Abstract

Background

Teicoplanin is a glycopeptide antibiotic that is widely used in clinical practice for the treatment of infections caused by drug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria. The aim of this study was to analyze plasma teicoplanin concentrations to determine the percentage of patients in whom therapeutic concentrations of teicoplanin were achieved in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

The plasma teicoplanin concentrations of hospitalized patients receiving treatment at a teaching hospital were retrospectively analyzed. The target level was defined as a plasma teicoplanin concentration of 10 mg/L or greater, since this was generally regarded as the lower limit of the optimal concentration range required for the effective treatment of a majority of infections.

Results

Patients with sub-optimal (< 10 mg/L) plasma teicoplanin concentrations constituted nearly half of the total study population. The majority of these patients received the recommended loading dose, which were three 400 mg doses administered every 12 hours. Sub-group analysis showed a trend that the group receiving loading dose was more likely to reach the optimal teicoplanin concentration.

Conclusions

The data revealed that a significant proportion of patients in clinical practice achieved only sub-optimal teicoplanin concentrations, which emphasizes the importance of the mandatory use of loading dose and routine therapeutic drug monitoring. Treatment reassessment and simulation of individual dose regimens may also be necessary to achieve optimal drug concentrations.

Keywords: Teicoplanin, Drug monitoring, Loading dose, Dosing regimen

Introduction

Like vancomycin, teicoplanin is a glycopeptide antibiotic that is widely used in clinical practice in the treatment of infections caused by multi-drug resistant Gram-positive bacteria. These two antibiotics have similar efficacy and antibacterial spectrum against gram-positive pathogenic bacteria, except for the VanB class vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which are susceptible to teicoplanin treatment [1-2]. Compared to vancomycin, teicoplanin is significantly less toxic, particularly in terms of nephrotoxicity [1,2,3,4]. Besides being associated with lower incidence of adverse events, teicoplanin treatment has other advantages over vancomycin, such as once-daily bolus administration regimen and the use of the intramuscular route for injection. Red man syndrome, associated with histamine release after vancomycin administration, is also very rare in teicoplanin treatment [2]. Because teicoplanin requires considerable time to reach steady-state concentrations, the recommended dosing regimen includes a loading dose administered 3 times at 12 hour intervals, followed by a once-daily dose of at least 6 mg/L thereafter. Harding et al. [5] described successful teicoplanin treatment of Staphylococcus aureus septicemia with trough plasma teicoplanin concentrations of > 10 mg/L. However, trough teicoplanin concentrations > 20 and 30 mg/L are considered necessary for the treatment of endocarditis and for deep-seated bone and joint infections caused by S. aureus, respectively [6-7]. Monitoring of plasma teicoplanin concentrations is necessary when high doses of the antibiotic are administered. Tobin et al. [8] analyzed plasma concentrations in more than 10,000 patient samples and found that optimal teicoplanin concentrations were not achieved in a significant proportion of patients. Pea et al. [9] suggested that therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and appropriate loading doses of teicoplanin should be mandatory because of potential treatment failure due to suboptimal concentrations of circulating teicoplanin. However, TDM of teicoplanin is currently not performed routinely in clinical practice.

This study investigated the percentage of patients in routine clinical practice in whom the required therapeutic plasma concentrations of teicoplanin could be achieved. To our knowledge, this is the first report to evaluate the TDM of teicoplanin in Korea.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

We analyzed the plasma teicoplanin concentrations of hospitalized patients who were treated with teicoplanin for suspected or documented infections with multi-drug resistant Gram-positive bacteria at an 850-bed tertiary teaching hospital between September 2010 and August 2011. Three consecutive 400 mg loading doses administered every 12 hours were followed by maintenance doses of 400 mg administered once daily for those patients whose renal function test results were within the normal range. The maintenance dose was adjusted for patients with compromised renal function. Pea et al. [9] suggested that optimal teicoplanin plasma concentrations were achieved after at least four days of therapy, given that 10 mg/L is considered the minimum recommended plasma concentration for effective treatment of serious infections. To exclude samples taken during steady-state conditions and to assess whether the loading dose helped achieve optimal drug concentration, we evaluated patient samples collected within three days from the start of treatment. Blood samples were drawn immediately before administration of the maintenance dose to measure trough teicoplanin levels. Expert advice on the adjustment of teicoplanin dose based on the TDM results was not provided; therefore, determination of individualized maintenance dosing regimens was at the discretion of the treating physicians. The target level was defined as a plasma teicoplanin concentration of 10 mg/L or greater, since this concentration is generally regarded as the lower limit of the optimal drug concentration for treating a majority of infections. The following data were analyzed from clinical recording charts: patient demographics; laboratory test results, including serum creatinine levels (mg/dL), creatinine clearance (CLcr) estimated using the Cockcroft & Gault formula to assess renal function, and serum albumin levels (g/dL); detailed information on the administration of teicoplanin injections (loading and maintenance doses decided on by the treating physician; diagnosed medical conditions that required teicoplanin therapy; reasons for preference of teicoplanin to vancomycin; and the presence of other underlying diseases. The Institutional Review Board of the Inha University Hospital fully approved the use of this database and the study protocol. (IRB No. 11-2212)

2. Drug analysis

Teicoplanin concentrations were calculated by measuring the serum levels of A2-2 component, one of the main constituents of teicoplanin, by high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric (LC/MS/MS system) detection methods (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and column switching apparatus (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan). Inter- and intra-day concentration variations were not investigated.

A teicoplanin standard solution was prepared by dissolving the drug in distilled water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. A sulfamethoxazole solution as internal standard solution was prepared at a concentration of 1 ug/mL in distilled water. Working standards were prepared by diluting the standard solutions with pooled human sera that were free of teicoplanin. Final concentrations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 25, and 50 µg/mL were used for the assessment of the assay procedure. Standard serum (20 µL) was mixed with 10 µL of internal standards, 1% formic acid, and 0.2 mL of water and centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 rpm. From the final filtrate volume, 2 µL of the filtrate was used for liquid chromatography analysis (Agilent 1200 System, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The calibration curve was determined from the ratio of teicoplanin peak areas to that of the internal standard sample.

3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were expressed as median and ranges. Discrete variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U and the Chi-square tests, respectively (SPSS, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among groups were considered statistically significant when P-values were less than 0.05.

Results

1. Patients

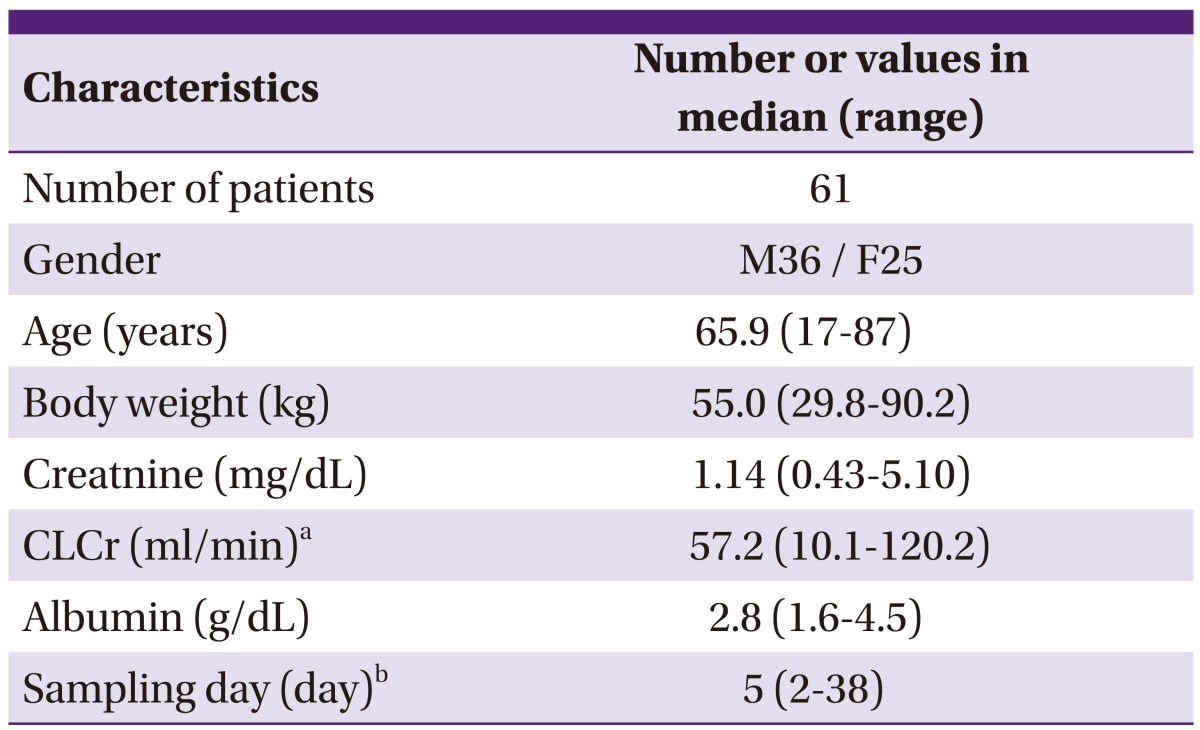

The data of 61 patients were retrospectively analyzed, as shown in Table 1. Of these, 36 were men and 25 were women; the median (range) of age and body weight, were 65.8 (17-87) years and 55.0 (29.8-90.2) kg, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

aCLCr: calculated using Cockcroft-Gault equation.

bSampling day: initial sampling time after first teicoplanin administration.

2. Use of teicoplanin

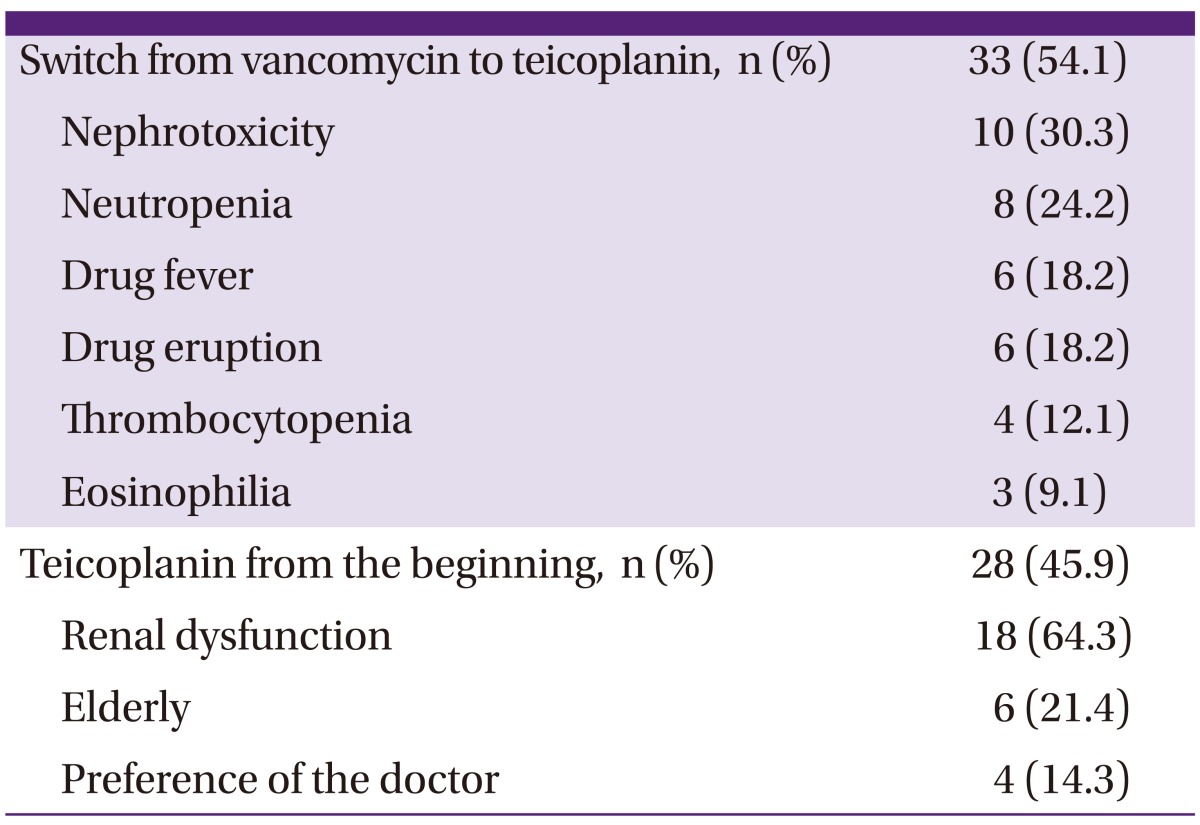

The median time for collection of blood samples was 5 days after the first administration of teicoplanin, with a range of 2 to 38 days. The maximum number of patients who received teicoplanin treatment were those with a diagnosis of pneumonia (n = 24); followed by surgical-site or prosthesis-related infections (n = 18); other skin and soft tissue or bone and joint infections (n = 11); catheter-related blood stream infections (n = 10); and other disorders, including febrile neutropenia, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections of unknown origin, and other infections (n = 7). Nine patients had more than one cause for teicoplanin treatment. The reasons for administering teicoplanin instead of vancomycin therapy are listed in Table 2. Twenty-eight patients (45.9%) received teicoplanin as a primary treatment, and 33 (54.1%) were switched from vancomycin to teicoplanin because of the following reasons: vancomycin-related nephrotoxicity, neutropenia, drug fever, drug eruption, thrombocytopenia, and eosinophilia, in decreasing order. In some patients, teicoplanin was selected as the primary treatment based on their renal impairment, age, or physician preference.

Table 2.

Reasons for the use of teicoplanin over vancomycin

3. Plasma teicoplanin concentration

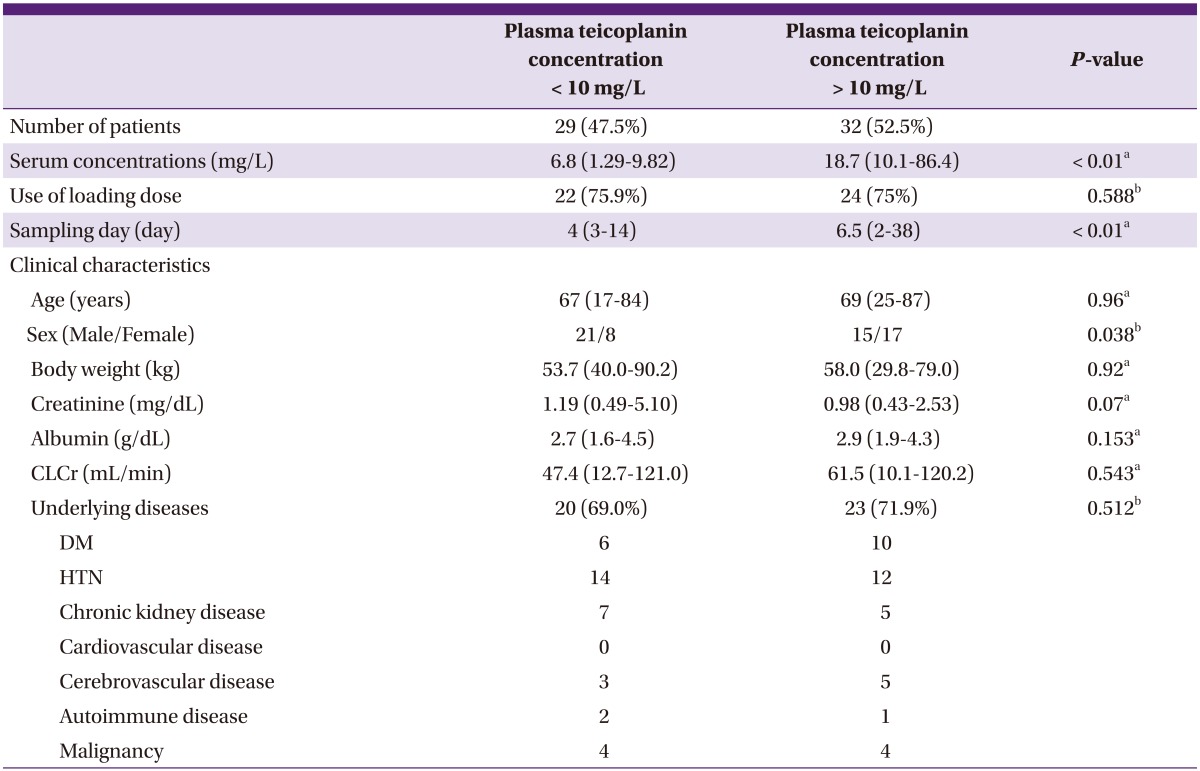

In nearly 50% (n = 29/61, 47.5%) of the patients, the levels of plasma teicoplanin (< 10 mg/L) were sub-optimal (Table 3). The median plasma teicoplanin concentration was 6.8 mg/L, and the majority of patients (22/29, 75.9%) had received loading doses as recommended, which was three 400 mg doses administered every 12 hours. The median sampling time was the fourth day after the first dose of teicoplanin; all patients were administered teicoplanin at least two days before TDM was performed. These results indicate that most patients in this group failed to achieve optimal drug concentrations even though they had received appropriate loading doses. There were no statistically significant differences in serum concentrations of creatinine and albumin, estimated renal function, and basic demographics except gender distribution between groups with optimal and sub-optimal plasma teicoplanin concentrations.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis according to plasma teicoplanin concentration

CLCr: creatinine clearance estimated on the basis of the Cockcroft & Gault formula.

Values represent median (range) unless otherwise stated.

aMann-Whitney U-test.

bChi-squared test.

4. Use of loading dose

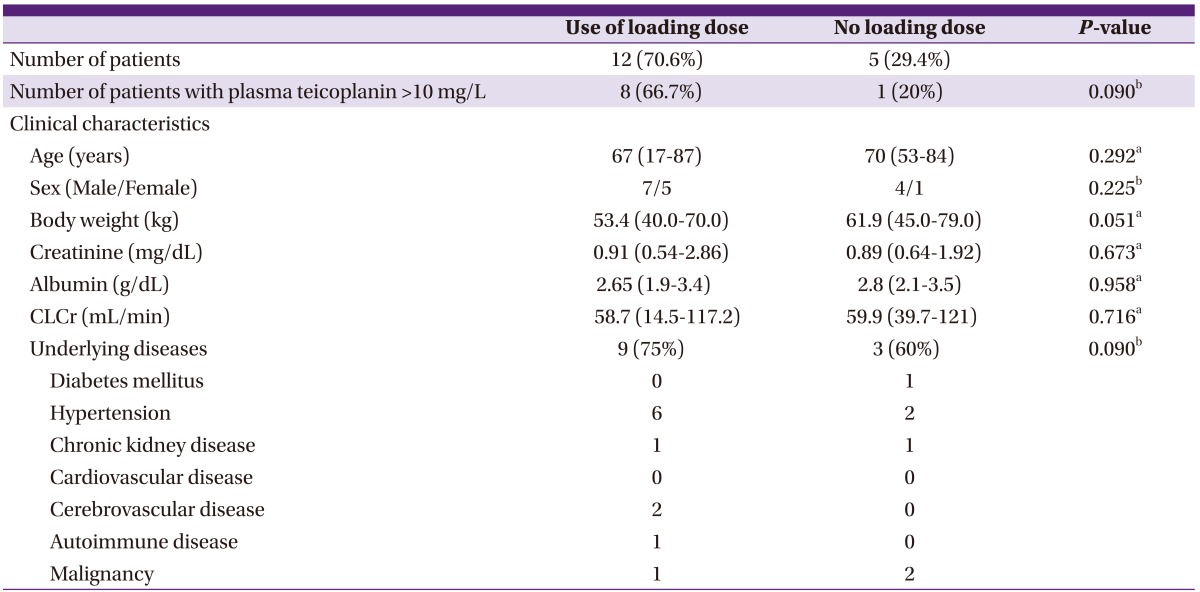

In the case of 17 of all study patients, TDM samples were drawn within 3 days from the beginning of treatment; the data of these patients were analyzed. Twelve (70.6%) patients had received a loading dose; among these, 66% (n = 8) achieved plasma teicoplanin concentrations of 10 mg/L or greater. Among the five patients who did not receive a loading dose, only one (20%) achieved optimal plasma drug concentrations (Table 4). Although this result was not statistically significant (P = 0.09), it indicated that target therapeutic drug concentrations were more likely with the administration of a loading dose.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of plasma teicoplanin concentrations according to the administration of loading dose (blood samples were drawn from patients within 3 days after treatment initiation

CLCr: creatinine clearance estimated on the basis of the Cockcroft & Gault formula.

Values represent median (range) unless otherwise stated.

aMann-Whitney U-test.

bChi-squared test.

5. Analysis according to renal function

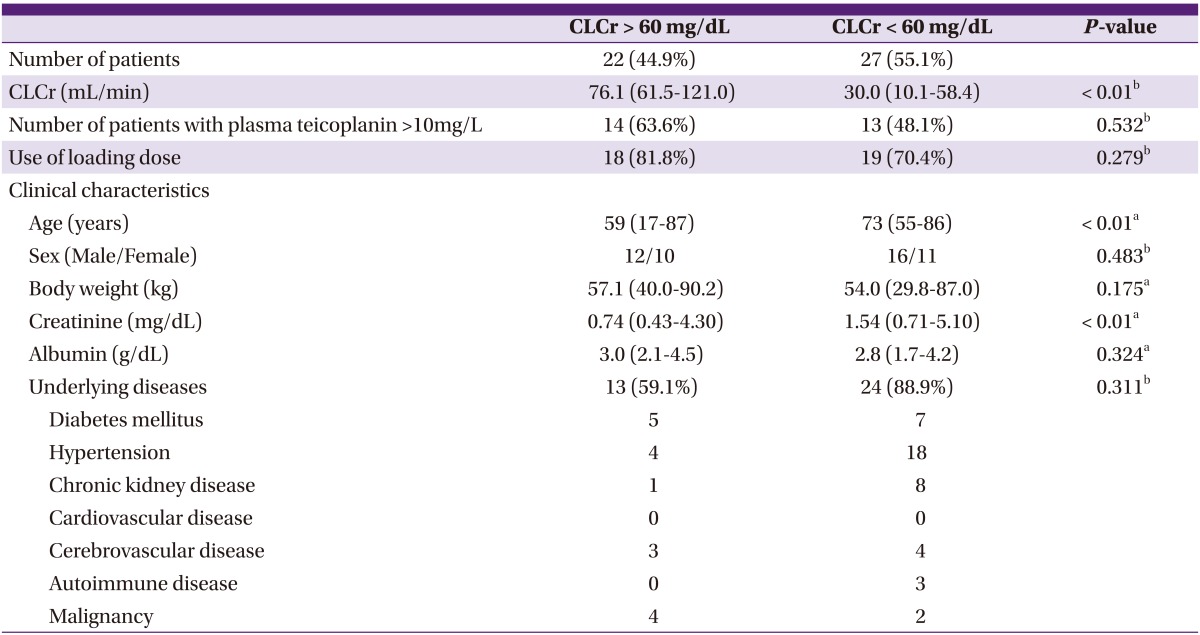

Twenty-seven of 61 patients initially showed CLcr values that were lower than 60 mg/dL. CLcr values could not be calculated for 12 patients because details of their body weights were not recorded. Out Of 27 patients with renal impairment, 13 (48%) achieved optimal drug concentrations, as against 63% of patients with normal renal function (P = 0.53) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis based on creatinine clearance

CLCr: creatinine clearance estimated on the basis of the Cockcroft & Gault formula.

Values represent median (range) unless otherwise stated.

aMann-Whitney U-test.

bChi-squared test.

Discussion

Teicoplanin has a long elimination half-life, which allows it to be administered once daily. However, because of this, steady-state concentrations of teicoplanin are achieved slowly. Therefore, an initial loading dose is mandatory to rapidly achieve therapeutic steady-state concentrations. The period of therapeutic efficacy of glycopeptide antibiotics, such as teicoplanin, is closely related to the time available after the achievement of plasma concentrations above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Peak serum teicoplanin concentrations for short durations are not likely to be clinically efficacious, which emphasizes the importance of trough levels. Pea et al. [9] observed that optimal therapeutic levels of teicoplanin were reached after at least 4 days of therapy in most cases, and they recommended administration of teicoplanin loading doses to all patients, regardless of renal function. Harding et al. [5] concluded that the probability of successful treatment of S. aureus septicemia with teicoplanin increases with increased trough concentrations, and that trough concentrations should always exceed 10 mg/L. While some evidence shows that vancomycin may be superior to teicoplanin in the treatment of endocarditis or endarteritis, the higher teicoplanin treatment failure rate might have been due to inappropriate plasma drug concentrations [10, 11]. Although it is generally accepted that trough plasma concentrations > 10 mg/L are appropriate for the majority of severe infections, higher concentrations of loading and maintenance doses are required in certain circumstances to obtain therapeutic effects [12].

This study analyzed samples obtained from patients receiving teicoplanin therapy to determine whether optimal concentrations (> 10 mg/L) were achieved and observed in routine clinical practice. Overall, the rate of achievement of optimal teicoplanin concentration was surprisingly lower than expected. Interestingly, the majority of patients with suboptimal teicoplanin concentrations had received the recommended loading dose. This unexpected result implies that the conventional loading dose of three consecutive 400 mg doses administered every 12 hours might be inadequate for some patients to rapidly achieve steady-state concentrations in the first few days of treatment. While three consecutive 6 to 12 mg/kg doses administered at 12 hour intervals is commonly suggested as loading dose regimen in many studies, package inserts in Korea recommend 3 loading doses of 400 mg every 12 hours for severe infections, although 400 mg is equivalent to 6 mg/kg for patients weighing under 85 kg. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a loading dose of 400 mg is used most frequently in Korean hospitals; however, additional large-scale studies of teicoplanin levels from a wide selection of Korean hospitals are necessary to elucidate the common treatment protocols currently used in Korea. Because the TDM sampling day varied for each patient, suboptimal plasma teicoplanin concentrations might be attributed not only to inappropriate loading dose but also to insufficient steady state concentrations. Niwa et al. [13] used a software suite that supported individualized teicoplanin TDM based on patient age, body weight, and creatinine clearance to achieve the minimum effective plasma concentration (> 10 mg/L) by day 3. The success rate for optimal trough concentration was much higher in the group that received individualized loading dose regimens than in the group that received conventional loading dose regimens. In study by Yamada et al. [14], simplified dosing regimens stratified by renal function and weight using Monte Carlo simulation based on population pharmacokinetics and observed distribution of patient characteristics were found to be helpful to estimate optimal loading and maintenance doses. These findings suggest that the loading dose is mandatory for optimal drug concentration, and that individual adjustment of initial loading and maintenance doses according to population pharmacokinetics could be potentially useful for rapidly achieving optimum levels of therapeutic drug concentrations.

Although the results were not statistically significant, we observed that patients with renal dysfunction were less likely to receive a loading dose, and the percentage of these patients with optimal drug concentrations was lower than that of patients with normal renal function. These results might be due to physician concern about potential drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Because dosages were adjusted at the discretion of each treating physician without any formal guidelines it can be assumed that some patients with renal impairment did not receive a loading dose or were administered reduced maintenance doses insufficient for adequate treatment.

In a study that investigated teicoplanin usage in the UK, researchers found that more than two-thirds of medical centers did not routinely recommend teicoplanin TDM. Physicians stated that a major advantage of using teicoplanin was that TDM was not required [6]. This perceived lack of need for teicoplanin TDM might contribute to inadequate therapeutic drug concentrations. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to measure teicoplanin levels in clinical settings in Korea. In conclusion, a significant proportion of study participants did not achieve optimal plasma teicoplanin concentrations in clinical practice, which emphasizes the importance of administering loading doses and performing routine TDM of teicoplanin. Moreover, current standard dose regimens seem insufficient for treating a certain number of study patients. Reassessment of dosing strategies or population-based individualized pharmacokinetic dose adjustments would be helpful in in achieving adequate therapeutic drug concentrations. In addition, increased clinician awareness of the significance of loading doses and drug monitoring should be encouraged through education on drug pharmacokinetic characteristics.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of this study. We especially thank the researchers from the Drug Safety Monitoring Center of Inha University Hospital for their help in determining plasma teicoplanin concentrations. This research was supported by a grant from the Korean Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A070001). This work was financially supported by the Inha University. The authors declare no commercial relationships or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Svetitsky S, Leibovici L, Paul M. Comparative efficacy and safety of vancomycin versus teicoplanin: systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4069–4079. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00341-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalcanti AB, Goncalves AR, Almeida CS, Bugano DD, Silva E. Teicoplanin versus vancomycin for proven or suspected infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD007022. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007022.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Outman WR, Nightingale CH, Sweeney KR, Quintiliani R. Teicoplanin pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers after administration of intravenous loading and maintenance doses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2114–2117. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowland M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of teicoplanin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;18:184–209. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199018030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding I, MacGowan AP, White LO, Darley ES, Reed V. Teicoplanin therapy for Staphylococcus aureus septicaemia: relationship between pre-dose serum concentrations and outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:835–841. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darley ES, MacGowan AP. The use and therapeutic drug monitoring of teicoplanin in the UK. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert DN, Wood CA, Kimbrough RC. Failure of treatment with teicoplanin at 6 milligrams/kilogram/day in patients with Staphylococcus aureus intravascular infection. The Infectious Diseases Consortium of Oregon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:79–87. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobin CM, Lovering AM, Sweeney E, MacGowan AP. Analyses of teicoplanin concentrations from 1994 to 2006 from a UK assay service. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2155–2157. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pea F, Brollo L, Viale P, Pavan F, Furlanut M. Teicoplanin therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill patients: a retrospective study emphasizing the importance of a loading dose. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:971–975. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson AP, Grneberg RN, Neu H. Dosage recommendations for teicoplanin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:792–796. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg RN. Treatment of bone, joint, and vascular-access-associated gram-positive bacterial infections with teicoplanin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2392–2397. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.12.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson AP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of teicoplanin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;39:167–183. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200039030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niwa T, Imanishi Y, Ohmori T, Matsuura K, Murakami N, Itoh Y. Significance of individual adjustment of initial loading dosage of teicoplanin based on population pharmacokinetics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada T, Nonaka T, Yano T, Kubota T, Egashira N, Kawashiri T, Oishi R. Simplified dosing regimens of teicoplanin for patient groups stratified by renal function and weight using Monte Carlo simulation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]