Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common skin diseases with a complex multifactorial background. The clinical presentation, the aggravating factors and the complications vary according to the age of the patients. Most cases, approximately 60-80%, present for the 1st time before the age of 12 months. Adult-onset AD has been observed as a special variant. Pruritus is the worst sign of AD, which also often indicates an exacerbation and is considered to be the most annoying symptom of AD. Treatment is preferably started based on the severity of AD. In only 10% of the cases, AD is so severe that systemic treatment is necessary. Systemic treatment including topical wet-wrap treatment is indicated in the worst and recalcitrant cases of AD. Systemic treatment of AD is discussed with regards to the evidence-based efficacy and safety aspects. I prefer wet-wraps as a crisis intervention in severe childhood cases, whereas UV and systemic treatments are the choices in patients older than 10 years. Probiotics are not useful in the treatment. If they have any effect at all it may only be in food-allergic children with AD. Finally, anti-histamines are not effective against pruritus in AD. They are only effective against urticarial flares and in cases with food-allergy. This article consists of an expert opinion on evidence-based pharmacological treatment of AD, but it is not a systemic review.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, evidence-based dermatology, systemic treatment, topical glucocorticoids, wet-wrap treatment

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common skin diseases with a complex multifactorial pathogenesis. The diagnosis is established using the modified Hanifin-Raijka criteria as described by Williams et al.[1] The clinical presentation, the aggravating factors and the complications differ according to the age of the patients.

About 60-80% of the patients present for the 1st time before the age of 12 months. Adult-onset AD is considered to be a special variant. The worst sign of AD is pruritus, which also often indicates an exacerbation and is considered to be the most discomforting feature of AD.[2]

Treatment is started based on the severity of AD. Systemic therapy is necessary in only 10% of severe and recalcitrant AD. Scoring atopic dermatitis (SCORAD)-index or objective SCORAD or EASI evaluation are the most validated systems for evaluating the severity.[3] Follow-up of the patients may be done with easier systems such as the Three-item Severity (TIS) evaluation.[4]

Systemic therapy is warranted in those in whom the disease activity and the exacerbations cannot be controlled adequately with topical treatment regimens. In children from 6 months to 9 years one can use the wet-wrap crisis intervention therapy as a “topical” systemic therapeutic tool.[5]

Recent European Academy for Dermatology and Venereology guidelines on the treatment of AD published by Ring et al. in 2012 can be considered as a basic document.[2,6]

Topical Wet-Wrap Therapy

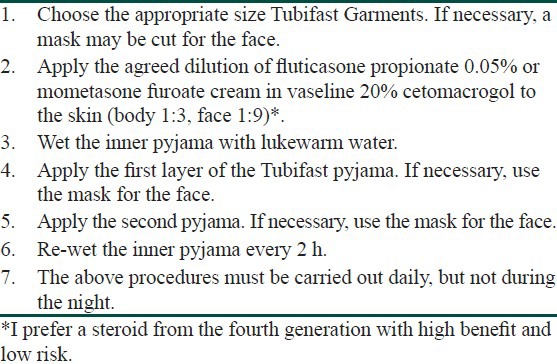

Since systemic therapy is difficult to apply on practical grounds and also because it is not patient-friendly in small children aged 6 months to 10 years, one can in fact enhance the effect of topical treatment 10-fold leading to a “systemic effect” of the therapy by means of wet-wrap. This approach should be limited to cases with severe disease intensity and extent (with an objective SCORAD of more than or equal to 40 or SCORAD-index of more than or equal to 50).[5] The use of wet-wraps with diluted corticosteroids for at least 3 days and up to 14 days is a safe crisis intervention treatment under strict controlled criteria and circumstances [Table 1]. Side-effects of relative importance are temporary systemic suppression of the adrenal glands.[7] One can apply this regimen for long-term use based on the principles of proactive treatment in which anti-inflammatory drugs are used in combination with 2-6 times daily applications of liberal amounts of emollients on the entire body.[8,9]

Table 1.

Technique of the wet-wrap method with diluted fluticasone propionate 0.05% cream (Oranje 1999, with method adaptation as described by Goodyear et al.). This involves a schedule for a clinical treatment with a duration of, in principle, 5 days

The effectiveness is partly explained by a systemic effect. This is also the reason why I have included this approach in this article.[5,8]

Cyclosporine

It was reported in two different double-blind placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that oral cyclosporine was superior to placebo.[10,11]

The efficacy of cyclosporine at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg/daily was demonstrated both in adults and in children.

Glucocorticosteroids

Except “in two small RCTs evaluating systemic glucocorticosteroids in severe childhood AD, no other data were found” in the literature by Schmitt et al. as described in their systemic review published in 2007. Especially “no data was identified for prednisolone, which is the standard systemic glucocorticosteroid used in routine clinical practice” as stated by Schmitt et al.[12] The often chosen dose of prednisone is 1-3 mg/kg/daily.

Methotrexate

MTX is very effective as an immunosuppressive drug in the treatment of several chronic inflammatory conditions. A lot of experience with MTX has been available for many years in dermatology and rheumatology.[13] It was shown to be effective, safe and without serious side-effects such as minor gastro-intestinal complaints especially in children. According to my own experience it is also very effective in AD. Dose schedule for MTX is 1 mg/m2 body surface. Goujon et al. studied MTX in 20 adults with severe AD and reported a very positive therapeutic effect.[14]

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is used for systemic treatment of AD when there are no other alternatives. It works well with good response, but it is not always well-tolerated. Leukopenia and liver function abnormalities have been reported. Treatment dose of 1.5-2.5 mg/kg/daily is used.[15] The enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase plays an important role in metabolizing the drug and deficiency of this enzyme has been associated with a high risk of myelosuppression.

Murphy and Atherton studied its effect in pediatric patients and showed that the drug also works very well in children.[16]

A study done by Schram et al. compared the efficacy and the safety of MTX and azathioprine in adults with severe AD. The drugs were equally effective, achieved significant improvement and were safe for the study-period of 12 weeks.[17]

Others

Other therapy modalities include intravenous gammaglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium. They are alternatives in resistant cases of adult AD, but enough large randomized trials are not available yet. These drugs should not be considered for routine practice.

A study done by Waxweiler et al. compared the efficacy of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil in severe AD in children. They found that both drugs were equally effective (retrospectively studied), but did show similar rates of skin infections.[18] Biologicals with enough efficacy are not available yet.[19]

Discussion

One should consider systemic treatment only when AD is non-responsive to adequate topical treatment. For children aged 6 months to 10 year, one can consider topical “systemic” treatment according to the wet-wrap method applied in a pro-active way as practiced by me since the 1990s.[5,8]

Of the systemic treatment options, cyclosporine and azathioprine are the evidence-based options, whereas MTX used by many experts still lacks enough evidence-based proof of efficacy. All the above mentioned drugs such as cyclosporine, MTX and azathioprine may be used in routine practice, with as a note to realize that cyclosporine is the ideal drug for crisis intervention with a quick response, whereas it takes at least 3 weeks before the effects of MTX and azathioprine are observed. It is important to evaluate thiopurine methyltransferase levels in monitoring azathioprine and also during the course of the treatment repeatedly.[20]

Mycophenolate and biologicals should be considered as experimental and should be used in exceptional adult cases. Intravenous gammaglobulin may also be considered as an option for cases resistant to all the drugs mentioned above and recalcitrant AD in adults.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, Archer CB, Shipley MJ, Hunter JJ, et al. The U.K. Working Party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labrèze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taïeb A. Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: Consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1997;195:10–9. doi: 10.1159/000245677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oranje AP, Glazenburg EJ, Wolkerstorfer A, de Waard-van der Spek FB. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: The SCORAD index, objective SCORAD and the three-item severity score. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:645–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janmohamed SR, Oranje AP, Devillers AC, Rizopoulos D, van Praag MCG, Van Gysel D, et al. The wet-wrap method with diluted corticosteroids versus emollients in children with atopic dermatitis: A prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.898. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oranje AP, Devillers AC, Kunz B, Jones SL, DeRaeve L, Van Gysel D, et al. Treatment of patients with atopic dermatitis using wet-wrap dressings with diluted steroids and/or emollients. An expert panel's opinion and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1277–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devillers AC, Oranje AP. Efficacy and safety of ‛wet-wrap’ dressings as an intervention treatment in children with severe and/or refractory atopic dermatitis: A critical review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:579–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darsow U, Wollenberg A, Simon D, Taïeb A, Werfel T, Oranje A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2009 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:317–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berth-Jones J, Graham-Brown RA, Marks R, Camp RD, English JS, Freeman K, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of cyclosporin in severe adult atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper JI, Ahmed I, Barclay G, Lacour M, Hoeger P, Cork MJ, et al. Cyclosporin for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: Short course versus continuous therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:52–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitt J, Schäkel K, Schmitt N, Meurer M. Systemic treatment of severe atopic eczema: A systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:100–11. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weatherhead SC, Wahie S, Reynolds NJ, Meggitt SJ. An open-label, dose-ranging study of methotrexate for moderate-to-severe adult atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:346–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goujon C, Bérard F, Dahel K, Guillot I, Hennino A, Nosbaum A, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:155–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berth-Jones J, Takwale A, Tan E, Barclay G, Agarwal S, Ahmed I, et al. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:324–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy LA, Atherton D. A retrospective evaluation of azathioprine in severe childhood atopic eczema, using thiopurine methyltransferase levels to exclude patients at high risk of myelosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:308–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schram ME, Roekevisch E, Leeflang MM, Bos JD, Schmitt J, Spuls PI. A randomized trial of methotrexate versus azathioprine for severe atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waxweiler WT, Agans R, Morrell DS. Systemic treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis with azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:689–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deleuran MS, Vestergaard C. Therapy of severe atopic dermatitis in adults. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07899_suppl.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caufield M, Tom WL. Oral azathioprine for recalcitrant pediatric atopic dermatitis: Clinical response and thiopurine monitoring. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]