Abstract

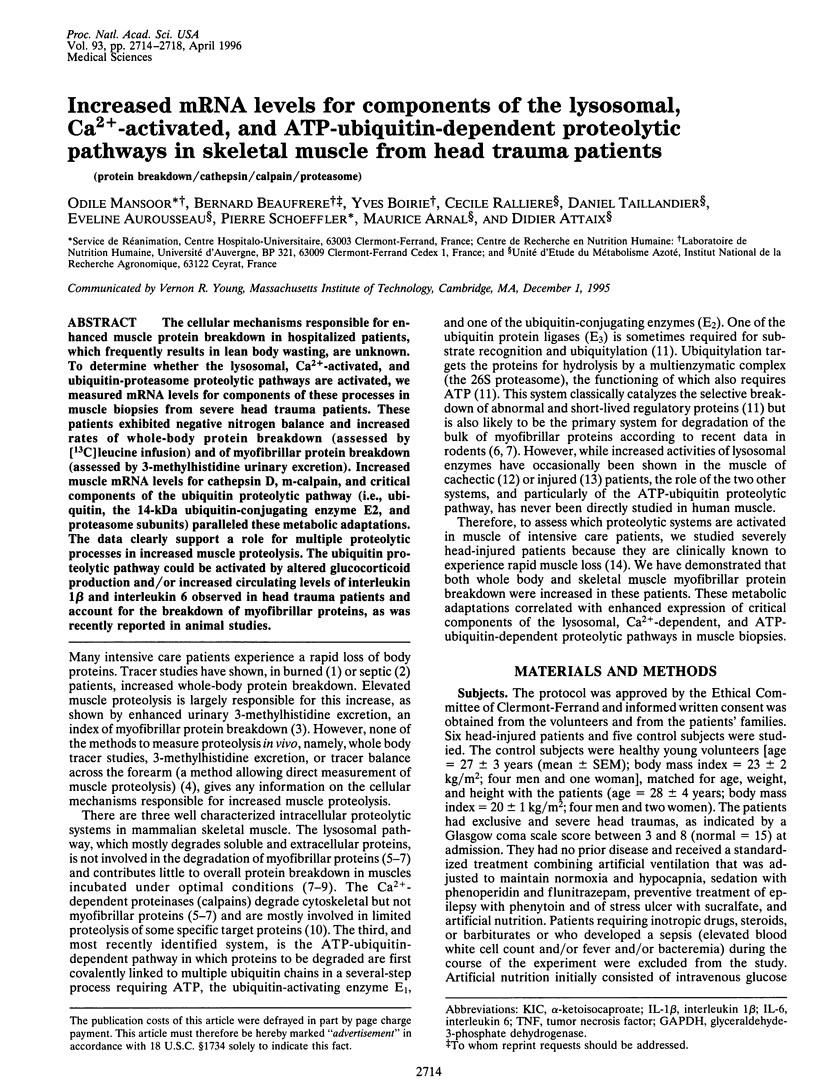

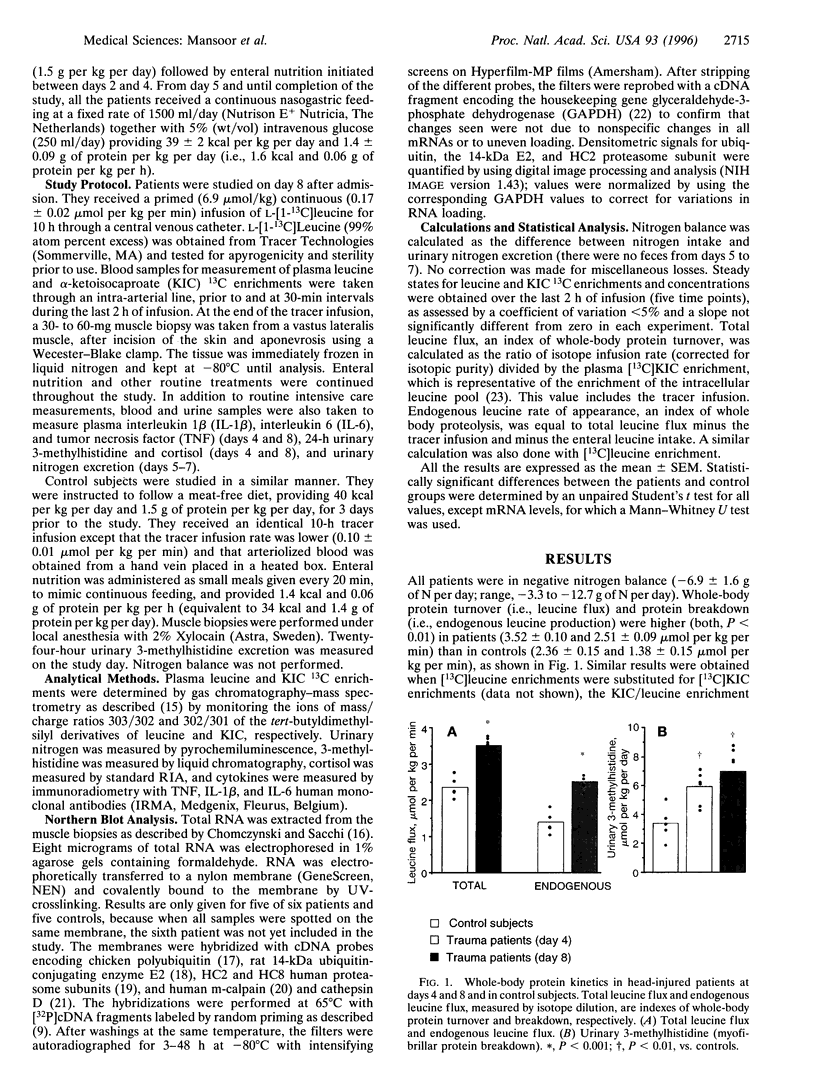

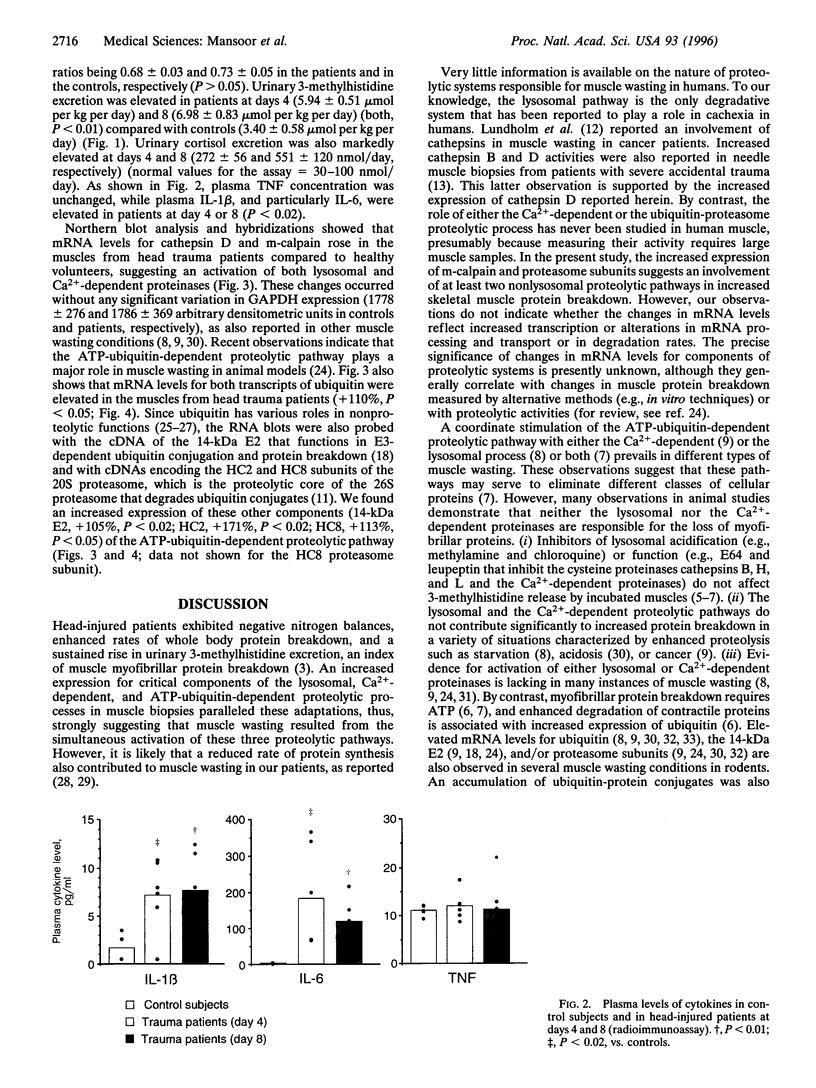

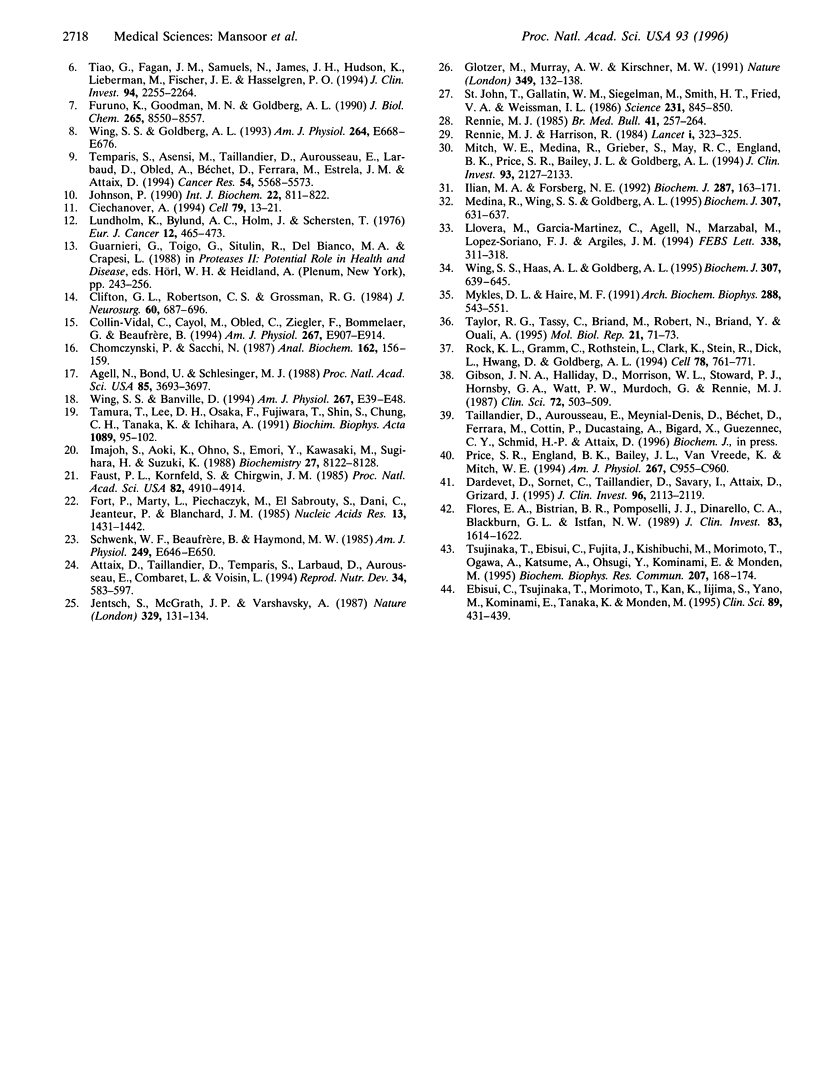

The cellular mechanisms responsible for enhanced muscle protein breakdown in hospitalized patients, which frequently results in lean body wasting, are unknown. To determine whether the lysosomal, Ca2+-activated, and ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathways are activated, we measured mRNA levels for components of these processes in muscle biopsies from severe head trauma patients. These patients exhibited negative nitrogen balance and increased rates of whole-body protein breakdown (assessed by [13C]leucine infusion) and of myofibrillar protein breakdown (assessed by 3-methylhistidine urinary excretion). Increased muscle mRNA levels for cathepsin D, m-calpain, and critical components of the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway (i.e., ubiquitin, the 14-kDa ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, and proteasome subunits) paralleled these metabolic adaptations. The data clearly support a role for multiple proteolytic processes in increased muscle proteolysis. The ubiquitin proteolytic pathway could be activated by altered glucocorticoid production and/or increased circulating levels of interleukin 1beta and interleukin 6 observed in head trauma patients and account for the breakdown of myofibrillar proteins, as was recently reported in animal studies.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Agell N., Bond U., Schlesinger M. J. In vitro proteolytic processing of a diubiquitin and a truncated diubiquitin formed from in vitro-generated mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jun;85(11):3693–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaix D., Taillandier D., Temparis S., Larbaud D., Aurousseau E., Combaret L., Voisin L. Regulation of ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in muscle wasting. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1994;34(6):583–597. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19940605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. J., Gelfand R. A. The in vivo study of cardiac and skeletal muscle protein turnover. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1989 Mar;5(2):133–148. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610050204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1994 Oct 7;79(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton G. L., Robertson C. S., Grossman R. G., Hodge S., Foltz R., Garza C. The metabolic response to severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1984 Apr;60(4):687–696. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.4.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vidal C., Cayol M., Obled C., Ziegler F., Bommelaer G., Beaufrere B. Leucine kinetics are different during feeding with whole protein or oligopeptides. Am J Physiol. 1994 Dec;267(6 Pt 1):E907–E914. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.6.E907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardevet D., Sornet C., Taillandier D., Savary I., Attaix D., Grizard J. Sensitivity and protein turnover response to glucocorticoids are different in skeletal muscle from adult and old rats. Lack of regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway in aging. J Clin Invest. 1995 Nov;96(5):2113–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI118264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisui C., Tsujinaka T., Morimoto T., Kan K., Iijima S., Yano M., Kominami E., Tanaka K., Monden M. Interleukin-6 induces proteolysis by activating intracellular proteases (cathepsins B and L, proteasome) in C2C12 myotubes. Clin Sci (Lond) 1995 Oct;89(4):431–439. doi: 10.1042/cs0890431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust P. L., Kornfeld S., Chirgwin J. M. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for human cathepsin D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Aug;82(15):4910–4914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E. A., Bistrian B. R., Pomposelli J. J., Dinarello C. A., Blackburn G. L., Istfan N. W. Infusion of tumor necrosis factor/cachectin promotes muscle catabolism in the rat. A synergistic effect with interleukin 1. J Clin Invest. 1989 May;83(5):1614–1622. doi: 10.1172/JCI114059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort P., Marty L., Piechaczyk M., el Sabrouty S., Dani C., Jeanteur P., Blanchard J. M. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985 Mar 11;13(5):1431–1442. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno K., Goodman M. N., Goldberg A. L. Role of different proteolytic systems in the degradation of muscle proteins during denervation atrophy. J Biol Chem. 1990 May 25;265(15):8550–8557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J. N., Halliday D., Morrison W. L., Stoward P. J., Hornsby G. A., Watt P. W., Murdoch G., Rennie M. J. Decrease in human quadriceps muscle protein turnover consequent upon leg immobilization. Clin Sci (Lond) 1987 Apr;72(4):503–509. doi: 10.1042/cs0720503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M., Murray A. W., Kirschner M. W. Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature. 1991 Jan 10;349(6305):132–138. doi: 10.1038/349132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri G., Toigo G., Situlin R., Del Bianco M. A., Crapesi L. Cathepsin B and D activity in human skeletal muscle in disease states. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;240:243–256. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1057-0_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian M. A., Forsberg N. E. Gene expression of calpains and their specific endogenous inhibitor, calpastatin, in skeletal muscle of fed and fasted rabbits. Biochem J. 1992 Oct 1;287(Pt 1):163–171. doi: 10.1042/bj2870163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imajoh S., Aoki K., Ohno S., Emori Y., Kawasaki H., Sugihara H., Suzuki K. Molecular cloning of the cDNA for the large subunit of the high-Ca2+-requiring form of human Ca2+-activated neutral protease. Biochemistry. 1988 Oct 18;27(21):8122–8128. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch S., McGrath J. P., Varshavsky A. The yeast DNA repair gene RAD6 encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Nature. 1987 Sep 10;329(6135):131–134. doi: 10.1038/329131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. Calpains (intracellular calcium-activated cysteine proteinases): structure-activity relationships and involvement in normal and abnormal cellular metabolism. Int J Biochem. 1990;22(8):811–822. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(90)90284-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovera M., García-Martínez C., Agell N., Marzábal M., López-Soriano F. J., Argilés J. M. Ubiquitin gene expression is increased in skeletal muscle of tumour-bearing rats. FEBS Lett. 1994 Feb 7;338(3):311–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell B. B., Ruderman N. B., Goodman M. N. Evidence that lysosomes are not involved in the degradation of myofibrillar proteins in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 1986 Feb 15;234(1):237–240. doi: 10.1042/bj2340237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm K., Bylund A. C., Holm J., Scherstén T. Skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with malignant tumor. Eur J Cancer. 1976 Jun;12(6):465–473. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(76)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina R., Wing S. S., Goldberg A. L. Increase in levels of polyubiquitin and proteasome mRNA in skeletal muscle during starvation and denervation atrophy. Biochem J. 1995 May 1;307(Pt 3):631–637. doi: 10.1042/bj3070631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitch W. E., Medina R., Grieber S., May R. C., England B. K., Price S. R., Bailey J. L., Goldberg A. L. Metabolic acidosis stimulates muscle protein degradation by activating the adenosine triphosphate-dependent pathway involving ubiquitin and proteasomes. J Clin Invest. 1994 May;93(5):2127–2133. doi: 10.1172/JCI117208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykles D. L., Haire M. F. Sodium dodecyl sulfate and heat induce two distinct forms of lobster muscle multicatalytic proteinase: the heat-activated form degrades myofibrillar proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991 Aug 1;288(2):543–551. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price S. R., England B. K., Bailey J. L., Van Vreede K., Mitch W. E. Acidosis and glucocorticoids concomitantly increase ubiquitin and proteasome subunit mRNAs in rat muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994 Oct;267(4 Pt 1):C955–C960. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.4.C955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie M. J., Harrison R. Effects of injury, disease, and malnutrition on protein metabolism in man. Unanswered questions. Lancet. 1984 Feb 11;1(8372):323–325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie M. J. Muscle protein turnover and the wasting due to injury and disease. Br Med Bull. 1985 Jul;41(3):257–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock K. L., Gramm C., Rothstein L., Clark K., Stein R., Dick L., Hwang D., Goldberg A. L. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994 Sep 9;78(5):761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk W. F., Beaufrere B., Haymond M. W. Use of reciprocal pool specific activities to model leucine metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol. 1985 Dec;249(6 Pt 1):E646–E650. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1985.249.6.E646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. H., Wildbore M., Wolfe R. R. Whole body protein kinetics in severely septic patients. The response to glucose infusion and total parenteral nutrition. Ann Surg. 1987 Mar;205(3):288–294. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198703000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John T., Gallatin W. M., Siegelman M., Smith H. T., Fried V. A., Weissman I. L. Expression cloning of a lymphocyte homing receptor cDNA: ubiquitin is the reactive species. Science. 1986 Feb 21;231(4740):845–850. doi: 10.1126/science.3003914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T., Lee D. H., Osaka F., Fujiwara T., Shin S., Chung C. H., Tanaka K., Ichihara A. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of cDNAs for five major subunits of human proteasomes (multi-catalytic proteinase complexes). Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991 May 2;1089(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. G., Tassy C., Briand M., Robert N., Briand Y., Ouali A. Proteolytic activity of proteasome on myofibrillar structures. Mol Biol Rep. 1995;21(1):71–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00990974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temparis S., Asensi M., Taillandier D., Aurousseau E., Larbaud D., Obled A., Béchet D., Ferrara M., Estrela J. M., Attaix D. Increased ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in skeletal muscles of tumor-bearing rats. Cancer Res. 1994 Nov 1;54(21):5568–5573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiao G., Fagan J. M., Samuels N., James J. H., Hudson K., Lieberman M., Fischer J. E., Hasselgren P. O. Sepsis stimulates nonlysosomal, energy-dependent proteolysis and increases ubiquitin mRNA levels in rat skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest. 1994 Dec;94(6):2255–2264. doi: 10.1172/JCI117588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka T., Ebisui C., Fujita J., Kishibuchi M., Morimoto T., Ogawa A., Katsume A., Ohsugi Y., Kominami E., Monden M. Muscle undergoes atrophy in association with increase of lysosomal cathepsin activity in interleukin-6 transgenic mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Feb 6;207(1):168–174. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. S., Banville D. 14-kDa ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme: structure of the rat gene and regulation upon fasting and by insulin. Am J Physiol. 1994 Jul;267(1 Pt 1):E39–E48. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.1.E39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. S., Goldberg A. L. Glucocorticoids activate the ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system in skeletal muscle during fasting. Am J Physiol. 1993 Apr;264(4 Pt 1):E668–E676. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.4.E668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. S., Haas A. L., Goldberg A. L. Increase in ubiquitin-protein conjugates concomitant with the increase in proteolysis in rat skeletal muscle during starvation and atrophy denervation. Biochem J. 1995 May 1;307(Pt 3):639–645. doi: 10.1042/bj3070639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe R. R., Goodenough R. D., Burke J. F., Wolfe M. H. Response of protein and urea kinetics in burn patients to different levels of protein intake. Ann Surg. 1983 Feb;197(2):163–171. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198302000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young V. R., Munro H. N. Ntau-methylhistidine (3-methylhistidine) and muscle protein turnover: an overview. Fed Proc. 1978 Jul;37(9):2291–2300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]