Abstract

A 40-year-old lady presented with history of multiple red raised painful lesions over her body of 10 days duration. Lesions spread from forearms to arms and back of trunk during the progress of the disease. Associated pain and burning sensation in the lesions was present while working in the sun. Mild to moderate grade fever, malaise, pain over large joints, decreased appetite, and redness of eyes was also present. There was no history of drug intake or other risk-factors. Dermatological examination revealed erythematous papules coalescing to form plaques with a pseudovesicular appearance over the extensor aspect of forearms and photo-exposed areas on the back of trunk. There was a sharp cut-off between the lesions and the photo-protected areas. Investigations revealed anemia, neutrophilic leukocytosis, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and positive C reactive protein. Skin biopsy showed characteristic features of Sweet's syndrome. No evidence for any secondary etiology was found. She responded to a tapering course of oral steroids and topical broad spectrum photo-protection. This case is a very rare instance of idiopathic Sweets syndrome occurring in a photo-distributed pattern.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, neutrophils, photodistribution, Sweet's syndrome

Introduction

What was known?

Sweet's syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever, neutrophil leukocytosis, acute onset of skin lesions and histological findings of dense neutrophilic infiltrate without any evidence of primary vasculitis.

Skin lesions in idiopathic SS usually occur in a generalized distribution and respond very well to oral corticosteroids.

Sweet's syndrome (SS) was first described by Robert Douglas Sweet in 1964. The three main clinical types which are described include: Classical or idiopathic SS, malignancy-associated or paraneoplastic SS, and drug-induced SS.[1] Approximately 70% of cases are idiopathic and the paraneoplastic form is present in 10-20% associated predominantly with hematological malignancies such as acute myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and lymphoma.[2,3]

SS is characterized by fever, neutrophil leukocytosis, acute onset of skin lesions and histological findings of dense neutrophilic infiltrate without any evidence of primary vasculitis. Lesions typically involve arms, face, and trunk. We report a case of classical SS in a middle aged lady with skin lesions distributed in photo-exposed areas having a typical histopathology with therapeutic response to oral corticosteroids. Such a manifestation has very rarely been reported in literature.

Case Report

A 40-year-old lady with unknown co-morbidities presented with a 10 days history of multiple red raised painful lesions over body. Lesions were initially noted over forearms and in the next 2-3 days, new lesions appeared over arms and back. Patient complained of increased pain and burning sensation in the lesions while working in sunlight. Associated mild to moderate grade fever, intermittent in nature was present for the same duration. There was a history of malaise, pain over large joints, decreased appetite and redness of eyes. No history of oral ulcers, weight loss or any drug intake prior to her symptoms was present.

General examination revealed that she was febrile with an axillary temperature of 102°F. She also had pallor. Her systemic examination was essentially within normal limits. Dermatological examination revealed erythematous papules coalescing to form plaques with a pseudovesicular appearance over the extensor aspect of forearms and photo-exposed areas on back [Figures 1 and 2]. There was a sharp cut-off between the lesions and the photo-protected areas, where there were absolutely no lesions [Figure 3]. The plaques were tender. Conjunctival congestion was also present.

Figure 1.

Erythematous papules and plaques on extensors of forearm

Figure 2.

Close up of skin lesions showing a pseudovesicular appearance

Figure 3.

Skin lesions on back with complete sparing of the area covered by clothes (blouse)

Investigations revealed anemia with haemoglobin of 9.5 gms/dl, and neutrophilic leukocytosis with 86% neutrophils out of a total of 13,000/mm3. She had an ESR of 36 mm fall in the first hour by the Westergren's technique. C reactive protein was positive. Antinuclear antibodies ANA and ELISA for HIV were negative. Extensive radiological, biochemical and hematological investigations did not reveal any underlying malignancy or any systemic association. Skin biopsy revealed edema of the papillary dermis along with a heavy neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Furthermore, coalescing infiltrate of neutrophils in the lower dermis especially around blood vessels with absence of vasculitis was seen [Figure 4]. There was evidence of endothelial swelling with few fragmented neutrophilic nuclei but no fibrinoid necrosis [Figure 5]. She responded dramatically to a course of oral steroids in the form of Prednisolone 40 mg/day and topical broad spectrum photo-protection. Within seven days, her fever had subsided and within the next two weeks most of her skin lesions regressed. The oral steroids were tapered off in another 4 weeks. There was no recurrence of lesions after three months of follow-up.

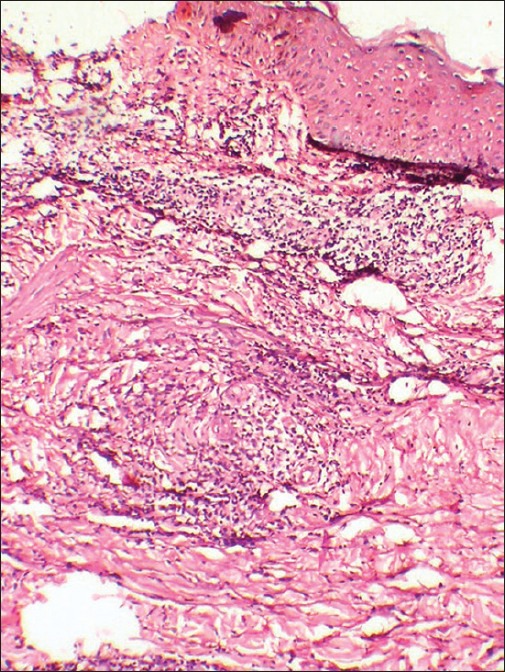

Figure 4.

Histopathology of skin lesions revealing prominent upper dermal edema with a heavy neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis and a coalescing infiltrate of neutrophils in the lower dermis especially around blood vessels with absence of vasculitis (H and E, ×10)

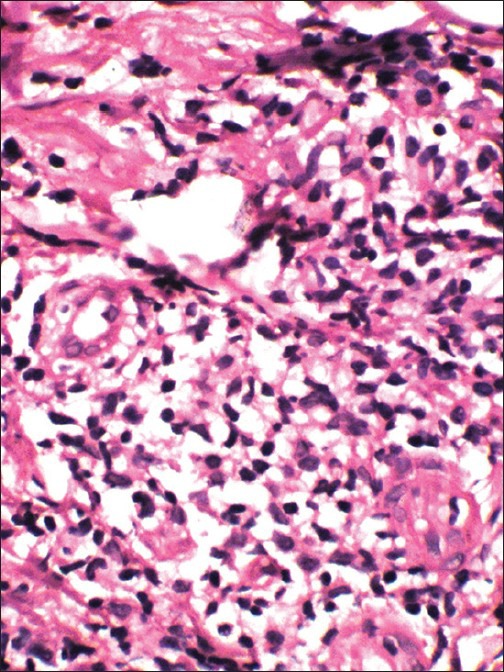

Figure 5.

Close up of the heavy neutrophilic infiltrate with some endothelial swelling and fragmented neutrophilic nuclei but no fibrinoid necrosis (H and E, ×40)

Discussion

SS is an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Diagnostic criteria for classical SS includes:

Major criteria

Abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules

Histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Minor criteria

Pyrexia >38°C

Association with an underlying hematologic or visceral malignancy, inflammatory disease, or pregnancy, or preceded by an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection or vaccination

Excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide.

Abnormal laboratory values at presentation (three of four): Erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/hr; positive C-reactive protein; >8,000 leukocytes; >70% neutrophils.

Both major criteria and two of the four minor criteria are required to establish the diagnosis of classical SS. Our patient met all, but one minor criterion and thus, is a case of classical SS.

The etiopathogenesis of SS remains unclear. Many theories regarding the etiology of SS have been proposed, including mechanical irritation, infection, dysfunctional neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, hypersensitivity, and induction by granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF).[4] Interleukin-6 (IL-6) may be elevated in SS, which may account for the clinical features of fever and pain, as well as the elevated acute-phase reactants. The relationship between IL-6 and G-CSF which can cause Sweet's is unclear; that is, do they rise in concert or does one stimulate production of the other? However, the triggering or aggravating role of UV radiation has not been mentioned as a major factor in literature.

Several medications have been associated with drug-induced SS. The most frequently incriminated drug is G-CSF; others include all-trans retinoic acid, carbemazepine, celecoxib, diazepam, diclofenac, hydralazine, levonorgestrel with ethinyl estradiol, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, propylthiouracil, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Our patient did not have any drug history prior to occurrence of symptoms.

Pathergy may be positive in SS especially at sites of cutaneous trauma induced by skin biopsies, vaccination and venipuncture. It can also occur at sites of insect bites, radiotherapy and contact dermatitis.

Drug induced SS in photo-exposed regions have been described previously.[5] There are very few previous case reports describing the worsening of idiopathic Sweet syndrome after sun exposure or photo distribution of lesions.[6,7] Lesions have also been described at site of previous phototoxic reaction.[8] The pathomechanism could involve either an isomorphic Koebner reaction, classically described in neutrophilic dermatoses, or the direct action of UV-B on neutrophil activation and recruitment in skin through the production of cytokines, such as interleukin 8 or tumor necrosis factor α.[9]

Other rare presentations of SS described include symmetrically distributed ulcerated and crusted plaques studded with bullae, lesions resembling pyoderma gangrenosum and cutis laxa following SS.[10,11]

Systemic glucocorticoids are the first line treatment for SS. Systemic symptoms and cutaneous manifestations rapidly improve after starting therapy. Our patient was treated with oral corticosteroids with a good response within few weeks. Many other treatments have been reported to be successful in SS, such as potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, dapsone, doxycycline, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil and clofazimine.[12] Without treatment, SS lesions may persist for weeks or even months, or they may eventually resolve spontaneously.

Our case highlights the concept that idiopathic SS can present as photo-dermatosis, though further investigations are required to find out the factors responsible for photo-aggravation. This case emphasizes the need of a systematic search for prior sun exposure in Sweet syndrome, especially in the so-called idiopathic forms.

What is new?

Sweet's syndrome can occur in a photodistributed pattern.

Sunlight can be a triggering factor for Sweet's syndrome and so photoprotection is important for this subset of patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome: A neutrophilic dermatosis classically associated with acute onset and fever. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:265–82. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(99)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome and malignancy. Am J Med. 1987;82:1220–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paydaº S, Sahin B, Seyrek E, Soylu M, Gonlusen G, Acar A, et al. Sweet's syndrome associated with G-CSF. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:191–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb08668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuss-Borst MA, Müller CA, Waller HD. The possible role of G-CSF in the pathogenesis of Sweet's syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;15:261–4. doi: 10.3109/10428199409049722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: Case report and review of drug-induced Sweet's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918–23. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horio T. Photoaggravation of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome) J Dermatol. 1985;12:191–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1985.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, Augias D, Guilhou JJ. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1106–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belhadjali H, Marguery MC, Lamant L, Giordano-Labadie F, Bazex J. Photosensitivity in Sweet's syndrome: Two cases that were photoinduced and photoaggravated. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:675–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strickland I, Rhodes LE, Flanagan BF, Friedmann PS. TNF-alpha and IL-8 are upregulated in the epidermis of normal human skin after UVB exposure: Correlation with neutrophil accumulation and E-selectin expression. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:763–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma SB. Recurrent Bilaterally Symmetrical Bullous Sweet's Syndrome: A Rare and Confusing Entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:483–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.103070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan M, Phiske M, Jerajani HR, Dhurat R. Sweet's syndrome leading to acquired cutis laxa (Marshall's Syndrome) in a child. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:134–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome revisited: A review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]