Abstract

Using a sample of 703 African American adolescents from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS) along with census data from the year 2000, we examine the association between neighborhood-level gender equality and violence. We find that boys’ and girls’ violent behavior is unevenly distributed across neighborhood contexts. In particular, gender differences in violent behavior are less pronounced in gender-equalitarian neighborhoods compared to those characterized by gender inequality. We also find that the gender gap narrows in gender-equalitarian neighborhoods because boys’ rates of violence decrease whereas girls’ rates remain relatively low across neighborhoods. This is in stark contrast to the pessimistic predictions of theorists who argue that the narrowing of the gender gap in equalitarian settings is the result of an increase in girls’ violence. In addition, the relationship between neighborhood gender equality and violence is mediated by a specific articulation of masculinity characterized by toughness. Our results provide evidence for the use of gender-specific neighborhood prevention programs.

Keywords: violence gender gap, gender equality, neighborhoods, masculinity, gender role ideology

The gender gap in crime and violence is a fundamental topic in feminist criminology (Daly & Chesney-Lind, 1988). Although researchers have provided evidence that men are more likely than women to report violence, this difference is less pronounced in gender-egalitarian societies (Goodkind, Wallace, Shook, Bachman, & O'Malley, 2009; Lauritsen & Heimer, 2008; Lauritsen, Heimer, & Lynch, 2009; Steffensmeier & Demuth, 2006; Steffensmeier, Schwartz, Zhong, & Ackerman, 2005). For example, cross-national studies have demonstrated that variations in gender equality across countries are associated with gender differences in rates of physical assault, sexual violence, and/or domestic violence (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006; Straus, 1994; Whaley & Messner, 2002). Although such studies suggest that the geographic gender equality can help explain the gender gap in violent behavior, researchers have largely ignored neighborhood contexts as an important source of variation between women and men and their violent behavior (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993; Fagan & Wright, 2012; Zimmerman & Messner, 2010), and no studies to date have investigated the association between gender equality in residential neighborhoods and gender differences in violence. To address this neglected issue, our first research question concerns whether the gender gap narrows in relation to increased gender equality at the neighborhood level.

Although many have argued that the gender gap lessens in gender-egalitarian social settings, the exact mechanism through which this occurs is unclear. Some scholars have explored this question through variations in masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Messerschmidt, 1993; Schrock & Schwalbe, 2009), whereas others have argued that gender differences in violence are associated with gender role ideology (Adler, 1975; Hagan, Gillis, & Simpson, 1985). Building on this literature, we test hypotheses regarding the factors that mediate the association between neighborhood gender equality and gender differences in violence. We focus on the potential mediating effects of two variables: a particular articulation of masculinity characterized by toughness and gender role ideology.

NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT AND THE GENDER GAP IN VIOLENCE

Classical neighborhood scholars have assumed that violence is mainly the result of community factors. According to this assumption, people who live in disadvantaged areas are more likely to engage in violence than those who live in advantaged areas (Shaw & McKay, 1969). An important element to this argument is its gender neutrality. In traditional studies, neighborhood effects have been hypothesized to influence males and females in similar ways.

Several feminist scholars (e.g., Belknap, 2007; Chesney-Lind & Bloom, 1997) have indicated that traditional neighborhood studies largely ignore gender, only use gender as a control variable, or simply divide a model by gender to examine the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and violence. This has been described as the “add women and stir” approach (Chesney-Lind, 1989; Miller & Mullins, 2009). Feminist scholars believe that the conceptualization of gender is embedded in social systems, and girls and boys have unique experiences in their neighborhoods (Cobbina, Miller, & Brunson, 2008; Miller & White, 2006). Consequently, neighborhood characteristics influence how people behave in gendered ways. Building on this argument, some recent studies have focused specifically on the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and the gender gap in violence (Fagan & Wright, 2012; Karriker-Jaffe, Foshee, Ennett, & Suchindran, 2009). For example, Zimmerman and Messner (2010) examined the role of neighborhood characteristics in determining gender differences in violence. They found that the gender gap in violence is less pronounced when girls and boys reside in disadvantaged neighborhoods because rates of exposure to violent peers is high for both sexes in such areas.

Although a growing number of studies have suggested that the role of neighborhood disadvantage is a function of the gender gap, some have indicated that levels of relative inequality within neighborhoods could effectively predict violent and criminal behavior (Hipp, 2007; Shihadeh & Ousey, 1996). Moreover, several empirical studies have provided evidence that societal gender equality is linked to gender variations in violence, sexual violence, gendered homicide, and domestic violence (Martin et al., 2006; Straus, 1994; Whaley & Messer, 2002). Thus, there is growing evidence that gender equality at the neighborhood level could play a central role in understanding gender differences in violent behavior.

Although gender equality likely influences the gender gap in violence, the way in which this occurs is debatable. Several feminist scholars (Adler, 1975; Chesney-Lind, 2002; Hagan et al., 1985; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996) have proposed the gender-convergence hypothesis that posits that the gender gap in violence decreases as a society becomes more gender equalitarian. In support of this view, numerous time-trend studies have shown that the gender gap in violence tends to decline as societies develop greater gender equality (Lauritsen & Heimer, 2008; Lauritsen et al., 2009; Steffensmeier & Demuth, 2006; Steffensmeier et al., 2005). Nevertheless, research has not yet empirically tested the gender convergence hypothesis using residential neighborhood measures of gender equality.

GENDER EQUALITY AND VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

Over the last two decades, two important perspectives have developed to explain the relationship between gender equality and men and women's violence. Researchers using the ameliorative perspective have argued that men living in gender-equalitarian societies display less violent and criminal behavior than those living in gender-inegalitarian societies (Haynie & Armstrong, 2006; Pratt & Godsey, 2003). This is a function of patriarchal belief systems in which masculinity is a product of gender inequality and is associated with male toughness and aggression (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Messerschmidt, 1993; Schrock & Schwalbe, 2009). Because hegemonic masculinity justifies male dominance (Connell, 1995), violence becomes a means for men to perform masculinity and establish identity. In neighborhoods characterized by gender inequality, gendered lines of power are drawn more starkly, highlighting the societal power differences between men and women and encouraging more traditional expressions of masculinity. Traditional masculinity is characterized particularly by toughness because it is through toughness norms and violence that men demonstrate their “realness” (Titterington, 2006). Therefore, in contrast to those in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods, boys in gender-inegalitarian neighborhoods are more likely to employ violent behavior as a means of showing others that they are strong, powerful, and “real” men.

Although this perspective offers insight for understanding one way in which gender equality may impact violence, questions persist. For instance, although gender inequality may alter expressions of masculinity, some studies indicate that men maintain hegemonic masculinity and power through violence even when residing in gender egalitarian societies (DeWees & Parker, 2003; Martin et al., 2006; Whaley & Messner, 2002). However, it is unclear how these processes may operate at more localized levels because no study has been conducted testing the ameliorative perspective using neighborhood level measurements. Thus, how neighborhood-level gender equality affects male violence and, subsequently, the gender gap in violence is unclear.

In contrast to the ameliorative perspective that is primarily concerned with the behavior of men, researchers using the liberation perspective have proposed that national shifts to a more gender-egalitarian gender ideology have fostered an increase in women's violence (Adler, 1975; Hagan et al., 1985; Hunnicutt & Broidy, 2004). This perspective takes a decidedly dark view of women's liberation in modern societies and argues that as women leave traditional roles of caretaking to pursue careers in male-dominated settings, they must develop male traits of aggression and violence to compete with men (Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). According to this viewpoint, gender equality also alters the way in which young girls are raised. Girls living in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods are socialized in a manner similar to boys and are encouraged to adopt similar roles. They receive, for example, greater freedom and more generous curfews than their counterparts living in neighborhoods where more traditional gender norms prevail (Belknap, 2007; Chesney-Lind, 1989; Hagan et al., 1985; Jacob, 2006). Thus, girls raised in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods develop gender ideologies that encourage them to behave in ways that have been traditionally reserved for boys, including violence.

In contrast to this pessimistic interpretation of female liberation, some scholars have argued that women display low levels of violence regardless of the gender norms dominant in their area of residence (Morash & Chesney-Lind, 1991). In support of this view, no evidence has been found suggesting that girls who live in gender-equalitarian social settings adopt more masculine traits than those who do not (Irwin & Chesney-Lind, 2008). Several recent studies have focused on the question of whether the gender gap in crime and violence has changed over time. This research has found that arrest rates have increased over time, whereas self-report data indicates that women's violence has not really changed. This suggests that the evidence for women's increasing violence is artifactual, resulting from recent changes in enforcement policies (Chesney-Lind, 2002). This supports the idea that women engage in low levels of violence even when gender role ideologies become more egalitarian.

THE CURRENT STUDY

Several scholars have conducted trend analyses to determine whether the gender gap in violent behavior has narrowed. They have assumed that over time, there has been a substantial trend toward gender equality in criminal behavior. Studies of this kind are largely based on official statistics and conclude that the gender gap in violence is closing because women's arrest rates have increased. In contrast to this conclusion, there is growing evidence that gender convergence is caused by decreases in men's violence, whereas women's violence has remained relatively stable (e.g., Goodkind et al., 2009; Schwartz, Steffensmeier, & Feldmeyer, 2009; Steffensmeier & Demuth, 2006; Steffensmeier et al., 2005). Lauritsen and colleagues (2009), for instance, found that since the early 1990s, the gender gap in violence has narrowed because men's rates declined whereas women's rates remained unchanged. Pratt and Godsey (2003) found a similar pattern using cross-national data.

Although these studies have used national data to examine gender differences in violence, no studies have examined this issue using neighborhood data. Thus, we know next to nothing about the relationship between neighborhood-level gender equality and the gender gap in violence. In addition, time-trend designs have failed to include potential mediating variables, such as expressions of masculinity and gender role ideology, in examining the mechanisms of the narrowed gender gap. It remains unclear to what extent and through which mechanisms neighborhood-level gender equality accounts for gender differences in violence.

The perspectives reviewed earlier all argue that a wide gender gap in violence exists within gender-inegalitarian societies and that this gap narrows as gender equality increases. Although they agree that gender equality is associated with a reduction in gender differences in violence, they differ regarding the crime changes that account for this pattern. In addition, several studies have provided evidence that gender differences in violence are explained by the different levels of parental monitoring, deviant peers, and low self-control (Kroneman, Loeber, & Hipwell, 2004). For example, LaGrange and Silverman (1999) indicated that girls living in patriarchal societies tend to experience higher levels of parental monitoring, parental control, and emotional support within the family than boys, which in turn result in gender differences in delinquency. To avoid overestimated results, we controlled for related variables in our analyses.

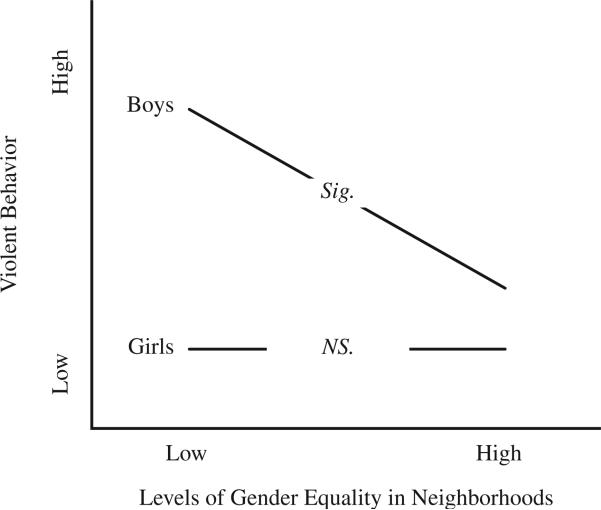

Based on previous studies, we begin by examining the gender convergence hypothesis using neighborhood level data. We expect to find that neighborhood gender equality is associated with a reduction in the gender gap for violence. Having established this association, we go on to investigate whether it is a change in girls’ or boys’ violence that best accounts for this convergence. According to the ameliorative perspective (Haynie & Armstrong, 2006; Pratt & Godsey, 2003), we hypothesize that rates of violence converge for females and males in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods because of a decrease in the violence of males (see Figure 1 depicts this hypothesis). The graph indicates that the gender gap in violence narrows in neighborhoods with high levels of gender equality because boys’ rates of violence decrease whereas the rates for girls remain relatively low regardless of neighborhood gender equality.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model to be tested.

Finally, we examine the extent to which two possible mediators, one informed by the liberation perspective and the other by the ameliorative hypothesis, account for the association between neighborhood gender equality and reductions in the gender gap for violence. First, the liberation perspective argues that increases in women's violence and the resulting gender convergence in violence are a consequence of widespread acceptance of egalitarian gender roles (Adler, 1975; Hagan et al., 1985). Thus, we examine the extent to which traditional gender role ideologies mediate the relationship between neighborhood gender equality and the gender gap in violence. On the other hand, the ameliorative perspective (Haynie & Armstrong, 2006; Pratt & Godsey, 2003) argues that increases in neighborhood gender equality reduces the extent to which men are invested in traditional, aggressive forms of masculinity, characterized primarily by maintaining respect demonstrations of toughness. This change in masculinity expression results in reduced male violence and a convergence in the violent behavior of men and women. We test both possible mediators to better understand the mechanisms through which gender equality encourages the convergence of the gender gap.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Sample

Our study uses Waves 3 and 4 of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS). FACHS was designed to identify neighborhood and family processes that contribute to the development of African American children. The sample strategy was intentionally designed to generate families representing a range of socioeconomic statuses and neighborhood settings. Each family included a child who was in fifth grade at the time of recruitment. At the first wave, the FACHS sample consisted of 889 African American children. At the study's inception in 1997–1998, about half of the sample resided in Georgia and the other half in Iowa; all of the children were in the fifth grade and averaged 10 years of age. Of the 889 respondents at Wave 1, 779 were reinterviewed at Wave 2, 767 at Wave 3, and 714 at Wave 4 (80.31% of the original sample). Details regarding recruitment are described by Simons and colleagues (2012).

The third and fourth waves of data were collected from 2004 to 2005 and from 2007 to 2008 to capture information when respondents were ages 15–16 years and 18–19 years, respectively. At Wave 4, many of the participants no longer resided in Georgia or Iowa. The sample had dispersed across 24 states and 286 census tracts.

Current Study Participants

This study involves both individual and neighborhood characteristics. The measures of neighborhood characteristics were created using the 2000 census Summary Tape File 3A (STF3A), which was geocoded with participants’ residential addresses in 2007. Additional details regarding neighborhood data can be found in Simons, Simons, Burt, Brody, and Cutrona (2005). This study is based on the 703 respondents (305 boys and 398 girls) who provided data on all respondent measurements at the fourth wave. These individuals were nested in 286 census tracts. Comparisons of those participants excluded from this study but retained in the sample did not display any significant differences regarding neighborhood characteristics and violent behavior at Wave 1. Of the 703 respondents, 19% have primary caregivers with less than a high school education, 56% live in a single parent family, and 37% live below the poverty line. Median family income is $27,500. For the 286 census tracts based on the 2000 census, 58% of the neighborhoods are urban areas and 23% have a population more than half of which is African American. The average poverty rate in 2000 is 15% (SD = .11).

Measures

Violent Behavior

At ages 15 (Wave 3) and 18 (Wave 4) years, violent behavior is assessed using respondents’ self-reports on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 4 (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al., 1993). The DISC was developed over a 15-year period of research on thousands of children and parents. Several studies show that the DISC-IV has acceptable levels of test–retest reliability and construct validity (Simons et al., 2012; Stewart & Simons, 2010). The 8-item violence subscale asks respondents to report (1 = yes, 0 = no) whether they have engaged in violent acts such as cruelty to animals, physical assault, threatening others, bullying people, fighting with weapons, robbery, and hurting others. The maximum possible score of 8 corresponds to a subject responding that they had engaged in all of the various acts. Coefficient alphas for the scale are .64 for males and .62 for females.

Toughness

This construct is assessed using a 7-item scale developed by Stewart and Simons (2010) and is meant to measure the extent to which the respondents adhere to toughness as a means of gaining respect. Toughness as measured here is a norm of traditional expressions of masculinity. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) with statements such as people tend to respect a person who is tough and aggressive, people do not respect a person who is afraid to fight for his or her rights, and being viewed as tough and aggressive is important for gaining respect. The coefficient alphas for the scale are .66 for men and .65 for women.

Traditional Gender Role Ideology

Respondents completed the 7-item gender role ideology scale (Kaufman & Taniguchi, 2006). This instrument asks respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) with statements about traditional gender roles (e.g., Women should be concerned with their duties of childrearing and house tending rather than with their careers; and, except in special cases, the wife should do the cooking and house cleaning, and the husband should provide for the family). High scores indicate that respondents are more traditional in their gender role ideology. Coefficient alphas for the scale are .69 for men and .72 for women.

Parental Monitoring

This construct is assessed using three items that asked the respondent to report the extent to which his or her primary caregiver is aware of his or her location, behavior, and school performance. Response format for these items ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Scores were summed to form a measure of parental monitoring. Coefficient alphas for the scale are .69 for men and .72 for women.

Violent Peers

Affiliation with violent peers was measured using a 3-item scale (Stewart & Simons, 2010). Items asked respondents to report how many (1 = none, 3 = all of them) of their close friends had engaged in various violent acts in the past year. Items focused on behaviors such as physical assault, fighting with weapons, and hurting others. All items were summed together. Coefficient alphas for the scale are .76 for men and .66 for women.

Low Self-Control

This construct is assessed using a 17-item scale developed for the current project (Simons, Simons, Chen, Brody, & Lin, 2007) to capture the various elements of low self-control described by Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) in their General Theory of Crime (e.g., impulsivity, insensitivity, physicality, risk-taking, short- sightedness). The response format for all of these items ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 3 (very true) with a coefficient alpha for the scale of .79 for both men and women.

Gender Equality Index

Consistent with prior studies (Martin et al., 2006), gender equality is measured using three socioeconomic items from the 2000 census STF3A: (a) the female-to-male ratio of those 25 years and older with 4 or more years of college education; (b) the female-to-male ratio of those 16 years and older employed in management, professional, and related occupations; and (c) the female-to-male ratio of income levels. We standardized and then summed these items to form an index of neighborhood gender equality. Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the three items load on a single factor with all loadings greater than .5.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

Neighborhood disadvantage is assessed with 2000 STF3A census tract data. Following previous studies (Parker & Reckdenwald, 2008), the scale consisted of four items: Black poverty, Black income inequality, racial segregation, and the percentage of female-headed households. The four items were standardized and summed.

Percentage of Black Residents

African Americans are more likely than other racial groups to reside in extremely disadvantaged and Black-dominated neighborhoods (Peterson & Krivo, 2010). Because we adopt a single ethnic group strategy in this study, neighborhood racial composition may be confounded with our neighborhood measurements. To avoid this bias, we controlled for the percentage of Black residents in the respondent's census tract in 2000 (M = 33.29, SD = 27.85).

Neighborhood-Level Control Variables

We controlled for two variables that might influence associations among the neighborhood variables and violent behavior (Sampson, 2012): residential history and time spent in the neighborhood.

Analytic Strategy

We used multisite samples to examine our models. However, the multisite samples were not independently selected. If samples were directly estimated by a general regression model, nonindependent samples would overestimate the results (B. O. Muthen & Satorra, 1995). To avoid this problem, we used a complex sampling design model available in the Mplus 6.1 statistical software (TYPE = COMPLEX function; L. K. Muthen & Muthen, 2010). This model allowed us to estimate actual standard errors for clustered data in complex mediation or moderation models (MacKinnon, 2007).

Negative binomial regression with a complex sampling design was used in Model 1 because the measure of violence was a count variable, whereas parameters in Models 2 and 3 were examined using an ordinary least squares (OLS) model with a complex sampling design. In all models, we included the main effect with a moderating variable, which was used to test our gender gap hypotheses. The gender equality index was standardized before the interaction terms were calculated. The benefits of using standardized scores in models with interaction terms include reduced multicollinearity and ease of coefficient interpretation. When interaction effects were present, post hoc analyses of significant interaction terms were conducted using the Johnson–Neyman (J–N) technique (Hayes & Matthes, 2009). This procedure identifies regions of significance for interactions between continuous and categorical variables.

The last hypothesis employed mediated-moderation models to examine traditional masculinity expressed through toughness and traditional gender role ideology as possible mediators of the two-way interaction effect of gender and the gender equality index on violent behavior. The logic of the mediated-moderation model is similar to traditional mediated models except that it focuses only on the relationships among an interaction term, mediator, and outcome rather than among other independent variables (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). To assess model fit in the mediated-moderation model, Steiger's root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the chi-square were used. Finally, all direct and indirect effects were examined using Mplus with bootstrap = 1,000 (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006).

RESULTS

Initial Findings

Analysis indicates that 31% of girls and 46% of boys report that they had engaged in at least one type of violent behavior in the past 12 months. Descriptive statistics of the study's variables for both girls and boys are shown in Table 1. On average, boys have significantly higher levels of violence and toughness than do girls. Consistent with previous research, girls report higher levels of parental monitoring (LaGrange & Silverman, 1999), fewer delinquent friends (Esbensen, Deschenes, & Winfree, 1999), a greater likelihood of staying at home than playing outside (Zahn & Browne, 2009), and less traditional gender role ideology (Myers & Booth, 2002). In addition, an unpaired t test shows that there are no significant differences in neighborhood measurements between girls and boys, indicating that in our sample, girls and boys are evenly distributed across neighborhoods.

TABLE 1.

Correlation Matrix and Descriptive Statistics by Gender for the Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Mean | SD | t Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Violent behavior at age 18 years | — | .163** | –.069 | –.193** | .144** | .230** | –.022 | .105* | .047 | –.109* | .084† | 0.528 | 0.962 | 3.16** |

| 2. Respect through toughness | .259** | — | .259** | –.185** | .293** | .253** | .044 | –.012 | .033 | –.043 | .066 | 16.369 | 2.841 | 2.79** |

| 3. Taditional gender ideology | –.092 | .020 | — | –.097† | .209** | .077 | –.045 | –.008 | –.027 | .080 | –.013 | 15.424 | 4.308 | 6.16** |

| 4. Parental monitoring | –.100† | –.045 | –.224** | — | –.107* | –.316** | –.087† | .060 | –.163** | .139** | –.020 | 8.995 | 2.290 | –4.42** |

| 5. Violent peers | .461** | .383** | .035 | –.072 | — | .202** | –.019 | .042 | .038 | –.078 | .045 | 3.440 | 0.849 | 4.66** |

| 6. Low self-control | .238** | .283** | –.041 | –.121* | .223** | — | .060 | .057 | .104* | –.086† | .086† | 25.948 | 4.882 | 0.88 |

| 7. Moved | .001 | –.007 | –.016 | –.030 | .018 | .085 | — | –.163** | .136** | –.112* | –.036 | 0.314 | 0.465 | –2.42* |

| 8. Spending time at current address | –.012 | –.083 | .031 | .027 | –.013 | .090 | –.161** | — | .070 | .043 | –.024 | 4.721 | 1.834 | 3.08** |

| 9. Neighborhood disadvantage | .036 | –.033 | –.028 | –.043 | –.121* | .097† | .229** | –.035 | — | –.350** | –.101* | –0.106 | 2.325 | 1.10 |

| 10. Racial composition | .042 | .112* | –.056 | .161** | –.006 | –.176** | –.123* | .135* | –.331** | — | –.057 | 0.337 | 0.272 | –0.49 |

| 11. Gender equality index | –.131* | –.129* | .105† | .017 | –.063 | .047 | –.021 | –.006 | .073 | –.155** | — | –.045 | 0.972 | 1.36 |

| Mean | 0.787 | 16.983 | 17.379 | 8.215 | 3.807 | 26.297 | 0.233 | 5.105 | 0.104 | 0.327 | 0.059 | |||

| SD | 1.157 | 2.961 | 3.984 | 2.284 | 1.214 | 5.444 | 0.423 | 1.472 | 2.702 | 0.287 | 1.034 | |||

Note. Correlations for girls (n = 398) displayed above the diagonal; correlations for boys (n = 305) displayed below the diagonal. The t value is based on t test for unpaired data at girls versus boys.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .10, two-tailed.

To reduce measurement error, the COMPLEX option in Mplus and robust maximum likelihood estimators were used to correct for clustering bias. Using multivariate regression models, Table 2 displays the results for the model examining whether girls and boys living in neighborhoods with differing levels of gender equality have different levels of violence, toughness, and/or traditional gender role ideologies.

TABLE 2.

Regression Models With Complex Sampling Design Depicting the Results of Main and Moderating Effects Using Violent Behavior, Toughness, and Gender Role Ideology as the Outcomes

| Violent Behaviora |

Toughnessb |

Gender Role Ideologyb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 2c | Model 3a | Model 3b | Model 3c | |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||||||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | .016 (.025) | .021 (.026) | .023 (.027) | .013 (.046) | .021 (.046) | .024 (.040) | –.033 (.075) | –.041 (.075) | –.028 (.082) |

| Percentage of Black Residents | –.205 (.226) | –.233 (.224) | –.043 (.223) | .309 (.400) | .287 (.405) | .791* (.349) | .284 (.588) | .303 (.583) | .714 (.588) |

| Gender Equality Index | –.017 (.062) | .135 (.083) | .090 (.075) | –.060 (.100) | .202† (.105) | .119 (.110) | .163 (.155) | –.063 (.200) | –.073 (.195) |

| Gender Variables | |||||||||

| Male | .298* (.123) | .296* (.121) | .106 (.119) | .621** (.235) | .625** (.225) | .243 (.220) | 1.948** (.336) | 1.944** (.333) | 1.568** (.331) |

| Male × Gender Equality Index | –.321** (.115) | –.292** (.106) | –.564** (.200) | –.408* (.197) | .487 (.351) | .527 (.329) | |||

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||||

| Violent Behavior at Age 16 | .391** (.045) | .380** (.044) | .279** (.044) | .175* (.084) | –.344* (.146) | ||||

| Parental Monitoring | –.061* (.026) | –.069 (.045) | –.296** (.071) | ||||||

| Violent Peers | .217** (.045) | .785** (.108) | .541** (.169) | ||||||

| Low Self-Control | .044** (.010) | .108** (.021) | –.012 (.030) | ||||||

| Moved | –.123 (.131) | –.006 (.201) | –.258 (.370) | ||||||

| Spending Time at Neighborhoods | .068* (.034) | –.076 (.060) | .002 (.095) | ||||||

| Constant | –.906** (.123) | –.892** (.123) | –2.587** (.470) | 16.263** (.206) | 16.283** (.205) | 11.481** (.789) | 15.332** (.296) | 15.315** (.297) | 16.588** (1.282) |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients shown with robust stand errors in parentheses; neighborhood gender inequality is standardized by z-transformation (mean = 0 and SD = 1); N = 703.

Negative binomial regression with complex sampling design.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with complex sampling design.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .10, two-tailed.

Gender Differences in Violent Behavior by Neighborhood Gender Equality

Model 1a consists of gender and neighborhood measurements. The findings reveal that boys are more likely than girls to engage in violent behavior and there are no main effects of the neighborhood measures on violence. Model 1b includes the interaction term between gender and the gender equality index to predict violent behavior while controlling for neighborhood disadvantage and racial composition. As expected, the interaction between gender and the gender equality index is statistically significant. Furthermore, Model 1c shows that the interaction term remains significant (b = –.292, 95% CI [–.500, –.083], p = .006), even after controlling for all neighborhood and individual characteristics.

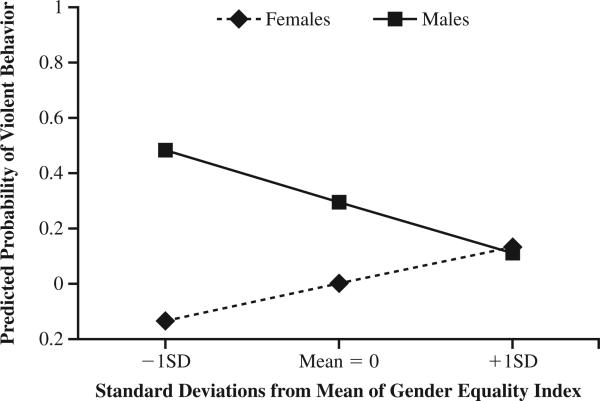

To further examine the interaction between gender and the gender equality index, we graph the effect of gender equality, ranging from –1 to +1 standard deviation from the mean of the gender equality index, on violent behavior (see Figure 2). Using the simple slope procedure (Aiken & West, 1991), the regression line depicting the association between the gender equality index and violence is significantly negative for boys (b = –.112, 95% CI [–.217, –.008], p = .035) but not for girls (b = .055, 95% CI [–.042, .152], p = .265). This result is consistent with our second hypothesis. Given our interest in testing for gender gaps in violence across neighborhood gender equality levels, the J–N technique is used. We find that the difference in violent behavior between girls and boys becomes significant when the gender equality index is less than –.556 standard deviations lower than the mean. In addition, approximately 32.2% of girls and 26.9% of boys in our sample score –.556 standard deviations lower than the mean. Overall, these findings suggest that the effect of neighborhood gender equality on violent behavior is greater for boys than for girls. Boys who reside in neighborhoods with low levels of gender equality are more likely to engage in violence than girls, whereas the gender gap in violence narrows in equalitarian neighborhoods. In particular, the gender-convergence hypothesis is supported by evidence that the gender gap becomes narrower when neighborhood gender equality lessens because boys’ violence scores decrease, whereas girls’ scores remain relatively stable.

Figure 2.

The association between neighborhood gender equality and violent behavior moderated by gender.

Gender Difference in Toughness by Neighborhood Gender Equality

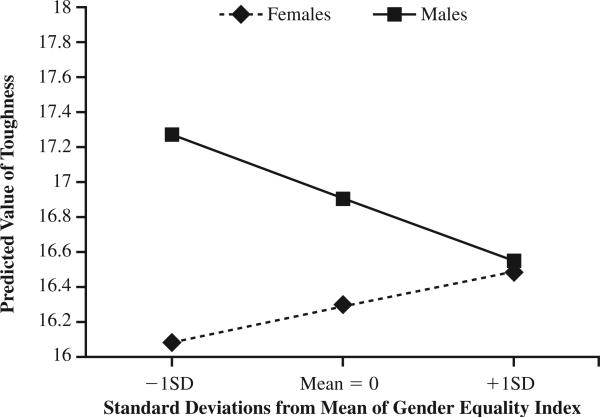

Turning to the measure of toughness, Model 2 in Table 2 shows a pattern of results similar to those obtained for violent behavior. The result shows that there is a significant interaction between gender and the gender equality index in predicting toughness. In addition, Model 2c presents that the result (b = –.408, 95% CI [–.794, –.022], p = .039) holds even after controlling for all neighborhood and individual characteristics.

Similar to our tests for the gender gap in violence, we graph the results of the measure of respect through toughness. Figure 3 indicates a pattern virtually identical to those depicted in Figure 2. An examination of the simple slopes indicates that the slope for the impact of neighborhood gender equality on toughness for boys is significantly different from zero (b = –.289, 95% CI [–.580, –.001], p = .048). In contrast, the slope for girls was not significantly different from zero (b = .119, 95% CI [–.151, .390], p = .387). These findings suggest that neighborhood gender equality is significantly and negatively related to boys’ masculinity expression through toughness. Analysis using the J–N technique indicates that the gender difference in toughness becomes significant when the gender equality index is less than –.569 standard deviations lower than the mean. These results support the hypothesis that the effect of neighborhood gender equality on toughness norms varies by gender. Boys who live in neighborhoods with low levels of gender equality are more likely to express their identity through toughness than those living in equalitarian neighborhoods. Parallel with the violent behavior results, the narrowed gender gap in equalitarian neighborhoods reflects only a decrease in boys’ toughness, not girls’.

Figure 3.

The association between neighborhood gender equality and toughness moderated by gender.

Gender Differences in Traditional Gender Ideology by Neighborhood Gender Equality

Model 3 in Table 2 shows that, controlling for all neighborhood and/or individual characteristics, the interaction between gender and the gender equality index is not significantly associated with traditional gender role ideology. These analyses indicate that there are no gender differences in the effect of neighborhood gender equality on gender role ideology.

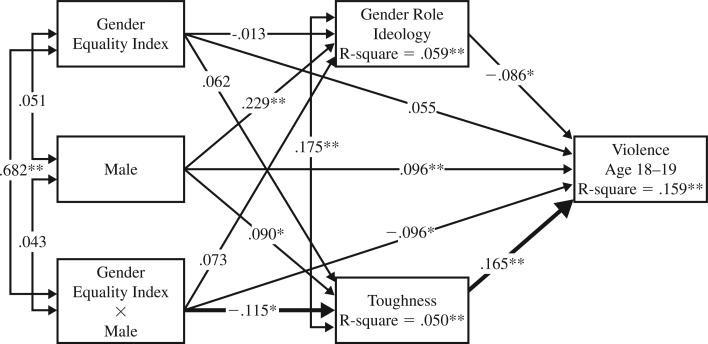

Mediating Effect of Gender Ideology and Toughness

Following the research models discussed previously, we use a mediated-moderation model (Preacher et al., 2006) to determine whether the interaction between gender and gender equality on violent behavior is mediated by toughness or gender role ideology. As shown in Figure 4, the fit indexes show a relatively good fit for the mediated-moderation model (χ2 = 17.504, df = 8, CFI = .953; RMSEA = .041). We find that the interaction between gender and the gender equality index is significantly related to belief in toughness (β = –.115, p = .014), which in turn significantly influences violent behavior (β = .165, p = .000). Based on an indirect effects test (number of bootstrap = 1,000), the results show that there is a significant indirect effect of the two-way interaction term (Gender × Gender Equality Index) on violent behavior through toughness (indirect effect = –.019, 95% CI [–.036, –.002], p = .033). This mediator accounts for about 14% of the interaction effect on violence. Consistent with our hypothesis, the gender gap in violence narrows as neighborhood gender equality increases because boys living in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods are less likely to adopt the masculine toughness norms as an interpersonal strategy for garnering respect and solving problems. Conversely, girls report low levels of belief in toughness across neighborhood contexts.

Figure 4.

Mediated moderation model with gender role ideology and toughness as mediators of the effect of neighborhood gender equality on violence.

Note. χ2 = 17.504, df = 8, p = .025, RMSEA = .041 and CFI = .953. Values are standardized parameter estimate. Using bootstrap methods with 1,000 replications, bold lines indicate that the test of the indirect effect of the interaction term is significant (indirect effect = –.019 [14% portion of the total variance], p = .033). Neighborhood disadvantage and percentage of Black residents are controlled in these analyses. N = 703.

*p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. †p ≤ .10, two-tailed.

DISCUSSION

Across societies, men are more likely than women to engage in violent behavior. However, evidence from studies using time-trend and cross-national analyses have established that gender differences in violence are reduced in gender-egalitarian social settings (Chesney-Lind, 2002; Goodkind et al., 2009; Lauritsen et al., 2009; Pratt & Godsey, 2003; Schwartz et al., 2009; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). Therefore, whether and how the gender gap narrows as a function of gender equality has been understudied. To address this, we extend previous studies by using a neighborhood-level measure of gender equality.

Our results indicate that the effects of neighborhood-level gender equality on violent behavior are moderated by gender. Particularly, gender differences in violence are wide within gender-inegalitarian neighborhoods, whereas these differences decrease within gender-egalitarian neighborhoods. These findings provide evidence for the gender-convergence hypothesis (Chesney-Lind, 2002) and are consistent with the feminist approach indicating that neighborhood contexts are gender-stratified environments (Cobbina et al., 2008).

Based on competing perspectives concerning the influence of gender equality on violent behavior, we identified the hypothesis used to explain the narrowed gender gap in gender-egalitarian settings. The hypothesis assumes that neighborhoods with high levels of gender equality reduce boys’ violence, whereas girls’ violence remains relatively low across neighborhoods. As expected, we find that boys living in gender-inegalitarian neighborhoods have higher levels of violence than those living in gender-egalitarian neighborhoods, whereas girls report lower levels of violence regardless of neighborhood gender equality.

Traditionally, feminists are concerned with whether when, how, and why gender matters (Miller & Christopher, 2006). In this same vein, and using measures of traditional masculinity through adherence to toughness and gender role ideology, we examine the relationships between gender, neighborhood-level gender equality, and violence. We find that boys in gender-inegalitarian neighborhoods are more likely to express their identities through toughness. It is likely that in gender-inegalitarian settings, where stark gender differences are evident, traditional expressions of masculinity are more likely. Young men and boys adopt an expression of masculinity through toughness and violence as a means to handle everyday activities and/or conflicts. However, boys residing in gender-egalitarian settings are less likely to adopt this belief because gender power differences are less pronounced, making traditional expressions of masculinity less salient. Conversely, girls hold a low level of belief in toughness across neighborhoods. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we find that boys’ adherence to the masculine norm of toughness is an important mediator between neighborhood-level gender equality and violence. Neighborhood level gender equality influence boys’ toughness, which in turn affects the likelihood of their violent behavior. This is consistent with the ameliorative perspective. As a result, boys’ violence and aggressive toughness declines and accounts for the narrowing gender gap in violence within gender-egalitarian neighborhoods.

Although our study offers several important findings concerning the gender gap in violence, some limitations must be noted. First, some have argued that people select themselves into neighborhoods. This is a common and problematic confounder of general survey data (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, 2012). Unfortunately, this possible selection bias is nearly impossible to rule out in nonexperimental analysis. In our study, violent behavior at age 15 years has been controlled for in all models to reduce neighborhood selection bias and time effects. Future studies should measure and directly control for this selection-bias effect. Second, gender equality in this study is defined by neighborhood and measured by census data. Some scholars have previously noted the impact of domestic gender equality on individual well-being (Hagan et al., 1985). Future studies should pay more attention to the interaction between neighborhood and domestic gender equality on violent behavior. Third, the sample in this study focuses on African American families living in Iowa and Georgia at the time of recruitment and who were dispersed among 24 states by Wave 4. Although we cannot think of any reasons why the theoretical processes tested in this study should be specific to African Americans, it is clearly the case that our findings need to be replicated using more diverse samples. Fourth, neighborhoods, families, schools, and violence do not exist in a vacuum but are influenced by each other. For example, neighborhood gender equality may relate to individuals who are exposed in domestic violence and school bullying. Future studies should further assess whether neighborhood gender equality can explain gender differences in the forms of violence as well as the relationships among gender equality, domestic violence, school bullying, and youth violence. Finally, our findings imply that gender differences in the relationship between neighborhood structure and violence may be particularly salient in understanding the life experiences of girls as well as boys. However, the study uses only quantitative methods to examine gender gaps that may not fully account for the complexities of gendered life experiences. Future studies should conduct qualitative research that may help to more clearly demonstrate the intersections of gender and neighborhood interactions in everyday life.

Despite these limitations, the current results are noteworthy because they demonstrate that neighborhood measures of gender equality, through toughness, are highly salient factors in determining violence. Based on our findings, girls and boys have different experiences in their neighborhoods because of gender equality levels. Living in more gender-egalitarian neighborhoods is associated with lower odds of violence for both boys and girls, whereas gender differences in violence are more pronounced within gender-inegalitarian neighborhoods. Gender, therefore, is differentially predictive of rates of violence depending on local residence. Indeed, previous researches have supported the argument that gender is more than an individual-level independent variables or a simple control variable (Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). In other words, researchers cannot assume that neighborhood effects will be equal for girls and boys.

Furthermore, social scientists and policymakers have long been concerned about neighborhood effects on individual well-being. Some previous intervention programs have supported the effectiveness of neighborhood intervention in reducing the likelihood of adolescent violence and delinquency (e.g., Institute of Medicine [IOM], 1994). Unfortunately, early intervention programs ignored gender differences in neighborhood context. According to our results, gender-specific neighborhood intervention programs should be developed, and these programs must take into consideration differential effectiveness with different population groups. For example, the neighborhood poverty alleviation policy should consider the fair distribution of economic and social resources by different groups such as gender, race, and different age groups. Another way in which our results can inform public policy is through the creation of youth-based programs that aim to reduce boys’ violent behavior. Our findings suggest that masculine toughness is an influential mediator for boys’ violence in nonegalitarian neighborhoods, and violent intervention programs that promote nonviolent expressions of masculinity and toughness may help impede male physical aggression in these neighborhood contexts. Our study has produced new insights into the role of neighborhoods in the gender gap of violence. Because gender-equalitarian neighborhoods are important for boys as well as for girls, public policy aimed at violence reduction and prevention should include gender-specific practices that are sensitive to the gendered experiences of children and adolescents within any neighborhood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH48165, MH62669), the Center for Disease Control (U01CD001645), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA021898, 1P30DA027827), and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2R01AA012768, 3R01AA012768-09S1). The first author would like to thank Jody Clay-Warner, Thomas McNulty, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Contributor Information

Man-Kit Lei, University of Georgia.

Ronald L. Simons, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University.

Leslie Gordon Simons, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University.

Mary Bond Edmond, Piedmont College, Demorest, Georgia.

REFERENCES

- Adler F. Sisters in crime: The rise of the new female criminal. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J. The invisible woman: Gender, crime, and justice. Wadsworth Publishing; California, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology. 1993;99:353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. Girls’ crime and woman's place: Toward a feminist model of female delinquency. Crime and Delinquency. 1989;35:5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. Criminalizing victimization: The unintended consequences of pro-arrest politics for girls and women. Criminology and Public Policy. 2002;2:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M, Bloom B. Feminist criminology: Thinking about women and crime. In: MacLean B, Milovanovic D, editors. Thinking critically about crime. Collective Press; Vancouver, Canada: 1997. pp. 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbina JE, Miller J, Brunson RK. Gender, neighborhood danger, and risk- avoidance strategies among urban African-American youths. Criminology. 2008;46:673–709. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19:829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Daly K, Chesney-Lind M. Feminism and criminology. Justice Quarterly. 1988;5:497–538. [Google Scholar]

- DeWees MA, Parker KF. The political economy of urban homicide: Assessing the relative impact of gender inequality on sex-specific victimization. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:35–54. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen F, Deschenes E, Winfree LT. Differences between gang girls and gang boys: Results from a multisite survey. Youth and Society. 1999;31:27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Wright EM. The effects of neighborhood context on youth violence and delinquency: Does gender matter? Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2012;10:41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind S, Wallace JM, Shook JJ, Bachman J, O'Malley P. Are girls really becoming more delinquent? Testing the gender convergence hypothesis by race and ethnicity, 1976-2005. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:885–895. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Gillis AR, Simpson J. The class structure of gender and delinquency: Toward a power-control theory of common delinquent behavior. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90:1151–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Armstrong DP. Race and gender-disaggregated homicide offending rates: Differences and similarities by victim-offender relations across cities. Homicide Studies. 2006;16:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp JR. Income inequality, race, and place: Does the distribution of race and class within neighborhoods affect crime rates? Criminology. 2007;45:665–697. [Google Scholar]

- Hunnicutt G, Broidy LM. Liberation and economic marginalization: A reformulation and test of (formerly?) competing models. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2004;41:130–155. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Overcoming Barriers to Immunization . Overcoming barriers to immunization: A workshop summary. Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin K, Chesney-Lind M. Girls’ violence: Beyond dangerous masculinity. Sociology Compass. 2008;2:837–855. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob JC. Male and female youth crime in Canadian communities: Assessing the applicability of social disorganization theory. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice. 2006;48:31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Suchindran C. Sex differences in the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization on rural adolescents’ aggression trajectories. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman G, Taniguchi H. Gender and marital happiness in later life. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;33:735–757. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Is neighborhood context differently related to externalizing problems and delinquency for girls compared with boys? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7(2):109–122. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030288.01347.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGrange TC, Silverman RA. Low self-control and opportunity: Testing the general theory of crime as an explanation for the gender differences in delinquency. Criminology. 1999;37:41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL, Heimer K. The gender gap in violent victimization, 1973-2004. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2008;24:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL, Heimer K, Lynch JP. Trends in the gender gap in violent offending: New evidence from the national crime victimization survey. Criminology. 2009;47:361–399. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, Russell DW. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Martin K, Vieraitis LM, Britto S. Gender equality and women's absolute status: A test of the feminist models of rape. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:321–339. doi: 10.1177/1077801206286311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt J. Masculinities and crime. Rowman and Littlefield; Lanham, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Christopher WM. The status of feminist theories in criminology. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 15. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick, NJ: 2006. pp. 217–249. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Mullins CW. Feminist theories of girls’ delinquency. In: Zahn MA, editor. The delinquent girl. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, White NA. Gender and adolescent relationship violence: A contextual examination. Criminology. 2006;41:1207–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Morash M, Chesney-Lind M. A reformulation and partial test of power control theory of delinquency. Justice Quarterly. 1991;8:347–377. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus 6.0 user's guide. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Myers SM, Booth A. Forerunners of change in nontraditional gender ideology. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parker KF, Reckdenwald A. Concentrated disadvantage, traditional male role models, and African-American juvenile violence. Criminology. 2008;46:711–735. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt TC, Godsey TW. Social support, inequality, and homicide: A cross-national test of and integrated theoretical model. Criminology. 2003;41:611–643. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Great American City. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schrock D, Schwalbe M. Men, masculinity, and manhood acts. Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Steffensmeier DJ, Feldmeyer B. Assessing trends in women's violence via data triangulation: Arrests, convictions, incarcerations, and victim reports. Social Problems. 2009;56:495–525. doi: 10.1525/sp.2009.56.3.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, Cohen P, Placentini J, Davies M, Regier D. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version (DISC-R): I. Preparation, field testing, inter-rater reliability, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:643–650. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, McKay H. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas: A study of rates of delinquency in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh ES, Ousey GC. Metropolitan expansion and black social dislocation: The link between suburbanization and center-city crime. Social Force. 1996;75:649–666. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lei M-K, Stewart EA, Beach SRH, Brody GH, Philibert RA, Gibbons FX. Social adversity, genetic variation, street code, and aggression: A genetically informed model of violent behavior. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2012;10:3–24. doi: 10.1177/1541204011422087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Brody GH, Cutrona C. Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting and delinquency: A longitudinal test of a model integrating community and family level processes. Criminology. 2005;43:989–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Chen Y, Brody GH, Lin K. Identifying the psychological factors that mediate the association between parenting practices and delinquency. Criminology. 2007;45:481–518. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Allan E. Gender and crime: Toward a gendered paradigm of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:459–487. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Demuth S. Does gender modify the effects of race-ethnicity on criminal sanctioning? Sentences for male and female White, Black, and Hispanic defendants. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2006;22:241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Schwartz J, Zhong H, Ackerman J. An assessment of recent trends in girls’ violence using diverse longitudinal sources: Is the gender gap closing? Criminology. 2005;43:355–405. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Simons RL. Race, code of the street, and violent delinquency: A multilevel investigation of neighborhood street culture and individual norms of violence. Criminology. 2010;48:569–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. State-to state differences in social inequality and social bonds in relation to assaults on wives in the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1994;25:7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Titterington VB. A retrospective investigation of gender inequality and female homicide victimization. Sociological Spectrum. 2006;26:205–236. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley RB, Messner SF. Gender equality and gendered homicides. Homicide Studies. 2002;6:188–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn MA, Browne A. Gender differences in neighborhood effects and delinquency. In: Zahn MA, editor. The delinquent girl. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. pp. 164–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman GM, Messner SF. Neighborhood context and the gender gap in adolescent violent crime. American Sociological Review. 2010;75:958–980. doi: 10.1177/0003122410386688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]