Significance

The continuous replenishment of differentiated cells, for example, those constituting the blood, involves proteins that control the generation and function of stem and progenitor cells. Although “master regulators” are implicated in these processes, many questions remain unanswered regarding how their synthesis and activities are regulated. We describe a mechanism that controls the production of the master regulator GATA binding protein-2 (GATA-2) in the context of blood stem and progenitor cells. Thousands of GATA-2 binding sites exist in the genome, and genetic analyses indicate that they differ greatly and unpredictably in functional importance. The parameters involved in endowing sites with functional activity are not established. We describe unique insights into ascertaining functionally important GATA-2 binding sites within chromosomes.

Keywords: cis element, HSCs

Abstract

The unremitting demand to replenish differentiated cells in tissues requires efficient mechanisms to generate and regulate stem and progenitor cells. Although master regulatory transcription factors, including GATA binding protein-2 (GATA-2), have crucial roles in these mechanisms, how such factors are controlled in developmentally dynamic systems is poorly understood. Previously, we described five dispersed Gata2 locus sequences, termed the −77, −3.9, −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 GATA switch sites, which contain evolutionarily conserved GATA motifs occupied by GATA-2 and GATA-1 in hematopoietic precursors and erythroid cells, respectively. Despite common attributes of transcriptional enhancers, targeted deletions of the −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 sites revealed distinct and unpredictable contributions to Gata2 expression and hematopoiesis. Herein, we describe the targeted deletion of the −3.9 site and mechanistically compare the −3.9 site with other GATA switch sites. The −3.9−/− mice were viable and exhibited normal Gata2 expression and steady-state hematopoiesis in the embryo and adult. We established a Gata2 repression/reactivation assay, which revealed unique +9.5 site activity to mediate GATA factor-dependent chromatin structural transitions. Loss-of-function analyses provided evidence for a mechanism in which a mediator of long-range transcriptional control [LIM domain binding 1 (LDB1)] and a chromatin remodeler [Brahma related gene 1 (BRG1)] synergize through the +9.5 site, conferring expression of GATA-2, which is known to promote the genesis and survival of hematopoietic stem cells.

Whereas proximal promoter sequences assemble the basal transcriptional machinery and RNA polymerase, distant cis-regulatory elements often confer tissue-specific or context-dependent transcriptional regulation. Enhancer elements reside many kilobases upstream or downstream of a promoter or within introns, and extensive efforts have focused on elucidating “action-at-a-distance” mechanisms (1). Long-range transcriptional control involves physical interactions between proteins bound at distal regions and promoter sequences and higher order structural transitions, including subnuclear relocalization of target loci (2–4). Given the high frequency of long-range mechanisms at mammalian loci and the mutations that disrupt the function of such elements in pathological conditions, elucidating the underlying mechanisms in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease is critically important. In the context of the essential process of hematopoiesis, we have been dissecting long-range mechanisms controlling the expression and function of the master regulator GATA binding protein-2 (GATA-2) (5–12).

The dual zinc finger transcription factor GATA-2 is expressed in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), select hematopoietic progenitors, endothelial cells, neurons, and additional specialized cell types (13–18). Targeted deletion of Gata2 revealed its essential function for hematopoiesis. Gata2-nullizygous mouse embryos die from severe anemia at embryonic day (E) 10.5 (13, 15), and Gata2+/− HSCs have reduced activity in competitive transplants (19, 20). Heterozygous mutations of GATA2 underlie the development of a human immunodeficiency syndrome, monocytopenia and mycobacterial infection (MonoMAC), and related disorders, which are accompanied by myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia (21–23). Although the critical role of GATA-2 in hematopoietic stem/progenitor biology has been established through rigorous genetic studies, many questions remain unanswered regarding mechanisms underlying Gata2 expression and regulation.

Studies in cultured and primary erythroid cells revealed five GATA-1– and GATA-2–occupied upstream (−77, −3.9, −2.8, and −1.8 kb) and intronic (+9.5 kb) sites of the Gata2 locus (10). Because GATA-2 occupies these prospective regulatory sites in erythroid precursor cells lacking GATA-1, we proposed that this reflects GATA-2–mediated positive autoregulation (10). Because GATA-1 is expressed during erythropoiesis, it displaces GATA-2, instigating Gata2 repression (24). GATA-1–mediated displacement of GATA-2 from chromatin is termed GATA switching, and the GATA factor-occupied sites are deemed GATA switch sites (10, 24).

Despite the compelling biochemical and molecular attributes of the GATA switch sites, targeted deletion of the −1.8 and −2.8 sites individually in the mouse revealed only minor roles in maximizing Gata2 expression in hematopoietic precursors (6, 7). The −1.8−/− and −2.8−/− mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios, and hematopoiesis was largely normal in steady-state and stress contexts. The −1.8 element is uniquely required to maintain, but not to initiate, Gata2 repression in late-stage erythroblasts, but this molecular defect was not coupled to major functional deficits (6). In contrast to the −1.8 and −2.8 site deletions, targeted deletion of the +9.5 intronic site is embryonically lethal at E13.5–E14.5 (5). The +9.5 site is essential for GATA-2 expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and in endothelium during embryogenesis (5, 9, 25, 26). Definitive hematopoiesis is severely impaired in +9.5−/− mice due to defective HSC production, as demonstrated by competitive transplants and imaging of HSC genesis from hemogenic endothelium in the dorsal aorta (25).

The +9.5 site contains an E-box–GATA composite element, which mediates assembly of a complex containing GATA-1 or GATA-2, T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 (TAL1), LIM domain binding 1 (LDB1), and LIM domain only 2 (LMO2). The GATA and E-box motifs, and the spacing between the motifs, are essential for +9.5 site enhancer activity in reporter assays (11). The E-box binding protein TAL1 cooperates with GATA factors in the assembly of a multicomponent complex on E-box–GATA composite elements at genes important for blood cell development and function (27–33). The TAL1-interacting proteins LDB1 and LMO2 control the development and function of HSPCs (22, 34–38). In addition to binding sites containing GATA–E-box composite elements, like the +9.5 site, TAL1 occupies GATA motif-containing sites lacking a consensus E-box, presumably via recruitment by the GATA factor (28). The LIM domain binding-1 coregulator LDB1 promotes chromatin looping (39, 40) and facilitates HSC maintenance, primitive hematopoietic progenitor generation, and erythroid differentiation (37, 41–44). Certain patients with MonoMAC who lack GATA2 coding region mutations harbored deletion or point mutations in or near the +9.5 site (5, 45). Thus, mutations of the +9.5 element, an essential mediator of definitive hematopoiesis in the mouse, underlie human hematopoietic pathology.

The contributions of the −77 and −3.9 GATA switch sites to Gata2 regulation in vivo have not been reported. The −3.9 site harbors two inverted GATA motifs and contains canonical attributes of cis-regulatory elements, including DNase I hypersensitivity and GATA site-dependent enhancer activity in a transfection assay (9, 12). Because these attributes are shared with one or more of the −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 sites, which differ greatly in their importance in vivo, the contribution of the −3.9 site can only be ascertained by disruption of this site at the endogenous locus. Herein, we describe the consequences of a −3.9 site deletion from the endogenous Gata2 locus and a mechanistic comparison of the −3.9 site with the −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 sites in biologically relevant contexts. These studies led to a model to explain the unique importance of the +9.5 site.

Results

Sequence Conservation and Transcription Factor Occupancy Do Not Predict Gata2 Cis-Element Function in Vivo.

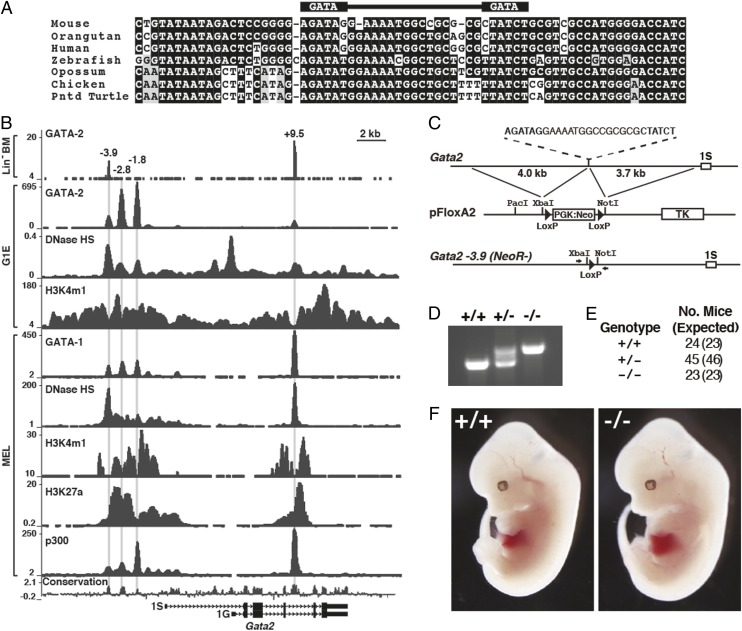

The −3.9 site contains inverted WGATAR motifs that are well conserved among vertebrates (Fig. 1A). GATA-2 occupancy of the −3.9 site, first described in GATA-1–null G1E cells (12), occurs in multiple cell lines and primary cells, including lineage negative (Lin−) hematopoietic progenitors from bone marrow (Fig. 1B). Features commonly associated with enhancers [DNase hypersensitivity, monomethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4, acetylation of H3 at lysine 27, and p300 occupancy (46, 47)] characterize the −3.9 site and other GATA switch sites. To assess −3.9 site function, we deleted 27 nucleotides encompassing the GATA motifs and intervening sequence by homologous recombination and excised the NeoR gene (Fig. 1C). Targeted and WT alleles were distinguishable by PCR with primers flanking the −3.9 site (Fig. 1D). Like −1.8 and −2.8 mice, genotypes of −3.9−/− and −3.9+/− mutants conformed to Mendelian genetics, indicating the −3.9 site is dispensable for viability (Fig. 1E). The −3.9−/− embryos were indistinguishable from WT littermates and did not exhibit hematopoietic or vascular defects characteristic of +9.5−/− embryos (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

The −3.9 GATA switch site bears hallmarks of an important cis-regulatory element. (A) Sequence alignment of the −3.9 site demonstrates conservation among vertebrates. The WGATAR motifs and intervening sequence that were removed by homologous recombination are indicated. (B) ChIP-sequencing profiles for factor occupancy and histone modifications at the Gata2 locus mined from existing datasets (37, 69–72). BM, bone marrow; H3K27a, acetylation of H3 at lysine 27; H3K4m1, monomethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4; MEL, murine erythroleukemia cells. (C) Strategy for targeted deletion of the −3.9 site. Following NeoR excision, the targeted allele has a 126-bp Xba I-to-Not I fragment containing a single LoxP site substituted for the GATA motifs and intervening sequence. Arrowheads indicate positions of primers used for genotype determination. (D) Representative gel shows PCR-based strategy to distinguish WT and targeted alleles following NeoR excision. (E) Genotypes of viable pups from mating −3.9+/− males and females determined at the time of weaning. Expected numbers of pups based on Mendelian ratios are shown in parenthesis. (F) Representative −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− embryos at E12.5.

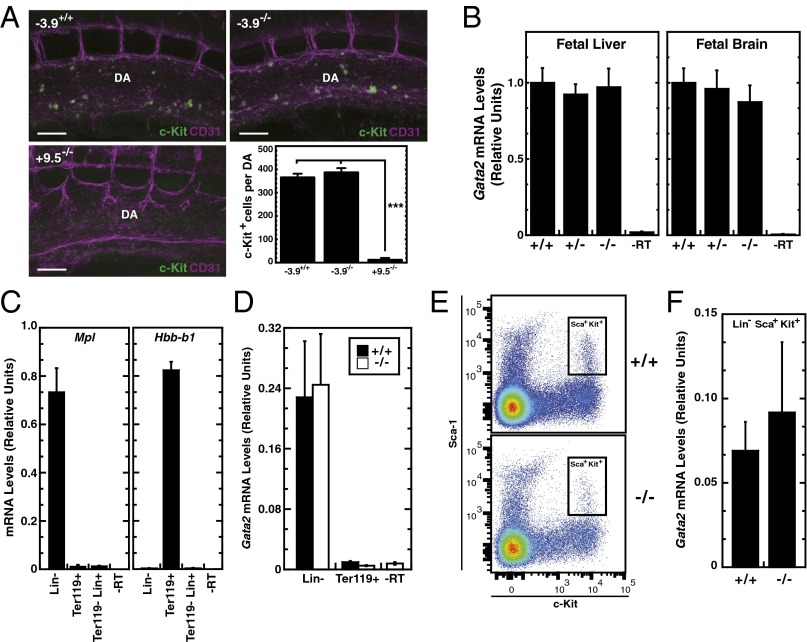

Although a single Gata2 allele is sufficient to confer viability in Gata2+/− and +9.5+/− mouse strains, heterozygosity in these mice reduces Gata2 expression, as well as HSC generation and function (5, 19, 20, 25). To assess the influence of the −3.9 mutation on HSC genesis, we conducted whole-mount 3D embryo imaging to visualize c-Kit+ hematopoietic clusters containing HSCs in E10.5 aorta gonad mesonephros (AGM) of −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− littermates. Whereas +9.5−/− AGM is almost devoid of c-Kit staining (25), −3.9−/− AGM hematopoietic clusters were indistinguishable in size and number vs. those of WT littermates (Fig. 2A). Quantitation of Gata2 mRNA levels in E13.5 fetal livers and brains revealed no differences between −3.9+/+, −3.9+/−, and −3.9−/− littermates (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The −3.9 site is dispensable for Gata2 expression during hematopoiesis. (A) Whole-mount immunostaining of CD31+ cells (magenta) and c-Kit+ cells (green) within the aorta region of E10.5 embryos. The −3.9−/− embryos were compared with WT littermates and with +9.5−/− embryos that almost entirely lack c-Kit+ HSCs (25). (Scale bars, 100 μM.) Quantitation of the number of c-Kit+ cells per dorsal aorta (DA) (four embryos each for −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/−; two embryos for +9.5−/−) (mean ± SEM). (B) Quantitative analysis of Gata2 mRNA in E13.5 livers [six litters: −3.9+/+ (n = 12), −3.9+/− (n = 20), −3.9−/− (n = 18)] and brains [four litters: −3.9+/+ (n = 9), −3.9+/− (n = 14), −3.9−/− (n = 11)] (mean ± SEM). −RT, no reverse transcriptase. (C) Ter119+ and Lin− populations were sequentially isolated from bone marrow via magnetic bead separation. Enrichment of the distinct populations was confirmed in −3.9+/+ bone marrow samples by measuring the expression of the lineage-restricted genes Mpl (Lin−) and Hbb-b1 (Ter119+). (D) Comparison of Gata2 mRNA expression in Lin− and Ter119+ cells from three independent isolations (mean ± SEM). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of Sca-1+ and c-Kit+ double-positive cells from Lin− cells of −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− mice (E) and comparison of Gata2 expression in Lin−Sca+Kit+ cells from two independent biological replicates (mean ± SD) (F) are shown. ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed unpaired Student t test).

In adult −3.9+/+, −3.9+/−, and −3.9−/− mice, complete blood cell count (CBC) measurements were compared at 2 and 6 mo of age (Tables S1 and S2). The quantities of circulating blood cell types were indistinguishable. Because GATA-2 haploinsufficiency increases quiescence and apoptosis in primitive bone marrow cells without changes to circulating blood cells (19), the −3.9 mutation might alter GATA-2 levels in HSPCs without significantly affecting differentiated cell types. Gata2 mRNA levels were quantitated in Lin− progenitors and Ter119+ erythroid cells isolated from bone marrow of −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− mice. The purity of each population was confirmed by quantitating expression of lineage-specific markers Mpl and Hbb-b1 (Fig. 2C). Although highly expressed in the Lin− population, Gata2 expression levels were indistinguishable between −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− mice (Fig. 2D). In Ter119+ cells, Gata2 expression was not greater than in the control lacking reverse transcriptase. Sca-1 and c-Kit double-positive cells were sorted from the Lin− population (Lin−Sca+Kit+) of −3.9+/+ and −3.9−/− bone marrow to enrich for HSPCs (Fig. 2E). Gata2 expression in these cells was not influenced significantly by the −3.9 mutation (Fig. 2F).

Despite certain shared molecular attributes of the −3.9 and +9.5 sites, the conserved GATA motifs of the −3.9 site were dispensable for Gata2 expression in the embryo and adult, steady-state hematopoiesis, and embryogenesis. To elucidate the unique molecular underpinnings of the critical +9.5 site activity, we mechanistically compared the four GATA switch sites (−3.9, −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5) that have been functionally analyzed in vivo.

Requirements for Assembly of an Intronic Enhancer Complex Containing Master Regulators of Hematopoiesis.

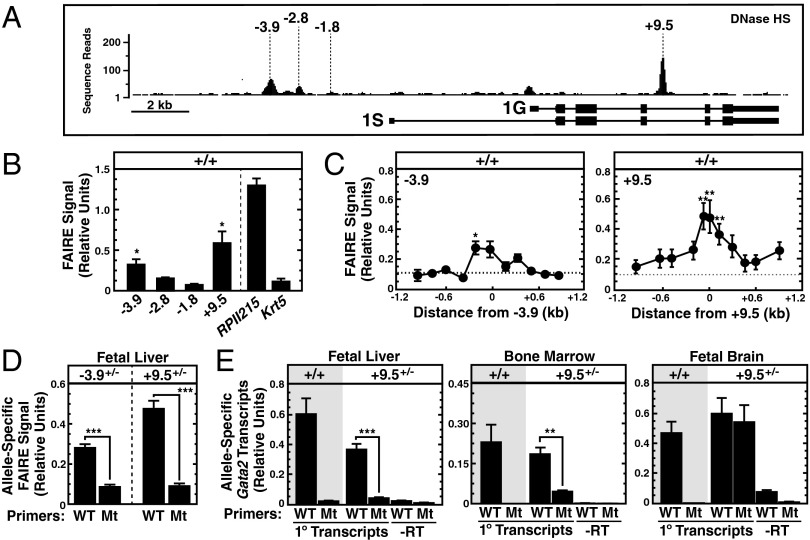

The −3.9 and +9.5 GATA switch sites are DNaseI-hypersensitive in murine erythroleukemia cells (Fig. 1B) and E14.5 fetal liver (48) (Fig. 3A), indicative of an open chromatin configuration. As an alternative approach to evaluate chromatin accessibility at these sites, we conducted formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) analysis (49). Genome-wide analyses indicated that FAIRE peaks overlap with multiple open chromatin parameters, and FAIRE can be conducted with fewer cells than conventional ChIP or DNase I hypersensitivity and/or sensitivity assays (50, 51).

Fig. 3.

GATA switch site mutations abrogate chromatin accessibility at −3.9 and +9.5 sites. (A) DNaseI hypersensitivity at the Gata2 locus in fetal liver mined from mouse Encyclopedia of DNA Elements data (48). (B) Quantitative FAIRE analysis of GATA switch sites in WT fetal liver (n = 4, mean ± SEM). The promoters of the actively transcribed RNA Polymerase II (RPII215) and inactive Keratin 5 (Krt5) genes were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (C) Quantitative FAIRE analysis of chromatin accessibility at and surrounding the −3.9 and +9.5 sites (n = 4, mean ± SEM). The dashed line illustrates the average FAIRE signal at the Krt5 promoter. (D) Allele-specific FAIRE analysis of WT and mutated (Mt) alleles in fetal liver cells from −3.9+/− (n = 4) and +9.5+/− (n = 5) E13.5 embryos (mean ± SEM). Primers used for the allele-specific FAIRE analysis are indicated in Table S3. (E) Allele-specific analysis of Gata2 primary transcripts from WT and Mt alleles in +9.5+/− E13.5 fetal liver and brain (n = 8) and adult bone marrow (n = 3) samples (mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed unpaired Student t test).

FAIRE analysis of E12.5 fetal liver cells demonstrated enhanced accessibility at the −3.9 and +9.5 sites (Fig. 3B), with the open chromatin restricted to the GATA switch sites (Fig. 3C). Allele-specific FAIRE analysis was conducted on −3.9+/− and +9.5+/− E12.5 fetal livers using primers specific for the WT or mutant −3.9 and +9.5 alleles. Chromatin accessibility was considerably reduced at the mutant alleles (Fig. 3D). Despite the reduced accessibility resulting from the −3.9 mutation, Gata2 expression in −3.9−/− fetal livers was indistinguishable from that of −3.9+/+ controls (Fig. 2B). Thus, the −3.9 site confers accessibility at this site but is dispensable for Gata2 expression. Because +9.5−/− mice are deficient in fetal liver HSPCs (5), we took advantage of the intronic location of the +9.5 site to conduct allele-specific measurements of Gata2 primary transcripts generated from WT and mutant alleles in primary cells from +9.5+/− mice. In E12.5 fetal liver and adult bone marrow, transcription of the mutant allele was substantially reduced (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3E), whereas both alleles were expressed equivalently in E12.5 fetal brain (Fig. 3E), consistent with our prior findings (5). In summary, although mutations of the −3.9 and +9.5 sites abrogate local chromatin accessibility, this altered molecular attribute is only linked to loss of Gata2 transcription with the +9.5 site mutation.

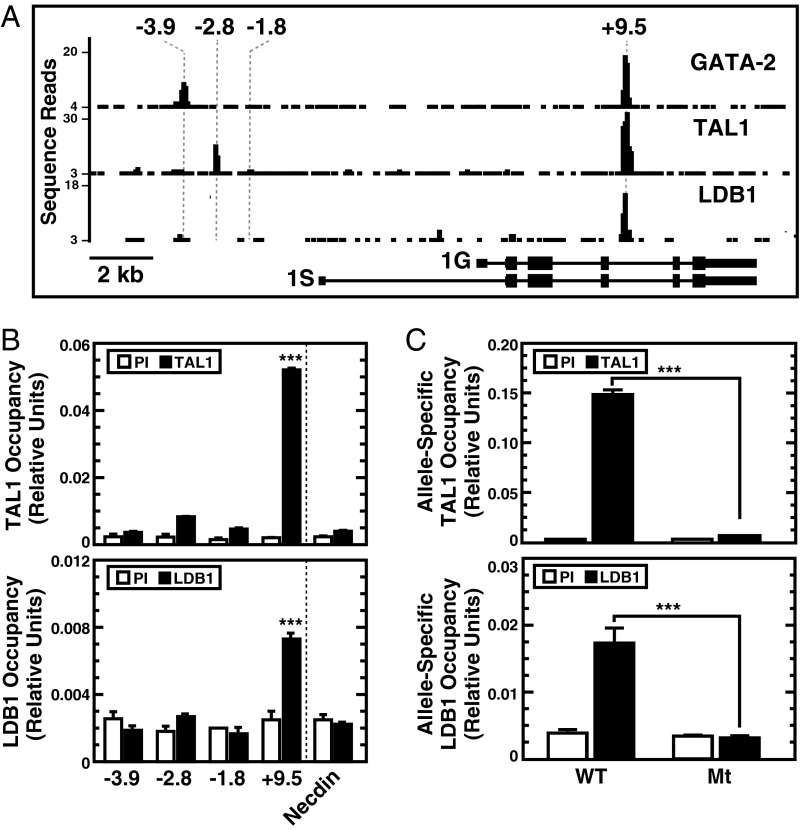

Of the Gata2 GATA switch sites analyzed in vivo, only the +9.5 site contains a conserved E-box in proximity to the GATA motif. GATA-2, TAL1, and LDB1 ChIP-sequencing analysis in Lin− bone marrow (37) revealed the +9.5 site as the sole region of the Gata2 locus occupied by all of these factors (Fig. 4A). Quantitative ChIP analysis in E12.5 fetal liver revealed TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy at the +9.5 site but not at other GATA switch sites (Fig. 4B). The +9.5 site deletion abrogated TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy (P < 0.001) at the mutant, but not WT, alleles in +9.5+/− fetal liver cells (Fig. 4C). The analyses with primary fetal liver cells from +9.5+/− mice described above revealed +9.5 site-dependent chromatin accessibility and regulatory complex assembly at the Gata2 locus.

Fig. 4.

Unique propensity of TAL1 and LDB1 to occupy the +9.5 site. (A) ChIP-sequencing profiles of factor occupancy at the Gata2 locus in lineage-negative bone marrow cells mined from existing datasets (37). (B) Quantitative ChIP analysis of TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy at GATA switch sites of the Gata2 locus in E13.5 fetal liver (n = 3, mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. The Necdin promoter was used as a negative control. (C) Allele-specific ChIP analysis of TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy at WT and Mt alleles in fetal liver from E13.5 +9.5+/− embryos (n = 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed unpaired Student t test). PI, preimmune.

Molecular Attributes That Distinguish the +9.5 Site from Other GATA Switch Sites.

Because targeted deletion of the −3.9, −2.8, or −1.8 site individually did not evoke major biological phenotypes, the +9.5 element uniquely endows hemogenic endothelium of the AGM with the capacity to generate long-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSCs) that populate the fetal liver (5, 25). In addition, the small number of HSCs generated from +9.5−/− AGM undergo apoptosis and lack LT activity, indicating that the +9.5 element also confers LT-HSC survival (25); a similar conclusion emerged from analysis of a conditional Gata2 KO mouse (52). The +9.5 site confers maximal Gata2 expression in the AGM and definitive hematopoietic precursors in the fetal liver (5, 25). A critical question is what molecular attributes underlie the uniquely important +9.5 site activity.

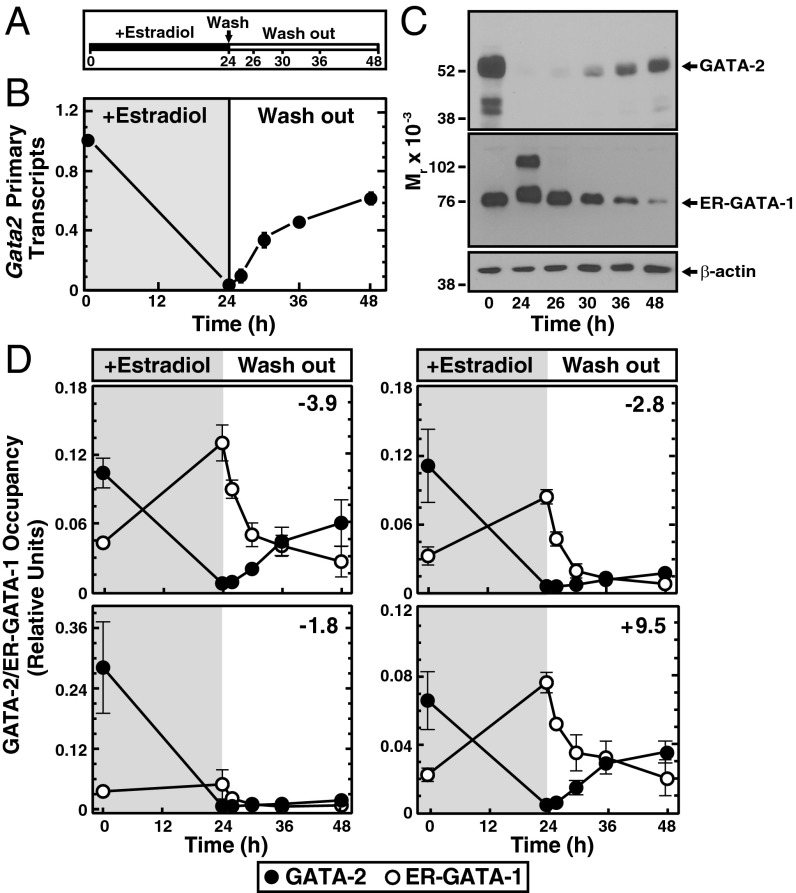

To identify molecular attributes that distinguish the +9.5 site from the other GATA switch sites, we developed a Gata2 repression/reactivation system using GATA-1–null G1E proerythroblast-like cells (53). G1E cells express GATA-2 (53), and ectopic expression of GATA-1 represses GATA-2 and overcomes an erythroid maturation blockade (10, 54). Using a conditionally active GATA-1 allele, in which GATA-1 is fused to the estrogen receptor ligand binding domain (ER–GATA-1), β-estradiol treatment of G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells rapidly induces Gata2 repression (10). We reasoned that removing β-estradiol from the culture media subsequent to Gata2 repression would induce time-dependent loss of ER–GATA-1 activity, ER–GATA-1 dissociation from chromatin, and reversion of ER–GATA-1 influences on gene expression (Fig. 5A). β-Estradiol treatment of G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells for 24 h strongly reduces Gata2 mRNA and protein (10). β-Estradiol washout after 24 h induced reactivation of Gata2 primary transcripts (Fig. 5B) and GATA-2 protein (Fig. 5C), concomitant with reduced ER–GATA-1 levels (Fig. 5C). Because we are unaware of a system that allows one to study the conversion of the repressed Gata2 locus to an active locus, this system has unique utility for elucidating GATA switch site function.

Fig. 5.

Gata2 repression/reactivation assay. Evidence for distinct functional properties of the GATA switch sites is illustrated. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental strategy for Gata2 repression and reactivation in G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells. Treatment of G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells with β-estradiol activates ER–GATA-1, leading to loss of Gata2 transcripts and protein by 24 h (10). Washout of β-estradiol reverses Gata2 repression, leading to restoration of GATA-2 by 48-h treatment. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR was used to measure Gata2 primary transcripts during locus reactivation. After 24 h, β-estradiol treatment (+estradiol) cells were washed in PBS and cultured in media without β-estradiol (washout) for an additional 24 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed before β-estradiol treatment (0 h); after 24 h of β-estradiol treatment; and 2, 6, 12, and 24 h following washout (n = 4, mean ± SEM). (C) Representative Western blots of GATA-2 and ER–GATA-1 from samples isolated at the same times as the corresponding RNA samples. (D) Relative chromatin occupancy of ER-GATA-1 (○) and GATA-2 (●) during Gata2 reactivation using quantitative ChIP (n = 3, mean ± SEM).

GATA-1–mediated Gata2 repression is associated with GATA-1 replacement of GATA-2 at GATA switch sites (10). To investigate the impact of the Gata2 reactivation on the GATA switch, ChIP analysis was used to quantitate changes in ER–GATA-1 and GATA-2 occupancy during Gata2 repression and reactivation (Fig. 5D). As expected (24), 24 h of β-estradiol treatment induced replacement of GATA-2 by ER–GATA-1 at all sites tested, although ER–GATA-1 occupancy of the −1.8 site was low, consistent with our prior findings. Surprisingly, 24 h after washing out β-estradiol, when GATA-2 is readily detected by Western blotting, GATA-2 occupancy was only restored at the +9.5 and −3.9 sites (54% and 57% reoccupancy, respectively), despite loss of GATA-1 from all sites (Fig. 5D).

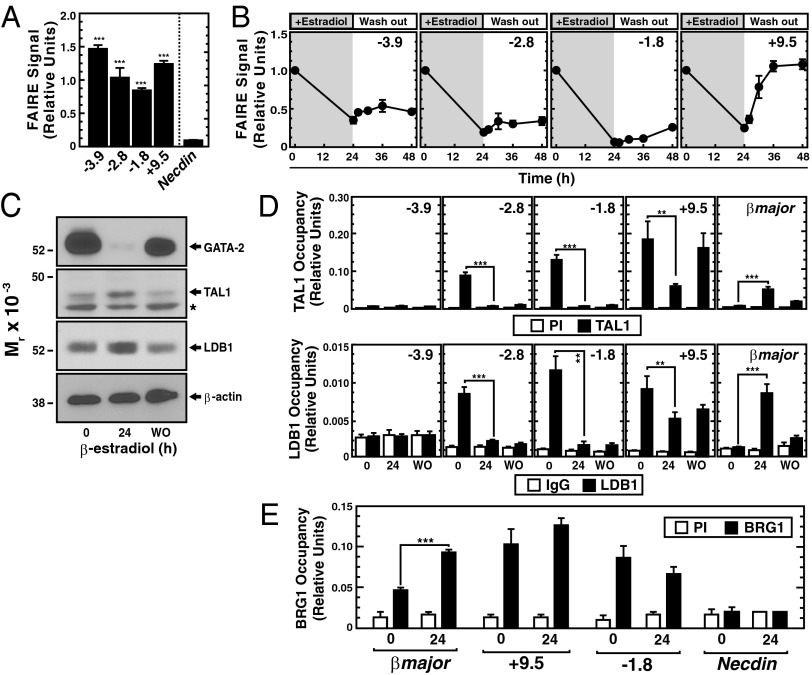

Given that GATA-2 occupies all of the Gata2 GATA switch sites before repression but only reoccupies +9.5 and −3.9 sites following Gata2 reactivation, we tested whether ER–GATA-1–induced repression creates inaccessible chromatin at the −1.8 and −2.8 sites that persists after ER–GATA-1 dissociation from chromatin and prevents subsequent GATA-2 occupancy. We used quantitative FAIRE to analyze chromatin accessibility in the GATA-2 repression/reactivation system. In uninduced proliferating G1E-ER-GATA-1 cells expressing Gata2, chromatin accessibility of the GATA switch sites was significantly greater than in the inactive Necdin promoter (Fig. 6A). ER–GATA-1–mediated GATA-2 displacement reduced FAIRE signals at GATA switch sites 2.8- to 14-fold (Fig. 6B, 24 h). Upon Gata2 reactivation, chromatin accessibility was restored (108% of 0 h) only at the +9.5 site (Fig. 6B, 48 h; P < 0.001); accessibility of −1.8, −2.8, and −3.9 sites remained low (Fig. 6B, 48 h). The unique tripartite chromatin signature of the +9.5 site, in which accessibility is lost upon repression and restored upon reactivation, reflects +9.5 site activity to mediate dynamic chromatin transitions during Gata2 activation. Because this tripartite chromatin signature distinguishes the +9.5 site from other switch sites, we evaluated mechanisms underlying this unique behavior.

Fig. 6.

Molecular attributes of the +9.5 site revealed by the repression/reactivation assay. (A) Quantitative FAIRE analysis of chromatin accessibility at GATA switch sites in untreated G1E-ER-GATA-1 cells (0 h). The inactive Necdin locus was used as a negative control (n = 4, mean ± SEM). (B) Quantitative FAIRE analysis of chromatin accessibility at GATA switch sites upon Gata2 repression and reactivation. FAIRE signals for the 0-h times were normalized to 1.0 (n = 4, mean ± SEM). (C) Representative Western blots of GATA-2, TAL1, and LDB1 protein levels at the same times analyzed by ChIP. The asterisk represents a nonspecific band. (D) Quantitative ChIP analysis of TAL1 and LDB1 chromatin occupancy at the active (0 h), repressed (+24 h), and reactivated (WO) Gata2 locus. The βmajor promoter was used as a positive control (n = 4, mean ± SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (E) Quantitative ChIP analysis of BRG1 chromatin occupancy at the active (0 h) and repressed (+24 h) Gata2 locus and control sites (βmajor and Necdin) (n = 3, mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. WO, washout.

In principle, certain factors might be selectively retained at the +9.5 site, thus explaining its unique capacity to reestablish accessible chromatin. Based on the +9.5 site-restricted TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy in fetal liver (Fig. 4B), we asked whether TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy uniquely characterizes the +9.5 site. Using the repression/reactivation system, we quantitated TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy at the active (0 h, uninduced), repressed (24 h, estradiol-induced), and reactivated (48 h, washout) Gata2 locus. Twenty-four hours after β-estradiol treatment, when GATA-2 protein is undetectable, TAL1 and LDB1 levels were unchanged or increased slightly (Fig. 6C). Both factors occupied the −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 sites of the active Gata2 locus (Fig. 6D). Upon Gata2 repression, TAL1 and LDB1 occupancy decreased at the −2.8 and −1.8 sites but was partially retained at the +9.5 site. Brahma related gene 1 (BRG1) occupied the active and repressed loci (Fig. 6E). The TAL1 and LDB1 levels retained at the +9.5 site were comparable to the highly active βmajor promoter and were considerably higher (P < 0.001) than those at the −1.8 and −2.8 sites (Fig. 6D); ER–GATA-1 is known to increase TAL1 recruitment to the βmajor promoter (40). It is attractive to propose that TAL1/LDB1/BRG1 retention at the +9.5 site of the repressed Gata2 locus reflects a priming mechanism that creates epigenetic memory to ensure a rapid increase in the chromatin accessibility and factor occupancy required for subsequent locus reactivation.

Establishing and Maintaining Physiological GATA-2 Levels: Dual Requirement for a Chromatin Looping Factor and a Chromatin Remodeler.

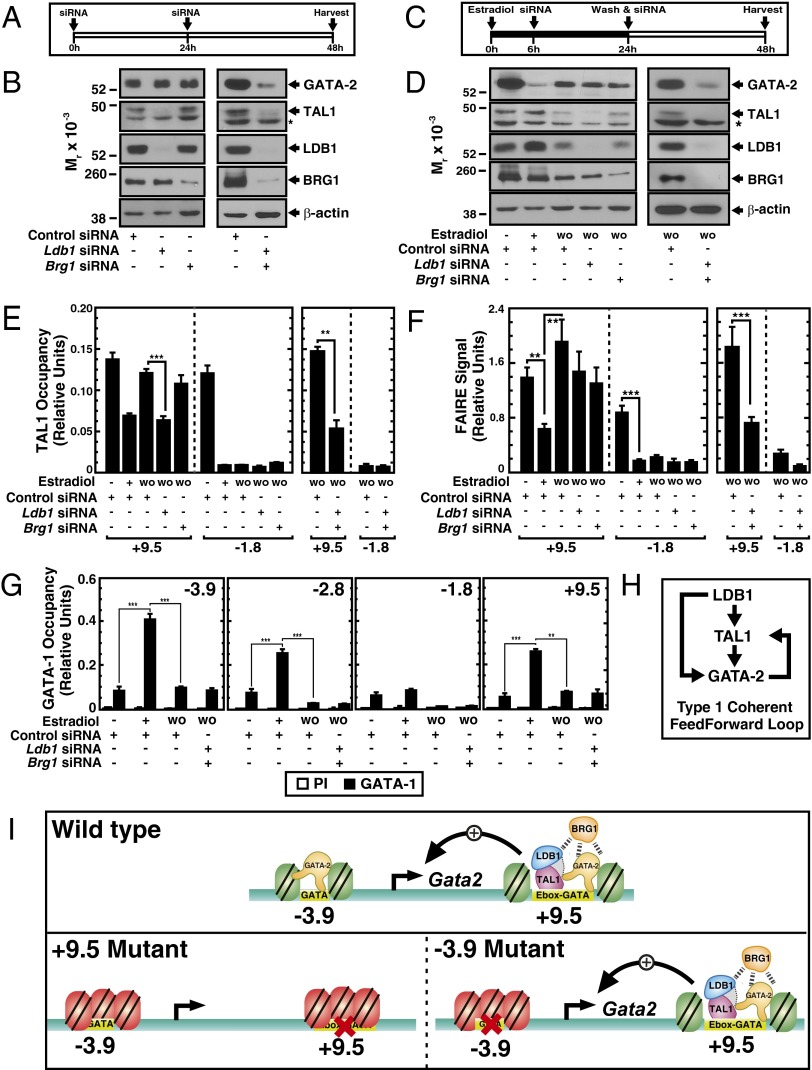

Of the −3.9, −2.8, −1.8, and +9.5 GATA switch sites analyzed in mutant mouse strains, TAL1/LDB1 chromatin occupancy is unique to the +9.5 site. We conducted loss-of-function analyses to establish the importance of the +9.5 site-occupied components. Regarding the possibility of priming the +9.5 site to ensure rapid chromatin remodeling as a requisite step in reactivation, because TAL1 and GATA-1 can localize to chromatin sites with and interact functionally with the ATPase component (BRG1) of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (55–57), BRG1 might mediate chromatin remodeling at the +9.5 site. To assess the contributions of LDB1 and BRG1 to maintenance of Gata2 expression, uninduced G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells were treated twice with siRNA and harvested 24 h after the second treatment (Fig. 7A). When knocked down individually, loss of LDB1 or BRG1 did not influence GATA-2 levels (Fig. 7B), whereas simultaneous loss of LDB1 and BRG1 substantially reduced GATA-2. LDB1 and BRG1 activity to establish Gata2 expression was assessed with the reactivation system (Fig. 7C). Although knocking down LDB1 or BRG1 individually did not prevent Gata2 reactivation, GATA-2 levels were partially reduced (Fig. 7D, Left and Fig. S1). Knocking down LDB1 did not affect GATA-2 chromatin occupancy (Fig. S2). Resembling the results with uninduced cells, knocking down LDB1 and BRG1 simultaneously greatly reduced reactivation (Fig. 7D, Right). Thus, LDB1 and BRG1 establish and maintain GATA-2 expression.

Fig. 7.

Mechanism underlying +9.5 site function. (A) Knockdown strategy. Cells were transfected with siRNA twice with a 24-h interval and harvested 48 h after the first transfection. (B) Representative Western blots of GATA-2, TAL1, LDB1, and BRG1 following knockdown of Ldb1 and Brg1 mRNAs individually or in combination. The asterisk represents a nonspecific band. Schematic representation (C) and Western blots (D) of siRNA-mediated factor knockdown strategy during Gata2 repression/reactivation. G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells were induced with β-estradiol (0 h) and transfected twice with factor-specific or control siRNAs at 6 and 24 h postinduction. β-estradiol was washed out at the time of the second transfection. Protein and RNA samples were collected at 24 and 48 h. −, β-estradiol uninduced at 0 h; +, β-estradiol induced at 24 h; WO, β-estradiol washout. All conditions received specific siRNA or nontargeting control siRNA at same molar concentration. (E) ChIP analysis of TAL1 occupancy at the +9.5 and −1.8 sites quantitated under individual knockdown or LDB1 and BRG1 combined knockdown conditions (n = 4, mean ± SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (F) FAIRE analysis of chromatin accessibility of +9.5 and −1.8 sites following LDB1 and BRG1 individual or LDB1/BRG1 combined knockdown (n = 3, mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (G) ChIP analysis of GATA-1 occupancy at GATA switch sites following LDB1/BRG1 combined knockdown during GATA-2 reactivation (n = 4, mean ± SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (H) Type I coherent feed-forward loop network motif that controls Gata2 expression. (I) Model depicts GATA switch-site chromatin architecture and its relationship to Gata2 expression. The red X indicates that the motif has been deleted.

In uninduced cells and reactivation contexts, the LDB1 knockdown decreased TAL1 levels without a concomitant change in GATA-2 levels (Fig. 7B). This result is consistent with our prior TAL1 knockdown in G1E–ER–GATA-1 cells, which did not alter GATA-2 levels (58). LDB1 occupies the TAL1 locus (37) (Fig. S3), and therefore might directly regulate TAL1 expression. Although individually knocking down LDB1 prevented the restoration of TAL1 occupancy at the +9.5 site to a level commensurate with the active Gata2 locus (Fig. 7E), under these conditions, the washout still restored chromatin accessibility (Fig. 7F). TAL1 occupancy (Fig. 7E) and chromatin accessibility (Fig. 7F) decreased at the −1.8 site upon repression and were not restored upon Gata2 reactivation. Unlike the individual factor knockdowns, the LDB1/BRG1 double knockdown, which blocked Gata2 reactivation, prevented the washout-induced restoration of open chromatin at the +9.5 site (Fig. 7E). Because the washout decreased GATA-1 occupancy at all Gata2 GATA switch sites (Fig. 7G), the inability to reactivate Gata2 when LDB1 and BRG1 levels are limiting cannot be explained by GATA-1 retention. These results suggest that the failure to establish an active enhancer complex at the +9.5 site underlies the reactivation defect.

Discussion

How to distill large chromatin occupancy datasets into functionally critical genomic sites, especially sites distal to genes, represents a formidable problem with far-reaching implications. Our mouse strains lacking GATA switch sites differ grossly in phenotypes and offer a unique opportunity to elucidate mechanisms that endow GATA factor-bound chromatin sites with nonredundant activity in vivo. Despite certain shared molecular attributes of the −3.9 and +9.5 sites, the conserved GATA motifs of the −3.9 site were dispensable for Gata2 expression in the embryo or adult, in steady-state hematopoiesis, and in embryogenesis.

Because the coupling of the E-box and GATA motif and intronic location distinguish the +9.5 site from the −3.9, −2.8, and −1.8 sites, it is attractive to propose that these attributes are important determinants of +9.5 site activity in vivo. In Gata2-expressing fetal liver cells, the +9.5 site resided in open chromatin and assembled a complex containing GATA-2, TAL1, and LDB1 (Fig. 7I). Simultaneous interrogation of the chromatin accessibility of WT and mutant alleles in +9.5+/− fetal liver cells and analyses with the repression/reactivation system revealed that the +9.5 site mediates dynamic chromatin structure transitions. Although ER–GATA-1 converted accessible chromatin at the +9.5 site and other Gata2 GATA switch sites into inaccessible chromatin, concomitant with repression, the washout-induced loss of GATA-1 activity selectively converted +9.5 site-inaccessible chromatin into accessible chromatin. Intriguingly, TAL1 and LDB1 were partially retained at the +9.5 site but not at other Gata2 GATA switch sites, and upon reactivation, chromatin accessibility was only restored at the +9.5 site. These results suggest that TAL1/LDB1 retention creates an epigenetic memory that ensures reassembly of the functional +9.5 site enhancer and Gata2 transcriptional activation. This mechanism may be conceptually similar to the findings that target gene occupancy by certain transcription factors is retained in mitotic chromatin and is associated with more rapid transcriptional activation upon entry into G1 (59, 60).

GATA-1 and GATA-2 occupy the TAL1 locus and loci-encoding components of the TAL1 complex (e.g., the corepressor ETO2) (61, 62). Herein, we demonstrate that TAL1 protein expression is sensitive to LDB1 protein levels. The relationship between LDB1, TAL1, and GATA-2 can be modeled as a coherent type I feed-forward loop (Fig. 7H), which is predicted to require persistently elevated input signals (e.g., those controlling the LDB1 level/activity), although filtering out transiently elevated input signals, to achieve a robust output (e.g., enhanced HSC generation) (63). LDB1 and BRG1 synergistically confer +9.5 site-accessible chromatin, enhancer activity, and Gata2 expression. Although BRG1 was reported to interact functionally with TAL1 (32), we are unaware of examples of a mechanism requiring both BRG1 and LDB1. The BRG1 activity may have broad implications in diverse contexts, because BRG1 is required for Pax6-dependent control of neural fate (38), for Olig2 to establish an oligodendrocyte-specific transcriptional program (64), and for cardiovascular development (65, 66).

In summary, we describe a mechanism that endows a stem cell-generating enhancer element with its unique activity and differentiates it from other GATA factor-bound chromosomal sites that we have rigorously analyzed in vivo. Intrinsic to this mechanism is synergism between a chromatin looping factor and a chromatin remodeler to generate physiological levels of the master hematopoietic regulator GATA-2 (Fig. 7I). In the context of hematopoiesis, it will be particularly instructive to consider whether this mechanism is quite selective for controlling GATA-2 and the GATA-2–dependent genetic network or if it has an impact, more broadly, on the HSPC transcriptome.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Gata2 Δ-3.9 Mutant Mice.

The Gata2 −3.9 site sequence AGATAGGAAAATGGCCGCGCGCTATCT containing the inverted WGATAR motifs was replaced with a LoxP-phosphoglycerate kinase neomycin (neo)-LoxP cassette via homologous recombination. Targeting was confirmed by Southern blotting. Chimeric mice were generated by blastocyst injection, and first filial generation pups were screened for germ-line transmission by PCR. NeoR excision was achieved by mating to CMV-cre strain B6.C-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J mice (Jackson Laboratory). Cre-mediated excision of NeoR in the progeny was confirmed by PCR using primers flanking the targeted sequence. Primer sequences are provided in Table S3.

Analysis of Mouse Embryos and Tissues.

Staged embryos were obtained from timed matings of Gata2 −3.9 heterozygotes. Embryo viability was scored by the presence of a beating heart. E13.5 fetal livers and brains were harvested into TRIzol (Invitrogen) for RNA extraction. For CBC analysis, blood samples from 33 anesthetized mice (four litters: 10 −3.9+/+, 14 −3.9+/−, and 9 −3.9−/− mice) were collected by retroorbital bleeding at 2 and 6 mo of age. CBC measurements were collected using a Hemavet CBC Analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc.). Bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias into PBS containing 2% (vol/vol) FBS and 2 mM EDTA (wash buffer). Dissociated cells were pelleted at 300 × g for 10 min and resuspended in wash buffer at 1 × 108 cells per milliliter. Ter119+ cells were isolated by magnetic bead isolation using rat anti-mouse Ter-119 Biotin (eBioscience). The Ter-119–depleted population was depleted for additional lineage markers using the EasySep Mouse Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Enrichment Kit (Stemcell Technologies). For isolation of Lin−Sca+Kit+ cells, Sca-1 and c-Kit double-positive cells were sorted from Lin− cells on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) using rat anti-mouse CD117 allophycocyanin and anti-mouse Ly-6A/E perdidine chlorophyll protein-Cyaninine5.5 (eBioscience). Data were analyzed using FlowJo v9.0.2 software (TreeStar).

Whole-Embryo Confocal Microscopy.

Embryos were fixed, stained, and analyzed as described (25, 67). Briefly, E10.5 embryos were stained for c-Kit using rat anti-mouse c-Kit (BD Biosciences) and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen) and then for PECAM1 using biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD31 (BD Biosciences) and Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Samples were cleared in a 1:2 mix of benzyl alcohol and benzyl benzoate to increase transparency before imaging with a Nikon A1R Confocal Microscope. Three-dimensional reconstructions were generated from Z-stacks (50–150 optical sections) using Fiji software.

Cell Culture.

G1E-ER-GATA-1 cells (10, 54) were maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 15% FBS (Gemini), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gemini), 2 U/mL erythropoietin, 120 nM monothioglycerol (Sigma), 0.6% conditioned medium from a Kit ligand-producing CHO cell line, and 1 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma). To induce ER–GATA-1, cells were treated with 1 μM β-estradiol. For Gata2 reactivation studies, cells were induced with β-estradiol for 24 h and then washed with 1× Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline to remove β-estradiol. Cells were grown in media without β-estradiol for an additional 24 h, and samples were collected 2, 6, 12, and 24 h after washout. Cell cultures were maintained in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. siRNA-mediated genetic perturbation was used to knock down factors in G1E-ER-GATA-1 cells. Specific SMART Pool siRNAs or nontargeting siRNA pools (240 pmol each; Dharmacon) were transfected into cells using Amaxa nucleofection kit R. For knockdown analyses in uninduced cells, cells were transfected twice with a 24-h interval. For analyses in the reactivation paradigm, two transfections were conducted 6 and 24 h after β-estradiol induction. Samples were harvested at 24 h and/or 48 h.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis.

Total RNA was purified with TRIzol. cDNA was synthesized from 1.5 μg of purified total RNA by Moloney MLV reverse transcriptase (M-MLV RT). Real-time PCR analysis was conducted with SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Control reactions lacking M-MLV RT yielded little to no signal. Relative expression was determined from a standard curve of serial dilutions of cDNA samples, and values were normalized to 18S RNA expression. Primer sequences are provided in Table S3.

Quantitative FAIRE Assay.

FAIRE analysis was conducted as described (50) with minor modifications. Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature and sonicated to shear the DNA to an average size of 200–700 bp. Ten percent of the sonicated chromatin was used as the input control. Following phenol/chloroform extraction, ethanol-precipitated DNA pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of nuclease-free water. For FAIRE analysis of fetal livers, −3.9+/− and +9.5+/− embryos from timed matings were collected at E13.5 into ice-cold PBS. Livers were removed and dissociated by pipetting before formaldehyde fixation. An allele-specific quantitative PCR assay was conducted with allele-specific primers that distinguish WT and mutant alleles. Serial dilutions of input samples were used for generating a standard curve, and relative FAIRE signals were calculated for specific sites.

Western Blot Analysis.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by boiling 1 × 107 cells per milliliter in SDS sample buffer [25 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 3% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 5% glycerol] for 10 min. Samples (10 μL) were resolved by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with specific antibodies. Rabbit anti–GATA-2 (68) and rabbit anti-TAL1 (11) were described previously. Rat anti–GATA-1 (N-6, sc-265), rabbit anti-BRG1 (H-88, sc10768), and goat anti-LDB1 (N18, sc11198) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and mouse anti–β-actin (3700S) was from Cell Signaling.

Quantitative ChIP Assay.

A quantitative ChIP assay was conducted as described previously (8). Cells cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde were sonicated to yield DNA with an average size of 200–700 bp and immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies [rabbit anti–GATA-1 (68), rabbit anti–GATA-2 (68), and rabbit anti-TAL1 (11)], LDB1 (N18, sc11198), and BRG1 (ab110641). For BRG1 ChIP, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 20 min. ChIP samples were quantitated relative to the input DNA using real-time PCR analysis. Rabbit preimmune serum or normal IgG was used as a negative control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant R01 DK68634 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (to E.H.B.), a University of Wisconsin–Madison Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center postdoctoral fellowship (to R.S.), and an NIH T32 Hematology Training Grant Award (to K.J.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1400065111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bender MA, Bulger M, Close J, Groudine M. Beta-globin gene switching and DNase I sensitivity of the endogenous beta-globin locus in mice do not require the locus control region. Mol Cell. 2000;5(2):387–393. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krivega I, Dean A. Enhancer and promoter interactions-long distance calls. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22(2):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harmston N, Lenhard B. Chromatin and epigenetic features of long-range gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(15):7185–7199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HY, Johnson KD, Boyer ME, Bresnick EH. Relocalizing genetic loci into specific subnuclear neighborhoods. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(21):18834–18844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KD, et al. Cis-element mutated in GATA2-dependent immunodeficiency governs hematopoiesis and vascular integrity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3692–3704. doi: 10.1172/JCI61623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snow JW, et al. A single cis element maintains repression of the key developmental regulator Gata2. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9):e1001103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snow JW, et al. Context-dependent function of “GATA switch” sites in vivo. Blood. 2011;117(18):4769–4772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grass JA, et al. Distinct functions of dispersed GATA factor complexes at an endogenous gene locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(19):7056–7067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wozniak RJ, Boyer ME, Grass JA, Lee Y, Bresnick EH. Context-dependent GATA factor function: Combinatorial requirements for transcriptional control in hematopoietic and endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(19):14665–14674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grass JA, et al. GATA-1-dependent transcriptional repression of GATA-2 via disruption of positive autoregulation and domain-wide chromatin remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8811–8816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432147100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wozniak RJ, et al. Molecular hallmarks of endogenous chromatin complexes containing master regulators of hematopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(21):6681–6694. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01061-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martowicz ML, Grass JA, Boyer ME, Guend H, Bresnick EH. Dynamic GATA factor interplay at a multicomponent regulatory region of the GATA-2 locus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(3):1724–1732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai FY, et al. An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature. 1994;371(6494):221–226. doi: 10.1038/371221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minegishi N, et al. The mouse GATA-2 gene is expressed in the para-aortic splanchnopleura and aorta-gonads and mesonephros region. Blood. 1999;93(12):4196–4207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai FY, Orkin SH. Transcription factor GATA-2 is required for proliferation/survival of early hematopoietic cells and mast cell formation, but not for erythroid and myeloid terminal differentiation. Blood. 1997;89(10):3636–3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorfman DM, Wilson DB, Bruns GA, Orkin SH. Human transcription factor GATA-2. Evidence for regulation of preproendothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(2):1279–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardelli J, Thiesson D, Fujiwara Y, Tsai FY, Orkin SH. Expression and genetic interaction of transcription factors GATA-2 and GATA-3 during development of the mouse central nervous system. Dev Biol. 1999;210(2):305–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasen JS, et al. Reciprocal interactions of Pit1 and GATA2 mediate signaling gradient-induced determination of pituitary cell types. Cell. 1999;97(5):587–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues NP, et al. Haploinsufficiency of GATA-2 perturbs adult hematopoietic stem-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2005;106(2):477–484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling KW, et al. GATA-2 plays two functionally distinct roles during the ontogeny of hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200(7):871–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu AP, et al. Mutations in GATA2 are associated with the autosomal dominant and sporadic monocytopenia and mycobacterial infection (MonoMAC) syndrome. Blood. 2011;118(10):2653–2655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansour S, et al. Lymphoedema Research Consortium Emberger syndrome-primary lymphedema with myelodysplasia: Report of seven new cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(9):2287–2296. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hahn CN, et al. Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1012–1017. doi: 10.1038/ng.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bresnick EH, Lee HY, Fujiwara T, Johnson KD, Keles S. GATA switches as developmental drivers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(41):31087–31093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.159079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X, et al. Gata2 cis-element is required for hematopoietic stem cell generation in the mammalian embryo. J Exp Med. 2013;210(13):2833–2842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim KC, et al. Conditional Gata2 inactivation results in HSC loss and lymphatic mispatterning. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3705–3717. doi: 10.1172/JCI61619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tripic T, et al. SCL and associated proteins distinguish active from repressive GATA transcription factor complexes. Blood. 2009;113(10):2191–2201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porcher C, et al. The T cell leukemia oncoprotein SCL/tal-1 is essential for development of all hematopoietic lineages. Cell. 1996;86(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wadman IA, et al. The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/NLI proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16(11):3145–3157. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lécuyer E, et al. The SCL complex regulates c-kit expression in hematopoietic cells through functional interaction with Sp1. Blood. 2002;100(7):2430–2440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahlil R, Lécuyer E, Herblot S, Hoang T. SCL assembles a multifactorial complex that determines glycophorin A expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(4):1439–1452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1439-1452.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Z, Huang S, Chang LS, Agulnick AD, Brandt SJ. Identification of a TAL1 target gene reveals a positive role for the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1 in erythroid gene expression and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(21):7585–7599. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7585-7599.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palii CG, et al. Differential genomic targeting of the transcription factor TAL1 in alternate haematopoietic lineages. EMBO J. 2011;30(3):494–509. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shivdasani RA, Mayer EL, Orkin SH. Absence of blood formation in mice lacking the T-cell leukaemia oncoprotein tal-1/SCL. Nature. 1995;373(6513):432–434. doi: 10.1038/373432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren AJ, et al. The oncogenic cysteine-rich LIM domain protein rbtn2 is essential for erythroid development. Cell. 1994;78(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semerad CL, Mercer EM, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Murre C. E2A proteins maintain the hematopoietic stem cell pool and promote the maturation of myelolymphoid and myeloerythroid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(6):1930–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, et al. Nuclear adaptor Ldb1 regulates a transcriptional program essential for the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(2):129–136. doi: 10.1038/ni.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninkovic J, et al. The BAF complex interacts with Pax6 in adult neural progenitors to establish a neurogenic cross-regulatory transcriptional network. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(4):403–418. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng W, et al. Controlling long-range genomic interactions at a native locus by targeted tethering of a looping factor. Cell. 2012;149(6):1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song SH, Hou C, Dean A. A positive role for NLI/Ldb1 in long-range beta-globin locus control region function. Mol Cell. 2007;28(5):810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mylona A, et al. Genome-wide analysis shows that Ldb1 controls essential hematopoietic genes/pathways in mouse early development and reveals novel players in hematopoiesis. Blood. 2013;121(15):2902–2913. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-467654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, et al. Ldb1-nucleated transcription complexes function as primary mediators of global erythroid gene activation. Blood. 2013;121(22):4575–4585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler E, et al. The genome-wide dynamics of the binding of Ldb1 complexes during erythroid differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24(3):277–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.551810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Love PE, Warzecha C, Li L. Ldb1 complexes: The new master regulators of erythroid gene transcription. Trends Genet. 2014;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu AP, et al. GATA2 haploinsufficiency caused by mutations in a conserved intronic element leads to MonoMAC syndrome. Blood. 2013;121(19):3830–3837, S1–S7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visel A, et al. ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature. 2009;457(7231):854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature07730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernstein BE, et al. ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giresi PG, Kim J, McDaniell RM, Iyer VR, Lieb JD. FAIRE (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 2007;17(6):877–885. doi: 10.1101/gr.5533506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon JM, Giresi PG, Davis IJ, Lieb JD. Using formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) to isolate active regulatory DNA. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(2):256–267. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song L, et al. Open chromatin defined by DNaseI and FAIRE identifies regulatory elements that shape cell-type identity. Genome Res. 2011;21(10):1757–1767. doi: 10.1101/gr.121541.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Pater E, et al. Gata2 is required for HSC generation and survival. J Exp Med. 2013;210(13):2843–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss MJ, Yu C, Orkin SH. Erythroid-cell-specific properties of transcription factor GATA-1 revealed by phenotypic rescue of a gene-targeted cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(3):1642–1651. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregory T, et al. GATA-1 and erythropoietin cooperate to promote erythroid cell survival by regulating bcl-xL expression. Blood. 1999;94(1):87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Z, Meng X, Cai Y, Koury MJ, Brandt SJ. Recruitment of the SWI/SNF protein Brg1 by a multiprotein complex effects transcriptional repression in murine erythroid progenitors. Biochem J. 2006;399(2):297–304. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SI, Bultman SJ, Kiefer CM, Dean A, Bresnick EH. BRG1 requirement for long-range interaction of a locus control region with a downstream promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(7):2259–2264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806420106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu G, et al. Regulation of nucleosome landscape and transcription factor targeting at tissue-specific enhancers by BRG1. Genome Res. 2011;21(10):1650–1658. doi: 10.1101/gr.121145.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fujiwara T, Lee HY, Sanalkumar R, Bresnick EH. Building multifunctionality into a complex containing master regulators of hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(47):20429–20434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007804107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blobel GA, et al. A reconfigured pattern of MLL occupancy within mitotic chromatin promotes rapid transcriptional reactivation following mitotic exit. Mol Cell. 2009;36(6):970–983. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.John S, Workman JL. Bookmarking genes for activation in condensed mitotic chromosomes. Bioessays. 1998;20(4):275–279. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199804)20:4<275::AID-BIES1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujiwara T, et al. Discovering hematopoietic mechanisms through genome-wide analysis of GATA factor chromatin occupancy. Mol Cell. 2009;36(4):667–681. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson NK, et al. Combinatorial transcriptional control in blood stem/progenitor cells: Genome-wide analysis of ten major transcriptional regulators. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(4):532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shoval O, Alon U. SnapShot: Network motifs. Cell. 2010;143(2):326–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu Y, et al. Olig2 targets chromatin remodelers to enhancers to initiate oligodendrocyte differentiation. Cell. 2013;152(1-2):248–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeuchi JK, et al. Chromatin remodelling complex dosage modulates transcription factor function in heart development. Nature Commun. 2011;2:187. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Willis MS, et al. Functional redundancy of SWI/SNF catalytic subunits in maintaining vascular endothelial cells in the adult heart. Circ Res. 2012;111(5):e111–e122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokomizo T, et al. Whole-mount three-dimensional imaging of internally localized immunostained cells within mouse embryos. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):421–431. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Im H, et al. Chromatin domain activation via GATA-1 utilization of a small subset of dispersed GATA motifs within a broad chromosomal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(47):17065–17070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen Y, et al. A map of the cis-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature. 2012;488(7409):116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neph S, et al. An expansive human regulatory lexicon encoded in transcription factor footprints. Nature. 2012;489(7414):83–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trompouki E, et al. Lineage regulators direct BMP and Wnt pathways to cell-specific programs during differentiation and regeneration. Cell. 2011;147(3):577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu W, et al. Dynamics of the epigenetic landscape during erythroid differentiation after GATA1 restoration. Genome Res. 2011;21(10):1659–1671. doi: 10.1101/gr.125088.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.