Abstract

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) have an unparalleled potential for tissue engineering applications including regenerative therapies and in vitro cell-based models for studying normal and diseased tissue morphogenesis, or drug and toxicological screens. While numerous hPSC differentiation methods have been developed to generate various somatic cell types, the potential of hPSC-based technologies is hinged on the ability to translate these established lab-scale differentiation systems to large-scale processes to meet the industrial and clinical demands for these somatic cell types. Here, we demonstrate a strategy for investigating the efficiency and scalability of hPSC differentiation platforms. Using two previously reported epithelial differentiation systems as models, we fit an ODE-based kinetic model to data representing dynamics of various cell subpopulations present in our culture. This fit was performed by estimating rate constants of each cell subpopulation’s cell fate decisions (self-renewal, differentiation, death). Sensitivity analyses on predicted rate constants indicated which cell fate decisions had the greatest impact on overall epithelial cell yield in each differentiation process. In addition, we found that the final cell yield was limited by the self-renewal rate of either the progenitor state or the final differentiated state, depending on the differentiation protocol. Also, the relative impact of these cell fate decision rates was highly dependent on the maximum capacity of the cell culture system. Overall, we outline a novel approach for quantitative analysis of established laboratory-scale hPSC differentiation systems and this approach may ease development to produce large quantities of cells for tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Pluripotent stem cell, differentiation, model, parameter estimation, cell fate self-renewal, expansion, scale-up

Introduction

Both human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have properties of indefinite self-renewal and the capability to generate all somatic cell types (Takahashi et al. 2007; Thomson et al. 1998; Yu et al. 2007). It is because of these characteristics that all human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) possess a tremendous potential for tissue engineering applications including regenerative medicine, in vitro model systems to study development and disease, and pharmaceutical and toxicological screening. Researchers have designed innovative culture and reprogramming systems for generating different somatic cell populations from hPSCs. However, translating these laboratory-scale hPSC differentiation protocols to large-scale bioreactor production processes for producing high purity and high yield populations of somatic cells is one of the current bottlenecks in satisfying demand for therapeutically relevant cell types and ultimately realizing the potential of hPSC-based technology (Azarin and Palecek 2010; Serra et al. 2012). The scale-up of current hPSC differentiation systems will necessitate a thorough understanding of what mechanisms govern dynamics of a differentiating cell population. In addition, design of new large-scale bioprocesses will require quantitative approaches that can ideally be applied to any established laboratory-scale hPSC differentiation system to model and predict strategies to optimize the expansion and differentiation of various cell subpopulations present in culture.

Current laboratory-scale hPSC differentiation systems are designed to guide populations of undifferentiated hPSCs toward a particular cell lineage using microenvironmental cues. Such cues, in the form of soluble factors, extracellular matrix, mechanical forces, cell-cell contact, or various combinations of these, must be introduced in a spatiotemporal-specific manner (Dellatore et al. 2008; Discher et al. 2009; Hazeltine et al. 2013; Metallo et al. 2008a; Serra et al. 2012). Several groups have developed sub-cellular, cellular, or population models to predict cell fate decisions as functions of these cues in various cellular systems, including hPSCs, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), or mouse pluripotent stem cells (mPSC). (Glauche et al. 2007; Prudhomme et al. 2004; Task et al. 2012; Ungrin et al. 2012; Viswanathan et al. 2005; Zandstra et al. 2000). For example, Viswanathan et al. established a computational model to predict mPSC population behavior in response to exogenous stimuli while taking into account endogenous cellular signals at a sub-cellular level (Viswanathan et al. 2005). Glauche et al. developed a model of HSC lineage specification by integrating intracellular dynamics, in terms of estimating propensity for lineage specification, as well as cell population dynamics, which are influenced by microenvironmental signals that may direct differentiation (Glauche et al. 2007). In both of these cases as well as other studies focused on modeling stem cell behavior, it was important to recognize that the total cell population is a dynamic heterogeneous composition of various cell subpopulations, including undifferentiated and differentiated cells, each of which exhibit distinct rates of self-renewal, differentiation, and death that are dictated by the cellular microenvironment (Cabrita et al. 2003; Kirouac and Zandstra 2006; Prudhomme et al. 2004).

A study by Prudhomme et al. investigated individual contributions of different microenvironmental cues on mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) differentiation (Prudhomme et al. 2004). By acquiring data on the kinetics of the transition between undifferentiated and differentiated cells, represented by Oct4+ and Oct4− cells respectively, a cell population dynamics model was fit to these data to decouple kinetic rates of self-renewal and differentiation responses of each subpopulation (Prudhomme et al. 2004). Using this approach, it was possible to estimate cell fate parameters of the specific cell subpopulations present in culture without requiring understanding of underlying intracellular mechanisms.

Here, we outline an approach to quantitatively investigate the efficiency and scalability of distinct hPSC differentiation protocols. By using two robust hPSC epithelial differentiation methods as examples (Lian et al. 2013; Metallo et al. 2010), we first collected cell subpopulation dynamics data and subsequently fit a mathematical model to these data using parameter estimation to calculate various rate constants representing cell fate decisions (self-renewal, differentiation, and apoptosis) for each individual cell type. In performing these analyses, we were able to answer three key questions: 1) Which cell-fate decisions are most limiting in terms of efficiency of the differentiation process? 2) What is the most advantageous stable cell state (i.e. hPSC, progenitor, differentiated cell) at which to target expansion to improve yield or purity of the desired cell type? 3) Given multiple differentiation methods to achieve the same cell type, which method is more favorable for scalable production?

Materials and Methods

Methods are included in Online Supplementary Information.

Results

Compartmentalization of hPSC Differentiation Systems

To investigate efficiency and scalability of hPSC differentiation, we selected epithelial commitment as a model system. Epithelial differentiation, like differentiation of many cell types, involves stable cell states, including a progenitor state and a final differentiated state, that are identifiable by expression of specific marker proteins. Numerous hPSC differentiation protocols exist to generate epithelial cells that express cytokeratin 18 (K18) by using retinoic acid (RA), bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), or ascorbic acid to induce differentiation (Aberdam et al. 2008; Hewitt et al. 2009; Metallo et al. 2008b). Such cells can further differentiate to yield specific epithelial cell types, including keratinocyte progenitor cells, which express cytokeratin 14 (K14), coupled with a loss of K18, when cultured under specific conditions (Aberdam et al. 2008; Itoh et al. 2011; Metallo et al. 2010; Metallo et al. 2008b).

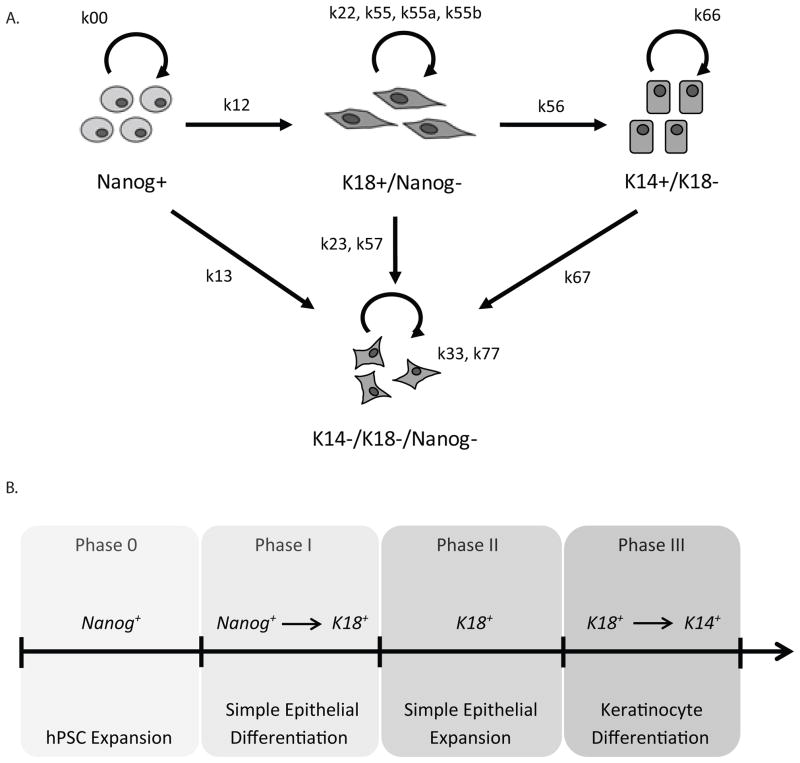

In this study, we investigated two robust epithelial differentiation protocols that yield K18+ simple epithelial cells and, subsequently, K14+ keratinocyte progenitors (Lian et al. 2013; Metallo et al. 2010). A population is comprised of several proliferating subpopulations (Prudhomme et al. 2004). Therefore, it is essential to quantitatively analyze the numbers of cells in each subpopulation and transitions between these subpopulations. We have defined distinct cell types present throughout both epithelial differentiation systems and illustrated the self-renewal and differentiation processes associated with these various cell subpopulations (Fig. 1A). Both differentiation protocols involved an initial commitment of hPSCs, identified by expression of Nanog, to an epithelial progenitor cell, identified as a cell that expresses K18 but not Nanog. The K18+/Nanog− simple epithelial cells further differentiated to epidermal keratinocyte progenitors, which expressed K14 but lost expression of K18 and Nanog. We have also universally defined an undesirable cell population as one that consists of cells that do not express K14, K18, or Nanog. Given these identifiable stable cell states, we monitored the dynamics of each of these cell subpopulations throughout differentiation.

Figure 1.

Establishment of cell states and compartmentalization of differentiation processes. A) Schematic representing the four cell states present during epithelial differentiation and the protein markers used to distinguish each cell state. Arrows indicate self-renewal or differentiation events among the various subpopulations. Rate constants representing either self-renewal or differentiation rates are also indicated. B) Schematic illustrating the compartmentalization of the differentiation process. Each phase is defined by a specific microenvironment and the primary differentiation or expansion event for each phase is indicated.

Each cell subpopulation has distinct self-renewal, differentiation, and apoptosis rates that are dependent upon the microenvironment. Both differentiation processes, Protocols 1 and 2, involve multiple changes in culture conditions, and therefore a dynamic cellular microenvironment, throughout differentiation. For this reason, we have compartmentalized these differentiation processes into multiple phases, each phase defined by a specific set of culture conditions (Fig. 1B, Table I). Such compartmentalization has been incorporated into other cell differentiation models (Glauche et al. 2007). We have defined Phase 0 as the maintenance and expansion of undifferentiated hPSCs. Phase I is the initial commitment of hPSCs to an epithelial cell fate resulting in K18+/Nanog− simple epithelial cells. The expansion of these simple epithelial cells occurs in Phase II. In Protocol 2, there is an additional phase of differentiation, Phase IIIa, involving a different set of culture conditions in which the K18+/Nanog− cells expand. Finally, Phase III involves the maturation of a K18+/Nanog− simple epithelial cell to a final cell type, K14+/K18−/Nanog− keratinocyte progenitor cells.

Table I.

Description of each differentiation phase for two epithelial differentiation protocols. Duration (in hours) and culture conditions (culture medium/substrate) for each differentiation phase are reported.

| Differentiation Phase | Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Conditions | Duration | Conditions | |

| 0 | 72 | mTeSR1/Matrigel | 72 | mTeSR1/Matrigel |

| I | 168 | UM+RA/Matrigel | 72 | UM+SU/Matrigel |

| II | 240 | K-DSFM/Gelatin | 144 | K-DSFM+5%FBS/Matrigel |

| IIIa | N/A | N/A | 96 | UM+RA+BMP4/Matrigel |

| III | 240 | K/DSFM/Gelatin | 240 | K-DSFM/Matrigel |

For each phase, we obtained cell subpopulation dynamics data by multiplying the absolute number of cells in culture by the percentage of cells in each subpopulation, obtained via flow cytometry. Subsequently, we fit a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to these data representing accumulation of the different cell types present in culture. A universal form of an ODE representing a cell subpopulation accumulation consists of first-order terms representing self-renewal, differentiation, or apoptosis and a maximum capacity limit representing the physical boundaries of the culture system, and thus providing a second-order relation:

| (1) |

where Ci is the concentration, or density, of cell type i in culture, C∞ is the maximum density of cells that can be present in culture, ΣC is the total number of cells in culture, kii is the net self-renewal rate (proliferation minus cell death) constant for cell type i, Ca is the concentration or density of cell type a in culture, kai is the differentiation rate constant representing conversion of cell type a into cell type i, and kij is the differentiation rate constant representing conversion of cell type i to cell type j or the apoptosis rate of cell type i. Using parameter estimation, we calculated the rate constants that represent the various cell fate decisions for each cell subpopulation. We have assumed that all parameters are dependent upon the specific microenvironmental conditions and are independent of time (Prudhomme et al. 2004). A description of each cell subpopulation’s parameter set and the differentiation phase in which it is estimated is tabulated in Table II. We fit these ODEs to kinetic data collected in each phase of both differentiation systems to eventually identify which cell fate decisions may be limiting overall cell yield.

Table II.

Description of cell fate decision rate constants estimated via model fits. All rate constants (parameters) are in units of hr−1.

| Rate constant | Differentiation Phase | Description |

|---|---|---|

| k00 | 0 | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells |

| k11 | I | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells |

| k12 | I | Differentiation of Nanog+ cells to K18+ cells |

| k13 | I | Differentiation of Nanog+ cells to Nanog−/K18− cells |

| k22 | I | Self-renewal of K18+ cells |

| k23 | I | Differentiation of K18+ cells to Nanog−/K18− cells |

| k33 | I | Self-renewal of Nanog−/K18− cells |

| k24 | I* | Apoptotic commitment of K18+ cells |

| k55a | II | Self-renewal of K18+ cells |

| k55b | IIIa* | Self-renewal of K18+ cells |

| k55 | III | Self-renewal of K18+ cells |

| k56 | III | Differentiation of K18+ cells to K14+ cells |

| k57 | III | Differentiation of K18+ cells to K14−/K18− cells |

| k66 | III | Self-renewal of K14+ cells |

| k67 | III | Differentiation of K14+/K18− cells to K14−/K18− cells |

| k77 | III | Self-renewal of K14−/K18− cells |

Indicates exclusive applicability to Protocol 2

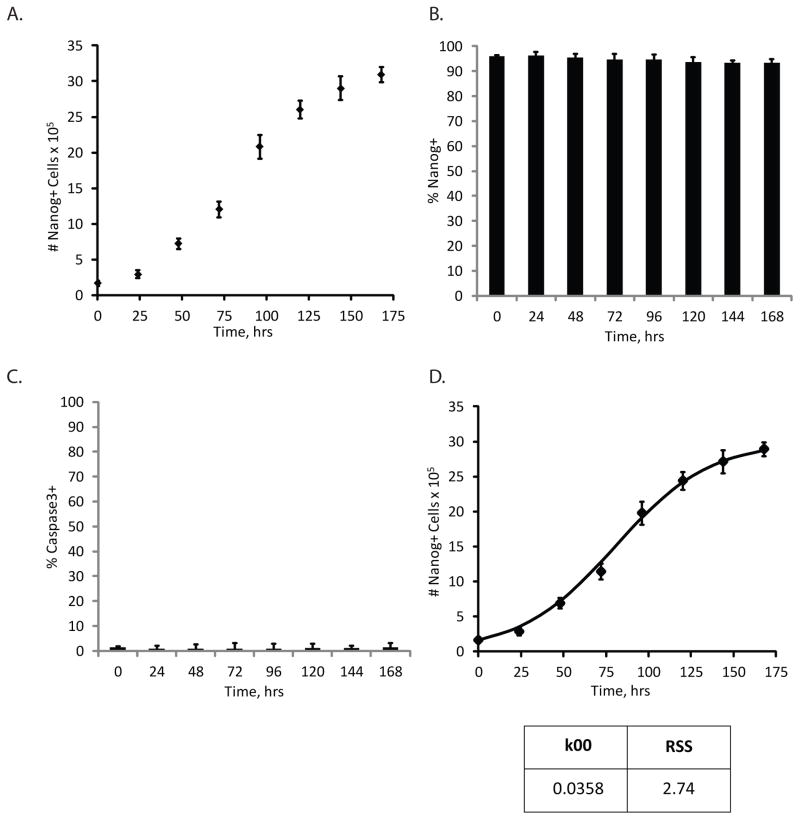

Phase 0: hPSC Expansion (Nanog+)

We first investigated the expansion of H9 hESCs in a pluripotent state prior to differentiation. In Phase 0, we monitored kinetics of cell growth by counting the number of cells at various time points (Fig. 2A) and quantifying the percentage of cells that were Nanog+ (Fig. 2B). No significant apoptosis was detected in Nanog+ cells by co-staining for the active form of caspase 3 (Fig. 2C). We then plotted the dynamics of Nanog+ cell expansion as a function of time and fit an ODE model representing Nanog+ cell growth, Equation S1, to estimate the self-renewal rate of Nanog+ cells in Phase 0 (Fig. 2D). The growth rate of Nanog+ cells in this phase was determined to be 0.0358 hr−1, or in other words, this population was estimated to have a doubling time of about 19.6 hours, similar to reported doubling times of hESCs under similar conditions (Harb et al. 2008; Nagaoka et al. 2010). These results were applied to analysis of both Protocols 1 and 2 since hPSC expansion conditions were identical for each differentiation method prior to Phase I.

Figure 2.

Analysis of hPSC expansion (Phase 0). A) Total cell number as a function of time in Phase 0. B) Flow cytometry data representing population breakdown as a function of time in terms of percentage cells expressing Nanog. C) Total apoptosis levels in culture as a function of time as measured by percentage of cells expressing the active form of caspase3. D) Model fit to data where data points represent the total number of Nanog+ H9 hESCs in culture as a function of time in the Phase 0 culture conditions. Line represents model fit to data by estimating the self-renewal rate of Nanog+ cell growth (k00). k00 value (in hr−1) and quality of fit, indicated by the residual sum of squares (RSS) value, are denoted. Error bars represent standard deviation (N=3).

Phase I: Initial Commitment to Progenitor State (K18+/Nanog−)

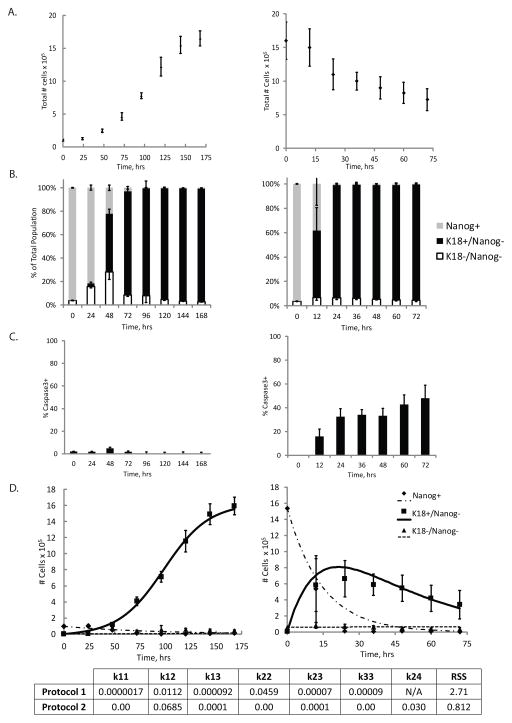

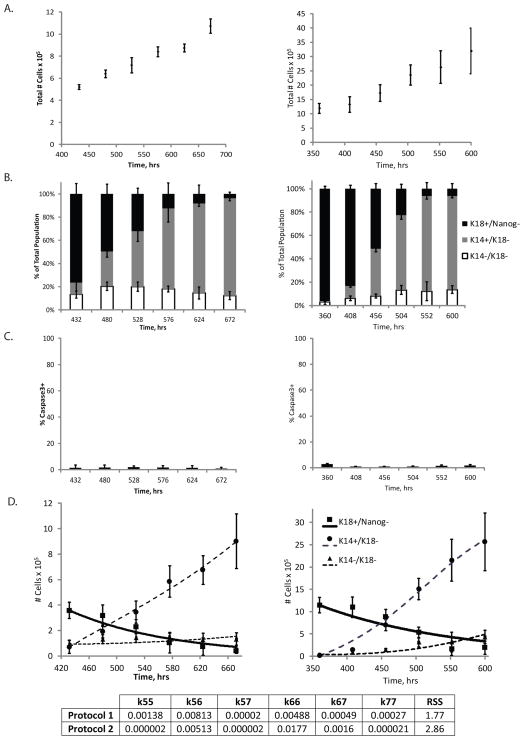

We next investigated the commitment of hPSCs toward an epithelial cell fate where an enriched Nanog+ population generates a population enriched in K18+/Nanog− cells. The kinetic data showing absolute cell counts as a function of time are clearly different in Protocol 1 (Fig. 3A-left panel) and Protocol 2 (Fig. 3A-right panel) since differentiation in the two protocols is initiated at different hPSC densities. However, in both systems, the kinetics of loss of Nanog expression and acquisition of K18 expression were similar (Fig. 3B, S1A, B). One striking difference we found between the two protocols was the substantially greater percentage of apoptotic cells in Protocol 2. Whereas apoptosis levels were minimal (<5%) in Protocol 1 (Fig. 3C-left panel, S1C), these levels ranged from 20% to 40% in Protocol 2 (Fig. 3C-right panel, S1C). While the net self-renewal rate of these K18+/Nanog− accounted for this cell death, we decoupled this apoptosis rate from the self-renewal rate by incorporating a cell death term (k24) in the Phase I analysis of Protocol 2. We fit a set of ODE equations, Equations S2–S4, to these data to estimate cell fate rate constants in Phase I for Protocol 1 (Fig. 3D-left panel) and Protocol 2 (Fig. 3D-right panel).

Figure 3.

Analysis of Phase I of epithelial differentiation. A) Total cell number as a function of time in Phase I for Protocol 1 (left) and Protocol 2 (right). B) Flow cytometry data representing population breakdown as a function of time in terms of the percentage of cells that express exclusively Nanog (grey), express K18, but not Nanog (black), or express neither marker (white) for Protocol 1 (left) and Protocol 2 (right). C) Apoptosis levels in culture as a function of time as measured by the percentage of the total number of cells expressing caspase3 in Protocol 1 (left) or the percentage of K18+/Nanog− cells expressing caspase3 in Protocol 2 (right). D) Model fits to data where data points represent cell subpopulation dynamics in Phase I. The total number of either Nanog+, K18+/Nanog−, or K18−/Nanog− cells in culture are plotted as a function of time during Phase I of Protocol 1 (left) or Protocol 2 (right). Lines represent model fits to data by estimating the various self-renewal and differentiation rates pertinent to this differentiation phase for each protocol. For Protocol 2, a death rate of the K18+/Nanog− cell population (k24) was incorporated into the model and estimated with the other cell fate decision rate constants. Values for each estimated rate constant (in hr−1) in each system, as well as the RSS value, are denoted. Error bars indicate standard deviation (N=3).

Rate constants estimated for Protocol 1 indicated that there was very little self-renewal of the Nanog+ cell population (k11). However, the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− population (k22) was estimated at 0.0459 hr−1, which was the by far the greatest value, and therefore the most dominant cell fate decision, estimated in this system (Fig. 3). In contrast, the model fit indicated that in Protocol 2, there was no significant self-renewal of any cell type and the system was primarily dominated by differentiation of Nanog+ cells to K18+/Nanog− cells (k12), with a value of 0.0685 hr−1, and apoptosis of K18+/Nanog− cells (k24), with a value of 0.030 hr−1. In addition, qualitatively, it is apparent that these two differentiation protocols resulted in vastly different cell subpopulation dynamics during the initial differentiation phase.

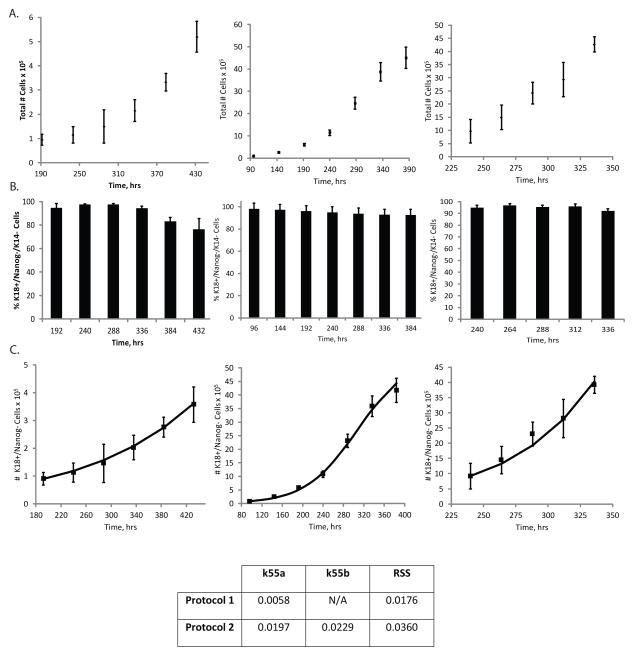

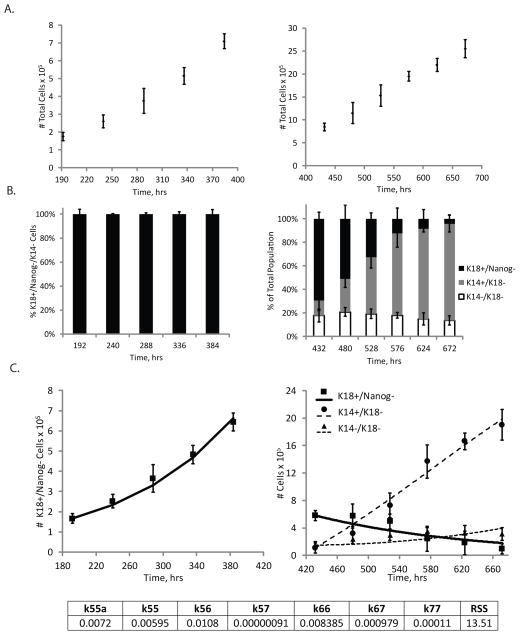

Phase II: Expansion of Progenitor Cells (K18+/Nanog−)

At the conclusion of Phase I in both epithelial differentiation platforms, cell populations were subcultured and plated in different culture conditions and therefore are exposed to a new microenvironment dictating the need for new cell fate parameters. This next phase, Phase II, involves the expansion of the cell population which is enriched in K18+/Nanog− epithelial progenitor cells. The total cell number (Fig. 4A-left and middle panels) and the purity of the K18+/Nanog− progenitor cell populations (Fig. 4B-left and middle panels, S2) were used to calculate the number of K18+/Nanog− cells as a function of time for Protocol 1 (Fig. 4C-left panel) and Protocol 2 (Fig. 4C-middle panel). We performed this analysis analogously to how we evaluated Phase 0 and Phase I. Equation S5 was used to fit the kinetic data and estimate the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− cells in protocol 1 (Fig 4C-left panel) and in protocol 2 (Fig 4C-middle panel). The self-renewal rate (k55a) of the K18+/Nanog− epithelial progenitors was over 3-fold greater in Phase II of Protocol 2 (0.0197 hr−1) than Protocol 1 (0.0058 hr−1). Phase II analysis of Protocol 2 was carried out for two weeks to estimate the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− cells (Fig 4C-middle panel), however the actual differentiation process truncates Phase II after six days of K18+/Nanog− cell expansion prior to entering the next phase of differentiation.

Figure 4.

Analysis of Phase II of epithelial differentiation. A) Total cell number as a function of time in Phase II for Protocol 1 (left), Protocol 2 (middle), and in Phase IIIa for Protocol 2 (right). B) Flow cytometry data representing population breakdown as a function of time in terms of the percentage of cells that express K18, but not Nanog or K14 for Phase II in Protocol 1 (left), Protocol 2 (middle), and Phase IIIa in Protocol 2 (right). C) Model fits to data where data points represent the total number of K18+/Nanog− cells in culture as a function of time during Phase II of either Protocol 1 (left) or Protocol 2 (middle). In addition, the number of K18+/Nanog− cells in Phase IIIa, an additional phase specific to Protocol 2, was analyzed (right). Lines represent model fits to data by estimating the self-renewal rates of the K18+/Nanog− cells in Phase II (k55a) or Phase IIIa (k55b). Values for the estimated rate constants (in hr−1), as well as the RSS value, are denoted. Error bars indicate standard deviation (N=3).

Following Phase II, Protocol 2 incorporated an additional phase, Phase IIIa, involving expansion of the K18+/Nanog− simple epithelial cells under different culture conditions (Table I). There is no equivalent phase in the differentiation system defined in Protocol 1. The self-renewal rate of these epithelial progenitor cells was estimated based on the fit of Equation S5 to kinetic data (Fig. 4C-right panel) obtained by total cell counts (Fig. 4A-right panel) and flow cytometry for the percentage of K18+/Nanog− cells (Fig. 4B-right panel, S2). The value of this epithelial progenitor’s self-renewal rate (k55b) was found to be 0.0229 hr−1, slightly greater than the self-renewal rate estimated in Phase II. Four days in Phase IIIa precedes the final phase of differentiation, Phase III.

Phase III: Differentiation to Final Cell State (K14+/K18−)

The final phase of differentiation, Phase III, directs the transition from a K18+/Nanog− epithelial progenitor cell to a K14+/K18− keratinocyte progenitor cell. Data showed steady increases in total cell population during both Protocol 1 (Fig. 5A-left panel) and Protocol 2 (Fig. 5A-right panel). Both systems also exhibited a monotonic increase in the fraction of K14+/K18− cells as a function of time during Phase III (Fig. 5B, S3). Caspase3 staining indicated low levels of apoptosis in both systems (<5%) (Fig. 5C), so cell fate parameters representing cell death were not included in this analysis. The set of ODEs representing the various cell subpopulations in culture in Phase III, Equations S6–S8, were fit to the cell subpopulation dynamics data to estimate the various cell fate parameter values in Protocol 1 (Fig. 5D-left panel) and Protocol 2 (Fig. 5D-right panel). As opposed to Protocol 1 (k55=0.00138 hr−1), the estimated values obtained for Protocol 2 indicated minimal K18+/Nanog− self-renewal (k55 = 0.000002 hr−1). Protocol 2 was estimated, however, to have a greater rate of K14+/K18− self-renewal (k66=0.0177 hr−1) as opposed to Protocol 1 (k66=0.00488 hr−1). By comparison, both systems exhibited similar differentiation rates (k56) representing the conversion rate of K18+/Nanog− cells to K14+/K18− cells in Protocol 1 (0.00813 hr−1) and Protocol 2 (0.00513 hr−1). Ultimately, an analysis of how these individual cell fate parameters affect overall K14+/K18− cell yield is required to 1) determine which cell fate decisions may be limiting to this overall differentiation process and 2) at which cell state would it be most advantageous to expand the population to optimize yield and purity of the desired cell population. In addition, such an analysis would serve as a means to compare the limits of the two differentiation systems analyzed here and which protocol may be more feasible for a scale-up application.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Phase III of epithelial differentiation. A) Total cell number as a function of time in Phase I for Protocol 1 (left) and Protocol 2 (right). B) Flow cytometry data representing population breakdown as a function of time in terms of the percentage of cells that express exclusively K18, but not Nanog or K14 (black), cells that express K14, but not K18 (dark grey), or cells that express none of these markers (white) for Protocol 1 (left) and Protocol 2 (right). C) Apoptosis levels in culture as a function of time as measured by the percentage of the total number of cells expressing caspase3 in Protocol 1 (left) or in Protocol 2 (right). D) Model fit to data where data points represent cell subpopulation dynamics in Phase III. The total number of either K18+/Nanog−, K14+/K18−, or K14−/K18− cells in culture are plotted as a function of time during Phase III of either Protocol 1 (left) or Protocol 2 (right). Lines represent model fits to data by estimating the various self-renewal and differentiation rates pertinent to this differentiation phase for each protocol. Values for each estimated rate constant (in hr−1) in each system, as well as the RSS value, are denoted in the table. Error bars indicate standard deviation (N=3).

Sensitivity Analyses

One primary objective of our study was to determine which cell fate parameters limit the yield of a desired cell population, in this case K14+/K18− cells. By performing a sensitivity analysis on each individual parameter estimated from each phase of differentiation, we determined the most influential parameters on our final keratinocyte progenitor yield:

| (2) |

where sij(tk) is the sensitivity of output i at time k on parameter j, dxi(tk) is the resulting change in output i at time k given the change in parameter j, pj is the present value of parameter j, dpj is the change in parameter j, and xi(tk) is the present value of output i at time k. Here, we set the output (xi(tk)) as the yield of K14+/K18− keratinocyte progenitors at the conclusion of the differentiation process. We varied each parameter individually with a 10% change (dpj/pj=0.1) and calculated the resulting sensitivity value in each protocol.

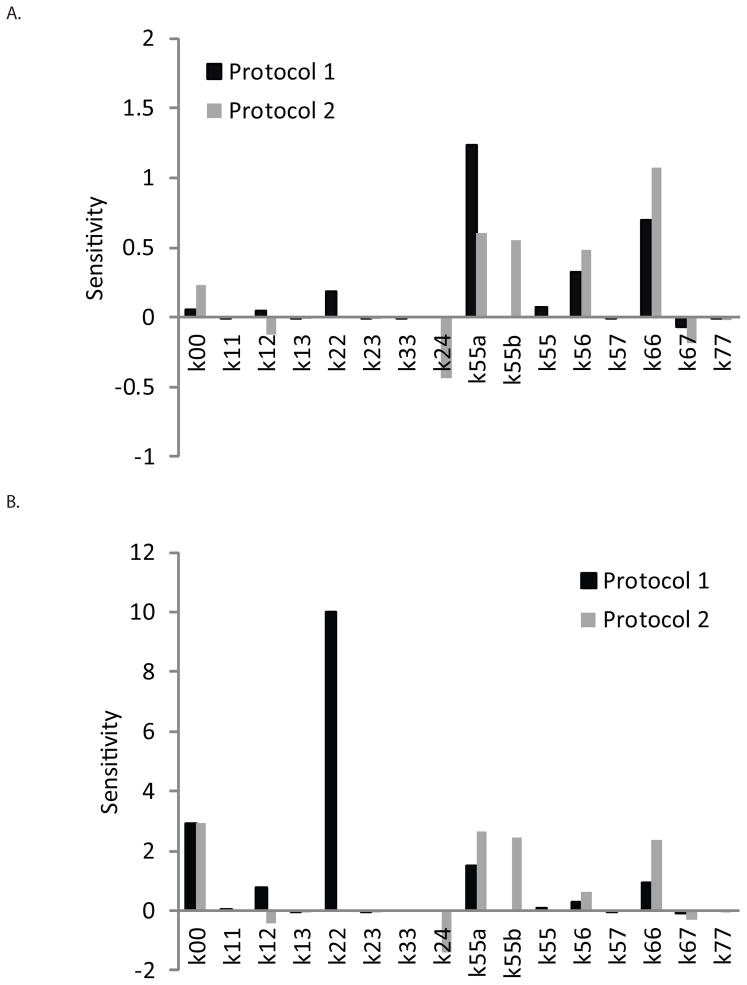

Sensitivity analyses are shown for each of the two epithelial differentiation systems (Fig. 6A, Table III). The results indicate that for Protocol 1, the final yield of K14+/K18− cells was most sensitive to changes in the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− epithelial progenitor cells during Phase II of differentiation (k55a). In contrast, the final yield in Protocol 2 was most sensitive to the self-renewal rate of the final K14+/K18− cell type (k66). The model also predicts that other cell fate parameters such as the differentiation rate of the K18+/Nanog− cells to the K14+/K18− cells (k56) or the self-renewal rate of the K14+/K18− cells (k66), in the case of Protocol 1, can also have a significant impact on overall K14+/K18− cell yield. In the case of Protocol 2, increasing self-renewal of the K18+/Nanog− cells in either Phase II (k55a) or Phase IIIa (k55b) or the differentiation rate of the K18+/Nanog− cells to the K14+/K18− cells (k56) was predicted to have a significant impact on K14+/K18− cell yield. Altering the microenvironment to decrease the death rate of K18+/Nanog− cells in Phase I (k24) in Protocol 2 would also benefit K14+/K18− cell yield. These analyses are based on the maximum capacity constraints of the lab-scale system that we analyzed.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of epithelial differentiation protocols. Sensitivity values were calculated to determine the impact of a 10% change in an individual parameter to the resulting K14+/K18− cell yield as predicted by the model. A comparison between the sensitivity values for each of the two protocols is shown in either A) the lab-scale system analyzed with a maximum capacity or B) a hypothetical unconstrained system lacking a maximum capacity assumption.

Table III.

Summary of critical cell fate decisions in each phase of differentiation for both protocols.

| Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 0 | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells |

| Phase I | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells | Cell death of K18+/Nanog− cells |

| Phase II | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells |

| Phase III | Self-renewal of K14+/K18− cells | Self-renewal of K14+/K18− cells |

The most critical cell fate decision for the entire differentiation process is indicated in bold for each protocol.

We next investigated the sensitivity of overall keratinocyte progenitor yield on the various cell fate parameters by releasing the maximum capacity constraints on our system to simulate a hypothetical large-scale process that may not have the same physical barriers to cell growth that is present in a 9.5 cm2 cell culture well. In removing the maximum capacity limit and therefore reducing the contact inhibition of growth imposed on the cells, we generated new sensitivity values for each individual parameter (Fig. 6B, Table IV). In Protocol 1, we observed a striking difference in which parameters had the greatest impact on keratinocyte progenitor yield. In a system with no maximum capacity limits, changes in the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− progenitor cells in Phase I (k22) had the greatest impact on overall cell yield. This suggests that in an unconstrained system, one should aim to improve K14+/K18− cell yield by changing the microenvironment in Phase I to facilitate a higher K18+/Nanog− self-renewal rate. In addition, the K18+/Nanog− progenitor cells in Phase I would be the most advantageous cell state for expansion to scale-up epithelial cell production. Protocol 2 does not have a single dominant parameter that, if changed, is predicted to drastically affect overall K14+/K18− cell yield. Rather, five parameters (k00, k24, k55a, k55b, k66) are predicted to have a comparable impact on keratinocyte progenitor yield. Unlike the conditions with a maximum capacity limit, it appears that there is no clear cell state that is most advantageous for scale-up and expansion for Protocol 2 but there instead exist multiple states that regulate K14+/K18− cell yield.

Table IV.

Summary of critical cell fate decisions in each phase of differentiation for both protocols in a hypothetical system without a maximum capacity limit.

| Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 0 | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells | Self-renewal of Nanog+ cells |

| Phase I | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells | Cell death of K18+/Nanog− cells |

| Phase II | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells |

| Phase III | Self-renewal of K18+/Nanog− cells | Self-renewal of K14+/K18− cells |

The most critical cell fate decision for the entire differentiation process is indicated in bold for each protocol.

Model Validation with Microenvironmental Change

The sensitivity analyses predicted which cell fate decisions were potentially limiting K14+/K18− epidermal keratinocyte progenitor yield in the two differentiation processes. We next sought to validate these model predictions by changing the microenvironment in such a way to influence specific cell fate decisions and identify the resulting changes in overall keratinocyte progenitor yield. Specifically, we targeted the self-renewal rate of the K18+/Nanog− cells in Phase II of Protocol 1 (k55a) since this rate was predicted to limit the yield of K14+/K18− cells (Fig. 6A). To alter the microenvironment, we cultured these cells on Synthemax plates rather than gelatin-coated plates since we have previously found this substrate to facilitate greater proliferation of these simple epithelial cells (Selekman et al. 2013). We collected kinetic data on the total number of cells in culture (Fig. 7A-left panel) and the composition of the population (Fig. 7B-left panel). We fit the same ODE model to these data as was done in the Phase II analysis discussed previously. In fitting this model to the cell subpopulation dynamics data, we estimated the self-renewal of the K18+/Nanog− simple epithelial cells to be 0.0072 hr−1 (Fig. 7C-left panel), about 25% higher than what was calculated for these same cells on a gelatin substrate (Fig. 4C-left panel). Given this change, the model predicted an overall K14+/K18− keratinocyte progenitor yield of about 1.3 million cells on Synthemax compared to 0.90 million cells when cultured on gelatin-coated plates. However, our experimental yield was actually 1.90 ± 0.31 million keratinocyte progenitor cells, indicating that other cell fate decisions were potentially altered by changing the substrate from gelatin to Synthemax.

Figure 7.

Effect of microenvironmental changes on estimated cell fate parameters and overall epithelial cell yield. A Synthemax substrate was used in lieu of a gelatin substrate and data was collected to show A) total cell number in Phase II (left) and Phase III (right) as a function of time. B) Flow cytometry data demonstrating high purity K18+/Nanog− cells during Phase II (left) and the population breakdown as a function of time in terms of the percentage of cells that express exclusively K18, but not Nanog or K14 (black), cells that express K14, but not K18 (dark grey), or cells that express none of these markers (white) during Phase III (right). Cell subpopulation dynamics data were collected and fit to corresponding models in Phase II (left) and Phase III (right) of Protocol 1. Estimated rate constant values (in hr−1) in each phase are denoted as well as the RSS value for the model fit. Error bars indicate standard deviation (N=3).

To identify other cell fate parameters that culture on Synthemax changed, we investigated cell fate transitions during Phase III of Protocol 1 on a Synthemax substrate. Analogous to our investigation of a modified Phase II described above, we collected kinetic data on absolute cell number in culture (Fig. 7A-right panel) and the population composition (Fig. 7B-right panel). We fit these data to the same set of ODEs used in our original Phase III analysis of Protocol 1 and surprisingly found that Synthemax increased the differentiation rate of K18+/Nanog− cells into K14+/K18− cells to 0.00813 hr−1 as well as the self-renewal rate of the K14+/K18− cells to 0.00488 hr−1 (Fig 7C-right panel). Both of these parameters were predicted to have a significant effect on overall K14+/K18− cell yield, albeit a smaller impact relative to k55a (Fig. 6A). Given these changes, our model predicted a final K14+/K18− cell yield of 2.1 million, which was within the range of our experimental yield at 1.90 ± 0.31 million. In identifying specific cell fate decisions found to be bottlenecks of differentiation, we successfully demonstrated to facilitate changes in these cell fate decisions by altering the microenvironment, which, as our model predicted, would result in a greater keratinocyte progenitor yield.

Discussion

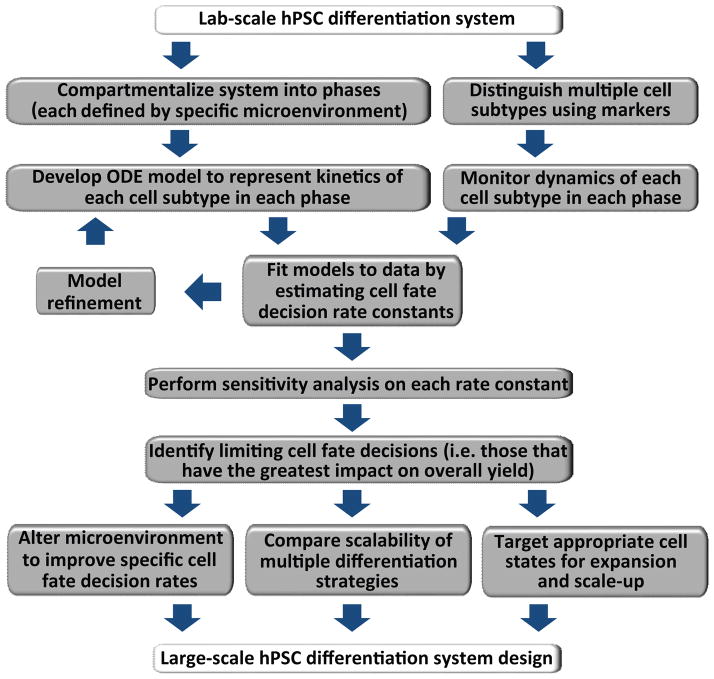

Here, we have outlined a novel approach for improving the efficiency or investigating the scalability of an established lab-scale hPSC differentiation process. The process of compartmentalizing a differentiation system based on distinct changes in cellular microenvironments and defining different cell subpopulations present in culture allows identification of the cell fate decisions that may limit yield of a differentiated cell population (Fig. 8). In collecting cell subpopulation dynamics data and fitting a set of ODEs representing the kinetics of the differentiation process, we were able to decouple the rate constants of the various cell fate decisions (self-renewal, differentiation, apoptosis) in two different differentiation systems to generate a similar cell type. By performing a sensitivity analysis on these different cell fate parameters, we predicted which parameters would have the greatest effect on overall cell yield of our desired epithelial cell type in our lab-scale system and in a hypothetical large-scale system. Finally, we were able to validate our model by altering the microenvironment to facilitate changes in cell fate decisions that enhanced keratinocyte progenitor yield. The approach outlined in this study should be applicable to any established lab-scale system involving the engineering of hPSCs to generate populations of a desired cell type in which there is a desire to scale-up to meet industrial or clinical demands for such cell types.

Figure 8.

Schematic representing an approach to investigating efficiency and scalability of laboratory-scale hPSC differentiation protocols. Gray boxes represent the strategy outlined throughout this study to bridge the gap between laboratory differentiation systems and bioprocess design and improvements.

The ability to distinguish multiple stable or metastable cells states in culture is imperative for this analysis and such information is required to apply this method to other stem cell differentiation systems. However, it is important to highlight a few key assumptions made in this study. We assumed that all parameters were independent of time. In reality, time-dependent changes in total cell number and the varying composition of cells could conceivably have an impact on cell fate decision rates. Temporal changes in cell-cell contact and paracrine signaling in each differentiation phase can alter the microenvironment resulting in dynamic changes in cell fate decision rates. However, without prior knowledge as to how these rates would individually change as a function of total cell number or population composition, it is difficult to incorporate this consideration into the model. The framework outlined in this study is conducive for model refinement in the event additional complexities or nuances of specific differentiation systems are well understood.

Another assumption we made in this study was to characterize Nanog−/K18−/K14− cells as a single subpopulation of undesired cells with distinct self-renewal and differentiation rates. While it is likely that this population was comprised of a heterogeneous mixture of cells, we did not further characterize this population was given its relatively low abundance in culture. Distinguishing multiple discrete undesired cell types, however, might be necessary for other differentiation processes, however.

In fitting ODE-based models to our population dynamics data, we were able to decouple the rates of various cell fate decisions for each subpopulation using parameter estimation similar to what has been performed in other cell-based contexts (Ackleh and Thibodeaux 2008; Task et al. 2012). The parameter sensitivity analyses were limited to the cell fate decision rates and did not include analysis of parameters such as plating efficiency during subculture or time spent in the different differentiation phases. While these are also important factors in determining overall differentiation efficiency and could be investigated using a similar approach, we specifically focused on cell fate decisions for insight into which of these cellular processes were most integral to differentiation efficiency and, potentially, scale-up applications.

For two distinct epithelial differentiation protocols, we identified which cell fate processes may be bottlenecks to the differentiation process, and therefore should be targeted for improvement in epithelial cell yield. Others have also targeted bottlenecks of stem cell differentiation processes to improve differentiation efficiency or yield. For example, in an elegant study, Ungrin et al. identified a parameter representing cell yield loss and specifically targeted this parameter to improve efficiency of definitive endoderm progenitors from hPSCs (Ungrin et al. 2012). The use of ROCK inhibitor, Y27632, to prevent this yield loss due to cell death resulted in a 36-fold increase in cell yield. In another set of studies, embryoid bodies (EBs) derived from hESCs in porous alginate scaffolds were shown to have twofold better viability and reported better proliferation in a slow turning lateral vessel bioreactor compared to EBs in static culture (Gerecht-Nir et al. 2004a; Gerecht-Nir et al. 2004b). These studies illustrate how microenvironmental changes facilitated improvement in overall cell yield via changes in cell fate decision rates or efficiency.

The output generated from the approach described here could be used for bioreactor design for large-scale differentiation processes. Additionally, the analysis performed in this study could also be applied to small or scalable bioreactors for hPSC growth and differentiation (Cameron et al. 2006; Côme et al. 2008; Fernandes et al. 2009; Gerecht-Nir et al. 2004a; Gerecht-Nir et al. 2004b; Kehoe et al. 2010; Krawetz et al. 2010; Lock and Tzanakakis 2009; Nie et al. 2009; Niebruegge et al. 2009; Oh et al. 2009; Shafa et al. 2012). Further experimentation to determine actual technical feasibility of scaling-up (i.e. applicability of scalable stem cell culture technology such as microcarriers (Jing et al. 2010; Tang et al. 2012; Wilson and McDevitt 2013) to facilitate differentiation and expansion) is out of the scope of this study, yet is equally crucial to large-scale bioreactor design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the University of Wisconsin’s Carbone Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Laboratory for the use of their services. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant CBET-1066311 (S.P.P.), a University of Wisconsin Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Predoctoral Fellowship (J.A.S.), and a National Institutes of Health training grant NIDCD T32 DC009401 (J.A.S.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Aberdam E, Barak E, Rouleau M, de LaForest S, Berrih-Aknin S, Suter D, Krause K, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Aberdam D. A pure population of ectodermal cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(2):440–4. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackleh AS, Thibodeaux JJ. Parameter estimation in a structured erythropoiesis model. Math Biosci Eng. 2008;5(4):601–16. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2008.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarin SM, Palecek SP. Development of Scalable Culture Systems for Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Biochem Eng J. 2010;48(3):378. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita GJ, Ferreira BS, da Silva CL, Gonçalves R, Almeida-Porada G, Cabral JM. Hematopoietic stem cells: from the bone to the bioreactor. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21(5):233–40. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CM, Hu WS, Kaufman DS. Improved development of human embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies by stirred vessel cultivation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;94(5):938–48. doi: 10.1002/bit.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côme J, Nissan X, Aubry L, Tournois J, Girard M, Perrier AL, Peschanski M, Cailleret M. Improvement of culture conditions of human embryoid bodies using a controlled perfused and dialyzed bioreactor system. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14(4):289–98. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellatore SM, Garcia AS, Miller WM. Mimicking stem cell niches to increase stem cell expansion. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19(5):534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324(5935):1673–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AM, Marinho PA, Sartore RC, Paulsen BS, Mariante RM, Castilho LR, Rehen SK. Successful scale-up of human embryonic stem cell production in a stirred microcarrier culture system. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42(6):515–22. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerecht-Nir S, Cohen S, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Bioreactor cultivation enhances the efficiency of human embryoid body (hEB) formation and differentiation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004a;86(5):493–502. doi: 10.1002/bit.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerecht-Nir S, Cohen S, Ziskind A, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Three-dimensional porous alginate scaffolds provide a conducive environment for generation of well-vascularized embryoid bodies from human embryonic stem cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004b;88(3):313–20. doi: 10.1002/bit.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauche I, Cross M, Loeffler M, Roeder I. Lineage specification of hematopoietic stem cells: mathematical modeling and biological implications. Stem Cells. 2007;25(7):1791–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harb N, Archer TK, Sato N. The Rho-Rock-Myosin signaling axis determines cell-cell integrity of self-renewing pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeltine LB, Selekman JA, Palecek SP. Engineering the human pluripotent stem cell microenvironment to direct cell fate. Biotechnol Adv. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KJ, Shamis Y, Carlson MW, Aberdam E, Aberdam D, Garlick JA. Three-dimensional epithelial tissues generated from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(11):3417–26. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Kiuru M, Cairo MS, Christiano AM. Generation of keratinocytes from normal and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa-induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(21):8797–802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100332108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing D, Parikh A, Tzanakakis ES. Cardiac cell generation from encapsulated embryonic stem cells in static and scalable culture systems. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(11):1397–412. doi: 10.3727/096368910X513955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe DE, Jing D, Lock LT, Tzanakakis ES. Scalable stirred-suspension bioreactor culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(2):405–21. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirouac DC, Zandstra PW. Understanding cellular networks to improve hematopoietic stem cell expansion cultures. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17(5):538–47. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawetz R, Taiani JT, Liu S, Meng G, Li X, Kallos MS, Rancourt DE. Large-scale expansion of pluripotent human embryonic stem cells in stirred-suspension bioreactors. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16(4):573–82. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X, Selekman J, Bao X, Hsiao C, Zhu K, Palecek SP. A small molecule inhibitor of SRC family kinases promotes simple epithelial differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e60016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock L, Tzanakakis E. Expansion and Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells to Endoderm Progeny in a Microcarrier Stirred-Suspension Culture. Tissue Engineering Part a. 2009;15(8):2051–2063. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo C, Azarin S, Ji L, de Pablo J, Palecek S. Engineering tissue from human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2008a;12(3):709–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo C, Ji L, de Pablo J, Palecek S. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to epidermal progenitors. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;585:83–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-380-0_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo CM, Ji L, de Pablo JJ, Palecek SP. Retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein signaling synergize to efficiently direct epithelial differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008b;26(2):372–80. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka M, Si-Tayeb K, Akaike T, Duncan SA. Culture of human pluripotent stem cells using completely defined conditions on a recombinant E-cadherin substratum. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Bergendahl V, Hei DJ, Jones JM, Palecek SP. Scalable culture and cryopreservation of human embryonic stem cells on microcarriers. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25(1):20–31. doi: 10.1002/btpr.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebruegge S, Bauwens C, Peerani R, Thavandiran N, Masse S, Sevaptisidis E, Nanthakumar K, Woodhouse K, Husain M, Kumacheva E, et al. Generation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Mesoderm and Cardiac Cells Using Size-Specified Aggregates in an Oxygen-Controlled Bioreactor. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2009;102(2):493–507. doi: 10.1002/bit.22065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SK, Chen AK, Mok Y, Chen X, Lim UM, Chin A, Choo AB, Reuveny S. Long-term microcarrier suspension cultures of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2(3):219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudhomme WA, Duggar KH, Lauffenburger DA. Cell population dynamics model for deconvolution of murine embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation responses to cytokines and extracellular matrix. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88(3):264–72. doi: 10.1002/bit.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selekman JA, Grundl NJ, Kolz JM, Palecek SP. Efficient generation of functional epithelial and epidermal cells from human pluripotent stem cells under defined conditions. Tissue Engineering Part C. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0011. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra M, Brito C, Correia C, Alves PM. Process engineering of human pluripotent stem cells for clinical application. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):350–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafa M, Sjonnesen K, Yamashita A, Liu S, Michalak M, Kallos MS, Rancourt DE. Expansion and long-term maintenance of induced pluripotent stem cells in stirred suspension bioreactors. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6(6):462–72. doi: 10.1002/term.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Chen W, Weir MD, Thein-Han W, Xu HH. Human embryonic stem cell encapsulation in alginate microbeads in macroporous calcium phosphate cement for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(9):3436–45. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task K, Jaramillo M, Banerjee I. Population based model of human embryonic stem cell (hESC) differentiation during endoderm induction. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro S, Waknitz M, Swiergiel J, Marshall V, Jones J. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungrin MD, Clarke G, Yin T, Niebrugge S, Nostro MC, Sarangi F, Wood G, Keller G, Zandstra PW. Rational bioprocess design for human pluripotent stem cell expansion and endoderm differentiation based on cellular dynamics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109(4):853–66. doi: 10.1002/bit.24375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S, Davey RE, Cheng D, Raghu RC, Lauffenburger DA, Zandstra PW. Clonal evolution of stem and differentiated cells can be predicted by integrating cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic parameters. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2005;42(Pt 2):119–31. doi: 10.1042/BA20040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JL, McDevitt TC. Stem cell microencapsulation for phenotypic control, bioprocessing, and transplantation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110(3):667–82. doi: 10.1002/bit.24802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik M, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane J, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir G, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandstra PW, Lauffenburger DA, Eaves CJ. A ligand-receptor signaling threshold model of stem cell differentiation control: a biologically conserved mechanism applicable to hematopoiesis. Blood. 2000;96(4):1215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.