Abstract

Family-based interventions in pediatric cancer face challenges associated with integrating psychosocial care into a period of intensive treatment and escalating stress. Little research has sought input from parents on the role of interventions delivered shortly after diagnosis. This mixed-methods study obtained parents’ perspectives on the potential role of family-based interventions. Twenty-five parents provided feedback on the structure and timing of psychosocial interventions via focus groups and a questionnaire. Qualitative analyses resulted in three themes that were illustrative of a traumatic stress framework: 1) tension between focusing on child with cancer and addressing other family needs, 2) factors influencing parents’ perception of a shared experience with other parents, and 3) the importance of matching interventions to the trajectory of parent adjustment. Quantitative data indicated that parents preferred intervention within six months of diagnosis, with almost half favoring within two months of diagnosis, and the majority wanted interventions targeted to parents only. Qualitative themes highlight the importance of using a traumatic stress framework to inform the development of family-based interventions for those affected by pediatric cancer.

Keywords: pediatric cancer, oncology, psychosocial intervention, families, traumatic stress

Having a child diagnosed with cancer affects the entire family [1–4]. Parents face a number of demands including coping with the life-threatening nature of their child’s diagnosis, attending to their child’s physical status, and managing disruptions to existing family life [1]. Parents, however, are recognized as key to successful adaptation and coping [5, 6] and research supports family-based psychosocial interventions in the context of childhood illness [4, 7, 8]. Across pediatric cancer centers, evidence-based psychosocial assessments and interventions are inconsistently and infrequently delivered to families [9] due to limited institutional resources [9] and difficulty engaging families in psychosocial care during a period of heightened stress [10]. Family-based intervention research in childhood illness also has challenges [11] as randomized clinical trials (RCT) often experience difficulties with enrollment and completion of the intervention [10, 12–15]. Methods for increasing use of these services and engagement in RCTs remain underexplored. Stakeholder input from families of children with cancer may enhance intervention acceptability and feasibility and facilitate care. Reflecting calls for mixed-methods approaches to improve research [16], the current study combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies with parents of children treated for cancer in order to inform future intervention efforts.

A traumatic stress framework offers a helpful approach to understanding parental responses to childhood cancer [17, 18]. An integrated model of pediatric medical traumatic stress recognizes the diagnosis of a child with cancer as a potentially traumatic event for children and family members that may lead to posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), such as intrusive thoughts or hypervigilance [18]. Most parents experience elevated distress immediately after diagnosis [3, 19, 20] and a subset continues to experience significant distress well after treatment [3, 19, 20]. Family and parental adjustment in the period immediately after diagnosis is predictive of later survivor and family adaptation [20, 21] and family-based interventions have the potential to alleviate distress among family members [22].

Three interventions to enhance family adaptation to childhood cancer have been evaluated using an RCT during active cancer treatment [10, 23, 24]. A large, multi-site trial of a maternal problem-solving intervention with mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer (2–16 weeks after diagnosis) demonstrated reduced maternal depressive symptoms and PTSS at the 3-month follow-up [24]. Notably, 25% of the mothers approached refused to participate mainly due to schedule demands and feeling overwhelmed but only 11% of those enrolled were classified as non-completers [24]. The Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program – Newly Diagnosed [SCCIP-ND; 10] combined family therapy and cognitive-behavioral approaches, required two caregivers in sessions and targeted families within two months of diagnosis. Although SCCIP-ND was rated positively by participants, only 23% of eligible families consented, with most declining due to feeling too overwhelmed, highlighting the inherent challenges of intervention research with families shortly after diagnosis [10]. Additionally, requiring two caregivers may have affected consent rates and intervention feasibility. A recent pilot study evaluated a 12-session interdisciplinary intervention for mothers of children within four months of diagnosis with reported promise in terms of acceptability, feasibility and reductions in maternal distress [23]. Specifically, 84% of parents approached enrolled in the study and 74% of participants were classified as completers with most rating the intervention highly in terms of acceptability.

The variability in experiences and recruitment challenges by these RCTs underscore the tension between the perception of need for early intervention by health care providers and the acceptability of interventions by families. No known studies have directly asked parents about the needs of families and how to best design family-based interventions in the context of childhood cancer. Stakeholder perspectives are needed in order to determine appropriate intervention approaches after diagnosis [25] that can improve child and family adaptation. The objective of this mixed-methods study with parents of children treated for cancer was to obtain their perspectives on the role and timing of psychosocial interventions for families after diagnosis in order inform future intervention research.

Method

Procedure

An institutional review board approved all study procedures.

Participant Recruitment

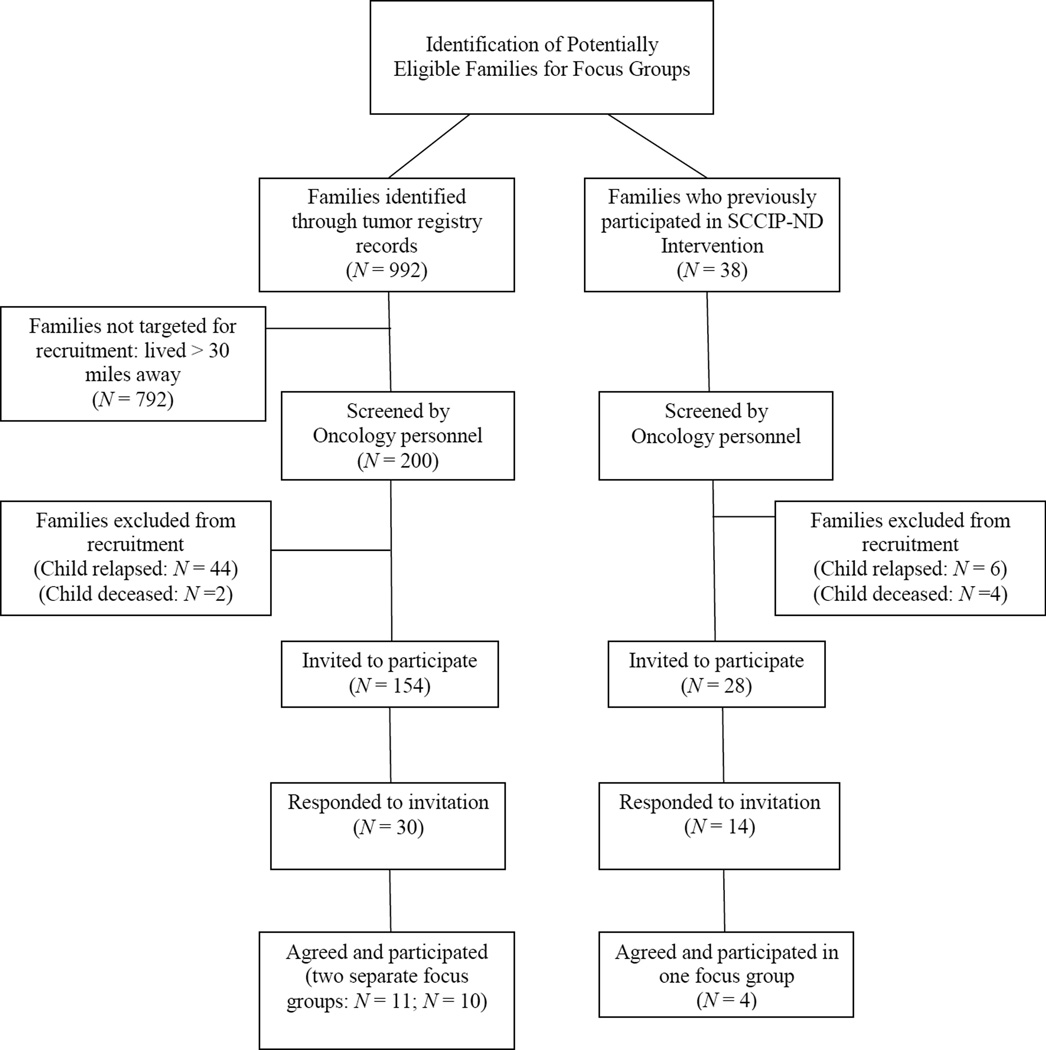

See Figure 1 for an overview of recruitment and participation. Eligibility criteria included: 1) child diagnosed with cancer 2 to 5 years prior; 2) child is alive and has not experienced a relapse; and 3) able to read and understand written and spoken English. The selected time frame since diagnosis was chosen in order to obtain variability in viewpoints and reduce the likelihood of solely capturing the acute distress experienced shortly after diagnosis. Eligible families were mailed letters inviting them to participate and received follow-up calls. In recruitment outreach, both mothers and fathers were invited to participate. Inclusive of the sample was a subgroup of parents (n = 4 parents; 3 families) who had previously completed the SCCIP-ND intervention and were recruited in order to obtain their feedback as stakeholders that opted into an RCT shortly after their child’s diagnosis. No overt differences have been noted between participants and eligible non-participants. Of note, in recruiting prior SCCIP-ND participants, 12 of 14 possible families agreed to participate, eight parents committed to the scheduled date and four participated.

Figure I.

Study Recruitment Flow.

Focus Groups

Three focus groups were conducted with each focus group following the same procedure. See Figure 1 for a breakdown of focus group sizes. Facilitators obtained written informed consent before beginning each group. Scripts (available upon request) were used to guide discussions. Questions and content of the focus groups were guided by a traumatic stress framework and attempted to explore the period following a child’s cancer diagnosis. Participants were asked to discuss a) the psychosocial needs of families after diagnosis (e.g., “What do families need during this period to help them reduce long-term distress?”), b) how an intervention might help families during this time period (e.g., “How might an intervention help? What would it do?”), c) the most appropriate timing of interventions (e.g., “When is the best time for families to participate in an intervention?”, and d) potential barriers to participating in an intervention (e.g., “What barriers might prevent your family from participating in an intervention?”). SCCIP-ND and its structure also were presented briefly as an example of an intervention. Focus group discussions lasted approximately two hours, were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Participants were provided food and refreshments during the focus groups and $50 gift cards for participating. All authors - three psychologists, one licensed counselor, one nurse, all experienced in pediatric oncology, and one parent of a child with cancer who works at the hospital as a “family faculty” member - facilitated at least one focus group after receiving training. For each focus group, two facilitators led the discussion and one took field notes.

Measures

Intervention Structure Questionnaire

At the conclusion of each focus group, participants completed an 11-item questionnaire developed for this study. The questionnaire asked about the structure and timing (e.g., “within first 2 months after diagnosis; between 3–6 months after diagnosis; after 6 months”) of psychosocial interventions for families after diagnosis, including preferred number of sessions, number of families in a session, the acceptability of technology formats, and elements that might enhance the appeal of an intervention. All items were multiple-choice and some had space to write additional comments.

Data Analyses

Qualitative Data

All focus group transcripts were uploaded into Microsoft Word. Analysis followed an established protocol [26, 27] using content analytic methods, which included a combination of both deductive and inductive approaches. The analysis treated the group as the unit of analysis and focused on identifying overall themes. Analysis proceeded from specific codes to broader categories to resultant larger themes. The content analysis was initially directed by the broad questions described above that guided each focus group [28]. The first author organized pertinent sections of the transcripts for each focus group by the guiding questions to facilitate coding [29].

A small working group (MH, JD, AK) guided the overall data management and analysis. To strengthen the scientific rigor of the analysis, teams of coders, rather than one or two total coders [30], reviewed transcript sections and coded the data using inductively-derived codes. In each team, the primary coder coded a section first and the secondary coder then reviewed the primary coder’s coding and suggested edits and/or additions to coding. The intent of this phase of the analysis was to identify a broad range of possible codes. Coders created and wrote definitions for codes as they reviewed the data. Any discrepancies in coding between coders were discussed within coding teams until a consensus was reached. The coding of each team was then reviewed by the first author to refine and condense the codes into categories. An audit trail was created in order to establish the rigor of the analysis and the interpretations and augment the treatment of the data [30, 31]. The working group (MH, JD, AK) reviewed the resultant set of coding categories and their related content in order to identify broader themes that capture the experiences of parents. Interpretation of these themes was guided by a traumatic stress framework based on the prominence of acute distress and posttraumatic stress in the content of the final set of coding categories [18]. Due to the similarities in content of the focus group with prior SCCIP participants and the other focus groups, data were combined for analysis. Given that the three focus groups offered strikingly similar data and that three to five groups are often sufficient to achieve saturation [29, 32], it was determined that saturation had been achieved.

Quantitative Data

Frequency statistics summarized participants’ responses to the Intervention Structure Questionnaire. Data for the prior SCCIP participants and non-SCCIP participants were combined due to the similarities among responses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants included 25 parents (5 fathers, 20 mothers) of 19 childhood cancer survivors. Participants were identified in the medical record as Caucasian (84%) or African-American (16%) and were representative of the patient population at the cancer center where the research was conducted. Diagnoses included leukemia (n = 8; 42.1%), solid tumor (n = 6; 31.6%), lymphoma (n = 3; 15.8%) and brain tumor (n = 2; 10.5%) and are consistent with the frequencies of childhood cancer diagnoses [33]. Survivors were, on average, 5.87 years old (SD = 3.83) at diagnosis and 10.10 years old (SD = 4.99) at the time of the focus groups. The average time since diagnosis was 4.23 years (SD = 2.71, range 2 – 13.9 years). All survivors were off-treatment at the time of the study.

Qualitative Results

Three broad themes were identified from the qualitative analysis. The themes are discussed below and presented in Table 1 with example quotes and implications for future intervention efforts. In sum, parents described the weeks after their child’s diagnosis as a period of “survival” where less immediate concerns are set aside. One parent noted that “at the moment you’re not looking beyond ‘is my child gonna see tomorrow?’ …It was survival mode. You do what you can do to get through this week.”

Table 1.

Themes from Qualitative Data.

| Theme & Definition | Example Quote | Implications for Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Tension between focusing on child with cancer and addressing other family/personal needs: difficulty in balancing need to focus all attention and energy on child with cancer versus taking care of other family/personal needs | * “I didn’t have the experience of my son [patient] going through a lot of psychological issues ‘cause he was so young. But his brother was a little older and that was a huge issue for me; I mean huge. And I was almost too busy to kind of try and pull that together myself. I did the best I could but that was a huge source of stress for my husband and me because he really had a hard time understanding what was going on.” |

|

| Perceive experience as unique and shared: degree to which parents/families status recognize shared emotional experience of having a child with cancer despite differences in experiences (based on disease, treatment protocol, etc.) | *“…no child in oncology had what my son had…they just didn’t get it. So I mean I could listen to someone whose son had leukemia, but it’s completely different ‘cause my son was at a birthday party doing the worm on the floor, and the next day he was at Children’s Hospital… Like he was sick quick and there was no one there who had that same experience and no one knew what he had.” |

|

| Match interventions to trajectory of parent adjustment: transition from survival mode to less frenetic state that allows for deeper processing of experience | *“Everybody always says “Whatever you need, just let me know.” … I don’t know what I needed at that point because I’m just like working on two hours of sleep, up all night with…throwing up and just terrible things.” *“Yeah, ‘cause when you’re at that point, when you find out your child has cancer, you’re not ready to sit down for hours and talk about… That’s wasting time.” *“Yeah, you wanna be in the room.” *“Or you could be doing something with your child to take care of your child.” |

|

Theme 1: Tension between focusing on child with cancer and addressing other family/personal needs

A notable tension related to where caregivers devote their attention was salient across all focus groups. Parents described differing abilities and desires in terms of caring for their child with cancer at the expense of personal and other family member needs. Most reported concentrating all their attention on the child with cancer and framed this as a barrier for interventions directed at parent or family adjustment. When discussing potential involvement in a parent-focused intervention one parent stated that there “was no real time for other things …because you just don’t know what tomorrow is [going to] bring.” Only after developing some sort of routine after diagnosis did parents acknowledge that they “have to start thinking about …my other child’s psychological needs.”

Theme 2: Perceive experience as unique or shared

Parents expressed variation in recognizing the emotional commonalities of having a child with cancer versus the uniqueness of their particular circumstances given their child’s specific type of cancer. This difference in perception seemed reflective of parents’ level of immersion in “survival mode” and was framed as a barrier to family-based interventions that either target all childhood cancers or combine multiple families. Parents reported difficulty looking beyond whether or not their children shared disease or treatment characteristics when talking with other parents of children being treated for cancer. Some parents indicated a belief that no one else understood their experiences due to their child’s unique medical complexities. Parents expressed a desire to connect with other parents of children with the same disease, particularly in the early period after diagnosis, in order to learn about practical matters. In describing meeting another parent farther along in treatment, one parent reported that “they knew everything and we knew nothing. It was just… It was so beneficial to have just that, just initially.” Parents acknowledged the importance of finding other parents who understood the emotional aspects of the experience of having a child diagnosed with cancer after they could better manage the practical matters of their child’s treatment. One parent indicated that talking to another parent of a child with cancer allows her “to talk about cancer, death, dying, steroid rage …without the neighbors thinking there’s something wrong with you.” Parents expressed interest in approaches that facilitate the appreciation of shared experiences.

Theme 3: Match intervention to trajectory of parent adjustment

When reflecting on potential intervention approaches, parents underscored the timing of intervention components. They indicated that intervention efforts in the immediate weeks after diagnosis should address practical issues and defer more “cerebral” issues. One parent described how “in the beginning …your head is just spinning and I feel like when you’re further down the road you’re a little more capable of thinking about cancer’s impact on the future of the family.” Another parent wanted skills to put in her “toolkit” in order to help her “daughter better because she was not a model patient.” Parents indicated that they are likely to ignore their own emotional issues early in their child’s cancer treatment and that interventions that address them too early would not be accepted. For example, when asked about their interest in attending to their own adjustment after diagnosis, one parent expressed the attitude that “I’m [going to] stick my head in the sand and pretend like it’s all [going to] go away.”

Quantitative Results

Almost half the sample (n = 12; 48%) preferred receiving intervention within 2 months after diagnosis while others (n = 9; 36%) preferred within 3 to 6 months after diagnosis or all throughout the cancer experience (n = 3; 12%). In terms of intervention structure, parents generally were split on whether to include other families (n = 13; 52%) or only their own family (n = 12; 48%) in sessions. The majority of parents preferred receiving an intervention across multiple sessions (n = 21; 84%) compared to one day-long workshop (n = 1; 4%) with others suggesting it should be implemented on an as-needed basis (n = 3; 12%). In regards to potentially acceptable technological delivery methods, parents reported a willingness to use interactive websites (n = 12; 48%), telephones (n = 10; 40%), webcams (n = 9; 36%), and internet chat rooms (n = 7; 28%) but most preferred that these technologies be used as an adjunct to in-person sessions. The majority said not to include the cancer patient in the intervention (n = 17; 68%) with some parents (n = 6; 24%) indicating that they should be included if old enough. Although some parents thought that excluding the child with cancer from sessions prevents families from participating (n = 10; 40%), most did not view it as a barrier (n = 15; 60%).

Discussion

This mixed-methods study integrates qualitative and quantitative data from parents of children treated for cancer and offers implications for future intervention efforts. Although prior studies have used qualitative methods to describe parents’ experiences [34], no known studies have used mixed-methods to obtain input directly from parents on psychosocial interventions in order to inform future interventions. Such stakeholder involvement in the development of interventions is essential to creating feasible, acceptable, and effective interventions [25].

The results of this study are complementary to the current literature and informative concerning issues that are specifically important to parents of newly diagnosed children with cancer. Although interventions generally focus on the needs of the care recipient, the importance of balancing the needs of the care recipient with those of the caregiver and family is increasingly emphasized [35–37]. While this notion may seem self-evident to health care professionals who adopt a family lens, others may not grasp the important relationships among caregiver, family, and care recipient outcomes [38]. The results support a generally flexible approach to psychosocial intervention, mindful of the needs of specific families, throughout the course of treatment.

Qualitative findings underscore the importance of considering parents’ psychological responses when developing and implementing interventions. In order to enhance acceptability, interventions should balance addressing families’ immediate needs with long-term outcomes. Quantitative data are largely complementary of the qualitative findings and illustrate the perceived need for early psychosocial intervention (i.e., within 6 months of diagnosis) and interest in using technology to facilitate engagement.

The themes that emerged from the qualitative data reflect the challenges of developing and implementing preventative psychosocial interventions during a period that is focused on “survival.” The first theme indicates that parents’ normative traumatic responses impede their ability to divert attention away from their child with cancer to other pressing or long-term needs. Therefore, interventions targeting parental functioning may have trouble engaging families thus accounting for the recruitment difficulties experienced by RCTs during this time period [10, 24]. Interventions delivered in the early period after diagnosis are sometimes necessary but should acknowledge this tension and balance addressing issues salient to the cancer patient and other family members.

Similarly, the second theme suggests that parents who are experiencing traumatic aspects of the initial treatment experience are immersed in “survival mode” and variable in terms of their ability to appreciate the shared emotional experience of parenting a child with cancer. Those parents having difficulty managing the demands associated with treatment, including their own distress, may struggle in moving past everyday details and process their experience at a deeper level with other parents or interventionists. Interventions that incorporate informational modules about different diagnoses and their related treatments and particular child and family stressors may enhance parents’ abilities to identify shared characteristics with other families and bolster coping. Incorporating trained parents whose children have been treated for cancer previously as interventionists also may address this need [39, 40]. Furthermore, interventions should normalize the emotional experiences for families and facilitate communication of these experiences.

Finally, the third theme suggests matching interventions, in terms of their content and targets, to the trajectory of parents’ distress and adjustment. In the earlier phases, interventions should be psycho-educational in nature, concrete, practical and directive and focused on reducing immediate distress. For example, interventions during this early stage may augment parenting skills to reduce child and parent distress during procedures. As families become more settled in the routines of treatment, interventions could incorporate elements designed to foster family growth and prevent maladaptive adjustment patterns from solidifying [10].

On the written questionnaire, the majority of parents indicated that interventions should be delivered within six months of diagnosis. However, this stands in contrast to families’ statements during the focus groups, where opinions seemed more variable, and to the less than optimal participation rates in the existing RCTs with this population during this time period [10, 23, 24]. Additionally, parents also indicated that interventions should not include the child with cancer and should focus on the parents. Parents also reported a willingness to engage in interventions that incorporate technology but expressed a preference for retaining in-person sessions. Effectively integrating interactive technologies (e.g., iPad apps) into interventions represents a promising area for future research.

In summary, these themes suggest that interventions should be flexible and tailored to the needs of parents and families based on diagnosis, distress level and time since diagnosis. Such considerations complicate the ability to simultaneously conduct “pure” RCTs to test the intervention’s efficacy and effectiveness, enhance participation in intervention research and address the needs of all families. Incorporating evidence-based psychosocial screening [41–43] may provide a solution to such a challenge as screening results could identify which families are appropriate for interventions and inform how interventions are adapted, tested and implemented. Additionally, these three themes provide context regarding traumatic stress responses (e.g., “survival mode”) of parents of children with newly diagnosed cancer that can inform everyday care and interactions with these families.

This study has some limitations that should be considered and addressed in future research. The data are retrospective and the conclusions drawn may be different with parents whose children are newly diagnosed, still on treatment or closer to the conclusion of treatment. Additionally, findings from this study may reflect participants’ hindsight rather than their actual desires during their child’s treatment. Future studies should consider obtaining stakeholder input from parents of children more recently diagnosed to broaden the information gained from this study. Although an effort was made to include families from a variety of backgrounds, the low participation rate may limit the extent to which the findings are relevant to all families. There was no effort to identify families at various risk levels and therefore interventions appropriate to a range of levels of wellbeing could not be ascertained. Collecting such data is a worthy but challenging endeavor that could provide further insight into appropriate interventions. Additionally, although some fathers participated, the sample consisted primarily of mothers. More research that includes fathers’ perspectives is needed in order to develop interventions that address their potentially unique needs. Future research with other stakeholders, such as siblings, also would be valuable. Participants completed the questionnaire at the conclusion of each focus group and their responses may have been influenced by the focus group discussions.

This study provides innovative mixed-methods data on psychosocial interventions for families after a diagnosis of childhood cancer and offers valuable implications for developing interventions. Although much of the findings of this study are taken for granted in the pediatric cancer community, this study fills an important gap in the literature by asking families specifically about their experiences and how psychosocial interventions may fit into their lives to promote adaptation. This study demonstrates the importance of seeking stakeholder input when conceptualizing and implementing intervention approaches and offers suggestions that can be incorporated into intervention development for this population.

Acknowledgements

Author Note: This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA 128805). The authors thank Melissa Alderfer, Ph.D., Moriah Brier, B.S., and Marissa Cummings, M.D. for their contributions to the qualitative data analysis and all those who participated in this study. The authors also thank the members of the Writers Seminar of The CHOP/PENN Mentored Psychosocial Research Curriculum for reading and reviewing prior drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Matthew C. Hocking, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Anne E. Kazak, The University of Pennsylvania and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Stephanie Schneider, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Darlene Barkman, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lamia P. Barakat, The University of Pennsylvania and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Janet A. Deatrick, The University of Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Alderfer M, Kazak A. Familial issues when a child is on treatment for cancer. In: Brown RT, editor. Comprehensive Handbook of Childhood Cancer and Sickle Cell Disease: A Biopsychosocial Approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderfer MA, Labay L, Kazak AE. Does posttraumatic stress apply to siblings of childhood cancer survivors? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;21:281–286. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolgin MJ, et al. Trajectories of adjustment in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A natural history investigation. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:771–782. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazak AE. Families of chronically ill children: A systems and social-ecological model of adaptation and challenge. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:25–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiese BH. Introduction to the special issue: Time for family-based interventions in pediatric psychology? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:629–630. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazak AE, Simms S, Rourke MT. Family systems practice in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:133–143. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallander JL, Varni JW. Adjustment in children with chronic phyical disorders: Programmatic research on a disability-stress coping model. In: La Greca AM, editor. Stress and coping in child health. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. pp. 279–297. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin AL, Foster SL. Negotiating parent-adolescent conflict: A behavioral family systems approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selove R, et al. Psychosocial services in the first 30 days after diagnosis: Results from a web-based survey of Children's Oncology Group (COG) member institutions. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2012;58:435–440. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stehl ML, et al. Conducting a randomized clinical trial of an psychological intervention for parents/caregivers of children with cancer shortly after diagnosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:803–816. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drotar D. Comentary: Involving families in psychological interventions in pediatric psychology: Critical needs and dilemmas. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:689–693. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wade SL, Carey J, Wolfe CR. An online family intervention to reduce parental distress following pediatric traumatic brain injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:445–454. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barakat LP, et al. A family-based randomized controlled trial of pain intervention for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2010;32:540–547. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e793f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaslow NJ, et al. The efficacy of a pilot family psychoeducational intervention for pediatric sickle cell disease (SCD) Families, Systems, & Health. 2000;18:381–404. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wysocki T, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes: Maintenance of effects on diabetes outcomes in adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:555–560. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell JW, et al. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuber M, et al. Is posttraumatic stress a viable model for understanding responses to childhood cancer? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinics of North America. 1998;7:169–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazak A, et al. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:343–355. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazak AE. Implications for survival: Pediatric oncology patients and their families. In: Bearison DJ, Mulhern RK, editors. Pediatric psychooncology: Psychological perspectives on children with cancer. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Best M, et al. Parental distress during pediatric leukemia and parental posttraumatic stress symptoms after treatment ends. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;26:299–307. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupst MJ, et al. Family coping with pediatric leukemia: Ten years after treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20(5):601–617. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak AE, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:493–504. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullins LL, et al. A clinic-based interdisciplinary intervention for mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37:1104–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahler OJZ, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abma TA, Nierse CJ, Widdershoven GAM. Patients as partners in responsive research: Methodological notions for collaborations in mixed research teams. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:401–415. doi: 10.1177/1049732309331869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreuger D, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruff CC, Alexander IM, McKie C. The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(4):522–537. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan DL. The focus group guidebook, focus group kit. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howlader N, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long KA, Marsland AL. Family adjustment to childhood cancer: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:57–88. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chesla CA. Do family interventions improve health? Journal of Family Nursing. 2010;16:355–377. doi: 10.1177/1074840710383145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northouse L, et al. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knafl KA, et al. Patterns of family management of childhood chronic conditions and their relationship to child and family functioning. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.03.006. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Care IfFC. Partnering with patients and families: A mini toolkit. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ireys HT, et al. Maternal outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a communitybased support program for families of children with chronic illnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:771–777. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.7.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chernoff R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illness: Pediatric outcomes. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:533–539. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazak AE, et al. Screening for psychosocial risk at cancer diagnosis: The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2011;33:289–294. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31820c3b52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kazak AE, et al. Association of psychosocial risk screening in pediatric cancer with psychosocial services provided. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:715–723. doi: 10.1002/pon.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pai ALH, et al. The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0): Psychometric properties of a screener for psychosocial distress in families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:50–62. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]