Abstract

Efficient biomaterial screening platforms can test a wide range of extracellular environments that modulate vascular growth. Here, we used synthetic hydrogel arrays to probe the combined effects of Cys-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (CRGDS) cell adhesion peptide concentration, shear modulus and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) inhibition on human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis. HUVECs were encapsulated in degradable poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels with defined CRGDS concentration and shear modulus. VEGFR2 activity was modulated using the VEGFR2 inhibitor SU5416. We demonstrate that synergy exists between VEGFR2 activity and CRGDS ligand presentation in the context of maintaining HUVEC viability. However, excessive CRGDS disrupts this synergy. HUVEC proliferation significantly decreased with VEGFR2 inhibition and increased modulus, but did not vary monotonically with CRGDS concentration. Capillary-like structure (CLS) formation was highly modulated by CRGDS concentration and modulus, but was largely unaffected by VEGFR2 inhibition. We conclude that the characteristics of the ECM surrounding encapsulated HUVECs significantly influence cell viability, proliferation and CLS formation. Additionally, the ECM modulates the effects of VEGFR2 signaling, ranging from changing the effectiveness of synergistic interactions between integrins and VEGFR2 to determining whether VEGFR2 upregulates, downregulates or has no effect on proliferation and CLS formation.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Cell Encapsulation, ECM, Growth Factors, Hydrogel

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the growth of new vascular networks from existing blood vessels [1, 2], and controlling the growth of functional vasculature in biomaterials is critical to developing functional tissue constructs. Perhaps the most well-studied mediator of angiogenesis is Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which activates signaling cascades through VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) that promote endothelial cell proliferation [3, 4] and survival [5]. When presented as a concentration gradient, VEGF directionally guides the formation of new vasculature through cell migration and tubule formation [1, 6]. An additional controller of cell viability [7-9], migration [10], proliferation [11] and tubulogenesis [12] is the extracellular matrix (ECM), but there is currently a limited understanding of how the ECM and VEGFR2 activity jointly modulate angiogenesis. Understanding how the extracellular matrix modulates VEGF-driven vascular growth is critical to understanding healing and developmental processes as well as evaluating the effectiveness of drugs designed to modulate angiogenesis.

Though the role of ECM in modulating VEGFR2 activity is not fully understood, there is evidence that VEGFR2 activity is influenced by integrin binding and extracellular matrix rigidity. Binding of α5β1 as well as αvβ3 integrins to extracellular matrix proteins such as fibronectin and collagen elevates VEGF and VEGFR-2 activity in endothelial cells [13-16], and RhoA and ROCK phosphorylation increase VEGFR2 activity in endothelial cells that exist in stiffer environments [17, 18]. With these findings, it is reasonable to hypothesize that unusual extracellular environments such as growing tumors can lead to aberrant vascular growth. Tumor-associated endothelial cells have been shown to overexpress integrins relative to endothelial cells in normal tissue [19], and the ECM in cancerous breast tissue is stiffer than ECM in healthy breast tissue due to increased protein deposition [20-22]. These effects are likely to result in differing VEGFR2 activity between wound healing sites, developing tissues or tumors. Detailed studies of cell-ECM interactions during angiogenesis can be conducted via in-vitro experimentation, but so far most studies of in-vitro angiogenesis have limited control over extracellular environments due to the use of naturally-derived materials as matrices. Additionally, in-vitro studies of angiogenesis are usually performed using low throughput experimentation techniques. These experimental formats result in a limited ability to control specific ECM properties and attribute specific, combinatorial modifications to the ECM directly to changes in cell behavior.

Much of what is known about cell-ECM interactions has been discovered in two-dimensional (2D) environments where surfaces can be made to present extracellular matrix proteins, cell adhesion molecules and growth factors. Common examples include protein-coated polymers [23], self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) [3, 11, 24, 25], patterned microwells [26, 27] and hydrogel surfaces [28-30]. While these substrates enable rapid analysis of cell interactions with specific ECM components, they do not approximate the three-dimensional (3D) extracellular environments that exist in vivo. Many important differences in cell behavior exist between 2D and 3D environments. For example, the expression of ECM-degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) is not required in the formation of capillary networks on surfaces, whereas MMP expression is critical for capillary growth in 3D matrices that restrict cell movement [31-34]. Matrix stiffness and cell adhesion ligand concentration affect endothelial cell migration [10, 35, 36] and network branching [37] differently in 2D and 3D environments. Additionally, it is well accepted that endothelial cells in 2D culture are directly exposed to soluble growth factors [3, 38] whereas growth factor and oxygen diffusion into hydrogels [39-41] play a role in spatially guiding vascularization in 3D environments. These previous studies emphasize not only the importance of 3D environments, but also the variety of parameters that can influence 3D capillary formation.

In order to culture endothelial cells in a variety of 3D environments, as well as investigate the specific effects of VEGF signaling in well-defined settings, we have developed an enhanced-throughput array format capable of 3D cell culture in poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels. PEG is a hydrophilic polymer that resists non-specific protein adsorption [42]. The use of this non-fouling material as the backbone of a hydrogel enables the investigation of how specific modifications to an otherwise “blank slate” extracellular microenvironment affect cell behavior. When multi-arm PEG molecules are functionalized with norbornene groups, the PEG can be controllably decorated with biomimetic signaling peptides and crosslinked into hydrogels through thiol-alkene (thiol-ene) coupling [43, 44]. Previously, screening formats have been utilized to investigate cell-ECM interactions in 2D environments. Examples include micropatterned hydrogel spots on silicon and glass [45], SAM arrays [3, 11, 24] and 24 well plates presenting self-assembling peptide hydrogels [30]. Screening platforms for investigating cell-ECM interactions in 3D environments have included microliter-scale hydrogels in 96 or 48 well plates, cell clusters cultured in isolation by photomasking [46, 47] and PEG-diacrylate hydrogel arrays [7-9]. While these screening platforms enable cell culture in fully 3D, customizable environments, they often consume large amounts of material, require specialized equipment and a high degree of technical proficiency to utilize, and place hydrogels in confined environments unable to support homogeneous swelling. The array developed here consists of 1mm diameter, 200 μm thick spots protruding from a single hydrogel background. Thus, each hydrogel array spot was allowed to swell uniformly in an unconfined manner by virtue of their connection to a hydrogel base that was also allowed to swell (i.e. the hydrogel spots were neither confined nor linked to a rigid support).

Here we used an array of PEG hydrogels to screen the combined effects of adhesion ligand density, modulus and VEGFR2 signaling on pro-angiogenic cell behaviors using encapsulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) as a model cell type. We hypothesized that cell adhesion, hydrogel modulus and VEGFR2-mediated signaling would synergistically modulate viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis of HUVECs. We also hypothesized that a VEGFR2 inhibitor modulates viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis differently depending on surrounding ECM contexts and therefore compared the effects of the inhibitor in our PEG hydrogels to effects in Matrigel, a standard platform for screening angiogenesis drugs in vitro [48].

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured in medium 199 (M199) (Mediatech Inc, Manassas, VA) supplemented with EGM-2 Bulletkit (Lonza). The medium supplement contained 2% bovine serum albumin as well as hydrocortisone, hFGF-B, VEGF, R3-IGF-1, Ascorbic Acid, Heparin, FBS, hEGF, and GA-1000. For simplicity M199 supplemented with EGM-2 will be referred to as “growth medium.” Growth medium was changed every other day and cells were passaged every 4 to 5 days. Cell passages were performed using 0.05% trypsin solution (HyClone, Logan, UT) and detached cells were recovered in M199 supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (HyClone). All media was supplemented with 100 U/mL Penicillin/100 μg/mL Streptomycin (HyClone). The cells were maintained in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 and used between 7 and 16 population doublings in all experiments.

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) functionalization with norbornene

PEG-norbornene (PEGNB) was synthesized as previously described, with minor modifications during purification [43, 49]. Briefly, solid 8-arm PEG-OH (20 kDa molecular weight, tripentaerythritol core, Jenkem USA, Allen TX), dimethylaminopyridine and pyridine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). In a separate reaction vessel, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and norbornene carboxylic acid (Sigma Aldrich) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane. Norbornene carboxylic acid was covalently coupled to the PEG-OH through the carboxyl group by combining the PEG solution and norbornene solutions and stirring the reaction mixture overnight under anhydrous conditions. Urea was removed from the reaction mixture using a glass fritted funnel and the filtrate was precipitated in cold diethyl ether (Fisher). The precipitated PEGNB was collected and dried overnight in a buchner funnel. To remove impurities, the PEGNB was dissolved in chloroform (Sigma Aldrich), precipitated in diethyl ether and dried a second time in a Buchner funnel. To remove excess norbornene carboxylic acid, PEGNB was dissolved in de-ionized H2O, dialyzed in de-ionized H2O for 1 week and filtered through a 0.4 μm pore-size syringe filter. The aqueous PEGNB solution was frozen using liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. Functionalization of PEG with norbornene groups (Fig. 1A) was quantified using proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) to detect protons of the norbornene-associated alkene groups located at 6.8-7.2 PPM [43]. Functionalization efficiency for norbornene coupling to PEG-OH arms was above 88% for all PEGNB used in these experiments.

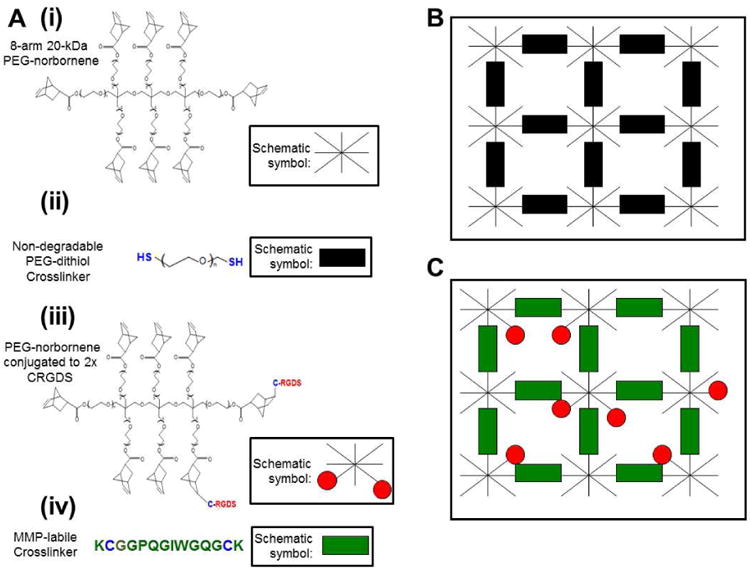

Figure 1.

Molecules included in PEG hydrogels. A) The hydrogels are composed of (i) 8-arm PEG molecules, with each arm functionalized with a norbornene molecule; (ii) Di-thiolated PEG crosslinking molecules bridge multiple 8-arm PEG molecules together into an ordered polymer network. A di-thiolated PEG molecule acts as an inert crosslinking molecule that is not cell-degradable; (iii) In bioactive hydrogels, PEG molecules are decorated with CRGDS adhesion peptide or CRDGS scrambled peptide to modulate cell adhesion to the hydrogel; (iv) Di-thiolated matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) labile crosslinking peptides enable cell-driven hydrogel degradation. B) “Background” hydrogels are void of cell adhesion molecules and are not subject to cell-driven degradation. C) “Hydrogel spots” modulate cell behavior through covalently attached adhesion molecules and are biodegradable via MMP activity.

Pre-coupling adhesion peptides to PEGNB

Lyophilized PEGNB was dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (1× PBS) at 10 mM concentration (80 mM norbornene groups) and combined with 0.05% w/v Irgacure 2959 photoinitiator (I2959) (Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Tarrytown, NY) as well as 2× molar excess of either amidated Cys-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (CRGDS) adhesion peptide or amidated Cys-Arg-Asp-Gly-Ser (CRDGS), a scrambled nonfunctional peptide (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ). The mixture was reacted under 365 nm UV light for 3 minutes at a dose rate of 4.5 mW/cm2 to covalently attach the peptides to norbornene groups (Fig. 1A) via the thiol-ene reaction [43]. To remove buffer salts and unreacted peptide from the decorated PEGNB, the reaction mixture was dialyzed in de-ionized H2O for 2 days. The dialyzed solution was frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. The coupling efficiency of PEGNB to the peptides was quantified using proton NMR to detect disappearances of alkene protons at 6.8-7.2 PPM caused by covalent bonding of the peptides to the norbornene group. For simplicity, pre-coupled PEGNB molecules will be referenced as PEGNB-CRGDS and PEGNB-CRDGS.

Forming PEG hydrogels

Hydrogel array constructs were formed from 2 separate hydrogels: the inert hydrogel “background” (Fig. 1B) that is crosslinked using 3.4 kDa PEG-dithiol (PEGDT) (Fig. 1A) crosslinking molecule (Laysan Bio, Arab, AL), and “hydrogel spots” (Fig. 1C) that are decorated with adhesion peptides and crosslinked using MMP-degradable KCGGPQGIWGQGCK peptide (Fig. 1A) (Genscript) [50]. All hydrogel solutions were created in serum-free M199 and consisted of PEGNB, 0.05% w/v I2959 and 2× molar excess crosslinking molecule to PEGNB to achieve 50% crosslinking density (Fig. 1). To vary cell adhesion to the hydrogels, precoupled-PEGNB-CRGDS and PEGNB-CRDGS molecules were added to the solutions to achieve desired adhesion peptide concentration with a total of 2 mM pendant peptide included in every solution. To vary the modulus of the background hydrogels the combined percent weight of PEGNB and PEGDT was varied between 4, 6 or 8% w/v. To vary the modulus of the hydrogel spots, the combined percent weight of the PEGNB, degradable crosslinking molecule and adhesion peptides was varied between 4.2, 5 and 7% w/v.

Mechanical properties of PEG hydrogels

Mass equilibrium swelling ratios and shear modulus were measured in background hydrogel samples and bulk samples of hydrogel spots. To measure mass equilibrium swelling ratios (Q), 20 μL droplets of hydrogel solutions were pipetted onto a flat Teflon surface and crosslinked under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2. The samples were swelled in serum-free M199 for 24 hours and weighed for swollen weight (WS). Afterward, the samples were washed in de-ionized H2O overnight to remove M199 components from the hydrogel, frozen in -80°C for 2 hours and lyophilized. The dried polymer was weighed for dry weight (WD) and mass equilibrium swelling ratio was calculated as per equation 1.

Equation 1: Mass equilibrium swelling ratio

To measure the shear modulus of the hydrogels, 660 μL of the above solutions were pipetted into 2.1cm diameter Teflon wells. The resulting hydrogels were swollen in 1× PBS for 24 hours before test samples of 8 mm diameter were retrieved using a hole punch with 3 replicates per condition. The samples were tested using an Ares-LS2 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). A 20 g force was applied to the samples and a strain sweep test at 10 Hz fixed frequency was performed from 0.1 to 20% strain. Complex shear modulus of each sample was as the average of measurements taken at 10 Hz, 1-10% strain.

Hydrogel array stencils

Hydrogel array stencils were fabricated using conventional photolithography techniques [51] and were formed from two separate elastomer parts: a 200 μm thick sheet of microwells and a 1mm thick base. Briefly, silicon master molds were fabricated by spin coating a 200 μm layer of SU-8 100 (Microchem, Newton, MA) onto a silicon wafer (University Wafer, Boston MA). Arrayed 1 mm diameter posts of photoresist were defined using a photomask (Imagesetter, Madison, WI). Poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS) was prepared by combining Sylgard PDMS solution with crosslinking solution (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) at a 10:1 volume ratio. The solution was degassed under a vacuum for 45 minutes, poured onto the silicon master mold and crosslinked on a hot plate for 4 hours at 85°C, forming the 200 μm thick sheet of microwells that penetrated the entire thickness of the sheet. To form the base of the hydrogel array stencil, the PDMS solution was poured between glass slides to form sheets of 1 mm thickness and cured on a hot plate for 4 hours at 85°C. Both stencil components were cleaned in hexanes (Fisher) by soxhlet extraction [52] and placed in vacuo to remove residual solvent. The completed PDMS stencil was formed by laying the 200 μm thick sheet on top of the 1 mm thick base.

Forming PEG hydrogel arrays

Hydrogel spot solutions were added to the PDMS stencil wells as 0.4 μL droplets (Fig. 2). To solidify the hydrogel spots before dessication, the droplets were crosslinked under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2 after every 5 droplets were patterned. A photomask was used to prevent multiple UV exposures to previously cured spots.

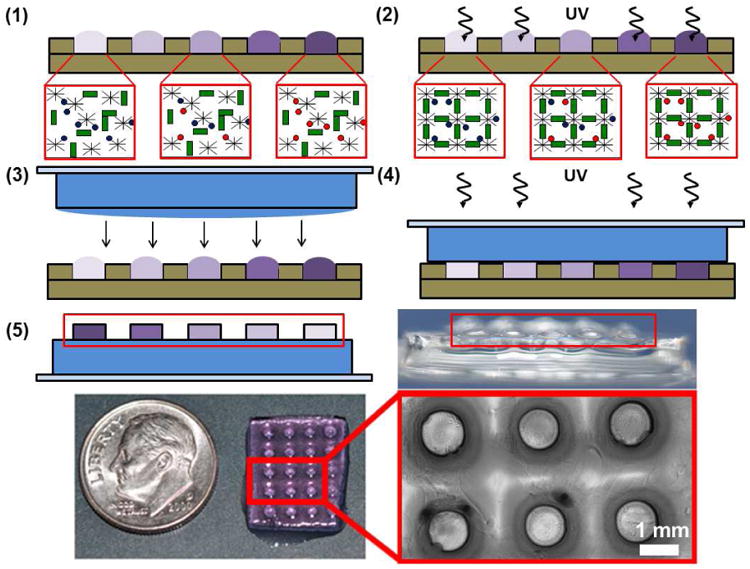

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of hydrogel array fabrication. 1) Separate hydrogel spot solutions containing various ratios of CRGDS adhesion peptide (Red circles) and a scrambled CRDGS non-functional peptide (Blue circles) are pipetted into wells of a PDMS stencil. Total pendant peptide concentration is fixed at 2 mM in all solutions. 2) The hydrogel spots are crosslinked in the stencil using UV light. 3) A crosslinked 1-mm thick “background” hydrogel slab is laid on top of the crosslinked bioactive hydrogel spots. A thin layer of background hydrogel solution is added to the slab to anchor the cured spots to the background. 4) The hydrogel spots are anchored to the background after treatment with UV light. 5) The completed hydrogel array is removed from the stencil. Red boxes highlight the raised spots in the schematic and side view images of the arrays.

Once all spots were crosslinked under UV light, a 1 mm-thick background hydrogel slab was formed by curing 230 μL background hydrogel solution under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2 between a flat 1 mm thick PDMS sheet and a 1″ × 1″ glass slide. After removing the PDMS sheet only, an additional 30 μL background hydrogel solution was pipetted on top of the hydrogel slab to anchor the spots to the background slab upon crosslinking. The background slab, still attached to the glass slide, was placed on top of the cured hydrogel spots and the entire array was cured for an additional 2 seconds under 365 nm UV light at a 90 mW/cm2 dose rate. The hydrogel array was removed from the PDMS stencil and submerged in medium in a 6-well cell culture plate. The completed arrays were secured to the bottom of the wells by using magnets to hold the glass slides in place.

Peptide incorporation into hydrogel array spots

To verify controllable peptide incorporation into the hydrogel array spots, hydrogel solutions of 12% w/v total polymer consisting of PEGNB, a 2× molar excess of 3.4 kDa PEG dithiol to PEGNB, and PEGNB-CRGDS such that 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 2 mM concentrations of CRGDS were patterned into the array using the above procedure. The background hydrogels were compositionally identical to the spots but were lacking CRGDS. CRGDS concentration was verified by labeling the N-terminus of the peptide with fluorescein. Briefly, the arrays were treated with 3 μM solution of f1luorescein-conjugated sulfodichlorophenol ester (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) in PBS, incubated for overnight, then rinsed for 24 hours in new PBS. The fluorescently labeled spots were photographed using a Nikon TI Eclipse microscope, and fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software.

HUVEC viability, tubulogenesis and proliferation in 3D hydrogel arrays

During hydrogel array fabrication, hydrogel spots contained HUVECs at a density of 2 × 107 cells/mL. The concentration of CRGDS adhesion peptide was adjusted to 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM through the addition of PEGNB-CRGDS, with the total pendant peptide concentration in all hydrogel spots maintained at 2 mM by adding PEGNB-CRDGS. Total polymer percent weight was varied between 4.2, 5 and 7% w/v in the hydrogel spots and 4, 6 and 8% w/v in the backgrounds, with low percent weight hydrogel spots corresponding to low weight percent backgrounds and high percent weight hydrogel spots corresponding to high percent weight backgrounds. During viability experiments, arrays of encapsulated cells were cultured for 48 hours in growth medium alone or with 10 μM SU5416 (Sigma Aldrich), a known inhibitor of VEGFR2 signaling [53]. Medium was replaced 24 hours after encapsulation. After 48 hours of culture, the arrays were washed with serum-free M199 and stained with 5 μM Cell Tracker Green (Invitrogen) for 45 minutes in M199. After 15 minutes of staining, the staining solution was supplemented with Hoescht nuclear stain (Invitrogen) to achieve a final concentration of 10 μg/mL. After staining, the arrays were washed with serum-free M199 and incubated for 30 minutes in growth medium containing 2 μM ethidium homodimer (Invitrogen). The arrays were then washed with 1× PBS and fixed for 30 minutes in 10% buffered formalin (Fisher). The arrays were soaked in 1× PBS overnight and photographed using a Nikon TE300 fluorescence microscope within 48 hours of fixation. Viability was quantified by dividing the number of live cell nuclei by total nuclei in the post.

During proliferation and tubulogenesis experiments, the arrays of encapsulated cells were cultured in growth medium alone or with 10 μM SU5416 for 24 hours only. Afterward, the cells were incubated for 5 hours in growth medium with 20 μM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) (Invitrogen) as a proliferation marker and, if appropriate, 10 μM SU5416. Afterward, the arrays were stained with Cell Tracker Green in the same manner as the viability assay, but without Hoescht nuclear stain or ethidium homodimer. The arrays were washed with 1× PBS, fixed for 30 minutes in 10% buffered formalin and stained using the Click-iT EdU 594 proliferation kit (Invitrogen). The staining procedure was slightly modified from the manufacturer's instructions, as Alexa Fluor® 594 was diluted to half the recommended concentration. The arrays were soaked in 1× PBS overnight and photographed using a Nikon TE300 fluorescence microscope. Proliferation was quantified by counting the number of EdU-positive cells and dividing by the total number of nuclei in the post. Tubulogenesis was quantified by manually measuring total capillary-like structure (CLS) length in each post as labeled by Cell Tracker Green. To obtain confocal microscopy images, the hydrogel arrays were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade solution (Invitrogen) and photographed on a Nikon A1R-Si confocal microscope.

HUVEC proliferation with VEGFR2 inhibition

HUVECs were plated in tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) 24-well plates at a density of 5.0 × 104 cells/cm2. The cells were grown in growth medium alone or with 10 μM SU5416 for 24 hours. Afterward, the medium was changed to fresh growth medium with or without 10 μM SU5416 and 20 μM EdU. After 5 hours of incubation, the cells were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 30 minutes and stained using the Click-iT EdU 488 proliferation kit (Invitrogen). The staining procedure was slightly modified from the manufacturer's instructions, as Alexa Fluor® 488 was diluted to half the recommended concentration. The cells were photographed using a Nikon TE300 fluorescence microscope and proliferation was quantified via by counting nuclei staining positive for EdU and normalizing the number to total nuclei.

HUVEC tubulogenesis in Matrigel

HUVECs were suspended in growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at a density of 2 × 107 cells/mL. A 200 μm thick PDMS sheet of microwells was placed on top of a glass slide and the Matrigel-cell suspension was pipetted as 0.4 μL droplets into the microwells. These arrays of Matrigel “spots” were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and covered in growth medium alone or with 10 μM SU5416. After 48 hours of culture, the arrays were stained with Cell Tracker Green in the same manner as in the PEG hydrogel viability assay, but without Hoescht nuclear stain or ethidium homodimer. The arrays were washed with 1× PBS and fixed for 30 minutes in 10% buffered formalin. A green fluorescence and phase contrast z-stack image of each spot was taken at 48 hours after encapsulation using a Nikon TI Eclipse microscope. Total CLS length in each individual spot was quantified manually.

HUVEC tubulogenesis in confined hydrogels

HUVEC tubulogenesis in 10 μL volume hydrogels was qualitatively assessed to determine the effects of hydrogel confinement on CLS formation. Here, the hydrogels contained 4.2% w/v total polymer, a 2× molar excess of cell-degradable crosslinking peptide to PEGNB, and PEGNB-CRGDS to establish a CRGDS concentration of 2 mM. The HUVECs used in these hydrogels were treated with 1 μM Cell Tracker Green prior to trypsinization. Briefly, the cells were washed with serum-free M199 and stained with Cell Tracker Green for 45 minutes in M199. After staining, the cells were washed with serum-free M199 and incubated for 30 minutes in growth medium. After trypsinization, the cells were resuspended in the PEG hydrogel solution at a density of at 2 × 107 cells/mL.

To observe tubulogenesis in confined hydrogels, the cell-containing hydrogel solutions were pipetted as 10 μL droplets on the bottoms of 48-well TCPS plates. The droplets were crosslinked under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2. To ensure that the droplets remained stationary throughout the duration of the experiment, 90 μL of 8% w/v background hydrogel solution was added around the solidified hydrogels and crosslinked under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2. The encapsulated cells were incubated in growth medium with 10 μM SU5416 for 24 hours. A green fluorescence and phase contrast z-stack image of each sample was taken using a Nikon TI Eclipse microscope 24 hours after encapsulation.

To observe tubulogenesis in unconfined hydrogels, the cell-containing hydrogel solutions were pipetted as 10 μL droplets on a flat PDMS sheet and crosslinked under 365 nm UV light for 2 seconds at a dose rate of 90 mW/cm2. The resulting hydrogels were transferred to a 24-well TCPS plate containing growth medium with 10 μM SU5416. After 24 hours of incubation, the gels were pinned using a 24-well culture inserts (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to keep them stationary during photography. A green fluorescence and phase contrast z-stack image of each sample was taken using a Nikon TI Eclipse microscope 24 hours after encapsulation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences were calculated using the two-sided Student's T-test assuming equal variances. Statistical significance was denoted as p < 0.05.

Results

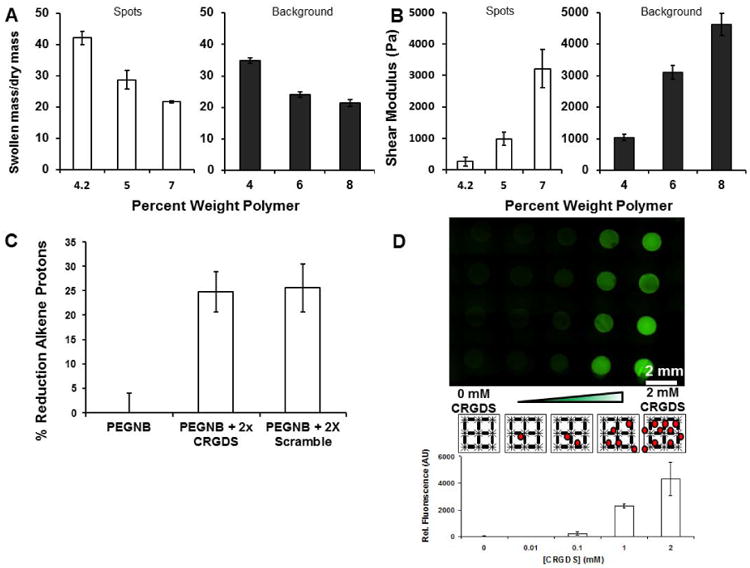

Hydrogel equilibrium swelling ratio and complex shear modulus

The swelling properties and moduli of degradable hydrogel spots and inert background hydrogels were controlled by adjusting the percent weight of polymer included in the formulations. Hydrogel spot formulations containing 4.2, 5 and 7% w/v polymer had mass equilibrium swelling ratios of 42.1 ± 2.1, 28.7 ± 2.9, and 21.6 ± 0.4, respectively. Background hydrogels containing 4, 6 and 8% w/v polymer had equilibrium swelling ratios of 34.9 ± 0.9, 23.9 ± 0.9 and 21.3 ± 1.1, respectively (Fig. 3A). The background hydrogels were designed to have similar but slightly lower swelling ratios than the hydrogel spots in order to provide a more stable substrate for anchoring the spots during culture. Hydrogel spot formulations containing 4.2, 5 and 7% w/v polymer had moduli of 260 ± 140 Pa, 980 ± 210 Pa and 3220 ± 610 Pa, respectively. Therefore, the 4.2, 5 and 7% w/v hydrogels were designated as “low”, “medium” and “high” modulus hydrogels for the duration of the study to clarify the presentation of the data. The moduli of the 4, 6 and 8% w/v background hydrogels were 1040 ± 100 Pa, 3100 ± 220 Pa and 4160 ± 350 Pa, respectively (Fig. 3B). The range of moduli chosen for this study (∼260-3220 Pa) spans a wide range of tissues, including soft tissues such as the vocal fold lamina [54], as well as normal breast tissue and cancerous breast tissue, two examples of tissues that differ in mechanical properties as well as extent of vascularization [55, 56].

Figure 3.

Characterizing mechanical properties and pendant peptide incorporation into the hydrogel array. A) Equilibrium swelling ratios of degradable (left) and background (right) and hydrogels used in low, medium and high hydrogel modulus conditions. B) Complex shear modulus of degradable (left) and background (right) hydrogels using in low, medium and high hydrogel modulus conditions. Error bars indicate standard deviation. C) Reduction in norbornene alkene protons due to covalent coupling of CRGDS and CRDGS as measured using NMR. D) N-terminal amines of CRGDS were labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488 (Green). Green fluorescence intensity was quantified from the left to right columns (Black lines: PEG polymer and crosslinker. Red circles: CRGDS).

Hydrogel array fabrication and peptide incorporation

The hydrogel constructs in this study consisted of arrayed PEG hydrogel spots that contained controlled concentrations of CRGDS. Functionalization efficiency of PEGNB with CRGDS or CRDGS was confirmed using NMR. The adhesion peptides CRGDS and CRDGS were reacted to PEGNB at 2× molar excess to decorate, on average, two of the eight arms of the PEGNB molecule with the cell adhesion peptides. The presence of CRGDS at 2× molar excess to PEGNB resulted in a 24.8 ± 4.1% reduction of alkene protons present on the PEG molecule, and the presence of CRDGS at 2× molar excess to PEGNB resulted in a 25.7 ± 4.9% reduction of alkene protons (Fig. 3C). This indicates that approximately 2 of the 8 available norbornene groups on a given PEGNB molecule were coupled to the adhesion peptide, as expected.

Incorporation of peptide-decorated PEG macromers into the hydrogel arrays was also visualized using fluorescein staining via a sulfodichlorophenol-ester linkage. Fluorescent signals from the array were directly proportional to the amount of peptide added to the arrayed hydrogel spots. Additionally, only background fluorescence was detected between the spots, indicating that the peptides were present in the spots only (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that PEG hydrogels can be used to provide synthetic control over incorporation of thiol-containing ligands, in this case, the cell adhesion peptide CRGDS.

Three-dimensional cell viability in PEG hydrogel arrays

We quantified viability of encapsulated HUVECs to verify that the cells withstood the encapsulation and array patterning processes, and to evaluate the effects of adhesion ligand density and stiffness on maintaining cell survival. Cell viability generally increased with increasing CRGDS, and high modulus conditions suppressed viability. In all conditions HUVECs displayed viability levels at or above 40% of total encapsulated cells, with the lowest viability levels observed in spots containing 0 mM CRGDS. Increased CRGDS concentration increased viability in all modulus conditions, with maximal viability observed at 0.5 and 1.0 mM CRGDS. At these optimal CRGDS concentrations, low modulus hydrogels promoted the highest viability levels compared to equivalent CRGDS concentrations in higher modulus conditions. However, viability in the low and medium modulus hydrogels decreased when CRGDS concentration was increased from 1.0 to 2.0 mM. This decrease did not reduce viability below levels observed at 0 mM CRGDS concentrations, indicating that the 2.0 mM CRGDS concentration was suboptimal, but not detrimental to HUVEC viability relative to non-adhesive conditions. In the high modulus condition, there was no significant decrease in HUVEC viability at 2.0 mM when compared to 1.0 mM CRGDS, suggesting a role of stiffness in maintaining viability in the presence of high CRGDS concentrations (Fig. 4A).

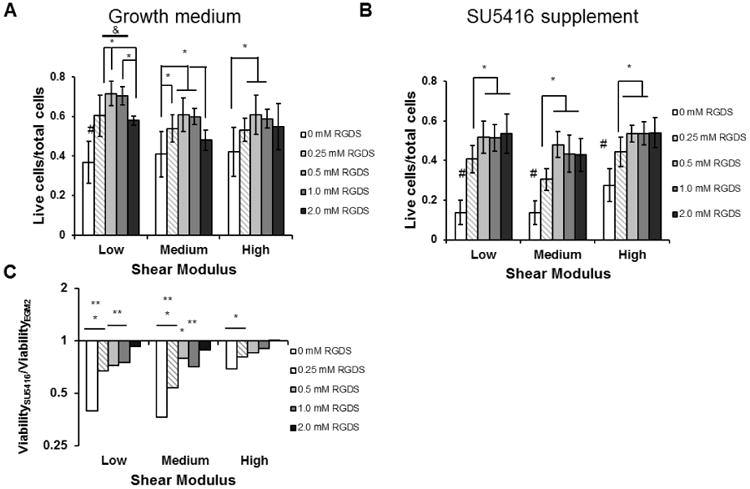

Figure 4.

Viability of HUVECs encapsulated inside the hydrogel array spots. A) Cell viability as determined by counting live cell and dead cell nuclei 48 hours after encapsulation. B) Cell viability measured when VEGFR2 was inhibited by 10 μM SU5416 supplementation. *, p < 0.05. &, p < 0.05 compared to all equivalent CRGDS concentration in other modulus conditions C) Viability of SU5416-treated HUVECs normalized to HUVEC viability in growth medium. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared to growth medium control.

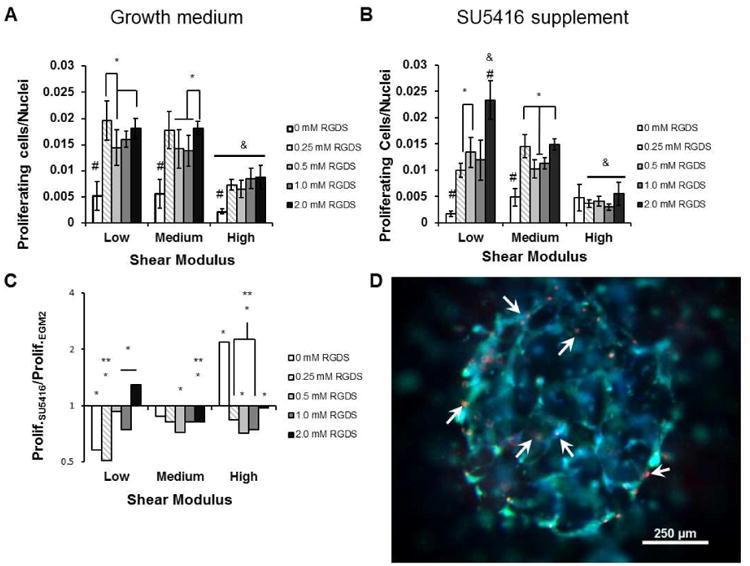

Three-dimensional cell proliferation in PEG hydrogel arrays

The effects of cell adhesion and stiffness on proliferation were determined by labeling and quantifying the nuclei of encapsulated HUVECs in S-phase. In all modulus conditions, the addition of CRGDS to the hydrogel increased cell proliferation beyond spots lacking CRGDS (Fig. 5A). Proliferation did not follow a monotonic trend with increasing CRGDS, and high modulus hydrogels suppressed proliferation relative to low and medium modulus conditions. In particular, proliferation in the low and medium modulus conditions displayed a biphasic response to increasing CRGDS. Proliferation was lower at 0.5 mM CRGDS compared to 0.25 and 2.0 mM CRGDS in the low modulus condition and lower at both 0.5 and 1.0 mM CRGDS compared to 2.0 mM CRGDS in the medium modulus condition. In the high modulus condition, the overall proliferation rate was significantly lower than proliferation rates in the low and medium modulus conditions, and no significant differences in proliferation existed between any conditions containing CRGDS. In addition to ECM effects on proliferation, we also qualitatively noted that a majority of proliferating cells co-localized with multicellular structures (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Proliferation of HUVECs encapsulated inside the hydrogel array spots. A) Cell proliferation as determined by Click-it EdU staining 24 hours after encapsulation B) Cell proliferation measured when VEGFR2 was inhibited by 10 μM SU5416 supplementation. *, p < 0.05. &, p < 0.05 compared to all equivalent CRGDS concentration in other modulus conditions C) Cell proliferation during SU5416 treatment normalized to proliferation in growth medium. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared to growth medium control. D) Proliferating cells (arrowheads) were localized to multicellular structures. Green: Cell Tracker Green. Blue: Hoescht nuclear stain. Red: Alexa Fluor® 594 labeling nuclei of cells in S-phase.

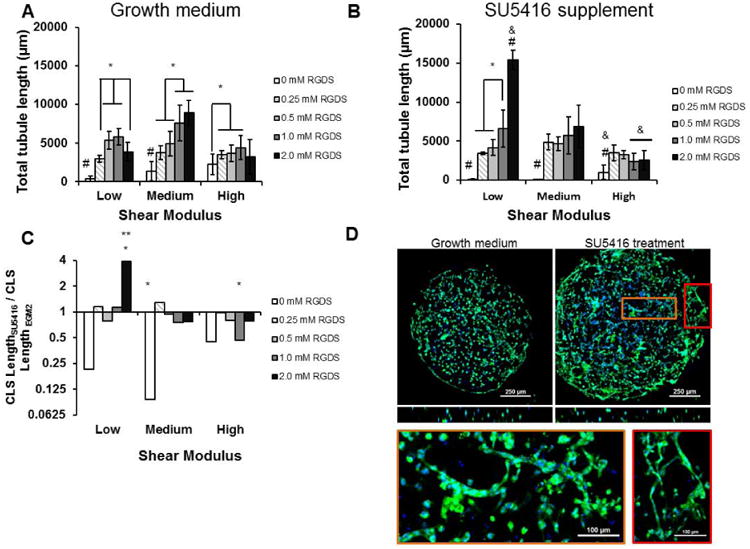

Three-dimensional tubulogenesis in PEG hydrogel arrays

Cell adhesion and hydrogel stiffness significantly influenced total capillary-like structure (CLS) length in the hydrogel spots, and optimal levels of CRGDS concentration and modulus maximized CLS formation in the range of conditions tested. In all modulus conditions, CLS formation was rare in the absence of CRGDS. In the low modulus condition, CLS formation increased with increasing CRGDS up to 1.0 mM concentration and decreased at 2.0 mM CRGDS. This trend was not observed in the medium modulus condition where CLS formation remained elevated at 2.0 mM CRGDS (Fig. 6A). In the high modulus condition CLS formation was significantly increased at 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mM CRGDS compared to the condition lacking CRGDS, but this increase was no longer significant at 2.0 mM CRGDS. CLS formation at 0.5 mM CRGDS was significantly lower in the high modulus condition compared the low modulus condition and CLS formation at 1.0 and 2.0 mM CRGDS was lower in the high modulus condition compared to the medium modulus condition, indicating that high stiffness interfered with CLS formation in these hydrogels. Taken together, these results suggest that tubulogenesis increases with increasing CRGDS, but the most significant increases were observed in an optimal, medium modulus condition that was not excessively compliant or stiff.

Figure 6.

Tubulogenesis of HUVECs encapsulated inside the hydrogel array spots. A) Total tubule length was determined by manually measuring tubule lengths throughout the spots from epifluorescence Z-stack images. The cells were stained using Cell Tracker Green and Hoescht nuclear stain 24 hours after encapsulation. B) Tubulogenesis when VEGFR2 was inhibited by 10 μM SU5416 supplementation. *, p < 0.05. &, p < 0.05 compared to all equivalent CRGDS concentration in other modulus conditions C) Tubulogenesis during SU5416 treatment normalized to tubulogenesis in growth medium. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared to growth medium. D) Confocal microscopy images of low tubulogenesis in low modulus, 2 mM RGDS spots and increased tubulogenesis levels with SU5416 treatment. Bottom: Enlarged examples of capillary-like structures seen in the VEGFR2-inhibited condition. Scale bars: 100 μm. Green: Cell Tracker Green. Blue: Hoescht nuclear stain.

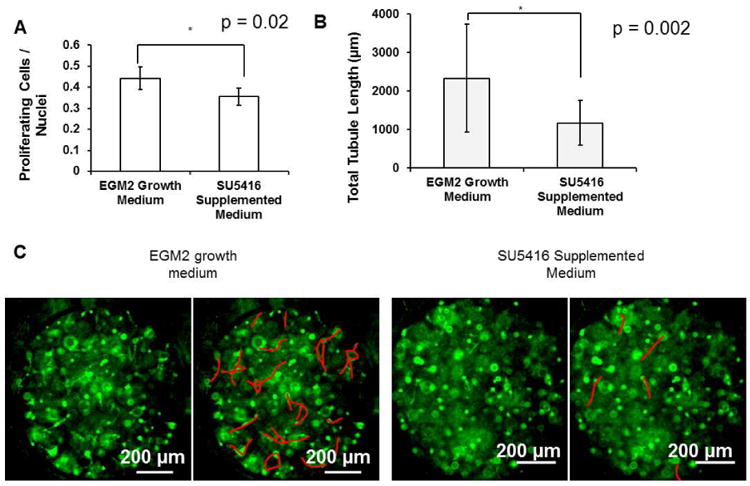

HUVEC viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis with VEGFR2 inhibition

SU5416 is an inhibitor to VEGFR2 phosphorylation [53], and we confirmed that inhibiting VEGF signaling by adding SU5416 to growth medium reduced HUVEC proliferation and tubulogenesis in traditional cell culture systems in our hands. When HUVECs were seeded on TCPS surfaces and assayed for proliferation, VEGFR2 inhibition resulted in a 20% decrease in proliferation compared to the growth medium control (Fig. 7A). When HUVECs were encapsulated in growth factor-reduced Matrigel and assayed for CLS formation, VEGFR2 inhibition resulted in a 50% decrease in total tubule length compared to HUVECs incubated with growth medium only (Fig. 7B,C).

Figure 7.

Effects of VEGFR2 inhibition in standard model systems. A) HUVEC proliferation with and without SU5416 supplementation on tissue culture-treated polystyrene (TCPS). *, p < 0.05. B) HUVEC tubulogenesis with and without SU5416 supplementation in growth factor-reduced Matrigel. C) HUVEC CLS formation in 0.4 μL Matrigel spots. In each pair of pictures, the tubules in the right hand copy were highlighted. Green: Cell Tracker Green. *, p < 0.05 between EGM2 and SU5416-treated conditions.

To explore the combinatorial roles of VEGFR2 signaling, controlled adhesion ligand density and stiffness in synthetic environments, we encapsulated HUVECs in hydrogel array spots, inhibited VEGFR2 signaling and assayed for viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis. VEGFR2 inhibition significantly reduced cell viability in conditions that did not contain the CRGDS cell adhesion peptide (Fig. 4B). In all modulus conditions viability plateaued at 0.5 mM CRGDS, indicating a limited role of CRGDS in maintaining cell viability when VEGFR2 was inhibited. This also suggests a synergistic interaction between VEGFR2 and integrin-mediated cell adhesion in the context of HUVEC viability. However, while normal VEGFR2 generally increased viability levels when compared to inhibited VEGFR2, the difference between normal VEGFR2 conditions and inhibited conditions decreased as the CRGDS concentration increased. In all modulus conditions, the reduction of viability with VEGFR2 inhibition was insignificant in spots containing 2 mM CRGDS, indicating a diminishing role of VEGFR2 in modulating viability in the presence of increased CRGDS. Additionally, the effect of VEGFR2 inhibition on viability was not significant in the high modulus condition when CRGDS concentration was at or above 0.5 mM CRGDS (Fig. 4C), indicating that the role of VEGFR2 was not as substantial in high modulus compared to lower modulus hydrogels. These results indicated that synergy possibly exists between VEGFR2 and integrin binding, but that the role of VEGFR2 was modulated by CRGDS levels and stiffness. In essence, the importance of VEGF signaling during 3D HUVEC culture was context-dependent.

HUVEC proliferation was decreased by VEGFR2 inhibition in a majority of hydrogel conditions. In the low and medium modulus conditions, all spots containing CRGDS had cell proliferation levels elevated beyond the 0 CRGDS condition, but proliferation levels did not increase with CRGDS in the high modulus condition (Fig. 5B). In the low modulus condition, VEGFR2 inhibition caused a significant decrease in proliferation levels at 0, 0.25 and 1 mM CRGDS conditions. Interestingly, proliferation levels in the 2 mM CRGDS condition increased significantly with VEGFR2 inhibition at low modulus. In the medium modulus condition, VEGFR2 inhibition caused significant proliferation decreases in the 0.5 and 2 mM CRGDS conditions, and no increases in proliferation were observed. Interestingly, this response of proliferation to CRGDS at medium modulus remained the same as when VEGFR2 was not inhibited, suggesting an insignificant role of VEGFR2 at this modulus. In the high modulus condition, significant decreases in proliferation with VEGFR2 inhibition were observed in all CRGDS concentrations except the 0 mM RGDS condition. Though there was a significant increase in proliferation in the absence of CRGDS, this proliferation level was less than proliferation levels observed with CRGDS in the other modulus conditions (Fig. 5C). Taken together, the surrounding context of synthetic hydrogel conditions dramatically changes HUVEC responses to VEGFR2 inhibition, as measured by cell proliferation.

Inhibition of VEGFR2 with SU5416 also significantly changed the CRGDS-dependent trends in tubulogenesis in all the shear modulus conditions tested. In the low shear modulus conditions, CLS length increased monotonically with CRGDS concentration and increased dramatically at 2.0 mM CRGDS (Fig. 6B,C,D). In the medium modulus condition, CLS length in spots containing CRGDS was significantly greater than lengths observed in the absence of CRGDS. However, with VEGFR2 inhibition CLS length no longer changed with CRGDS concentration at medium modulus (Fig. 6B). In the high modulus condition, CLS length in all spots containing CRGDS was significantly greater than lengths observed in the absence of CRGDS. Again, changing CRGDS concentrations did not change CLS length, and CLS lengths at all CRGDS concentrations were lower than CLS lengths in the medium modulus condition. Remarkably, despite these changes in CLS trends, VEGFR2 inhibition did not cause significant changes to CLS length in most hydrogel conditions when compared to growth medium controls (Fig. 6C). Only 3 hydrogel conditions saw any significant effects with VEGFR2 inhibition: increased CLS length in low modulus, 2 mM CRGDS spots, decreased CLS length in medium modulus, 0 mM CRGDS spots, and decreased CLS length in high modulus, 1 mM CRGDS spots. These data are in stark contrast to VEGFR2 inhibition in Matrigel, which resulted in a clear decrease in CLS length. Taken together, our data demonstrated that the context of surrounding hydrogel conditions dramatically change HUVEC responses to VEGFR2 inhibition, as measured by HUVEC viability, proliferation, and tubulogenesis.

Tubulogenesis in confined and non-confined hydrogels

One distinction of the hydrogel array presented in this study when compared to many prior studies is the degree to which the hydrogel is physically confined. For example, hydrogels formed in standard plastic well-plates, or elastomeric devices are typically highly confined, while the hydrogel spots in our array platform are allowed to swell in concert with the background hydrogel. To further understand the comparison between CLS formation in hydrogels confined to rigid substrates versus unconfined hydrogels, we qualitatively observed the spatial distribution of CLS formation in hydrogels that were either confined to 48 well plates or detached from substrates and allowed to freely swell in medium. The confined hydrogels were susceptible to physical “buckling” during swelling, resulting in an out-of-focus area in the middle of the hydrogels (Supp. Fig. 1A). Buckling caused heterogeneity in CLS formation, with most of the structures forming around the edge of the buckled hydrogel area. In contrast, CLS formation in the non-confined hydrogels occurred homogeneously throughout the volume of the hydrogel (Supp. Fig. 1B), similar to our observations in hydrogel array spots in this study. These observations suggest that cell encapsulation in confined hydrogels can introduce lurking variables upon swelling that significantly affect the outcome of a 3D neovascularization experiment.

Discussion

In this study we simultaneously adjusted cell adhesion ligand concentration, shear modulus and VEGF signaling in an arrayed hydrogel construct that enabled comprehensive screening of HUVEC viability, proliferation, and tubulogenesis. Over the course of these studies, we were able to form and analyze HUVEC behavior in over 900 hydrogel spots total. Previous studies have often modulated cell interactions with extracellular environments by including or not including biological signaling molecules in the matrix [28, 57] as well as using antibodies or siRNA to activate or inactivate receptors to external signals [16]. In contrast, here we modulated cell adhesion to the matrix by tuning CRGDS concentrations over a range of values rather than completely activating or inactivating integrin signaling. Simultaneously modulating CRGDS concentration in concert with hydrogel modulus, while also toggling VEGFR2 signaling, enabled us to study how changing levels of ECM cues affects synergy between multiple signaling sources. This task would not be readily achievable in larger-scale hydrogels or naturally-derived ECMs due to the number of distinct variables and outcomes of interest. We can generally conclude that combinatorially varied ECM cues affect the outcomes of HUVEC viability, proliferation and tubulogenesis, and that hydrogel conditions change HUVEC responses to VEGFR2 inhibition. A series of more focused conclusions can be drawn from the data. Specifically, excessive CRGDS concentrations in PEG hydrogels removed apparent synergy between VEGFR2 and integrin-mediated cell adhesion in the context of maintaining cell viability, proliferation in 3D culture depended on modulus and VEGFR2 inhibition but did not correlate linearly with CRGDS concentration, and ECM properties generally played a larger role in dictating CLS formation than VEGFR2 inhibition.

Previous studies have defined AKT-mediated signaling pathways that promoted increased cell viability [58] and were initiated by VEGFR2 phosphorylation and binding of αVβ3 integrin to cell adhesion ligands [59]. VEGFR2 and αVβ3 integrins are also known to behave synergistically, as binding of αVβ3 integrins to adhesion ligands enhances VEGFR2 activity and vice-versa [16]. The proposed mechanism behind this synergy was that the β3 integrin subunit must bind directly to the VEGFR2 via the cytoplasmic domain [60]. Our cell viability data were consistent with these previous studies, as non-inhibited VEGFR2 signaling and increased CRGDS concentration in the hydrogels individually and cooperatively increased HUVEC viability (Fig. 4A,B). However, we also found that VEGFR2 signaling did not contribute to increased cell viability in environments that contained the highest concentrations of CRGDS (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that, while VEGFR2 and cell adhesion to the ECM work together to promote cell viability, excessive adhesion to the surrounding ECM may interfere with this synergy.

We evaluated HUVEC proliferation levels in the hydrogel arrays and found that adhesion, modulus and VEGFR2 modulated proliferation differently than viability. Proliferation levels increased beyond baseline levels in hydrogels containing CRGDS and generally decreased with VEGFR2 inhibition (Fig. 5). These results were predictable given previously established dependences of proliferation on αVβ3 integrin [11] and VEGFR2 signaling [3], as well as our experiment where VEGFR2 inhibition reduced proliferation in standard 2D HUVEC culture (Fig. 7A). However, once CRGDS was included in the hydrogels we commonly observed biphasic trends in proliferation relating to CRGDS rather than monotonic increases in proliferation with increased CRGDS. Our group and others have previously demonstrated that increased RGD density on well-defined surfaces increased cell proliferation monotonically for multiple cell types, including HUVECs [3, 11, 30]. The fact that our results here contradicted previous studies are understandable in view of the known differences in cell-ECM interactions in 2D versus 3D environments [61]. We also observed significantly different effects of VEGFR2 inhibition between the different modulus conditions, indicating a role of the ECM in determining how VEGFR2 modulates proliferation. However, beyond combinatorial receptor-ligand interactions which require further characterization in 3D contexts, it is likely that other factors such as cell-cell contact and matrix degradation played major roles in modulating proliferation in our synthetic 3D environments. For example, we observed that proliferating cells were always associated with multicellular structures (Fig. 5D), indicating that cell-cell contact is an important parameter.

We evaluated capillary-like structure (CLS) formation by HUVECs in our hydrogels and first observed that optimized CRGDS concentrations and hydrogel modulus maximized structure formation while VEGFR2 was not inhibited (Fig. 6A). These results agree with results of previous studies in literature. For example, moderate concentrations of RGD permitted optimal angiogenic sprouting from aortic ring explants into fibrin hydrogels, while excessive RGD inhibited endothelial cell migration and vascular growth [10]. In other studies vascular growth of human dermal microvascular ECs and bovine pulmonary microvascular ECs into collagen hydrogels were inhibited when stiffness was too low to support tubule stability or too high to permit cell migration [41, 62]. It should be noted that the low end of the stiffness ranges in these prior studies fell below our low modulus condition and the high end of the ranges was equivalent to our medium modulus condition. Yamamura et al proposed that increasing collagen hydrogel stiffness by increasing collagen fibril density encourages cell aggregation and network formation rather than migration and invasion of individual cells [62]. The increased CLS formation observed in our medium modulus hydrogels corroborates this finding, and we also showed that our high modulus hydrogels inhibits CLS formation.

Multiple results here demonstrated that the effects of VEGFR2 inhibition are highly context-dependent. For example, VEGFR2 inhibition increased proliferation in the 2.0 mM CRGDS, low modulus PEG hydrogels, but decreased proliferation in 2D culture on tissue-culture polystyrene. Interestingly, the context-dependence of VEGFR2 inhibition in some cases even showed trends that contrast with the expected effects of a VEGFR2 inhibitor. For example, we found that there was no significant effect of VEGFR2 inhibition on CLS formation in synthetic hydrogel networks (Fig. 6C). The notable exception to this finding was the low modulus hydrogel containing 2.0 mM CRGDS. Whereas CLS formation in the other CRGDS concentrations was largely unchanged by VEGFR2 inhibition, CLS formation dramatically increased with VEGFR2 inhibition. This suggests that normal VEGFR2 can have an inhibitory effect on CLS formation in particular extracellular environments.

Though the roles of cell adhesion and modulus during vascularization in 3D hydrogels are well-defined, the role of VEGFR2 in dictating de novo CLS formation has been unclear. Particularly, conflicting evidence exists as to whether VEGFR2 promotes or inhibits CLS formation. Hayashi et al suggested an inhibitory role of VEGFR2 in blood vessel formation by demonstrating that decreased VEGFR2 phosphorylation is necessary for lumen formation by endothelial stalk cells in mouse embryoid bodies, mouse teratomas and zebrafish models. Additionally, a previous study by our group demonstrated that VEGFR2 activation via soluble VEGF stimulation disrupted in-vitro tubule network formation by HUVECs under a Matrigel overlay [3]. Conversely, Roberts et al suggested a stimulatory role of VEGFR2 by demonstrating that ERK5 activation by VEGFR2 is necessary for in-vitro tubular network formation by human dermal microvascular endothelial cells in collagen hydrogels [58], and Stratman et al demonstrated that VEGF and bFGF signaling prime HUVECs to receive signals from hematopoietic cytokines and undergo in-vitro tubule network formation in collagen hydrogels [63]. In these examples, experiments were conducted either in vivo or in naturally-derived collagen or Matrigel models, making it difficult to assess how ECM cues and VEGFR2 activity combinatorially modulated CLS formation. To determine the extent to which our results were due to the use of synthetic, controlled hydrogels rather than naturally-derived ECM, we also subjected HUVECs to VEGFR2 inhibition in Matrigel and found a clear reduction of tubulogenesis observed in Matrigel, contrasting with our results in PEG (Fig. 7B,C). It is well known that Matrigel, derived from a mouse sarcoma, consists of over 1000 distinct protein species at unspecified concentrations [64]. Since Matrigel is a poorly defined and variable material, it is difficult to speculate on the mechanism behind the difference in the role of VEGF. Our results have clearly demonstrated, however, that the surrounding ECM context can determine how VEGFR2 modulates CLS formation.

The combined data from the proliferation and tubulogenesis assays demonstrated that proliferation did in part correlate with CLS formation. This was especially evident in the low modulus hydrogels, where VEGFR2 inhibition resulted in monotonic increases of both proliferation and CLS formation, and where proliferation and CLS formation increased dramatically with VEGFR2 inhibition in the 2.0 mM CRGDS conditions (Fig. 5A,6A). Interestingly, while VEGFR2 activity combined with a high CRGDS concentration lowered both CLS formation and cell viability in low modulus hydrogels (Fig. 4A,6A), cell proliferation remained high in that condition (Fig. 5A). Additionally, in medium modulus hydrogels we observed no significant changes to CLS formation and few significant changes in proliferation when VEGFR2 was inhibited (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). These data collectively demonstrate that other mechanisms besides integrin-mediated cell adhesion, VEGFR2 signaling, and associated synergy are active in determining angiogenic cell behavior. Two potential candidate mechanisms could be cell-cell contact and hydrogel degradability. Chen et al had previously studied the proliferative activity of HUVECs in a number of 2D spreading and cell-cell contact contexts and noted that the extent of cell spreading dictates whether cell-cell contact increases or decreases proliferation. Specifically, VE-Cadherin engagement increased proliferation when cell spreading was restricted [65]. Based on this type of mechanism, we could speculate that the biphasic trends we observed between HUVEC proliferation and CRGDS concentration could possibly be attributable to a transition between a state where low cell attachment to the ECM promotes high proliferation and a state where sufficient CRGDS concentrations promote CLS formation and increased cell-cell contacts (Fig. 5A). However, if polymer density is high enough to restrict cell migration and cytokinesis, as was likely the case in the high modulus hydrogels, proliferation and CLS formation (Fig. 5A, 6A) would be diminished as well. The disparity between low CLS formation and high proliferation in the low modulus, 2.0 mM CRGDS condition (Fig. 4A, 6A) could also be explained by increased matrix degradation as a result of VEGFR2 signaling [66, 67], leading to CLS network destabilization. We previously demonstrated that excessive hydrogel degradation via hydrolysis lowered the viability of encapsulated cells [7], which supports the notion that protease-mediated degradability of hydrogels could also affect cell viability in the current study. Each of these speculative discussion points highlight the need for detailed characterization of mechanisms that drive endothelial cell behavior in 3D environments. The array-based approach described herein and similar enhanced throughput approaches are needed to provide further mechanistic insights in future studies.

The system designed in these studies encapsulated cells in well-defined PEG hydrogels prior to cell settling, resulting in a homogeneous cell distribution throughout the dimensions of spots. The resulting hydrogel spots were mounted to an inert background hydrogel (Fig. 2). Importantly, anchoring the degradable hydrogels to a swelling substrate is critical to observing encapsulated cells in the array construct. If, alternatively, similar hydrogel formulations were allowed to form in a confined environment, such as within a rigid well-plate, swelling issues rendered the hydrogels not observable. In particular, we observed that within 24 hours of incubation many of the hydrogels formed in polystyrene well plates buckled due to high degrees of swelling (Supp. Fig 1A), making long-term imaging and maintenance of the 3D cell cultures impossible. Buckling was especially problematic, as it could act as a lurking variable that promotes non-homogenous CLS formation in the hydrogels, not to mention adding difficulty to imaging. Anchorage to a swelling substrate stabilized the hydrogel spots throughout the swelling process, being flexible enough to allow homogeneous volumetric swelling of the spots without buckling. The distribution of CLS formation in the array spots was more similar to the non-confined hydrogels rather than the confined hydrogels. Any structures that formed in the hydrogel array spots were distributed homogeneously throughout the gel by 24 hours after encapsulation (Fig. 6D). This suggests that attachment of hydrogel spots to a swelling substrate effectively nullifies the effects of confinement.

Conclusions

Using a hydrogel array, we have combinatorially manipulated cell adhesion and stiffness to examine critical endothelial cell behaviors – viability, proliferation, and capillary-like structure (CLS) formation. The screening system designed here analyzed HUVEC behavior in over 900 spots total. The characteristics of the 3D ECM surrounding encapsulated HUVECs significantly influenced cell viability, proliferation and CLS formation. Further, the context provided by the surrounding ECM modulated the effects of VEGFR2 signaling, ranging from changing the effectiveness of synergistic interactions between integrins and VEGFR2 to determining whether VEGFR2 upregulates, downregulates or has no effect on proliferation and CLS formation. The differences in cell behavior due to combinatorially manipulated environmental parameters shown here highlight the need for additional characterization of 3D cell-matrix interactions, as well as further mechanistic studies of how these interactions modulate cell behavior.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental figure 1: Hydrogel homogeneity and heterogeneity in confined vs. non-confined PEG hydrogels. A) Hydrogels confined to a 48 well plate at 24 hours after encapsulation. Schematic: Cell-containing hydrogel is anchored by the edges by a background hydrogel (blue rectangles) in order to prevent complete detachment of the hydrogel into medium during swelling. Black circle: buckling area. Arrowheads: CLS formation. B) Freely-swollen hydrogels at 24 hours after encapsulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 HL093282-01A1, NIH R21 EB016381-01, NIH 1UH2 TR000506-01 and the Biotechnology Training Program NIGMS 5T32GM08349) as well as the UW Madison Graduate Engineering Research Scholars program. We would like to thank Justin Williams and David Beebe for their assistance with soft lithography techniques. This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grants P41RR02301 (BRTP/NCRR) and P41GM10399 (NIGMS). Additional equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin, the NIH (RR02781, RR08438), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), the DOE, and the USDA. Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) equipment was purchased with funds from NIH grant S100RR027000 (NCRR). Mechanical testing data was obtained using the Ares LS2 rheometer at the UW Madison Soft Materials Laboratory. Confocal Microscopy images were taken using the Nikon A1R-Si Confocal Microscope at the Waisman Center Cellular & Molecular Neuroscience Core facility in Madison, WI. Special thanks go Justin Koepsel for helpful discussions and technical instruction throughout the course of these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.De Smet F, Segura I, De Bock K, Hohensinner P, Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of vessel branching filopodia on endothelial tip cells lead the way. Arterioscl Thromb Vas. 2009;29:639–49. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–4. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koepsel J, Nguyen E, Murphy W. Differential effects of a soluble or immobilized VEGFR-binding peptide. Integr Biol. 2012;4:914–24. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20055d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy J, Fitzgerald D. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) induces cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent proliferation of endothelial cells (EC) via the VEGF-2 receptor. Faseb J. 2001;15:1667–69. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0757fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber H, McMurtrey A, Kowalski J, Yan M, Keyt B, Dixit V, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase AKT signal transduction pathway - requirement for FLK-1/KDR activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30336–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkefors I, Le Jan S, Jakobsson L, Hejll E, Carlson G, Johansson H, et al. Endothelial cell migration in stable gradients of vascular endothelial growth factor a and fibroblast growth factor 2 - effects on chemotaxis and chemokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13905–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jongpaiboonkit L, King WJ, Lyons GE, Paguirigan AL, Warrick JW, Beebe DJ, et al. An adaptable hydrogel array format for 3-dimensional cell culture and analysis. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3346–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jongpaiboonkit L, King WJ, Murphy WL. Screening for 3D environments that support human mesenchymal stem cell viability using hydrogel arrays. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2009;15:343–53. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King WJ, Jongpaiboonkit L, Murphy WL. Influence of FGF2 and PEG hydrogel matrix properties on hMSC viability and spreading. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93A:1110–23. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen C, Raghavan S, Xu Z, Baranski J, Yu X, Wozniak M, et al. Decreased cell adhesion promotes angiogenesis in a PYK2-dependent manner. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:1860–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koepsel J, Loveland S, Schwartz M, Zorn S, Belair D, Le N, et al. A chemically-defined screening platform reveals behavioral similarities between primary human mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells. Integr Biol. 2012;4:1508–21. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20029e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon JJ, Saik JE, Poche RA, Leslie-Barbick JE, Lee SH, Smith AA, et al. Biomimetic hydrogels with pro-angiogenic properties. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3840–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahabeleshwar G, Feng W, Reddy K, Plow E, Byzova T. Mechanisms of integrin-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor cross-activation in angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:570–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodivala-Dilke K. Alpha v beta 3 integrin and angiogenesis: a moody integrin in a changing environment. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan ZA, Chan BM, Uniyal S, Barbin YP, Farhangkhoee H, Chen S, et al. EDB fibronectin and angiogenesis -- a novel mechanistic pathway. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:183–96. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-9017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soldi R, Mitola S, Strasly M, Defilippi P, Tarone G, Bussolino F. Role of alpha(v)beta(3) integrin in the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Embo J. 1999;18:882–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammoto A, Connor K, Mammoto T, Yung C, Huh D, Aderman C, et al. A mechanosensitive transcriptional mechanism that controls angiogenesis. Nature. 2009;457:1103–08. doi: 10.1038/nature07765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryan B, Dennstedt E, Mitchell D, Walshe T, Noma K, Loureiro R, et al. RhoA/ROCK signaling is essential for multiple aspects of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Faseb J. 2010;24:3186–95. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beer A, Lorenzen S, Metz S, Herrmann K, Watzlowikl P, Wester H, et al. Comparison of integrin alpha(v)beta(3) expression and glucose metabolism in primary and metastatic lesions in cancer patients: a PET study using F-18-galacto-RGD and F-18-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:22–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox T, Erler J. Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:165–78. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Provenzano P, Inman D, Eliceiri K, Knittel J, Yan L, Rueden C, et al. Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. Bmc Med. 2008;6 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-11. Available from URL: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/6/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conklin M, Eickhoff J, Riching K, Pehlke C, Eliceiri K, Provenzano P, et al. Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am J of Pathol. 2011;178:1221–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaehler J, Zilla P, Fasol R, Deutsch M, Kadletz M. Precoating substrate and surface configuration determine adherence and spreading of seeded endothelial-cells on polytetrafluoroehtylene grafts. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:535–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koepsel JT, Murphy WL. Patterning discrete stem cell culture environments via localized self-assembled monolayer replacement. Langmuir. 2009;25:12825–34. doi: 10.1021/la901938e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudalla G, Koepsel J, Murphy W. Surfaces that sequester serum-borne heparin amplify growth factor activity. Adv Mater. 2011;23:5415–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochsner M, Dusseiller M, Grandin H, Luna-Morris S, Textor M, Vogel V, et al. Micro-well arrays for 3D shape control and high resolution analysis of single cells. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1074–7. doi: 10.1039/b704449f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charnley M, Textor M, Khademhosseini A, Lutolf M. Integration column: microwell arrays for mammalian cell culture. Integr Biol. 2009;1:625–34. doi: 10.1039/b918172p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leslie-Barbick JE, Moon JJ, West JL. Covalently-immobilized vascular endothelial growth factor promotes endothelial cell tubulogenesis in poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2009;20:1763–79. doi: 10.1163/156856208X386381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders R, Hammer D. Assembly of human umbilical vein endothelial cells on compliant hydrogels. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2010;3:60–7. doi: 10.1007/s12195-010-0112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung J, Moyano J, Collier J. Multifactorial optimization of endothelial cell growth using modular synthetic extracellular matrices. Integr Biol. 2011;3:185–96. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00112k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stratman A, Saunders W, Sacharidou A, Koh W, Fisher K, Zawieja D, et al. Endothelial cell lumen and vascular guidance tunnel formation requires MT1-MMP-dependent proteolysis in 3-dimensional collagen matrices. Blood. 2009;114:237–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacharidou A, Koh W, Stratman A, Mayo A, Fisher K, Davis G. Endothelial lumen signaling complexes control 3D matrix-specific tubulogenesis through interdependent CDC42-and MT1-MMP-mediated events. Blood. 2010;115:5259–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanjaya-Putra D, Yee J, Ceci D, Truitt R, Yee D, Gerecht S. Vascular endothelial growth factor and substrate mechanics regulate in vitro tubulogenesis of endothelial progenitor cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2436–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lafleur M, Handsley M, Knauper V, Murphy G, Edwards D. Endothelial tubulogenesis within fibrin gels specifically requires the activity of membrane-type-matrix metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs) J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3427–38. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Saux G, Magenau A, Gunaratnam K, Kilian K, Bocking T, Gooding J, et al. Spacing of integrin ligands influences signal transduction in endothelial cells. Biophys J. 2011;101:764–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Tirrell D. Cell response to RGD density in cross-linked artificial extracellular matrix protein films. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2984–8. doi: 10.1021/bm800469j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers K, Applegate K, Danuser G, Fischer R, Waterman C. Distinct ECM mechanosensing pathways regulate microtubule dynamics to control endothelial cell branching morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:321–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker B, Chen C. Deconstructing the third dimension – how 3D culture microenvironments alter cellular cues. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abaci H, Truitt R, Tan S, Gerecht S. Unforeseen decreases in dissolved oxygen levels affect tube formation kinetics in collagen gels. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph. 2011;301:C431–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00074.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calvani M, Rapisarda A, Uranchimeg B, Shoemaker R, Melillo G. Hypoxic induction of an HIF-1 alpha-dependent bFGF autocrine loop drives angiogenesis in human endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;107:2705–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shamloo A, Heilshorn S. Matrix density mediates polarization and lumen formation of endothelial sprouts in VEGF gradients. Lab Chip. 2010;10:3061–8. doi: 10.1039/c005069e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv Mater. 2009;21:5005–10. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoyle C, Bowman C. Thiol-ene click chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1540–73. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gobaa S, Hoehnel S, Roccio M, Negro A, Kobel S, Lutolf M. Artificial niche microarrays for probing single stem cell fate in high throughput. Nat Methods. 2011;8:949–55. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albrecht D, Tsang V, Sah R, Bhatia S. Photo- and electropatterning of hydrogel-encapsulated living cell arrays. Lab Chip. 2005:111–8. doi: 10.1039/b406953f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albrecht D, Underhill G, Wassermann T, Sah R, Bhatia S. Probing the role of multicellular organization in three-dimensional microenvironments. Nat Methods. 2006;3:369–75. doi: 10.1038/nmeth873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khoo C, Micklem K, Watt S. A Comparison of Methods for Quantifying Angiogenesis in the matrigel assay in vitro. Tissue Eng Pt C-Meth. 2011;17:895–906. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toepke MW, Impellitteri NA, Theisen JM, Murphy WL. Characterization of thiol-ene crosslinked PEG hydrogels. Macromol Mater Eng. 2013;298:699–703. doi: 10.1002/mame.201200119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagase H, Fields GB. Human matrix metalloproteinase specificity studies using collagen sequence-based synthetic peptides. Biopolymers. 1996;40:399–416. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1996)40:4%3C399::AID-BIP5%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jo BH, Van Lerberghe LM, Motsegood KM, Beebe DJ. Three-dimensional micro-channel fabrication in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer. J Microelectromech S. 2000;9:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thibault C, Severac C, Mingotaud A, Vieu C, Mauzac M. Poly(dimethylsiloxane) contamination in microcontact printing and its influence on patterning oligonucleotides. Langmuir. 2007;23:10706–14. doi: 10.1021/la701841j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendel D, Schreck R, West D, Li G, Strawn L, Tanciongco S, et al. The angiogenesis inhibitor SU5416 has long-lasting effects on vascular endothelial growth factor receptor phosphorylation and function. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4848–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan R, Titze I. Viscoelastic shear properties of human vocal fold mucosa: Measurement methodology and empirical results. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;106:2008–21. doi: 10.1121/1.427947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinkus R, Tanter M, Xydeas T, Catheline S, Bercoff J, Fink M. Viscoelastic shear properties of in vivo breast lesions measured by MR elastography. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneider B, Miller K. Angiogenesis of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1782–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leslie-Barbick J, Saik J, Gould D, Dickinson M, West J. The promotion of microvasculature formation in poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels by an immobilized VEGF-mimetic peptide. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5782–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts O, Holmes K, Muller J, Cross D, Cross M. ERK5 is required for VEGF-mediated survival and tubular morphogenesis of primary human microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3189–200. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han S, Jung Y, Lee E, Park H, Kim G, Jeong J, et al. DICAM inhibits angiogenesis via suppression of AKT and p38 MAP kinase signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:73–82. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cebe-Suarez S, Zehnder-Fjallman A, Ballmer-Hofer K. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:601–15. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens D, Yamada K. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamamura N, Sudo R, Ikeda M, Tanishita K. Effects of the mechanical properties of collagen gel on the in vitro formation of microvessel networks by endothelial cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1443–53. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stratman A, Davis M, Davis G. VEGF and FGF prime vascular tube morphogenesis and sprouting directed by hematopoietic stem cell cytokines. Blood. 2011;117:3709–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hughes C, Postovit L, Lajoie G. Matrigel: A complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics. 2010;10:1886–90. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson C, Chen C. VE-cadherin simultaneously stimulates and inhibits cell proliferation by altering cytoskeletal structure and tension. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3571–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu Z, Yu Y, Duh E. Vascular endothelial growth factor upregulates expression of ADAMTS1 in endothelial cells through protein kinase C signaling. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2006;47:4059–66. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Funahashi Y, Shawber CJ, Sharma A, Kanamaru E, Choi YK, Kitajewski J. Notch modulates VEGF action in endothelial cells by inducing matrix metalloprotease activity. Vasc Cell. 2011;3 doi: 10.1186/2040-2384-2-3. Available from URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21349159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials