Abstract

Background

Food store availability may determine the quality of food consumed by residents. Neighborhood racial residential segregation, poverty, and urbanicity independently affect food store availability, but the interactions among them has not been studied.

Purpose

To examine availability of supermarkets, grocery stores, and convenience stores in US census tracts according to neighborhood racial/ethnic composition, poverty, and urbanicity.

Methods

Data from 2000 US Census and 2001 InfoUSA food store data were combined and multivariate negative binomial regression models employed.

Results

As neighborhood poverty increased, supermarket availability decreased and grocery and convenience stores increased, regardless of race/ethnicity. At equal levels of poverty, black census tracts had the fewest supermarkets, white tracts had the most, and integrated tracts were intermediate. Hispanic census tracts had the most grocery stores at all levels of poverty. In rural census tracts, neither racial composition nor level of poverty predicted supermarket availability.

Conclusions

Neighborhood racial composition and neighborhood poverty are independently associated with food store availability. Poor predominantly black neighborhoods face a double jeopardy with the most limited access to quality food and should be prioritized for interventions. These associations are not seen in rural areas which suggest that interventions should not be universal but developed locally.

Keywords: Food store availability, neighborhood, racial residential segregation, concentrated poverty, health disparity

Introduction

Significant racial and ethnic disparities in obesity exist in the United States (US). Age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is 32.4% in non-Hispanic whites, 38.7% among Mexican Americans, and 44.1% in non-Hispanic blacks (Flegal et al., 2010). Reasons for these disparities are uncertain, but one potential factor may be food store availability. Evidence suggests neighborhood racial segregation and poverty affect food store availability, but a search of the literature found only one previous study that has examined this in a nationwide sample (Powell et al., 2007). Additionally, the impact of urbanicity has not been well studied, and there is little data regarding the interaction of these factors affecting neighborhood food store availability.

Studies find positive associations between healthy food availability in neighborhoods and the intake of those foods by residents (Cheadle et al., 1991, Laraia et al., 2004, Larson et al., 2009, Morland and Evenson, 2009). Large supermarkets have been shown to stock more healthy foods (Horowitz et al., 2004) at lower cost (Chung and Meyers, 1999, Cummins and Macintyre, 2002). Grocery and convenience stores are found to stock more energy dense, processed, high-fat, sugary, and salty foods (Walker et al., 2010). Residents of neighborhoods with better access to supermarkets eat healthier diets (Larson et al., 2009), but low-income and minority neighborhoods lack adequate access to large supermarkets (Black and Macinko, 2008, Millstein et al., 2009), a possible result of racial residential segregation.

Racial residential segregation may act indirectly through neighborhood concentrated poverty (Acevedo-Garcia, 2000, Williams, 1996). Studies find neighborhoods with more residents of low socioeconomic status (SES) have fewer high quality food stores and more low quality food stores (Powell et al., 2007, Landrine and Corral, 2009, Moore and Diez Roux, 2006, Morland et al., 2002). However, since racially segregated minority neighborhoods are more likely to be economically disadvantaged (Massey, 2001), it is difficult to disentangle the impact of segregation versus poverty. Zenk et al. (2005b) found no relationship between supermarkets and racial composition in low poverty areas, but in high poverty areas, neighborhoods with the highest percent of black residents were further from a supermarket. This interaction between neighborhood racial composition and neighborhood SES poses a challenge in health disparities research.

The relationship between neighborhood racial composition and food store availability has primarily been studied in urban areas and has consistently found neighborhoods with higher proportions of black residents have fewer supermarkets, longer distances to supermarkets, and more grocery stores (Landrine and Corral, 2009, Zenk et al., 2005b, Baker et al., 2006, Bodor et al., 2010, Galvez et al., 2008, Morland and Filomena, 2007, Zenk et al., 2005a). One study of this relationship in a rural setting found the opposite association; residents of low income and minority communities were closer to all types of food stores compared to high income and white communities (Sharkey et al., 2010).

Our study examines availability of supermarkets, grocery stores, and convenience stores in US census tracts according to neighborhood racial/ethnic composition, poverty, and urbanicity. It expands on an existing nationwide study (Powell et al., 2007) by examining these relationships within census tracts instead of zip codes, examining the interaction between neighborhood racial/ethnic composition and neighborhood income, and including analysis of rural census tracts.

Methods

Data Sources

Census Bureau

Data were obtained from the 2000 US Census Population and Housing Summary Files 1 and 3. The nationwide sample includes 65,174 census tracts. The number of residents per census tract ranges from 1,500 to 8,000 and the spatial composition of census tracts varies widely depending on population density (US Census Bureau, 2012).

InfoUSA

Food store data from 2001 were obtained from InfoUSA, a nationwide commercial database of 12 million US businesses. Data are collected and updated monthly using telephone directories, annual reports, news outlets, government data, and the US Postal Service. Phone verification is conducted for new and large businesses (Brenna Smeall, personal communication, 9/9/10).

Variables

Neighborhoods were measured as census tracts. The dependent variable of interest was a count of (1) supermarkets (2) grocery stores, and (3) convenience stores. InfoUSA provided Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes for each food store. SIC codes are used by the US Department of Labor for industry identification business monitoring. SIC codes 541102 and 541103 identify convenience stores and 541101, 541104–541108 identify supermarkets and grocery stores. Supermarkets were distinguished from grocery stores by classification as a franchise or if the number of store employees was greater than 50. ArcGIS 9.3 software was used to map the latitude/longitude of each food store to its census tract. Each food store type was summed for each census tract to create a count variable for supermarkets, grocery stores, and convenience stores.

The independent variable of interest combined racial/ethnic composition and level of poverty for each census tract. A racial/ethnic composition variable was created categorizing each tract as predominantly non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic if greater than or equal to 60% of the population was of that race/ethnicity, similar to measures used by Moore and colleauges (2008). Remaining tracts were classified as integrated, including those categorized as predominantly Asian or predominantly other. A census tract was define as low poverty if 10% of the households reported an income below the federal poverty level (FPL), medium poverty if 10% to 19.9% of households reported an income below the FPL, and high poverty if greater than or equal to 20% of households reported an income below the FPL. Using the racial/ethnic composition and poverty variables, a combined 12-cateogry predominant neighborhood race/ethnicity and neighborhood poverty variable was created.

Census tracts were defined as urban if they fell within a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and rural if not. The geographic region of each tract was determined by whether it was located in a state in the Census defined Northeast, Midwest, South, or West. Population density was a count of people per square mile of the census tract per 1,000 population.

Analysis

Multivariate count regression models were used to explore associations between food store count and the interaction between racial/ethnic composition and poverty level while controlling for region, population density, and urbanicty. Separate models were run for nationwide, urban, and rural samples. In the rural sample, the number of low and medium poverty tracts that were predominantly black and Hispanic was small (range 2 to 29) so low and medium poverty census tracts were combined.

While Poisson models are typically used with dependent count variables, food store counts were overdispersed; therefore, negative binomial regression models were used (Long, 1997). Separate models were run for each type of food store to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRR). A cluster command was used in all models to account for clustering of census tracts at the county level. Using the IRRs, an estimated count of food stores was generated for all levels of combined neighborhood race/ethnicity and poverty. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0.

Results

Descriptive Summary Statistics

Table 1 presents characteristics of census tracts by neighborhood racial composition. Predominantly white tracts are most frequently low poverty, urban, and in the South. Predominantly black tracts are most frequently high poverty, urban, and in the South. Hispanic tracts are most often high poverty, urban, and in the West. Integrated tracts are most commonly high poverty, urban, and in the West. While 50.1% of white census tracts are low poverty, less than 10% of black or Hispanic tracts are low poverty. Most black and Hispanic census tracts are high poverty, 70.7% and 71.5%, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of United States Census Tract Characteristics, 2000

| Total (%) N=65,174 |

Predominantly White (%) N=45,583 |

Predominantly Black (%) N=5,121 |

Predominantly Hispanic (%) N=3,045 |

Integrated (%) N=11,425 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Poverty | |||||

| Low Poverty | 50.12 | 63.81 | 9.90 | 4.58 | 25.48 |

| Medium Poverty | 28.73 | 28.25 | 19.36 | 23.91 | 36.11 |

| High Poverty | 21.15 | 7.94 | 70.74 | 71.52 | 38.41 |

| Urbanicity | |||||

| MSA | 78.69 | 73.98 | 92.74 | 93.96 | 87.12 |

| non-MSA | 21.31 | 26.02 | 7.26 | 6.04 | 12.88 |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 20.13 | 21.31 | 19.57 | 13.58 | 17.44 |

| Midwest | 25.19 | 29.57 | 28.69 | 6.72 | 11.10 |

| South | 33.48 | 31.30 | 49.91 | 31.53 | 35.34 |

| West | 21.20 | 17.82 | 1.84 | 48.17 | 36.11 |

| Population Density per Sq Mi (mean(SD)) | 5304 (12026) | 2996 (7677) | 10177 (14887) | 16286 (24476) | 9403 (15818) |

On average, there are 1.37 convenience stores, 1.17 grocery stores, and 0.23 supermarkets per tract (Table 2). Urban census tracts have fewer convenience (p<0.001) and grocery stores (p<0.001) and more supermarkets (p<0.001) than rural tracts. As neighborhood poverty increases, there are more grocery stores (p<0.001) and fewer supermarkets per tract (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Summary of Food Store Counts in 65,174 United States Census Tracts, 2001

| Convenience Stores (mean (SD)) | Grocery Stores (mean (SD)) | Supermarkets (mean (SD)) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | 1.37 (1.43) | 1.17 (1.35) | 0.23 (0.51) |

| Urban | 0.89 (1.24) | 0.79 (1.23) | 0.24 (0.51) |

| Rural | 1.66 (1.68)c | 1.32 (1.41)c | 0.22 (0.50) c |

| Low Poverty | 1.21 (1.20)b | 0.76 (0.95)b | 0.26 (0.53)b |

| Medium Poverty | 1.59 (1.56)a | 1.33 (1.35)a | 0.24 (0.52)a |

| High Poverty | 1.38 (1.61)a,b | 1.77 (1.72)a,b | 0.16 (0.42)a,b |

| Predominantly White | 1.10 (1.37)e,f | 0.75 (1.10)e,f | 0.26 (0.53)e,f |

| Predominantly Black | 0.79 (1.25)d,e,f | 1.20 (1.39)d,f | 0.09 (0.32)d,f |

| Predominantly Hispanic | 0.96 (1.50)d,e | 1.79 (1.92)d,e | 0.18 (0.45)d,e |

| Predominantly Integrated | 1.03 (1.45)d,e | 1.14 (1.54)d,e,f | 0.22 (0.49)d,e |

| Predominantly White/Low Poverty | 0.88 (1.17) | 0.53 (0.86) | 0.27 (0.54) |

| Predominantly White/Medium Poverty | 1.51 (1.59) | 1.12 (1.30) | 0.25 (0.53) |

| Predominantly White/High Poverty | 1.42 (1.60) | 1.22 (1.49) | 0.22 (0.50) |

| Predominantly Black/Low Poverty | 0.45 (0.82) | 0.49 (0.76) | 0.16 (0.41) |

| Predominantly Black/ Medium Poverty | 0.65 (1.09) | 0.90 (1.15) | 0.11 (0.34) |

| Predominantly Black/ High Poverty | 0.88 (1.33) | 1.39 (0.96) | 0.08 (0.30) |

| Predominantly Hispanic/Low Poverty | 0.63 (0.96) | 0.69 (1.55) | 0.26 (0.53) |

| Predominantly Hispanic/ Medium Poverty | 0.79 (1.19) | 1.31 (2.02) | 0.23 (0.49) |

| Predominantly Hispanic/ High Poverty | 1.05 (1.61) | 2.04 (2.02) | 0.16 (0.42) |

| Predominantly Integrated/Low Poverty | 0.61 (0.95) | 0.57 (0.99) | 0.27 (0.53) |

| Predominantly Integrated/Medium Poverty | 1.13 (1.48) | 1.18 (1.44) | 0.25 (0.52) |

| Predominantly Integrated/ High Poverty | 1.23 (1.63) | 1.51 (1.81) | 0.17 (0.44) |

significantly different than <10% poverty at p≤0.001

significantly different than 10–19.9% poverty at p≤0.001

significantly different than MSA at p≤0.001

significantly different than predominantly white at p≤0.001

significantly different than predominantly black at p≤0.001

significantly different than predominantly Hispanic at p≤0.01

Regression Results

Nationwide Sample

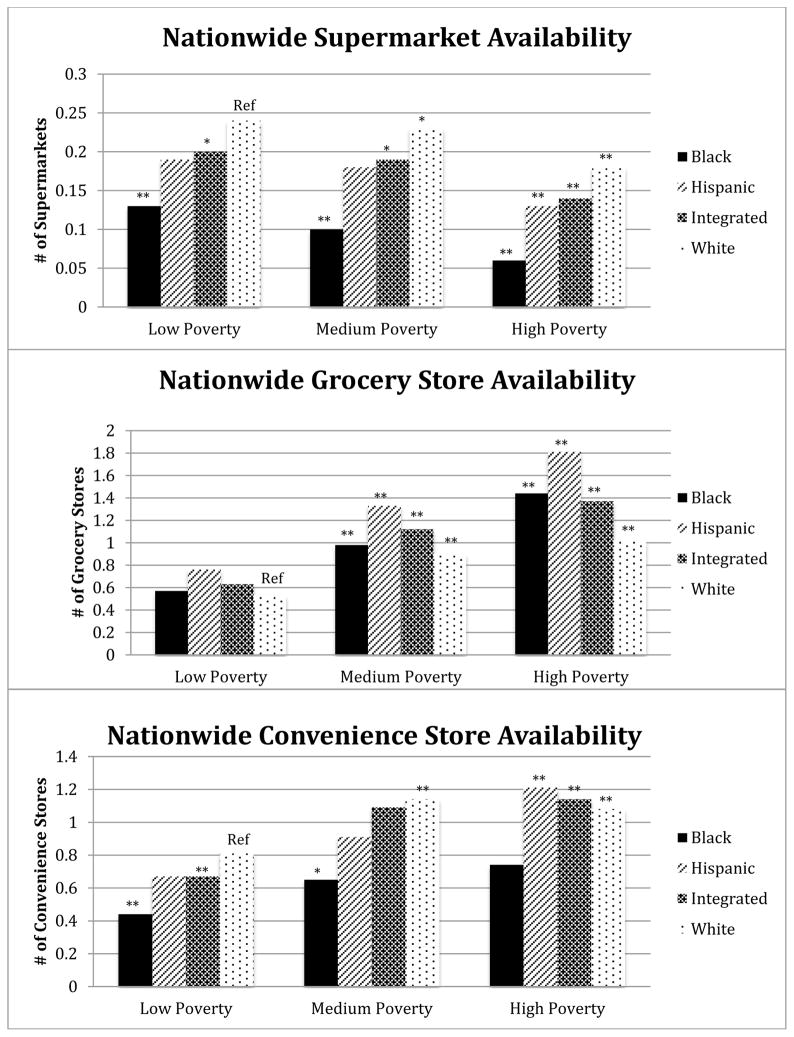

Results from multivariate count regression models (Table 3 and Figure 1) demonstrate that for all neighborhood racial/ethnic groups, the number of supermarkets per census tract decreases in stepwise progression as level of poverty increases. Comparing high poverty tracts, white tracts have the most supermarkets. Compared to predominantly white low poverty tracts, there are fewer (p<0.001) supermarkets in high poverty white (IRR=0.83, 95% CI: 0.76–0.91) followed by integrated (IRR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.57–0.69), Hispanic (IRR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.53–0.69), and black (IRR=0.30, 95% CI: 0.26–0.34) tracts. Compared to other racial/ethnic tracts, predominantly black tracts have the fewest supermarkets at all levels of poverty. The number of supermarkets in predominantly Hispanic low and medium poverty census tracts is lower than in white low poverty tracts, but not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Incidence Rate Ratios for Food Stores in 65,174 nationwide, 51,285 Urban and 13,889 Rural US Census Tracts, 2001

| Nationwide Sample | Urban Sample | Rural Sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience IRR (95% CI) | Grocery IRR (95% CI) | Supermarket IRR (95% CI) | Convenience IRR (95% CI) | Grocery IRR (95% CI) | Supermarket IRR (95% CI) | Convenience IRR (95% CI) | Grocery IRR (95% CI) | Supermarket IRR (95% CI) | |

| Neighborhood Race & Poverty | |||||||||

| Predominantly White/Low Poverty | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Predominantly White/Med Poverty | 1.39 (1.34–1.45)** | 1.68 (0.62–1.75)** | 0.94 (090–0.98)* | 1.52** (1.46–1.59) | 1.79** (1.69–1.89) | 0.93* (0.89–0.98) | 1.23** (1.17–1.29) | 1.39** (1.33–1.46) | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) |

| Predominantly White/High Poverty | 1.33 (1.26–1.42)** | 1.77 (1.67–1.88)** | 0.83 (0.76–0.91)** | 1.49** (1.37–1.61) | 1.77** (1.63–1.93) | 0.75** (0.68–0.84) | 1.19** (1.11–1.27) | 1.60** (1.48–1.72) | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) |

| Predominantly Black/Low Poverty | 0.52 (0.44–0.63)** | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) | 0.59 (0.45–0.77)** | 0.53** (0.44–0.64) | 0.98 (0.84–1.15) | 0.58** (0.44–0.75) | 0.97 (0.68–1.38) | 1.37 (0.75–2.51) | 0.55 (0.23–1.36) |

| Predominantly Black/Med Poverty | 0.78 (0.66–0.92)* | 1.60 (1.40–1.83)** | 0.44 (0.35–0.55)** | 0.77* (0.65–0.92) | 1.69** (2.48–1.93) | 0.43** (0.34–0.54) | |||

| Predominantly Black/High Poverty | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 2.34 (2.14–2.57)** | 0.30 (0.26–0.34)** | 0.84* (0.73–0.95) | 2.52** (2.28–2.79) | 0.25** (0.22–0.29) | 1.39** (1.24–1.57) | 1.76** (1.56–2.00) | 0.77 (0.57–1.05) |

| Predominantly Hispanic/Low Poverty | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) | 0.86 (0.63–1.19) | 0.79 (0.55–1.13) | 1.27 (0.95–1.68) | 0.86 (0.63–1.16) | 1.25 (0.92–1.71) | 1.22 (0.72–2.05) | 0.70 (0.33–1.48) |

| Predominantly Hispanic/Med Poverty | 1.12 (0.91–1.40) | 2.25 (1.91–2.65)** | 0.80 (0.63–1.01) | 1.11 (0.88–1.41) | 2.42** (2.04–2.87) | 0.78* (0.62–0.99) | |||

| Predominantly Hispanic/High Poverty | 1.52 (1.27–1.84)** | 3.13 (2.73–3.57)** | 0.60 (0.53–0.69)** | 1.52** (1.23–1.87) | 3.40** (2.96–3.91) | 0.59** (0.51–0.68) | 1.55** (1.35–1.77) | 1.84** (1.42–2.39) | 0.55* (0.38–0.78) |

| Predominantly Integrated/Low Poverty | 0.80 (0.73–0.87)** | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 0.92 (0.85–0.99)* | 0.82** (0.74–0.89) | 1.10 (0.95–1.26) | 0.90* (0.83–0.98) | 0.50** (0.33–0.75) | 0.77 (0.53–1.10) | 0.85 (0.53–1.35) |

| Predominantly Integrated/Med Poverty | 1.35 (1.24–1.47)** | 1.93 (1.78–2.09)** | 0.87 (0.80–0.96)* | 1.36** (1.23–1.50) | 2.09** (1.90–2.29) | 0.86* (0.78–0.95) | 1.36** (1.23–1.50) | 1.32** (1.19–1.48) | 1.04 (0.83–1.30) |

| Predominantly Integrated/High Poverty | 1.42 (1.32–1.53)** | 2.35 (2.18–2.52)** | 0.63 (0.57–0.69)** | 1.44** (1.31–1.59) | 2.68** (2.46–2.91) | 0.55** (0.49–0.62) | 1.41** (1.31–1.53) | 1.44** (1.32–1.58) | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) |

| Region | |||||||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Midwest | 1.18 (1.08–1.29)** | 0.82 (0.76–0.89)** | 1.18 (1.08–1.28)** | 1.12* (1.00–1.26) | 0.80** (0.72–0.88) | 1.19** (1.08–1.31) | 1.25** (1.16–1.33) | 0.86** (0.79–0.94) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| South | 1.92 (1.75–2.09)** | 1.23 (1.13–1.33)** | 1.60 (1.48–1.74)** | 2.04** (1.83–2.28) | 1.19** (1.08–1.31) | 1.70** (1.55–1.87) | 1.62** (1.51–1.73) | 1.39** (1.27–1.51) | 1.21* (1.03–1.41) |

| West | 0.90 (0.77–1.04) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 1.53 (1.41–1.66)** | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) | 1.06 (0.91–1.25) | 1.56** (1.43–1.72) | 0.91* (0.84–0.99) | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 1.29* (1.09–1.52) |

| Population Density, per 1000 | 0.98 (0.96–0.98)** | 1.01 (1.01–1.01)** | 0.99 (0.98–0.99)* | 0.97** (0.96–0.99) | 1.01** (1.01–1.01) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.88** (0.85–0.90) | 1.23** (1.18–1.28) |

The symbols * and ** represent p≤0.05 and p≤0.001, respectively.

Figure 1.

Count of food stores by neighborhood poverty and racial/ethnic composition in nationwide sample+

The symbols * and ** represent p≤0.05 and p≤0.001, respectively.

+Estimates are incidence rate ratios (IRRs) derived from negative binomial regression models controlling for region, urbanicity, and population density.

For all neighborhood racial/ethnic groups, the number of grocery stores increases in stepwise progression as the level of neighborhood poverty increases. In high poverty white, black, Hispanic, and integrated tracts, there were 1.77 (95% CI: 1.67–1.88), 2.34 (95% CI: 2.14–2.57), 3.13 (95% CI: 2.73–3.57), and 2.35 (95% CI: 2.18–2.25) times as many grocery stores, respectively, as compared to predominantly white low poverty tracts. For all levels of poverty, predominantly Hispanic tracts have the most grocery stores. However, in low poverty tracts the difference between Hispanic tracts and all other racial/ethnic groups is not statistically different when compared to white low poverty tracts.

For all racial/ethnic groups, except predominantly white, the number of convenience stores increases in stepwise progression as the level of neighborhood poverty increases. Predominantly white, Hispanic, and integrated high poverty tracts have significantly more convenience stores than predominantly white low poverty tracts, 1.33 (95% CI: 1.26–1.42), 1.52 (95% CI: 1.27–1.84), and 1.42 (95% CI: 1.32–1.53) times as many respectively. At all levels of poverty, predominantly black tracts have the fewest convenience stores.

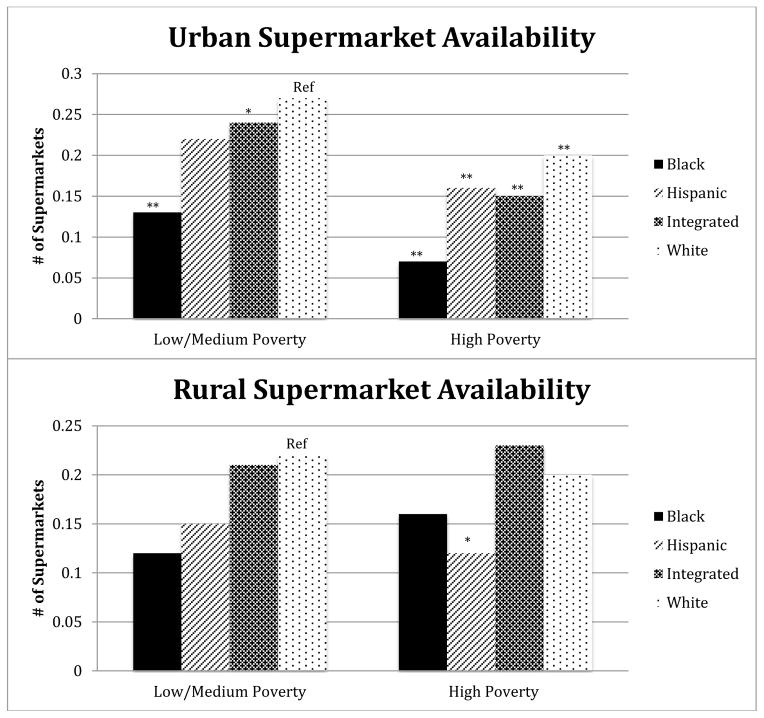

Urban and Rural Samples

Trends in the urban sample are similar to the nationwide sample (Table 3). The rural sample differs from nationwide and urban samples, most notably the availability of supermarkets (Table 3 & Figure 2). The negative association between supermarket availability and neighborhood poverty found in the nationwide and urban samples is not seen in the black and integrated rural tracts. In the rural sample, the difference in supermarket availability is not statistically significant for any race at any poverty level, except high poverty Hispanic tracts (OR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.38–0.78). Similar to urban tracts, predominantly black and Hispanic tracts have the fewest supermarkets in rural tracts. Comparing the magnitude of coefficients, there are more supermarkets in rural versus urban tracts for all types of neighborhoods except Hispanic.

Figure 2.

Count of supermarkets by neighborhood poverty and racial/ethnic composition in rural versus urban samples+

The symbols * and ** represent p≤0.05 and p≤0.001, respectively.

+Estimates are incidence rate ratios (IRRs) derived from negative binomial regression models controlling for region, urbanicity, and population density.

For grocery stores, rural trends remain similar to nationwide and urban samples except there are fewer grocery stores in rural versus urban areas after controlling for population density and geographic region. Trends for convenience store availability are similar in the urban and rural samples except high poverty predominantly black tracts have significantly more convenience stores (p<0.001) than low poverty white tracts, opposite of the urban sample.

Discussion

Disparities in food store availability are each inversely associated with both neighborhood poverty and neighborhood racial segregation, and there is an interaction between them. Neighborhoods with greater poverty and large minority populations have less access to supermarkets. The combination of living in an impoverished and a segregated black neighborhood presents a double disadvantage in access to high quality foods. The distribution of food stores and relationship to segregated Hispanic neighborhoods appears distinct from black neighborhoods and may be a result of socio-cultural differences. Finally, the relationships between neighborhood segregation and poverty are different between urban and rural neighborhoods.

Consistent with previous literature (Powell et al., 2007, Moore and Diez Roux, 2006, Morland et al., 2002, Zenk et al., 2005b, Bodor et al., 2010, Morland and Filomena, 2007), in nationwide and urban samples, at equal levels of poverty, black tracts have the fewest and white tracts have the most supermarkets. Lack of access to healthy foods offered at supermarkets is a likely contributor to racial and ethnic disparities in obesity.

Unlike supermarket availability, grocery store availability is similar in low poverty neighborhoods for all racial/ethnic groups. In high poverty neighborhoods, however, there are strong racial/ethnic differences, presenting a double disadvantage in exposure to low quality foods in poor black neighborhoods.

Hispanic neighborhoods have a distinct pattern of food store availability with the largest number of grocery stores no matter poverty level. Assuming grocery stores stock less healthy foods, this would be detrimental to Hispanic communities. However, there is evidence that grocery store quality in Hispanic neighborhoods is better than in black neighborhoods (Landrine and Corral, 2009). Segregation of ethnic minorities in the US is distinct from segregation suffered by blacks. Immigrant enclaves can provide a shared language, shared culture and social support, while residential segregation of blacks results from historical and ongoing institutional racism (Williams and Collins, 2001). The availability of food stores in Hispanic neighborhoods should be interpreted with caution.

Black census tracts have the fewest convenience stores at all levels of poverty and white tracts have the most. Some previous studies found fewer (Powell et al., 2007, Galvez et al., 2008) convenience stores in predominantly black neighborhoods and others found more (Moore and Diez Roux, 2006, Morland et al., 2002, Morland et al., 2002). Residents of high poverty minority neighborhoods may be less likely to own cars (Gaskin et al., 2012); therefore, less likely to have gas stations with convenience stores. While this might suggest lower consumption of low quality food in black neighborhoods, there is a lack of evidence describing this relationship.

Significant differences in food store availability by poverty level were found in this and previous studies (Powell et al., 2007, Landrine and Corral, 2009, Moore and Diez Roux, 2006, Morland et al., 2002). Across all racial/ethnic neighborhoods, census tracts with the highest levels of neighborhood poverty have the most grocery and convenience stores and the fewest supermarkets. And, the association is incremental, further evidence of the strength and consistency of the relationship between neighborhood poverty and food store availability.

Analysis of the rural sample provides one of the only examining food store availability in a rural setting and offers a unique contribution to the literature. Patterns of supermarket availability differ in urban versus rural areas. Neither neighborhood poverty nor neighborhood racial/ethnic composition is predictive of supermarket availability. And, high poverty black and integrated rural census tracts have more supermarkets than urban tracts.

There are several study limitations. First, neither the existence of food stores nor the quality of food sold in the stores could be validated. Recent research finds that commercial databases provide relatively accurate supermarket and grocery store data but suggest that there is classification bias for convenience stores in urban settings (Han, 2012, Liese, 2013). Therefore, while we feel confident that neighborhoods in this study are accurately characterized by the number of grocery stores and supermarkets, we can not be certain that all supermarkets consistently have available high quality food or that grocery stores consistently lack high quality food. In addition, we cannot be certain that urban neighborhoods in this study have been accurately characterized by the number of convenience stores. With regard to rural census tracts, Gustafson (2012) found that commercial databases were not an adequately accurate characterization of the food environment. Therefore, the food environment of rural neighborhoods in this study could be mischaracterized so results should be interpreted with caution. We suggest more research is needed in rural areas and that ground truthing methods be used to validate the types of stores and quality of food in each store in rural areas (Sharkey & Horell, 2008). A second limitation is the use of census tracts to define neighborhoods to the lack of social meaning (Matthews, 2008). Further, using boundaries set by census tracts limit the measurement of food store availability because there’s no accounting for stores which are located in an adjacent census tract and may be used by nearby residents of a different tract which means that we could be underrepresenting the availability of stores. Additionally, it is not clear how far residents are willing to travel to get their food, relevant shopping areas are thought to be anywhere from 0.5 to 15 miles (Larson et al., 2009), and the variable size of census tracts makes food store availability difficult to compare.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that interventions to promote access to supermarkets should not be applied nationwide. Urban, low-income, segregated communities lack access to supermarkets which likely limits their access to fresh fruit, vegetables, low-fat milk, and high-fiber foods. And, in order to decrease disparities in obesity, these communities should be targeted for innovative policies and interventions. However, interventions should be developed with local knowledge of the food environment so that they build on existing assets and address gaps. There are a variety of creative interventions currently underway around the country. In New York City, grocery stores are encouraged to carry healthy food options (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2010). In Baltimore, residents living in food deserts can order groceries online and have them delivered (Baltimore City Health Department). However, evaluation of innovative interventions needs to be disseminated and interventions should be informed by research that details the complex interactions and influence of social circumstances.

Highlights.

High poverty neighborhoods have fewer supermarkets regardless of race/ethnicity.

At equal poverty levels, black neighborhoods have the fewest supermarkets.

Supermarket availability in urban areas is similar to nationwide.

Rural supermarket availability is not associated with neighborhood poverty.

Rural supermarket availability is not associated with racial/ethnic composition.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (1R01-5R01HL092846-02). A poster presentation of these study findings was awarded the Student Abstract Award by the Epidemiology Section at the 2012 American Public Health Association Annual Conference. Thanks to Larry Wissow, MD, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Gayane Yenokyan, PhD, Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for their support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D. Residential segregation and the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:1143–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Schootman M, Barnidge E, Kelly C. The role of race and poverty in access to foods that enable individuals to adhere to dietary guidelines. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore City Health Department. [Accessed April 28, 2012];Baltimarket: The Virtual Supermarket Project. [Online]. Available: http://www.baltimorehealth.org/virtualsupermarket.html.

- Black JL, Macinko J. Neighborhoods and obesity. Nutrition Reviews. 2008;66:2–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor JN, Rice JC, Farley TA, Swalm CM, Rose D. Disparities in food access: does aggregate availability of key foods from other stores offset the relative lack of supermarkets in African-American neighborhoods? Preventive Medicine. 2010;51:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Curry S, Wagner E, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kristal A. Community-level comparisons between the grocery store environment and individual dietary practices. Prev Med. 1991;20:250–61. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C, Meyers SL. Do the poor pay more for food? An analysis of grocery store availability and food price disparities. The Journal of Consumer Affairs. 1999;33:276–296. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, MacIntyre S. A systematic study of an urban foodscape: The price and availability of food in greater Glasgow. Urban Studies. 2002;39:2115–2130. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez MP, Morland K, Raines C, Kobil J, Siskind J, Godbold J, Brenner B. Race and food store availability in an inner-city neighbourhood. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;11:624–31. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddle GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Services Research. 2012;47:2353–2376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson AA, Lewis S, Wilson C, Jilcott-Pitts S. Validation of food store environment secondary data source and the role of neighborhood deprivation in Appalacia, Kentucky. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:688. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han E, Powell LM, Zenk SN, Rimkus L, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Chaloupka FL. Classification bias in commercial business lists for retail food stores in the US. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9(46) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Colson KA, Hebert PL, Lancaster K. Barriers to buying healthy foods for people with diabetes: Evidence of environmental disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1549–1554. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Corral I. Seperate and unequal: Residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Kaufman JS, Jones JS. Proximity of supermarkets is positively associated with diet quality index for pregnancy. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese AD, Barnes TL, Lamichhane AP, Hibbert JD, Colabianchi N, Lawson A. Characterizing the food retail environment: Impact of county, type, and geospatial error in 2 secondary data sources. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS. Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences Series. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D, editor. Residential segregation and neighborhood conditions in U.S. metropolitan areas. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA. The salience of neighborhood: some lessons learned from sociology. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein RA, Hsin-Chieh Y, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner M, Gary TG. Food availability, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and dietary patterns among blacks with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Medscape Journal of Medicine. 2009;11:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Associations of neighborhood characteristics with the location and type of food stores. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:325–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LV, Diex Roux AV, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, Brines SJ. Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Filomena S. Disparities in the availability of fruits and vegetables between racially segregated urban neighbourhoods. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10:1481–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland KB, Evenson KR. Obesity prevalence and the local food environment. Health & Place. 2009;15:491–5. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and mental Hygiene. [Accessed April 28, 2012];New York City Healthy Bodegas Initiative. 2010 [Online]. Available: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/cdp/healthy-bodegas0rpt2010.pdf.

- Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey JR, Horel S, Dean WR. Neighborhood deprivation, vehicle ownership, and potential spatial access to a variety of fruits and vegetables in a large rural area in Texas. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2010;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. [Accessed January 25 2013];Cartographic Boundary File. 2012 [Online]. Available: http://www.census.gov/geo/www/cob/tr_metadata.html.

- Walter RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health & Place. 2010;16:876–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Introduction: Racism and Health: A Research Agenda. Ethnicity and Disease. 1996;6:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Hollis-Nelly T, Campbell RT, Holmes N, Watkins G, Nwakwo R, Odoms-Young Fruit and vegetable intake in African Americans income and store characteristics. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005a;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Isreal BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. American Journal of Public Health. 2005b;95:660–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]