Abstract

To further understanding of the genetic basis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) susceptibility, we aggregated published meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) including 26,488 cases and 83,964 controls of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry. We observed significant excess in directional consistency of T2D risk alleles across ancestry groups, even at SNPs demonstrating only weak evidence of association. By following up the strongest signals of association from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis in an additional 21,491 cases and 55,647 controls of European ancestry, we identified seven novel T2D susceptibility loci. Furthermore, we observed considerable improvements in fine-mapping resolution of common variant association signals at several T2D susceptibility loci. These observations highlight the benefits of trans-ethnic GWAS for the discovery and characterisation of complex trait loci, and emphasize an exciting opportunity to extend insight into the genetic architecture and pathogenesis of human diseases across populations of diverse ancestry.

The majority of GWAS of T2D susceptibility have been undertaken in populations of European ancestry1–5, predominantly because of existing infrastructure, sample availability, and relatively poor coverage by many of the earliest genome-wide genotyping arrays of common genetic variation in other major ethnic groups6. However, European ancestry populations constitute only a subset of human genetic variation, and thus are insufficient to fully characterise T2D risk variants in other ethnic groups. Furthermore, the latest genome-wide genotyping arrays are less biased towards Europeans, and more recent T2D GWAS have been performed, with great success, in populations from other ancestry groups, including East Asians7–12, South Asians13,14, Mexicans and Mexican Americans15, and African Americans16. These studies have provided initial evidence of overlap in T2D susceptibility loci between ancestry groups and for coincident risk alleles at lead SNPs across diverse populations17,18. These observations are consistent with a model in which the underlying causal variants at many of these loci are shared across ancestry groups, and thus arose prior to human population migration out of Africa. Under such a model, we would expect to improve power to detect novel susceptibility loci for the disease, and enhance fine-mapping resolution of causal variants, by combining GWAS across ancestry groups through trans-ethnic meta-analysis, because of increased sample size and differences in the structure of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between such diverse populations6,19–21.

In this study, we aggregated published meta-analyses of GWAS in a total of 26,488 cases and 83,964 controls from populations of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry5,11,13,15. T2D GWAS from populations of African ancestry, which would be expected to provide the greatest potential for fine-mapping of common causal variants due to less extensive LD than other ethnic groups6, were not accessible for inclusion in our analyses. With these data, we aimed to: (i) assess the evidence for excess concordance in the direction of effect of T2D risk alleles across ancestry groups; (ii) identify novel T2D susceptibility loci through trans-ethnic meta-analysis and subsequent validation in an additional 21,491 cases and 55,647 controls of European ancestry; and (iii) evaluate the improvements in the fine-mapping resolution of common variant association signals in established T2D susceptibility loci through trans-ethnic meta-analysis, despite the lack of GWAS from populations of African ancestry.

RESULTS

We considered published meta-analyses of GWAS of T2D susceptibility from four major ethnic groups (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), undertaken by: (i) the DIAbetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium5 (European ancestry; 12,171 cases and 56,862 controls); (ii) the Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network T2D (AGEN-T2D) Consortium11 (East Asian ancestry; 6,952 cases and 11,865 controls); (iii) the South Asian T2D (SAT2D) Consortium13 (South Asian ancestry; 5,561 cases and 14,458 controls); and (iv) the Mexican American T2D (MAT2D) Consortium15 (Mexican and Mexican American ancestry; 1,804 cases and 779 controls). We obtained association summary statistics from the four available ethnic-specific meta-analyses, each imputed at up to 2.5 million autosomal SNPs from Phase II/III HapMap22,23 to provide a uniform catalogue of common genetic variation, defined by minor allele frequency (MAF) of at least 5%, across ancestry groups (Online Methods). These association summary statistics were then combined across ancestry groups via trans-ethnic fixed-effects meta-analysis (Online Methods).

Directional consistency of T2D risk alleles across ancestry groups

We began by evaluating heterogeneity in allelic effects (i.e. discordance in the direction and/or magnitude of odds-ratios) between ancestry groups at 69 established autosomal T2D susceptibility loci. We assessed the evidence for heterogeneity at previously reported lead SNPs on the basis of Cochran’s Q-statistic from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 3). We observed nominal evidence of heterogeneity (Bonferroni correction, pQ<0.05/69=0.00072) at the previously reported lead SNP at just three loci. At TCF7L2 (rs7903146, pQ=0.00055), the odds-ratio is largest in European ancestry populations, although the risk allele has a consistent direction of effect across ethnicities. At PEPD (rs3786897, pQ=0.00055) and KLF14 (rs13233731, pQ=0.00064), however, the association signals are apparently specific to East Asian and European ancestry populations, respectively, despite the fact that the reported lead SNPs are common in all ethnic groups. We also observed that, at 52 previously reported lead SNPs passing quality control in each of the four ethnic-specific meta-analyses, 34 showed the same direction of effect across all ancestry groups (65.4%, compared with 12.5% expected by chance, binomial test p<2.2×10−16). The strong evidence of homogeneity in allelic effects across ancestry groups at the majority of previously reported lead SNPs argues against the “synthetic association” hypothesis24. It is improbable that GWAS signals at most established T2D susceptibility loci reflect unobserved lower frequency causal alleles with larger effects because: (i) rare variants are unlikely to have arisen before human population migration out of Africa and thus are not expected to be widely shared across diverse populations25; and (ii) patterns of LD with these variants are anticipated to be highly variable between ethnicities.

To gain insights into the potential for the discovery of novel T2D susceptibility loci through fixed-effects trans-ethnic meta-analysis, we next assessed the genome-wide coincidence of risk alleles (i.e. direction of effect) across ancestry groups after exclusion of the 69 established autosomal GWAS signals, defined as mapping within 500kb of the previously reported lead SNPs (Online Methods). First, we identified independent SNPs (separated by at least 500kb) with nominal evidence of association (p≤0.001) with T2D from the European ancestry meta-analysis. By aligning the effect of the T2D risk allele from the European meta-analysis into the other ancestry groups, we observed evidence of significant excess in directional concordance between ethnicities: 57.0% with East Asian populations (binomial test p=0.0077); 55.4% with South Asian populations (binomial test p=0.032); and 56.6% with Mexican and Mexican American populations (binomial test p=0.010). Using the same approach, we also observed excess consistency in the direction of effect between ethnicities at independent SNPs demonstrating weaker evidence of T2D association (0.001<p≤0.01) from the European meta-analysis (Table 1). In contrast, when we considered independent SNPs with no evidence of association (p>0.5) with T2D, there was no enrichment in coincident risk alleles across ethnic groups. We repeated this analysis by identifying T2D risk alleles at SNPs with nominal evidence of association in East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American meta-analyses, in turn, and assessing concordance in the direction of effect in each of the other ancestry groups (Supplementary Table 4). The evidence for an excess in concordance between T2D risk alleles across ethnicities was not as strong, particularly for the Mexican and Mexican American meta-analysis. However, this presumably reflects reduced power due to smaller sample sizes, and there was still significant over representation of alleles with the same direction of effect across ancestry groups at SNPs with nominal evidence of association with the disease.

Table 1.

Concordance in the direction of effect of T2D risk alleles identified in a meta-analysis of GWAS of European ancestry (12,171 cases and 56,862 controls) with those from meta-analyses of GWAS of East Asian (6,952 cases and 11,865 controls), South Asian (5,561 cases and 14,458 controls), and Mexican and Mexican American (1,804 cases and 779 controls) ancestry, after exclusion of the 69 established autosomal susceptibility loci, defined as mapping within 500kb of the previously reported lead SNP.

| European ancestry meta-analysis p-value threshold | Trans-ethnic concordance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European into East Asian | European into South Asian | European into Mexican and Mexican American | |||||||

| Concordant SNPs/Total SNPs | % | Binomial test p-value | Concordant SNPs/Total SNPs | % | Binomial test p-value | Concordant SNPs/Total SNPs | % | Binomial test p-value | |

| p≤0.001 | 180/316 | 57.0 | 0.0077 | 175/316 | 55.4 | 0.032 | 179/316 | 56.6 | 0.010 |

| 0.001<p≤0.01 | 877/1624 | 54.0 | 0.00068 | 861/1624 | 53.0 | 0.0080 | 886/1624 | 54.6 | 0.00013 |

| 0.01<p≤0.5 | 2556/5053 | 50.6 | 0.21 | 2604/5053 | 51.5 | 0.015 | 2588/5053 | 51.2 | 0.043 |

| 0.5<p≤1 | 2535/5039 | 50.3 | 0.34 | 2532/5039 | 50.2 | 0.37 | 2519/5039 | 50.0 | 0.51 |

Seven novel T2D susceptibility loci achieving genome-wide significance

The observations from our concordance analyses are consistent with a long tail of common T2D susceptibility variants, with effects which are decreasing in magnitude, but which are homogeneous across ancestry groups. Under such a model, we would expect these variants to be amenable to discovery via trans-ethnic fixed-effects meta-analyses. In this study, by aggregating the published ethnic-specific meta-analyses under a fixed-effects model, we identified 33 independent SNPs (separated by at least 500kb) with suggestive evidence of association (p<10−5) at loci not previously reported for T2D susceptibility in any ancestry group (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Figure 1). By convention, we have labelled loci according to the gene nearest to the lead SNP, unless a compelling biological candidate mapped nearby. It is essential to validate partially imputed association signals with direct genotyping. Consequently, we carried forward these 33 loci for in silico follow-up in a meta-analysis of an additional 21,491 T2D cases and 55,647 controls of European ancestry5, genotyped with the Metabochip (Online Methods, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). This custom array was designed to facilitate cost-effective replication of nominal associations for T2D and other metabolic and cardiovascular traits26. However, it provides relatively limited coverage of common genetic variation, genome-wide, with the result that the lead SNPs, or close proxies (CEU r2>0.6 from Phase II HapMap), were present at just 24 of the loci. We also identified poorer proxies at two additional loci, rs9505118 (SSR1/RREB1, CEU r2=0.26, p=1.9×10−6) and rs4275659 (MPHOSPH9, CEU r2=0.48, p=5.5×10−6), which, nonetheless, demonstrated only marginally weaker association signals than the lead SNPs (SSR1/RREB1, rs9502570, p=5.7×10−7; MPHOSPH9, rs1727313, p=1.2×10−6). Given that these variants met our threshold for follow-up from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis, they were also considered for validation.

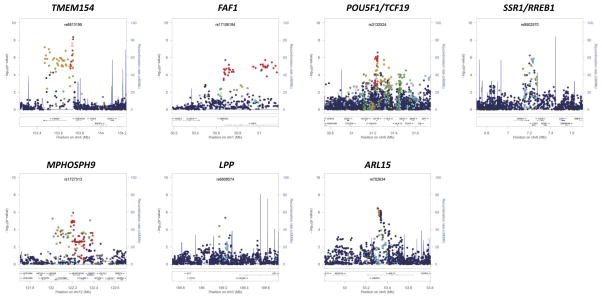

By combining association summary statistics from the trans-ethnic “discovery” and European ancestry “validation” meta-analyses, SNPs achieved genome-wide significance (combined meta-analysis p<5×10−8) at seven loci (Table 2, Figure 1). We observed no evidence of heterogeneity in allelic effects between discovery and validation stages of the combined meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 5). As expected, the novel loci are characterised by lead SNPs that are relatively common in all ethnicities, and have modest effects on T2D susceptibility which are homogeneous across ancestry groups (Supplementary Table 6). Adjustments for covariates were not harmonised within or between consortia because of variation in individual study design and recorded non-genetic risk factors. However, we observed no evidence of heterogeneity in allelic effects in the European ancestry validation meta-analysis after stratification of studies according to covariate adjustment (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 7). These data thus provide no evidence of bias in allelic effect estimates at lead SNPs at the novel loci, and suggest our results to be robust to variability in correction for potential confounders across studies.

Table 2.

Novel T2D susceptibility loci achieving genome-wide significance (p<5×10−8), identified through trans-ethnic “discovery” GWAS meta-analysis of 26,488 cases and 83,964 controls of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry, with follow-up in a “validation” meta-analysis of an additional 21,491 cases and 55,647 controls of European ancestry, genotyped with the Metabochip.

| Locus | Lead SNP | Chr | Build 36 position (bp) | Allelesa | Trans-ethnic “discovery” meta-analysis | European ancestry “validation” meta-analysis | Combined meta-analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Other | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| TMEM154 | rs6813195 | 4 | 153,739,925 | C | T | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 4.2×10−9 | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 2.0×10−6 | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | 4.1×10−14 |

| SSR1/RREB1 | rs9505118 | 6 | 7,235,436 | A | G | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | 1.9×10−6 | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 1.7×10−4 | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 1.4×10−9 |

| FAF1 | rs17106184 | 1 | 50,682,573 | G | A | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | 1.9×10−6 | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | 4.8×10−4 | 1.10 (1.07–1.14) | 4.1×10−9 |

| POU5F1/TCF19 | rs3130501 | 6 | 31,244,432 | G | A | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | 1.5×10−6 | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | 7.0×10−4 | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | 4.2×10−9 |

| LPP | rs6808574 | 3 | 189,223,217 | C | T | 1.08 (1.04–1.11) | 4.3×10−6 | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 2.6×10−4 | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | 5.8×10−9 |

| ARL15 | rs702634 | 5 | 53,307,177 | A | G | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 3.4×10−7 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 2.1×10−3 | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | 6.9×10−9 |

| MPHOSPH9 | rs4275659 | 12 | 122,013,881 | C | T | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 5.5×10−6 | 1.06 (1.02–1.09) | 4.4×10−4 | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 9.5×10−9 |

Chr: chromosome. OR: odds-ratio. CI: confidence interval.

Alleles are aligned to the forward strand of NCBI Build 36.

Figure 1. Signal plots of the trans-ethnic “discovery” GWAS meta-analysis for novel T2D susceptibility loci.

The trans-ethnic meta-analysis comprises 26,488 T2D cases and 83,964 controls from populations of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry, imputed up to 2.5 million Phase II/III HapMap autosomal SNPs. Each point represents a SNP passing quality control in the trans-ethnic meta-analysis, plotted with their p-value (on a −log10 scale) as a function of genomic position (NCBI Build 36). In each panel, the lead SNP is represented by the purple symbol. The colour coding of all other SNPs indicates LD with the lead SNP (estimated by CEU r2 from Phase II HapMap): red r2≥0.8; gold 0.6≤r2<0.8; green 0.4≤r2<0.6; cyan 0.2≤r2<0.4; blue r2<0.2; grey r2 unknown. The shape of the plotting symbol corresponds to the annotation of the SNP: upward triangle for framestop or splice; downward triangle for non-synonymous; square for synonymous or UTR; and circle for intronic or non-coding. Recombination rates are estimated from Phase II HapMap and gene annotations are taken from the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser.

The novel loci include SNPs mapping near POU5F1/TCF19 in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a region of the genome that is essential to immune response. The MHC harbours HLA class II genes, which together account for approximately half the genetic risk to type 1 diabetes (T1D)27. We observed no evidence of association of T2D with tags for traditional T1D HLA risk alleles in the trans-ethnic meta-analysis: HLA-DR4 (rs660895, p=0.32) and HLA-DR3 (rs2187668, p=0.34). Furthermore, when we considered lead SNPs at 49 T1D susceptibility loci (Supplementary Table 8), we observed nominal evidence of association (p<0.05) with T2D, with the same risk allele for both diseases, at just two (GLIS3 and 6q22.32), but not at that mapping to the MHC (rs9268645, p=0.33). There is very strong evidence that T1D-risk variants, particularly in the MHC, are also associated with latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA)28,29, a late-age onset, more indolent form of the disease, which often results in a clinical misdiagnosis of T2D. Although studies contributing to the trans-ethnic meta-analysis differed in the degree to which they were able to exclude LADA cases, the lack of association of T1D-risk variants suggests that rates of diagnostic misclassification of autoimmune diabetes were too modest to drive the T2D GWAS signal at the POU5F1/TCF19 locus.

The novel loci also include SNPs mapping to ARL15 and SSR1/RREB1, which have been previously implicated, at genome-wide significance, in regulation of fasting insulin (FI) and fasting glucose (FG), respectively30. The lead SNPs for T2D (rs702634) and FI (rs4865796) mapping to ARL15 are closely correlated in European and East Asian ancestry populations (CEU r2=1.00 and CHB+JPT r2=0.87 from Phase II HapMap). However, the lead T2D SNP (rs9505118) is independent of that for FG (rs17762454) at the SSR1/RREB1 locus (CEU and CHB+JPT r2<0.05). The ARL15 locus has also been associated with circulating adiponectin levels, an adipocyte-secreted protein that has anti-diabetic effects31, but the lead SNP (rs4311394) is independent of that for T2D susceptibility from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis.

To obtain a more comprehensive view of the overlap of novel T2D susceptibility loci with metabolic phenotypes, we interrogated published European ancestry meta-analyses from the Meta-Analysis of Glycaemic and Insulin-related Consortium (MAGIC) Investigators3,30, the Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium32,33 and the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium34, to evaluate the effect of T2D risk alleles on: glycaemic traits, including homeostatic model of assessment indices of beta-cell function (HOMA-B) and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR); anthropometric measures; and plasma lipid concentrations (Online Methods, Supplementary Tables 9, 10 and 11). T2D risk alleles at SSR1/RREB1 and LPP have features that indicate a primary role on susceptibility through beta-cell dysfunction: increased FG (p=1.0×10−5 and p=8.6×10−7, respectively), and reduced HOMA-B (p=0.11 and p=0.011, respectively). Conversely, the T2D risk allele mapping to ARL15 is associated with increased FI, most strongly after adjustment for body-mass index (BMI) (p=5.0×10−12), and increased HOMA-IR (p=0.021), and is thus more characteristic of action through insulin resistance. This risk allele is also associated with reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (p=0.022) and increased triglycerides (p=0.010), as expected, but also with reduced BMI (p=5.6×10−5).

To identify the most promising functional candidate transcripts amongst those mapping to the novel susceptibility loci, we interrogated public databases and unpublished resources for expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) from a variety of tissues (Online Methods). The lead T2D SNPs at three loci showed nominal association (p<10−5) with expression, and were in strong LD (CEU and CHB+JPT r2>0.8) with the reported cis-eQTL variant: SSR1 (B cells, p=2.2×10−6) at the SSR1/RREB1 locus; ABCB9 (liver, p=7.4×10−12) and SETD8 (lung, p<2.0×10−16) at the MPHOSPH9 locus; and HCG27 (monocytes, p=1.3×10−69) at the POU5F1/TCF19 locus (Supplementary Table 12).

We also evaluated novel loci for potential functional mechanisms underlying T2D susceptibility (Online Methods). We identified variants in pilot data from the 1000 Genomes Project25 that are in strong LD (CEU and CHB+JPT r2>0.8) with the lead SNPs in the seven novel susceptibility loci for functional annotation. We identified a missense variant at the POU5F1/TCF19 locus in TCF19 (rs113581344, V211M; CEU r2=0.96 and CHB+JPT r2=0.80 with lead SNP rs3130501), although it is predicted to be tolerated by SIFT35 (Supplementary Table 13). Lead SNPs in the novel susceptibility loci were also in strong LD with variants in the untranslated regions of SSR1 (at the SSR1/RREB1 locus) and ABCB9, OGFOD2, and PITPNM2 (at the MPHOSPH9 locus). Variants in strong LD with the lead SNPs at two of the novel susceptibility loci overlap regions of predicted regulatory function generated by the ENCODE Project36 (Supplementary Figure 2). The lead SNP at the LPP locus maps to an enhancer region which is active in HepG2 cells. We also identified a variant at the FAF1 locus (rs58836765; CEU r2=0.89 and CHB+JPT r2=0.80 with lead SNP rs17106184) which overlaps a region of open chromatin activity in pancreatic islets and other cell types. This open chromatin site is in a region correlated with expression of ELAVL4, which has been demonstrated to regulate insulin translation in pancreatic beta cells37, highlighting this transcript as a credible candidate at the FAF1 locus. Regulatory annotations in HepG2 cells and pancreatic islets are both broadly enriched at T2D associated variants38, and are thus supportive of these functional mechanisms for causal variant activity at both loci.

Improved fine-mapping resolution at T2D susceptibility loci

Given our observation that the causal variants underlying GWAS signals are shared across ancestry groups at many T2D susceptibility loci, we evaluated the evidence for improved fine-mapping resolution through trans-ethnic meta-analysis. For this purpose, we combined association summary statistics from the ethnic-specific meta-analyses using MANTRA39. This Bayesian approach has the advantage of allowing for heterogeneity in allelic odds-ratios between ancestry groups, arising as a result of differential patterns of LD with a shared underlying causal variant across diverse populations, which cannot be accommodated in fixed-effects meta-analysis (Online Methods). Simulation studies have demonstrated improved detection and localisation of causal variants through trans-ethnic meta-analysis with MANTRA compared to either a fixed- or random-effects model39,40.

Within each locus, we constructed “credible sets”41 of SNPs that are most likely to be causal based on their statistical evidence of association from the MANTRA meta-analysis. Credible sets can be interpreted in a similar way to confidence intervals in a frequentist statistical framework. For example, assuming that a locus harbours a single causal variant that is reported in the meta-analysis, the probability that it will be contained in the 99% credible set is 0.99. Smaller credible sets, in terms of the number of SNPs they contain, or the genomic interval they cover, thus correspond to fine-mapping at higher resolution. It is essential that SNP coverage is as uniform as possible across studies in the construction of credible sets. Otherwise, differences in association signals between variants may reflect variability in sample sizes in the meta-analysis, and not true differences in magnitude of effects on T2D susceptibility. Consequently, we have not considered the European ancestry Metabochip validation studies in our fine-mapping analyses because SNP density on the array is too sparse, across the majority of T2D susceptibility loci, to allow high-quality imputation up to the Phase II/III HapMap reference panels utilised in the trans-ethnic discovery GWAS.

In constructing credible sets, we assume that there is a single causal variant at each locus. However, there is increasing evidence that multiple association signals, typically characterised by independent common “index” SNPs, are relatively widespread at T2D susceptibility loci, for example CDKN2A/B and KCNQ16. Fine-mapping of these independent association signals will require formal conditioning, adjusting for genotypes at each index SNP in turn, before construction of the credible set for each underlying causal variant. Approximate conditioning, without formal computation, as implemented in GCTA42, makes use of meta-analysis summary statistics and a reference panel to approximate LD between SNPs (and hence correlation between parameter estimates in a joint association model). Unfortunately, this approach is not feasible in a trans-ethnic context because of differences in LD structure between ancestry groups, and thus could not be applied in this study. Consequently, the credible sets defined here correspond to fine-mapping across association signals at each locus.

To assess the improvements in fine-mapping resolution by combining GWAS from diverse populations, we compared the properties of the MANTRA 99% credible set on the basis of association summary statistics from: (i) the European ancestry only meta-analysis; and (ii) the trans-ethnic meta-analysis of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry groups. We focussed on ten autosomal loci (of the 69 previously established) that attained association with T2D susceptibility at genome-wide significance in the European ancestry meta-analysis (Table 3). We did not consider loci with weaker signals of association since they were typically characterised by large 99% credible sets in the European ancestry meta-analysis, and thus might provide an over-estimate of the improvement in fine-mapping resolution by combining GWAS across ancestry groups. Of the loci considered, only at MTNR1B, did we not see any improvement in fine-mapping resolution, in terms of the number of SNPs and the genomic interval covered by the 99% credible set after trans-ethnic meta-analysis.

Table 3.

Properties of the 99% credible set of SNPs at ten established T2D susceptibility loci on the basis of association summary statistics from: (i) the meta-analysis of European ancestry GWAS only (12,171 cases and 56,862 controls); and (ii) the trans-ethnic meta-analysis of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry GWAS (26,488 cases and 83,964 controls).

| Locus | Chr | 99% credible set: European ancestry meta-analysis | 99% credible set: trans-ethnic meta-analysis | 99% credible set: reduction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | Interval (bp) | Build 36 location (bp) | SNPs | Interval (bp) | Build 36 location (bp) | SNPs | Interval (bp) | ||

| JAZF1 | 7 | 9 | 75,685 | 28,147,081–28,222,765 | 4 | 15,667 | 28,147,081–28,162,747 | 5 | 60,018 |

| SLC30A8 | 8 | 4 | 35,488 | 118,253,964–118,289,451 | 2 | 243 | 118,253,964–118,254,206 | 2 | 35,245 |

| CDKAL1 | 6 | 5 | 24,244 | 20,787,688–20,811,931 | 2 | 1,549 | 20,794,552–20,796,100 | 3 | 22,695 |

| HHEX/IDE | 10 | 8 | 19,195 | 94,452,862–94,472,056 | 2 | 937 | 94,455,539–94,456,475 | 6 | 18,258 |

| TCF7L2 | 10 | 3 | 13,684 | 114,744,078–114,757,761 | 2 | 2,309 | 114,746,031–114,748,339 | 1 | 11,375 |

| IGF2BP2 | 3 | 17 | 32,656 | 186,980,329–187,012,984 | 12 | 24,504 | 186,988,481–187,012,984 | 5 | 8,152 |

| FTO | 16 | 27 | 45,981 | 52,357,008–52,402,988 | 10 | 39,335 | 52,361,075–52,400,409 | 17 | 6,646 |

| CDKN2A/B | 9 | 3 | 2,019 | 22,122,076–22,124,094 | 1 | 1 | 22,122,076–22,122,076 | 2 | 2,018 |

| PPARG | 3 | 23 | 265,269 | 12,106,687–12,371,955 | 21 | 265,269 | 12,106,687–12,371,955 | 2 | 0 |

| MTNR1B | 11 | 15 | 55,032 | 92,307,378–92,362,409 | 15 | 55,032 | 92,307,378–92,362,409 | 0 | 0 |

Chr: chromosome. SNPs: number of SNPs.

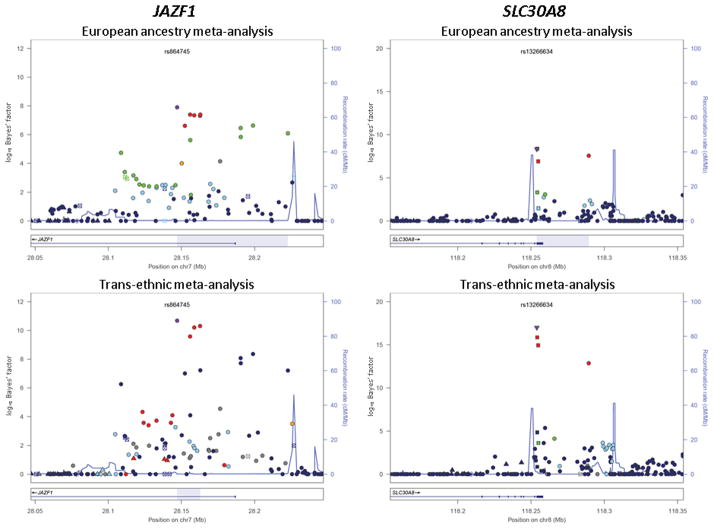

The greatest enhancement in fine-mapping resolution after trans-ethnic meta-analysis was observed at the JAZF1 locus, where the genomic interval covered by the 99% credible set was reduced from 76kb to just 16kb (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 3). Of the nine variants in the European 99% credible set, five were excluded after trans-ethnic meta-analysis because of low LD with the lead SNP at this locus in East Asian ancestry populations (CHB+JPT r2<0.05 with rs864745). Amongst the variants retained in the 99% credible set after trans-ethnic meta-analysis, interrogation of predicted regulatory function from the ENCODE Project36 revealed that rs1635852 maps to a region of open chromatin with enhancer activity, bound by several transcription factors. This SNP has been previously shown to have allelic differences in pancreatic islet enhancer activity43, and is also correlated with expression of CREB5, highlighting this transcript as a credible candidate at the JAZF1 locus.

Figure 2. Signal plots presenting 99% credible sets of SNPs at the JAZF1 and SLC30A8 loci.

The credible sets were constructed on the basis of: (i) the meta-analysis of European ancestry GWAS only (12,171 cases and 56,862 controls); and (ii) the trans-ethnic meta-analysis of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry GWAS (26,488 cases and 83,964 controls). In each panel, each point represents a SNP passing quality control in the MANTRA analysis, plotted with their Bayes’ factor (on a log10 scale) as a function of genomic position (NCBI Build 36). The lead SNP is represented by the purple symbol. The colour coding of all other SNPs indicates LD with the lead SNP (estimated by Phase II HapMap CEU r2 for the European ancestry meta-analysis and CHB+JPT for the trans-ethnic meta-analysis to highlight differences in structure between ancestry groups): red r2≥0.8; gold 0.6≤r2<0.8; green 0.4≤r2<0.6; cyan 0.2≤r2<0.4; blue r2<0.2; grey r2 unknown. The shape of the plotting symbol corresponds to the annotation of the SNP: upward triangle for framestop or splice; downward triangle for non-synonymous; square for synonymous or UTR; and circle for intronic or non-coding. Recombination rates are estimated from Phase II HapMap and gene annotations are taken from the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser. The genomic region covered by the 99% credible set is highlighted in grey.

We also observed a substantial reduction in the genomic interval covered by the credible set at the SLC30A8 locus (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 3), from 35kb (four SNPs) on the basis of only European ancestry GWAS, to less than 1kb (two SNPs) after trans-ethnic meta-analysis. However, the lead SNP is strongly correlated with all variants in the credible set before trans-ethnic meta-analysis in both European and East Asian ancestry groups (CEU and CHB+JPT r2≥0.8 with rs13266634), suggesting that the improved fine-mapping resolution at this locus is more likely due to increased sample size than differences in LD structure between the populations. Encouragingly, the lead SNP after trans-ethnic meta-analysis is more clearly separated from others in the credible set, and is a non-synonymous variant, R325W, which plays an established functional role in T2D susceptibility44.

Finally, we tested variants present in the 99% credible sets at the ten loci, on the basis of only the European ancestry GWAS and the trans-ethnic meta-analysis, for enrichment of functional annotation compared to randomly shifted element locations (Online Methods). Variants in the trans-ethnic 99% credible sets were significantly enriched (empirical p<0.05) for overlap with DNaseI hypersensitive sites (DHS p=0.038) and transcription factor binding sites (TFBS p=0.0060). However, no such enrichment in either annotation category was observed for the European ancestry 99% credible sets (DHS p=0.18; TFBS p=0.087). These data suggest that variants retained after trans-ethnic meta-analysis show greater potential for functional impact on T2D susceptibility through these regulatory mechanisms.

The fine-mapping intervals defined by credible sets after trans-ethnic meta-analysis are limited by the density and allele frequency spectrum of the GWAS genotyping arrays and HapMap reference panels used for imputation. Although these reference panels provide comprehensive coverage of common SNPs (MAF>5%) across ancestry groups, imputation up to phased haplotypes from the 1000 Genomes Project25,45, for example, would allow assessment of the impact of lower frequency variation on T2D susceptibility in diverse populations46–48. However, we have demonstrated that, for a fixed reference panel, trans-ethnic meta-analysis can improve localisation of common causal SNPs within established T2D susceptibility loci, and have identified highly annotated variants within fine-mapping intervals defined by the 99% credible sets. We have also assessed the sensitivity of the trans-ethnic fine-mapping analysis to genotype quality at directly typed or imputed SNPs (Supplementary Table 14). We repeated MANTRA fine-mapping with subsets of SNPs that pass quality control in at least 80% (N=88,361) or 90% (N=99,406) of individuals from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis. As the threshold for reported sample size increased, the number of SNPs included in the fine-mapping analysis was reduced, but the genomic intervals covered by the 99% credible sets remained unchanged, suggesting resolution to be relatively robust to genotype quality at common variants.

DISCUSSION

We have identified seven novel loci for T2D susceptibility at genome-wide significance by combining GWAS from multiple ancestry groups. Our study has provided evidence of many more common variant loci, not yet reaching genome-wide significance, which contribute to the “missing heritability” of T2D susceptibility, in agreement with polygenic analyses in European ancestry GWAS5,49. The effects of these common variants are modest, but homogeneous across ancestry groups, and thus would be amenable to discovery through trans-ethnic meta-analysis in larger samples. We have also demonstrated improvements in the resolution of fine-mapping of common variant association signals through trans-ethnic meta-analysis, even in the absence of GWAS of African ancestry, which would be expected to better refine localisation due to reduced LD in these populations. Future releases of reference panels from the 1000 Genomes Project are anticipated to include 2,500 samples, including haplotypes of South Asian ancestry and wider representation of African descent populations. This panel will provide a comprehensive catalogue of genetic variation with MAF as low as 0.5%, as well as many rarer variants, across major ancestry groups, thus facilitating imputation and coverage of loci for future trans-ethnic fine-mapping efforts.

Our analyses clearly highlight the benefits of combining GWAS from multiple ancestry groups for discovery and characterisation of common variant loci contributing to complex traits, and emphasise an exciting opportunity to further our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying human diseases across populations from diverse ethnicities.

ONLINE METHODS

Ancestry-specific GWAS meta-analyses

Ancestry-specific meta-analyses have been previously performed by: the DIAGRAM Consortium (12,171 cases and 56,862 controls, European ancestry)5; the AGEN-T2D Consortium (6,952 cases and 11,865 controls, East Asian ancestry)11; the SAT2D Consortium (5,561 cases and 14,458 controls, South Asian ancestry)13; and the MAT2D Consortium (1,804 cases and 779 controls, Mexican and Mexican American ancestry)15. Further details of the samples and methods employed within each ancestry group are presented in the corresponding consortium papers5,11,13,15. Briefly, individuals were assayed with a range of genotyping products, with sample and SNP quality control (QC) undertaken within each individual study (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Each GWAS scaffold was imputed up to 2.5 million autosomal SNPs using reference panels from Phase II/III HapMap22,23 (Supplementary Table 2). Each SNP with MAF>1%, (except MAF>5% in the Mexican and Mexican American ancestry GWAS due to smaller sample size), and passing QC, was tested for association with T2D under an additive model after adjustment for study-specific covariates (Supplementary Table 2). Covariate adjustments were not harmonised within or between consortia because of variation in individual study design and recorded non-genetic risk factors. The results of each GWAS were corrected for population structure with genomic control50 (unless λGC<1). Association summary statistics from GWAS within each ancestry group were then combined via fixed-effects meta-analysis. The results of each ancestry meta-analysis were then corrected by a second round of genomic control: European ancestry (λGC=1.10); East Asian ancestry (λGC=1.05); South Asian ancestry (λGC=1.02); Mexican and Mexican American ancestry (λGC=1.01).

Trans-ethnic “discovery” GWAS meta-analysis

Association summary statistics from each ancestry-specific meta-analysis were combined via fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis(in a total of 26,488 cases and 83,964 controls). The association results of the trans-ethnic meta-analysis were corrected by genomic control50 (λGC=1.05).

Heterogeneity analyses

For each previously reported lead SNP at an established T2D susceptibility locus, we assessed heterogeneity in allelic effects between the ethnic-specific meta-analyses by means of Cochran’s Q-statistic51 (Supplementary Table 3). Amongst the 52 SNPs passing QC in all four ethnic-specific meta-analyses, we identified those that showed the same direction of effect across all ancestry groups, and evaluated the significance of the excess in concordance (12.5% expected) with a one-sided binomial test.

Concordance analyses

We identified SNPs passing QC and with MAF>1% in all four ethnic-specific meta-analyses. We excluded variants in the 69 established autosomal T2D susceptibility loci, defined as 500kb up- and down-stream of the previously reported lead SNPs. We also excluded AT/GC SNPs to eliminate bias due to strand misalignment between ethnic-specific meta-analyses. Amongst the remaining SNPs, we selected an independent subset with nominal evidence of association (p≤0.001) with T2D from the European ancestry meta-analysis, separated by at least 500kb. For each independent SNP, we identified the T2D risk allele from the European ancestry meta-analysis and determined the direction of effect in the East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry meta-analyses. We calculated the proportion of these SNPs that had the same direction of effect for the European ancestry risk allele and the significance of the excess in concordance (50% expected) with a one-sided binomial test. We repeated this analysis for SNPs with weaker evidence of association with T2D from the European ancestry meta-analysis: 0.001<p≤0.01; 0.01<p≤0.5; and 0.5<p≤1 (Table 1). Finally, we repeated these analyses, using the East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry meta-analyses, in turn, to identify subsets of independent T2D risk alleles, and assessed concordance into the other ethnic groups (Supplementary Table 4).

European ancestry “validation” meta-analysis

The previously published validation meta-analysis consisted of 21,491 cases and 55,647 controls of European ancestry from the DIAGRAM Consortium5, all genotyped with the Metabochip26 (Supplementary Table 1). We excluded the Pakistan Risk Of Myocardial Infarction Study (PROMIS) from the validation meta-analysis to avoid overlap with a subset of the same individuals contributing to the SAT2D Consortium meta-analysis13. Full details of the samples and methods employed in the validation meta-analysis are presented in the DIAGRAM Consortium paper5. Briefly, sample and SNP QC were undertaken within each study (Supplementary Table 2). Each high-quality SNP (MAF>1%) was tested for association with T2D under an additive model after adjustment for study-specific covariates (Supplementary Table 2). Association summary statistics for each study were corrected using the genomic control inflation factor obtained from a subset of 3,598 “QT interval” replication SNPs5,26 (unless λQT<1). These statistics were then combined via fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis, and were corrected by a second round of genomic control (λQT=1.19).

Combined meta-analysis

We selected lead SNPs at 33 novel loci with suggestive evidence of association (p<10−5) from the trans-ethnic “discovery” GWAS meta-analysis for in silico follow-up in the European ancestry “validation” meta-analysis. Of these, 16 SNPs were genotyped directly on Metabochip, and 10 more had a proxy (CEU and CHB+JPT HapMap r2≥0.2). For these 26 SNPs, association summary statistics from the discovery and validation meta-analyses were combined via fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 5). The combined meta-analysis consisted of 47,979 T2D cases and 139,611 controls. Heterogeneity in allelic effects between the two stages of the combined meta-analysis was assessed by means of Cochran’s Q-statistic51.

Sensitivity to covariate adjustment

We identified 19 studies (11,327 cases and 31,342 controls) from the European ancestry “validation” meta-analysis that adjusted for only age, sex (unless male- or female-specific), and population structure, where necessary (Supplementary Table 2): AMC-PAS; BHS; DILGOM; EAS; EGCUT; EMIL-ULM; EPIC; FUSION Stage 2; D2D2007; Dr’s Extra; HUNT; METSIM (male-specific); HNR, IMPROVE; KORAGen Stage 2; PIVUS; THISEAS; ULSAM (male-specific); and WARREN2. Association summary statistics from each of these studies were then combined via fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis, the results of which were subsequently corrected for genomic control (λQT=1.12). The remaining six studies (10,164 cases and 24,305 controls) did not adjust for age and/or sex, or included additional covariates to account for BMI or cardiovascular-related disease status (Supplementary Table 2): deCODE Stage 2; DUNDEE; GMetS; PMB; SCARFSHEEP; and STR. Association summary statistics from each of these studies were then combined via fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis, but did not require subsequent correction for genomic control (λQT=1.00). We then tested for heterogeneity in allelic effects between these two sets of studies by means of Cochran’s Q-statistic51 (Supplementary Table 7).

Association of lead T1D SNPs with T2D

We obtained association summary statistics with T2D from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis for previously reported lead SNPs in established T1D susceptibility loci27 (Supplementary Table 8). For each SNP, we aligned the allelic effect on T2D according to the risk allele for T1D (where reported). We also obtained association summary statistics for tags for T1D HLA risk alleles: HLA-DR4 (rs660895) and HLA-DR3 (rs2187668).

Association of lead T2D SNPs with metabolic traits

We obtained association summary statistics (p-values, directed Z-scores and/or allelic effects and corresponding standard errors) for lead SNPs at novel T2D susceptibility loci in published European ancestry GWAS meta-analyses of metabolic phenotypes: glycaemic traits3,30, anthropometric measures32,33, and plasma lipid concentrations34. We considered glycaemic traits in non-diabetic individuals from the MAGIC Investigators (Supplementary Table 9). For FG and FI concentrations (with and without adjustment for BMI), the meta-analysis consisted of up to 133,010 and 108,557 individuals, respectively. For HOMA-B and HOMA-IR, the meta-analysis consisted of up to 37,037 individuals. We considered anthropometric measures from the GIANT Consortium (Supplementary Table 10). For BMI and waist-hip ratio adjusted for BMI, the meta-analysis consisted of 123,865 and 77,167 individuals, respectively. Finally, we considered plasma lipid concentrations from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium (Supplementary Table 11). For total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides, the meta-analysis consisted of up to 100,184 individuals.

Expression analyses

We interrogated public databases and unpublished resources for cis-eQTL expression with lead SNPs in the novel susceptibility loci in multiple tissues. Details of these resources are summarised in the Supplementary Note. The collated results from these resources met study-specific criteria for statistical significance for association with expression. For each transcript associated with the lead T2D SNP (Supplementary Table 12), we identified the cis-eQTL SNP with the strongest association with expression in the same tissue, and subsequently estimated the LD between them, using pilot data from the 1000 Genomes Project25 (CEU and CHB+JPT) to assess coincidence of the signals.

Functional annotation

We identified variants in pilot data from the 1000 Genomes Project25 that are in strong LD (CEU and CHB+JPT r2>0.8) with the lead SNPs in the novel susceptibility loci for functional annotation. Identified non-synonymous variants were interrogated for likely downstream functional consequences using SIFT35 (Supplementary Table 13). Variants were also assessed for overlap with regions of predicted regulatory function generated by the ENCODE Project36 including: ChromHMM regulatory state definitions from 9 cell lines (GM12878, HepG2, HUVEC, HMEC, HSMM, K562, NHLF, NHEK, and hESC); transcription factor binding ChIP sites from 95 cell types; open chromatin (DNaseI hypersensitivity) sites from 125 cell types; transcripts correlated with open chromatin site activity; and sequence motifs from JASPAR, TRANSFAC and de novo prediction (Supplementary Figure 2).

Fine-mapping analyses

We used MANTRA39 to fine-map T2D susceptibility loci on the basis of association summary statistics from: (i) the meta-analysis of European ancestry GWAS only5; and (ii) the trans-ethnic meta-analysis of European, East Asian, South Asian, and Mexican and Mexican American ancestry GWAS5,11,13,15. MANTRA allows for trans-ethnic heterogeneity in allelic effects, arising as a result of differences in the structure of LD with the causal variant in diverse populations, by assigning ancestry groups to “clusters” according to a Bayesian partition model of relatedness between them, defined by pair-wise genome-wide mean allele frequency differences (Supplementary Figure 4). Evidence in favour of association of each SNP with T2D is measured by a Bayes’ factor (BF). We assume a single causal variant for T2D at each locus (defined by the region 500kb up- and down-stream of the lead SNP from the trans-ethnic meta-analysis). We then calculated the posterior probability that the jth SNP is causal, amongst those reported in the meta-analysis, by:

In this expression, BFj denotes the BF in favour of association of the jth SNP, and the summation in the denominator is over all variants passing QC across the locus41. A 99% credible set of variants was then constructed by: (i) ranking all SNPs according to their BF; and (ii) combining ranked SNPs until their cumulative posterior probability exceeds 0.99.

SNPs in the 99% credible sets were assessed for enrichment in ChromHMM regulatory state (enhancer, promoter and insulator), DNaseI hypersensitive and transcription factor binding sites, using data from the ENCODE Project36. We performed 1,000 permutations by shifting the location of the annotation sites a random distance within 100kb, and recalculated the overlap to obtain empirical p-values for enrichment in each annotation category.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for the research undertaken in this study has been received from: the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; the European Commission (ENGAGE FP7 HEALTH-F4-2007-201413); the Medical Research Council UK (G0601261); the Mexico Convocatoria (SSA/IMMS/ISSSTE-CONACYT 2012-2, clave 150352, IMSS R-2011-785-018 and CONACYT Salud-2007-C01-71068); the US National Institutes of Health (DK062370, HG000376, DK085584, DK085545, DK073541 and DK085501); and the Wellcome Trust (WT098017, WT090532, WT090367, WT098381, WT081682, and WT085475). We acknowledge the many colleagues who contributed to collection and phenotypic characterization of the clinical samples, and the genotyping and analysis of the GWAS data, full details of which are provided in the contributing consortia papers5,11,13,15. We also thank those individuals who agreed to participate in this study.

Anubha Mahajan1,220, Min Jin Go2,220, Weihua Zhang3,220, Jennifer E Below4,220, Kyle J Gaulton1,220, Teresa Ferreira1, Momoko Horikoshi1,5, Andrew D Johnson6, Maggie CY Ng7,8, Inga Prokopenko1,5,9, Danish Saleheen10,11, Xu Wang12, Eleftheria Zeggini13, Goncalo R Abecasis14, Linda S Adair15, Peter Almgren16, Mustafa Atalay17, Tin Aung18,19, Damiano Baldassarre20,21, Beverley Balkau22,23, Yuqian Bao24, Anthony H Barnett25,26, Ines Barroso13,27,28, Abdul Basit29, Latonya F Been30, John Beilby31,32,33, Graeme I Bell34,35, Rafn Benediktsson36,37, Richard N Bergman38, Bernhard O Boehm39,40, Eric Boerwinkle41,42, Lori L Bonnycastle43, Noël Burtt44, Qiuyin Cai45, Harry Campbell46,47, Jason Carey44, Stephane Cauchi48, Mark Caulfield49, Juliana CN Chan50, Li-Ching Chang51, Tien-Jyun Chang52, Yi-Cheng Chang52, Guillaume Charpentier53, Chien-Hsiun Chen51,54, Han Chen55, Yuan-Tsong Chen51, Kee-Seng Chia12,56, Manickam Chidambaram57, Peter S Chines43, Nam H Cho58, Young Min Cho59, Lee-Ming Chuang52,60, Francis S Collins43, Marilyn C Cornelis61, David J Couper62, Andrew T Crenshaw44, Rob M van Dam61,63, John Danesh10, Debashish Das64, Ulf de Faire65, George Dedoussis66, Panos Deloukas13, Antigone S Dimas1,67,68, Christian Dina69,70,71, Alex SF Doney72,73, Peter J Donnelly1,74, Mozhgan Dorkhan16, Cornelia van Duijn75,76, Josée Dupuis6,55, Sarah Edkins13, Paul Elliott3,77, Valur Emilsson78, Raimund Erbel79, Johan G Eriksson80,81,82,83, Jorge Escobedo84, Tonu Esko85,86,87,88, Elodie Eury48, Jose C Florez87,89,90,91, Pierre Fontanillas44, Nita G Forouhi92, Tom Forsen81,93, Caroline Fox6,94, Ross M Fraser46, Timothy M Frayling95, Philippe Froguel9,48, Philippe Frossard11, Yutang Gao96, Karl Gertow97,98, Christian Gieger99, Bruna Gigante65, Harald Grallert100,101,102,103, George B Grant44, Leif C Groop16, Christopher J Groves5, Elin Grundberg104, Candace Guiducci44, Anders Hamsten97,98, Bok-Ghee Han2, Kazuo Hara105, Neelam Hassanali5, Andrew T Hattersley106, Caroline Hayward47, Asa K Hedman1, Christian Herder107, Albert Hofman75, Oddgeir L Holmen108, Kees Hovingh109, Astradur B Hreidarsson37, Cheng Hu24, Frank B Hu61,110, Jennie Hui31,32,33,111, Steve E Humphries112, Sarah E Hunt13, David J Hunter61,110,113, Kristian Hveem108, Zafar I Hydrie29, Hiroshi Ikegami114, Thomas Illig100,115, Erik Ingelsson1,116, Muhammed Islam117, Bo Isomaa83,118, Anne U Jackson14, Tazeen Jafar117,119, Alan James31,120,121, Weiping Jia24, Karl-Heinz Jöckel122, Anna Jonsson16, Jeremy BM Jowett123, Takashi Kadowaki105, Hyun Min Kang14, Stavroula Kanoni13, Wen Hong L Kao124, Sekar Kathiresan44,90,125, Norihiro Kato126, Prasad Katulanda5,127, Sirkka M Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi128,129, Ann M Kelly25,26, Hassan Khan10, Kay-Tee Khaw10, Chiea-Chuen Khor18,56,130, Hyung-Lae Kim131, Sangsoo Kim132, Young Jin Kim2, Leena Kinnunen133, Norman Klopp100,115, Augustine Kong134, Eeva Korpi-Hyövälti135, Sudhir Kowlessur136, Peter Kraft61,113, Jasmina Kravic16, Malene M Kristensen123, S Krithika137, Ashish Kumar1, Jesus Kumate138, Johanna Kuusisto139, Soo Heon Kwak59, Markku Laakso139, Vasiliki Lagou1, Timo A Lakka17,140, Claudia Langenberg92, Cordelia Langford13, Robert Lawrence141, Karin Leander65, Jen-Mai Lee12, Nanette R Lee142, Man Li124, Xinzhong Li143, Yun Li144,145, Junbin Liang146, Samuel Liju57, Wei-Yen Lim56, Lars Lind147, Cecilia M Lindgren1,44, Eero Lindholm16, Ching-Ti Liu55, Jian Jun Liu130, Stéphane Lobbens48, Jirong Long45, Ruth JF Loos92,148,149,150, Wei Lu151, Jian’an Luan92, Valeriya Lyssenko16, Ronald CW Ma50, Shiro Maeda60, Reedik Mägi85, Satu Männistö80, David R Matthews5, James B Meigs89,152, Olle Melander16, Andres Metspalu85,86, Julia Meyer99, Ghazala Mirza1, Evelin Mihailov85, Susanne Moebus122, Viswanathan Mohan57,153, Karen L Mohlke144, Andrew D Morris72,73, Thomas W Mühleisen154,155, Martina Müller-Nurasyid99,156,157, Bill Musk31,111,121,158, Jiro Nakamura159, Eitaro Nakashima159,160, Pau Navarro47, Peng-Keat Ng12, Alexandra C Nica67, Peter M Nilsson16, Inger Njølstad161, Markus M Nöthen154,155, Keizo Ohnaka162, Twee Hee Ong12, Katharine R Owen5,163, Colin NA Palmer72,73, James S Pankow164, Kyong Soo Park59,165, Melissa Parkin44, Sonali Pechlivanis122, Nancy L Pedersen166, Leena Peltonen13,44,80,167,219, John RB Perry1,95, Annette Peters168, Janani M Pinidiyapathirage169, Carl GP Platou108,170, Simon Potter13, Jackie F Price46, Lu Qi61,110, Venkatesan Radha57, Loukianos Rallidis171, Asif Rasheed11, Wolfgang Rathmann172, Rainer Rauramaa140,173, Soumya Raychaudhuri44,174,175, N William Rayner1,5, Simon D Rees25,26, Emil Rehnberg166, Samuli Ripatti13,80,167, Neil Robertson1,5, Michael Roden107,176,177, Elizabeth J Rossin44,87,178,179, Igor Rudan46, Denis Rybin180, Timo E Saaristo181,182, Veikko Salomaa80, Juha Saltevo183, Maria Samuel11, Dharambir K Sanghera30, Jouko Saramies184, James Scott143, Laura J Scott14, Robert A Scott92, Ayellet V Segrè44,89,90, Joban Sehmi64,143, Bengt Sennblad97,98, Nabi Shah11, Sonia Shah185, A Samad Shera186, Xiao Ou Shu45, Alan R Shuldiner187,188,189, Gunnar Sigurđsson37,78, Eric Sijbrands190, Angela Silveira97,98, Xueling Sim14,56, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam109, Kerrin S Small13,104, Wing Yee So50, Alena Stančáková139, Kari Stefansson36,134, Gerald Steinbach191, Valgerdur Steinthorsdottir134, Kathleen Stirrups13, Rona J Strawbridge97,98, Heather M Stringham14, Qi Sun61,110, Chen Suo56, Ann-Christine Syvänen192, Ryoichi Takayanagi193, Fumihiko Takeuchi126, Wan Ting Tay18, Tanya M Teslovich14, Barbara Thorand168, Gudmar Thorleifsson134, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir36,134, Emmi Tikkanen80,167, Joseph Trakalo1, Elena Tremoli20,21, Mieke D Trip109, Fuu Jen Tsai54, Tiinamaija Tuomi83,194, Jaakko Tuomilehto133,195,196,197, Andre G Uitterlinden75,76,190, Adan Valladares-Salgado198, Sailaja Vedantam87,88, Fabrizio Veglia20, Benjamin F Voight44,199, Congrong Wang24, Nicholas J Wareham92, Roman Wennauer190, Ananda R Wickremasinghe169, Tom Wilsgaard161, James F Wilson46,47, Steven Wiltshire1,219, Wendy Winckler44, Tien Yin Wong18,19,200, Andrew R Wood95, Jer-Yuarn Wu51,54, Ying Wu144, Ken Yamamoto201, Toshimasa Yamauchi105, Mingyu Yang146, Loic Yengo48,202, Mitsuhiro Yokota203, Robin Young10, Delilah Zabaneh185, Fan Zhang146, Rong Zhang24, Wei Zheng45, Paul Z Zimmet123, David Altshuler44,89,90,204,205,206,221, Donald W Bowden7,8,207,208,221, Yoon Shin Cho209,221, Nancy J Cox34,35,221, Miguel Cruz198,221, Craig L Hanis210,221, Jaspal Kooner64,143,211,221, Jong-Young Lee2,221, Mark Seielstad130,212,213,221, Yik Ying Teo12,56,130,214,215,221, Michael Boehnke14,221, Esteban J Parra137,221, John C Chambers3,64,211,221, E Shyong Tai12,216,217,221, Mark I McCarthy1,5,163,221, and Andrew P Morris1,218,221

Footnotes

Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7BN, UK.

Center for Genome Science, National Institute of Health, Osong Health Technology Administration Complex, Chungcheongbuk-do, Cheongwon-gun, Gangoe-myeon, Yeonje-ri, Korea.

Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Oxford, OX3 7LJ, UK.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA 01702, USA.

Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine Research, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Center for Diabetes Research, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Genomics of Common Disease, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, W12 0NN, London, UK.

Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB1 8RN, UK.

Center for Non-Communicable Diseases Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan.

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK.

Department of Biostatistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2029, USA.

Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Lund University Diabetes Centre, Department of Clinical Science Malmö, Scania University Hospital, Lund University, S-20502 Malmö, Sweden.

Institute of Biomedicine, Physiology, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio Campus, Kuopio, Finland.

Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Ophthalmology, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, via Carlo Parea 4, 20138, Milan, Italy.

Department of Pharmacological Sciences, University of Milan, via Balzaretti 9, 20133 Milan, Italy.

INSERM CESP U1018, F-94807 Villejuif, France.

University Paris Sud 11, UMRS 1018, F-94807, Villejuif, France.

Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai, China.

College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

BioMedical Research Centre, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK.

University of Cambridge Metabolic Research Laboratories, Institute of Metabolic Science, Box 289, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, CB2 OQQ, UK.

NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Metabolic Science, Box 289, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, CB2 OQQ, UK.

Baqai Institute of Diabetology and Endocrinology, Karachi, Pakistan.

Department of Pediatrics, Section of Genetics, College of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA.

Busselton Population Medical Research Institute, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

PathWest Laboratory Medicine of Western Australia, QEII Medical Centre, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

School of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The University of Western Australia, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 60637, USA.

Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 60637, USA.

Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland.

Landspitali University Hospital, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland.

Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University Medical Centre Ulm, Ulm, Germany.

LKC School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore, and Imperial College London, London, UK.

Human Genetics Center, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA 02142, USA.

Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Centre for Population Health Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Teviot Place, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK.

MRC Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, EH4 2XU, UK.

CNRS-UMR-8199, Institute of Biology and Lille 2 University, Pasteur Institute, F-59019 Lille, France.

Clinical Pharmacology and Barts and the London Genome Centre, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Nankang, Taipei, Taiwan.

Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Endocrinology-Diabetology Unit, Corbeil-Essonnes Hospital, F-91100 Corbeil-Essonnes, France.

School of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Centre for Molecular Epidemiology, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Molecular Genetics, Madras Diabetes Research Foundation–Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Advanced Centre for Genomics of Diabetes, Chennai, India.

Department of Preventive Medicine, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea.

Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, National Taiwan University School of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

Department of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, 665 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Collaborative Studies Coordinating Center, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, 21 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119077.

Ealing Hospital National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Middlesex, UK.

Division of Cardiovascular Epidemiology, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Department of Dietetics-Nutrition, Harokopio University, 70 El. Venizelou Str, Athens, Greece.

Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, University of Geneva Medical School, Geneva 1211, Switzerland.

Biomedical Sciences Research Center Al. Fleming, 16672 Vari, Greece.

Inserm UMR 1087, 44007 Nantes, France.

CNRS UMR 6291, 44007 Nantes, France.

Nantes University, 44007 Nantes, France.

Diabetes Research Centre, Biomedical Research Institute, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK.

Pharmacogenomics Centre, Biomedical Research Institute, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK.

Department of Statistics, University of Oxford, 1 South Parks Road Oxford, OX1 3TG, UK.

Department of Epidemiology, Erasmus University Medical Center, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Netherland Genomics Initiative, Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing and Centre for Medical Systems Biology, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Medical Research Council (MRC)-Health Protection Agency (HPA) Centre for Environment and Health, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Icelandic Heart Association, 201 Kopavogur, Iceland.

Clinic of Cardiology, West German Heart Centre, University Hospital of Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, 45122 Essen, Germany.

Department of Chronic Disease Prevention, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki FIN-00271, Finland.

Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland.

Unit of General Practice, Helsinki University General Hospital, Helsinki, Finland.

Folkhälsan Research Center, FIN-00014 Helsinki, Finland.

Unidad de Investigacion en Epidemiologia Clinica, Hospital General Regional I, Dr. Carlos MacGregor, IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico.

Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia.

Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia.

Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Division of Genetics and Endocrinology, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Diabetes Research Center, Diabetes Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

MRC Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Metabolic Science, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK.

Vaasa Health Care Centre, 65100 Vaasa, Finland.

Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Genetics of Complex Traits, Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, Peninsula Medical School, University of Exeter, Magdalen Road, Exeter EX1 2LU, UK.

Department of Epidemiology, Shanghai Cancer Institute, Shanghai, China.

Atherosclerosis Research Unit, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, Sweden.

Institute of Genetic Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany.

Research Unit of Molecular Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany.

Clinical Cooperation Group Diabetes, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Muenchen and Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, Germany.

Clinical Cooperation Group Nutrigenomics and Type 2 Diabetes, Technical University Muenchen and Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, Germany.

German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), 85764 Neuherberg, Germany.

Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology, King’s College London, London, UK.

Department of Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

Diabetes Genetics, Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, Peninsula Medical School, University of Exeter, Barrack Road, Exeter EX2 5DW, UK.

Institute for Clinical Diabetology, German Diabetes Center, Leibniz Center for Diabetes Research at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

HUNT Research Centre, Department of Public Health and General Practice, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Levanger, Norway.

Department of Vascular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, PO-BOX 22660, 1100DD, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

School of Population Health, The University of Western Australia, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College London, 5 University Street, London WC1E 6JJ, UK.

Program in Molecular and Genetic Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, 665 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Department of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, Kinki University School of Medicine, Osaka-sayama, Osaka, Japan.

Hannover Unified Biobank, Hannover Medical School, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Department of Medical Sciences, Molecular Epidemiology and Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University Hospital, SE-751 85 Uppsala, Sweden.

Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

Department of Social Services and Health Care, 68601 Jakobstad, Finland.

Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

Department of Pulmonary Physiology and Sleep Medicine, West Australian Sleep Disorders Research Institute, Queen Elizabeth II Medical Centre, Hospital Avenue, Nedlands WA 6009, Australia.

School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia, Nedlands WA 6009, Australia.

Institute for Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, University Hospital of Essen, Essen, Germany.

Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA.

Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Research Institute, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Diabetes Research Unit, Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Health Sciences, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

Unit of General Practice, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland.

Genome Institute of Singapore, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

School of Systems Biomedical Science, Soongsil University, Dongjak-gu, Seoul, Korea.

Diabetes Prevention Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, 00271 Helsinki, Finland.

deCODE Genetics, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland.

South Ostrobothnia Central Hospital, 60220 Seinäjoki, Finland.

Ministry of Health, Port Louis, Mauritius.

Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto at Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Road North, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada.

Fundacion IMSS, Av. Paseo de la Reforma 476, Mz. Poniente, Col. Juarez, Deleg. Cuauhtemoc, C.P. 06600, Mexico City, Mexico.

Department of Medicine, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio University Hospital, 70210 Kuopio, Finland.

Kuopio Research Institute of Exercise Medicine, Kuopio, Finland.

Centre for Genetic Epidemiology and Biostatistics, The University of Western Australia, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

Office of Population Studies Foundation Inc., University of San Carlos, Cebu City, Philippines.

National Heart and Lung Institute (NHLI), Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK.

Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Beijing Genomics Institute, Shenzhen, China.

Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Akademiska Sjukhuset, SE-751 85 Uppsala, Sweden.

Charles R. Bronfman Institute for Personalized Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

Child Health and Development Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Department of Preventive Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Shanghai Institute of Preventive Medicine, Shanghai, China.

General Medicine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Dr Mohan’s Diabetes Specialties Centre, Chennai, India.

Institute of Human Genetics, University of Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany.

Department of Genomics, Life & Brain Center, University of Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany.

Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, Chair of Genetic Epidemiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 81377 Munich, Germany.

Department of Medicine I, University Hospital Grosshadern, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany.

Respiratory Medicine, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Nedlands, WA 6009, Australia.

Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan.

Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Chubu Rosai Hospital, Nagoya, Japan.

Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Tromsø, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway.

Department of Geriatric Medicine, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan.

Oxford National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre, Churchill Hospital, Old Road Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LJ, UK.

Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55454, USA.

World Class University Program, Department of Molecular Medicine and Biopharmaceutical Sciences, Graduate School of Convergence Science and Technology and College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Box 281, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), Helsinki FIN-00014, Finland.

Institute of Epidemiology II, Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany.

Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Ragama, Sri Lanka

Department of Internal Medicine, Levanger Hospital, Nord-Trøndelag Health Trust, B-7600 Levanger, Norway.

University General Hospital Attikon, 1 Rimini, 12462 Chaidari, Athens, Greece.

Institute of Biometrics and Epidemiology, German Diabetes Center, Leibniz Center for Diabetes Research at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

Department of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland.

Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Partners Center for Personalized Genomic Medicine, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

Department of Metabolic Diseases, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

Health Science and Technology MD Program, Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Harvard Biological and Biomedical Sciences Program, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Boston University Data Coordinating Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Finnish Diabetes Association, Kirjoniementie 15, 33680, Tampere, Finland.

Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland.

Department of Medicine, Central Finland Central Hospital, 40620 Jyväskylä, Finland.

South Karelia Central Hospital, Lappeenranta, Finland.

UCL Genetics Institute, Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

Diabetic Association Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan.

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Program in Personalised and Genomic Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Center, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Department of Clinical Chemistry and Central Laboratory, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany.

Molecular Medicine, Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, SE-751 85 Uppsala, Sweden.

Department of Internal Medicine and Bioregulatory Science, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan.

Department of Medicine, Helsinki University Hospital, University of Helsinki, 000290 HUS Helsinki, Finland.

Instituto de Investigacion Sanitaria del Hospital Universario LaPaz (IdiPAZ), Madrid, Spain.

Centre for Vascular Prevention, Danube-University Krems, 3500 Krems, Austria.

Diabetes Research Group, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Unidad de Investigacion Medica en Bioquimica, Hospital de Especialidades, Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI, IMSS, Av. Cuauhtemoc 330, Col. Doctores, C.P. 06720, Mexico City, Mexico.

University of Pennsylvania - Perelman School of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology, Philadelphia PA 19104, USA.

Centre for Eye Research Australia, University of Melbourne, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Division of Genome Analysis, Research Center for Genetic Information, Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan.

University Lille 1, Laboratory of Mathematics, CNRS-UMR 8524, MODAL team, INRIA Lille Nord-Europe.

Department of Genome Science, Aichi-Gakuin University, School of Dentistry, Nagoya, Japan.

Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Department of Molecular Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Diabetes Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02144, USA.

Department of Biochemistry, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina;

Department of Internal Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Department of Biomedical Science, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Gangwon-do, Korea.

Human Genetics Center, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, P.O. Box 20186, Houston, TX 77225, USA.

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK.

Institute for Human Genetics, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Blood Systems Research Institute, San Francisco, California, USA.

Graduate School for Integrative Science and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Statistics and Applied Probability, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School, Singapore, Singapore.

Department of Biostatistics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 3GA, UK.

Deceased.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

These authors jointly directed this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Writing group. A. Mahajan, M.J.G., W. Zhang, J.E.B., K.J.G., M.H., A.D.J., I.P., E.Z., Y.Y.T., M.B., E.J.P., J.C.C., E.S.T, M.I.M., A.P.M.

Analysis group. A. Mahajan, M.J.G., W. Zhang, J.E.B., K.J.G., T. Ferreira, M.H., A.D.J., M.C.Y.N., I.P., D.S., X.W., E.Z., Y.Y.T., M.B., E.J.P., M.I.M., A.P.M.