Abstract

Acne vulgaris is the most common condition treated by physicians worldwide. Though most acne patients remit spontaneously, for the ones that do not or are unresponsive to conventional therapy or have obvious cutaneous signs of hyperandrogenism, hormonal therapy is the next option in the therapeutic ladder. It is not strictly indicated for only those patients who have cutaneous or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, but can be used even without any evidence of hyperandrogenism, for therapy-resistant acne. It can be prescribed as monotherapy, but when used in combination with other conventional therapies, it may prove to be more beneficial. Hormonal evaluation is a prerequisite for hormonal therapy, to identify the cause behind hyperandrogenism, which may be ovarian or adrenal. This article reviews guidelines for patient selection and the various available hormonal therapeutic options, their side-effect profile, indications and contraindications, and various other practical aspects, to encourage dermatologists to become comfortable prescribing them.

Keywords: Acne, hyperandrogenism, hormonal therapy

Introduction

What was known?

Hormonal imbalance has long been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of persistent and conventional therapy-resistant acne. For adult women with obvious cutaneous or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism who suffer persistant and treatment-resistant acne eruption, hormonal therapy has proved to be beneficial.

Acne vulgaris is the most common skin condition treated by physicians worldwide, affecting about 80% of adolescents and young adults aged 11-30 years. Ninety percent of the patients spontaneously remit before 30 years of age, leaving the rest with an unpredictable course or persistence well into the 5th and 6th decades.[1,2] The main contributing pathogenic pathways of acne are follicular epidermal hyperproliferation and plugging, excess sebum production, activity of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.[3,4] Numerous topical and systemic drugs have been developed for the management of acne over the past 25 years and the voluminous amount of clinical trial information has become increasingly difficult for individual physician to monitor constantly. In 2003, a group of physicians and researchers in the field of acne, known as the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne, published recommendations for the management of acne. They formulated treatment guidelines according to the severity of acne with therapeutic agents like comedolytic agents, antimicrobial agents, and agents that suppress sebum production.[5,6]

Various studies have shown that a significant percentage of adult women with acne failed to respond to treatment with systemic antibiotics and isotretinoin,[4,7,8] which indicates a need for treatment alternatives with improved effectiveness and acceptable side effects for resistant acne. Hormonal therapy opens up new vistas for therapeutic advancement because in acne pathogenesis, hormones appear to play a significant role in enhancing sebum production. Hormonal therapies are not strictly indicated for only those patients who have cutaneous or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, but can be used even for therapy-resistant acne, without hyperandrogenemia.[5] A good understanding of androgen milieu in human body would allow us to better target therapy.

What are the hormones implicated to have a role in acne pathogenesis?

Androgens

Increased sebum production due to androgens’ activity at the sebaceous follicle is a prerequisite for acne in all patients. High level of androgens, or hypersensitivity of the sebaceous glands to a normal level of androgens, causes an increase in sebum production.[9,10,11] In addition, androgens may also enhance follicular hyperkeratosis independent of their effect on the sebaceous glands.[12] Androgen receptors and enzymes involved in androgen biosynthesis are also present in the portion of follicle where plugging first begins and that is how androgen may be involved in initiating the development of the earliest lesion of acne and microcomedones.[13] On the basis of these findings, anti-androgenic hormonal therapy has been examined as a possible treatment of acne in women.

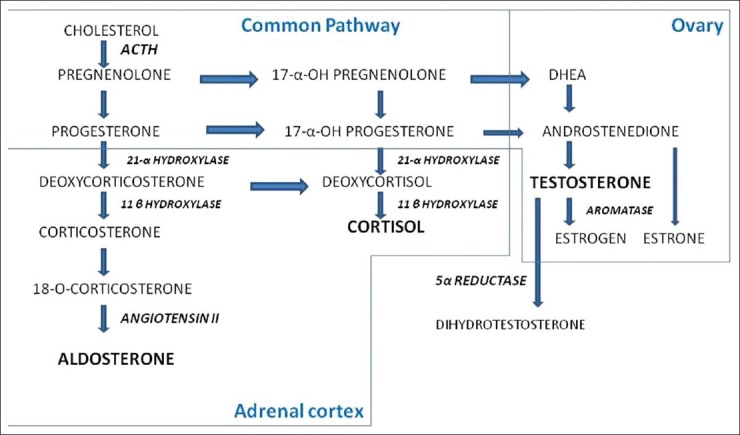

Androgens are C-19 steroids (containing 19 carbons) derived from adrenal cortex and ovaries in females.[14] Zona reticularis in adrenal cortex and theca lutein cells in mature follicle in ovaries are the predominant sites where androgen production takes place and it follows the same synthetic pathways in both the places. Androgenic hormones include strong androgen, which is testosterone, and weaker androgens like androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Weak androgens like androstenedione and DHEA get converted to testosterone in peripheral tissues like adipose tissue, muscle, and skin. Finally, testosterone gets converted to dihydrotestosterone by 5α reductase before it binds androgen receptors in target tissues[15,16,17] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Steroidogenesis in adrenal cortex and ovaries. Adapted from Williams Text book of Endocrinology; 11th edition

Progesterone

Progesterone is a competitive inhibitor of 5α reductase and might be expected to reduce gland activity. The fluctuation of sebum production in women during menstrual cycle and premenstrual flare has partly been blamed on progesterone, which is yet to be proved experimentally though.[18,19]

Estrogen

Estrogen, in high doses, decreases the size of sebaceous gland and reduces sebum production by reducing endogenous androgen production via a negative feedback effect on the pituitary gonadal axis.[20]

Insulin

High levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) increase the production of sebum. They promote androgen synthesis in ovaries by helping theca cells to escape desensitization to high level of luteinizing hormone (LH). IGFs and IGF-binding protein 3 have been implicated in acnegenesis.[21]

Adrenocortical hormones

Glucocorticoids stimulate sebocyte proliferation. Hydrocortisone given to prepubertal boys causes enlargement of sebaceous glands.[22]

Pituitary hormones

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): Stimulates adrenal androgen production to some extent and plays its part in sebum production stimulation.[22]

Growth hormone (GH): GH stimulates sebocyte differentiation and potentiates 5α reductase, and also acts on peripheral tissues to stimulate production of IGFs 1 and 2.[21]

LH: Theca lutein cells of ovarian follicle secrete androgens under the influence of LH in an incremental manner up to the point of desensitization.[21]

Prolactin: Acnegenesis can be stimulated by hyperprolactinemia.[23]

Out of all the hormones that can affect acnegenesis, androgens are the most important. Therefore, a detailed understanding of androgen synthesis and the pathology behind hyperandrogenism is a must for dermatologists to formulate a tailored therapy for individual patient's need.

When to suspect underlying hormonal pathology for acne? Or do all patients of acne need hormonal evaluation? What is the most likely pathology behind hyperandrogenism?

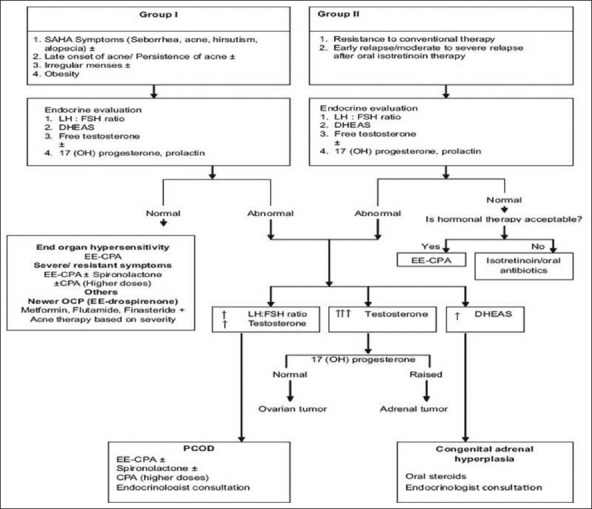

All acne sufferers do not need complete hormonal evaluation because most acne patients either have a self-limiting course or respond to conventional treatment [Figures 2 and 4].[1,2] A hormonal evaluation is reserved for those patients who experience the following:

Figure 2.

Conventional therapy-resistant acne in a 32-year-old lady with PCOS

Figure 4.

Acne with hirsutism in a 21-year-old girl

Therapy-resistant acne, especially those who fail to respond to isotretinoin therapy or relapse shortly after discontinuing isotretinoin or oral contraceptives (OCs) [Figure 2][24]

Those who develop late-onset (adult acne, after 35 years of age),[5] or sudden-onset, or severe, unresponsive, and persistent acne [Figure 3]

Prepubertal acne[25]

Stress exacerbated acne[26]

Associated signs of hyperandrogenism, such as hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, seborrhea, or SAHA syndrome (seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, and androgenetic alopecia) [Figure 4][5]

Patients with associated signs of virilization like male body contour, deepening of voice, cliteromegaly, hirsutism, etc[27]

Females with history suggestive of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) like menstrual irregularities, infertility, weight gain, and insulin resistance.[5]

HAIR-AN syndrome (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans)[5]

Associated with cutaneous signs of hyperinsulinemia, such as acanthosis nigricans, skin tags, mid-truncal obesity, etc.

Figure 3.

Acne with a jaw line distribution in a 40-year-old lady with hirsutism

Clinically, patients with hormone-related acne can be recognized by the concentration of lesions along the jaw line and chin.[13] It has been seen that more than 50% of adult female patients of persistent acne have at least one abnormal hormonal level.[28,29,30] One can follow the Indian Acne Alliance (IAA) consensus guidelines for selecting patients for hormonal therapy[31] [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

IAA consensus guidelines for acne patient selection for hormonal therapy

There are various causes of hyperandrogenism in females. Ovarian causes of hyperandrogenism are PCOS or benign or malignant ovarian tumors. Adrenal causes of hyperandrogenism are classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), non-classical adrenal hyperplasia (NCAH), and benign or malignant adrenal tumors.[15,16] PCOS accounts for 95% of hyperandrogenemia in women, and it is a conglomerate of endocrine abnormalities arising from generalized dysregulation of steroidogenesis, with or without ovarian cyst formation. The predominant pathology in PCOS is chronic anovulation because of continuous high level of estrogen. Rotterdam criteria for PCOS need the presence of at least two out of three findings, and they are oligo-ovulation or anovulation manifesting as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, clinical or biochemical evidence of androgen excess, and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound[32] (12 or more follicles in one ovary, measuring 2-9 mm in diameter, or total ovarian volume greater than 10 mm3).[33] Hyperinsulinemia is an important extrinsic factor in many cases of PCOS and raised insulin level helps theca leutin cells to escape desensitization to increasing level of LH which potentiates androgen synthesis.[34,35] About half of the cases of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism are accompanied by a related type of functional adrenal hyperandrogenism as well.[36]

How often do you find abnormal hormonal levels in hormone-responsive acne patients?

Many patients with hormone-responsive acne will not have measurable increases in circulating total testosterone. This is, in part, because only 1-2% of total testosterone circulates free in blood and the rest of it is bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and unavailable for androgen receptor binding. So, unless free testosterone is measured separately, total testosterone level may still be normal in spite of obvious hyperandrogenism signs.[36,34] Cutaneous signs of hyperandrogenism with a normal androgen level in blood can be either due to increased responsiveness of the pilosebaceous unit to the normal androgen level or increased activity of 5α reductase, which converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, which is 5 times more potent than testosterone.

What are the investigations to be ordered when hormonal cause is suspected in a female patient?

For patients with cutaneous hyperandrogenism, hormonal evaluation is a prerequisite for hormonal therapy. The patient should be off any OCs or any other hormonal therapy for at least 1 month before testing and the tests should be performed at the onset of menses (luteal phase).[27] The hormones that need to be investigated for are:

Testosterone (free and total): If there is only a modest elevation of total testosterone, but remains < 200 ng/dl, it is probably due to a benign pathology such as PCOS or adrenal hyperplasia. Beyond this level, one should suspect androgen-secreting neoplasia of either ovaries or adrenals.[37]

Androstenedione: Androstenedione secretion follows a circadian rhythm and has its peak in the morning; hence, early morning sample between 0700 and 0900 h should be measured. Androstenedione is normally secreted equally from both ovaries and adrenals.[14]

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): 90% of DHEA and 98% of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) are secreted from zona reticularis of adrenal cortex. Hence, elevated level of DHEA and its sulfate points toward an adrenal source. Modest elevation of DHEAS (4000-8000 ng/dl) may indicate benign adrenal hyperplasia, while higher levels should prompt evaluation for an adrenal tumor.[14,37]

SHBG: If SHBG level in blood decreases, then free testosterone level in blood goes up resulting in a state of relative hyperandrogenism.[14]

17-OH-progesterone: Is expected to be elevated (>200 ng/dl) in CAH or NCAH because when there is deficiency or absence of 21α hydroxylase, the pathways dedicated for aldosterone and cortisol synthesis get blocked and androgen secretion pathway gets accelerated.[37]

LH: Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio: A ratio of > 3 is seen in PCOS patients.[38]

Prolactin: Prolactin would be raised due to hyperprolactinemia (in hypothalamic disease or a pituitary tumor).[23]

Serum cortisol: In adrenal neoplasia, all layers of adrenal cortex may be hyperactive resulting in a Cushingoid status.

Fasting and postprandial insulin: In the presence of cutaneous markers for hyperinsulinemia, serum level of insulin should be measured to rule out hyperinsulinemia which is an important association of PCOS and independently can also play a hormonal role in acnegenesis.[21]

To confirm the source of excess androgen, one should either do an ACTH stimulation test or a dexamethasone suppression test. Ovarian source of excess androgen will fail to respond to this test, whereas the adrenal androgen level would increase following ACTH stimulation and decrease following dexamethasone suppression test.[39] Imaging studies like ultrasound ovaries (preferably performed in luteal phase) and adrenals are recommended to look for any mass or cyst and computed tomography (CT)\magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for further delineation of the mass, if there is any.

Hormonal therapy for Acne

Most of the hormonal therapies are mainly directed at suppressing ovarian or adrenal sources of androgens or blocking activation and action of androgens in sebaceous gland and probably follicular keratinocytes as well. This can be accomplished by using the following:

-

Suppressors of ovarian androgen secretion

- OCs: Estrogen, i.e., ethinyl estradiol (EE), suppresses the ovarian production of androgens by suppressing gonadotropin release from hypothalamus via a negative feedback effect. It also stimulates hepatic synthesis of SHBG and inhibits 5α reductase activity.[40] Low dose estrogen (EE 0.020-0.050 μg) is usually combined with various progestins (Levonorgesterol, Desogestrel, Norgestimate, and Gestodene) to avoid the risk of endometrial cancer associated with unopposed estrogens.[41,42] It is administered from day 1 of menstrual cycle and given in a 21 days on/7 days off regimen, for 5-6 cycles, after obtaining a negative pregnancy report.[43,44] Common side effects, which usually subside after 2-3 months, are breakthrough bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and weight gain. Less common side effects include decreased libido, melasma, and mood changes.[13] More serious side effects like stroke and heart attacks are minimal with the newer OCs. Contraindications to OCs use are pregnancy, lactation, poorly controlled hypertension, angina, complicated valvular disease, coagulation disorders, personal or family history of thrombotic disorders, severe obesity, undiagnosed uterine bleeding or estrogen-dependent neoplasm, neurological symptoms, hepatic dysfunction, etc.[13,45,46] Dermatologists can initiate an OC prescription with an advice to follow-up with a gynecologist because a physical examination, including a pelvic examination might be appropriate. Apart from the decreased androgen level, other additional benefits of OCs in acne patients are contraception, which is advised along with isotretinoin therapy, and menstrual irregularities too respond positively with OCs.[46] In a recent publication, it was stated that concomitant use of antibiotics such as tetracycline and doxycycline with OCs does not interfere with contraceptive steroid levels.[47,48] Example of few such OCs available in Indian market are Crisanta (EE 0.03 mg + Drospirenone 3 mg), Femilon (EE 0.02 mg + Desogestrel 0.15 mg), and Yasmin (EE 0.03 mg + 3 mg Drospirenone). Although the effects of OCs as monotherapy have been well established, they can be used in combination with other topical and oral therapies for acne for better results.[49]

- Cyproterone acetate (CPA): CPA is a progestational anti-androgen that also blocks androgen receptors. Overall improvement of 75-90% has been reported in patients treated with CPA 50-100 mg daily (with or without EE) prescribed for 3-6 menstrual cycles.[50,51] In India, CPA is available in combination with EE (e.g., Diane 35 containing 2 mg CPA with 35 μg EE). Side effects include menstrual abnormalities, breast tenderness and enlargement, nausea/vomiting, fluid retention, leg edema, headache, liver dysfunction, and rarely blood clotting disorders.[52]

- Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs: GnRH analogs inhibit ovarian androgen production by blocking the cyclical release of LH and FSH from the pituitary.[53] They are available as nasal sprays (to be given 2-3 times a day), e.g., Nafarelin and Buserelin, subcutaneous injections (once daily), e.g., Buserelin and Leuprolide, intramuscular depot injection (to be given monthly), e.g., Triptroelin, and monthly subcutaneous implant (to be given monthly), e.g., Leuprolin, Goserelin. Though GnRH analogs are very effective in suppressing ovarian androgen secretion, there are no published studies using GnRH analogs for acne alone and their use is limited by their high cost and menopausal symptoms including bone loss on their long-term use. In one study, they were prescribed for 6 months for PCOS patients with acne.[54] Pregnancy, lactation, and abnormal vaginal bleeding are the contraindications for GnRH therapy.[53]

-

Suppressor of adrenal androgen secretion

Glucocorticoids: Glucocorticoids in low doses can suppress the adrenal production of androgens. They are indicated in patients who have an elevated level of DHEAS associated with an 11- or 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Low-dose prednisolone (2.5-5 mg) or dexamethasone 0.25-0.75 mg nighttime dose suppress adrenal androgen production.[10,55] Adrenal suppression is a possible side effect, for which ACTH stimulation test should be done 2-3 months after initiation of therapy. Glucocorticoids may also be used in acute flare or in very severe acne for a few weeks.[5]

-

Androgen receptor blockers

- Spiranolactone: Is an androgen receptor blocker, inhibitor of 5α reductase, and aldosterone antagonist. It has not formally been approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acne, but it is often successfully used by dermatologists to treat hormone-responsive or therapy-resistant acne. It is administered in doses of 25-100 mg twice daily (e.g. Aldactone). Side effects are dose dependent and include hyperkalemia, hypotension, irregular menstruation, headache, fatigue, breast tenderness, decreased libido, etc., Because pregnancy is an absolute contraindication, as it can cause hypospadias and feminization of male fetus, its use with OCs is recommended. Response in acne can take as long as 3 months and has been prescribed in acne for as long as 24 months.[8,43,56]

- Flutamide: Is an androgen receptor blocker. It has been used in doses of 250 mg twice a day for 6 months in combination with OCs for the treatment of acne.[5,57] Fatal hepatitis is a serious side effect and warrants monitoring of liver function test.[58] And in view of feminization of male fetus, pregnancy is contraindicated during therapy, hence concomitant OCs use is beneficial.[5] But use of flutamide is limited by its side effect profile.

- Ketoconazole: Ketoconazole is an azole antifungal, but has additional antiandrogenic and anti-glucocorticoid effects when given at a higher dose (e.g. 400-800 mg for 3-6 months for acne), which inhibits Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme in steroid biosynthesis. Ketoconazole is rarely prescribed for acne because its effectiveness is weak and inhibition of biosynthesis of adrenal glucocorticoids limits its clinical utility as antiandrogen.[59] Ketoconazole therapy needs scrupulous monitoring for side effects like hepatitis, thrombocytopenia, and biochemical changes.[60,61]

- CPA: Already discussed.

5α Reductase inhibitor: Finasteride 5 mg/day is used by some dermatologists for hormone-related acne. But more studies are needed to validate its use in acne. And concomitant OCs use is recommended with this drug.[62]

Insulin sensitizer: Metformin is used, especially in acne in association with PCOS, HAIR-AN syndrome, obese patients, or biochemical evidence of hyperinsulinemia. It is usually given in a dose of 500 mg OD to BD doses to up to 2000 mg/day. There is no particular limit to duration of Metformin use in PCOS, but a lack of response within 6 months usually precludes its further use. Most side effects are dose dependent and include nausea, vomiting, and lactic acidosis.[63] Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone can also be used for similar purposes.[64] These insulin sensitizers may be used in combination with OCs or flutamide.[65]

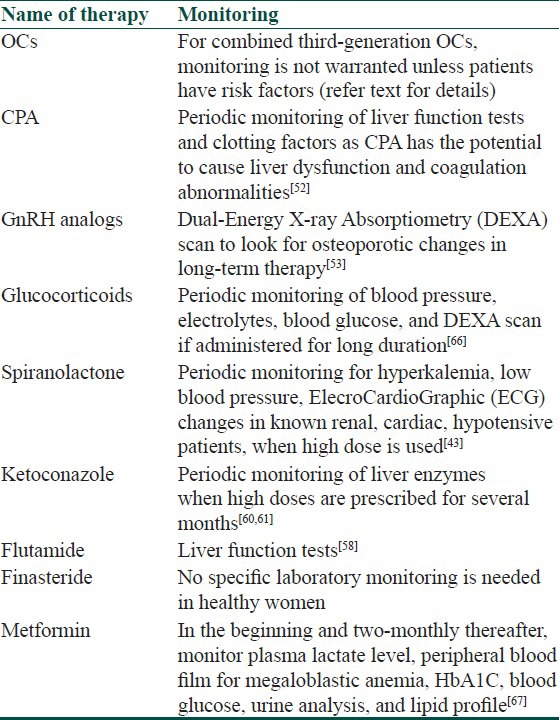

Though most of the hormonal therapeutic options available for acne are safe in healthy individuals, some of them might need monitoring of some parameters while on these therapies [Table 1].

Table 1.

Monitoring guidelines of hormonal therapy in acne

Conclusion

It is important to understand that hormonal therapy can be very effective in females with acne, whether or not their serum androgens are abnormal. Appropriate patient selection is the key to achieving good results. Hormonal therapy is useful for women with endocrine anomalies and those who have proven unresponsiveness to conventional therapies. In most cases, hormonal therapy is more successful when used in combination with other therapies including antibiotics and retinoids. From this discussion, it can be concluded that hormonal therapy is a good option for female acne patients, which is yet to gain popularity in our country. Dermatologists should become familiar with the various hormonal therapy options and their indications, contraindications, and side-effect profile, and get comfortable prescribing them as they are easily available, cost-effective, and supported greatly by literature to be beneficial for acne in women, especially for those acne patients who need oral contraception for gynecological reasons and have obvious cutaneous and biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, or those who show resistance to conventional therapies.[67]

What is new?

Scope of hormonal therapy in acne is not strictly indicated for only those having cutaneous or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, but can also be used even for conventional therapy-resistant women with acne, without hyperandrogenemia. Women with androgen receptor hypersensitivity might not have biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenemia but would benefit from anti-androgen (hormonal) therapy.

CME Questions

-

Whice of these enzymes is responsible for converting testosterone to dihydrotestosterone?

- 21α hydroxylase

- 17α hydroxylase

- 5α reductase

- 11α hydroxylase

-

Which out of these is not a cutaneous sign of hyperandrogenism?

- Androgenetic alopecia

- Acne

- Seborrhea

- Irregular menstruation

-

Which one of these drugs is an androgen receptor blocker?

- Flutamide

- Spiranolactone

- Cyproterone acetate

- Finasteride

-

Hyperkalemia is a serious side effect of which of these drugs?

- Cyproterone acetate

- Spiranolactone

- OCP

- Finasteride

-

Which of these is not a symptom of PCOS?

- Weight gain

- Irregular menstruation

- Infertility

- Hypertrichosis

-

Which is not a side effect of OCs?

- Ovarian cancer

- Weight gain

- Stroke

- Melasma

-

Which one of these GnRH analogs is used as nasal spray?

- Triptroelin

- Nafarelin

- Goserelin

- Leuprolide

-

Which enzyme is deficient in non-classical adrenal hyperplasia?

- 21α hydroxylase

- 17α hydroxylase

- 5α reductase

- 11α hydroxylase

-

Which of these hormones has a negative effect on sebum production?

- Testosterone

- Insulin

- Estrogen

- Luteinizing hormone

-

Long time use of GnRH can lead to?

- Hepatic dysfunction

- Bone loss

- Deep venous thrombosis

- Hyperkalemia

Answers

1. c, 2. d, 3. a, 4. b, 5. d, 6. a, 7. b, 8. a, 9. c, 10. b

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP. London: Martin Dunitz; 2001. Acne: Diagnosis and management; pp. 49–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson NB, Cunliffe WJ. Disorders of the sebaceous glands. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Text book of Dermatology. 7th ed. USA: Blackwell Science; 2004. pp. 43.1–43.75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.George R, Clarke S, Thiboutot D. Hormonal therapy for acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhambri S, Del Rosso JQ, Bhambri A. Pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: recent advances. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:615–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, Dreno B, Finlay A, Leyden JJ, et al. Management of acne: A report from a global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S1–38. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiboutot D. New treatments and therapeutic strategies for acne. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:179–87. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent acne: A review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spiranolactone in the treatment of acne in a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498–502. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.105557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leyden JJ. New understandings of the pathogenesis of acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pochi PE. Hormones and acne. Semin Dermatol. 1982;1:265. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pochi PE. The pathogenesis and treatment of acne. Ann Rev Med. 1990;41:187–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.41.020190.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pochi PE. Hormonal aspects of acne. J Int Postgrad Med. 1991;4:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper JC. Antiandrogen therapy for skin disease and hair disease. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eric K, Ricardo A. Ovarian hormones and andrenal androgens during a women's life span. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S105–15. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rittmaster RS. Hirsutism [review] Lancet. 1997;349:191–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenfield RL. Clinical practice. Hirsutism. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2578–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp033496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collu R, Ducharme R. Role of adrenal steroids in the initiation of pubertal mechanisms. In: James VHT, Serio M, Giusti G, Martini L, editors. The endocrine function of the human adrenal cortex. Proceedings of the Serono Symposia. Vol. 18. New York: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 547–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuster S, Thody AJ. The control and measurement of sebum secretion. J Invest Dermatol. 1974;62:172–90. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12676782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klingman AM, Shelly WB. An investigation of the biology of the human sebaceous gland. J Invest Dermatol. 1958;30:99–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pochi PE, Strauss JS. Sebaceous gland suppression with ethinyl oestradiol and diethyl stilboestrol. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:210–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL. Polycystic ovary syndrome as a form of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism due to dysregulation of androgen secretion. Endocrin Rev. 1995;16:322–53. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-3-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen W, Thibout D, Zouboulis CC. cutaneous androgen metabolism: Basic research and clinical perspective. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:992–1007. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt JB, Lindmaier A, Spona J. Hyperprolactinemia and hypophyseal hypothyroidism as cofactors in hirsutism and androgen-induced alopecia in women. Hautarzt. 1991;42:168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beylot C, Doutre MS, Beylot-Berry M. Oral Contraceptives and cyproterone acetate in female acne treatment. Dermatology. 1998;196:148–52. doi: 10.1159/000017849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Raeve L, De Schepper J, Smitz J. Prepubertal acne. A cutaneous marker of androgen excess. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:187–95. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen S, Vela P, Rankin J. Inappropriate secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone in polycystic ovarian disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1970;30:435–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem-30-4-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junkins-Hopkins JM. Hormone therapy for acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:486–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucky AW, McGuire J, Rosenfield RL, Lucky PA, Rich BH. Plasma androgens in women with acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81:70–4. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12539043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darley CR, Kirby JD, Besser GM, Munro DD, Edwards CR, Rees LH. Circulating testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin and prolactin in women with late onset or persistent acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:517–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cibula D, Hill M, Vohradnikova O, Kuzel D, Fanta M, Zivny J. The role of androgens in determining acne severity in adult women. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:399–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubba R, Bajaj AK, Thappa DM, Sharma R, Vedamurthy M, Dhar S, et al. Acne in India: guidelines for management-IAA consensus document. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(Suppl 1):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotterdam ESHRE\ASRM sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long term health risk related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belan AH, Laven JS, Tan SL, Dewally D. Ultrasound assessment of the polycystic ovary: International consensus definition. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:505–14. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbieri RL, Smith S, Ryan KJ. The role of hyperinsulinemia in the pathogenesis of ovarian hyperandrogenism. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:197–212. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cara JF, Fan J, Azzarello J, Rosenfield RL. Insulin-like growth factor-I enhances luteinizing hormone binding to rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:560–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI114745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenfield RL. Current concepts of polycystic ovary syndrome. Baillière's Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;11:307–33. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(97)80039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin-Su K, Nimkarn S, New MI. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia in adolescents: Diagnosis and management. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1135:95–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1429.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang RJ, Katz SE. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiboutot D. Endocrinilogical evaluation and hormonal therapy for difficult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:57–61. doi: 10.1046/j.0926-9959.2001.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Garner SE. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD004425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucky A, Henderson T, Olson W, Robisch DM, Lebwohl M, Swinger LJ. Effectiveness of norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol in treating moderate acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:746–54. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothman KF, Lucky AW. Acne vulgaris. Adv Dermatol. 1993;8:347–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebede TL, Arch EL, Berson D. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. Arch and Diane Berson. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, Kunz M. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: A pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George R, Clarke S, Thiboutot D. Hormonal therapy for acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neely JL, Abate M, Swinker M, D’Angio R. The effect of doxycycline on serum levels of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and endogenous progesterone. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy AA, Zacur HA, Charache P, Burkman RT. The effect of tetracycline on levels of oral contraceptives. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:28–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90617-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haroun M. Hormonal therapy of acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(Suppl 4):6–10. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Wayjen R, van den Ende A. Experience in the long-term treatment of patients with hirsutism and/or acne with cyproterone acetate-containing preparations: Efficacy, metabolic, and endocrine effects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1995;103:241–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gollnick H, Albring M, Brill K. Efficacite de l’acetate de cyproterone oral associe a l’ethinylestradiol dans le traitement de l’acne tardive de type facial. Ann Endocrinol. 1999;60:157–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammerstein J, Meckies J, Leo-Rossberg, Moltz L, Zielske F. Use of cyproterone acetate (CPA) in the treatment of acne, hirsutism, and virilism. J Steroid Biochem. 1975;6:827–36. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(75)90311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faloia E, Filipponi S, Mancini V, Morosini P, De Pirro R. Treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in acne or idiopathic hirsutism. J Endocrinol Invest. 1993;16:675. doi: 10.1007/BF03348907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cipolla L, Zagni R, Ferrante B, Giannetta G, Soliani A. Treatment with GnRH analogs in polycystic ovarian disease. A collaborative multicenter study. The preliminary results. Minerva Ginecol. 1994;46:85–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lucky A. Hormonal correlates of acne and hirsutism. Am J Med. 1995;98:89S–94S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodfellow A, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Carter G, Cream JJ, Holland S, Scully J, et al. Oral spiranolactone improves acne vulgaris and reduces sebum secretion. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:209–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adalatkhah H, Pourfarzi F, Sadeghi-Bazargani H. Flutamide versus a cyproterone acetate-ethinyl estradiol combination in moderate acne: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:117–21. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S20543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wysowski D, Freiman J, Tourtelot J, Horton M. Fatal and nonfatal hepatotoxicity associated with flutamide. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:860–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-11-199306010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sawaya ME. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, editor. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Saunders; 2007. pp. 429–30. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Venturoli S, Fabbri R, Dal Prato L, Mantovani B, Capelli M, Magrini O, et al. Ketoconazole therapy for women with acne and/or hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:335–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-2-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martikainen H, Heikkinen J, Ruokonen A, Kauppila A. Hormonal and clinical effects of ketoconazole in hirsute women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:987–91. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-5-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kohler C, Tschumi K, Bodmer C, Schneiter M, Birkhaeuser M. Effect of finasteride 5 mg (Proscar) on acne and alopecia in female patients with normal serum levels of free testosterone. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23:142–5. doi: 10.1080/09513590701214463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kazerooni T, Dehghan-Kooshkghazi M. Effects of metformin therapy on hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2003;17:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Costello M, Shrestha B, Eden J, Sjoblom P, Johnson N. Insulin-sensitising drugs versus the combined oral contraceptive pill for hirsutism, acne and risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2007;1:CD005552. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005552.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ibáñez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose flutamide-metformin therapy for hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism in non-obese adolescents and women. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:243–52. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loose DS, Stancel GM. Estrogens and progestins. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2006. pp. 1565–7. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis SN. Insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, and the pharmacology of the endocrine pancreas. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2006. pp. 1638–9. [Google Scholar]