Abstract

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare condition causing pulmonary artery hypertension and acute right heart failure in patients with cancer. However, chest computer tomography shows negative finding of pulmonary thromboembolism. Serum D-dimer level may be elevated. Echocardiography reveals a dilated right ventricle and feature of pulmonary artery hypertension. Establishing this diagnosis can be very difficult, and most cases are diagnosed during autopsy, although a history of cancer may be a predictor. PTTM should be considered in all patients with apparent pulmonary artery hypertension and elevated D-dimer level, particularly when the patient is known to have an underlying malignancy, especially adenocarcinoma and most of all, the clinical manifestation is very rapidly progressive.

Keywords: D-dimer, gastric cancer, right heart failure

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare condition causing pulmonary artery hypertension and acute right heart failure in patients with cancer. It should be suspected in patients with unexplained severe dyspnea, pulmonary artery hypertension, and elevated D-dimer especially in the presence of adenocarcinoma. We are reporting two cases of patients presenting with acute cor pulmonale secondary to gastric cancer, suggesting a PTTM.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

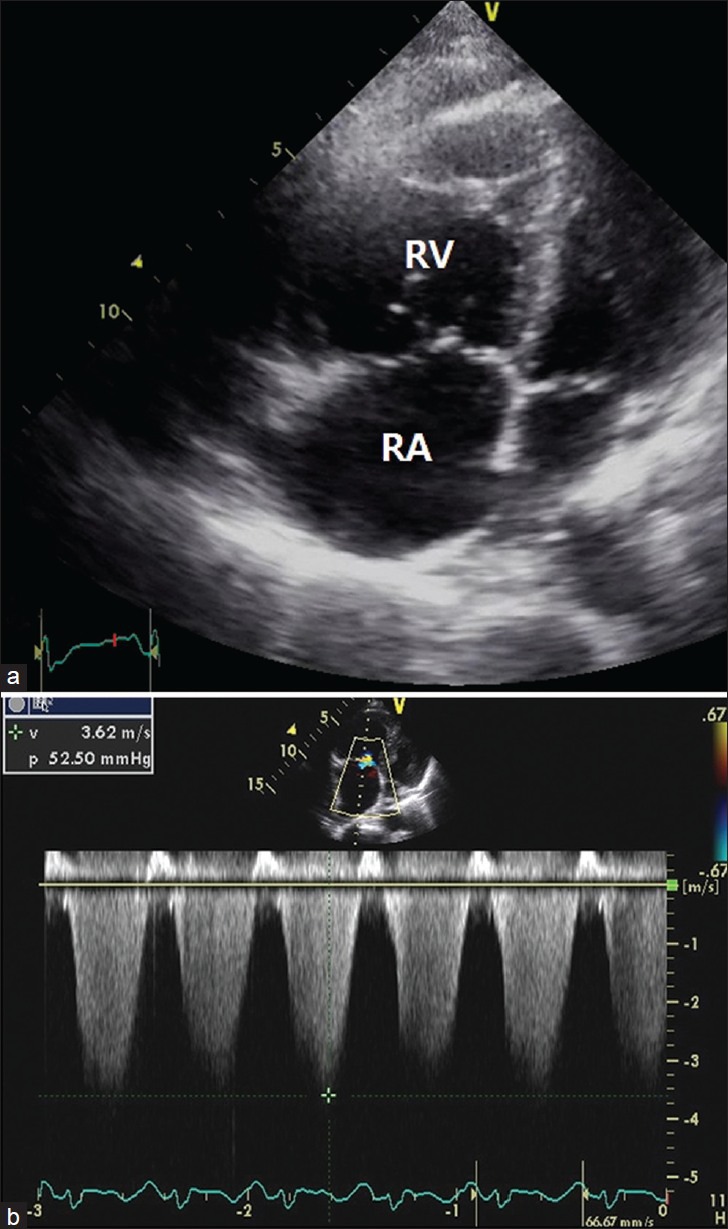

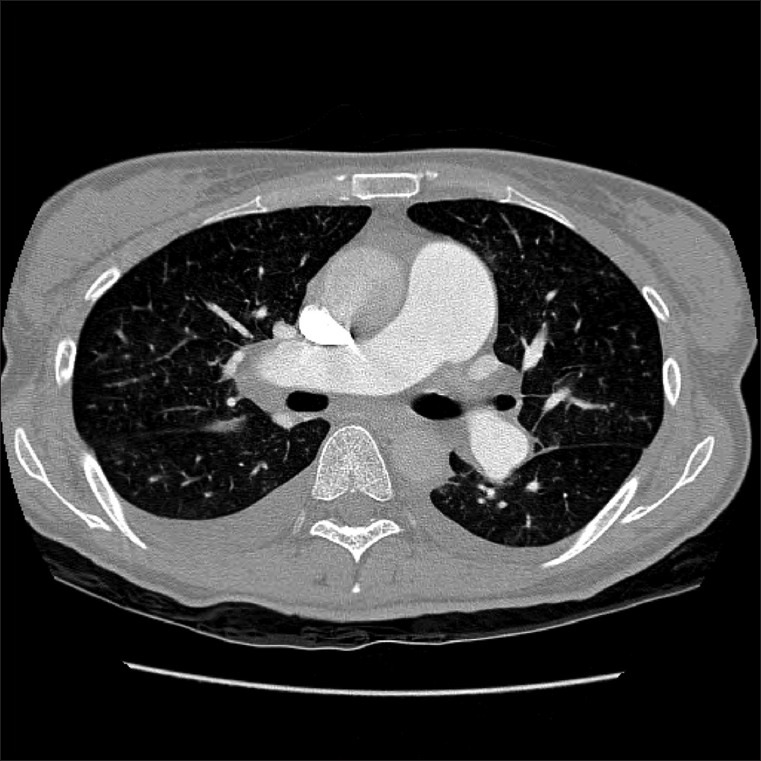

A 46-year-old woman with gastric cancer presented with a 2 week period of progressively worsening shortness of breath. Six months earlier, she had a total gastrectomy. However, the adjuvant chemotherapy was not done because of her refusal. On admission, the physical examination including auscultation was unremarkable. The patient was afebrile with tachycardia of 116/min, respiratory rate of 28/min, and blood pressure of 100 /60 mmHg. Laboratory findings were remarkable for microcytic anemia and a strong positive D-dimer (11.8 μg/mL, normal <0.55). Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Echocardiography revealed feature of pulmonary artery hypertension, namely a severely dilated right ventricle with grossly impaired systolic function and an estimated pulmonary artery pressure of 52 mmHg [Figure 1]. Chest computer tomography (CT) presented no evidence of pulmonary emboli [Figure 2]. She rapidly developed hypoxemic respiratory failure and desaturated 80% on 10 liters of oxygen. The patient's condition progressively worsened and took a rapid downhill course, despite aggressive hemodynamic support. Finally, the patient developed an intractable respiratory failure and died 14 hours after hospitalization.

Figure 1.

(a) Echocardiography showed right ventricular dilatation (b) and elevated systolic pulmonary artery pressure. RA: right atrium, RV: right ventricle

Figure 2.

Chest computer tomography revealed no evidence of filling defects within the pulmonary artery

Case 2

A 48-year-old man presented with a 2 week history of rapid progressive exertional dyspnea. His gastric cancer had been diagnosed 1 year previously and was treated with gastrectomy and chemotherapy. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile with respiratory rate of 25/min, and blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Echocardiography revealed a right ventricular overloading sign with an elevated pulmonary artery pressure of 70 mmHg. Laboratory results showed microcytic anemia and an elevated D-dimer serum level (19.1 μg/mL, normal <0.55). Chest CT presented no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism. Ten hours after hospital admission, the patient's state rapidly deteriorated, with increasing dyspnea, peripheral cyanosis. He showed poor response to the initial management with oxygen and continuous positive airway pressure. He progressed to cardiogenic shock and had no improvement with a vasoactive drug. He had persistent hypoxemia. He died from refractory right heart failure caused by pulmonary artery hypertension.

DISCUSSION

The lung is a common site for the metastatic spread of malignant tumors. Generally speaking, tumoral cells affect the pulmonary vasculature in three different ways.[1] Large tumor emboli can directly occlude the main vessel of the pulmonary tree. Second, malignant cells can spread via the lymphatic channels generating carcinomatous lymphangitis. Finally, tumor microthromboemboli may activate the tissue factor and trigger the formation of microthrombi by stimulating the proliferation of the myofibroblasts in the intimal layer of the vessel.[2] PTTM is a rare complication with a common incidence in postmortem studies.

PTTM was first described by von Herbay in 1990.[3] It was seen in 3% of the patients who died of adenocarcinoma (such as breast, prostate, lung, and pancreas adenocarcinoma): particularly in patients suffering from gastric adenocarcinoma of PTTM (around 25%) is much higher than with other tumor locations.[3,4] Thus, the most common tumor associated with PTTM is the gastric adenocarcinoma, especially that of the poorly differentiated type, including signet-ting cell carcinoma.[3]

PTTM is defined as the activation of the coagulation cascade induced by tumor cells in the lung vessel, resulting in obstructive microthrombosis and intimal fibrocellular proliferation. The pulmonary arteries are grossly normal. Tumor cells release inflammatory mediators and growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor resulting in thrombosis.[5] These fibrin-platelet microthrombi in the pulmonary arterioles result in fatal pulmonary hypertension and acute cor pulmonale. Therefore, PTTM should be distinguished from tumor embolism and carcinomatous lymphangitis.

The typical presentation is with subacute dyspnea, pulmonary artery hypertension, and right heart failure that mimics massive pulmonary embolism. In most cases, symptoms tend to be more severe than physical findings. Arterial blood gas analysis generally shows hypoxia. In addition, echocardiography may reveal a feature of pulmonary artery hypertension with severely dilated right ventricle. Chest X-ray and CT scan are usually unremarkable in the absence of lymphangitic spread. Although CT scan is considered as the exam of choice in pulmonary embolism, it is not a helpful test in PTTM. Ventilation-perfusion scanning shows multiple peripheral, subsegmental perfusion defects with a normal ventilation scan. However, invasive procedures are required to confirm the diagnosis. These procedures include transbronchial lung biopsy or surgical open lung biopsy.[6]

Antemortem diagnosis is extremely difficult due to the rapid downhill progression. Almost all patients with PTTM die within one week of the onset of dyspnea.[7]

In the presented cases, both patients died within less than 24 hours after hospitalization without ante-mortem biopsy. An autopsy was not carried out because of refusal from family members.

In general, there is no specific treatment for PTTM and the clinical course is extremely rapid progression, compared with lymphangitic cardiconmatosis. Thrombolytic therapy is not helpful because PTTM is caused by mainly intimal fibrocellular proliferation.[8] Nevertheless, chemotherapy is believed to reduce the burden of the tumor cells, thereby lessening the stimulus for the intimal proliferation.[8] Serotonin antagonist therapy may also be benefit.[2]

The case of a patient with history of gastric adenocarcinoma who presented with dyspnea and a dry cough has been reported.[6] The serum D-dimer level was elevated. The patient was early diagnosed and successfully treated with corticosteroid, anticoagulants, and oral anticancer drugs. The elevation of the D-dimer level indicates the activation of the coagulation systems. This finding is specific for PTTM.[9] The serum D-dimer level was elevated in our patients too. Serum D-dimer level may be an important feature for the early diagnosis of the PTTM, without invasive surgical biopsy. To make a definite ante-mortem diagnosis, most of all, the clinical manifestation has to be considered such as acutely and rapidly progressive dyspnea.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts KE, Hamele-Bena D, Saqi A, Stein CA, Cole RP. Pulmonary tumor embolism: A review of the literature. Am J Med. 2003;115:228–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakashita N, Yokose C, Fujii K, Matsumoto M, Ohnishi K, Takeya M. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy resulting from metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Pathol Int. 2007;57:383–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Herbay A, Illes A, Waldherr R, Otto HF. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy with pulmonary hypertension. Cancer. 1990;66:587–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<587::aid-cncr2820660330>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane RD, Hawkins HK, Miller JA, Noce PS. Microscopic pulmonary tumor emboli associated with dyspnea. Cancer. 1975;36:1473–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1473::aid-cncr2820360440>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinen K, Kazumoto T, Ohkura Y, Matsubara O, Tsuchiya E. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy caused by a gastric carcinoma expressing vascular endothelial growth factor and tissue factor. Pathol Int. 2005;55:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyano S, Izumi S, Takeda Y, Tokuhara M, Mochizuki M, Matsubara O, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:597–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato Y, Marutsuka K, Asada Y, Yamada M, Setoguchi T, Sumiyoshi A. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy. Pathol Int. 1995;45:436–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keenan NG, Nicholson AG, Oldershaw PJ. Fatal acute pulmonary hypertension caused by pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:e11–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shigematsu H, Andou A, Matsuo K. Pulmonary tumor embolism. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:777–8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a52e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]