Abstract

Background:

The heartwood extract of A. catechu, called pale catechu or “Katha” in Hindi has been widely used in traditional Indian medicinal system. Although various pharmacological properties of this plant had been reported previously, only a few were concerned with the anticancer activity of this plant.

Objective:

The objective was to assess the in vitro anticancer and apoptosis inducing effect of 70% methanolic extract of “Katha” (ACME) on human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MCF-7).

Materials and Methods:

MCF-7 cell line was treated with increasing concentrations of ACME and cell viability was calculated. Flow cytometric methods were used to confirm the apoptosis promoting role of ACME. Morphological changes were then analysed using confocal microscopy. Western blotting was then performed to investigate the expression of apoptogenic proteins and to analyse the activation of caspases.

Results:

ACME showed significant cytotoxicity to MCF-7 cells with an IC50 value of 288.85 ± 25.79 μg/ml. Flow cytometric analysis and morphological studies confirmed that ACME is able to induce apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Furthermore, immunoblot results suggested the pathway of apoptosis induction by increasing Bax/Bcl-2 ratio which results in the activation of caspase-cascade and ultimately leads to the cleavage of Poly adeno ribose polymerase (PARP).

Conclusion:

These results provide the evidence that ACME is able to inhibit the proliferation of MCF-7 cells by inducing apoptosis through intrinsic pathway.

Keywords: Acacia catechu, anticancer, apoptosis, bax/bcl-2, caspase, MCF-7

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a global public health problem because of its high occurrence and mortality rate. Worldwide breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death in women with 4,58,000 deaths annually.[1] Despite developments in diagnosis and advances in therapies using chemotherapy, oncosurgery and radiation, along with various palliative treatments, breast carcinoma remains a great challenge for clinical therapy. Subsequently, new strategies are evolving to control and treat cancer. One such strategy could be the use of herbs and medicinal plants.

Acacia catechu (L.f.) wild (Family-Leguminoseae) is a moderate size deciduous, thorny tree common to Southern Asia and widely distributed in India. It is commonly known as “khair” and its various parts have been used since ancient times in Ayurvedic medicine. The heartwood extract of A. catechu, called pale catechu or “Katha” in Hindi, is a necessary ingredient of “pan” which is beetle leaf preparation chewed in India. In Ayurveda, “Katha” is used in the treatment of cough, dysentery, throat infections, chronic ulcers and wounds.[2] Catechu is also reported for its antimicrobial,[3] anti-inflammatory,[4] immunomodulatory,[5] antipyretic, antidiarrhoeal, hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective[6,7] properties. Gum exudates from this tree also reported to have antioxidant activity.[8] Several natural bioactive compounds such as (+)-catechin, (-)-epicatechin, (-)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate, epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate, quercetin, (+)-cyanidanol have been isolated from heartwood, bark, roots, leaves and stem of A. catechu.[9,10,11] It is also reported that 70% methanolic extract of A. catechu possess antioxidant, iron chelating and DNA protective properties.[12] A. catechu is also proven for its anticancer and cytotoxic potentials against HeLa, COLO-205 and HT-1080 cell lines in vitro.[13]

The present study is aimed to demonstrate the in vitro anticancer activity of 70% methanolic extract of A. catechu heartwood (ACME) on human breast carcinoma MCF-7 through investigation of apoptosis inducing property by studying morphological changes, cell cycle analysis and by checking the expression of anti and pro-apoptotic proteins as well as a caspase cascade pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), antibiotics and amphotercin-B were purchased from HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Fetal bovine serum was purchased from HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Utah, USA. Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1, Annexin-V-FLUOS staining kit and Polyvinyl difluoride membrane were purchased from Roche diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany. RNase A, 4’,6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and Triton X-100 were purchased from MP Biomedicals, France. Non-fat dry milk was purchased from Mother Dairy, G. C. M. M. F. Ltd. AMUL, India. BCIP/NBT substrate was purchased from GeNei™, MERCK, India. Anti- PARP N-terminus, anti-Bcl-2 (NT), anti-Caspase-3 (p17), anti-Caspase-9 and anti-Caspase-8 (IN) antibodies were purchased from AnaSpec, Inc., USA. Anti-Bax and anti-beta-actin antibodies were purchased from OriGene technologies, Inc, Rockville, USA. Alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-Rabbit secondary antibody was purchased from RockLand immunochemicals Inc., Gilbertsville, USA.

Extraction

Pale catechu was purchased from local market and finely powdered. The powder (100 g) was stirred using a magnetic stirrer with 1000 ml 70% methanol in water for 15 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 2850 × g and the supernatant decanted. The process was repeated with the precipitated pellet. The supernatants from two phases were mixed, concentrated in a rotary evaporator and lyophilized. The obtained dried extract was stored at −20°C until use. The working stock solution (20 mg/ml) of ACME was prepared using double distilled water and sterilized using 0.22 μm syringe filter. The obtained sample solution was stored at 4°C until use.

Cell line and culture

Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cell line was purchased from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), India and maintained in sterilized condition. The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 50 μg/ml gentamycin sulphate, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin-B. The cell line was maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

WST-1 assay

Cell viability was quantified using the WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent, Roche diagnostics, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The principle of this assay is based on cleavage of a tetrazolium salt to a formazan by cellular enzymes, especially mitochondrial dehydrogenases.[14] The number of metabolically active cells correlates directly to the amount of formazan. Briefly, 1 × 104 cells/well were treated with ACME ranging from 0-200 μg/ml for 48 hours in 96-well culture plate. After treatment, 10μl of WST-1 cell proliferation reagent was added to each well followed by 3-4 hours of incubation at 37°C. Cell proliferation and viability were quantified by measuring absorbance of the formazan at 460nm using a microplate ELISA reader MULTISKAN EX (Thermo Electron Corporation, USA).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry using the method previously described[15] with slight modifications. 1 × 106 cells were treated with ACME (0-200 μg/ml) for 16h in a 6-well culture plate. After treatment, cells were fixed with suitable amount of chilled methanol and diluted with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). Cells were then treated with RNase A at 37°C for 1h to digest cellular RNA. The nuclear DNA of cells was then stained with propidium iodide (PI) and cell phase distribution was determined on FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson) equipped with 488 nm Argon laser light and 623 nm band pass filter using CellQuest software. A total 10,000 events were acquired and data analysis was done using ModFit software. A histogram of DNA content (x-axis, red fluorescence) vs count (y- axis) was plotted.

Annexin V staining

This assay was performed using Annexin-V-FLUOS Staining kit, Roche diagnostics. The cells (1 × 106) were treated with ACME (0-200 μg/ml) for 16h labelled with PI and Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) according to the protocol of the kit manufacturer. The distribution of apoptotic cells was identified by flow cytometer on FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson) equipped with 488 nm Argon laser light and 623 nm band pass filter using CellQuest software. A total 10,000 events were counted. Cells that were Annexin V (-) and PI (-) were considered as viable cells. Cells that were Annexin V (+) and PI (-) were considered as early stage apoptotic cells. Cells that were Annexin V (+) and PI (+) were considered as late apoptotic or necrotic cells.

DAPI (4’, 6’- diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining

DAPI staining was done using the method described earlier with slight modifications.[16] 5 × 105 cells were treated with ACME (100 μg/ml) for 48h in a 6-well culture plate and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were then stained with 50 μg/ml DAPI for 40 min at room temperature. The cells undergoing apoptosis, represented by the morphological changes of apoptotic nuclei, were observed and imaged from ten eye views at ×63 magnifications under a laser scanning confocal microscope LSM510META (Zeiss).

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with ACME (100 μg/ml) for various time intervals (0.5-24 h). After treatment, cells were lysed with triple detergent cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 150mM NaCl, 0.02% Sodium azide, 0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulphate, 1% triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml phenyl methyl-sulfonyl fluoride, pH 8) and the lysates were then centrifuged at 13800 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were stored at -80°C until use. Protein concentration was measured by Folin-Lowry method. Proteins (50 μg) in the cell lysates were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE for caspase-9, caspase-3 and Bax whereas 40μg of protein used to resolve caspase-8, Bcl-2, PARP and beta-actin on 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to the PVDF membrane using transfer buffer (39 mM Glycine, 48mM Tris base, 20% Methanol, 0.037% Sodium dodecyl sulphate, pH 8.3). The membranes were then blocked with 5% Non-fat dry milk in TBS followed by incubation with corresponding antibodies separately overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS-T, (0.01% of Tween-20 in TBS) membranes were incubated with alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG antibody at room temperature in the dark for 4h, followed by washing. The blots were then developed with BCIP/NBT substrate and the images were taken by the imaging system EC3 Chemi HR (UVP, USA). The blots were then analysed for band densities using ImageJ 1.45s software.

Statistical analysis

Cytotoxicity data was reported as the mean ± SD of 6 measurements and cell cycle analysis data was reported as the mean ± SD of 3 measurements. The statistical analysis was performed by KyPlot version 2.0 beta 15 (32 bit). The IC50 values were calculated by the formula, Y = 100*A1/(X + A1) where A1 = IC50, Y = response (Y = 100% when X = 0), X = inhibitory concentration. The IC50 values were compared by paired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Cell viability assay

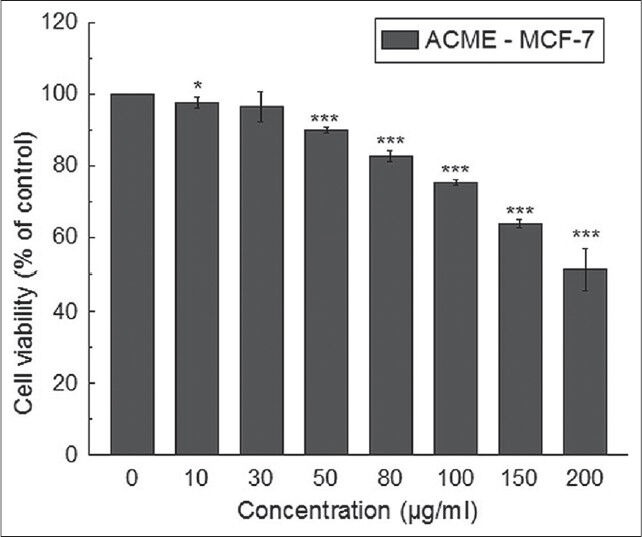

The effect of ACME on cell viability was evaluated by WST-1 assay and the IC50 values were calculated from dose-dependent response studies. Figure 1 showed that ACME was able to exert anti-proliferative effects in the MCF-7 cell line tested in dose-dependent manner. The IC50 value of the ACME for MCF-7 cells was found to be 288.85 ± 25.79 μg/ml after exposure for 48h.

Figure 1.

Effect of ACME on cell proliferation and viability of MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ACME for 48 hours; cell proliferation and viability was determined with WST-1 cell proliferation reagent. Results were expressed as cell viability (% of control). All data is expressed as mean ± SD (n=6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/ml

Flow cytometric cell cycle analysis

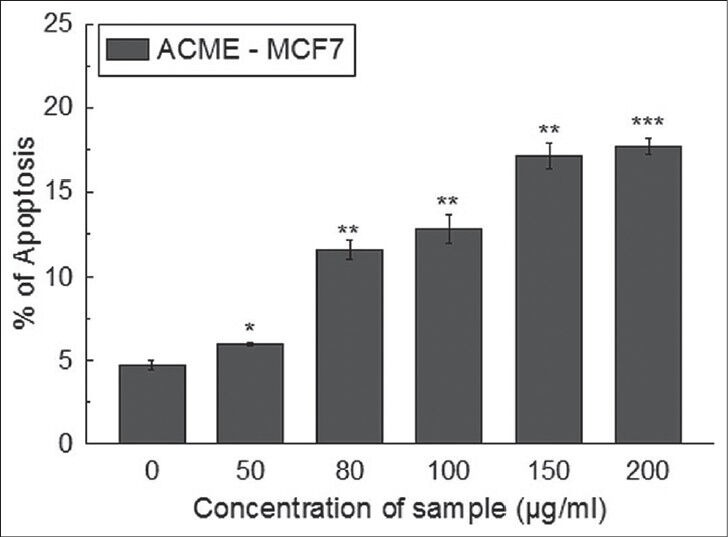

The anti-proliferation effect of ACME on MCF-7 was extended by studying the effect in cell cycle distribution. This study showed that ACME was able to induce significant sub-G1 peak dose dependently 16h post-treatment. The cells in the sub-G1 population were quantified as the apoptotic index [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Cell cycle distribution was determined in propidium iodide stained samples using flow cytometer. Percentage of cells in sub-G1 was calculated for MCF-7 cells after treatment with ACME (0-200 μg/ml) for 16 hours. All data is expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01and ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/ml

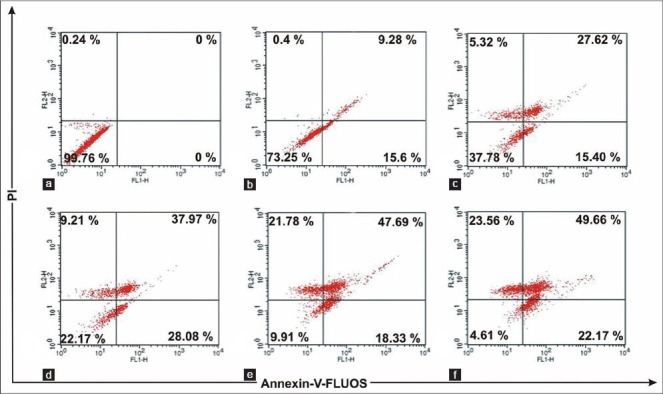

Apoptosis vs. necrosis

From the dot plots [Figure 3], it was observed that with increase in the concentration of ACME the number of early apoptotic and late apoptotic cells were increasing. After 16h treatment with ACME (100 μg/ml), 28% cells were found in early apoptosis and 37% cells were in late apoptosis; while higher concentrations of ACME (150 μg/ml and 200 μg/ml) resulted in the increase of cell population in upper left quadrant which refers to the disrupted cells or the cells undergone necrosis. These results indicated that ACME effectively induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells at 100 μg/ml. So this concentration of ACME was selected for further study to investigate the pathway by which apoptosis had occurred.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric plots of annexin-V-FLUOS and propidium iodide staining of MCF-7 cells treated for 16 hours with different concentrations: Control (a), 50 μg/ml (b), 80 μg/ml (c), 100 μg/ml (d), 150 μg/ml (e), 200 μg/ml (f) of ACME. Numbers in boxes represents % of total cells

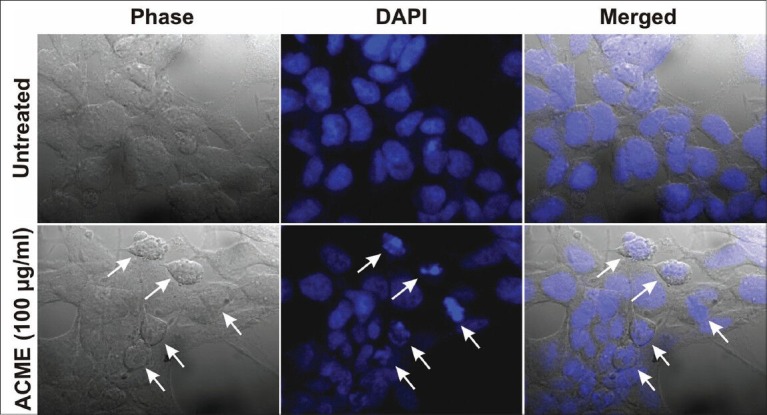

Microscopic observation of ACME-induced apoptotic cells

Both the untreated and ACME (100 μg/ml) treated cells were stained with DAPI and visualised by confocal microscope [Figure 4]. Untreated cells were found with normal morphology and intact nuclei, while the treated cells exhibited the characteristics of apoptosis, with condensed and fragmented nuclei, along with marked shrinkage in the cell membrane.

Figure 4.

Morphological assessment of ACME treated MCF-7 cells for 48 hours. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and observed under confocal microscope. Untreated MCF-7 cells (upper region) and MCF-7 cells treated with 100μg/ml ACME (lower region). White arrows indicate the cells which have undergone apoptosis

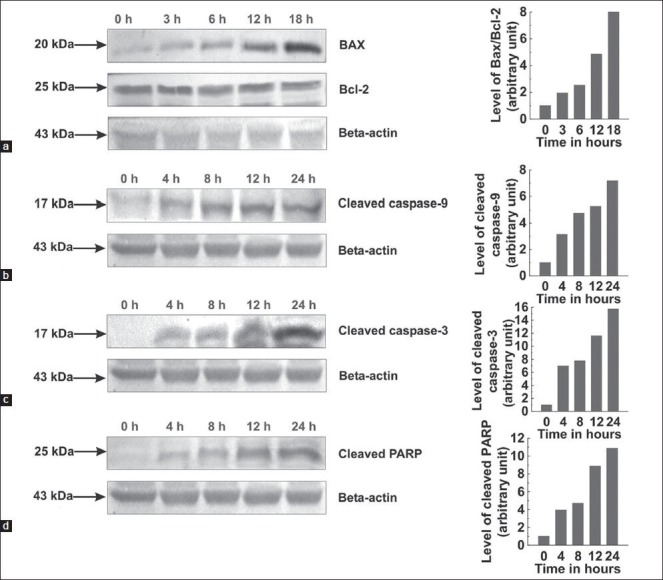

Alteration in expression of apoptogenic proteins

Bcl-2 and Bax protein levels in untreated and treated MCF-7 cells were studied using western blot technique to examine the involvement of Bcl-2 family proteins in ACME mediated apoptosis. As showed in the Figure 5a, ACME dramatically increased the expression of Bax (pro-apoptotic) protein in a time dependent manner while there is no change in the expression of Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic) protein. This resulted in increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio.

Figure 5.

Whole cell lysates were prepared and resolved followed by western blotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. Graphs adjoining the blots represent the levels of the indicated proteins at given time intervals. Effects of ACME on Bax and Bcl-2 expression; MCF-7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml ACME for indicated time intervals (a). Effects of ACME on cleaved caspase-9, cleaved caspase-3 and PARP; MCF-7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml ACME for indicated time intervals (b, c, d)

Effect of ACME on caspases and PARP cleavage

Western blot analysis investigated response of certain caspases to ACME treatment. The 17 kDa subunit of cleaved caspase-9 was found increasing with time in treated cells [Figure 5b]. 17 kDa subunit of cleaved caspase-3 was clearly detected after 4 h of treatment followed by a gradual increase in its level [Figure 5c]. However, the cleavage of caspase-8 to its 28 kDa subunit was not detected in treated cells (Data not shown). Similarly, a role for the cleavage of PARP was shown by the gradual increase in 25 kDa PARP fragment post-treatment with ACME [Figure 5d].

DISCUSSION

Traditional Indian medicine incorporates the use of medicinal plants which are found to serve promising antioxidants and free radical scavenging agents, which ultimately results in prevention of various diseases viz. cancer, autoimmune diseases. The results from our previous study suggested that ACME possesses protective antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities.[12] In addition several researchers have reported that antioxidants, such as retinoids and vitamin E, produce genetic changes that cause apoptosis in cancer cells by mechanisms other than antioxidant effect.[17,18] Our phytochemical study suggests that ACME has abundant amount of carbohydrates, alkaloids, tannins and ascorbate. Furthermore, HPLC standardization of the extract confirms the presence of tannic acid and catechin (unpublished communicated data). In reference with many previously reported pharmacological activities of A. catechu, the present study was carried out to assess its in vitro anticancer activity against breast cancer.

The WST-1 assay showed that ACME is effective in inhibiting the growth of MCF-7 cells dose dependently. The viability of the cells was reduced to 50% upon 48h exposure to ACME. Previously it is reported that the inhibition of growth or reduction in cell viability in presence of anticancer agents resulted from apoptosis, necrosis or cell cycle block.[19] Many cytotoxic agents arrest the cell cycle at G0/G1, S and G2/M phase and then induce apoptosis.[20,21,22,23] The flow cytometric analysis showed that ACME remarkably induced cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 at sub-G1 phase in a dose dependent manner. In addition, apoptosis versus necrosis study demonstrated that ACME induced apoptosis significantly at 100 μg/ml in MCF-7 cells 16h post-treatment. Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation is the primary hallmark to indicate an early event of apoptosis and it represents a point of no return from the path to cell death.[24] The observation from DAPI staining also supported the above dose (100 μg/ml) of ACME to be effective in inducing apoptosis in MCF-7 cells.

Two major mechanisms exist that induce apoptosis by initiating the caspase cascade: The extrinsic involving caspase-8; and the intrinsic pathway involving caspase-9 as the initiator caspase. Expressed as inactive enzymes, caspases are members of a family of cysteine proteases, play a central role in the apoptosis.[25] Once activated, caspase-8 activates the downstream executioner caspase-3 by proteolytic cleavage of their zymogen forms. The other initiator caspase, caspase-9, respond to the release of cytochrome C from the mitochondria. Once released from mitochondria, cytochrome C acts as a co-factor and interacts with Apaf-1 and procaspase-9, which in turn activates caspase-9. This formed apoptosome is then involved in the activation of caspase-3.[26,27,28] Activated caspase 3 is responsible for the proteolytic degradation of PARP, which occurs at the onset of apoptosis.[29] The present study provides the evidence demonstrating that ACME-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells is mediated by increased cleavage of caspase-9, activation of caspase 3, and degradation of PARP and not by the activation of caspase-8. This observation suggested that A. catechu induced the apoptosis in MCF-7 cells by intrinsic pathway.

It has been shown that the Bcl-2 family proteins play an important regulatory role in apoptosis, either as activator (Bax) or as inhibitor (Bcl-2).[30] Of the Bcl-2 family members, the Bax and Bcl-2 protein ratio has been recognized to play a key role in regulation of the apoptotic process.[31,32] The balance between the expression levels of the protein units (Bcl-2 and Bax) is critical for cell survival and death as the increase in Bax/Bcl-2 ratio contributes to the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria and activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathway.[28] Changes in Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and activation of caspase cascade have been reported to be caused by downregulation of Bcl-2 with slight downregulation of Bax,[33] and downregulation of Bcl-2 with upregulation of Bax.[34] In this investigation, it is found that Bax expression was significantly elevated in ACME treated MCF-7 cells while Bcl-2 expression remains unchanged which ultimately results in an increase in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and activation of the caspase cascade.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the present report demonstrates that 70% methanolic extract of Acacia catechu exhibits an anti-proliferative activity by induction of apoptosis through upregulation of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio i.e., through intrinsic pathway. This induction of apoptosis in the breast adenocarcinoma is verified by performing apoptosis assays, microscopic methods and immunoblotting studies. Considering the effect of A. catechu in killing MCF-7 cells, it needs to be tested on several other cell lines, along with further study to characterize the bioactive anticancer compounds present in the same medicinal plant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Ranjan Dutta, Mr. Ranjit K. Das and Mr. Pradip K. Mallick for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.GLOBOCAN 2008 (2012) Cancer Fact sheet. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/on 02.04.2013 .

- 2.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Vol. 2. New Delhi: CSIR Publication; 1996. Glossary of Indian medicinal plants. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel JD, Kumar V, Bhatt SA. Antimicrobial screening and phytochemical analysis of the resin part of Acacia catechu. Pharm Biol. 2009;47:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett BP, Jia Q, Zhao Y, Levy RM. A medicinal extract of Scutellaria baicalensis and Acacia catechu acts as a duel inhibitor of cyclooxygenase and 5-lypoxygenase to reduce inflammation. J Med Food. 2007;10:442–51. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismail S, Asad M. Immunomodulatory activity of Acacia catechu. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;53:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayasekhar P, Mohanan PV, Rathinam K. Hepatoprotective activity of ethyl acetate extract of Acacia catechu. Indian J Pharmacol. 1997;29:426–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray D, Sharatchandra KH, Thokchom IS. Antipyretic, antidiarrhoeal, hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective activities of ethyl acetate extract of Acacia catechu wild. In albino rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38:408–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surveswaran S, Cai Y, Corke H, Sun M. Systemic evaluation of natural phenolic antioxidants from 133 Indian medicinal plants. Food Chem. 2007;102:938–53. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P, Dayal R, Ayyar KS. Chemical constituents of Acacia catechu leaves. J Indian Chem Soc. 1997;74:60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen D, Wu Q, Wang M, Yang Y, Lavoie EJ, Simon JE. Determination of predominant catechins in Acacia catechu by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:3219–24. doi: 10.1021/jf0531499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hye MA, Taher MA, Ali MY, Ali MU, Zaman S. Isolation of (+)-catechin from Acacia catechu (cutch tree) by a convenient method. J Sci Res. 2009;1:300–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazra B, Sarkar R, Biswas S, Mandal N. The antioxidant, iron chelating and DNA protective properties of 70% methanolic extract of ‘Katha’ (Heartwood extract of Acacia catechu) J Complement Integr Med. 2010;7(1) Article 5, doi: 10.2202/1553-38401335. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadumane VK, Nair S. Evaluation of anticancer and cytotoxic potentials of Acacia catechu extracts in vitro. J Nat Pharm. 2011;2:190–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar R, Mandal N. In vitro cytotoxic effect of hydroalcoholic extracts of medicinal plants on Ehrlich's Ascites Carcinoma. Int J Phytomed. 2011;3:370–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machana S, Weerapreeyakul N, Barusrux S, Nonpunya A, Sripanidkulchai B, Thitimetharoch T. Cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of six herbal plants against the human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cell line. BMC Chin Med. 2011;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou C, Liebert M, Grossman HB, Lotan R. Identification of effective retinoids for inhibiting growth and inducing apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. J Urol. 2001;165:986–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turley JM, Fu T, Ruscetti FW, Mikovits JA, Bertolette DC, 3rd, Birchenall-Roberts MC. Vitamin E succinate induces Fas-mediated apoptosis in estrogen receptor-negative human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:881–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan KT, Meng FY, Li Q, Ho CY, Lam TS, To Y, et al. Cucurbitacin B induces apoptosis and S phase cell cycle arrest in BEL-7402 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and is effective via oral administration. Cancer Lett. 2010;294:118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez V, Barber’a O, S’anchez-Parareda J, Marco JA. Phenolic and acetylenic metabolites from Artemisia assoana. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:2619–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres K, Horwitz SB. Mechanisms of taxol-induced cell death are concentration dependent. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3620–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: Cyclins revisited. Cell. 2004;116:221–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orren DK, Petersen LN, Bohr VA. Persistent DNA damage inhibits S-phase and G 2 progression, and results in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1129–42. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen RT, Hunter WJ, 3rd, Agrawal DK. Morphological and biochemical characterization and analysis of apoptosis. J Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:215–28. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(97)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastorino JG, Chen ST, Tafani M, Snyder JW, Farber JL. The overexpression of Bax produces cell death upon induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7770–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: Requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou H, Li Y, Liu X, Wang X. An APAF-1·cytochrome C multimeric complex is a functional apoptosome that activates procaspase-9. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11549–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Gene Dev. 2001;15:2922–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen BD, Rampalli S, Burns LE, Brunette S, Dilworth FJ, Megeney LA. Caspase 3/caspase-activated DNase promote cell differentiation by inducing DNA strand breaks. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4230–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913089107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed JC. Double identity for proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Nature. 1997;387:773–6. doi: 10.1038/42867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson MD, Raff MC. Programmed cell death and Bcl-2 protection in very low oxygen. Nature. 1995;374:814–6. doi: 10.1038/374814a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–19. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian Z, Shen J, Moseman AP, Yang Q, Yang J, Xiao P, et al. Dulxanthone A induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via up-regulation of p53 through mitochondrial pathway in HepG2 cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:31–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang YB, Qin J, Zheng XY, Bai Y, Yang K, Xie LP. Diallyl trisulfide induces Bcl-2 and caspase-3-dependent apoptosis via downregulation of Akt phosphorylation in human T24 bladder cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:363–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]