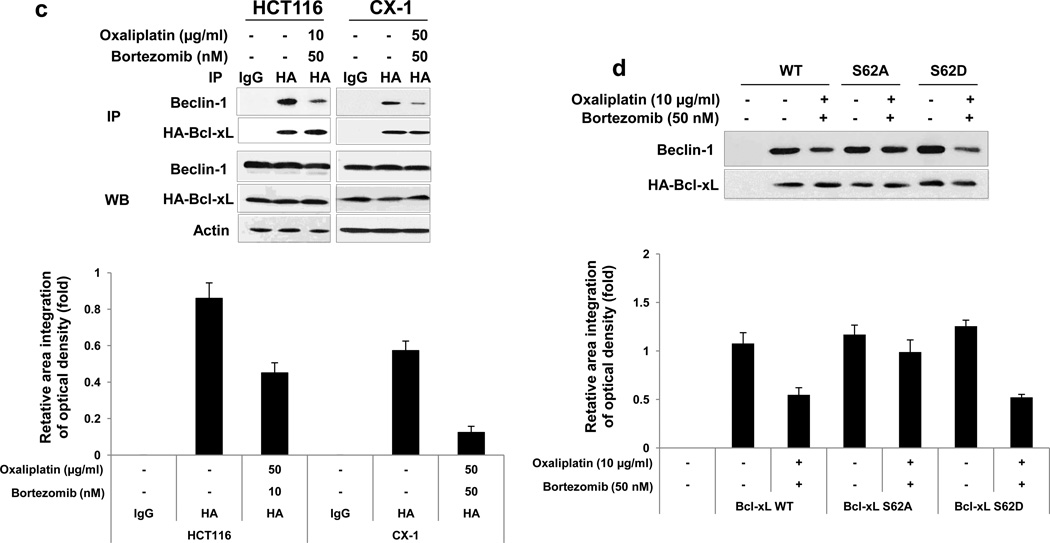

3.4. Role of Bcl-xL/Beclin-1 in oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced apoptosis and autophagy

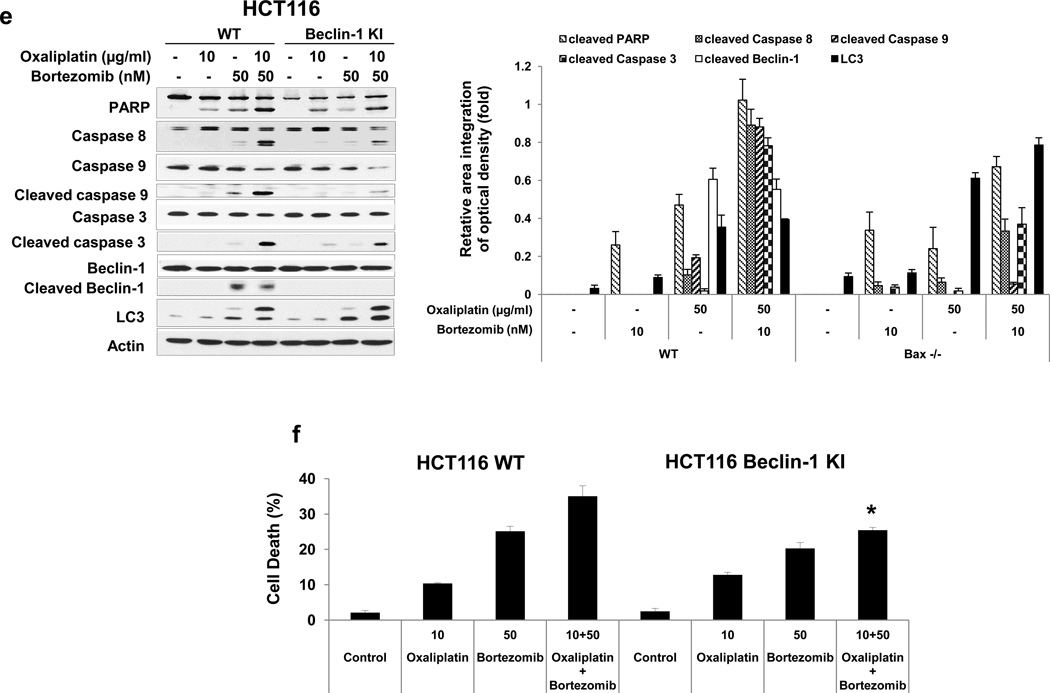

It is reported that Bcl-xL plays important roles in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis [30, 31]. Bcl-xL binds to Bcl-2-interacting protein-1 (Beclin-1), which, when bound to class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase (class III PI3K), initiates the formation of the autophagosome, and the interaction of Bcl-xL and Beclin-1 inhibits Beclin-1-mediated autophagy [32–36]. To examine the role of Bcl-xL/Beclin-1 in interplay between apoptosis and autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib, first, we observed the kinetics of oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced autophagy in colon cancer cells. Figs. 5a and 5b show that concurrent with phosphorylation of Bcl-xL, Beclin-1 was cleaved and LC3-II, the hallmark of autophagy, was increased, especially in the combinatorial treatment, in HCT116 and CX-1 cells. We further examined whether Beclin-1 was dissociated from Bcl-xL during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib. We observed that Beclin-1 was dissociated from Bcl-xL in both cell lines (Fig. 5c). Overexpression of dominant-negative mutant of Bcl-xL (S62A), but not dominant-positive mutant of Bcl-xL (S62D), suppressed the dissociation of Beclin-1 from Bcl-xL (Fig. 5d). Next, we examined the role of Beclin-1 in interplay between apoptosis and autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib. Previous studies have shown that Beclin-1 has two cleavage sites at D133 and D149 residues [37] and that Beclin-1 is cleaved by caspase 8, and C-terminal fragment of Beclin-1 (Beclin-1-C) localizes at the mitochondria and then induces cytochrome c release [37, 38]. Data from Beclin-1 double mutant (D133AA/D149A) knock-in HCT116 cells showed suppression of cleavage of PARP and caspase 8/9/3 (apoptosis) and increase in LC3-II (autophagy) (Fig. 5e). Also, we examined cell death in HCT116 and Beclin-1 double mutant (D133AA/D149A) knock-in HCT116 cells (Fig 5f). We observed significant decrease of cell death in Beclin-1 double mutant (D133AA/D149A) knock-in HCT116 cells compared with HCT116 in combinatorial treatment especially (p < 0.05). These results suggest that Beclin-1 is dissociated from Bcl-xL and initiates autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin/ bortezomib. However, activated caspase 8 cleaves Beclin-1 and suppresses Beclin-1-associated autophagy and enhances apoptosis.

Figure 5. Role of Beclin-1 in oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced cell death.

Kinetics of oxaliplatin/bortezomib-induced Bcl-xL phosphorylation and Beclin-1 in HCT116 cells (a) or CX-1 cells (b) were examined by treatment with 10 μg/ml oxaliplatin or/and 50 nM bortezomib for various times. After treatment, anti-phospho-Bcl-xL (p-Bcl-xL), anti-Bcl-xL, anti-Beclin-1 or anti-LC3 antibody was detected by immunoblotting (upper panels). Actin was shown as an internal standard. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the phosphorylated forms of Bcl-xL, cleaved forms of Beclin-1, or LC3-II was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (c) HCT116 or CX-1 cells were stably transfected with HA-tagged Bcl-xL plasmid. Cells were treated with oxaliplatin/bortezomib for 24 hours. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody or mock antibody (IgG) and immunoblotted with anti-Beclin-1 or anti-HA antibody (top of upper panel). The presence of HA-Bcl-xL and Beclin-1 in the lysates was verified by immunoblotting (bottom of upper panel). Actin was shown as an internal standard. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the immunoprecipitated Beclion-1 was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (d) CX-1 cells were stably transfected with HA-Bcl-xL WT, HA-Bcl-xL S62A, or HABcl-xL S62D plasmid and then treated with oxaliplatin and bortezomib for 24 hours. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody or mock antibody (IgG) and immunoblotted with anti-Beclin-1 or anti-HA antibody. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the immunoprecipitated Beclion-1 was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (e) and (f), HCT116 cells and HCT116 Beclin-1 knock-in cells were treated with oxaliplatin/bortezomib for 24 hours. (e) Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-PARP, anti-caspase 8/9/3, anti-Beclin-1, or anti-LC3 antibody (left panel). Actin was shown as an internal standard. Densitometry analysis of the bands from the cleaved forms of capase 8, 9, 3, PARP, Beclin-1, or LC3-II was performed (lower panel). Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. (f) In the same experimental set, cell death was analyzed by the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent SD from triplicate experiments. Asterisk * represents a statistically significant difference at P <0.05.

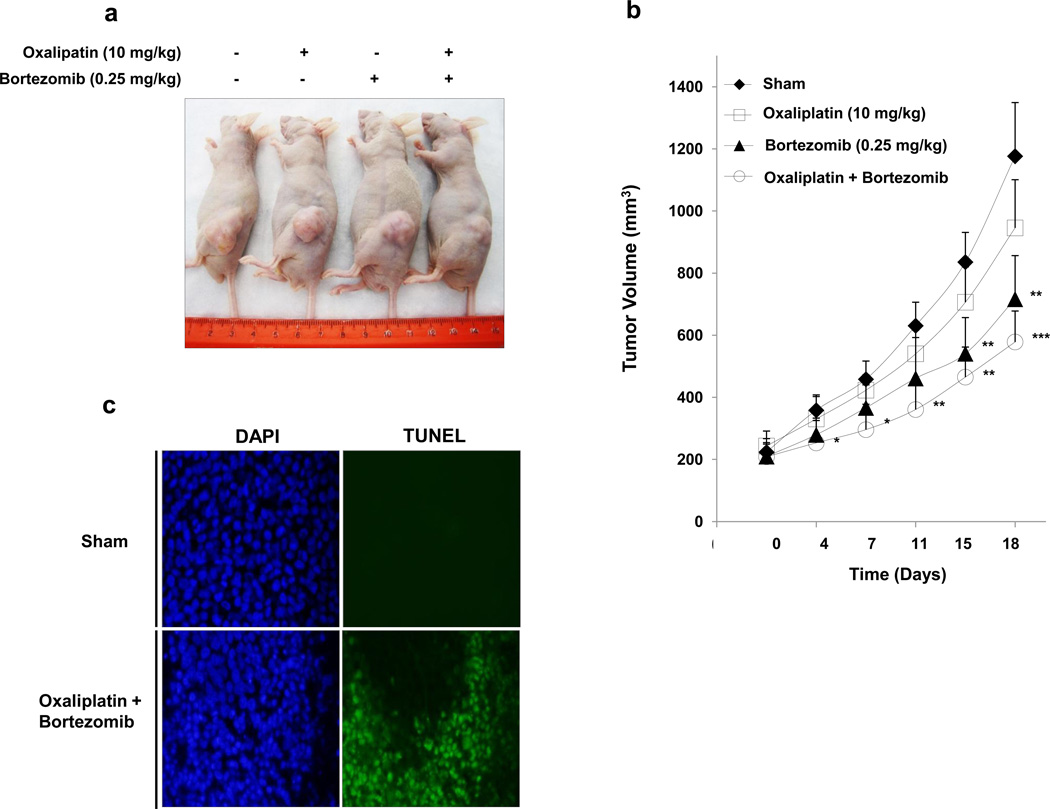

3.5. Effect of oxaliplatin and bortezomib on the growth of HCT116 xenograft tumors

We performed preclinical studies to examine the effect of the combinatorial treatment on growth of xenograft tumors (Fig. 6a). Figure 6b, based on data from 18 days after treatment, shows the effect of oxaliplatin alone on tumor growth compared to the sham group; there was only a slight, not statistically significant, difference. Bortezomib alone caused a statistically significant decrease of tumor growth (p < 0.01). Moreover, oxaliplatin combined with bortezomib caused a significant decrease of HCT116 tumor growth compared with the sham group (p < 0.001) and single treatment groups. TUNEL assay confirmed more apoptotic deaths in xenograft tumor tissue at day 18 after oxaliplatin in combination with bortezomib treatment in comparison to sham group (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6. Effect of oxaliplatin/bortezomib on the growth of HCT116 xenograft.

NU/NU mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 1 × 106 tumor cells per mouse, and the tumors were allowed to grow to 200 mm3. A total of 10 mg/kg oxaliplatin and/or 0.25 mg/kg bortezomib was administered by intraperitoneal injection, respectively. (a) Photograph of representative tumor bearing mouse from each group 18 days after drug administration. (b) Tumor growth curve. Error bars represent SD from 5 mice. *, **, or ***, statistically significant difference compared with the control group at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, or P < 0.001 respectively. (c) Tumor tissues were harvested at day 18 after drug administration and subjected to TUNEL assay to detect apoptosis. Cell nuclei were stained with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Representative images are shown.

4. Discussion

Several conclusions can be drawn upon consideration of the data presented here. First, a combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib synergistically induces apoptosis. Second, the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway plays an important role in the apoptosis through activating the mitochondria-dependent pathway. Third, Beclin-1 is dissociated from Bcl-xL and initiates autophagy during the treatment. However, Beclin-1 is subsequently cleaved by activated caspase 8 and the cleavage of Beclin-1 results in the suppression of autophagy and enhancement of apoptosis. Finally, the combinatorial treatment significantly inhibits colorectal cancer xenografts’ tumor growth.

Apoptosis and autophagy are two evolutionarily conserved processes that maintain homeostasis during stress. Although the two pathways utilize fundamentally distinct machinery, apoptosis and autophagy are highly interconnected and share many key regulators. In this study, we observed that Bcl-xL and Beclin-1 are regulators controlling a crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib.

We previously reported that Bcl-xL, a key antiapoptotic molecule, undergoes phosphorylation in response to treatment with oxaliplatin in combination with mapatumumab and hyperthermia [25, 39]. Bcl-xL phosphorylation requires activated JNK, which can recognize a proline residue on the carboxyl side of the phospho-acceptor [40]. Some studies reported phosphorylation to occur on serine 62, while others reported it to occur on threonines 47 and 115 [41, 42]. This study with site-directed mutagenesis at Ser-62 showed that cells expressing a validated phospho-defective Bcl-xL mutant are resistant to the combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib-induced apoptosis, whereas cells expressing a phospho-mimic Bcl-xL are sensitive to the combinatorial treatment-induced apoptosis, indicating that phosphorylation at Ser-62 is a key regulatory mechanism for antagonizing anti-apoptotic function in the combinatorial treatment.

Previous studies have shown that Bcl-2/Bcl-xL phosphorylation may not only be a mechanism for regulating apoptosis and a mechanism for regulating autophagy, but perhaps also a mechanism for regulating the switch between the two pathways [31, 43, 44]. JNK has been found to be able to trigger autophagy by targeting Bcl-2/Bcl-xL proteins and abrogating their binding to Beclin-1 [34, 35]; JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 at residues T69, S70, and S87 is required for dissociation of Bcl-2 from Beclin-1 and autophagy activation [45]. Unlike Bcl-2, data from Figure 5d suggests that for Bcl-xL, phosphorylation only at residue S62 may be sufficient for Bcl-xL dissociation from Beclin-1. Death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) has been found to act similarly to JNK, being able to phosphorylate Beclin-1 which results in dissociation of Beclin-1 from Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and induction of autophagy [46, 47].

During initiation of autophagosome formation, after release from Bcl-2/Bcl-xL, Beclin-1 functions as a platform by binding to class III PI3K/vacuolar protein sorting-34 (Vps34), UV-resistance-associated gene (UVRAG), activating molecule in Beclin-1-regulated autophagy (AMBRA-1), and/or Beclin-1-associated autophagy related key regulator (Barkor) to assemble the class III PI3K complex [49–52]. Beclin-1 is the mammalian homolog of yeast Atg6. It contains a conserved BH3 domain, which is both necessary and sufficient for its interaction with Bcl-xL [48]. The amphipathic BH3 helix of Beclin-1 binds to a conserved hydrophobic groove of Bcl-xL. Previous studies have shown that binding of Beclin-1 to Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibits the autophagic function of Beclin-1, suggesting that Beclin-1 might have a role in the convergence between autophagy and apoptotic cell death [38, 48, 53]. During treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib, dissociation of Beclin-1 from Bcl-xL triggers autophagy, however, activated caspase 8 cleaves Beclin-1 at TDVD133 and DQLD149 and subsequently suppresses autophagy (Fig. 5e, ref. 8, 38). The C-terminal fragment of Beclin-1-C is known to localize predominantly at the mitochondria and release cytochrome c and HtrA2/Omi which facilitates apoptosis [37].

Our data illustrate that a combinatorial treatment of oxaliplatin and bortezomib synergistically induces apoptosis and effectively activates the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway by activating the JNK-Bcl-xL-Bax pathway. Moreover, our data suggest that Beclin-1 is dissociated from phosphorylated Bcl-xL and initiates autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib. However, activated caspase 8 probably cleaves Beclin-1 and suppresses Beclin-1-associated autophagy and enhances apoptosis. The studies presented here further elucidate the Bcl-xL/Beclin-1-mediated crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy during treatment with oxaliplatin and bortezomib. A greater understanding of Bcl-xL/Beclin-1-mediated pathways may be critical for enhancing the chemotherapeutic efficacy of oxaliplatin and bortezomib.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grant: NCI grant R01CA140554 (Y.J.L.), R01CA106348 (L.Z.) and R01CA121105 (L.Z.) This project used the UPCI Core Facility and was supported in part by award P30CA047904.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- JNK

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- Bcl-xL

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- BAX

Bcl-2–associated X protein

- PARP

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- BH3

Bcl-2 homology domain 3

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: SYK, YJL. Development of methodology: SYK, YJL. Acquisition of data: SYK, XS. Analysis and interpretation data: SYK, YJL. Writing, review and/or revision of the manuscript: SYK, YJL. Administrative, technical or material support: LZ. Study supervision: YJL. Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Martenson JA. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothenberg ML, Meropol NJ, Poplin EA, Van Cutsem E, Wadler S. Mortality associated with irinotecan plus bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin: summary findings of an independent panel. J Clin Oncol. 2001;18:3801–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, DiPaola RS, Lotze MT, White E. Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:654–666. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N, Karantza V. Autophagy as a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:157–168. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.14622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters JP, Pober JS, Bradley JR. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. J Pathol. 2013;230:241–248. doi: 10.1002/path.4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, Yu H, Qin H, Kang J, Yu C, Zhong J, Su J, Li H, Sun L. Inhibition of autophagy enhances cisplatin cytotoxicity through endoplasmic reticulum stress in human cervicalcancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;314:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djavaheri-Mergny M, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. Cross talk between apoptosis and autophagy by caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin 1. Oncogene. 2010;29:1717–1719. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou W, Han J, Lu C, Goldstein LA, Rabinowich H. Autophagic degradation of active caspase-8: A crosstalk mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2010;6:891–900. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteve JM, Knecht E. Mechanisms of autophagy and apoptosis: Recent developments in breast cancer cells. World J Biol Chem. 2011;2:232–238. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v2.i10.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gozuacik D, Kimchi A. Autophagy as a cell death and tumor suppressor mechanism. Oncogene. 2004;23:2891–2906. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein A, Arnold D. Oxaliplatin: a review of approved uses. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:125–137. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.643870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arango D, Wilson AJ, Shi Q, Corner GA, Arañes MJ, Nicholas C, Lesser M, Mariadason JM, Augenlicht LH. Molecular mechanisms of action and prediction of response to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Brit J Cancer. 2004;91:1931–1946. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nannizzi S, Veal GJ, Giovannetti E, Mey V, Ricciardi S, Ottley CJ, Del Tacca M, Danesi R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for the synergistic cytotoxicity elicited by oxaliplatin and pemetrexed in colon cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:547–558. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyle S, Maraveyas A. Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Dig Surg. 2005;22:401–414. doi: 10.1159/000091441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Cutsem E, Nordlinger B, Cervantes A On behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Advanced colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for treatment. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(Supplement 5):v93–v97. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajkumar SV, Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Proteasome inhibition as a novel therapeutic target in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;3:630–639. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selimovic D, Porzig BB, El-Khattouti A, Badura HE, Ahmad M, Ghanjati F, Santourlidis S, Haikel Y, Hassan M. Bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor triggers both apoptosis and autophagy-dependent pathways in melanoma cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson PG, Mitsiades C, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib: proteasome inhibition as an effective anticancer therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:33–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.042905.122625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suh KS, Goy A. Bortezomib in mantle cell lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2008;2:149–168. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia L, Gopinathan G, Sukumar JT, Gribben JG. Blocking Autophagy Prevents Bortezomib-Induced NF-κB Activation by Reducing I-κBα Degradation in Lymphoma Cells. PLos One. 2012;7:e32584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill DS, Martin S, Armstrong JL, Flockhart R, Tonison JJ, Simpson DG, Birch-Machin MA, Redfern CP, Lovat PE. Combining the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress - Inducing Agents Bortezomib and Fenretinide as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1192–1198. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song X, Kim SY, Lee YJ. Evidence for two modes of synergistic induction of apoptosis by mapatumumab and oxaliplatin in combination with hyperthermia in human colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song X, Kim SY, Lee YJ. The role of Bcl-xL in synergistic induction of apoptosis by mapatumumab and oxaliplatin in combination with hyperthermia on human colon cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1567–1579. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0209-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo J, Lee YJ. Effect of hyperthermia and chemotherapeutic agents on TRAIL-induced cell death in human colon cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:98–109. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labussiere M, Pinel S, Delfortrie S, Plenat F, Chastagner P. Proteasome inhibition by bortezomib does not translate into efficacy on two malignant glioma xenografts. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:1283–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell RA, Sanchez E, Steinberg J, Shalitin D, Li ZW, Chen H, Berenson JR. Vorinostat enhances the antimyeloma effects of melphalan and bortezomib. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Upreti M, Galitovskaya EN, Chu R, Tackett AJ, Terrano AJ, Terrano DT, Granell S, Chambers TC. Identification of the major phosphorylation site in Bcl-xL induced by microtubule inhibitors and analysis of its functional significance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35517–35525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordy C, He YW. The crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: where does this lead? Protein Cell. 2012;3:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou F, Yang Y, Xing D. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL play important roles in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. FEBS J. 2011;278:403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oberstein A, Jeffrey PD, Shi Y. Crystal structure of the Bcl-XL-Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3-only protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13123–13132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinha S, Levine B. The autophagy effector Beclin 1: a novel BH3-only protein. Oncogene. 2008;27:S137–S148. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Beclin-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:330–335. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirawan E, Vande Walle L, Kersse K, Cornelis S, Claerhout S, Vanoverberghe I, Roelandt R, De Rycke R, Verspurten J, Declercq W, Agostinis P, Vanden Berghe T, Lippens S, Vandenabeele P. Caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 inactivates Beclin-1-induced autophagy and enhances apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e18. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Wang P, Sun Q, Ding WX, Yin XM, Sobol RW, Stolz DB, Yu J, Zhang L. Following cytochrome c release, autophagy is inhibited during chemotherapy-induced apoptosis by caspase 8-mediated cleavage of Beclin 1. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3625–3634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song X, Kim SY, Lee YJ. Evidence for Two Modes of Synergistic Induction of Apoptosis by Mapatumumab and Oxaliplatin in Combination with Hyperthermia in Human Colon Cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ubersax JA, Ferrell JE., Jr Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:530–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basu A, Haldar S. Identification of a novel Bcl-xL phosphorylation site regulating the sensitivity of taxol- or 2-methoxyestradiol-induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2003;538:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharbanda S, Saxena S, Yoshida K, Pandey P, Kaneki M, Wang Q, Cheng K, Chen YN, Campbell A, Sudha T, Yuan ZM, Narula J, Weichselbaum R, Nalin C, Kufe D. Translocation of SAPK/JNK to mitochondria and interaction with Bcl-x(L) in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:322–327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei Y, Sinha S, Levine B. Dual role of JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in autophagy and apoptosis regulation. Autophagy. 2008;4:949–951. doi: 10.4161/auto.6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He W, Wang Q, Srinivasan B, Xu J, Padilla MT, Li Z, Wang X, Liu Y, Gou X, Shen HM, Xing C, Lin Y. A JNK-mediated autophagy pathway that triggers c-IAP degradation and necroptosis for anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell. 2008;30:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Eisenstein M, Kimchi A. Phosphorylation of Beclin 1 by DAP-kinase promotes autophagy by weakening its interactions with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. Autophagy. 2009;5:720–722. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Mizrachy L, Idelchuk Y, Koren I, Eisenstein M, et al. DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:285–292. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oberstein A, Jeffrey PD, Shi Y. Crystal structure of the Bcl-XL-Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3-only protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13123–13132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, Giunta L, Di Bartolomeo S, Nardacci R, Corazzari M, Fuoco C, Ucar A, Schwartz P, Gruss P, Piacentini M, Chowdhury K, Cecconi F. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447:1121–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, Jung JU. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–699. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furuya N, Yu J, Byfield M, Pattingre S, Levine B. The evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin 1 is required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor suppressor function. Autophagy. 2005;1:46–52. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Q, Fan W, Chen K, Ding X, Chen S, Zhong Q. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19211–19216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhai D, Jin C, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Comparison of chemical inhibitors of antiapoptotic Bcl-2-family proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1419–1421. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]