Abstract

Phlebotomine sandflies were captured in rural settlement and periurban areas of the municipality of Guaraí in the state of Tocantins (TO), an endemic area of American cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL). Forty-three phlebotomine species were identified, nine of which have already been recognised as ACL vectors. Eleven species were recorded for the first time in TO. Nyssomyia whitmani was the most abundant species, followed by Evandromyia bourrouli, Nyssomyia antunesi and Psychodopygus complexus. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index and the evenness index were higher in the rural settlement area than in the periurban area. The evaluation of different ecotopes within the rural area showed the highest frequencies of Ev. bourrouli and Ny. antunesi in chicken coops, whereas Ny. whitmani predominated in this ecotope in the periurban area. In the rural settlement area, Ev. bourrouli was the most frequently captured species in automatic light traps and Ps. complexus was the most prevalent in Shannon trap captures. The rural settlement environment exhibited greater phlebotomine biodiversity than the periurban area. Ps. complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai naturally infected with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis were identified. The data identified Ny. whitmani as a potential ACL vector in the periurban area, whereas Ps. complexus was more prevalent in the rural environment associated with settlements.

Keywords: phlebotomine fauna, Nyssomyia whitmani, Psychodopygus complexus, Leishmania vectors

American cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) has undergone a clear geographical expansion in Brazil in recent decades, which is likely associated with environmental and climatic changes. In the context of this novel distribution, human cases have been recorded in environmentally impacted and deforested rural areas, including periurban regions of some Brazilian towns (MS/SVS 2007).

In most Brazilian endemic areas, ACL is associated with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection , which is transmitted by several sandfly species, including Psychodopygus wellcomei and Psychodopygus complexus , which are involved in the sylvatic cycle in the Amazon Basin, and Nyssomyia whitmani, Nyssomyia intermedia, Nyssomyia neivai and Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei , which are associated with the outskirts of cities and areas that have suffered from environmental impact in the Northeast, Southeast, South and Central Regions (Rangel & Lainson 2009).

In the state of Tocantins (TO), ACL presents an occupational epidemiological profile, affecting mostly males and young adults. In this context, the local transmission patterns are associated with deforestation for the construction of highways, railroads, hydroelectric dams and agricultural expansion, which has favoured the establishment of settlements and villages (Graser 2008, SESAU/TO 2010). A total of 6,497 cases of ACL were recorded in the period from 2001-2012 (Information System for Notifiable Diseases) (dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/index.php).

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the current knowledge of phlebotomine fauna in TO and to identify putative ACL vectors in a rural settlement area and in the periurban environment of Guaraí.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sandfly capture sites - Guaraí is located in the northwestern TO (Supplementary data) at coordinates S08°50'03'' W48°30'37'' and at an altitude of 259 m. The local population is estimated to be 23,445 inhabitants distributed over 2,268,155 km2 with a demographic density of 10.23 inhabitants/km2. The inhabitants' main source of income is agricultural activity (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) (ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/link.php?uf=to). The city lies along the BR-153 highway, which connects the cities of Belém and Brasília, and is the major link between the Central and Northeast Regions of Brazil. The traffic along this highway is heavy, as it constitutes the main conduit of economic activity in the region (Government of the state of Tocantins) (atm-to.org.br/cidade.php?l=e6149e89399dba56fa890afff1b0f138) (to.gov.br/tocantins/guarai/891).

Guaraí is within the Cerrado biome, which has a continuous canopy and tree cover ranging from 50-90%, with the most cover in the rainy season and least during the dry season (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation) (agencia.cnptia.embrapa.br/Agencia16/AG01/arvore/AG01_58_911200585234.html). The sandfly capture sites are referred to as monitoring stations (MSs). In the rural settlement area, the MSs bordered the forests of the Agricultural Project Pedra Branca, MS 1 (S08°40'08'' W48°24'76'') and MS 2 (S08°39'99'' W48°24'73''), approximately 40 km from the town centre (Supplementary data). In the periurban area, two residences were selected, MS 3 (S08°48'55.9” W48°30'25”) and MS 4 (S08°49'09” W48°30'21.6”). These MSs have rural characteristics, such as the presence of animal shelters and a small area with banana plants (Supplementary data).

Sandfly capture and taxonomy - Sandflies were captured from January 2005-June 2008 using CDC light traps (HP model) (Pugedo et al. 2005) and Shannon traps (Sudia & Chamberlain 1962). The light traps were used in peridomestic areas near animal shelters or in the forest every month for three consecutive nights from 06:00 pm-06:00 am. Light traps were placed in each ecotope 1 m above the ground. The captured specimens were fixed in 70% alcohol and identified in accordance with Galati (1995, 2003) ; the abbreviation of the species' names conforms to Marcondes (2007) . Shannon traps were used in MS 1 in a forested part of the rural settlement area over a period of 12 h (06:00 pm-06:00 am) monthly from March-June 2008. The anthropophily of the species was also evaluated in these captures. A single capture with a Shannon trap was made in November 2008 on four consecutive nights to search for natural Leishmania spp infection in phlebotomine females using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The insects were kept alive in nylon cages (Barraud 1929) and were taken to the laboratory (Entomology Laboratory of the Center for Zoonosis Control of Guaraí). For sandfly identification, males and the last abdominal segments of the females were cleared and mounted on slides. Males were identified by analysing the morphology of the genitalia (gonostyle, gonocoxite, structures of the parameres, pump and ejaculatory ducts) as well as the colour of the thighs and thoracic pleurae; the spermathecae, individual ducts and common duct were also observed in females. After identification, the insects were grouped into pools of 10 females and 10 males by species and locality. Male insects were used in diagnostic assays as negative controls. The pools of sandflies were kept at -20°C for DNA extraction.

Statistical analysis - The index of species abundance (ISA) and the standardised index of species abundance (SISA) (Roberts & Hsi 1979) were calculated for the phlebotomine species collected in the rural and periurban MSs. Excel 2010 and Diversidade de Espécies v. 2.0 software (DivEs) were used to analyse the data. The data were entered into Tables organised by MS, species and period of capture. Each column was classified separately according to the number of specimens of each species. The values in each column were ranked, with the highest value classified as 1, the second as 2 and so on. ISA was calculated according to this formula:

ISA = a + Rj/k

where k is the number of columns in the table (number of months of collection), a is the number of columns in which the species was absent multiplied by c, c is the highest value of the ranking obtained in all columns + 1 and Rj is the sum of the values for each species.

The minimum and maximum limits of the index were determined according to the highest distribution classification, where the limit is different in each series of data. To avoid this variation and to standardise the index we used a scale of values between 0-1 to calculate SISA:

SISA = c-ISA/c-1

Species abundance was considered high when the SISA value was close to the maximum value of 1. The results provide information on the relative abundance of species and on the temporal distribution of the collected individuals.

To analyse and compare the overall number of phlebotomine insects captured in the rural and urban areas, the DivEs software was used to analyse the data using the Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H) and the evenness index (J) (Rodrigues 2005).

PCR multiplex studies - To detect Leishmania spp infection, molecular analysis was performed on a total of 250 females and 40 males, which were grouped into pools of 10 specimens each. DNA was extracted as previously described (Pita-Pereira et al. 2005). Multiplex PCR was designed to simultaneously amplify the cacophony gene IVS6 region in Neotropical sandflies, which was used as an internal control for the polymerase enzyme activity and DNA extraction and the conserved kinetoplast DNA minicircle from Leishmania spp. The amplified products were further analysed by dot blot hybridisation with a biotinylated Leishmania ( Viannia )-specific probe (Pita-Pereira et al. 2005). Rigorous procedures were used to prevent contamination: negative control groups (male sandflies) were included in the DNA extraction step, instrument and working areas were decontaminated with diluted chloride solution and ultraviolet light and artificially infected females were added as positive controls.

RESULTS

The Guaraí exhibited diverse phlebotomine fauna with 43 identified species represented in 3,530 total specimens, 1,872 of which were male and of which were 1,658 female (male/female ratio = 1.12:1.0). Eleven phlebotomine species that had never been found in TO were recorded: Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi , Pressatia choti , Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides , Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi , Ps. complexus , Psychodopygus davisi , Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi , Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus , Psychodopygus ayrozai , Psychodopygus paraensis and Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis .

Some species identified in both areas are considered to be putative vectors of leishmaniasis: Nyssomyia antunesi, Ny. whitmani, Ny. intermedia, Bichromomyia flaviscutellata , Ps. complexus, Ps. ayrozai, Ps. paraensis, Ps. hirsutus hirsutus, T. ubiquitalis and Mig. (Mig.) migonei , which are vectors of ACL, and Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis and Mg. (Mig.) migonei , which are vectors of American visceral leishmaniasis (AVL).

The SISA of the Phlebotominae showed that Ny. whitmani was the species with the highest index (0.9524) followed by Evandromyia bourrouli (0.9444), Ny. antunesi (0.9206), Ps. complexus (0.9206) and Lu. longipalpis (0.8571) ( Table I). With regard to species abundance, Ev. bourrouli was the most represented species (1,000) in the rural settlement area, followed by Ny. antunesi (0.9682) and Ps. complexus (0.9206). In the periurban area, Ny. whitmani was the most abundant (1.000), followed by Lu. longipalpis (0.9512) and Ps. complexus (0.878) (Table II).

TABLE I. Index of species abundance (ISA) and standardised index of species abundance (SISA) obtained from the captures with automatic light traps in municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, January 2005-June 2008.

| Species | ISA | SISA | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brumptomyia brumpti | 25.875 | 0.2103 | 25th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi | 28.625 | 0.1230 | 29th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) longipennis | 29.250 | 0.1032 | 34th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer | 31.875 | 0.0198 | 40th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis | 29.500 | 0.0952 | 35th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) villelai | 20.375 | 0.3849 | 17th |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | 12.500 | 0.6349 | 10th |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis a | 5.500 | 0.8571 | 5th |

| Lutzomyia. (Tricholateralis) sherlocki | 30.250 | 0.0714 | 39th |

| Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei a | 15.000 | 0.5556 | 12th |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni | 32.250 | 0.0079 | 41st |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi | 30.250 | 0.0714 | 38th |

| Pressatia choti | 28.250 | 0.1349 | 27th |

| Trichopygomyia dasydopogeton | 14.750 | 0.5635 | 11th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) carmelinoi | 15.625 | 0.5357 | 13th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) lenti | 17.875 | 0.4643 | 16th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) evandroi | 17.000 | 0.4921 | 15th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila | 22.000 | 0.3333 | 20th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walker | 23.625 | 0.2817 | 21st |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | 2.750 | 0.9444 | 2nd |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) pinottii | 20.875 | 0.3690 | 18th |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) begonae | 10.000 | 0.7143 | 8th |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) saulensis | 22.000 | 0.3333 | 19th |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides | 25.000 | 0.2381 | 22nd |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi | 30.250 | 0.0714 | 37th |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana | 29.250 | 0.1032 | 33rd |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) hermanlenti | 25.375 | 0.2262 | 24th |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi | 32.250 | 0.0079 | 43rd |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) shannoni | 28.625 | 0.1230 | 30th |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | 32.250 | 0.0079 | 42nd |

| Viannamyia furcate | 28.750 | 0.1190 | 31st |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | 7.875 | 0.7817 | 7th |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 3.500 | 0.9206 | 4th |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 11.750 | 0.6587 | 9th |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | 26.375 | 0.1944 | 26th |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 6.750 | 0.8175 | 6th |

| Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus a | 28.250 | 0.1349 | 28th |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 15.750 | 0.5317 | 14th |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | 29.625 | 0.0913 | 36th |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 3.500 | 0.9206 | 3rd |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | 2.500 | 0.9524 | 1st |

| Nyssomyia intermedia a | 28.875 | 0.1151 | 32nd |

| Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis a | 25.000 | 0.2381 | 23rd |

a : vector species.

TABLE II. Index of species abundance (ISA) and standardised index of species abundance (SISA) obtained from the captures with automatic light traps for environment in municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, January 2005-June 2008.

| Rural settlement area | Periurban area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | ISA | SISA | Position | ISA | SISA | Position |

| Brumptomyia brumpti | 25.75 | 0.2142 | 25th | 20.50 | 0.0487 | 21th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi | - | - | - | 20.50 | 0.0487 | 23th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) longipennis | 32.00 | 0.0158 | 39th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 26th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer | 31.25 | 0.0396 | 34th | - | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis | - | - | - | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 28th |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) villelai | 24.00 | 0.2698 | 23th | 16.75 | 0.2317 | 17th |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | 14.00 | 0.5873 | 13th | 11.00 | 0.5121 | 8th |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis a | 9.00 | 0.746 | 9th | 2.00 | 0.9512 | 2th |

| Lutzomyia (Tricholateralis) sherlocki | 28.00 | 0.1428 | 30th | - | - | - |

| Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei a | 10.00 | 0.7142 | 10th | 20.00 | 0.0731 | 20th |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni | 32.00 | 0.0158 | 35th | - | - | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi | 28.00 | 0.1428 | 29th | - | - | - |

| Pressatia choti | 24.00 | 0.2698 | 20th | - | - | - |

| Trichopygomyia dasydopogeton | 9.50 | 0.7301 | 9th | 20.00 | 0.0731 | 19th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) carmelinoi | 23.75 | 0.2777 | 19th | 7.50 | 0.6829 | 7th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) lenti | 24.00 | 0.2698 | 22th | 11.75 | 0.4756 | 11th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) evandroi | 21.00 | 0.365 | 18th | 13.00 | 0.4146 | 13th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila | - | - | - | 11.50 | 0.4878 | 10th |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walker | 14.75 | 0.5634 | 14th | - | - | - |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1th | 4.50 | 0.8292 | 4th |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) pinottii | 15.25 | 0.5476 | 15th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 27th |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) begonae | 7.50 | 0.7936 | 7th | 12.50 | 0.439 | 12th |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) saulensis | 17.50 | 0.4761 | 16th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 29th |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides | 28.50 | 0.1269 | 31th | 16.00 | 0.2682 | 16th |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi | 28.00 | 0.1428 | 28th | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana | - | - | - | 20.50 | 0.0487 | 22th |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) hermanlenti | 32.00 | 0.0158 | 38th | 13.25 | 0.4024 | 14th |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi | 32.00 | 0.0158 | 37th | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) shannoni | 30.75 | 0.0555 | 32th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 30th |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | 32.00 | 0.0158 | 36th | - | - | - |

| Viannamyia furcate | 25.00 | 0.238 | 24th | - | - | - |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | 4.50 | 0.8888 | 5th | 11.25 | 0.5 | 9th |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 3.50 | 0.9206 | 3th | 3.50 | 0.878 | 3th |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 9.50 | 0.7301 | 10th | 14.00 | 0.3658 | 15th |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | 26.25 | 0.1984 | 26th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 24th |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 7.00 | 0.8095 | 6th | 6.50 | 0.7317 | 6th |

| Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus a | 24.00 | 0.2698 | 21th | - | - | - |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 11.50 | 0.6666 | 12th | 20.00 | 0.0731 | 18th |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | 26.75 | 0.1825 | 27th | - | - | - |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 2.00 | 0.9682 | 2th | 5.00 | 0.8048 | 5th |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | 4.00 | 0.9047 | 4th | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1th |

| Nyssomyia intermedia a | 31.25 | 0.0396 | 33th | 21.00 | 0.2439 | 25th |

| Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis a | 17.50 | 0.4761 | 17th | - | - | - |

a : vector species.

The H and the J analyses revealed that the indexes recorded in the rural settlement environment (H = 0.9641 and J = 0.6059) were higher than those of the periurban environment (H = 0.7758 and J = 0.5252) (Table III).

TABLE III. Total number, percentage and Shannon-Wiener diversity (H) and evenness (J) indexes of phlebotomines captured in light traps at rural settlement and periurban areas in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, January 2005-June 2008.

| Rural settlement area | Periurban area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | M (n) | F (n) | Total n (%) | M (n) | F (n) | Total n (%) |

| Brumptomyia brumpti | 2 | 2 | 4 (0.16) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi | - | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.10) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) longipennis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.04) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) villelai | 2 | 2 | 4 (0.16) | 4 | 0 | 4 (0.39) |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | 4 | 11 | 15 (0.60) | 6 | 7 | 13 (1.28) |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis a | 53 | 21 | 74 (2.94) | 15 | 42 | 57 (5.62) |

| Lutzomyia (Tricholateralis) sherlocki | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei a | 8 | 10 | 18 (0.72) | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.20) |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.08) | - | - | - |

| Pressatia choti | 0 | 3 | 3 (0.12) | - | - | - |

| Trichopygomyia dasydopogeton | 20 | 32 | 52 (2.07) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.20) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) carmelinoi | 1 | 5 | 6 (0.24) | 8 | 14 | 22 (2.17) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) lenti | 2 | 2 | 4 (0.16) | 7 | 6 | 13 (1.28) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) evandroi | 1 | 4 | 5 (0.20) | 4 | 5 | 9 (0.89) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila | - | - | - | 2 | 10 | 12 (1.18) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walkeri | 4 | 10 | 14 (0.56) | - | - | - |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | 538 | 212 | 750 (29.82) | 83 | 23 | 106 (10.44) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) pinottii | 8 | 0 | 8 (0.32) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) begonae | 0 | 94 | 94 (3.74) | 0 | 8 | 8 (0.79) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) saulensis | 2 | 5 | 7 (0.28) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.10) |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.08) | 3 | 6 | 9 (0.89) |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) hermanlenti | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | 7 | 8 | 15 (1.48) |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) shannoni | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Viannamyia furcata | 0 | 4 | 4 (0.16) | - | - | - |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | 109 | 60 | 169 (6.72) | 7 | 4 | 11 (1.08) |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 47 | 215 | 262 (10.42) | 17 | 78 | 95 (9.36) |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 13 | 50 | 63 (2.50) | 4 | 5 | 9 (0.89) |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | 0 | 9 | 9 (0.36) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.10) |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 11 | 73 | 84 (3.34) | 6 | 23 | 29 (2.86) |

| Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus a | 0 | 4 | 4 (0.16) | - | - | - |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 5 | 16 | 21 (0.83) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.20) |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | 0 | 3 | 3 (0.12) | - | - | - |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 124 | 422 | 546 (21.71) | 11 | 28 | 39 (3.84) |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | 244 | 33 | 277 (11.01) | 478 | 70 | 548 (53.99) |

| Nyssomyia intermedia a | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.04) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.10) |

| Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis a | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.04) | - | - | - |

| Total | 1,202 | 1,313 | 2,515 (100) | 670 | 345 | 1,015 (100) |

| H | 0.9641 | 0.7758 | ||||

| J | 0.6059 | 0.5252 | ||||

a : vector species; F: female; M: male.

In the rural settlement area, 2,515 specimens representing 39 species were captured, 13 of which were found exclusively in this environment: Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer , Lutzomyia (Tricholateralis) sherlocki , Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni , Pi. (Pin.) damascenoi , Pr. choti , Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walkeri , Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi , Pa. (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi , Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla , Viannamyia furcata , Ps. hirsutus hirsutus , Ps. paraensis and T. ubiquitalis . In this environment, Ev. bourrouli had the highest frequency among the collected species (29.82%), followed by Ny. antunesi (21.71%), Ny. whitmani (11.01%) and Ps. complexus (10.42%) (Table III). In the periurban area, 1,015 specimens were collected, belonging to 30 species, four of which were exclusive to this environment, including Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi , Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis, Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila and Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana . Ny. whitmani was the most predominant species, representing more than half of the collected individuals (53.99%), followed by Ev. bourrouli (10.44%) and Ps. complexus (9.36%) (Table III).

When evaluating the overall number of specimens captured per ecotope, it was observed that the MS 2 forested area had the most individuals (n = 848), followed by other environments in which animals were present, such as chicken coops: MS 1 (n = 707), MS 2 (n = 695) and MS 4 (n = 581) (Supplementary data).

The H and the J indexes of the evaluated ecotopes showed the highest values in the banana grove ecotope at MS 4 (H = 1.1238 and J = 0.7063), followed by the forest ecotope at MS 1 (H = 1.0850 and J = 0.6819), the forest ecotope at MS 2 (H = 0.9755 and J = 0.6131) and the chicken coop ecotope at MS 1 (H = 0.9563 and J = 0.6011) (Supplementary data).

The analysis of species frequency per ecotope showed that Ev. bourrouli was present in all ecotopes and predominated in the rural settlement area, as well as in the banana grove ecotope at MS 4 in the periurban area. Ny. antunesi was the predominant species in the rural settlement area chicken coop at MS 2 (42.01%). Ny. whitmani was the most prevalent in the other ecotopes near domestic animal shelters in the periurban area, such as the chicken coop at MS 1 (44.62%), the pig sty at MS 2 (49.52%) and the chicken coop at MS 3 (56.63%), followed by Lu. longipalpis in all ecotopes (Supplementary data).

The Shannon trap captures at the MS1 rural settlement area yielded 1,096 specimens, including 190 males (18%) and 906 (82%) females, resulting in a female/male ratio of 4.55:1.0. Among the 14 species identified, those from the Psychodopygus genus were the most prevalent, including Ps. complexus , Ps. llanosmartinsi and Ps. ayrozai . All of these species were observed biting humans during the captures. Among these species, Ps. comple-xus (42.61%) was predominant (Table IV).

TABLE IV. Number of phlebotomine according to sex, captured monthly in Shannon traps at rural settlement area - monitoring station 1, municipality Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, March-June 2008.

| March | April | May | June | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | M (n) | F (n) | M (n) | F (n) | M (n) | F (n) | M (n) | F (n) | Total n (%) |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (0.09) |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) sherlocki | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.09) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walkeri | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 (0.09) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 (0.09) |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | - | - | - | - | 6 | 2 | - | - | 8 (0.72) |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 3 (0.27) |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 42 | 280 | - | 41 | - | 1 | 7 | 96 | 467 (42.60) |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 21 | 17 | 1 | 3 | - | 2 | 5 | 18 | 67 (6.11) |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | - | 7 | - | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | 11 (1) |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 78 | 165 | - | 60 | - | - | - | 7 | 310 (28.28) |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 19 | 130 | - | 17 | - | - | 1 | 6 | 173 (15.78) |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 (0.18) |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 1 | 8 | - | 1 | 8 | 30 | - | 1 | 49 (4.47) |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 (0.18) |

| Total | 161 | 608 | 1 | 127 | 15 | 37 | 13 | 134 | 1,096 (100) |

a : vector species; F: female; M: male.

A total of 290 specimens were collected and used for PCR and dot blot hybridisation. Sandflies of the same species were analysed in pools of 10; there were 23 Ps. complexus pools (3 male and 20 female pools) and six Ps. ayrozai pools (1 male and 5 female pools) (Table V). The results showed that four of 25 (16%) female pools were positive for Leishmania ( Viannia ) sp. infection. In the Ps. complexus pools, only three of 20 were found to be positive (15%). In the Ps. ayrozai pools (n = 5), one pool (20%) was positive for infection (Supplementary data).

TABLE V. Phlebotomine molecular diagnostic evaluation for infection with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and positive polymerase chain reaction hybridisation results with female pools of Psychodopygus complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai by traps in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil.

| Traps | Ps. complexus (p/n) | Ps. ayrozai (p/n) | Females (p/n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDC light - HP model | 1/52 | 0/0 | 2/5 |

| Shannon | 2/151 | 1/51 | 2/20 |

| Total | 3/203 | 1/51 | 4/25 |

the numbers in superscript represent the groups of females positive related to each species of phlebotomine. n: total number of females evaluated; p: number of positive females.

The municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil.

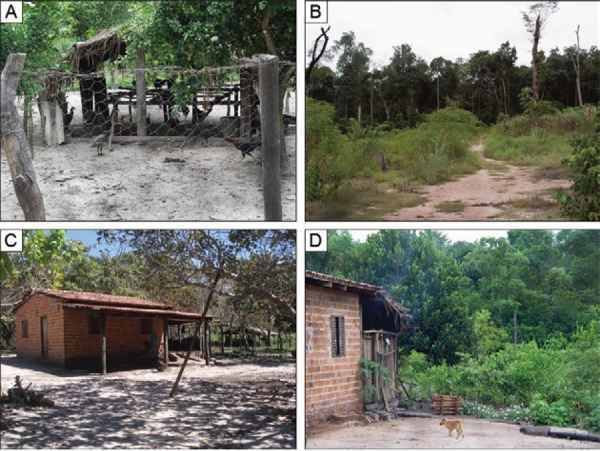

Monitoring stations (MS) in rural settlement area, Agricultural Project Pedra Branca, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 1; C, D: MS 2.

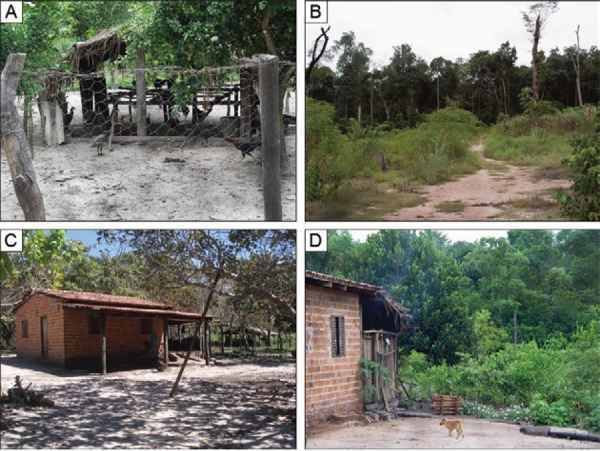

Monitoring stations (MS) in periurban area, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 3; C, D: MS 4.

Products from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplex assays submitted to hybridisation analysis for the diagnosis of naturally Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in Psychodopygus complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai collected in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A: ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel revealing the 220 bp product form the cacophony gene amplification and the 120 bp fragment corresponding to the conserved region of kinetoplast minicircles from Leishmania spp [M: molecular weight marker (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 1: amplification reaction without added DNA (PCR negative control); 2-4: negative controls for the DNA extraction step (male insect pools): 5-8: female sandfly pools (5-7: Ps. complexus positive pools; 8 : Ps. ayrozai positive pool); 9: PCR positive control (DNA extracted from a mixture of male insect pool containing L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes)]; B: dot hybridisation using a biotinylated probe specific for parasites from the Viannia subgenus.

DISCUSSION

Initial studies of phlebotomine fauna in TO focused on the description of species (Barreto 1946, Martins et al. 1962, 1964, 1975); further entomological studies identified 32 sandfly species in the state (Lustosa et al. 1968, Andrade Filho et al. 2001), including the new species Micropygomyia (Silvamyia) echinatopharynx and Martinsmyia reginae (Andrade Filho et al. 2004, Carvalho et al. 2010). These findings indicate a great diversity of sandfly species in TO. Recent investigations of ACL and AVL vectors in rhe municipality of Porto Nacional recorded 48 sandfly species, 22 of which were the first records of these species in the state (Vilela et al. 2011).

The present study identified 43 phlebotomine species in Guaraí, 11 of which were newly recorded species, underscoring the rich biodiversity of the Brazilian Cerrado . Among the identified sandfly species, Ev. bourrouli was predominant in the rural settlement area and presented the second highest percentage in the periurban area. This species was found in various environments and ecotopes, such as preserved forest and animal shelters (chicken coops and pig sties), which underscores its eclectic behaviour. In previous studies carried out in TO, this species was the most frequent at Porto Nacional along with Evandromyia sallesi (Andrade Filho et al. 2001). However, it is important to emphasise that this species has not been reported to transmit pathogens to humans.

Of the species identified in this study, 11 were recorded in TO for the first time, including Ps. complexus , Ps. davisi , Ps. hirsutus hirsutus , Ps. ayrozai , Ps. paraensis and T. ubiquitalis , which are putative ACL vectors in Brazil; other sandfly vectors of leishmaniasis that had already been recorded in TO were also found in Guaraí, including Ny. antunesi, Nyssomyia flaviscutellata, Ny. whitmani, Ny. intermedia, Mig. (Mig.) migonei and Lu. longipalpis .

Previous studies developed in TO identified Ny. whitmani as the main vector of L. (V.) braziliensis , especially in areas affected by hydroelectric construction and agricultural activities, where this sandfly has been found inside and outside residences, near animal shelters and even within forest boundaries (Carvalho 2008, Vilela et al. 2008, 2011). Ny. whitmani is associated with the transmission of L. (V.) braziliensis in most Brazilian endemic areas, occupying different types of plant cover and modified environments (da Costa et al. 2007, Rangel 2010).

Ny. whitmani was the most abundant species among the species collected in the present study. Furthermore, it was the most abundant ACL vector in periurban areas and one of the most represented species in the rural settlement areas. This species was found in all ecotopes, with a particularly high density in animal shelters (chicken coops and pig stys) from residences in the periurban environment. Studies performed in Porto Nacional discussed the capacity of Ny. whitmani to adapt to environmental changes by expanding its transmission cycle (Vilela et al. 2011 ).

Of the ACL vectors observed in Guaraí, it is important to highlight the identification of Ps. complexus , an important L. (V.) braziliensis vector in the low-altitude forests of the state of Pará (PA) in the Amazon Region of northern Brazil (Souza et al. 1996, Lainson & Shaw 2005, Garcez et al. 2009, Rangel & Lainson 2009). This sandfly species has been recorded outside of the Amazon Region, but there has been no evidence to suggest its involvement in L. (V.) braziliensis transmission in the states of Pernambuco (Andrade et al. 2005) and Mato Grosso (Azevedo et al. 2002, Ribeiro et al. 2007 ).

The present study provides evidence for the presence of Ps. complexus in all evaluated ecotopes, including animal shelters in the periurban area. Although Ny. whitmani is thought of as the most important ACL vector in TO (Rangel & Lainson 2009, Vilela et al. 2011), the discovery of naturally L. (V.) braziliensis- infected Ps. complexus , the spatial distribution of this sandfly in forest and peridomiciliary ecotopes, its predominance in Shannon traps and its relatively high abundance in settlements and periurban areas, together with epidemiological evidence reported in the literature, suggest that Ps. complexus may also play a role in the transmission cycle of ACL in the rural settlement areas of Guaraí.

Ps. ayrozai , another sandfly species that is naturally infected by L. (V.) braziliensis in Guaraí, has been suggested as a putative vector of Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi in PA (Lainson et al. 1994, Lainson & Shaw 2005). Ps. ayrozai is an anthropophilic species (de Aguiar et al. 1985, Gomes & Galati 1989) and experimental infection studies have revealed its susceptibility to Leishmania (Leishmania) forattinii (Barretto et al. 1986, Lainson & Shaw 2005). Despite reports showing the vector competence of Ps. ayrozai , this species was not found frequently in this study and no further evidence was found of its participation in local transmission cycles.

Ny. antunesi, which was found in the rural settlement area, has been proven to be a Leishmania (Leishmania) lindenbergi vector in the northern PA and has been identified as anthropophilic in previous studies conducted in TO by Andrade Filho et al. (2001); however, cases of human infection by L. (V.) lindenbergi have not been reported in this study area thus far.

The ecoepidemiology of ACL in Brazil is strongly related to the transmission cycle of L. (V.) braziliensis and the vector Ny. whitmani , particularly in environmentally impacted areas, rural environments and the periphery of cities from all geographical regions. This new epidemiological profile has resulted from drastic environmental changes and the capacity of this sandfly to adapt to new ecological niches.

The Cerrado biome has experienced significant environmental impacts caused by deforestation. In this context, the establishment of highly populated, poor rural settlement groups and periurban areas without adequate infrastructure typically results in close contact between people and pathogen vectors.

This scenario has been frequently observed in TO and in this context, Ny. whitmani and Ps. complexus , as putative L. (V.) braziliensis vectors, likely maintain two transmission cycles in Guaraí: one related to the periurban area and the other in settlements in rural environments.

Acknowledge

To the staff of Laboratório de Transmissores de Leishmanioses, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz; Antonio Oliveira Santos; Francisco Marcos Alves de Oliveira, Maria Neusa Ferreira Nunes, Centro de Controle de Zoonoses/Secretaria Municipal de Saúde de Guaraí; Julio Gomes Bigeli, Núcleo das Leishmanioses, Secretaria da Saúde do Estado do Tocantins/Núcleo de Leishmanioses/Coordenadoria de Doenças Vetoriais e Zoonoses; Heloisa Maria Nogueira Diniz from Laboratório de Produção e Tratamento de Imagens, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz/FIOCRUZ for drawing the map. Mayumi D. Wakimoto for english review.

Appendix

The municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil.

Monitoring stations (MS) in rural settlement area, Agricultural Project Pedra Branca, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 1; C, D: MS 2.

Monitoring stations (MS) in periurban area, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 3; C, D: MS 4.

Products from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplex assays submitted to hybridisation analysis for the diagnosis of naturally Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in Psychodopygus complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai collected in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A: ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel revealing the 220 bp product form the cacophony gene amplification and the 120 bp fragment corresponding to the conserved region of kinetoplast minicircles from Leishmania spp [M: molecular weight marker (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 1: amplification reaction without added DNA (PCR negative control); 2-4: negative controls for the DNA extraction step (male insect pools): 5-8: female sandfly pools (5-7: Ps. complexus positive pools; 8: Ps. ayrozai positive pool); 9: PCR positive control (DNA extracted from a mixture of male insect pool containing L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes)]; B: dot hybridisation using a biotinylated probe specific for parasites from the Viannia subgenus.

![Products from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplex assays

submitted to hybridisation analysis for the diagnosis of naturally

Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in Psychodopygus

complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai collected in the municipality of

Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A: ethidium bromide-stained 2%

agarose gel revealing the 220 bp product form the cacophony gene

amplification and the 120 bp fragment corresponding to the conserved

region of kinetoplast minicircles from Leishmania spp [M: molecular

weight marker (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 1: amplification reaction

without added DNA (PCR negative control); 2-4: negative controls for

the DNA extraction step (male insect pools): 5-8: female sandfly

pools (5-7: Ps. complexus positive pools; 8: Ps. ayrozai positive

pool); 9: PCR positive control (DNA extracted from a mixture of male

insect pool containing L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes)]; B: dot

hybridisation using a biotinylated probe specific for parasites from

the Viannia subgenus.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/bfbb/3970607/135804a0941d/0074-0276-mioc-108-05-578-gs04.jpg)

Total number, percentage and Shannon-Wiener diversity (H) and evenness (J) indexes of phlebotomines captured in light traps in different ecotopes in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, January 2005-June 2007.

| Rural settlement area | Periurban area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring station 1 | Monitoring station 2 | Monitoring station 3 | Monitoring station 4 | |||||

| Species | Chicken coop n (%) | Forest n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Forest n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Pig sty n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Banana grove n (%) |

| Brumptomyia brumpti | - | 1 (0.28) | - | 3 (0.35) | 1 (0.77) | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) longipennis | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer | - | - | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.17) | 2 (2.56) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) villelai | - | 2 (0.56) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | 2 (2.56) |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | 4 (0.57) | 3 (0.84) | 6 (0.86) | 2 (0.24) | 3 (2.31) | 4 (1.29) | - | 5 (6.41) |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis a | 17 (2.40) | 9 (2.52) | 29 (4.17) | 2.12) | 20 (15.38) | 39 (12.54) | 80 (13.77) | 5 (6.41) |

| Lutzomyia (Tricholateralis) sherlocki | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei a | 60 (8.49) | 5 (1.40) | 2 (0.29) | 7 (0.83) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi | - | 2 (0.56) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pressatia choti | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Trichopygomyia dasydopogeton | 12 (1.70) | 21 (5.88) | 5 (0.72) | 14 (1.65) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) carmelinoi | 1 (0.14) | - | 3 (0.43) | 2 (0.24) | 5 (3.85) | 4 (1.29) | 6 (1.03) | 5 (6.41) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) lenti | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | 2 (0.24) | 2 (1.54) | 6 (1.93) | 4 (0.69) | 2 (2.56) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) evandroi | 3 (0.42) | - | - | 2 (0.24) | 1 (0.77) | 4 (1.29) | 3 (0.52) | 1 (1.28) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila | - | - | - | - | 5 (3.85) | 6 (1.93) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walkeri | 2 (0.28) | 1 (0.28) | 1 (0.14) | 8 (0.94) | - | - | - | - |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | 219 (30.98) | 68 (19.05) | 248 (35.68) | 213 (25.12) | 9 (6.92) | 3 (0.96) | 79 (13.60) | 14 (17.95) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) pinottii | - | 3 (0.84) | 7 (1.01) | 2 (0.24) | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) begonae | 41 (5.80) | 15 (4.20) | 10 (1.44) | 27 (3.18) | - | 2 (0.64) | 3 (0.52) | 4 (5.13) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) saulensis | 2 (0.28) | - | - | 5 (0.59) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides | - | - | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | 2 (1.54) | 7 (2.25) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) hermanlenti | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | 2 (1.54) | 14 (4.50) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) shannoni | - | 1 (0.28) | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Viannamyia furcata | - | - | 3 (0.43) | 2 (0.24) | - | - | - | - |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | 42 (5.94) | 49 (13.73) | 12 (1.73) | 92 (10.85) | 1 (0.77) | 2 (0.64) | 4 (0.69) | 4 (5.13) |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 80 (11.32) | 61 (17.09) | 42 (6.04) | 81 (9.55) | 12 (9.23) | 38 (12.22) | 36 (6.20) | 9 (11.54) |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 10 (1.41) | 19 (5.32) | 8 (1.15) | 26 (3.07) | - | 1 (0.32) | 5 (0.86) | 3 (3.85) |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | - | 5 (1.40) | - | 3 (0.35) | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 21 (2.97) | 14 (3.92) | 12 (1.73) | 37 (4.36) | 2 (1.54) | 8 (2.57) | 14 (2.41) | 5 (6.41) |

| Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus a | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 2 (0.28) | 10 (2.80) | 5 (0.72) | 7 (0.83) | - | 1 (0.32) | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | - | 2 (0.56) | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 115 (16.27) | 49 (13.73) | 292 (42.01) | 91 (10.73) | 7 (5.38) | 13 (4.18) | 10 (1.72) | 4 (5.13) |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | 65 (9.19) | 9 (2.52) | 6 (0.86) | 194 (22.88) | 58 (44.62) | 154 (49.52) | 329 (56.63) | 11 (14.10) |

| Nyssomyia intermedia a | - | - | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis a | 5 (0.71) | - | - | 3 (0.35) | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 707 (100) | 357 (100) | 695 (100) | 848 (100) | 130 (100) | 311 (100) | 581 (100) | 78 (100) |

| H | 0.9563 | 1.0850 | 0.6936 | 0.9755 | 0.7933 | 0.8149 | 0.6963 | 1.1238 |

| J | 0.6011 | 0.6819 | 0.4359 | 0.6131 | 0.4986 | 0.5517 | 0.4376 | 0.7063 |

a : vector species.

REFERENCES

- Andrade JD, Filho, Galati EAB, de Andrade WA, Falcão AL. Description of Micropygomyia (Silvamyia) echinatopharynx sp. nov. (Diptera: Psychodidae) a new species of Phlebotomine sand fly from the state of Tocantins, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:609–615. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade JD, Filho, Valente MB, de Andrade WA, Brazil RP, Falcão AL. Flebotomíneos do estado de Tocantins, Brasil (Diptera: Psychodidae) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2001;34:323–329. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822001000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade MS, Valença HF, Silva AL, Almeida FA, Almeida EL, Brito MEF, Brandão-Filho SP. Sandfly fauna in a military trainning area endemic for American tegumentary leishmaniasis in the Atlantic rain forest region of Pernambuco, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2005;21:1761–1767. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000600023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo ACR, Souza NA, Meneses CRV, Costa WA, Costa SM, Lima JB, Rangel EF. Ecology of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the north of the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:459–464. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud PJ. A simple method for carriage of living mosquitoes over long distances in the tropics. Indian J Med Res. 1929;17:281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto MP. Uma nova espécie de flebótomo do estado de Goiás, Brasil, e chave para determinação das espécies afins (Diptera: Psychodidae) Rev Bras Biol. 1946;6:427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Barretto AC, Vexenat JA, Peterson NE. The susceptibility of wild caught sand flies to infection by a subspecies of Leishmania mexicana isolated from Proechimys iheringi denigratus (Rodentia, Echimyidae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1986;81:235–236. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761986000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho BM. Estudos sobre os flebotomíneos (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) do município de Porto Nacional, estado de Tocantins, Monografia de Graduação em Ciências Biológicas. Universidade Estácio de Sá; Rio de Janeiro: 2008. 68 [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho GML, Brazil RP, Sanguinette CC, Andrade JD., Filho Description of a new phlebotomine species, Martinsmyia reginae sp. nov. (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) from a cave in the state of Tocantins, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105:336–340. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa SM da, Cechinel M, Bandeira V, Zannuncio JC, Lainson R, Rangel EF. Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani s.l. (Antunes & Coutinho, 1939) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae): geographical distribution and the epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil - Mini-review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:149–153. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar GM de, Vilela ML, Schuback PD, Soucasaux T, Azevedo ACR de. Aspectos da ecologia dos flebótomos do Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos, Rio de Janeiro. IV. Frequência mensal em armadilhas luminosas (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1985;80:465–482. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761984000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati EAB. Phylogenetic systematics of Phlebotominae (Diptera: Psychodidae) with emphasis on American groups. Bol Dir Malariol Saneam Amb. 1995;35:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Galati EAB. Rangel EF, Lainson R. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Fiocruz; Rio de Janeiro: 2003. Morfologia e taxonomia; pp. 23–206. [Google Scholar]

- Garcez LM, Soares DC, Chagas AP, Souza GCR, Miranda JFC, Fraiha H, Flöeter-Winter LM, Nunes HM, Zampiere RA, Shaw JJ. Etiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis and anthropophilic vectors in Jurití, Pará state, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:2291–2295. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AC, Galati EAB. Aspectos ecológicos da leishmaniose tegumentar americana. 7. Capacidade vetorial flebotomínea em ambiente florestal primário do Sistema da Serra do Mar, região do Vale do Ribeira, estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 1989;23:136–142. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101989000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graser C. Leishmaniose tegumentar americana no estado do Tocantins: situação epidemiológica e ocupacional, Monografia de Especialização em Saúde do Trabalhador e Ecologia Humana. Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca; Rio de Janeiro: 2008. 21 [Google Scholar]

- Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Cox FEG, Wakelin D, Gillespie SH, Despommier DD. Topley and Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections. 2nd ed. Hodder Arnold; London: 2005. New World leishmaniasis; pp. 313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lainson R, Shaw JJ, Silveira FT, de Souza AAA, Braga RR, Ishikawa EAY. The dermal leishmaniases of Brazil, with special reference to the eco-epidemiology of the disease in Amazonia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1994;89:435–443. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761994000300027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustosa ED, Naves HP, Carvalho MESD, Barbosa W. Contribuição ao conhecimento da fauna flebotomínica do estado de Goiás - 1984-1985. Rev Patol Trop. 1968;15:7–11. Nota Prévia I. [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes CB. A proposal of generic and subgeneric abbreviations for Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) of the world. Entomol News. 2007;118:351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Martins AV, Falcão AL, Silva JE. Nota sobre os flebotomíneos do estado de Goiás, com a descrição de duas espécies novas e da fêmea de Lutzomyia longipennis (Barreto, 1946) e a redescrição do macho de L. evandroi (Costa Lima & Antunes, 1936) (Diptera: Psychodidae) Rev Bras Malariol Doencas Trop. 1962;14:379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Martins AV, Falcão AL, Silva JE. Um novo flebótomo do estado de Goiás, Lutzomyia teratodes sp.n. (Diptera: Psychodidae) Rev Bras Biol. 1964;24:321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins AV, Falcão AL, Silva JE. Descrição de fêmea de Lutzomyia teratodes Martins, Falcão & Silva 1964 (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) Rev Bras Biol. 1975;35:515–517. [Google Scholar]

- MS/SVS - Ministério da Saúde/Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde . Manual de Vigilância da Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana. 2nd ed. MS/SVS; Brasília: 2007. 180 [Google Scholar]

- Pita-Pereira D, Alves CR, Souza MB, Brazil RP, Bertho AL, Barbosa AF, Britto CC. Identification of naturally infected Lutzomyia intermedia and Lutzomyia migonei with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) revealed by a PCR multiplex non-isotopic hybridization assay. Acta Trop. 2005;99:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugedo HR, Barata A, França-Silva AJ, Silva JC, Dias ES. HP: an improved model of suction light trap for the capture of small insects. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:70–72. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel EF. Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani and the eco-epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil; Workshop de Genética e Biologia Molecular de Insetos Vetores de Doenças Tropicais ; 13-17 September 2010; Recife. 2010. pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel EF, Lainson R. Proven and putative vectors of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil: aspects of their biology and vectorial competence. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:937–954. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000700001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro ALM, Missawa N, Zeilhofer P. Distribution of phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of medical importance in Mato Grosso state, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49:317–321. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DR, Hsi BP. An index of species abundance for use with mosquito surveillance data. Environ Entomol. 1979;8:1007–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues WC. DivEs - Diversidade de espécies. Versão 2.0. 2005. Available from: ebras.bio.br.

- SESAU/TO - Secretaria da Saúde do Estado do Tocantins, Núcleo de Leishmanioses, Coordenadoria de Doenças Vetoriais e Zoonoses Informe entomoepidemiológico das leishmanioses; 26ª a 29ª Semana Epidemiológica ; 24 July 2010; Palmas: SESAU; 2010. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Souza AAA, Ishikawa E, Braga R, Silveira F, Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Psychodopygus complexus, a new vector of Leishmania braziliensis to humans in Pará state, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:112–113. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudia WD, Chamberlain RW. Battery operated light trap, an improved model. Mosq News. 1962;22:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela ML, Azevedo ACR, Costa SM, Costa WA, Motta-Silva D, Grajauskas AM, Carvalho BM, Brahim LRN, Kozlowsky D, Rangel EF. Sand fly survey in the influence area of Peixe Angical hydroeletric plant, state of Tocantins, Brazil; 6th International Symposium on Phlebotomine Sandflies ; 27-31 October 2008; Lima: 2008. 55 [Google Scholar]

- Vilela ML, Graser-Azevedo C, Carvalho BM, Rangel EF. Phlebotomine Fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae) and putative vectors of leishmaniases in impacted area by hydroelectric plant, state of Tocantins, Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2011;6: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Rodrigues WC. DivEs - Diversidade de espécies. Versão 2.0. 2005. Available from: ebras.bio.br.

Supplementary Materials

The municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil.

Monitoring stations (MS) in rural settlement area, Agricultural Project Pedra Branca, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 1; C, D: MS 2.

Monitoring stations (MS) in periurban area, municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A, B: MS 3; C, D: MS 4.

Products from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplex assays submitted to hybridisation analysis for the diagnosis of naturally Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in Psychodopygus complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai collected in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A: ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel revealing the 220 bp product form the cacophony gene amplification and the 120 bp fragment corresponding to the conserved region of kinetoplast minicircles from Leishmania spp [M: molecular weight marker (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 1: amplification reaction without added DNA (PCR negative control); 2-4: negative controls for the DNA extraction step (male insect pools): 5-8: female sandfly pools (5-7: Ps. complexus positive pools; 8: Ps. ayrozai positive pool); 9: PCR positive control (DNA extracted from a mixture of male insect pool containing L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes)]; B: dot hybridisation using a biotinylated probe specific for parasites from the Viannia subgenus.

![Products from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplex assays

submitted to hybridisation analysis for the diagnosis of naturally

Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in Psychodopygus

complexus and Psychodopygus ayrozai collected in the municipality of

Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil. A: ethidium bromide-stained 2%

agarose gel revealing the 220 bp product form the cacophony gene

amplification and the 120 bp fragment corresponding to the conserved

region of kinetoplast minicircles from Leishmania spp [M: molecular

weight marker (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 1: amplification reaction

without added DNA (PCR negative control); 2-4: negative controls for

the DNA extraction step (male insect pools): 5-8: female sandfly

pools (5-7: Ps. complexus positive pools; 8: Ps. ayrozai positive

pool); 9: PCR positive control (DNA extracted from a mixture of male

insect pool containing L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes)]; B: dot

hybridisation using a biotinylated probe specific for parasites from

the Viannia subgenus.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/bfbb/3970607/135804a0941d/0074-0276-mioc-108-05-578-gs04.jpg)

Total number, percentage and Shannon-Wiener diversity (H) and evenness (J) indexes of phlebotomines captured in light traps in different ecotopes in the municipality of Guaraí, state of Tocantins, Brazil, January 2005-June 2007.

| Rural settlement area | Periurban area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring station 1 | Monitoring station 2 | Monitoring station 3 | Monitoring station 4 | |||||

| Species | Chicken coop n (%) | Forest n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Forest n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Pig sty n (%) | Chicken coop n (%) | Banana grove n (%) |

| Brumptomyia brumpti | - | 1 (0.28) | - | 3 (0.35) | 1 (0.77) | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) peresi | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) longipennis | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) quinquefer | - | - | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) rorotaensis | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.17) | 2 (2.56) |

| Micropygomyia (Sauromyia) villelai | - | 2 (0.56) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | 2 (2.56) |

| Sciopemyia sordellii | 4 (0.57) | 3 (0.84) | 6 (0.86) | 2 (0.24) | 3 (2.31) | 4 (1.29) | - | 5 (6.41) |

| Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis a | 17 (2.40) | 9 (2.52) | 29 (4.17) | 2.12) | 20 (15.38) | 39 (12.54) | 80 (13.77) | 5 (6.41) |

| Lutzomyia (Tricholateralis) sherlocki | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Migonemyia (Migonemyia) migonei a | 60 (8.49) | 5 (1.40) | 2 (0.29) | 7 (0.83) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) christenseni | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pintomyia (Pintomyia) damascenoi | - | 2 (0.56) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pressatia choti | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Trichopygomyia dasydopogeton | 12 (1.70) | 21 (5.88) | 5 (0.72) | 14 (1.65) | - | 1 (0.32) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) carmelinoi | 1 (0.14) | - | 3 (0.43) | 2 (0.24) | 5 (3.85) | 4 (1.29) | 6 (1.03) | 5 (6.41) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) lenti | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | 2 (0.24) | 2 (1.54) | 6 (1.93) | 4 (0.69) | 2 (2.56) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) evandroi | 3 (0.42) | - | - | 2 (0.24) | 1 (0.77) | 4 (1.29) | 3 (0.52) | 1 (1.28) |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) termitophila | - | - | - | - | 5 (3.85) | 6 (1.93) | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Evandromyia (Aldamyia) walkeri | 2 (0.28) | 1 (0.28) | 1 (0.14) | 8 (0.94) | - | - | - | - |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) bourrouli | 219 (30.98) | 68 (19.05) | 248 (35.68) | 213 (25.12) | 9 (6.92) | 3 (0.96) | 79 (13.60) | 14 (17.95) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) pinottii | - | 3 (0.84) | 7 (1.01) | 2 (0.24) | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) begonae | 41 (5.80) | 15 (4.20) | 10 (1.44) | 27 (3.18) | - | 2 (0.64) | 3 (0.52) | 4 (5.13) |

| Evandromyia (Evandromyia) saulensis | 2 (0.28) | - | - | 5 (0.59) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) runoides | - | - | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | 2 (1.54) | 7 (2.25) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) aragaoi | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Forattiniella) lutziana | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.32) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) hermanlenti | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | 2 (1.54) | 14 (4.50) | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Xiphomyia) dreisbachi | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) shannoni | - | 1 (0.28) | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Psathyromyia (Psathyromyia) dendrophyla | - | 1 (0.28) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Viannamyia furcata | - | - | 3 (0.43) | 2 (0.24) | - | - | - | - |

| Bichromomyia flaviscutellata a | 42 (5.94) | 49 (13.73) | 12 (1.73) | 92 (10.85) | 1 (0.77) | 2 (0.64) | 4 (0.69) | 4 (5.13) |

| Psychodopygus complexus a | 80 (11.32) | 61 (17.09) | 42 (6.04) | 81 (9.55) | 12 (9.23) | 38 (12.22) | 36 (6.20) | 9 (11.54) |

| Psychodopygus davisi | 10 (1.41) | 19 (5.32) | 8 (1.15) | 26 (3.07) | - | 1 (0.32) | 5 (0.86) | 3 (3.85) |

| Psychodopygus claustrei | - | 5 (1.40) | - | 3 (0.35) | - | - | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Psychodopygus llanosmartinsi | 21 (2.97) | 14 (3.92) | 12 (1.73) | 37 (4.36) | 2 (1.54) | 8 (2.57) | 14 (2.41) | 5 (6.41) |

| Psychodopygus hirsutus hirsutus a | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.28) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.12) | - | - | - | - |

| Psychodopygus ayrozai a | 2 (0.28) | 10 (2.80) | 5 (0.72) | 7 (0.83) | - | 1 (0.32) | - | 1 (1.28) |

| Psychodopygus paraensis a | - | 2 (0.56) | 1 (0.14) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nyssomyia antunesi a | 115 (16.27) | 49 (13.73) | 292 (42.01) | 91 (10.73) | 7 (5.38) | 13 (4.18) | 10 (1.72) | 4 (5.13) |

| Nyssomyia whitmani a | 65 (9.19) | 9 (2.52) | 6 (0.86) | 194 (22.88) | 58 (44.62) | 154 (49.52) | 329 (56.63) | 11 (14.10) |

| Nyssomyia intermedia a | - | - | - | 1 (0.12) | - | - | 1 (0.17) | - |

| Trichophoromyia ubiquitalis a | 5 (0.71) | - | - | 3 (0.35) | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 707 (100) | 357 (100) | 695 (100) | 848 (100) | 130 (100) | 311 (100) | 581 (100) | 78 (100) |

| H | 0.9563 | 1.0850 | 0.6936 | 0.9755 | 0.7933 | 0.8149 | 0.6963 | 1.1238 |

| J | 0.6011 | 0.6819 | 0.4359 | 0.6131 | 0.4986 | 0.5517 | 0.4376 | 0.7063 |

a : vector species.