Abstract

Racism has historically been a primary source of discrimination against African Americans but there has been little research on the role that skin tone plays in explaining experiences with racism. Similarly, colorism within African American families and the ways in which skin tone influences family processes is an understudied area of research. Utilizing data from a longitudinal sample of African American families (N= 767), we assessed whether skin tone impacted experiences with discrimination or was related to differences in quality of parenting and racial socialization within families. Findings indicated no link between skin tone and racial discrimination, which suggests that lightness or darkness of skin does not either protect African Americans from or exacerbate the experiences of discrimination. On the other hand, families displayed preferential treatment toward offspring based on skin tone and these differences varied by gender of child. Specifically, darker skin sons received higher quality parenting and more racial socialization promoting mistrust compared to their counterparts with lighter skin. Lighter skin daughters received higher quality parenting compared to those with darker skin. In addition, gender of child moderated the association between primary caregiver skin tone and racial socialization promoting mistrust. These results suggest that colorism remains a salient issue within African American families. Implications for future research, prevention and intervention are discussed.

Keywords: skin tone, African Americans, parenting, racial discrimination, racial socialization

Racism and colorism have long been primary sources of discrimination and inequality among people of color, particularly African Americans. Scholars define racism as “the beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation” (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999, p.805), whereas colorism is concerned with skin complexion and ignores racial or ethnic group affiliation. That is, colorism refers to “the allocation of privilege and disadvantage according to the lightness or darkness of one's skin” (Burke, 2008, p.17) and generally privileges lighter skin over darker skin individuals within and across racial and ethnic minority groups (Allen, Telles, & Hunter, 2000; Hunter, 2008; Sahay & Piran, 2997). Decades of empirical research and popular press suggests that both factors represent forms of discrimination that continue to have significant effects on the lives of African Americans (Hall, 2005; Russell, Wilson, & Hall, 1992). However, despite the many studies which have examined both the causes and consequences of discrimination, the issue of skin tone as a cause of racism or as an explanation for differential treatment within African American families has remained an understudied area of research. The goal of the current study is to address this gap in the research.

In recent years, there has been a growing body of literature on racial socialization, which is the process by which explicit and implicit messages are transmitted regarding the significance and meaning of race and ethnicity (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006). Evidence suggest that racial socialization helps foster the adjustment of children in the face of race-related adversity and serves to protect youth from negative mental health consequences (Berkel et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2006). Still, what remains unclear is whether the racial socialization messages transmitted within families vary by skin tone. That is, does skin tone influence the frequency and type of racial socialization message received by adolescents? There is a need to understand the impact of skin tone on family dynamics and race-related outcomes given their unique influence on African American's mental health and long-term functioning. Moreover, if skin tone is found to impact these factors, there are important consequences for adolescents' well-being and, therefore, significant implications for preventative intervention programming for African American families in community and clinical settings.

The present study moves beyond only focusing on race and more closely investigates the complexity of colorism in recognition of the demographic shifts that are changing the nature of the color line in America. Census data projects that by 2050, the majority of Americans will be from minority groups (Bonilla-Silva, 2003) representing an array of skin complexions. Additionally, research shows an increase in interracial couplings and childbearing which also results in large variations in skin complexion (Passel, Wang, & Taylor, 2010; Qian & Lichter, 2011). For these reasons, including measures of skin tone may be vital to the efforts of scholars to advance research on African American families as well as families of color more broadly. We also explore the role of colorism in family dynamics. In particular, we examine the ways in which colorism manifests its effect within families through differences in quality of parenting and racial socialization.

Skin Tone and Racism in the United States

The history of racism in the U.S. has been well documented (McLoyd, 1990). Evidence shows that African American adolescents are particularly at risk for being targets of racial discrimination and that they report experiencing higher levels of racial discrimination than any other racial or ethnic group (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006). In fact, over 90% reported experiencing at least one incident of discrimination during their lifetime and similar results were found using a nationally representative sample of African American adolescents (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Seaton, C aldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008).

While many studies have found a significant association between race, racial discrimination, and various outcomes (Simons, Chen, Stewart, & Brody, 2003; Martin et al., 2010), there is a dearth of research that examines the relationship between skin tone and racial discrimination. Among the few studies that address this issue, findings yield conflicting results. Some research shows that darker skin African Americans report more discrimination (Herring, Keith, & Horton, 2004; Klonoff & Landrine, 2000), while others indicate no significant relationship between these two variables (Keith, Lincoln, Taylor, & Jackson, 2010; Krieger, Sidney, & Coakley, 1998). It is possible that the mixed results from previous studies are due to the use of a dichotomous measure of racial discrimination that focused only on whether African Americans had ever experienced discrimination (e.g. Krieger, Sidney, & Coakley, 1998) or reliance on self-assessments of skin tone (e.g., Klonoff & Landrine, 2000). In an attempt to clarify the mixed findings, we examine whether skin tone is associated with discrimination using a more reliable and comprehensive measure of the type and frequency of racial discrimination as well as observer ratings of skin tone.

Further, most studies have focused on skin tone for individuals who came of age during the Civil Rights Era (Hughes & Hertel, 1990; Keith & Herring, 1991). Although the past body of work has yielded valuable findings, it has failed to examine such effects among a more contemporary sample of African Americans. Thus, it may be that the effects of skin tone seen a few decades ago may not be the same when tested on a younger cohort of African Americans. The current study explores the effects of skin tone on individuals who came of age in the millennium.

Informed by critical race theory, which posits that race and racism are the foundational elements of social structures and systems in American society (Bonilla-Silva, 2003; Delgado, 1995), we investigate the extent to which skin tone is part of discrimination. CRT offers a more broad view of the historical and contemporary issues of racism and has been employed to areas of research such as education (Parker, Deyhle, Villenas, & Crossland, 1998) and sociology (Brown, 2003).

Colorism within African American Families

Parents are the primary agents of socialization during the first several years of life (Simons, Simons, & Wallace, 2004) and, as is the case for all children, family is a particularly salient force in the lives of African American youth (McAdoo, 2002). Parenting exerts strong effects on a variety of outcomes among African American children and adolescents (Brody et al., 2001; Bryant, 2006; Landor et al., 2011; Simons & Conger, 2007). However, it is also the case that a child's characteristics impact the parenting practices of mother and fathers (Belsky, 1984). For instance, a child's weight status, gender, birth order, and other individual traits influence parents behavior toward offspring (Mandara, Varner, & Richman, 2010; McHale, Updegraff, Jackson-Newsom, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000; Simons, et al., 2008). We posit that the same may be true for skin tone.

Research, however, has only recently begun to identify and conceptualize how race and ethnicity operates within the family context through family process measures such as parenting, though even less research has focused on how issues of colorism operate within families (Pinderhughes et al., 2001). Preferential treatment via higher quality of parenting may be one way to conceptualize how colorism operates within the family context. For example, a recent qualitative study on the role of Black families in developing skin tone bias found this bias to be “learned, reinforced, and in some cases contested within families” (Wilder & Cain, 2011, p. 1). Respondents reported their families as the primary influence in shaping how they viewed themselves and others as it related to skin tone. Such transmission of colorism was found to impact how family members treated children of a particular skin tone, with children of lighter skin tone receiving preferential treatment over those with darker skin.

Research conducted in clinical settings has produced mixed findings. For instance, Boyd-Franklin (2003) suggested that parents of dark skin children may “scapegoat” them and hold their lighter skin children in higher regard. In contrast, other parents may provide more support to their darker skin children given that they may view their child's skin tone as a social disadvantage (Greene, 1990). Indeed, there is evidence that darker skin individuals experience more racial discrimination (Klonoff & Landrine, 2000). Thus, parents may attempt to counter racial discrimination or protect their children from it through their approach to parenting. We examine whether offspring's skin tone is related to an increase or decrease in quality of parenting and whether this varies by gender of child.

It is important to note that research in the area of colorism lacks a theoretical framework. As highlighted by race and family scholars in a decade in review article by Burton and colleagues, “this discourse did not lead to formal colorism theories, but it heightened researchers sensitivities to important racial and ethnic subtexts and processes (e.g., intragroup racism) in family life that required the vigilant attention of family researchers” (Burton et al., 2010, p. 443). To this end, goal of the present study is to do just that by using quantitative data to examine the impact of skin tone on family dynamics and race-related outcomes.

Racial Socialization within African American Families

African American families play an important role in teaching their children what it means to be a member of an ethnic minority group. Racial socialization serves as an important protective factor (Granberg, Edmond, Simons, Gibbons, & Lei, 2012; Tatum, 2004). A nationally representative sample found that nearly 64% of African American parents reported transmitting racial socialization messages to their children (Thorton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990). Moreover, nearly 78% of adolescents and 85% of college students reported receiving socialization messages about race (Lesane-Brown, Brown, Caldwell, & Sellers, 2005). Thus, these findings suggest that racial socialization is a common practice in most African American families.

Past studies have investigated several demographic and contextual factors (e.g., gender, age, parent's socioeconomic status, racial identity, and neighborhood) that directly influence racial socialization (Caughy, O'Campo, Randolph, & Nickerson, 2002; Peters & Massey, 1983), but no studies have examined whether racial socialization processes vary by another factor: skin tone. Burton and colleagues lament the “lack of attention to colorism and how it shapes within-race/ethnic socialization practices of families” in their research (Burton et al., 2010, p. 453). We address this issue by examining whether child's skin tone influences the frequency and type of racial socialization messages provided by African American parents.

Previous research on colorism in families has not included a measure of parents' skin tone and has failed to test its potentially moderating effect on the relationship between child's skin tone and family processes such as parenting and racial socialization. Studies have demonstrated that like child characteristics, parent characteristics influence parents' behavior toward offspring (McAdoo, 2002; McLoyd, 1990). Hughes and Chen (1997) found parents' reported discrimination predicted the racial socialization messages they transmitted to their children. It may then also be the case that parents' skin tone impacts their own experiences of discrimination and, therefore, influences their parenting behaviors and racial socialization messages to children. In the current study, we examine whether parent skin tone moderates the relationships between their child's skin tone and both quality of parenting and racial socialization.

The Current Study

The current study addresses many of the limitations of past research on the influence of skin tone on discrimination and family processes. First, while previous studies on colorism utilized samples of baby boomers, we explore the effects of skin tone on a more contemporary sample because the effects of skin tone seen a few decades ago may not be the same when tested on a younger cohort. Second, despite some research suggesting that compared to African American males, African American females are more profoundly affected by skin tone (Allen, Telles, & Hunter, 2000), only a small number of studies examine gender differences when exploring the effects of skin tone. We examine gender as a moderator in this study. Third, most research to date examining skin tone and physical attractiveness has used self-reported measures. We used trained coder's reports of skin tone and physical attractiveness. Fourth, we investigate whether the relationship between adolescent skin tone and both quality of parenting and racial socialization was moderated by parent skin tone. Research has not only failed to include parent skin tone in study measures, but to our knowledge, no study has tested the potential moderating effect of parent skin tone. Fifth, past research on this topic has been cross-sectional, qualitative, or clinical. We use longitudinal, quantitative data to examine the links between colorism and family dynamics. Lastly, prior findings suggest that attractiveness is a cultural construct significantly correlated with skin tone, especially among women (Hill, 2002). Thus, unlike past research, we evaluate the impact of skin tone in models that control for physical attractiveness.

Method

Participants

The current study utilizes data from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a multisite, longitudinal study of over 800 African American families who lived in Georgia and Iowa at recruitment (Simons et al., 2002). FACHS is the largest in-depth panel study of African Americans in the U.S. The first wave of data was collected in 1997 was from 889 target children aged 10 to 12 years old and their primary caregivers. The primary caregiver is defined as the person living in the same household as the child and primarily responsible for his or her care (N= 713 females, 53 males). There were no differences in the sample by geographic location.

Self-report questionnaires were administered in an interview format using a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI). In addition, participants took part in 20-minute videotaped parent-child interaction tasks. Trained coders (3 African American, 3 European American) used these videotapes to rate targets and primary caregivers skin tone and physical attractiveness (Melby, Simons, Connor, & Trumbo, 2011). All coders received approximately 8.0 hours of initial training (personnel procedures, rating manual, rating practice, feedback on ratings, written quiz on rating system, and university assurance training) and practiced as a group of 3–5 people on 9 tapes, and independently rated 12 tapes. Coders began independently scoring after they achieved .8 agreement, or inter-rater reliability on ratings.

The present study utilized two waves of data and consisted of 767 targets (350 males, 417 females) and their primary caregivers. Wave 1 was used to code skin tone. Wave 3 was used to test target reports of racial discrimination, quality of parenting, and racial socialization when targets were approximately 15.5 years of age. This was the first wave at which we had access to all of the other measures used in the present study.

Measures

Skin Tone

Skin tone was coded from videotapes obtained as a part of the FACHS data collection process. Coders rated skin color on a scale from zero to five, with zero indicating a very light skin and five denoting a very dark skin.

Quality of Parenting

This measure was adapted from instruments developed for the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP) and has been shown to have high validity and reliability among African Americans (Simons et al., 2001; Simons, Simons, Burt, Brody, & Cutrona, 2005). Consistent with past research, items assessing the parenting practices of warmth, eschewing hostility, monitoring, consistent discipline, and eschewing harsh discipline were combined to create a 16-item measure. Targets were asked to indicate how often their primary caregiver engaged in activities such as “let you know they care about you; push, grab, hit, or shove you; allow you to do whatever you want after school without knowing what you are doing; discipline you for something at one time and then at other times not discipline you for the same thing.” Responses ranged from 1 (always) to 4 (never). All items were recoded so that higher scores indicated superior parenting and standardized. Cronbach's alpha was .77.

Racial Discrimination

This measure was used to assess targets' perceived racial discrimination and was adapted from the Schedule of Racist Events scale (SRE; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), which has strong psychometric properties and has been used extensively in studies of African Americans of all ages. The current study only included seven items from the SRE scale that pertained to targets and that most likely included treatment from whites, individuals in positions of authority, or an activity that seems unlikely to come from another African American. It assessed the frequency with which various discriminatory events (e.g., hassled by police, yelled a racial slur or racial insult) were experienced during the preceding year. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale 1 (never) to 4 (frequently). Higher scores demonstrated higher racial discrimination. Cronbach's alpha was .84.

Racial Socialization

This accessed how often within the past year have targets received race-related messages. Consistent with Hughes and Johnson (2001), the racial socialization measure was divided into three components. Cultural socialization (3 items, α= .78; e.g., how often… have the adults in your family talked to you about important people/events in the history of your racial group?), Preparation for Bias (4 items, α= .83; e.g., how often… have the adults in your family indicated that people might limit you because of your race?), and Promotion of Mistrust (2 items, α= .65; e.g., how often… have the adults in your family talked about how you can't trust kids from other racial/ethnic groups?). Rating ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (10 or more times).

Physical Attractiveness

This scale was an adaptation of the 5-point Physically Attractive Scale as described in Melby et al. (1998). It assessed the rater's subjective rating of target and primary caregiver's physical features and/or overall physical appearance. It measures the degree to which the respondents may be considered physically unappealing or appealing to the rater. Response categories ranged from 1 (mainly unattractive) to 5 (mainly attractive). The ICC to evaluate interobserver agreement was relatively low at approximately .5.

Family SES

This standardized measure was constructed based on the sum of primary caregiver's highest level of education, measured in years, and household income at Wave 3.

Analytic Techniques

Analysis was conducted using Mplus 5.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2008). Five hierarchical regression models (HRM) were used to examine whether target skin tone predicted quality of parenting, racial discrimination, and the three components of racial socialization. The parameters in the models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. All dependent variables, except quality of parenting, had a strong positive skew. As a result, the variables were transformed using a natural log functions (ln[x+1]) to meet the assumption of linearity for OLS regression (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Furthermore, the independent variables (e.g., target and primary caregiver skin tone) were standardized prior to the calculation of interaction terms. Dawson and Richter (2006) suggest using standardized scores in interaction models to reduce multicollinearity and enable coefficients to be easily interpreted.

The HRMs includes two steps. Step 1 (Model I) includes the control variable— physical attractiveness— and the main effects of target skin tone, primary caregiver skin tone, and target gender. The interaction terms were entered at step 2 (Model II). Step 2 included the interaction of target and primary caregiver skin tone to test for the moderating role of primary caregiver skin tone, the interaction of target skin tone and target gender to test the moderating role of target gender, and the interaction of primary caregiver skin tone and target gender to test the moderating role of target gender. If interactions are significant, post hoc analysis will be conducted using simple slope test (Aiken & West, 1991). It is important to note, however, that the racial discrimination model is the only outcome that does not include a test for the main effect of the primary caregiver and the interactions of primary caregiver skin tone with target skin tone and target gender because there is no theoretical base for testing these relationships. In addition, this study tested the interaction between skin tone and family socioeconomic status to investigate whether family SES moderates study relationships. Past research suggests that the effects of skin tone may operate differently based on SES (Thompson & Keith, 2001)

Results

The distribution of target skin tone by gender shows that the highest proportion of males were classified as medium dark skin (34.5%) and the highest proportion of females were classified as medium skin (31.4%). A chi-square test for independence indicated a significant association between gender and skin tone, χ2 (5 df)= 20.43, p< .001, suggesting a higher proportion of males than females in the darker skin group, which is consistent with biomedical research that has objectively measured skin tone by using tertiles of skin color as measured by reflectometers (Sweet, McDade, Kiefe, & Liu, 2007).

Means, standard deviations, and the correlation matrix are presented in Table 1. Findings show an interesting gender difference in the link between target skin tone and quality of parenting. Target skin tone was positively associated with quality of parenting for males and negatively associated with quality of parenting for females. Furthermore, target skin tone was not related to racial discrimination for males or females. In discussing the three components of racial socialization, for females, target skin tone was not significantly associated with any of the three components of racial socialization but parent skin tone was positively association with promotion of mistrust. Conversely, for males, the positive association between target skin tone and the three components of racial socialization was significant or marginally significant. Target skin tone was only negatively associated with attractiveness among females which is consistent with past research on the link between skin tone, attractiveness, and gender (Hill, 2002) in that lighter skin females are viewed as more attractive. Attractiveness was also associated to quality of parenting for females. Lastly, findings showed an inverse relationship between quality of parenting and racial discrimination for males and females.

Table 1. Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations among Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Target Skin Tone | – | .46** | .12* | .04 | .10† | .11* | .10† | -.04 | .01 | 3.51 | 1.16 | 0- 5 |

| 2. Parent Skin Tone | .48** | – | .03 | -.01 | .10† | .08 | -.02 | -.04 | -.12* | 3.03 | 1.33 | 0- 5 |

| 3. Quality of Parenting | -.09* | -.01 | – | -.22** | .17** | -.02 | -.13* | -.01 | .02 | 54.84 | 5.71 | 0- 64 |

| 4. Racial Discrimination | .03 | -.03 | -.19** | – | .14** | .40** | .08 | .06 | .05 | 1.76 | .65 | 1- 4 |

| 5. Racial Socialization- Cultural Socialization | -.02 | -.01 | .24** | .19** | – | .43** | .11* | -.06 | .07 | 2.48 | .97 | 1- 5 |

| 6. Racial Socialization- Preparation for Bias | .04 | .08 | -.09† | .46** | .36** | – | .30** | .07 | .15** | 2.28 | 1.05 | 1- 5 |

| 7. Racial Socialization- Promotion of Mistrust | .04 | .13* | -.02 | .18** | .15** | .33** | – | .05 | -.08 | 1.35 | .67 | 1- 5 |

| 8. Target Attractiveness | -.15** | .01 | .17** | -.01 | .03 | .03 | -.01 | – | .34** | 3.31 | .83 | 1- 5 |

| 9. PC Attractiveness | -.05 | -.09 | .01 | -.02 | .02 | .03 | -.06 | .36** | – | 2.59 | .96 | 1- 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| M | 3.22 | 2.87 | 54.60 | 1.77 | 2.54 | 2.35 | 1.30 | 3.10 | 2.66 | |||

| SD | 1.10 | 1.35 | 5.88 | .60 | 1.06 | 1.03 | .59 | .94 | 1.06 | |||

Note:

p<.01;

p <.05;

p <.10 (two-tailed tests). Females below diagonal (n=417), males above diagonal (n=350).

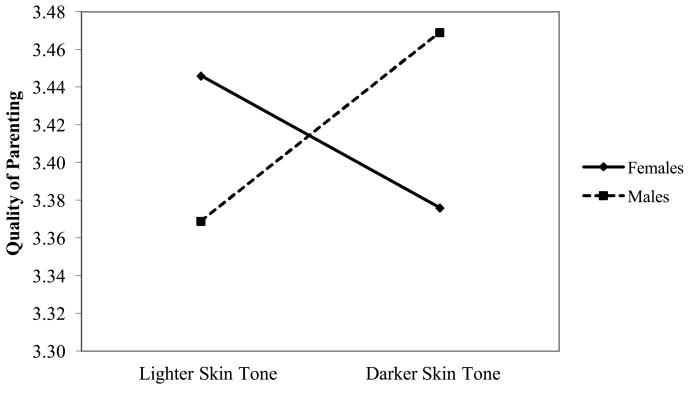

Hierarchical regressions were performed to examine the impact of skin tone on racial discrimination, quality of parenting, and racial socialization, while controlling for target and parent physical attractiveness (see Table 2). Results indicate that target skin tone and target gender are not significant predictors of racial discrimination. The interaction between target skin tone and target gender is also not significant. However, target skin tone is a marginally significant predictor of quality of parenting (β= -.10, p<.10), while accounting for target and parent physical attractiveness. That is, darker skin adolescents tended to receive lower quality of parenting than their lighter skin counterparts. Primary caregiver skin tone and target gender did not predict quality of parenting. The only significant interaction found is between target skin tone and target gender (β= .16, p<.01). Figure 1 illustrates this interaction and indicates that darker skin males receive higher quality of parenting than their lighter skin counterparts, whereas lighter skin females receive higher quality of parenting than their darker skin counterparts.

Table 2. Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Racial Discrimination, Quality of Parenting, and Racial Socialization.

| Racial Discrimination | Quality of Parenting | Racial Socialization | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Cultural Socialization | Preparation for Bias | Promotion of Mistrust | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Intercept | .53** (.02) |

.52** (.02) |

3.414** (.02) |

3.411** (.02) |

.84** (.02) |

.85** (.02) |

.76** (.02) |

.76** (.02) |

.19** (.02) |

.18** (.02) |

| Main Effects | ||||||||||

| Target Skin Tone | .06 (.02) |

.06 (.02) |

-.02† (.02) |

-.10† (.02) |

.03 (.02) |

.02 (.03) |

.06 (.02) |

.03 (.03) |

.09 *(.02) |

.01 (.02) |

| PC Skin Tone | .01 (.02) |

.03 (.02) |

.03 (.02) |

-.02 (.02) |

.06 (.02) |

.08 (.03) |

.01 (.01) |

.11† (.02) |

||

| Target Gender | -.04 (.03) |

-.04 (.03) |

.01 (.03) |

.01 (.03) |

-.02 (.03) |

-.02 (.03) |

-.05 (.03) |

-.05 (.03) |

.05 (.03) |

.05 (.03) |

| Two-way Interaction | ||||||||||

| Target Skin Tone × PC Skin Tone | -.02 (.01) |

-.03 (.01) |

.03 (.02) |

.01 (.01) |

||||||

| Target Skin Tone × Target Gender | .01 (.03) |

.16** (.03) |

.07 (.04) |

.05 (.04) |

.12* (.03) |

|||||

| PC Skin Tone × Target Gender | -.04 (.03) |

.06 (.04) |

-.03 (.04) |

-.14* (.03) |

||||||

| Control Variable | ||||||||||

| Target Attractiveness | .04 (.01) |

.04 (.01) |

0.11** (.01) |

0.11** (.01) |

-.03 (.02) |

-.03 (.02) |

.02 (.02) |

.02 (.02) |

.05 (.01) |

.04 (.01) |

| PC Attractiveness | -.01 (.01) |

-.01 (.01) |

-.03 (.01) |

-.03 (.01) |

.06 (.02) |

.05 (.02) |

.08* (.02) |

.08* (.02) |

-.08* (.01) |

-.08* (.01) |

| Adjusted R2 | .05 | .08 | .12 | .22 | .01 | .02 | .19 | .21 | .17 | .27 |

Note:

p ≤ .01;

p≤ .05;

≤ .10 (two-tailed); All independent variables are standardized by z-transformation (mean= 0 & SD= 1); dependent variables are transformed using the natural logs; n= 767; PC means primary caregiver.

Figure 1.

The relationship between target skin tone and quality of parenting moderated by target gender.

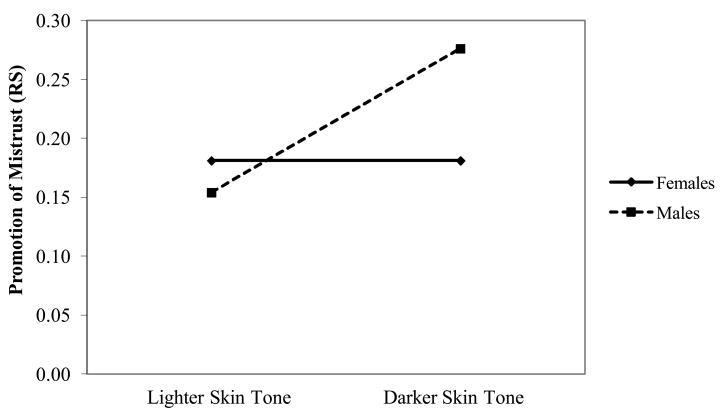

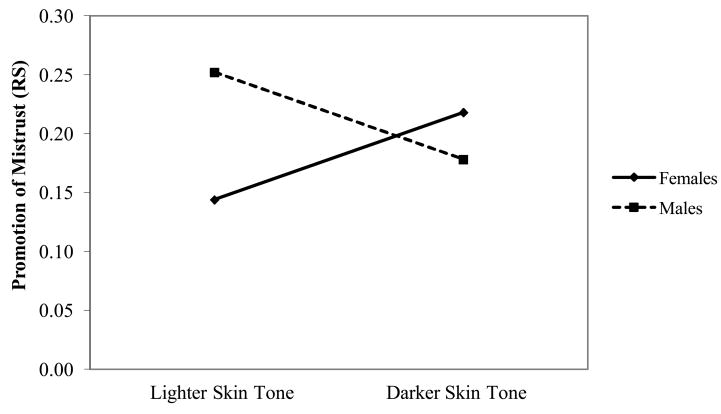

In terms of the three components of racial socialization, the main effects are not significant predictors of cultural socialization and preparation for bias. In addition, there were no significant interactions found among these two components of racial socialization. Target skin tone is a significant predictor of promotion of mistrust (β=. 09, p<.05) prior to adding the interactions in the model. That is, darker skin adolescents tended to received more promotion of mistrust than lighter skin adolescents. The main effects of primary caregiver skin tone and target gender are not significant predictors of promotion of mistrust. Additionally, after adding the interaction terms, primary caregiver skin tone became a marginally significant predictor of promotion of mistrust (β= .11, p<.10) and target skin tone was no longer a significant predictor of promotion of mistrust. There was no significant interaction found between target skin tone and primary caregiver skin tone. However, findings show a significant interaction between target skin tone and gender (β= .12, p<.05). Figure 2 illustrates this interaction and indicates that darker skin males receive more promotion of mistrust messages from their families than their lighter skin counterparts, whereas there was no difference found among darker or lighter skin females. Lastly, there is a significant interaction between primary caregiver skin tone and target gender (β= -.14, p<.05). Figure 3 shows this interaction and indicates that for female adolescents, darker skin parents provide more promotion of mistrust messages than lighter skin parents. Conversely, for male adolescents, lighter skin parents provide more promotion of mistrust messages than darker skin parents. Lastly, this study tested the interaction between skin tone and family SES. All tests were nonsignificant, therefore were omitted from the final models due to space limitation.

Figure 2.

The relationship between target skin tone and racial socialization (promotion of mistrust) moderated by target gender.

Figure 3.

The relationship between primary caregiver skin tone and racial socialization (promotion of mistrust) moderated by target gender.

Discussion

There has been a long history of discourse on the impact of racism and colorism on the experiences of African Americans. Our study addressed understudied areas of research by investigating the impact of skin tone on experiences of racial discrimination and family functioning. Specifically, we were concerned with two issues. First, we examined whether individuals with darker skin experience more racial discrimination. Second, we investigated the extent to which adolescent's skin tone is related to the quality of parenting and racial socialization provided by parents. We addressed these questions using a sample of nearly 800 African American families. Our findings showed no significant relationship between skin tone and racial discrimination for either males or females. This is consistent with results of a recent study (Keith et al, 2010). Because the majority of our respondents do indicate experiencing discrimination, it may be that the lack of relationship between skin tone and discrimination indicates that racial status (e.g., being African American) is a more salient cause of discrimination than skin tone. Therefore, neither lightness nor darkness of skin protects African Americans from or exacerbates the experiences of racial discrimination. This is consistent with the propositions of critical race theory (Bonilla-Silva, 2003; Delgado, 1995), which points to the importance of race in all facets of society. It may also be the case that our measure of discrimination did not capture all of the arenas in which African Americans experience biased treatment. Future research would benefit from consideration of a broader range of discriminatory events.

With regard to colorism in families, results revealed differences by gender of child. In the case of males, darker skin males reported that they received higher quality parenting than did lighter skin males. Several studies have illustrated the effects of skin tone on the outcomes of African American men, where darker skin African American men are at a disadvantage in education, income, and the labor market (Hill, 2000). African American parents are undoubtedly aware of such patterns and may attempt to counter social inequality with additional parental investment in sons with darker skin.

Conversely, for females, lighter skin daughters reported higher quality of parenting. This is consistent with past qualitative research that showed preferential treatment of lighter skin family members (Wilder, 2010). This may be because, for women of color, the notion of beauty is infused not only into a racial paradigm but a skin tone paradigm as well (Celious & Oyserman, 2001; Hunter, 2002: 2007). Society often places high values on beauty in which white beauty is the standard. Thus, beauty— as defined by lighter skin—becomes a form of social capital for African American females. Our findings provide evidence that parents may have internalized this gendered colorism and as a result, either consciously or unconsciously, display higher quality of parenting to their lighter skin daughters and darker skin sons. It is important to note, however, that although our findings are consistent with the explanations offered, future studies would benefit from asking parents about their skin tone preferences directly.

Lastly, this study was concerned with the extent to which skin tone predicts whether adolescents receive racial socialization messages from their parents. Research has shown that African American families play an important role in teaching racial socialization to their children (Lesane-Brown, 2006) and that this process is influenced by child and parent characteristics (Hughes & Chen, 1997), though our study is the first to examine skin tone as one such characteristic. Findings were mixed. Specifically, two aspects of racial socialization, cultural socialization and preparation for bias, were not influenced by target skin tone, primary caregiver skin tone, or target gender. On the other hand, target skin tone did predict promotion of mistrust for males and not females. In other words, male adolescents with darker skin reported receiving more warnings about the potential perils of interactions with other ethnic/racial groups compared to lighter skin males. Given that African American males are more likely to be questioned by police, arrested, incarcerated, and to receive longer sentences, especially those with dark skin (Lundman & Kaufman, 2003; Gyimah-Brempong, Kwabena & Price, 2006), it is likely the case that parents feel it is important to warn their sons to be wary of others. Further, gender of child moderated the association between primary caregiver skin tone and promotion of mistrust. That is, darker skin tone among primary caregivers was associated with more promotion of mistrust for daughters while lighter skin tone among primary caregivers was associated with more promotion of mistrust for sons. Further investigation of this issue is needed in order to understand the significance of these findings.

In summary, our findings are consistent with those from past qualitative studies that indicate colorism remains a salient issue and that skin tone is an additional status marker that exposes African Americans to differing degrees of beneficial family processes. Taken together, these findings seem to highlight a race paradox operating within African American families. It seems that while families transmit racial socialization messages to their children in order to protect them from the realities of racism, some of these families may also, in some cases, perpetuate colorism.

Although the current study has several strengths, it is not without limitations. First, this study included only African Americans. It is important to note that recent studies have identified the existence of colorism among other people of color (Hall, 2008), therefore, future research should replicate these findings using other racial/ethnic groups. Second, we were not able to examine experiences of racism and colorism during early childhood because those measures were not available. Future research would benefit from assessing the experiences of younger children. Third, while we controlled for physical attractiveness, we recognize that such ratings may not be stable from ages 10-12 to ages 13-15. However, while it is possible that adolescents might move up or down a point or two on the rating scale, it is highly unlikely that adolescents move from highly attractive to highly unattractive or vice versa. Further, physical attractiveness was largely a function of the rater's own subjective opinion of attractiveness, influenced by general cultural norms for physical appeal, which resulted in a relatively low interclass correlation of observer ratings on this measure. A final limitation was the small number of fathers in the sample, which prevented us from being able to examine potential differences in family processes between mothers and fathers and whether any such differences varied by gender of offspring. Future studies on the impact of skin tone in families would benefit from a more nuanced examination of the role of gender.

Despite these limitations, the current study had a number of strengths. Whereas past research on skin tone has often employed a qualitative approach or clinical samples, we used a quantitative approach to examine these issues quantitatively among respondents from a community sample. Unlike past research on colorism among baby boomers, our sample was made up of contemporary adolescents. Further, we examined gender differences in the effects of skin tone on racism and family processes. Next, rather than rely on self-assessments of skin tone and physical attractiveness these constructs were coded by trained observers, which allowed for more objective assessments. We also included parent skin tone as a moderator of the relationship between adolescent skin tone and both quality of parenting and racial socialization. To our knowledge, ours was the first study to do so. Finally, because prior research findings suggest that attractiveness is a cultural construct significantly correlated with skin tone, we controlled for physical attractiveness in our models.

Our findings highlight the importance for researchers to recognize that the daily experience of being African American is not homogenous but rather race often interacts with skin tone, gender, and other factors to provide different experiences for African Americans. Homogeneous depictions often eliminate such skin tone and gender distinctions revealed in the current study. Thus, failure to include these differences may result in research inconsistent with social reality of African Americans. Future research should also address whether the relationships between skin tone, colorism, and racism are mediated by other factors.

It is also of value to acknowledge colorism within families because parents can play a role in the solution to eliminating such bias. For example, parent education programs can incorporate discussions about the origins of skin tone bias in the African American community and information about the extent to which skin tone is tied to experiences of discrimination. Highlighting the unintended negative consequences of skin tone bias can begin to reverse any such norms entrenched within African American families and communities. Findings from this study add to the body of knowledge on factors associated with racial discrimination and family functioning and demonstrate the importance of including skin tone as a study variable. Further, the findings can be of use to therapists, educators, and other practitioners to improve their understanding of the complex dynamics that take place among African Americans and within African American families.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH48165, MH62669), the Center for Disease Control (029136-02), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA021898, DA018871).

Contributor Information

Antoinette M. Landor, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 100 East Franklin Street Suite 200, Campus Box 8115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-8115, cell 337.802.2296, fax 919.966.4520, landor@live.unc.edu

Leslie Gordon Simons, Professor, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University, Leslie.Gordon.Simons@asu.edu.

Ronald L. Simons, Foundation Professor, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University and Fellow, Institute for Behavioral Research, University of Georgia rsimons@uga.edu

Gene H. Brody, Regent's Professor, Human Development and Family Science and Director, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia, gbrody@uga.edu

Chalandra M. Bryant, Professor, Department of Human Development and Family Science, University of Georgia, cmb84@uga.edu

Frederick X. Gibbons, Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut, rick.gibbons@uconn.edu

Ellen M. Granberg, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Clemson University, granber@clemson.edu

Janet N. Melby, Adjunct Associate Professor, Human Development and Family Studies and Manager, Behavioral Coding Unit, Survey and Behavioral Research Services, Iowa State University, jmelby@iastate.edu

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen W, Telles E, Hunter M. Skin color, income, and education: A comparison of African Americans and Mexican Americans. National Journal of Sociology. 2000;12:129–180. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Murry VM, Hurt TR, Chen YF, Brody GH, Simons RL, Cutrona C, Gibbon FX. It takes a village: Protecting rural African American Youth in the context of racism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American experience. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children's affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. Critical race theory speaks to the sociology of mental health: Mental health problems produced by racial stratification. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:292–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C. Early experiences and later relationship functioning. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M. Colorism. In: Darity W, editor. International encyclopedia of the social sciences. Vol. 2. Detroit MI: Thomson Gale; 2008. pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Bonilla-Silva E, Ray V, Buckelew R, Freeman EH. Critical race theories, colorism, and the decade's research on families of color. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:440–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00712.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O'Campo PJ, Randolph SM, Nickerson K. The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child Development. 2002;73:1611–1625. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celious A, Oyserman D. Race from the inside: An emerging heterogeneous race model. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:149–165. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A Biopsychosocial Model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JF, Richter AW. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(4):917–926. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R. Critical race theory: the cutting edge. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A Panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(4):517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg EM, Edmond MB, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Lei M. The association between racial socialization and depression: Testing direct and buffering associations in a longitudinal cohort of African Americans young adults. Society and Mental Health. 2012;2(3):207–225. doi: 10.1177/2156869312451152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene B. Sturdy bridges: The role of African American mothers in the socialization of African American children. Women and Therapy. 1990;10:205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah-Brempong Kwabena, Price G. Crime and punishment: And Skin Hue Too? American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings. 2006;96(2):246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hall RE. From the psychology of race to the issue of skin color for people of African descent. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2005;35(9):1958–1967. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02204.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RE, editor. Racism in the 21st century: An empirical analysis of skin color. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Herring C, Keith VM, Horton HD. Skin deep: How race and complexion matter in the “color-blind” era. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hill ME. Color differences in the socioeconomic status of African American men; Results of a longitudinal study. Social Forces. 2000;78:1437–1460. doi: 10.1093/sf/78.4.1437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill ME. Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. The nature of parents' race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In: Balter L, Tamis-Lemonda CS, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; 1997. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children's experiences of parents' racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:981–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic and racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Hertel BR. The significance of color remains: A study of life chances, mate selection, and ethnic consciousness among Black Americans. Social Forces. 1990;68(4):1105–1120. doi: 10.1093/sf/68.4.1105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass. 2007;1:237–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00006.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. If you're light, you're alright: Light skin color as social capital for women of color. Gender & Society. 2002;16:175–193. doi: 10.1177/08912430222104895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keith VM, Herring C. Skin tone and stratification in the Black community. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):760–778. [Google Scholar]

- Keith VM, Lincoln K, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Discriminatory experiences and depressive symptoms among African American women: Do skin tone and mastery matter? Sex Role. 2010;62:48–59. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E, Landrine H. Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;23:329–338. doi: 10.1023/a:1005580300128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S, Coakley E. Racial discrimination and skin color in the CARDIA Study: Implications for public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1308–1313. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Gibbons FX. The role of religiosity in the relationship between parents, peers, and adolescent risky sexual behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:296–309. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9598-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The Schedule of Racist Events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. doi: 10.1177/00957984960222002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL. A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review. 2006;26:400–426. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001. [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL, Brown TN, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM. Comprehensive race socialization inventory (CRSI) Journal of Black Studies. 2005;36:163–190. doi: 10.1177/0021934704273457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundman RJ, Kaufman RL. Driving while black: Effects of race, ethnicity and gender on citizen self-reports of traffic stops and police actions. Criminology. 2003;41:195–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00986.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J, Varner F, Richman S. Do African American mothers really “love” their sons and “raise” their daughters? Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:41–50. doi: 10.1037/a0018072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MK, McCarthy B, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Simons RL, Cutrona CE, Brody GH. The enduring significance of racism: Discrimination and delinquency among black American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;21(3):662–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. The village talks: Racial socialization of our children. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage: 2002. pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Jackson-Newsom J, Tucker CJ, Crouter AC. When does parents' differential treatment have negative implications for siblings? Social Development. 2000;9:149–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Minority children: Introduction to the Special Issue. Child Development. 1990;61:263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02777.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, Rogers S, Rogers B, Scaramella L. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Edition 5) Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; Ames: 1998. p. 18. Unpublished coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Simons LG, Connor AG, Trumbo DL. Skin Tone Rating Manual. Survey and Behavioral Research Services, Iowa State University; Ames: 2011. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen and Muthen; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parker L, Deyhle D, Villenas S, Crossland K. Guest Editors' Introduction: Critical race theory and qualitative studies in education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 1998;11:1–184. doi: 10.1080/095183998236854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Wang W, Taylor P. Marrying Out. Pew Research Center A Social and Demographic Trends Report. 2010 Jun 15; http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/755-marrying-out.pdf.

- Peters MF, Massey GC. Mundane extreme environmental stress in family stress theories: The case of Black families in White America. Marriage and Family Review. 1983;6:193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z, Lichter DT. Changing patterns of interracial marriage in a multiracial society. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:1065–1084. 10.1111/j.1741- 3737.2011.00866.x. [Google Scholar]

- Russell K, Wilson ML, Hall RE. The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color Among African Americans. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay S, Piran N. Skin color preferences and body satisfaction among South-Asian Canadian and European-Canadian female university students. Journal of Social Psychology. 1997;137:167–171. doi: 10.1080/00224549709595427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Conger RD. Linking mother-father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:212–41. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06294593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Granberg E, Chen Y, Simons RL, Conger RD, Brody GH, Murry VM. Differences between European Americans and African Americans in the association between child obesity and disrupted parenting. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2008;39:589–610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chao W, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood deviance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:63–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00063.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chen Y, Stewart EA, Brody GH. Incidents of discrimination and risk for delinquency: A longitudinal test of strain theory with an African American sample. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20(4):827–854. doi: 10.1080/07418820300095711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lin K, Gordon LC, Brody GH, Murry V, Conger RD. Community differences in the association between parenting practices and child conduct problems. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:331–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00331.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Brody GH, Cutrona C. Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting, and delinquency: A longitudinal test of a model integrating community and family level processes. Criminology. 2005;43:989–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2005.00031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Wallace LE. Families, delinquency, and crime: Linking society's most basic institution to antisocial behavior. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet E, McDade TW, Kiefe CI, Liu K. Relationships between skin color, income, and blood pressure among African Americans in the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2253–2259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. Family life and school experience: Factors in the racial identity development of Black youth in White communities. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60:117–135. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00102.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MS, Keith VM. The blacker the berry: Gender, skin tone, self-esteem and self-efficacy. Gender & Society. 2001;5:336–357. doi: 10.1177/089124301015003002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Allen WR. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization of Black parents. Child Development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder J. Revisiting “color names and color notions”: A contemporary examination of the language and attitudes of skin color among youth Black women. Journal of Black Studies. 2010;41:184–206. doi: 10.1177/0021934709337986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder J, Cain C. Teaching and learning color consciousness in Black families: Exploring family processes and women's experiences with colorism. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32(5):577–604. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9706-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]