Abstract

Background:

Resveratrol (RVT), one of the most commonly employed dietary polyphenol, is used in traditional Japanese and Chinese medicine for treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Recently, we have shown that RVT has a potent relaxant effect on rat corpus cavernosum via endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Objective:

The present study addressed the question whether different types of potassium channels are involved in the endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanism of corpus cavernosum relaxation induced by RVT.

Materials and Methods:

Strips of corpus cavernosum from rats were mounted in an organ-bath system for isometric tension studies.

Results:

RVT (1-100 μmol/L) produced concentration-dependent relaxation responses in rat corpus cavernosum pre-contracted by phenylephrine. The non-selective potassium channels blocker tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA, 10 mmol/L), ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels blocker glibenclamide (10 μmol/L), and inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels inhibitor barium chloride (BaCl2, 30 μmol/L) caused a significant inhibition on the relaxation response to RVT, whereas voltage-dependent potassium channels inhibitor 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 1 mmol/L), and large conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels inhibitor iberiotoxin (IbTX, 0.1 μmol/L) did not significantly alter relaxant responses of corpus cavernosum strips to RVT. In addition, relaxant responses to RVT did not significantly inhibited by the combination of selective inhibitors of small and intermediate conductance BKCa channels (0.1 μmol/L charybdotoxin and 1 μmol/L apamin, respectively).

Conclusion:

These results demonstrated that endothelial small and intermediate conductance BKCa channels are not thought to be an important role in RVT-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation of corpus cavernosum. The endothelium-independent corpus cavernosum relaxation induced by RVT is seems to largely depend on Kir channels and KATP channels in corporal tissue.

Keywords: Corpus cavernosum, potassium channels, relaxation, resveratrol

INTRODUCTION

Erectile function depends on a precise balance and interactions between contractile and relaxant factors under normal and pathological conditions that determine the tone of corpora cavernosal smooth muscle of the penis.[1,2] Relaxation of cavernous smooth muscle is critical for inducing and maintaining penile erection. Erectile dysfunction (ED) is commonly defined as the inability to achieve or maintain penile erection sufficient to perform for convincing sexual activity.[3] ED is a widespread problem, which has been estimated to occur in approximately 50% of men between the ages of 40 years and 70 years.[4] This problem affects about 150 million individuals in the World and is viewed by almost all men as a significant component of quality of life.[5] ED is often a disease of vascular origin,[6] which results from impairment of endothelium-dependent or – independent smooth muscle relaxation.[7]

Many traditional Chinese and Japanese medicines can provide a safe natural alternative to reversing ED. Some extracts from traditional Chinese and Japanese herbs, of the alkaloids, phenolic compounds, coumarin and saponin series, relax the smooth muscle of corpus cavernosum, which provides an open window for developing new drugs for the treatment of ED. Resveratrol (RVT), one of the most commonly employed dietary polyphenolic compound which mainly exists in red grapes and wine, was first isolated from the roots of of Polygonum cuspidatum, a plant used in traditional Chinese and Japanese medicine for treatment of cardiovascular diseases. The favorable relaxant effects of RVT have been demonstrated by a substantial number of experimental studies in human internal mammary artery, rat aorta, mesenteric and uterine artery of guinea pig.[8,9,10] Accordingly, in the course of our studies on the development of naturally occurring agents for the treatment of ED, we found that RVT has a potent relaxant effect on rat corpus cavernosum.[11] In this study, relaxant effect produced by RVT has been found to be greatly dependent on endothelium-independent mechanisms. However, the mechanisms underlying endothelium-independent relaxation of corpus cavernosum induced by RVT is unknown.

It has been shown that potassium channels play an important role for the modulation of corpus cavernosum smooth muscle cell tone. Activation of potassium channels followed by hyperpolarization and relaxation of corporal smooth muscle cells is thought to be an important mechanism in penile erection.[12,13,14,15] Because corporeal endothelium and smooth muscle contains several potassium channels, it is expected that drugs interfering with these channels may affect relaxation in corporal tissue. Thus, the present study has addressed the question of whether different types of potassium channels are involved in both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms of vasodilatation induced by RVT in rat corpus cavernosum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental procedures

This study was registered by the Animal Ethics Committee of Akdeniz University Medical Faculty, Antalya, Turkey. Briefly, male Wistar rats, weighing 250-300 g, were used in the present study. All animals were housed under the standard animal laboratory conditions (12 h lighting cycle, controlled temperature and humidity).

Isolated organ bath technique

The rats were humanly killed by cervical dislocation. Penises were surgically removed at the level of the crural attachments to the pubo-ischial bones and promptly placed in a Petri dish containing Krebs solution (containing in mM: NaCl 118, KCl 5, NaHCO3 25, KH2PO4 1.0, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, and glucose 11.2), bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The glans penis and urethra were excised and the corpus cavernosum tissue was then dissected free from the tunica albuginea. The two corpus cavernosums were separate by cutting the fibrous septum between them. The time frame from dissection of corpus cavernosum to organ bath experiments was about 20 min. Each cavernosal strip was tied with silk in one organ chamber with one end fixed to a tissue holder and the other secured to a force transducer. Cavernosal strips were maintained in the organ baths with filled with Krebs solution maintained at 37 °C and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to obtain a pH of 7.4. Isometric tension was continuously measured using an isometric force transducer (FDT05, Commat Ltd., Ankara, Turkey), connected to a computer-based data acquisition system (MP36, Commat Ltd., Ankara, Turkey). 500 mg of tension was applied to each strip and allowed to equilibrate for 60 min. During the resting periods, the organ bath solution was changed every 15 min. For the relaxation studies, corpus cavernosum strips were precontracted with phenylephrine (Phe, 10 μmol/L). This concentration was determined from the cumulative contraction – response curves to achieve 80% of the maximum contraction.

Protocol

After further rinsing, endothelium-intact corpus cavernosum tissues precontracted with Phe were exposed to RVT in the presence of the combination of selective inhibitors of small (SKCa) and intermediate (IKCa) conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels (0.1 μmol/L charybdotoxin and 1 μmol/L apamin, respectively), and relaxation responses were recorded. To investigate the role of different potassium channels on endothelium-independent corpus cavernosum relaxation induced by RVT, tissues were incubated with non-selective potassium channels blocker, tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA, 10 mmol/L); ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels blocker, glibenclamide (10 μmol/L); inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels inhibitor, barium chloride (BaCl2, 30 μmol/L); voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels inhibitor, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 1 mmol/L), and large conductance BKCa channels inhibitor, iberiotoxin (IbTX, 0.1 μmol/L) and relaxation responses were obtained. TEA, glibenclamide, BaCl2, 4-AP, apamin, charybdotoxin and IbTX were added to the bath 30 min before the study.

Materials

Acetylcholine, phenylephrine, TEA, glibenclamide, BaCl2, 4-AP, apamin, charybdotoxin, IbTX and the salts for the Krebs solution were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). All drugs were prepared fresh daily during experiments and were dissolved in distilled water before use, except in the case of glibenclamide and RVT (initially dissolved in ethanol).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM responses to RVT are expressed as percentages of the reversal of the tension developed in response to Phe. The logarithm of the concentration of agonists which elicited a 50% of maximal response (Emax) was designated as the EC50. These values were determined by regression analysis of the linear portions of the log concentration–response curves. Sensitivity was expressed as pD2 (-log EC50). Statistical analysis of the results was performed by the Student's t-test. P value lower than 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Investigating the role of the KATP channels, Kir channels, Kv channels, and large conductance BKCa channels in RVT-induced endothelium-independent corpus cavernosum relaxation

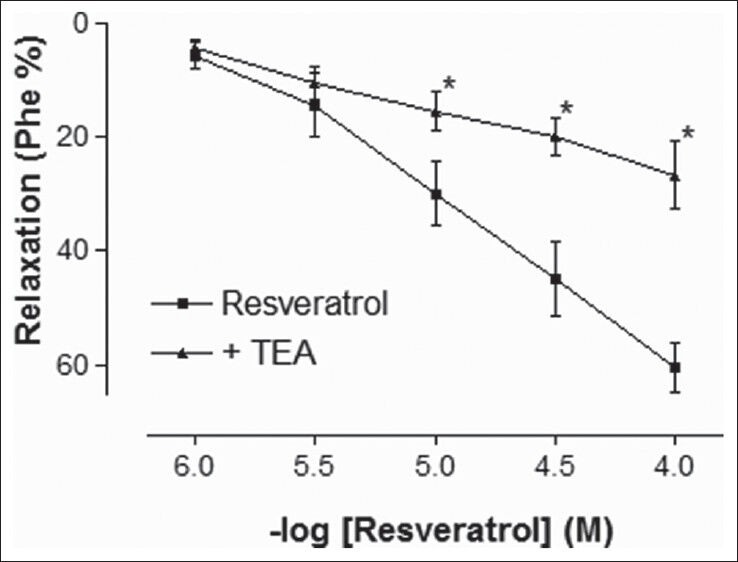

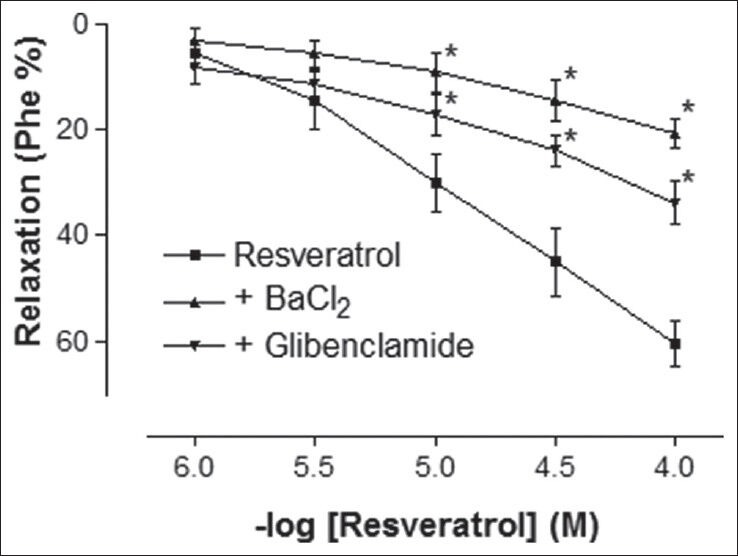

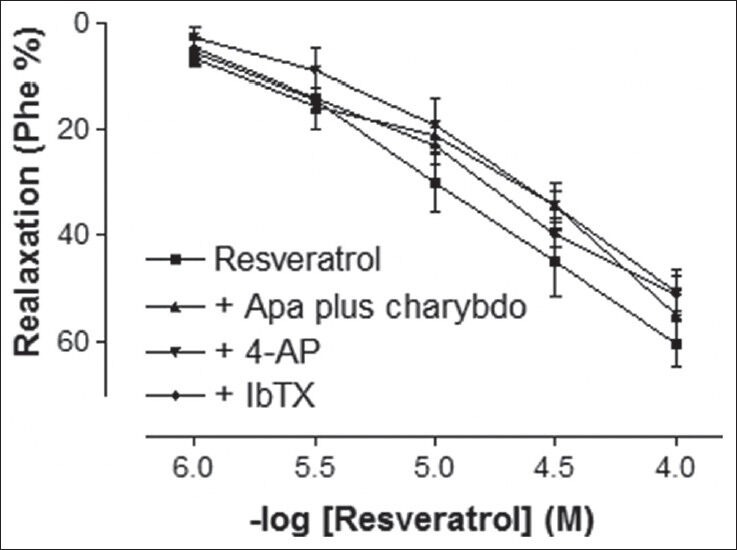

Phe elicited a stable contraction in rat corpus cavernosum strips. In the endothelium-intact tissues, which were precontracted with Phe, addition of RVT (1-100 μmol/L) caused a potent relaxation response in a concentration-dependent manner [Figure 1]. The maximal relaxation response to 100 μmol/L RVT was 60.60 ± 4.32%. The final concentration of solvent in the organ bath was less than 0.1%, which had no effect on basal tone of the corpus cavernosum strips. Preincubation of corpus cavernosum strips with non-specific potassium channel blocker TEA caused a significant reduction of the relaxation response to RVT [Figure 1] (P < 0.05). In addition, the relaxant response induced by RVT was significantly inhibited by both ATP-sensitive potassium channels blocker, glibenclamide and inward rectifier potassium channels inhibitor, BaCl2 [Figure 2] (P < 0.05). However, the relaxant effect induced by RVT was not significantly inhibited by Kv channels inhibitor, 4-AP or large conductance BKCa channels inhibitor, IbTX [Figure 3] (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) (10 mmol/L) incubation on resveratrol (RVT)-induced relaxation responses in rat corpus cavernosum. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM n = 5-7 for all groups. TEA: Tetraethylammonium chloride, *P < 0.05 as compared with RVT

Figure 2.

Effect of BaCl2 (30 μmol/L) and glibenclamide (10 μmol/L) incubation on resverastrol-induced relaxation responses in rat corpus cavernosum. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM n = 5-7 for all groups. BaCl2: Barium chloride, *P < 0.05 as compared with resveratrol

Figure 3.

Effect of apamin (0.1 μmol/L) plus charybdotoxin (1 μmol/L), 4-AP (1 mmol/L), and iberiotoxin (IbTX) (0.1 μmol/L) incubation on resveratrol-induced relaxation responses in rat corpus cavernosum. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM n = 5-7 for all groups. Apa plus charybdo: Apamin plus charybdotoxin, 4-AP: 4-aminopyridine, IbTX: Iberiotoxin

Investigating the role of the small (SKCa) and intermediate (IKCa) conductance BKCa channels in RVT-induced endothelium-dependent corpus cavernosum relaxation

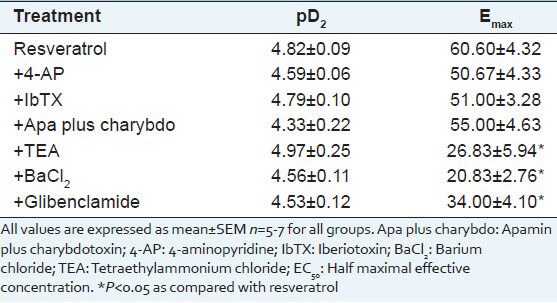

The incubation of endothelium-intact corpus cavernosum strips with the combination of selective inhibitors of small and intermediate conductance BKCa channels (apamin and charybdotoxin, respectively) did not significantly reduce RVT-induced relaxation [Figure 3]. After the incubation with apamin plus charybdotoxin, RVT (100 μmol/L)-induced maximal relaxation decreased from 60.60 ± 4.32% to 55.00 ± 4.63%. In addition, none of the potassium channel blockers did cause a significant change in sensitivity (pD2) to RVT. Emax and pD2 values for RVT are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

pD2 (–log EC50) and Emax values for resveratrol in rat corpus cavernosa strips

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates that different types of potassium channels are involved in the relaxant effect of RVT in corpus cavernosum. This effect is concentration-dependent and mediated through both Kir channels and KATP channels.

The previous results suggest a functional role for potassium channels in the relaxation of corporal smooth muscle relaxation.[16,17] Activation of potassium channels both in the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle causes hyperpolarization which leads to vascular smooth muscle relaxation.[18,19] Hyperpolarization leads to the closure of voltage-dependent calcium channels, leading to a reduction in calcium ion influx, and results in vasodilation.[20] Potassium ion channels are important to stabilize the membrane potential and reduce the excitability of nerves and muscle cells including penile smooth muscle cells.[21,22] Although RVT has been shown to have a potent relaxant effect on rat corpus cavernosum, the role of potassium channels in this effect is unknown. Several potassium channels may be possible to explain the relaxant effect of RVT in rat corpus cavernosum strips. Accordingly, we have recently provided evidence that relaxant response to RVT in corpus cavernosum may be mediated by potassium channels. Among them, endothelial potassium channels have been widely implicated in endothelial hyperpolarization which spreads through myendothelial junctions to result in adjacent smooth muscle hyperpolarization and relaxation of the smooth muscle.[23] It has been suggested that potassium efflux from endothelial cells via IKCa and SKCa activates Kir channels on the smooth muscle cells.[24] In the present study, blockade of small and intermediate conductance BKCa channels, which are found mainly on the endothelium did not cause a significant inhibitor effect on the relaxing effect of RVT in rat corpus cavernosum. In the present study, the relaxant effect of RVT in endothelium-intact corpus cavernosum strips was not significantly abolished by the combination of selective inhibitors of SKCa and IKCa channels (charybdotoxin and apamin, respectively), suggesting that this effect is not mediated by small and intermediate conductance BKCa channels located in the endothelium of corpus cavernosum.

Otherwise, in a recent previous study,[11] we have also demonstrated that the relaxation response of corpus cavernosum induced by RVT was not completely inhibited by the removal of endothelium, supporting the role of endothelium-independent mechanisms in RVT-induced relaxation. The relaxant effects that are resistant to endothelial removal could be attributed to hyperpolarization of the cell membrane by opening different potassium channels in corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. Because potassium channels are the dominant ion conductive pathway in vascular smooth muscle, activation of different types of potassium channels leads to membrane hyperpolarization and inhibition of calcium influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels, resulting in smooth muscle relaxation.[25] Potassium channels exist invascular smooth muscle as four types - Kir channels, Kv channels, BKCa channels and KATP channels.[26] Depending on the vascular bed and species, different potassium channels have been implicated in relaxation response induced by RVT. For example, the mechanism of vasorelaxation of rat mesenteric artery induced by RVT probably involves activation of 4-AP-sensitive potassium channels.[27] Otherwise, the activation of BKCa channels in smooth muscle contributes to the endothelium-independent dilation caused by RVT in isolated porcine retinal arterioles.[28] Besides, Novakovic et al.[29,30] reported that 4-aminopiridine and margatoxin-sensitive potassium channels located in the smooth muscle are involved in the relaxating effect of RVT in both rat aorta and human internal mammarian artery. As reported above, types of potassium channels involved in RVT-induced relaxation may be different in various types of tissues. Among the several subtypes of potassium channels, KCa channels and Kir channels involving KATP channel subtypes are thought to be the most physiologically relevant in corporal smooth muscle.[31,32] In addition, several studies have been published on the presence of KATP channels, and Kir channels, in corpus cavernosa.[17,33] Hence, in our study, different specific potassium channel blockers were tested to identify which one(s) play a role in RVT-induced relaxation of corpus cavernosum. Results of this study showed that the relaxation response of corpus cavernosum to RVT was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with nonspecific potassium channel blocker TEA, suggesting that it may be associated with hyperpolarization due to activation of potassium channels. Previous studies have suggested that RVT acts by way of KV and BKCa channel opening action in various arteries. Therefore, it could be suggested that RVT preferentially stimulates the KV and BKCa channels in the corpus cavernosum. Surprisingly, in the present experiment, we found the treatment of corpus cavernosum tissues with 4-AP (Kv channel blocker) and IbTX (BKCa channel blocker) did not change the relaxant activity of RVT. These findings suggest that the relaxant effect of RVT is unrelated to BKCa channels and Kv channels. The present study also demonstrated the KATP channel blocker, glibenclamide, was able to reduce the relaxation induced by RVT, suggesting the role of KATP channels in RVT-induced corpus cavernosum relaxation. Besides, Kir channels are expressed in arterial smooth muscle, where they are responsible for membrane hyperpolarization and blood vessel dilation.[34,35] Smooth muscle Kir channels are likely to be the target since most blood vessels dilate to potassium in the absence of the endothelium.[36,37,38] The relaxation response of corpus cavernosum to RVT was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with Kir channel blocker BaCl2, suggesting that Kir channels located in smooth muscle may contribute toward the relaxation of corpus cavernosum induced by RVT.

In conclusion, relaxation effect of RVT on corporal smooth muscle was not due to the activation of endothelial potassium channels (SKCa and IKCa). The present data show that RVT induced the relaxation of corporal smooth muscle through greatly endothelium-independent mechanisms. The efficacy of RVT is closely associated with potassium channels in smooth muscle cells, especailly at high concentrations (more than 10 μmol/L). This acute vasorelaxant effect of RVT seems to be mediated by Kir channels and KATP channels, but not by BKCa or KV channels in the smooth muscle of corpus cavernosum. As molecules participating in local regulation of penile smooth muscle contractility can be considered targets for the development of new drugs to treat ED, RVT might be a therapeutically viable strategy in managing this condition via activation of various types of potassium channels.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by Akdeniz University Research Foundation with the 2012.01.0103.004 project number

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burnett AL, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, Chang TS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: A physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257:401–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajfer J, Aronson WJ, Bush PA, Dorey FJ, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide as a mediator of relaxation of the corpus cavernosum in response to nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurotransmission. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:90–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201093260203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lue TF, Giuliano F, Montorsi F, Rosen RC, Andersson KE, Althof S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in men. J Sex Med. 2004;1:6–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: Results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, McKinlay JB. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40 to 69 years old: Longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Urol. 2000;163:460–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayta IA, McKinlay JB, Krane RJ. The likely worldwide increase in erectile dysfunction between 1995 and 2025 and some possible policy consequences. BJU Int. 1999;84:50–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlachopoulos C, Rokkas K, Ioakeimidis N, Stefanadis C. Inflammation, metabolic syndrome, erectile dysfunction, and coronary artery disease: Common links. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naderali EK, Smith SL, Doyle PJ, Williams G. The mechanism of resveratrol-induced vasorelaxation differs in the mesenteric resistance arteries of lean and obese rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;100:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CK, Pace-Asciak CR. Vasorelaxing activity of resveratrol and quercetin in isolated rat aorta. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:363–6. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naderali EK, Doyle PJ, Williams G. Resveratrol induces vasorelaxation of mesenteric and uterine arteries from female guinea-pigs. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;98:537–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalaklioglu S, Ozbey G. The potent relaxant effect of resveratrol in rat corpus cavernosum and its underlying mechanisms. Int J Impot Res. 2013;25:188–93. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2013.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Archer SL. Potassium channels and erectile dysfunction. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;38:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christ GJ. K+channels and gap junctions in the modulation of corporal smooth muscle tone. Drug News Perspect. 2000;13:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christ GJ. K channels as molecular targets for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. J Androl. 2002;23:S10–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SW. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in corporal smooth muscle. Drugs Today (Barc) 2000;36:147–54. doi: 10.1358/dot.2000.36.2-3.568788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz Rubio JL, Hernández M, Rivera de los Arcos L, Benedito S, Recio P, García P, et al. Role of ATP-sensitive K+channels in relaxation of penile resistance arteries. Urology. 2004;63:800–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Insuk SO, Chae MR, Choi JW, Yang DK, Sim JH, Lee SW. Molecular basis and characteristics of KATP channel in human corporal smooth muscle cells. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:258–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:69–78. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams DJ, Barakeh J, Laskey R, Van Breemen C. Ion channels and regulation of intracellular calcium in vascular endothelial cells. FASEB J. 1989;3:2389–400. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.12.2477294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson KE, Wagner G. Physiology of penile erection. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:191–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:921–31. doi: 10.1038/nrn1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman HA, Tare M, Parkington HC. Endothelial potassium channels, endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and the regulation of vascular tone in health and disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:641–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, Weston AH. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature. 1998;396:269–72. doi: 10.1038/24388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han DH, Lee JH, Kim H, Ko MK, Chae MR, Kim HK, et al. Effects of Schisandra chinensis extract on the contractility of corpus cavernosal smooth muscle (CSM) and Ca2+homeostasis in CSM cells. BJU Int. 2012;109:1404–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng CF, Koon CM, Cheung DW, Lam MY, Leung PC, Lau CB, et al. The anti-hypertensive effect of Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) and Gegen (Pueraria lobata) formula in rats and its underlying mechanisms of vasorelaxation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gojkovic-Bukarica L, Novakovic A, Kanjuh V, Bumbasirevic M, Lesic A, Heinle H. A role of ion channels in the endothelium-independent relaxation of rat mesenteric artery induced by resveratrol. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:124–30. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08128fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagaoka T, Hein TW, Yoshida A, Kuo L. Resveratrol, a component of red wine, elicits dilation of isolated porcine retinal arterioles: Role of nitric oxide and potassium channels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4232–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novakovic A, Bukarica LG, Kanjuh V, Heinle H. Potassium channels-mediated vasorelaxation of rat aorta induced by resveratrol. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;99:360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novakovic A, Gojkovic-Bukarica L, Peric M, Nezic D, Djukanovic B, Markovic-Lipkovski J, et al. The mechanism of endothelium-independent relaxation induced by the wine polyphenol resveratrol in human internal mammary artery. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;101:85–90. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0050863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan SF, Brink PR, Melman A, Christ GJ. An analysis of the Maxi-K+ (KCa) channel in cultured human corporal smooth muscle cells. J Urol. 1995;153:818–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christ GJ, Spray DC, Brink PR. Characterization of K currents in cultured human corporal smooth muscle cells. J Androl. 1993;14:319–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva LF, Nascimento NR, Fonteles MC, de Nucci G, Moraes ME, Vasconcelos PR, et al. Phentolamine relaxes human corpus cavernosum by a nonadrenergic mechanism activating ATP-sensitive K+channel. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:27–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley KK, Jaggar JH, Bonev AD, Heppner TJ, Flynn ER, Nelson MT, et al. Kir2.1 encodes the inward rectifier potassium channel in rat arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 1999;515:639–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.639ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaritsky JJ, Eckman DM, Wellman GC, Nelson MT, Schwarz TL. Targeted disruption of Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 genes reveals the essential role of the inwardly rectifying K(+) current in K(+)-mediated vasodilation. Circ Res. 2000;87:160–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savage D, Perkins J, Hong Lim C, Bund SJ. Functional evidence that K+ is the non-nitric oxide, non-prostanoid endothelium-derived relaxing factor in rat femoral arteries. Vascul Pharmacol. 2003;40:23–8. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knot HJ, Zimmermann PA, Nelson MT. Extracellular K(+)-induced hyperpolarizations and dilatations of rat coronary and cerebral arteries involve inward rectifier K(+) channels. J Physiol. 1996;492:419–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson TD, Marrelli SP, Steenberg ML, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr Inward rectifier potassium channels in the rat middle cerebral artery. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R541–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]