Abstract

Objective

Proactive swallowing therapy promotes ongoing use of the swallowing mechanism during radiotherapy through 2 goals: eat and exercise. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the independent effects of maintaining oral intake throughout treatment and preventive swallowing exercise.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Patients

The study included 497 patients treated with definitive radiotherapy (RT) or chemoradiation (CRT) for pharyngeal cancer (458 oropharynx, 39 hypopharynx) between 2002 and 2008.

Main Outcome Measures

Swallowing-related endpoints were: final diet after RT/CRT and length of gastrostomy-dependence. Primary independent variables included per oral (PO) status at the end of RT/CRT (nothing per oral [NPO], partial PO, 100% PO) and swallowing exercise adherence. Multiple linear regression and ordered logistic regression models were analyzed.

Results

At the conclusion of RT/CRT, 131 (26%) were NPO, 74% were PO (167 [34%] partial, 199 [40%] full). Fifty-eight percent (286/497) reported adherence to swallowing exercises. Maintenance of PO intake during RT/CRT and swallowing exercise adherence were independently associated (p<0.05) with better long-term diet after RT/CRT and shorter length of gastrostomy dependence in models adjusted for tumor and treatment burden.

Conclusions

Data indicate independent, positive associations between maintenance of PO intake throughout RT/CRT and swallowing exercise adherence with long-term swallowing outcomes. Patients who either eat or exercise fare better than those who do neither. Patients who both eat and exercise have the highest return to a regular diet and shortest gastrostomy dependence.

Keywords: Dysphagia, Prevention, Radiation, Oropharynx Cancer, Hypopharynx Cancer

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of pharyngeal cancer is rising, with 13,930 new cases projected in the United States in 2013.1 A majority of patients with locally advanced pharyngeal cancer are treated with curative radiotherapy (RT) or chemoradiotherapy (CRT), the primary goals of which are locoregional control and functional organ preservation. Dysphagia is a common effect of nonsurgical organ preservation, with an estimated prevalence of 39% to 64% after RT or CRT.2,3 Swallowing function can be adversely impacted by radiation-associated edema, fibrosis, and neuropathy. These normal tissue toxicities ultimately impair the range of motion of critical laryngeal and pharyngeal musculature, collectively referred to as dysphagia-aspiration-related structures (DARS),4 disrupting pharyngeal bolus transit and airway protection. Dysphagia significantly increases the risk of health problems after treatment.5 In severe cases of radiation-associated dysphagia (RAD), dietary restrictions and malnutrition necessitate lifelong gastrostomy dependence and chronic aspiration poses risk for potentially life-threatening pneumonia. Even in the era of conformal radiotherapy delivery for pharyngeal cancer, rates of chronic gastrostomy after RT and CRT range from 5% to 12%,6–8 and 11% of patients develop pneumonia after therapy.9,10

Proactive swallowing therapy, supported by observational studies and randomized trials, has become routine care at many institutions.8,10–16 Acute toxicities of RT and CRT including mucositis, salivary dysfunction, and dysgeusia make eating difficult. As a consequence, many patients require gastrostomy tube placement and dietary restrictions, such as avoidance of solid foods, during the course of RT or CRT. Limitations in oral intake lessen the normal resistive load on the swallowing mechanism, and prompt disuse atrophy. Disuse encourages adverse remodeling of aerodigestive tract muscles that likely exacerbates the effects of radiation-associated edema and fibrosis.17,18 Thus, the central premise of proactive swallowing therapy is "Use it or Lose it" to mitigate muscular wasting and remodeling that occurs after even brief intervals of disuse. Proactive swallowing therapy encourages ongoing use of the swallowing musculature during treatment by: 1) avoiding NPO intervals, and 2) adhering to swallowing exercise. The benefits of these distinct swallowing goals (eat and exercise) are reported in separate studies,8,10–16 but independent effects are unclear. The purpose of this study was to examine the independent effects of maintenance of oral intake (eat) and swallowing exercise adherence (exercise) during RT or CRT for pharyngeal cancers.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study of patients treated with definitive RT or CRT for pharyngeal cancer. Eligible cases were selected from 659 consecutive patients with oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal primary tumors of any histology treated with definitive RT (± chemotherapy) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between January, 2002 and December, 2008. One hundred sixty-two patients were excluded from this analysis per the following criteria: palliative RT, postoperative RT, dose <66Gy, or incomplete tumor response. Thus, 497 patients were included in this analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Proactive Swallowing Therapy

Proactive swallowing therapy advocates maximal use of the swallowing musculature throughout RT and CRT. At our institution, patients receiving definitive RT or CRT are referred to Speech Pathologists as standard of care prior to treatment for baseline evaluation and initiation of proactive swallowing therapy. Two swallowing goals are outlined for each patient guided by findings of swallowing examinations: eat and exercise. Speech pathologists prescribe a standard swallowing exercise regimen targeting hyolaryngeal excursion, airway protection, and tongue base retraction. Specific exercises prescribed during the period reviewed included a modified Shaker, jaw stretch, supraglottic/valsalva, falsetto, lingual protrusion/retraction, yawn, gargle, Masako, and effortful swallows.19 As a component of routine follow-up during and after RT or CRT, patients are asked to demonstrate competency with swallowing exercises to the speech pathologist and report their adherence to daily exercise. These details are recorded in the medical record by the speech pathologist. Speech pathologists also prescribe individualized dietary modifications or swallowing compensations when needed to facilitate safe oral intake (i.e., minimize aspiration) throughout RT and CRT. Gastrostomy tube practices in this cohort and rates of long-term dependence have been thoroughly described and examined in previous publications.8,14 Prophylactic gastrostomy tubes are not placed routinely at our institution, rather gastrostomy tubes are placed when clinically indicated based on the nutritional status and ability to safely maintain an oral diet.

Independent Variables

The primary independent variables were: 1) PO status at the end of RT/CRT (“eat”), and 2) self-reported swallowing exercise adherence (”exercise”). PO status was defined as: NPO (nothing by mouth, fully g-tube dependent), partially PO (tube feeding supplemented by consistent daily oral intake), or fully PO (100% oral intake, regardless of dietary level). Patient’s self-reported swallow exercise adherence was taken by chart abstraction. Patient’s reporting any (partial <4x/day or full ≥4x/day, per institutional protocols) exercise adherence were coded “adherent”, and those who reported no swallowing exercise or did not keep their speech pathology appointment for exercise training (i.e., those who never saw the speech pathologist) were coded as “non-adherent.” To explore interactions of eat and exercise, patients were further stratified into 6 subgroups based on their swallowing status during RT or CRT as shown in Table 1. Specific between-group comparisons were explored as follows: effect of exercise (versus no exercise) holding eat constant (NPO, partial PO, full PO), effect of partial PO (versus NPO) holding exercise constant (no exercise, exercise), and effect of full PO (versus partial PO) holding exercise constant (no exercise, exercise). Comparisons were also explored between those patients who maintained partial PO (tube+PO) compared with those who had no tube but restricted PO diets (liquid or pureed food only).

Table 1.

Swallowing during RT and CRT

| “Eat” | “Exercise” |

|

|---|---|---|

| (PO end RT/CRT) | Non-Adherent | Adherent |

| NPO | 66 (13%) | 65 (13%) |

| Partially PO | 64 (13%) | 103 (21%) |

| Fully PO | 81 (16%) | 118 (24%) |

Dependent Variables

Two swallowing-related endpoints were examined: last diet level after RT or CRT, and length of gastrostomy dependence. Diet level was defined by chart abstraction at 6–12 and 18–24 months follow-up as: NPO, tube feeds + PO, liquid or pureed, soft, or regular. A regular diet was defined by no restriction of oral intake, and no special preparation of foods such as blending or chopping solids. The latest diet rating was coded for analysis. Length of gastrostomy was calculated from date of insertion to date of removal.

Clinical Variables

Demographic and treatment data were extracted from the electronic medical record. Data points included demographic characteristics, tumor site, tumor staging according to TNM classification, and treatment history. The primary treatment modality was reviewed including method of radiotherapy (conventional 3D conformal fields or intensity modulated radiotherapy [IMRT]), radiotherapy fractionation schedule (standard or accelerated), total radiotherapy dose (Gy), number of fractions, timing of chemotherapy (none, induction, concurrent), and agent. Detailed descriptions of this cohort have been previously published, along with predictors of gastrostomy placement and duration of gastrostomy dependence.8,14

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Bivariate associations were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical outcomes (diet level) and t-tests for continuous outcomes (length of gastrostomy dependence). Multivariable ordered logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate independent effects of eat and exercise on diet levels after RT or CRT, as coded above. Multiple linear regression models were analyzed to assess independent effects of eat and exercise on length of gastrostomy dependence. Multivariable models were adjusted for clinically significant confounders including T-classification, N-classification, tumor subsite, therapeutic combination, age, and baseline (pre-RT or CRT) diet using stepwise backwards elimination. Final multivariable models retained confounders that were independently associated (p<0.05) with eat and exercise. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA data analysis software, version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Four hundred ninety-seven patients met eligibility criteria for this analysis. The median age was 56 years (range 38–80), and 87% were male. The vast majority of patients had oropharyngeal primary tumors; most had node-positive disease (81% ≥N2). T-classification was fairly evenly distributed. Most patients (452/497, 91%) were treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), and 121 (24%) were treated on accelerated (concomitant boost) fractionation radiotherapy schedules. Seventy-seven percent of patients (381/497) received systemic therapy, most often delivered concurrently (234/497, 47%) with radiotherapy. Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics

| No. (%) of Pts | |

|---|---|

| Subsite | |

| Oropharynx | 458 (92%) |

| Hypopharynx | 39 (8%) |

| T-classification | |

| 1 | 98 (20%) |

| 2 | 170 (34%) |

| 3 | 129 (26%) |

| 4 | 100 (20%) |

| N-classification | |

| N0 | 31 (6%) |

| N1 | 55 (11%) |

| ≥N2 | 370 (81%) |

| NX | 5 (1%) |

| RT technique | |

| IMRT | 452 (91%) |

| 3D conformal | 45 (9%) |

| RT schedule | |

| Standard | 376 (76%) |

| Concomitant boost | 121 (24%) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| None | 116 (23%) |

| Induction | 69 (14%) |

| Concurrent | 234 (47%) |

| Induction + concurrent | 78 (16%) |

| Gastrostomy placed | |

| No | 184 (37%) |

| Yes | 313 (63%) |

Swallowing During RT or CRT: Eat and Exercise

Seventy-four percent (366/497) of patients maintained at least some PO intake throughout RT or CRT. At the conclusion of RT or CRT, 131 patients (26%) were NPO, 167 (34%) were partially PO, and 199 (40%) were fully 100% PO. Among 199 patients who maintained full PO intake at the end of treatment, 87 ate only pureed or liquid diets and 112 ate masticated foods. Three-hundred eighty (76.4%) of patients were seen by speech pathologists before or during RT and CRT. Fifty-eight percent (286/497) of all patients reported exercise adherence, 128 >4x per day and 158 ≤4x per day. Patients were further stratified into 6 swallowing subgroups per the interaction of eat and exercise as shown in Table 1. Of the 2 swallowing goals (eat and exercise), only 13% of patients did neither, 64% met some swallowing goals with at least partial PO intake and/or exercise adherence, and 24% met both goals with full PO intake throughout treatment and swallowing exercise adherence.

Long-term Diet Outcomes

Overall, 402 (81%) patients returned to a regular diet after RT or CRT. Greater proportions of patients who maintained PO intake throughout RT/CRT and/or performed swallowing exercise maintained a regular diet in long-term survivorship (p=0.012, median follow-up: 22.2 months, IQR: 17.8–24.2). Dose-response effects were suggested on subgroup analyses, as illustrated in Table 3 and Figure 1. By adherence to swallowing goals during treatment, the proportion of patients returning to a regular diet after RT/CRT was: 65% of patients who did neither (no eat nor exercise), 77% to 84% who maintained some swallowing goals (eat and/or exercise), and 92% of patients who met both swallowing goals (eat and exercise). Thus, only 65% of patients who were NPO during RT/CRT and non-adherent returned to a regular diet after treatment compared with 92% of patients who maintained maximal swallowing activity during treatment (full PO and swallowing exercise adherence).

Table 3.

Outcomes (long-term diet & gastrostomy duration) by Swallowing Subgroups

| “Eat” | “Exercise” |

|

|---|---|---|

| (PO end RT) | Non-adherent | Adherent |

| NPO | 43 (65%) | 51 (79%) |

| 222 (33–1781) | 151 (37–1530) | |

| Partial PO | 49 (77%) | 83 (81%) |

| 157 (38–760) | 111 (0–2029) | |

| Full PO | 68 (84%) | 108 (92%) |

| 0 | 0 | |

Cells display:

n (%) PO regular diet after RT/CRT

median (range) days PEG

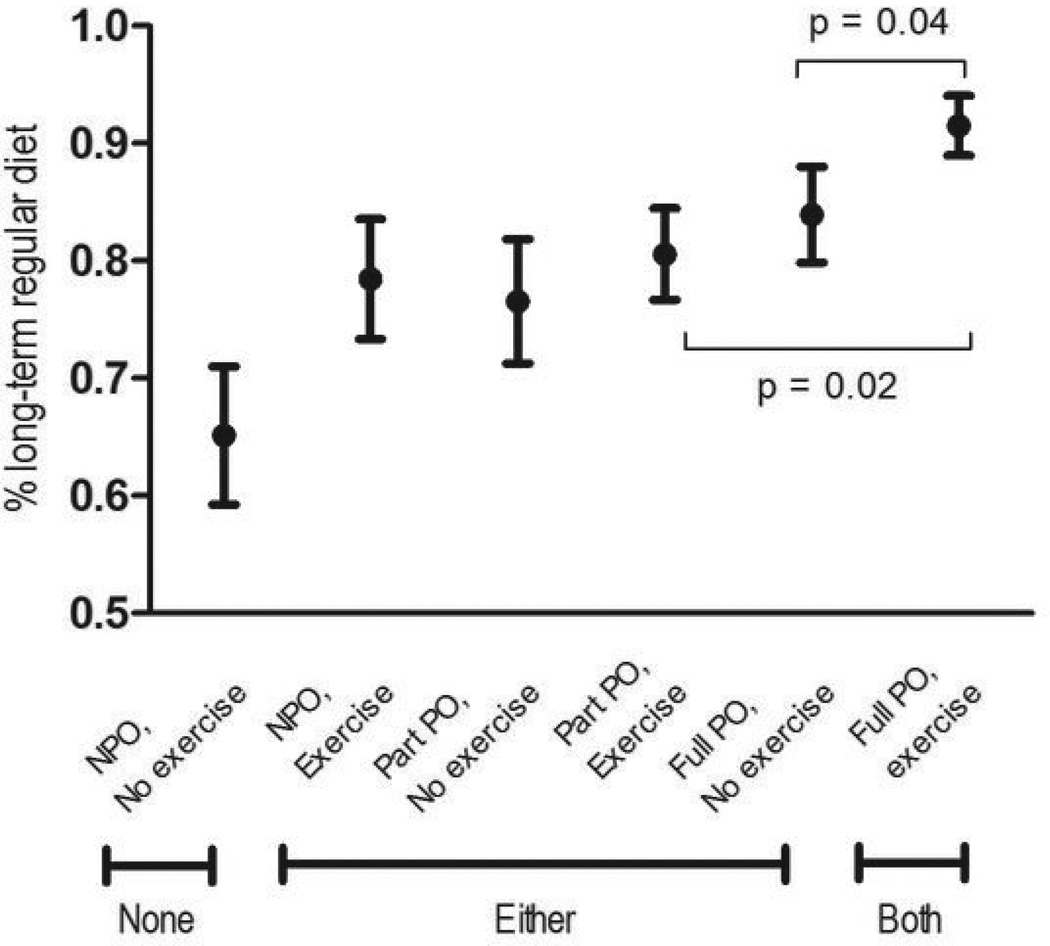

Figure 1.

Long-term Diet by Swallowing Groups

Greater proportions of patients who performed swallowing exercise and/or maintained PO intake throughout treatment ate a regular diet after RT or CRT (p=0.012).

Abbreviations: NPO, nothing per oral, PO, per oral

Specific between-group comparisons revealed statistically significant difference in long-term diet by the following stratifications: 1) full PO versus partial PO (p=0.02) among patients who adhered to exercise, and 2) exercise versus no exercise among patients who maintained full PO (p=0.04). Among patients who did not exercise, PO status at end of RT was not significantly associated with long-term diet (p>0.05). In addition, patients who maintained a restricted PO diet of pureed or liquids during RT or CRT without tube were more likely to return to a regular diet (76/87, 87%) than those on tube feedings supplemented with partial PO (132/167, 79%, p=0.191).

In adjusted models, both swallowing goals (eat and exercise) were independently associated with long-term diet levels (p<0.05). Patients who maintained full PO intake during RT/CRT were 2.0-times more likely to eat a regular diet in long-term follow-up (ORadjusted 2.0, 95% CI: 1.0–4.6) compared with those who were NPO during treatment. Swallowing exercise adherence was associated with 4.0-times the odds of a returning to a regular diet in adjusted models (ORadjusted 4.0, 95% CI: 1.9–6.4). Multivariable regression analyses are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariable models: Long-term diet & gastrostomy duration by Eat & Exercise

| Length PEG dependence |

Diet after RT/CRT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days PEG* median (range) |

Coefficient (95% CI) |

p | Regular diet† n (%) |

Adjusted odds-ratio (95% CI) |

p | |

| “Eat” | ||||||

| (PO end RT) | ||||||

| NPO | 183 (0–1716) | 94 (73%) | ||||

| Partial PO | 120 (0–2029) | −95.4 (−143.7, −47.1) | <0.001 | 132 (79%) | 1.2 (0.8, 2.9) | 0.227 |

| Complete PO | 176 (88%) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.6) | 0.045 | |||

| “Exercise” | ||||||

| Non-adherent | 113 (0–1594) | 160 (76%) | ||||

| Adherent | 68 (0–1815) | −106.0 (−182.8, −29.2) | 0.007 | 242 (85%) | 4.0 (1.9, 6.4) | <0.001 |

Model adjusted for T-classification, age, and baseline diet

Model adjusted for T-classification, tumor site, age, and baseline diet

Gastrostomy Duration

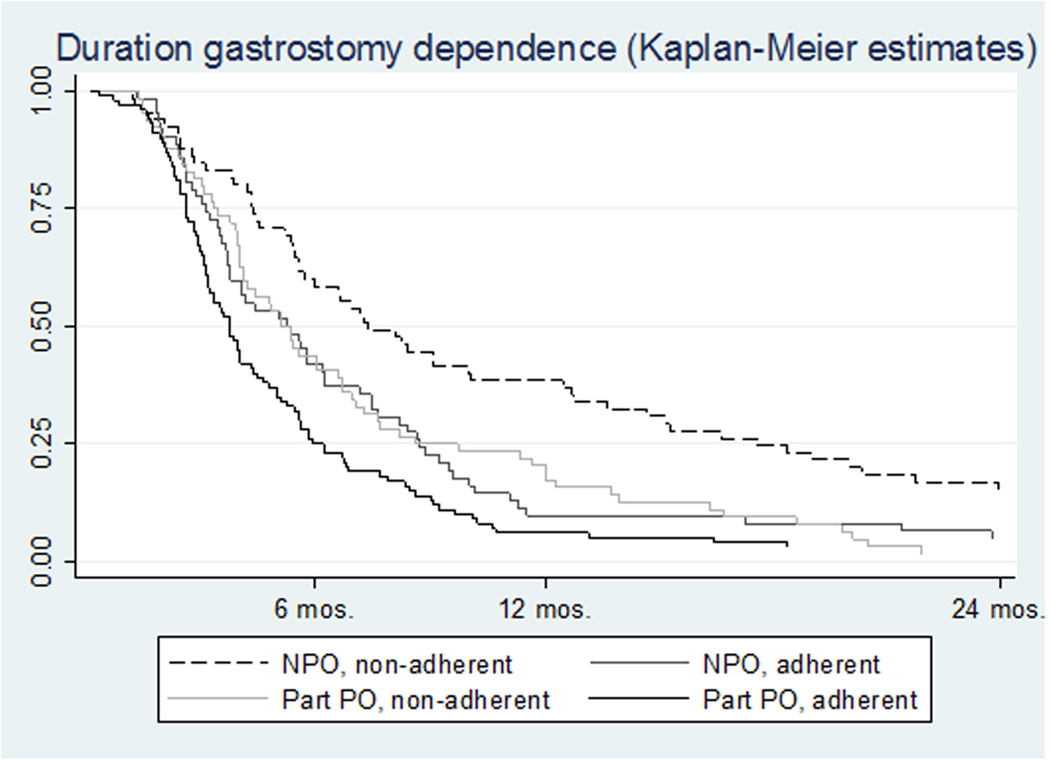

Three hundred thirteen patients (63%) received a gastrostomy tube, and the median duration of gastrostomy dependence was 5.0 months (IQR: 2.8–8.8). Swallowing during RT or CRT (eat and exercise) was associated with significantly shorter duration of gastrostomy dependence (p=0.03), and dose-response effects were suggested in subgroup analyses (Table 3 and Figure 2). Among the 313 patients who required gastrostomy placement, median gastrostomy duration was: 222 days in patients who did neither (no eat nor exercise), 151–157 days in patients who maintained some swallowing (eat and/or exercise), and 111 days in patients who did both eat and exercise. Thirty-nine percent of patients who were NPO and non-adherent to swallowing exercise were gastrostomy dependent for 1 year compared with only 6% who maintained some PO intake throughout treatment and performed swallowing exercises. Kaplan-Meier estimates are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Gastrostomy Duration by Swallowing Groups

Among the 313 patients who received a g-tube, exercise adherence and maintenance of some PO intake at the end of treatment was associated with significantly shorter duration of gastrostomy (p=0.03)

Abbreviations: NPO, nothing per oral, PO, per oral

In adjusted models adjusted, both swallowing goals (eat and exercise) were independently associated with gastrostomy duration (p<0.05). On average, gastrostomy duration was 95 days shorter among patients who maintained PO intake during treatment and 109 days shorter among those who reported adherence to exercise, based on regression coefficients in adjusted multivariable models. Multivariable regression results are provided in Table 4. Univariable analyses for adjustment variables associated with long-term diet and gastrostomy duration are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Adjustment Variables Associated with Long-term Diet & Gastrostomy Duration

| Days PEG | Regular diet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of pts | Median (range) | p | n (%) | p | |

| Age | |||||

| <50 | 95 | 50 (0 | 83 (87%) | ||

| 50–59 | 211 | 71 (0 | 180 (85%) | ||

| 60–69 | 130 | 110 (0 | 99 (76%) | ||

| ≥70 | 61 | 122 (0 | 0.003 | 40 (66%) | 0.001 |

| Subsite | |||||

| Oropharynx | 458 | 75 (0 | 385 (84%) | ||

| Hypopharynx | 39 | 92 (0 | 0.971 | 17 (44%) | <0.001 |

| T-classification | |||||

| 1 | 98 | 0 (0 | 93 (95%) | ||

| 2 | 170 | 64 (0 | 152 (89%) | ||

| 3 | 129 | 91 (0 | 97 (75%) | ||

| 4 | 100 | 169 (0 | <0.001 | 60 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Baseline diet restriction | |||||

| No | 444 | 69 (0 | 380 (86%) | ||

| Yes | 53 | 202 (0 | <0.001 | 22 (42%) | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| None | 116 | 0 (0 | 110 (95%) | ||

| Induction | 69 | 0 (0 | 64 (93%) | ||

| Concurrent | 234 | 112 (0 | 173 (74%) | ||

| Induction + concurrent | 78 | 111 (0 | 0.010 | 55 (71%) | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Swallowing is the top functional priority rated by HNC patients before and after treatment,20 and is a driver of quality of life in HNC survivors.21 Proactive swallowing therapy is prescribed to provide maximal use of the swallowing mechanism during treatment. Two goals can be given to patients under a “Use It or Lose It” paradigm: eat and exercise. The benefits of PO intake during RT and CRT (eat) and swallowing exercise adherence (exercise) have been demonstrated in separate studies,8,10–15 but to date the independent effects of these efforts have not been reported. In this study, we found that both swallowing goals – eat and exercise – were independently associated with significantly better swallowing-related endpoints. In addition, subgroup analyses suggested dose-dependent benefits. That is, these data imply that patients who either eat or exercise fare better than those who do neither, and swallowing endpoints are best among those who both eat and exercise.

Swallowing exercise during RT or CRT is associated with favorable functional outcomes. Four institutions have published outcomes of proactive swallowing exercises to date, finding superior swallowing-related QOL,10,13 better tongue base and epiglottic movement,11 lower rates of PEG placement,8,14 shorter gastrostomy dependence,8,14 and higher diet levels after therapy15 among patients who receive early swallowing exercise regimens. Among these studies, two randomized controlled trials reported favorable muscle composition on acute post-CRT MRI and significantly better clinician-rated swallowing performance (FOIS and PSSHN) in patients randomized to exercise therapy during treatment.12,15 In a sham-controlled trial, patients randomized to proactive swallow exercise were 6x more likely to have favorable swallowing outcome based on a composite endpoint of weight, diet, and standardized swallow rating. 12 Patients randomized to exercise also had a 36% absolute risk reduction for loss of functional swallowing ability during CRT.12 While these results are encouraging, authors predominantly report outcomes in early recovery within 6-months of RT or CRT, and few studies have examined outcomes more than one year post-therapy.13 In addition, prior studies have not jointly examined both domains of proactive swallowing therapy (i.e., eat and exercise) as independent constructs of swallowing behavior during treatment. In the present study, self-reported exercise adherence was associated on average with 3.5 months shorter gastrostomy dependence and 4.0 times increased odds of eating a regular oral in long-term survivorship, after adjusting for PO status during RT or CRT. In addition, we found a 58% rate of self-reported exercise adherence similar to that reported by Carnaby et al12 who found that 68% of patients adhered to home exercise. These data suggest that exercise adherence is an achievable goal for many patients despite the competing priorities and toxicities encountered during treatment.

Maintenance of PO intake, or avoidance of NPO intervals, is recommended by many practitioners largely on the basis of empirical consensus. Effects of PO intake during RT or CRT have been studied much less extensively than swallowing exercise. To date, two small retrospective observational studies have reported better swallowing outcomes in patients who maintain PO intake throughout treatment. Gillespie et al22 first reported that NPO intervals >2 weeks during CRT significantly predicted long-term post-treatment swallowing-related QOL scores (≥12-months) based on responses from the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory. Others have reported significantly better mean diet scores at 3-, 6-, and 12-month intervals among patients who maintain partial or full PO intake throughout treatment compared with patients who are NPO.23 Herein, we found that 74% of patients maintained partial or full PO intake at the conclusion of RT or CRT, similar to other investigators who reported maintenance of PO by 76% of HNC patients treated with definitive or postoperative RT or CRT.23 These data suggest that it is feasible for most patients to maintain at least some oral intake during treatment despite the acute toxicities of RT and CRT. Multidisciplinary supportive care is critical to help patients avoid NPO intervals during treatment.

Proactive swallowing therapy seeks to counteract the loss of the “normal” resistive load that occurs when the acute effects of RT or CRT cause patients to stop eating solid foods. Skeletal muscles can begin to show evidence of disuse atrophy just hours after immobilization. Myoarchitecture changes rapidly with disuse showing a decrease in muscle mass, infiltration of adipose tissue, and redistribution of fibers within the muscle. Over time, disuse atrophy manifests as a reduction in muscle strength, increased fatigability, and aberrant motor control. The extent of injury is dependent on the severity of restriction. Thus, greater use of the swallowing mechanism during radiotherapy should equate to more normal muscle composition and function after treatment.17,18 This premise is supported by prior work in which patients randomized to proactive swallowing exercise had significantly less deterioration in muscle mass and composition per T2-weighted MRI analysis of the genioglossus, hyoglossus, and mylohyoid after chemoradiation.12 In addition, results of our subgroup analyses suggested dose-dependent associations; subgroups of patients with maximal use of the swallowing mechanism during RT or CRT had the best swallowing-related outcomes.

This study benefits from a large sample size of patients with similar clinical characteristics. We have demonstrated independent, positive associations for two swallowing activities during RT and CRT - eat and exercise - in almost 500 cases of complete responders to definitive RT or CRT for pharyngeal cancers. Both early (gastrostomy duration) and long-term (diet) swallowing-related endpoints were significantly better as swallowing behaviors during RT or CRT increased between subgroups of patients. On the basis of these data, future investigations are encouraged to consider the patient’s swallowing function during RT or CRT based on PO status and exercise adherence as possible important co-variables when reporting post-radiation swallowing outcomes.

Eat and exercise, two goals commonly prescribed by speech pathologists in proactive swallowing therapy, were independently associated with favorable outcomes after adjustment for confounding markers of tumor and treatment burden. It is not likely that the referral alone to speech pathology confers benefit but rather it is the provision of and adherence to evidence-based swallowing therapy that are key to optimizing functional outcomes. In this study, swallowing outcomes did not significantly differ among the 380 patients who did and the 117 patients who did not follow-up with appointments to the speech pathologist. Referral bias inherent to observational studies and patient characteristics that influence attendance to appointments are important variables that likely influence these outcomes. These variables were not available in the present study and future evaluations are needed to understand the influence of consultation patterns and patient attendance on swallowing recovery. More important, adherence to evidence-based swallowing therapy prescribed by the speech pathologist improves outcomes and was significantly associated with better swallowing endpoints in this study. Similar to any discipline, it is not the appointment that makes the difference but the adherence to appropriate selected interventions as the patient who sees a specialist but fails to take their prescribed medication will benefit less than one who adheres.

Observational, retrospective methods employed in this study inherently limit our ability to explore detailed dose-response relationships regarding the amount of exercise or minimal PO intake necessary to confer benefit. These are important considerations for future studies, and ongoing dose-response trials may begin to answer some of these questions.24 Other important considerations are baseline performance status and acute toxicities (e.g., mucositis, odynophagia) that may likely impact patients’ ability to eat and exercise during treatment. These factors were not available in this retrospective dataset, but should be examined in prospective studies to ensure that the effects observed in this analysis are not merely a reflection of poorer performance status or greater acute toxicity that preclude swallowing activity during RT or CRT. In addition, adherence data were not prospectively measured and relied on abstraction from the medical record. If adherence details were not completely documented in the medical record, a loss of statistical power may have resulted in overly conservative estimates of associations in our analyses. As such, it is possible that future investigations that prospectively ascertain functional status during RT or CRT might show larger differences in outcomes associated with eat and exercise. Finally, further study is needed also to examine long-term physiologic effects of these swallowing goals during RT and CRT using gold-standard modified barium swallow studies, and the influence of these swallowing practices on outcomes in other sites of head and neck cancer, such as the larynx.

Conclusions

Long-term swallowing outcomes were best in patients who maintained both 100% PO throughout RT or CRT and reported adherence to swallowing exercises, and uniformly worst in those who were NPO at the end of treatment and non-adherent to exercise. Multivariable models show independent effects of two swallowing goals – eat and exercise - and subgroup analyses suggest additive effects of eat and exercise. Proactive swallowing therapy that facilitates safe PO intake throughout RT and CRT and swallowing exercise adherence should be considered an essential component of modern, multidisciplinary head and neck care. Our findings, in concert with prior rigorous trials, offer support for early referral to the speech pathologist to begin proactive swallowing therapy before definitive RT or CRT.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the UT Health Innovation for Cancer Prevention Research Fellowship, The University of Texas School of Public Health – Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant #RP101503 (K.A.H).

The authors thank Ms. Janet Hampton for help in preparation of the manuscript, and Ms. Clare P. Alvarez, Ms. Denise A. Barringer, and Ms. Asher Lisec for contributions to data collection.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Head and Neck Society 2013 Meeting at the Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meeting, April 10-11, 2013, Orlando, FL.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caudell JJ, Schaner PE, Meredith RF, et al. Factors associated with long-term dysphagia after definitive radiotherapy for locally advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(2):410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis DO, Weymuller EA, Jr, Parvathaneni U, Merati AL, Yueh B. Dysphagia, stricture, and pneumonia in head and neck cancer patients: does treatment modality matter? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119(6):391–397. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisbruch A, Schwartz M, Rasch C, et al. Dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: which anatomic structures are affected and can they be spared by IMRT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(5):1425–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter KU, Feng FY, Schipper M, et al. What is the clinical relevance of objective studies in head and neck cancer patients receiving chemoirradiation?. Analysis of aspiration in Swallow Studies Vs. Risk of Aspiration Pneumonia; Poster presented at: American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO); October, 2011; Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garden AS, Kies MS, Morrison WH, et al. Outcomes and patterns of care of patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma treated in the early 21st century. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Arruda FF, Puri DR, Zhung J, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for the treatment of oropharyngeal carcinoma: The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhayani MK, Hutcheson KA, Barringer DB, et al. Gastrostomy tube placement in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: Factors affecting placement and dependence. Head Neck. doi: 10.1002/hed.23200. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. Intensity-modulated chemoradiotherapy aiming to reduce dysphagia in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: clinical and functional results. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2732–2738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulbersh BD, Rosenthal EL, McGrew BM, et al. Pretreatment, preoperative swallowing exercises may improve dysphagia quality of life. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):883–886. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217278.96901.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll WR, Locher JL, Canon CL, Bohannon IA, McColloch NL, Magnuson JS. Pretreatment swallowing exercises improve swallow function after chemoradiation. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):39–43. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31815659b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnaby-Mann G, Crary MA, Schmalfuss I, Amdur R. "Pharyngocise": Randomized Controlled Trial of Preventative Exercises to Maintain Muscle Structure and Swallowing Function During Head-and-Neck Chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(1):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinn EH, Basen-Engquist KM, Guam G, et al. Observation of adherence patterns to preventative swallowing exercises in oropharynx cancer survivors. Head Neck. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhayani MK, Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA, et al. Gastrostomy tube placement in patients treated with hypopharyngeal cancer treated with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: Factors affecting placement and dependence. Head Neck. doi: 10.1002/hed.23199. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotz T, Federman AD, Kao J, et al. Prophylactic swallowing exercises in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiation: a randomized trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(4):376–382. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe JW, Ashforth KM. Prophylactic swallowing exercises for patients receiving radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;19(3):144–149. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283457616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasper CE, Talbot LA, Gaines JM. Skeletal muscle damage and recovery. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13(2):237–247. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark BC. In vivo alterations in skeletal muscle form and function after disuse atrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(10):1869–1875. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a645a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenthal DI, Lewin JS, Eisbruch A. Prevention and treatment of dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiation for head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(17):2636–2643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson JA, Carding PN, Patterson JM. Dysphagia after nonsurgical head and neck cancer treatment: patients' perspectives. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(5):767–771. doi: 10.1177/0194599811414506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter KU, Schipper M, Feng FY, et al. Toxicities affecting quality of life after chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer: Prospective study of patient-reported, observer-rated, and objective outcomes [published online ahead of print October 2 2012] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.08.030. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360301612034505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillespie MB, Brodsky MB, Day TA, Lee FS, Martin-Harris B. Swallowing-related quality of life after head and neck cancer treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(8):1362–1367. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langmore S, Krisciunas GP, Miloro KV, Evans SR, Cheng DM. Does PEG use cause Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients? Dysphagia. 2012;27(2):251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9360-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnaby GD, Lagorio L, Crary MA, Amdur R, Schmalfuss I. Dysphagia prevention exercises in head and neck cancer: Pharyngocise dose response study. Paper presented at: 20th Annual Dysphagia Research Society Meeting; March, 2012; Toronto, Ontario. [Google Scholar]