SUMMARY

Hyperacusis can be a prominent and disabling symptom of superior semicircular canal dehiscence associated with autophony and the Tullio phenomenon. We report three clinical cases characterized by disabling hyperacusis in which semicircular canals dehiscence was excluded by temporal bone high-resolution computed tomography. The images disclosed lateral semicircular canal dysplasia, characterized by a small bony island, and dilatation of both the anterior and the posterior arms of the lateral semicircular canal. Cochleo-vestibular examinations (pure tone audiometry, infra-red videonystagmoscopy, vibration-induced nystagmus test, vestibular evoked myogenic potentials) will also be described. To verify the transtympanic ventilation tube effect, bilateral myringotomies tubes were performed in one patient but no long lasting subjective benefit was noted. Concerning the pathophysiology of this condition, we hypothesized that the increased volume of inner ear liquid can modify the micromechanical function of the cochlea and the labyrinthine hydrodynamics. In conclusion, in the case of specific symptoms, such as hyperacusis, it is important to consider the possibility of an inner ear morphological alteration involving the lateral canal and vestibule structures, as well as the existence of bony semicircular canal dehiscence.

KEY WORDS: Hyperacusis, Inner ear malformation, Lateral canal dysplasia, Semicircular canal dehiscence, Vestibular aqueduct

RIASSUNTO

L'iperacusia può rappresentare un importante ed invalidante sintomo della deiscenza del canale semicircolare superiore, associato ad autofonia ed al fenomeno di Tullio. Riportiamo tre casi clinici caratterizzati da iperacusia invalidante in cui deiscenze dei canali semicircolari furono escluse dallo studio TAC ad alta risoluzione delle rocche petrose. Lo studio radiologico rilevò una displasia del canale semicircolare laterale, caratterizzata da una isola ossea ridotta e dilatazione sia del braccio anteriore che di quello posteriore. Descriveremo gli elementi provenienti dalle indagini cocleo-vestibolari effettuate (esame audiometrico tonale liminare, videoculoscopia, test vibratorio mastoideo, studio dei potenziali evocati vestibolari miogeni). In un paziente è stato tentato un trattamento con drenaggio transtimpanico bilateralmente senza alcun beneficio duraturo. Per quanto concerne la fisiopatologia del fenomeno, noi ipotizziamo che l'aumento di volume dei liquidi dell'orecchio interno possa modificare la micromeccanica della coclea e l'idrodinamica labirintica. Concludendo, in caso di un sintomo specifico come l'iperacusia, è importante considerare la possibilità di una malformazione che coinvolga il canale semicircolare laterale e il vestibolo tanto quanto una deiscenza della capsula otica.

Introduction

Hyperacusis is an auditory condition characterized by hypersensitivity and decreased tolerance to sounds, frequently concerning a definite range of frequencies 1. Patients with hyperacusis are also disturbed by low daily sounds, such as normal conversation, running water, flipping through pages, cooking, etc. Hyperacusis is frequently associated with tinnitus and emotional distress (above all anxiety) 2.

Although hyperacusis can be due to several pathologic conditions, some of which affect the neurological pathway (head injury, migraine, Lyme Disease, Williams syndrome) or the psychological/psychiatric apparatus (autistic spectrum disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia), it can also be part of the clinical spectrum of auditory and vestibular disorders 1 2. For example, it is a symptom described in acoustic shock injury, Meniere's disease, otosclerosis, perilymphatic fistula and Bell's Palsy, and can represent a prominent and disabling symptom of superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) associated with autophony and the Tullio phenomenon 3. No other inner ear malformations associated with hyperacusis have been described in the English literature.

In the present report, three clinical cases characterized by disabling hyperacusis in which SSCD was excluded by temporal bone high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) will be described. The images disclosed lateral semicircular canal (LSC) dysplasia, characterized by a small bony island, and dilatation of both the anterior and the posterior arms of the LSC.

Patients

Brief case histories of three patients with hyperacusis are herein presented. Standard clinical neuro-otological assessment was normal in all three patients. Otoscopy, puretone audiometry and acoustic reflexes established the existence of normal hearing function (no evidence of sensorineural, conductive or mixed hearing loss). Infra-red videonystagmoscopy did not reveal either spontaneous or evoked nystagmus (head pitch test, Hallpike manoeuvre, bilateral mastoid 100 Hz-vibration, head shaking test and Valsalva manoeuvre with pinched nostrils).

Each patient was screened to exclude central nervous system and VIII cranial nerve enhancing lesions using contrast- enhanced brain MRI.

The temporal bone HRCT, performed on a multi-slice GE Medical Systems scanner, was completed by reformatted images (at 0.3 mm increments) along the Pöschl plane (parallel to the superior semicircular canal) and Stenver plane (perpendicular to the superior semicircular canal).

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man presented to our hospital complaining of a continuous sensation of hyperacusis of three years' duration, following an acoustic trauma (disco music exposition). Auditory symptoms, including left tinnitus, were also present. The anamnesis disclosed interesting elements, such as considerable intolerance to low sounds and vibrations, such as traffic, rain, background office noise, humming from the refrigerator, etc. He denied having had any notable cranial trauma in the past or a history of migraine headaches. In extreme situations, even the use of earplugs failed to bring relief and the patient had been spending his life trying to avoid all sounds and just staying at home. No vestibular symptom was present in his clinical history. Medical therapy was ineffective in relieving the tinnitus and hyperacusis. Pure tone audiometry established a normal hearing function in absence of negative bone conduction thresholds bilaterally.

The cochleo-vestibular evaluation was completed by cervical air-conducted vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (C-AC-VEMPs) testing which showed a normal threshold bilaterally (120 dB SPL). A very recent bithermal caloric test showed right canalar hypofunction.

Visual inspection of the temporal bone HRCT images disclosed a normal inner ear. However, careful analysis of the CT images excluded SSCD while disclosing the presence of bilateral dysplasia of the LSC (Fig. 1a). Both the cochlea and the vestibular aqueducts appeared normal in shape.

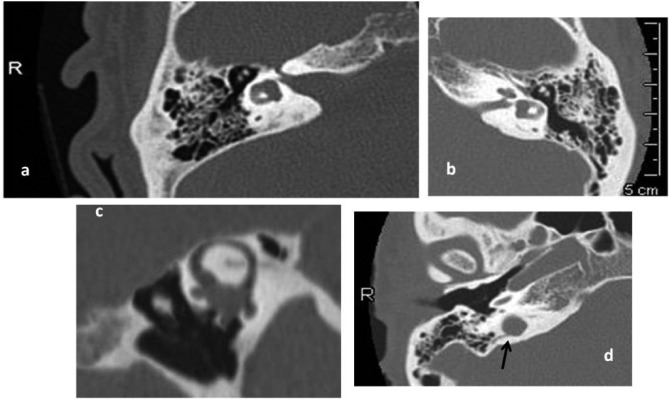

Fig. 1.

Temporal bone HRCT showing inner ear in of our series.

a) The axial CT sections of the right temporal bone of case 1, at the level of the internal auditory canal, show the LSC dysplasia; the small LSC bony island and the wide vestibule are clearly evident. b) The axial CT sections of the left temporal bone of case 2, at the level of the basal cochlear turn, show the LSC dysplasia: the lumen of the LSC anterior arm, like that of the posterior arm, is dilated. c) Temporal bone reformatted oblique CT images in the Pöschl plane (parallel to the right superior semicircular canal) of case 2, demonstrating the integrity of the cortical bone at the right arcuate eminence, even if thinner than normal. d) The axial CT sections of the right temporal bone of case 3, at the level of the basal cochlear turn, show the vestibular aqueduct erosion by the jugular bulb (black arrow).

Patient 2

A 70-year-old man presented to our hospital with a history of recurrent benign positional paroxysmal vertigo (BPPV) following a mild cranial trauma that occurred five years earlier; the BPPV involved the left posterior semicircular canal. The patient also described bilateral fullness, but pure tone audiometry established a slight age-related hearing loss bilaterally.

When he had undergone vestibular examination, particularly during bone conduction VEMPs testing (500 Hz TB, 6 msec, 1.0 V – delivered to each mastoid by a hand-held minishaker with an attached perspex rod [type 4810, Bruel and Kjaer P/L, Denmark]), he had vertigo and subsequent dizziness for some days thereafter. Since then, he had experienced disabling autophony resulting in difficulties in holding conversations, and hyperacusis associated with bilateral tinnitus and fullness. No other symptoms were reported. A normal threshold bilaterally (120 dB SPL on the right side and 115 dB SPL on the left side) was observed with C-AC-VEMPs testing. A bithermal caloric test was attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate it.

Temporal bone HRCT scans excluded the presence of dehiscence of the otic capsule, even if we noted a thinning of the cortical bone at the right arcuate eminence. Additional careful analysis of axial CT images disclosed the presence of bilateral LSC dysplasia (Figs. 1b, c). In order to relieve the hyperacusis and tinnitus, a bilateral myringotomy with ventilation tube insertion was carried out, after which the patient immediately noted relief from the tinnitus. However, the original condition returned a few months later, with bilateral fullness and intense hyperacusis.

Patient 3

A 47-year-old female presented with a five-year history of transitory pulsating left tinnitus without hearing loss or vestibular symptoms. She described a long episode of acute and intense hyperacusis after having flown in the past. Pure tone audiometry established normal hearing function in the absence of negative bone conduction thresholds bilaterally.

A C-AC-VEMPs study showed normal inner ear impedance (115 dB SPL threshold bilaterally). A bithermal caloric test was attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate it.

Temporal bone HRCT excluded inner ear malformations. However, a detailed axial CT study analysis carried out at our institution disclosed bilateral LSC dysplasia, in the absence of cochlear malformations. Moreover, the right high-riding jugular bulb showed slight dehiscence towards the vestibular aqueduct (Fig. 1d).

Discussion

Hyperacusis, especially in the case of somatosounds, is a typical finding of SSCD in association with a Tullio phenomenon and autophony 3. Over the past 10 years we have identified 176 cases of SSCD, of which about 48% of patients had hyperacusis together with their cochlear symptoms. As a result, every time a patient describes hyperacusis in his/her clinical history, we recommend a temporal bone HRCT completed with reformatted images along the superior and posterior semicircular canals planes to look for the presence of a "third mobile window", such as SSCD.

Apart from SSCD, to our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature describing other inner ear malformations that are responsible for hyperacusis. We have identified three cases of disabling hyperacusis in which radiologic exam excluded the presence of semicircular canal dehiscence (superior, posterior and lateral canals) and vestibular aqueduct enlargements, allowing the detection of bilateral dysplasia of the LSC canal and vestibule. As for patient 2, we actually identified a thinning of the cortical bone overlying the right superior semicircular canal, which could not be completely excluded as being responsible for both the long history of left posterior semicircular canal involvement by BPPV (positioning nystagmus very similar to SSCD) and the hyperacusis 4.

In the CT images of patient 3, we identified a small erosion of the right vestibular aqueduct by an enlarged jugular bulb, a condition which has been described to have features similar to SSCD, such as conductive hearing loss associated with normal C-AC-VEMPs 5. However, patient 3 had normal hearing function and a normal CAC- VEMPs threshold; therefore, the third window effect could be excluded.

In any case, the radiologist reported LSC malformation. Through a later T2-MR images analysis, we confirmed the LSC malformation in spite of any description by radiologists.

We therefore confirm, as has already been stated by other authors, that LSC dysplasia may be missed by simple visual inspection of radiologic images, especially if cochlear or vestibular aqueduct malformations, frequently associated findings, are absent 6. In the axial CT images, the LSC bony island diameter, the lumen of the anterior and the posterior arms and the vestibular shape should always be examined carefully 7. In cases of dilation both the anterior and the posterior arms, the LSC is called dysplasic (or hypoplasic) whereas, in cases of absent or rudimental LSC, it is called aplasic. However, the possibility of a partial malformation with dilation involving only one canal arm (anterior or posterior) has also been described; in these cases, the cochlea is normal while, in case of posterior arm dilation the vestibular aqueduct, is often enlarged 8 9. According to Sennaroglu and Saatci 10, LSC dysplasia is considered a minor dysmorphology belonging exclusively to vestibular labyrinthine malformations.

The results of several studies have not shown any consistent relationship between LSC bony island hypoplasia and hearing loss. Indeed, hearing function can be normal or impaired by pure sensorineural or pure conductive or mixed hearing loss 8-13, similar to the absence of a direct correlation between a large vestibular aqueduct and hearing loss 14. As for vestibular function, few reports have examined the vestibular symptoms of these patients, but similar to hearing function, no correlation between the severity of the canal and the vestibule malformations and vestibular impairing exists 15.

Nevertheless, no study in the literature has reported cases of hyperacusis associated with LSC aplasia and/or dysplasia. Concerning the pathophysiology of this condition, we hypothesized that the increased volume of inner ear liquid can modify the micromechanical function of the cochlea. The presence of LSC dysplasia is thought to allow largerthan- normal fluid motion, thereby producing an increased response in the basal turn of the cochlea, resulting in high frequency sound intolerance. Regarding this aspect, the study of otoacoustic emissions could be a useful tool to carry out a more in-depth analysis of cochlear function.

Moreover, the increased volume of the LSC could affect labyrinthine hydrodynamics and the driving force for the base-to-apex travelling wave along the basilar membrane, producing stationary waves capable of stimulating the neighbouring saccular receptors, which are responsive to low frequency stimuli 16, and are thus responsible for low frequency tone discomfort in patients. In our opinion, the use of HRCT segmentation images could be helpful in verifying the actual increase in vestibular liquid volume.

In the future, additional studies are required to follow the clinical evolution of patients, to complete the study of cochlear function with an otoacoustic emissions study, electrocochleography and, above all, to carry out HRCT segmentation images of the inner ear.

References

- 1.Katzenell U, Segal S. Hyperacusis: review and clinical guidelines. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:321–327. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baguley DM. Hyperacusis. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:582–585. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.12.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minor LB, Solomon D, Zinreich JS, et al. Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:249–258. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzari L. Multiple dehiscences of bony labyrinthine capsule. A rare case report and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010;30:317–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedmann DR, Le T, Pramanik BK, et al. Clinical spectrum of patients with erosion of the inner ear by jugular bulb abnormalities. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:365–372. doi: 10.1002/lary.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JL, Gittleman A, Barnes PD, et al. Utility of temporal bone computed tomographic measurements in the evaluation of inner ear malformations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:50–56. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan MY, Shiao JY, Ho CY, et al. Measurements of normal inner ear on computed tomography in children with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1361–1364. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J, Lalwani AK. Sensorineural and conductive hearing loss associated with lateral semicircular canal malformation. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1673–1679. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackler RK, Luxford WM, House WF. Congenital malformations of the inner ear: a classification based on embryogenesis. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:2–14. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540971301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. A new classification for cochleovestibular malformations. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2230–2241. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallan I, Berrettini S, Neri E, et al. Bilateral, isolated, lateral semicircular canal malformation without hearing loss. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:858–860. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell DD, Fischbein NJ, Patel A, et al. Two temporal bone computed tomography measurements increase recognition of malformations and predict sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1439–1446. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000229826.96593.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita K, Yoshiura T, Hiwatashi A, et al. Sensorineural hearing loss: there is no correlation with isolated dysplasia of the lateral semi-circular canal on temporal bone CT. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:229–233. doi: 10.1258/ar.2010.100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berrettini S, Forli F, Bogazzi F, et al. Large vestibular aqueduct syndrome: audiological, radiological, clinical, and genetic features. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walther LE, Nath V, Krombach GA, et al. Bilateral posterior semicircular canal aplasia and atypical paroxysmal positional vertigo: a case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:79–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd NP, Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG. Tuning and sensitivity of the human vestibular system to low-frequency vibration. Neurosci Lett. 2008;444:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]