Abstract

Substance abuse is a major barrier in eradication of the HIV epidemic because it serves as a powerful cofactor for viral transmission, disease progression, and AIDS-related mortality. Cocaine, one of the commonly abused drugs among HIV-1 patients, has been suggested to accelerate HIV disease progression. However, the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown. Therefore, we tested whether cocaine augments HIV-1–associated CD4+ T-cell decline, a predictor of HIV disease progression. We examined apoptosis of resting CD4+ T cells from HIV-1–negative and HIV-1–positive donors in our study, because decline of uninfected cells plays a major role in HIV-1 disease progression. Treatment of resting CD4+ T cells with cocaine (up to 100 μmol/L concentrations) did not induce apoptosis, but 200 to 1000 μmol/L cocaine induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Notably, treatment of CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors with both HIV-1 virions and cocaine significantly increased apoptosis compared with the apoptosis induced by cocaine or virions alone. Most important, our biochemical data suggest that cocaine induces CD4+ T-cell apoptosis by increasing intracellular reactive oxygen species levels and inducing mitochondrial depolarization. Collectively, our results provide evidence of a synergy between cocaine and HIV-1 on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis that may, in part, explain the accelerated disease observed in HIV-1–infected drug abusers.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has claimed the lives of an estimated 35 million people (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/index.html, last updated October 2013). Although anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically reduced HIV/AIDS-related mortality,1 substance use is a major barrier for combating the HIV/AIDS pandemic because it is associated with transmission, delayed diagnosis, delayed initiation of therapy, and poor adherence to therapy.2 Cocaine is a commonly abused drug among HIV-1 patients,3–5 and studies suggest that cocaine abuse may accelerate HIV-1 disease progression. For example, Vittinghoff et al6 documented an increased risk of HIV-1 disease progression among frequent cocaine users. Arnsten et al7,8 have reported that active cocaine use strongly predicts failure to viral suppression. Similarly, Webber et al9 suggested that use of cocaine, along with alcohol, might accelerate HIV-1 disease progression. In addition, Lucas and colleagues10–12 found that cocaine users have inferior virological and immunological responses to ART. The effects of cocaine on disease progression in these studies can be attributed, in part, to nonadherence to ART, because substance use is often associated with reduced adherence and/or access to ART.13 There are also reports that did not find significant association between cocaine abuse and HIV-1 disease progression.14,15 However, Baum et al3 found that cocaine users have higher viral load and were twice as likely to progress to AIDS when controlled for ART use. Notably, Palepu et al16 reported that HIV-1–positive drug users, while taking ART, were less likely to suppress the viral load. Recently, Rasbach et al17 have suggested that active cocaine use among HIV-1 patients is associated with lack of virological suppression, independent of ART adherence. Although in vitro studies suggest that increased HIV-1 replication by cocaine18–21 may play a role, the mechanism by which cocaine accelerates HIV-1 disease progression remains unclear. Therefore, we evaluated whether cocaine could potentiate HIV-1–induced CD4+ T-cell apoptosis because CD4+ T-cell decline is an important predictor of HIV-1 disease progression. Our data suggest a synergy between cocaine and HIV-1 on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis and highlight the molecular interplay between cocaine abuse and HIV-1 disease progression.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

Blood from HIV-negative individuals was purchased from the New York Blood Center (New York City, NY), as per the Meharry Medical College (Nashville, TN) Institutional Review Board. HIV-infected individuals were recruited through Institutional Review Board–approved protocols from Vanderbilt University Medical Center (Nashville). Inclusion criteria included documented HIV infection and >18 years of age. Individuals taking ART were excluded from this study. All individuals provided written informed consent.

Isolation and Treatment of CD4+ T Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated as per our published method.18,22 Resting CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by negative selection using a CD4+ T-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, and antibiotics. The purity of the cells was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), as per our published methods.18 Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). A total of 2 × 106 CD4+ T cells/mL media were seeded in culture dishes overnight at 37°C and were exposed to cocaine and/or HIV-1 virions for 24 hours. Cocaine (1 μmol to 1 mmol) was used to cover a wide range of physiological concentrations reported among cocaine addicts.23–28 The supernatants of infected ACH-2 cells were used as the source of X4 tropic HIV-1 LAI virions.18 Infectivity, viral p24 ELISA, and measurement of intracellular viral p24 were performed as per our published protocol.18 Apoptosis was measured by annexin V (AV) and propidium iodide (PI) staining using flow cytometry, as per our published methods.18,22

Measurements of ROS and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2,7-Dichlorohydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF; Sigma) was used to measure intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). After treatment, cells were centrifuged, washed with PBS, and exposed to serum-free, phenol red–free medium containing 10 μmol/L DCF for 30 minutes in the dark. After two washes, fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. In parallel, cells were solubilized with 0.5% SDS and 5 mmol/L Tris HCl (pH 7.5) and the fluorescence intensity of the lysate was determined by spectrofluorometer, with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 520 nm, respectively. Mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed by using the fluorescent dye, 5,5′,6,6′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Cayman Chemical). After treatment, cells were stained with JC-1 dye for 30 minutes at 37°C. After two washes, the cells were resuspended in buffer and the fluorescence was measured, with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485/567 and 520/620 nm, respectively.

Measurement of Apoptosis of CD4+ T Cells from HIV-Positive Individuals

We used cryopreserved PBMCs from 15 ART-naïve HIV-1–infected patients. All laboratory procedures were performed blinded to case-control status. These PBMCs were thawed, washed, and cultured, with or without cocaine for 24 hours. These cells were then washed and stained with a panel of antibody that includes staining with live/dead aqua stain, CD4, HLA-DR (immune activation marker), and CD69 (early immune activation marker). Apoptosis was measured with AV and live/dead aqua. Data were acquired by FACS and analyzed with FacsDIVA and/or Flowjo software version 7.6.5.

Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were repeated three times, with each experiment containing triplicate samples. The significance of differences between control and treated samples was determined by one-way analysis of variance. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using a Student’s t-test. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2007.

Results

Cocaine Enhances HIV-1–Induced Apoptosis of Uninfected Resting CD4+ T Cells

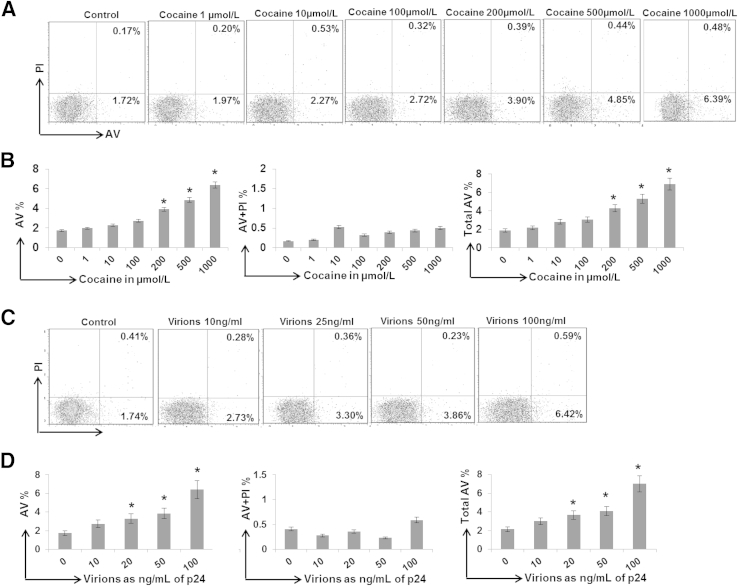

HIV-1 infection causes decline of both infected and uninfected CD4+ T cells. However, decline of uninfected cells plays a critical role in HIV-1–associated immunodeficiency.29–32 Therefore, we examined the effects of cocaine on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis using uninfected resting CD4+ T cells from healthy donors. These cells were treated with 1, 10, 100, 200, 500, and 1000 μmol/L cocaine, respectively, for 24 hours, and apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using AV as the early apoptosis marker and PI as the late apoptosis marker. Data presented in Figure 1, A and B demonstrated that cells treated with cocaine (up to 100 μmol/L) show a minimal increase in AV staining compared with untreated cells. However, cocaine at concentrations of 200 to 1000 μmol/L showed a dose-dependent increase in the AV and total AV (AV+ and AV+/PI+) staining (Figure 1B). This is consistent with cells from six different donors that showed maximum increase in AV and total AV staining with 1000 μmol/L cocaine (Figure 1B). These results suggested that cocaine (up to 100 μmol/L) has a limited apoptotic effect on resting CD4+ T cells. However, >200 μmol/L cocaine induces CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Effect of cocaine and HIV-1 virions on resting CD4+ T-cell apoptosis: Resting CD4+ T cells were isolated from the PBMCs of HIV-1–negative donors, and cells with >95% purity were used in the experiments. The resting CD4+ T cells were treated with increasing concentrations of cocaine for 24 hours and analyzed by flow cytometry for AV and PI staining to measure early and late apoptosis, respectively (A and B). Representative data from one donor showing the percentage of AV+, PI+, and AV+ PI+ cells (A). Data from cells isolated from six different donors showing fold increase in AV+ cells, AV+ PI+ cells, and total AV+ cells (AV and AV + PI) (B). Apoptosis of resting CD4+ T cells by HIV-1 virions. Cells were exposed to increasing amounts of HIV-1 virions (in terms of viral p24 protein equivalent) for 24 hours, followed by flow cytometry analyses for AV and PI staining (C and D). Representative data using cells from one donor showing the percentage of AV+, PI+, and AV+ PI+ cells (C). Data from cells isolated from six donors showing fold increase in AV+, AV+ PI+, and total AV+ cells (AV and AV + PI) (D). Results are expressed as means ± SD for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. ∗P < 0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control cells.

Then, we tested the cytotoxicity of HIV-1 virions toward uninfected resting CD4+ T cells. We used the infectious X4 tropic HIV-1 LAI virions, because X4 virions are associated with rapid CD4 T-cell loss and linked to HIV-1 disease progression.33,34 The CD4+ T cells were exposed to increasing amounts of virions (2, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 ng/mL of viral p24 protein equivalent) for 24 hours and analyzed for the induction of apoptosis by AV and PI staining (Figure 1, C and D). Treatment of cells with virions (up to 50 ng/mL equivalent of p24) showed moderate-level apoptosis, as illustrated by AV+ cells compared with untreated cells. However, cells treated with virions at 100 ng/mL of p24 showed an approximately fivefold increase in AV reactivity (Figure 1C). Predictably, lower amounts of virions (1 to 10 ng/mL of p24) had no effect on AV staining (data not shown). Consistent data were obtained with cells from six different donors that demonstrated maximum apoptosis with virions at 100 ng/mL of p24 (Figure 1D).

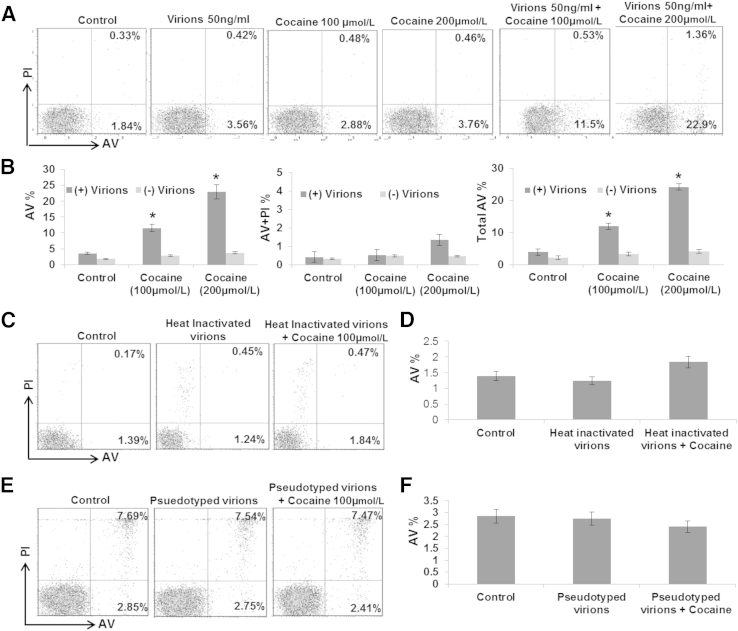

To study the effects of cocaine and HIV-1 together, we used HIV-1 virions at 50 ng/mL of p24 and two concentrations of cocaine (100 and 200 μmol/L). Virion-exposed cells were treated with cocaine, and the total number of AV+ cells was measured by FACS. Interestingly, in the presence of virions, cocaine increased AV staining that is significantly higher compared with AV reactivity induced by cocaine or virion alone (Figure 2, A and B). For example, 2.88% of cells treated with 100 μmol/L cocaine were AV+, whereas, in the presence of virions, AV reactivity was increased to 11.5% (Figure 2A). Furthermore, treatment with 200 μmol/L cocaine increased the AV+ cells to approximately 23%, suggesting that cocaine and HIV-1 likely have a synergistic effect on resting CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. Notably, this synergy was abrogated with heat-inactivated virions, as depicted by the comparable levels in AV staining between cells treated with inactivated virions and cells treated with both cocaine and inactivated virions (Figure 2, C and D). Similarly, use of vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped virions also lacked the synergy between cocaine and HIV-1 virions (Figure 2, E and F), highlighting the important role of HIV-1 envelope protein in resting CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Synergy between cocaine and HIV-1 virions on resting CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. Resting CD4+ T cells were exposed to HIV-1 virions (50 ng/mL of p24 equivalent) and/or cocaine (100 and 200 μmol/L, respectively), followed by flow cytometric analyses for AV and PI staining (A and B). Representative flow cytometry data from one donor showing percentage of AV+, AV+ PI+, and PI+ cells (A). Data using cells from six different donors showing the percentage increase in AV+ cells (B). CD4+ T cells were exposed to heat-inactivated HIV-1 virions (50 ng/mL of p24 equivalent) and/or 100 μmol/L cocaine, followed by flow cytometric analyses for AV and PI staining (C and D). Representative data from one donor showing percentage of AV+, AV+ PI+, and PI+ cells (C). Data using cells from three different donors showing the percentage increase in AV+ cells (D). CD4+ T cells were exposed to VSV-G–pseudotyped HIV-1 virions and/or 100 μmol/L cocaine, followed by flow cytometric analyses for AV and PI staining (E and F). Representative data from one donor showing percentage of AV+, AV+ PI+, and PI+ cells (E). Data using cells from three different donors showing the percentage increase in AV+ cells (F). Results are expressed as means ± SD for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. ∗P < 0.05 for treated cells versus untreated cells.

The Synergistic Effects of Cocaine and HIV-1 on CD4+ T-Cell Apoptosis Are Not Due to Increased Infection or Immune Activation

HIV-1 infection induces immune activation and CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.35 Therefore, we tested whether the observed apoptosis was due to infection. Our results showed that cells exposed to virions (at 50 ng/mL of p24) exhibited no/negligible infection (<2%), as measured by intracellular viral p24 protein by flow cytometry (Supplemental Figure S1). This is not surprising given that HIV-1 infects resting CD4+ T cells at low levels, and detectable levels of p24 are not achieved within 24 hours of infection.36 Notably, cocaine did not increase infection (Supplemental Figure S1), indicating that cocaine’s effect on HIV-associated CD4+ T-cell apoptosis is not likely due to increased infection.

To test whether cocaine increased immune activation of resting CD4+ T cells, we measured the expression of CD69 (early activation marker) and HLA-DR (late activation marker). Our flow analysis showed that cocaine treatment had a minimal effect on the expression of either CD69 or HLA-DR (Supplemental Figure S2A). Similar results were also obtained when cells were stained for the IL-2 receptor, CD25 (Supplemental Figure S2B). HLA-DR expression in cells treated with cocaine from six different donors also showed minimal impact on immune activation (Supplemental Figure S2C). These results suggested that the CD4+ T-cell apoptosis by cocaine may not be due to increased infection or immune activation.

Cocaine Accentuates HIV-1–Induced CD4+ T-Cell Apoptosis by Increasing ROS and Mitochondrial Membrane Depolarization

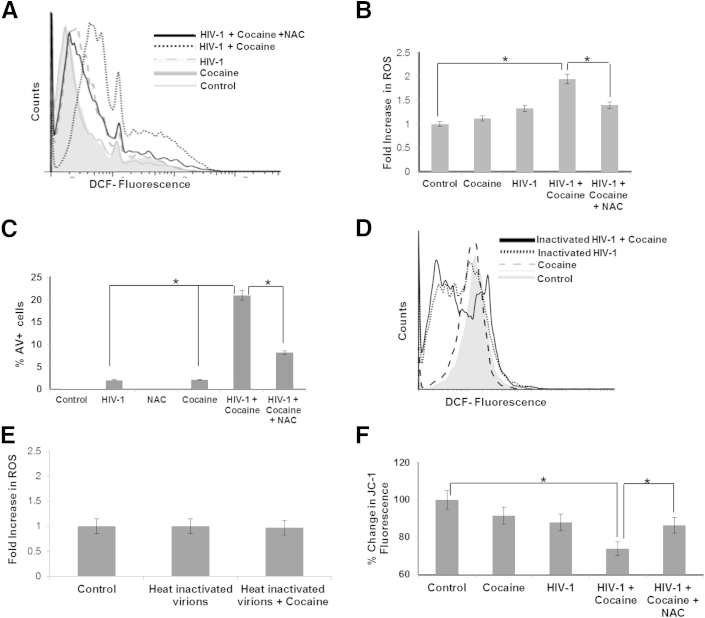

HIV-1–induced CD4+ T-cell apoptosis has been shown to be mediated by mitochondrial oxidative stress, specifically membrane depolarization and ROS.30,37–39 Therefore, we tested whether cocaine enhances HIV-induced ROS generation in resting CD4+ T cells. To test this, virion-treated CD4+ T cells were subjected to the peroxide-sensitive fluorescent probe, DCF, in the presence or absence of cocaine. Our results demonstrated that individual virions (50 ng/mL of p24) or 200 μmol/L cocaine minimally increased intracellular ROS (Figure 3, A and B). However, when cocaine was added to cells treated with virions, there was a significant increase in ROS levels compared with cells treated with virion or cocaine alone (Figure 3, A and B). Furthermore, when cells were pretreated with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), a potent antioxidant before treatment, the effects of cocaine on ROS generation in the HIV-1–treated cells were diminished (Figure 3, A and B). Furthermore, AV staining of NAC-treated cells showed that the antioxidant also reduced the excessive apoptosis induced by cocaine and HIV-1 virions, as seen by the significant decrease in total number of AV+ cells (Figure 3C). Notably, the DCF fluorescence was unchanged when cells were treated with heat-inactivated virions in the presence or absence of cocaine (Figure 3, D and E). Collectively, these data illustrated that increased ROS by cocaine and HIV-1 virions may play a major role in CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Cocaine potentiates HIV-1–induced ROS generation and mitochondrial depolarization of resting CD4+ T cells. Primary uninfected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with either 200 μmol/L cocaine and/or HIV-1 virions (50 ng/mL of p24 equivalent) for 24 hours and assayed for the production of ROS using a DCF-based fluorescence assay and a JC-1–based mitochondrial depolarization assay, as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were treated with 100 μmol/L NAC, concurrent with cocaine and/or HIV-1 virions. Representative spectra of DCF fluorescence in cells from one donor (A). Fold increase in ROS generation, as measured by DCF fluorescence using cells from three different donors (B). Apoptosis was measured as the percentage increase in AV+ cells by flow cytometry using cells from three different donors (C). ROS measurements by DCF fluorescence using heat-inactivated HIV-1 virions in the presence or absence of cocaine (D and E). Representative spectra of DCF fluorescence in cells from one donor (D). Fold increase in ROS generation using cells from three different donors (E). CD4+ T cells were treated with 200 μmol/L cocaine and/or HIV-1 (50 ng/mL of p24) for 24 hours, and mitochondrial membrane potential was measured by staining with JC-1 dye (F). The membrane potential was quantified as a ratio of the aggregate (red fluorescence) to monomer JC-1 (green fluorescence) in the cells from three different donors. Results are expressed as means ± SD for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. ∗P < 0.05 for treated cells versus untreated cells.

Increased ROS is known to cause mitochondrial membrane depolarization and induction of apoptosis.39–41 Therefore, we measured mitochondrial membrane potential in resting CD4+ T cells treated with cocaine and/or virions using the ratio of JC-1 green/red fluorescence that has been demonstrated to be a good indicator of mitochondrial depolarization.42 As shown in Figure 3F, the ratio of JC-1 red/green fluorescence was significantly decreased (approximately 26%) when cells were treated with cocaine and virions compared with cells treated with virions (approximately 12%) or cocaine (approximately 9%) alone. Notably, cells treated with NAC showed restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential. These data strongly suggested that cocaine accentuates HIV-1–induced mitochondrial depolarization in resting CD4+ T cells.

Cocaine Enhances Apoptosis of CD4+ T Cells Isolated from HIV-1–Infected Subjects

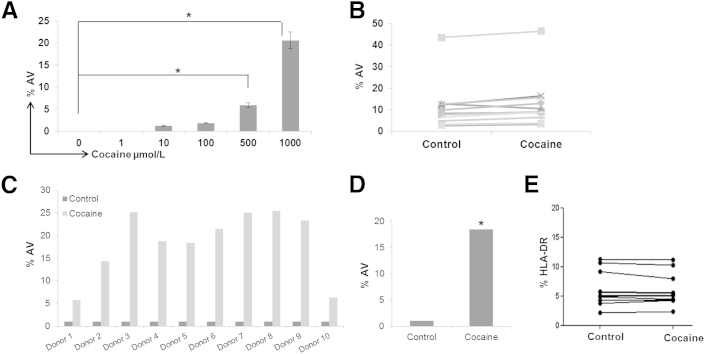

Last, we evaluated whether cocaine can induce apoptosis of resting CD4+ T cells of HIV-1–infected subjects that have never received ART. First, we performed dose-response analysis using PBMCs from four HIV-1–infected individuals. The PBMCs were treated with cocaine at concentrations of 1 to 1000 μmol/L for 24 hours, and apoptosis was measured by AV staining. Similar to the data obtained with cells from HIV-1–negative individuals, cocaine (up to concentrations of 100 μmol/L) had a minimal effect on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. However, a significant increase in apoptosis was observed at 500 to 1000 μmol/L of cocaine, as illustrated by an increased percentage of AV+ cells (Figure 4A). For example, approximately 20% of the cells treated with 1000 μmol/L cocaine stained positive for AV (Figure 4A). We then evaluated 10 additional HIV-1–positive donors using 1000 μmol/L cocaine. Cocaine treatment consistently enhanced AV staining, with an increase in apoptosis from approximately 5% to 25% among donors (Figure 4, B and C) and an average increase of approximately 18.75% in AV+ staining (Figure 4D). This increase is not due to immune activation because cocaine showed a minimal effect on HLA-DR expression (Figure 4E). Collectively, these data support our results from HIV-1–negative individuals for the effects of cocaine on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Cocaine enhances apoptosis of resting CD4+ T cells of HIV-1–infected patients. PBMCs of ART-naïve HIV-1–positive donors were thawed, washed, and cultured overnight. Then, these cells were treated with cocaine in a dose-dependent manner for 24 hours, followed by measurement of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Percentage of AV+ CD4+ T cells from four different donors (A). Effects of 1000 μmol/L cocaine on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis, as determined by AV+ staining using PBMCs of 10 different ART-naïve HIV-1–positive donors (B). Results in A and B are expressed as means ± SD for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. ∗P < 0.05 for treated cells versus untreated cells. Relative percentage change (C) and average increase in CD4+ T-cell apoptosis (D) as a function of cocaine treatment using PBMCs of 10 different ART-naïve HIV-1–positive donors. Effects of cocaine on CD4+ T-cell immune activation, as measured by HLA-DR expression using PBMCs of eight different ART-naïve HIV-1–positive donors (E).

Discussion

Cocaine, a commonly used drug among HIV-1 patients,43 serves as a powerful cofactor for HIV-1 infection, disease progression, and AIDS-related mortality.2–4,6,11,12,17,44–49 Studies suggest that cocaine-abusing HIV patients have lower CD4+ T-cell counts and accelerated decline in CD4+ T-cell number.45–50 There is also evidence that HIV-1–negative cocaine addicts have reduced levels of total CD4+ T cells compared with nonusers.50 Animal studies also demonstrated that cocaine decreases the number of circulating lymphocytes.51,52 However, the underlying mechanism for the effects of cocaine on human CD4+ T-cell decline remains unclear. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of cocaine on the apoptosis of resting CD4+ T cells, because decline of uninfected resting CD4+ T cells is proposed to be the major driver of T-cell depletion in AIDS patients.29–32,35 We treated cells from HIV-1–negative and HIV-1–positive donors with cocaine and found that cocaine at concentrations of 1 to 100 μmol/L had a minimal effect on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. However, cocaine >100 μmol/L induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, with maximum apoptosis induced with 1000 μmol/L (Figures 1 and 4). Notably, cells from HIV-1 patients treated with 1000 μmol/L cocaine showed higher levels of apoptosis (Figure 4A) compared with the cells from healthy donors (Figure 1A). This increased susceptibility may be due to an altered immune system in HIV-1–infected patients, use of frozen cells compared with the fresh cells of healthy donors, or treatment of mixed PBMC cultures in HIV-1–infected patients compared with the pure cultures of CD4+ T cells for healthy donors. In addition, cocaine and other drug use among the donors used cannot be excluded.

We used 1 to 1000 μmol/L cocaine to cover the wide range of plasma concentrations reported in cocaine abusers. For example, Blaho et al25 reported that serum levels in patients admitted to the emergency department averaged approximately 1.0 μmol/L. Mittleman and Wetli26 detected a mean concentration of 21 μmol/L cocaine in an acute fatal overdose. In addition, Karch et al27 found that 3.6 μmol/L is the mean concentration in cocaine-poisoned patients. However, there is also evidence that cocaine concentration can go up to 100 to 1000 μmol/L in the plasma of drug addicts. For example, in the study by Blaho et al,25 a concentration up to 120 μmol/L was observed in a surviving patient. Notably, a study by Peretti et al28 described that the serum concentration exceeded 1000 μmol/L after an acute fatal overdose. Although Mittleman and Wetli26 reported the mean concentration of cocaine at 21 μmol/L, the highest level was reported to be 70 μmol/L. Similarly, in the study by Karch et al,27 the highest detected cocaine concentration was 62 μmol/L. It is also critical to consider that these reported concentrations are most likely not the peak concentrations in the plasma of cocaine addicts. This is for the following reasons: i) the measurements of cocaine concentrations in the plasma are almost always conducted a few hours after cocaine use, ii) cocaine has a short half-life (<60 minutes), and iii) peak cocaine concentrations are achieved within 5 seconds to 60 minutes, depending on mode of administrations.23,24,53–55 However, we acknowledge that concentrations >100 μmol/L may not be prevalent among cocaine abusers, and the physiological relevance of our data is unclear. Nevertheless, examining the effects of cocaine on CD4+ T cells, albeit higher than physiological concentrations, may help us elucidate the molecular interaction between cocaine and CD4+ T cells. These studies will shed critical insights into the cellular signaling pathways and pharmacological and immunomodulatory effects of cocaine on CD4+ T cells.

Although the mechanism by which cocaine reduces T-cell numbers is unclear, the immune modulatory function of cocaine has been suggested to play a role.50 Our data illustrated that cocaine treatment did not significantly increase immune activation of resting CD4+ T cells of HIV-1–negative or HIV-1–positive individuals (Figure 4E and Supplemental Figure S2). Although Ruiz et al50 described increased immune activation among cocaine addicts, their study examined effects of chronic cocaine abuse in contrast to the acute exposure of cocaine used in our experiments. Notably, in a follow-up study, Ruiz et al56 illustrated that acute cocaine exposure did not alter T-cell activation, similar to our findings on the effects of cocaine on CD4+ T-cell immune activation. Carrico et al57 also described that stimulant use (both cocaine and methamphetamine) is associated with higher levels of immune activation among HIV-positive persons taking ART. However, these authors compared immune activation only among HIV-1–positive patients. Given that HIV-1 infection causes immune activation, whether these stimulants had a direct effect on immune activation remained inconclusive. In addition, our data were derived in the cultures of CD4+ T cells treated with only cocaine, whereas Carrico et al57 conducted their studies in humans that abuse both cocaine and methamphetamine.

We also tested the effects of cocaine on HIV-1 infection, because HIV-1 infection is known to induce CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.35 Our data showed that HIV-1–exposed resting CD4+ T cells have a low level of infection and that cocaine did not increase infectivity (Supplemental Figure S1). This is in contrast to a recent report by Kim et al58 that suggested that cocaine enhances HIV-1 infection in quiescent CD4+ T cells. However, these authors used a low concentration of cocaine (10 nmol/L), treated the cells for 3 days with cocaine, and found a significant difference in infection only 3 days after infection. Because our data were generated by exposing cells for 24 hours, infection may not explain the increase in apoptosis.

It is well documented that binding of HIV-1 envelope protein to the CD4+ receptor and C-X-C chemokine 4/CCR5 coreceptors of CD4+ T cells induces apoptosis.59–61 More important, ROS-mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress plays a critical role in HIV-1–induced CD4+ T-cell apoptosis.37–41 Furthermore, cocaine has also been shown to increase ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential in neuronal cells.62,63 Therefore, we tested whether ROS-mediated oxidative stress plays a role in cocaine and HIV-1–induced CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. Data in Figure 3 illustrated that cocaine had a minimal impact on ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential. However, in virion-exposed cells, cocaine significantly increased ROS levels and mitochondrial depolarization. Notably, the synergy between cocaine and HIV-1 was abrogated with heat-inactivated or VSV-G–pseudotyped virions (Figure 2, C–E). Therefore, our data strongly suggest that the synergistic effect of cocaine and HIV-1 on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis is mediated by increased oxidative stress that is mostly likely mediated by the HIV-1 envelope protein.

A direct link between cocaine use and HIV-1 disease progression remains contentious because substance use is often associated with reduced ART/nonadherence to ART. Furthermore, history and route of drug use, amount and formulation of drug used, single or concurrent use of other drugs, and poor nutrition can also influence outcomes of HIV-1 disease. Our ex vivo model alleviates many of these challenges and measures effects of cocaine and HIV-1 on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis. Therefore, we tested the effects of cocaine on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis using PBMCs from 15 ART-naïve patients. We treated the PBMCs of HIV-1–infected patients only with cocaine, assuming that these cells are exposed to HIV-1 because these individuals had a viral load ranging from 20,000 to 100,000 RNA copies/mL. We also postulated that the resting CD4+ T cells are uninfected because a small percentage (0.01%) of resting CD4+ T cells in HIV-1 patients are infected.50 Surprisingly, we did not observe a synergy on CD4+ T-cell apoptosis (Figure 4A). Because increased levels of apoptosis were observed only when cells from healthy donors were treated with virions at 50 ng/mL of p24 (Figure 2), we calculated the amount of circulating virions from RNA copy numbers.64 We found that the viral load of the patients used in this study approximated between 60 and 300 pg/mL of p24 equivalent. Therefore, our data imply that acute cocaine abuse may have limited impact on CD4+ T-cell decline in patients with a viral load <100,000 RNA copies/mL. This is consistent with data reported by Duncan et al,65 which showed that cocaine use was associated with CD4+ T-cell decline in patients with viral loads >100,000 copies/mL. Although Baum et al3 reported that cocaine abuse may accelerate CD4+ T-cell decline in patients with a viral load <100,000 RNA copies/mL, they found that crack-cocaine, not cocaine powder, had an effect on CD4+ T-cell decline. Because we used cocaine powder, it is possible that crack and powder forms of cocaine may have distinct effects on CD4+ T-cell decline. Notably, viral loads >100,000 copies/mL are generally seen among patients with acute infection or high levels of chronic viremia.66,67 Therefore, it is plausible that cocaine abuse may aggravate CD4+ T-cell decline in acutely infected patients or patients with high levels of chronic viremia. In that scenario, the interaction between cocaine abuse and HIV-1 infection may significantly worsen HIV-1 disease progression. However, further research is needed to better understand the molecular interplay between cocaine abuse and HIV-1 disease progression.

Footnotes

This study was partly supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH grants DA024558, DA30896, DA033892, and DIDARP R24DA021471 (C.D.), Research Center for Minority Institution grant G12MD007586, Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant UL1RR024975, and Meharry Translational Research Center CTSA grant (National Center for Research Resources/NIH grant U54 RR026140, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities/NIH U54 grant MD007593, and grant DA029506) that established the patient samples.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental Data

Cocaine and HIV-1–induced apoptosis of uninfected CD4+ T cells is not due to increased infection. Primary uninfected resting CD4+ T cells were exposed to HIV-1 virions (50 ng/mL of p24 equivalent) in the presence and absence of cocaine. After 48 hours, intracellular p24 levels were measured by flow cytometry. Representative data from one donor showing the percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 (A). Percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 using cells from six different donors (B). Results are expressed as means ± SE for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate.

Cocaine and HIV-1–induced apoptosis of uninfected CD4+ T cells is not due to immune activation: Primary uninfected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with and without 200 μmol/L cocaine for 24 hours and analyzed for the expression of immune activation markers CD69, HLA-DR, and CD25 by flow cytometry. Representative data on expression of immune activation markers using cells from one donor (A and B). HLA-DR expression data using cells from six different donors (C). Results are expressed as means ± SE for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

References

- 1.Walensky R.P., Paltiel A.D., Losina E., Mercincavage L.M., Schackman B.R., Sax P.E., Weinstein M.C., Freedberg K.A. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kipp A.M., Desruisseau A.J., Qian H.Z. Non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum M.K., Rafie C., Lai S., Sales S., Page B., Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:93–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cofrancesco J., Jr., Scherzer R., Tien P.C., Gibert C.L., Southwell H., Sidney S., Dobs A., Grunfeld C. Illicit drug use and HIV treatment outcomes in a US cohort. AIDS. 2008;22:357–365. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3cc21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sohler N.L., Wong M.D., Cunningham W.E., Cabral H., Drainoni M.L., Cunningham C.O. Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S68–S76. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vittinghoff E., Hessol N.A., Bacchetti P., Fusaro R.E., Holmberg S.D., Buchbinder S.P. Cofactors for HIV disease progression in a cohort of homosexual and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:308–314. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnsten J.H., Demas P.A., Farzadegan H., Grant R.W., Gourevitch M.N., Chang C.J., Buono D., Eckholdt H., Howard A.A., Schoenbaum E.E. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1417–1423. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnsten J.H., Demas P.A., Grant R.W., Gourevitch M.N., Farzadegan H., Howard A.A., Schoenbaum E.E. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webber M.P., Schoenbaum E.E., Gourevitch M.N., Buono D., Klein R.S. A prospective study of HIV disease progression in female and male drug users. AIDS. 1999;13:257–262. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas G.M., Cheever L.W., Chaisson R.E., Moore R.D. Detrimental effects of continued illicit drug use on the treatment of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:251–259. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas G.M., Griswold M., Gebo K.A., Keruly J., Chaisson R.E., Moore R.D. Illicit drug use and HIV-1 disease progression: a longitudinal study in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:412–420. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas G.M., Gebo K.A., Chaisson R.E., Moore R.D. Longitudinal assessment of the effects of drug and alcohol abuse on HIV-1 treatment outcomes in an urban clinic. AIDS. 2002;16:767–774. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinkin C.H., Barclay T.R., Castellon S.A., Levine A.J., Durvasula R.S., Marion S.D., Myers H.F., Longshore D. Drug use and medication adherence among HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:185–194. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao C., Jacobson L.P., Tashkin D., Martinez-Maza O., Roth M.D., Margolick J.B., Chmiel J.S., Rinaldo C., Zhang Z.F., Detels R. Recreational drug use and T lymphocyte subpopulations in HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pezzotti P., Galai N., Vlahov D., Rezza G., Lyles C.M., Astemborski J. Direct comparison of time to AIDS and infectious disease death between HIV seroconverter injection drug users in Italy and the United States: results from the ALIVE and ISS studies: AIDS Link to Intravenous Experiences: Italian Seroconversion Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:275–282. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199903010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palepu A., Tyndall M., Yip B., O’Shaughnessy M.V., Hogg R.S., Montaner J.S. Impaired virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy associated with ongoing injection drug use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:522–526. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasbach D.A., Desruisseau A.J., Kipp A.M., Stinnette S., Kheshti A., Shepherd B.E., Sterling T.R., Hulgan T., McGowan C.C., Qian H.Z. Active cocaine use is associated with lack of HIV-1 virologic suppression independent of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy: use of a rapid screening tool during routine clinic visits. AIDS Care. 2013;25:109–117. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantri C.K., Pandhare Dash J., Mantri J.V., Dash C.C. Cocaine enhances HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells by down-regulating MiR-125b. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagasra O., Pomerantz R.J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in the presence of cocaine. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1157–1164. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhillon N.K., Williams R., Peng F., Tsai Y.J., Dhillon S., Nicolay B., Gadgil M., Kumar A., Buch S.J. Cocaine-mediated enhancement of virus replication in macrophages: implications for human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:483–495. doi: 10.1080/13550280701528684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth M.D., Whittaker K.M., Choi R., Tashkin D.P., Baldwin G.C. Cocaine and sigma-1 receptors modulate HIV infection, chemokine receptors, and the HPA axis in the huPBL-SCID model. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1198–1203. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manti C.K., Mantri J., Pandhare J., Dash C. Methamphetamine inhibits HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells by modulating anti-HIV-1 miRNA expression. Am J Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.011. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Dyke C., Barash P.G., Jatlow P., Byck R. Cocaine: plasma concentrations after intranasal application in man. Science. 1976;191:859–861. doi: 10.1126/science.56036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heard K., Palmer R., Zahniser N.R. Mechanisms of acute cocaine toxicity. Open Pharmacol J. 2008;2:70–78. doi: 10.2174/1874143600802010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blaho K., Logan B., Winbery S., Park L., Schwilke E. Blood cocaine and metabolite concentrations, clinical findings, and outcome of patients presenting to an ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:593–598. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.9282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittleman R.E., Wetli C.V. Death caused by recreational cocaine use: an update. JAMA. 1984;252:1889–1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karch S.B., Stephens B., Ho C.H. Relating cocaine blood concentrations to toxicity: an autopsy study of 99 cases. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peretti F.J., Isenschmid D.S., Levine B., Caplan Y.H., Smialek J.E. Cocaine fatality: an unexplained blood concentration in a fatal overdose. Forensic Sci Int. 1990;48:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(90)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahr B., Robert-Hebmann V., Devaux C., Biard-Piechaczyk M. Apoptosis of uninfected cells induced by HIV envelope glycoproteins. Retrovirology. 2004;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkel T.H., Tudor-Williams G., Banda N.K., Cotton M.F., Curiel T., Monks C., Baba T.W., Ruprecht R.M., Kupfer A. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat Med. 1995;1:129–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Embretson J., Zupancic M., Ribas J.L., Burke A., Racz P., Tenner-Racz K., Haase A.T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinkelein M., Sopper S., Jassoy C. Contact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected CD4+ T lymphocytes is highly cytolytic for both cells. J Virol. 1995;69:6925–6931. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6925-6931.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connor R.I., Sheridan K.E., Ceradini D., Choe S., Landau N.R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1–infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jekle A., Keppler O.T., De Clercq E., Schols D., Weinstein M., Goldsmith M.A. In vivo evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 toward increased pathogenicity through CXCR4-mediated killing of uninfected CD4 T cells. J Virol. 2003;77:5846–5854. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5846-5854.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lane H.C. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: total CD4+ T-cell pool, immune activation, and inflammation. Top HIV Med. 2010;18:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baldauf H.M., Pan X., Erikson E., Schmidt S., Daddacha W., Burggraf M., Schenkova K., Ambiel I., Wabnitz G., Gramberg T., Panitz S., Flory E., Landau N.R., Sertel S., Rutsch F., Lasitschka F., Kim B., Konig R., Fackler O.T., Keppler O.T. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1682–1687. doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banki K., Hutter E., Gonchoroff N.J., Perl A. Molecular ordering in HIV-induced apoptosis: oxidative stress, activation of caspases, and cell survival are regulated by transaldolase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11944–11953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cossarizza A., Mussini C., Mongiardo N., Borghi V., Sabbatini A., De Rienzo B., Franceschi C. Mitochondria alterations and dramatic tendency to undergo apoptosis in peripheral blood lymphocytes during acute HIV syndrome. AIDS. 1997;11:19–26. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perl A., Banki K. Genetic and metabolic control of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and reactive oxygen intermediate production in HIV disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:551–573. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banki K., Hutter E., Gonchoroff N.J., Perl A. Elevation of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and reactive oxygen intermediate levels are early events and occur independently from activation of caspases in Fas signaling. J Immunol. 1999;162:1466–1479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buttke T.M., Sandstrom P.A. Oxidative stress as a mediator of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1994;15:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandhare J., Cooper S.K., Phang J.M. Proline oxidase, a proapoptotic gene, is induced by troglitazone: evidence for both peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2044–2052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pence B.W., Thielman N.M., Whetten K., Ostermann J., Kumar V., Mugavero M.J. Coping strategies and patterns of alcohol and drug use among HIV-infected patients in the United States Southeast. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:869–877. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook J.A., Burke-Miller J.K., Cohen M.H., Cook R.L., Vlahov D., Wilson T.E., Golub E.T., Schwartz R.M., Howard A.A., Ponath C., Plankey M.W., Levine A., Grey D.D. Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive women. AIDS. 2008;22:1355–1363. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830507f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaisson R.E., Bacchetti P., Osmond D., Brodie B., Sande M.A., Moss A.R. Cocaine use and HIV infection in intravenous drug users in San Francisco. JAMA. 1989;261:561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anthony J.C., Vlahov D., Nelson K.E., Cohn S., Astemborski J., Solomon L. New evidence on intravenous cocaine use and the risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook J.A. Associations between use of crack cocaine and HIV-1 disease progression: research findings and implications for mother-to-infant transmission. Life Sci. 2011;88:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman H., Pross S., Klein T.W. Addictive drugs and their relationship with infectious diseases. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;47:330–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rafie C., Campa A., Smith S., Huffman F., Newman F., Baum M.K. Cocaine reduces thymic endocrine function: another mechanism for accelerated HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:815–822. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruiz P., Cleary T., Nassiri M., Steele B. Human T lymphocyte subpopulation and NK cell alterations in persons exposed to cocaine. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;70:245–250. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pellegrino T., Bayer B.M. In vivo effects of cocaine on immune cell function. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colombo L.L., Lopez M.C., Chen G.J., Watson R.R. Effect of short-term cocaine administration on the immune system of young and old C57BL/6 female mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1999;21:755–769. doi: 10.3109/08923979909007140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans S.M., Cone E.J., Henningfield J.E. Arterial and venous cocaine plasma concentrations in humans: relationship to route of administration, cardiovascular effects and subjective effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1345–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenkins A.J., Keenan R.M., Henningfield J.E., Cone E.J. Correlation between pharmacological effects and plasma cocaine concentrations after smoked administration. J Anal Toxicol. 2002;26:382–392. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.7.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jufer R.A., Walsh S.L., Cone E.J. Cocaine and metabolite concentrations in plasma during repeated oral administration: development of a human laboratory model of chronic cocaine use. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22:435–444. doi: 10.1093/jat/22.6.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruiz P., Berho M., Steele B.W., Hao L. Peripheral human T lymphocyte maintenance of immune functional capacity and phenotypic characteristics following in vivo cocaine exposure. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:271–276. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carrico A.W., Johnson M.O., Morin S.F., Remien R.H., Riley E.D., Hecht F.M., Fuchs D. Stimulant use is associated with immune activation and depleted tryptophan among HIV-positive persons on anti-retroviral therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim S.G., Jung J.B., Dixit D., Rovner R., Jr., Zack J.A., Baldwin G.C., Vatakis D.N. Cocaine exposure enhances permissiveness of quiescent T cells to HIV infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:835–843. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Algeciras-Schimnich A., Vlahakis S.R., Villasis-Keever A., Gomez T., Heppelmann C.J., Bou G., Paya C.V. CCR5 mediates Fas- and caspase-8 dependent apoptosis of both uninfected and HIV infected primary human CD4 T cells. AIDS. 2002;16:1467–1478. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Algeciras A., Dockrell D.H., Lynch D.H., Paya C.V. CD4 regulates susceptibility to Fas ligand- and tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1998;187:711–720. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arthos J., Cicala C., Selig S.M., White A.A., Ravindranath H.M., Van Ryk D., Steenbeke T.D., Machado E., Khazanie P., Hanback M.S., Hanback D.B., Rabin R.L., Fauci A.S. The role of the CD4 receptor versus HIV coreceptors in envelope-mediated apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology. 2002;292:98–106. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao H., Allen J.E., Zhu X., Callen S., Buch S. Cocaine and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 mediate neurotoxicity through overlapping signaling pathways. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:164–175. doi: 10.1080/13550280902755375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dietrich J.B., Mangeol A., Revel M.O., Burgun C., Aunis D., Zwiller J. Acute or repeated cocaine administration generates reactive oxygen species and induces antioxidant enzyme activity in dopaminergic rat brain structures. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barletta J.M., Edelman D.C., Constantine N.T. Lowering the detection limits of HIV-1 viral load using real-time immuno-PCR for HIV-1 p24 antigen. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:20–27. doi: 10.1309/529T-2WDN-EB6X-8VUN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duncan R., Shapshak P., Page J.B., Chiappelli F., McCoy C.B., Messiah S.E. Crack cocaine: effect modifier of RNA viral load and CD4 count in HIV infected African American women. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1488–1495. doi: 10.2741/2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niu M.T., Stein D.S., Schnittman S.M. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: review of pathogenesis and early treatment intervention in humans and animal retrovirus infections. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1490–1501. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.The CDC MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, June 21, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cocaine and HIV-1–induced apoptosis of uninfected CD4+ T cells is not due to increased infection. Primary uninfected resting CD4+ T cells were exposed to HIV-1 virions (50 ng/mL of p24 equivalent) in the presence and absence of cocaine. After 48 hours, intracellular p24 levels were measured by flow cytometry. Representative data from one donor showing the percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 (A). Percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 using cells from six different donors (B). Results are expressed as means ± SE for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate.

Cocaine and HIV-1–induced apoptosis of uninfected CD4+ T cells is not due to immune activation: Primary uninfected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with and without 200 μmol/L cocaine for 24 hours and analyzed for the expression of immune activation markers CD69, HLA-DR, and CD25 by flow cytometry. Representative data on expression of immune activation markers using cells from one donor (A and B). HLA-DR expression data using cells from six different donors (C). Results are expressed as means ± SE for three separate experiments conducted in triplicate. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.