Abstract

Objective. The objective of this study was to explore patients’ experiences of RA daily life while on modern treatments.

Methods. The methods of this study comprised semi-structured interviews with 15 RA patients, analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

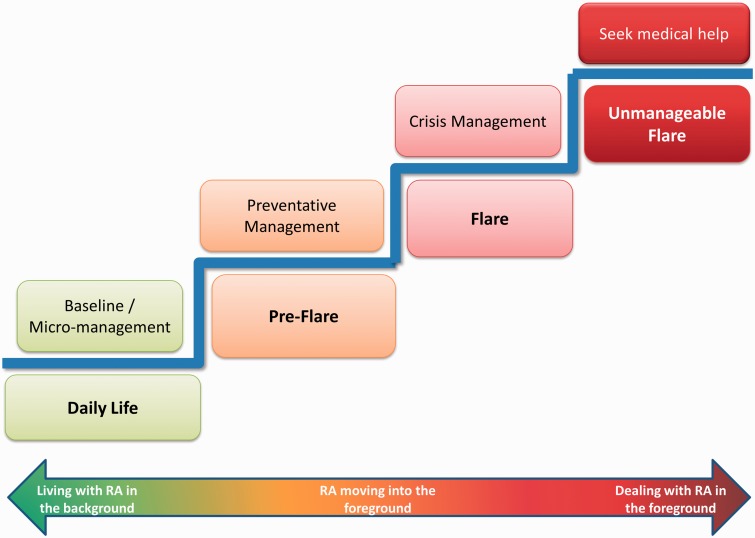

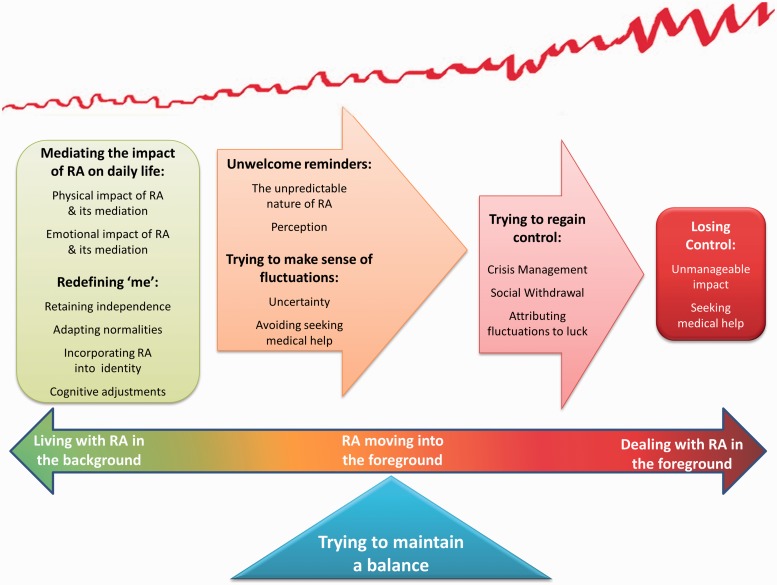

Results. Four themes suggest patients experience life with RA along a continuum from RA in the background to the foreground of their lives, underpinned by constant actions to maintain balance. Living with RA in the background shows patients experience continuous, daily symptoms, which they mediate through micromanagement (mediating the impact of RA on daily life), while learning to incorporate RA into their identity (redefining me). RA moving into the foreground shows patients experience fluctuating symptoms (unwelcome reminders) that may or may not lead to a flare (trying to make sense of fluctuation). Dealing with RA in the foreground shows how patients attempt to manage RA flares (trying to regain control) and decide to seek medical help only after feeling they are losing control. Patients employ a stepped approach to self-management (mediation ladder) as symptoms increase, with seeking medical help often seen as the last resort. Patients seek to find a balance between managing their fluctuating RA and living their daily lives.

Conclusion. Patients move back and forth along a continuum of RA in the background vs the foreground by balancing self-management of symptoms and everyday life. Clinicians need to appreciate that daily micromanagement is needed, even on current treatment regimes. Further research is needed to quantify the level and impact of daily symptoms and identify barriers and facilitators to seeking help.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, daily life, impact, flare, help-seeking, qualitative, interviews

Introduction

RA is a chronic, progressive and systemic autoimmune disease characterized by fluctuating symptoms such as pain and fatigue and unpredictable flares of disease [1, 2]. During the past decade there has been a major change in the use of newer drugs (anti-inflammatory, disease-modifying and biologic agents) that are effective in achieving a response [3, 4]. However, the literature has not explored how RA patients now experience daily life regarding symptoms or impact with no qualitative studies for over 10 years. Previous research has shown that the fluctuation and uncertainty [5] of RA and a non-compliant body [6] can impact on patients’ abilities to continue activities they consider necessary or pleasurable [7], but little is known about whether this impact is reduced as symptoms decrease on modern medication regimes.

A range of self-management and coping strategies are recommended to help patients minimize the impact of RA on their lives [8–10]. However, it is currently not known which strategies patients use, nor how frequently they are used while being treated according to current practice. Disease flares often prompt patients to seek medical help, but how patients distinguish a flare from daily symptom fluctuation, how severe their symptoms must be before they use additional self-management techniques and how long they self-manage before seeking help remain unknown. A recent qualitative study [11] identified that patients are more likely to seek medical help as their self-management strategies increase and their uncertainty as to whether they are in a flare decreases, but not why patients delay, nor their final tipping points for seeking help. The current study aimed to explore how RA patients experience daily life on treatments in current practice (i.e. some, but not all patients on more aggressive treatment regimes, depending on disease severity), how they self-manage their symptoms both in daily life and in flare and how patients decide they are in an RA flare and what the barriers and prompts are for help-seeking.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients attending outpatient clinics with confirmed RA [12] for >2 years (sufficient time for their RA to have settled into a level of daily symptoms normal for them) and who had experienced a self-defined flare (Have you ever experienced a flare?) during their disease were invited by the researcher (C.F.) to participate in semi-structured interviews. Patients from two NHS Trusts in different socio-economic areas and with different methods for accessing help were purposively sampled (using a sampling frame) to reflect a range of age, gender, disease duration, disability and drug treatment. Fifteen of 65 invited patients (23%) agreed to participate. The reasons for declining included being too busy or having recently participated in other research.

Methods

A topic guide (Table 1) based on a literature review and discussions with patient partners (P.R., A.K.) was used to facilitate discussion in the interviews, which followed an iterative process [13], with new concepts emerging during data analysis explored in subsequent interviews.

Table 1.

Interview topic guide

|

A pre-interview questionnaire captured demographic data, disability (HAQ) [14] and patient-perceived disease activity (visual analogue scale). One-to-one semi-structured interviews lasting 45–90 min were conducted by an independent researcher (C.F.) in non-clinical outpatient rooms, digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. New interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. Participants gave informed consent and ethics approval was granted by the Frenchay NHS Research Ethics Committee, (10/H0107/17).

Analysis

Data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis [15], a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data without trying to fit it into a pre-existing coding frame or the researcher’s preconceptions [15]. Thematic analysis is a method in its own right, but not bound to any theoretical framework [15], complementing the pragmatist approach taken here [16]. Pragmatism is guided by the researcher’s desire to produce socially useful knowledge [17] and takes a bottom-up approach, prioritizing methods over epistemology and ontology [18]. Data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s guidelines [15] and managed using NVivo 8 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) [19]. One researcher (C.F.) analysed all transcripts, with two transcripts independently analysed [20, 21] by two researchers (S.H., M.M.) and a patient partner (P.R.), who reached comparable conclusions.

Results

Fifteen patients (12 women) participated [mean age 51.1 years (s.d. 11.8), mean disease duration 14.8 years (s.d. 8.6)] (Table 2). Thematic analysis identified three overarching themes relating to the experience of living with and managing RA (Fig. 1), with an underpinning theme of balance (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Individual interviewees’ demographic and disease-related data (n = 15)

| Patient number | Gender | Age, years | Disease duration, years | HAQ | PtG | Current medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Female | 44 | 23 | 2.75 | 3.8 | Anti-TNF, DMARDs, NSAIDs |

| Participant 2 | Female | 45 | 25 | 2.38 | 4.0 | NSAIDs |

| Participant 3 | Female | 37 | 19 | 0.63 | 2.4 | DMARDs, NSAIDs |

| Participant 4 | Female | 42 | 20 | 1.00 | 3.3 | DMARDs |

| Participant 5 | Male | 48 | 10 | 0.25 | 3.0 | Anti-TNF, DMARDs, steroids |

| Participant 6 | Male | 56 | 13 | 0.25 | 3.5 | Anti-TNF, DMARDs |

| Participant 7 | Female | 67 | 9 | 2.38 | 7.8 | DMARDs |

| Participant 8 | Female | 65 | 16 | 2.75 | 2.8 | Anti-TNF, NSAIDs |

| Participant 9 | Female | 35 | 4 | 1.50 | 1.7 | DMARDs |

| Participant 10 | Female | 51 | 5 | 0.13 | 1.1 | DMARDs |

| Participant 11 | Female | 77 | 30 | n/d | 4.6 | Anti-TNF, DMARDs |

| Participant 12 | Male | 47 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.9 | DMARDs |

| Participant 13 | Female | 59 | 3 | 0.88 | 3.1 | DMARDs |

| Participant 14 | Female | 52 | 23 | 1.88 | 1.9 | DMARDs, NSAIDs |

| Participant 15 | Female | 42 | 17 | 1.75 | 4.8 | DMARDs, steroids |

| Mean | 51.1 | 14.8 | 1.30 | 3.3 | — | |

| s.d. | 11.8 | 8.6 | 1.00 | 1.7 | — | |

| Range | 35–77 | 3–30 | 0–2.75 | 0.9–7.8 | — |

HAQ: 0–3, 3 = severe disability; PtG: patient global element of the DAS, 0–10, 10 = severe disease.

Fig. 1.

Mediation ladder

Fig. 2.

Preliminary fluctuating balances model

Theme 1: living with RA in the background

In normal daily life, patients experience RA as a constant background reality, often being aware of their symptoms. However, to keep their RA in the background, patients describe how they must continually micromanage both their symptoms and their daily lives to accommodate their RA.

(i) ‘It’s not going to get the better of me': the impact of RA on daily life, and its mediation

Even with new treatment regimes, which are deemed more effective, patients experience symptoms such as pain and fatigue in normal daily life:

A normal day, um...trouble getting out of bed really and sort of walking. My feet are very sort of painful and um, but that sort of gradually goes. And then shower and then try and get the kids up and dressed and struggle down the stairs, and then breakfast, take the kids to school, um absolutely exhausted at the end of that. (Participant 1, F, 44, anti-TNF)

Patients experience a number of physical restrictions in their daily life due to their RA symptoms, which they must find ways of overcoming. Some deal with this by carrying on despite their symptoms to maintain their normal lives or by accepting that certain activities will have future consequences:

I just couldn’t be kept in the house so it would still be agony and I would try and drive [demonstrates steering with elbows]. (Participant 2, F, 45)

If I want to go white-water rafting I’ll go white-water rafting and believe me I have. I did pay for it the next day but you know, I enjoyed it at the time. (Participant 3, F, 37)

Other patients find alternative ways to do the things they want to do:

I think even when I’ve had a swollen knee I’ve got on the bike and just pedalled more with one leg than the other. (Participant 4, F, 42)

Even with current, more aggressive treatments, patients feel the need to micromanage their symptoms and activities on a daily basis:

If I was just printing something I will get up and go to the printer I won’t just wait and print a whole load and then go up at one point...because otherwise you do seize up and that causes a lot more pain. (Participant 3, F, 37, DMARDs)

I am conscious not to stay still for too long because if I do that then you feel that when you get up to go then um you find your ability to do that has been sort of kinda reduced. (Participant 5, M, 48, anti-TNF)

You have to look at what sort of activities you are doing and what’s available...it’s all the normal day to day things you have to think about. (Participant 6, M, 56, anti-TNF)

Patients use self-management techniques such as planning and pacing, trying to ensure that they can maintain the equilibrium between life and RA:

I knew that I’d be doing a lot of walking so I made sure that the next day was empty. (Participant 1, F, 44)

RA also has an emotional impact on patients’ daily lives. Many patients reported frustration, anger, worry and guilt associated with their RA:

I do get frustrated, ’cause I’ve always been active. (Participant 7, F, 67)

No room for self-pity at all or anything, no, just anger really. (Participant 5, M, 48)

Patients use a number of strategies to minimize and rationalize this emotional impact. They discussed the importance of support from family (‘Without him [husband] mind, I’d be lost’; Participant 7, F, 67), friends (‘If you go out and you socialize it does take your mind off it’; Participant 8, F, 65), the medical team (‘It’s massive, your relationship with them [medical team]’; Participant 2, F, 45) and other RA patients (‘I didn’t realize how, you know, useful that was, or how nice that was to speak to other people [with RA] sort of in the same age group’; Participant 4, F, 42).

(ii) ‘It’s just a part of me': redefining ‘me’:

Due to the restrictions it imposes on valued and daily activities, RA has the potential to pose a severe threat to patients’ identities. To deal with this, patients begin to accept changes and report the need to ‘learn about your own body again’ (Participant 3, F, 37) and to accept and adjust to a new level of normal:

It’s just the way of life now, you are just used to it. (Participant 6, M, 56)

You just sort of accept it as normal really. (Participant 5, M, 48)

The majority of patients in this study spoke about their RA as though they have incorporated it into their identity:

It’s just part of me. (Participant 1, F, 44)

However, patients are determined not to be defined by their RA and manage to retain their sense of self:

Yeah, it doesn’t define me. (Participant 3, F, 37)

Theme 2: RA moving into the foreground

While patients demonstrated strong coping and self-management strategies that keep their RA in the background of their lives, the unpredictability and uncertainty of RA can mean that despite their best efforts, RA can start to move into the foreground and intrude on their lives.

(i) ‘I forgot that I’ve got this arthritis': unwelcome reminders

Patients discussed their inability to predict what the next day holds due to the unpredictability of RA. They feel unable to predict or they forget what exacerbates their symptoms, leading to an unwelcome reminder that RA is a part of their life:

Some days I can get up in the morning and they’re [swollen joints] gone...and then another day it’s just up like that for nothing. (Participant 7, F, 67)

There doesn’t feel like there’s been any pattern to it. (Participant 9, F, 35)

You might do something if you’re feeling good, you might do something then just go ‘Ooh I shouldn’t have done that’, I forgot that you know, I’ve got this arthritis kind of thing. (Participant 3, F, 37)

Due to unpredictable symptoms many patients find it difficult to make plans, as they may have to be cancelled or altered because of pain, stiffness or fatigue:

I do suffer quite a lot from fatigue, so it really depends how much energy I have to do that and then also if something’s quite sore I might not want to, you know, I might cancel a shopping trip if I’ve got a very sore knee or ankle or something, knowing that it’s going to aggravate it. (Participant 1, F, 44)

RA is also unpredictable in terms of flares. Patients explained that their flares come ‘out of the blue’ (Participant 10, F, 51) and without any warning:

They just come from nowhere. (Participant 6, M, 56)

(ii) ‘It might go away': trying to make sense of fluctuation

While the flare is developing, patients experience a period of uncertainty as to how long the flare will last and even whether it definitely is a flare or not. They try to make sense of what they are experiencing, including attributing the cause:

Whether that’s my immune system being attacked or a, I don’t know, or whether I’ve done too much with that arm in the day or walked too far on the previous day, I don’t know. (Participant 10, F, 51)

I mean they say food don’t give you flare-ups, I believe it do. (Participant 7, F, 67)

Some patients experience a period of wishful thinking:

I am just one of those that thinks it might go away. (Participant 8, F, 65)

Others are aware they need to seek help from the medical team, but continue to avoid help-seeking:

Not wanting to come in here as well, to be fair, ‘cause whenever you come in, you look around and you just think, I’m a generation below, if not two. (Participant 9, F, 35)

I wouldn’t get on the phone straight away because I’m a bit of a, I don’t really want to take drugs to be honest. (Participant 4, F, 42)

Theme 3: dealing with RA in the foreground

As the RA flare takes hold, patients report that their RA can no longer be ignored or pushed into the background and attempt to regain control of their RA and their lives. However, once their self-management strategies can no longer contain their increasing symptoms, patients decide that they have no choice but to seek medical help.

(i) ‘I just try anything': trying to regain control

When patients are in a flare, they can feel like they are losing control and will employ a number of strategies in an attempt to regain that control, including hot and cold packs on swollen or aching joints, resting, pacing and increasing their analgesics or anti-inflammatories:

I would actually sit down and see if I can either rest it or get some ice on it. (Participant 1, F, 44)

I had to make sure that I had enough ‘sick time’ and that, that when I had a flare-up I could take it [sick leave] rather than just overdoing it. (Participant 9, F, 35)

I get out of bed and walk around and I think ‘I’ll go and take diclofenac, or whatever, an aspirin’, whatever I can take. (Participant 10, F, 51)

When they are in a flare, some patients withdraw socially and can also experience apathy and a loss of motivation to do any of the activities they would normally do:

You just go into hibernation mode. (Participant 2, F, 45)

I just feel that I’m not interested in anything really. (Participant 11, F, 77)

Patients increase their self-management strategies, trying to control the flare symptoms, and are more likely to employ crisis management techniques:

I mean I just try anything to, you know, try and defeat it. (Participant 4, F, 42)

If I feel really bad, I do fast for a day. I’ll drink [fluids] but I do fast and that does help. (Participant 2, F, 45)

(ii) ‘It’s like a Game Over’: losing control

Patients describe feelings of frustration and irritation due to the extreme limitations that an RA flare can impose on them, coupled with flare symptoms such as pain and fatigue:

You just put up with it, it’s very very frustrating, extremely frustrating. (Participant 12, M, 47)

As life gets increasingly difficult, patients move on to ask for help from friends or family:

I have to [ask for help] when, I really have to when it’s a flare-up because I can’t pick things up, I can’t even dress myself um, so then I do have to ask for help. (Participant 13, F, 59)

Life becomes severely restricted (‘At times I could not get out of bed’; Participant 11, F, 77) and patients start to lose control of their symptoms. They feel they are fighting a losing battle and eventually have to ask for help:

It isn’t the pain really it’s the immobility, what it makes you feel is, it’s just on top of the restriction you’ve got, it’s like a ‘Game Over’. (Participant 2, F, 45)

Tipping points for seeking help from the medical team include being prompted by a friend or family member, loss of control and recognition that it is different from general symptoms:

I do leave it quite a long time. My daughter and my husband always say ‘You ought to go and see somebody’. (Participant 14, F, 52)

I went into one [flare] and I was in agony and I couldn’t do anything and um, I contacted them. (Participant 15, F, 42)

I think you get a feeling as to what is just general activity and what is the medicine starting not to work and it’s getting a bit more out of control. (Participant 1, F, 44)

Although patients will eventually seek help from the medical team, this is often seen as a last resort:

It’s always the last port of call coming to see the rheumatologist. I go through absolutely everything at home before I come and see them. (Participant 14, F, 52)

Underpinning theme: ‘it’s like a juggling act': trying to maintain a balance

Patients report the need to balance every aspect of their lives to reduce the impact of their RA, perhaps by balancing rest against activity, or independence against seeking help:

It’s sort of a balancing job really. If I use more than my share of energy for one day, it will affect the next. (Participant 1, F, 44)

I think it’s trying to find that happy even isn’t it, between off-loading stuff to other people, yet remaining independent. (Participant 14, F, 52)

In contrast, despite being aware of the importance of maintaining a balance in their daily life, some patients make a deliberate decision to reject the idea of balance after weighing the consequences:

I’m going to have it for the rest of me life so I might as well have the most fun as I can for as long as I can and screw the consequences. (Participant 9, F, 35)

Discussion

Patients reported experiencing a background level of symptoms daily that they must micromanage; life was seen as unpredictable and uncertain due to the fluctuating nature of RA, with a need to maintain a delicate balance in every aspect of their lives to reduce the impact of RA; they delayed seeking medical help for their RA flares, as they employed crisis management techniques.

Even on current more aggressive treatment regimes, which have been deemed more effective [3, 4], this study found that patients are not symptom-free, experiencing at least a baseline level of symptoms daily. For the first time it is revealed that patients being treated according to current practice must micromanage their symptoms, putting adjustments in place throughout their day to reduce their impact (Figs. 1 and 2). Despite advances in treatment, patients still report life with RA as full of uncertainty, as they did 20 years ago [5].

Patients reported the need to retain balance in their lives to reduce the impact of RA (Fig. 2), balancing daily symptoms with self-management techniques and balancing the need to maintain identity and independence through weighing the consequences and making compromises. Patients seemed to reconcile their pre-RA identity with their new identity as a person with RA, either by incorporating RA into their identity or by acknowledging and defining the two identities as separate. This apparent separation of the two aspects of self may be a strategy to maintain normality, a need identified in previous research [22].

While it has been suggested that patients seek help for flares when their self-management increases and their uncertainty regarding a flare decreases [11], this current study reveals an additional stage: decisions to delay. Some patients delay help-seeking, seeing it as a last resort while employing crisis management techniques on top of their other strategies, which has important implications for self-management support and information giving (Fig. 1). However, these barriers and tipping points for seeking help may be different in other settings, e.g. whether the patient sees the general practitioner or rheumatologist, waiting times, distance to the hospital, availability of specialist nurses, cultural backgrounds and free vs private health care.

The current study identified that life with RA fluctuates between RA being in the background and being in the foreground of patients’ lives. The Shifting Perspectives Model [23] suggests that in chronic illness, the need to make sense of their experiences means people continually switch perspective from illness to wellness. However, these data differ significantly in that the fluctuating nature of RA means that it is the individual’s symptoms and their ability to manage them that drives this shift in perspective. Further, people with RA appear to move back and forth along on a continuum from RA being in the background to becoming aware of increasing symptoms to RA being in the foreground rather than experiencing a simple switch from wellness to illness, leading to the preliminary fluctuating balances model (Fig. 2).

This study may have limitations due to sample size, but data saturation was reached by interview 13 [24]. Only three male patients participated (20%), a slightly lower proportion than the usual male/female ratio in RA [25]. This study sampled for a range of drug treatments, whereas two samples of modern vs older treatment would have enabled a qualitative comparison between patients according to their drug treatment. The strengths are that this study sampled for a range of age, disease duration and disability from six consultants across two NHS Trusts, thereby accessing a range of disease experiences and care pathways, and patients were involved in the study design and data interpretation (P.R.).

These data provide important information about life with RA for patients being treated according to current practice. The preliminary fluctuating balances model of symptoms, self-management and decisions for help underpinned by a need for balance provides useful information for clinicians who need to support and facilitate self-management in patients. Further research needs to quantify the level of symptoms still experienced in daily life while on current treatments; to identify whether there are common issues or patients with similar characteristics when defining flare and seeking help (which could be addressed in patient education); and to examine the suitability of the preliminary fluctuating balances model in explaining patients’ experiences of life with RA.

Rheumatology key messages.

Patients constantly employ preventative strategies to micromanage their RA and keep their lives in balance.

Help-seeking is a last resort; RA patients wait until they feel they have lost control.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study; Professor John Kirwan and Dr Paul Creamer, the consultants who facilitated access; Julie Taylor for assisting with recruitment; Angela Knight for her advice as a patient research partner on this project; Dr Jon Pollock for his support as PhD supervisor and Arthritis Research UK for funding this PhD studentship.

Funding: This work was supported by Arthritis Research UK (grant number 18622).

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hill J. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. Rheumatology Nursing: A Creative Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman S, Fitzpatrick R, Revenson TA, et al. London: Routledge; 1995. Understanding Rheumatoid Arthritis. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults and an economic evaluation of their cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1–266. doi: 10.3310/hta10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell LJ, Singh JA. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:234–45. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenström CH, Bergman B, Dahlgren LO. Everyday life with rheumatoid arthritis: a phenomenographic study. Physiother Theory Pract. 1993;9:235–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plach SK, Stevens PE, Moss VA. Corporeality: women’s experiences of a body with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Nurs Res. 2004;13:137–55. doi: 10.1177/1054773803262219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz P, Morris A. Time use patterns among women with rheumatoid arthritis: association with functional limitations and psychological status. Rheumatology. 2007;46:490–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond A. The use of self-management strategies by people with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12:81–7. doi: 10.1177/026921559801200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond A, Freeman K. One-year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of an educational-behavioural joint protection programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2001;40:1044–51. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.9.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luqmani R, Hennell S, Estrach C, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of rheumatoid arthritis (the first two years) Rheumatology. 2006;45:1167–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel215a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewlett S, Sanderson T, May J, et al. ‘I’m hurting, I want to kill myself’: rheumatoid arthritis flare is more than a high joint count—an international patient perspective on flare where medical help is sought. Rheumatology. 2012;51:69–76. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie J, Lewis J. London: Sage; 2003. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishman DB. New York: New York University Press; 1999. The Case for Pragmatic Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedrichs J, Kratochwil F. On acting and knowing: how pragmatism can advance International Relations research and methodology. Int Org. 2009;63:701–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan DL. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1:48–76. [Google Scholar]

- 19.QSR International. Vol. 8. Victoria, Australia: QSR International; 2008. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Doncaster. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guba E, Lincoln Y. Newbury Park, CA: USA: Sage; 1985. Fourth Generation Education. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Adv Nurs Sci. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanderson T, Calnan M, Morris M, et al. Shifting normalities: interactions of changing conceptions of a normal life and the normalisation of symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis. Sociol Health Illn. 2011;33:618–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paterson BL. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:21–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Myasoedova E, et al. The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:633–9. doi: 10.1002/art.30155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]