Abstract

Phlebotomine sandflies of the genus Sergentomyia are widely distributed throughout the Old World. It has been suggested that Sergentomyia spp are involved in the transmission of Leishmania in India and Africa, whereas Phlebotomus spp are thought to be the sole vectors of Leishmania in the Old World. In this study, Leishmania major DNA was detected in one Sergentomyia minuta specimen that was collected in the southern region of Portugal. This study challenges the dogma that Leishmania is exclusively transmitted by species of the genus Phlebotomus in the Old World.

Keywords: Leishmania major, Sergentomyia minuta, vector

Leishmaniases are parasitic diseases caused by protozoans of the genus Leishmania. These parasites, which infect various wild and domestic mammals, are transmitted by the bite of phlebotomine sandflies. Species of the genus Sergentomyia are widely distributed throughout the Old World and are known to feed on reptiles as well as other vertebrates, including humans (Bates 2007, Berdjane-Brouk et al. 2012). Although these sandflies are considered vectors of lizard Sauroleishmania , it has been recently suggested that certain species of the genus Sergentomyia are involved in the transmission of Leishmania infantum among dogs in Senegal (Senghor et al. 2011) and Leishmania major DNA was detected in Sergentomyia darlingi in a cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) focus in Mali (Berdjane-Brouk et al. 2012). Earlier, Mukherjee et al. (1997) detected Leishmania donovani DNA in Sergentomyia spp in India.

In Portugal, 213 parasite strains have been isolated from sandflies and human and canine leishmaniasis cases have been identified as L. infantum, with Phlebotomus perniciosus and Phlebotomus ariasi as the proven vectors (Campino et al. 2006). However, L. major/L. infantum hybrids have also been isolated from four autochthonous human leishmaniasis cases, two of which were described elsewhere (Ravel et al. 2006). The identification of these multiple hybrids led to the hypothesis that L. major circulates in the country , most likely in infected sandflies. The risk of introduction of new Leishmania species in Portugal from travellers or immigrants from North Africa and the Indian subcontinent is a real concern, especially in the southern part of the country (Algarve region). Portuguese military missions in the Middle East pose an additional introduction risk.

An entomological surveillance study of phlebotomine species was performed during the last five years. During Leishmania transmission season, sandflies were captured by CDC miniature light traps and identified using entomological keys. Subsequently, kinetoplastid DNA-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers Uni21 and Lmj4 (Anders et al. 2002) and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-1 PCR analyses were used to screen female sandflies for Leishmania infection (Maia et al. 2009). After ITS1-PCR, Hae III digestion was performed on the positive PCR products to differentiate Leishmania species (Schonian et al. 2003).

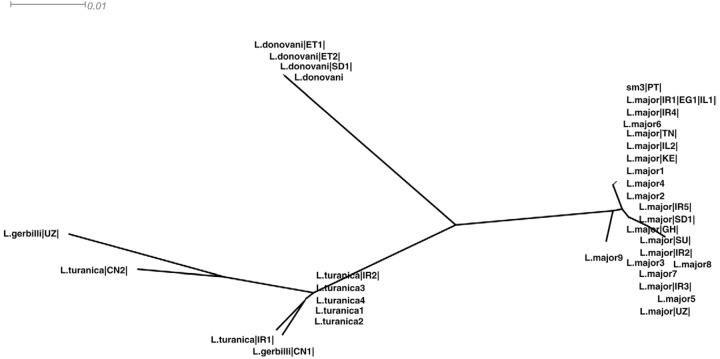

L. major DNA was detected in one Sergentomyia minuta specimen (sample sm3), which was collected in a rural area of the municipality of Albufeira, Algarve region. Furthermore, a characteristic L. major PCR product of 650 base pairs (bp) was obtained using the Uni21 and Lmj4 kinetoplastid primers as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis. After PCR amplification and Hae III digestion of the product, restriction fragments characteristic of L. major (203 bp and 132 bp) were observed. The amplified fragment obtained by ITS1-PCR was sequenced, aligned and compared with ITS-1 Leishmania sequences that were available in the GenBank database. A neighbour-joining tree (Figure) was constructed using SplitsTree4 (Huson & Bryant 2006) . The L. major sequence from sample sm3 had a high level of identity with L. major sequences from strains recovered in the Middle East and Northern Africa (Egypt, accession FJ460456.1, Iran, accessions FN677357.1, AY550178.1, AY260965.1, Israel, accessions EU326229.1, DQ300195.1 and Tunisia, accession FN677342.1).

Neighbour-joining unrooted tree built up from internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-1 sequence data of 195 characters from 37 sequences using Kimura-2P model with equal rates variation. Tree generated by SplitsTree4. Sequences used for these analysis (species code and accessions) were as follows: Leishmania major |IR1|,|IR2|,|IR3|,|IR4|,|IR5| (FN677357.1, AY550178.1, AY283793.1, AY260965.1, EF653269.1), L. major |EG1| (FJ460456.1), L. major |IL1|,|IL2| (EU326229.1, DQ300195.1), L. major |TN| (FN677342.1), L. major |UZ| (FN677357.1), L. major |SU| (AJ000310.1), L. major |KE| (AJ300482.1), L. major |GH| (DQ295825.1), L. major |SD| (AJ300481.1), L. major 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 (FJ753394.1, FJ753393.1, FJ753392.1, FJ753391.1, JF831924.1, FJ753395.1, EF413075.1, GQ402544.1, GQ402543.1), Leishmania turanica |IR1|,|IR2| (EU395712.1, JN860744.1), L. turanica |CN2| (HQ830350.1), L. turanica 1, 2, 3, 4 (AJ272380.1, AJ272379.1, AJ272378.1, HM130607.1), Leishmania gerbilli |CN1| (HQ830351.1), L. gerbilli |UZ| (AJ300486.1), Leishmania donovani |ET|,|ET2| (FN182209.1, FN182207.1), L. donovani |SD| (FN677362.1), L. donovani (AJ249620.1), sm3, Portuguese ITS-1 sequence. CN: China; EG: Egypt; ET: Ethiopia, GH: Ghana; IL: Israel; IR: Iran; KE: Kenya; PT: Portugal; SD: Sudan; SU: ex-URSS; TN: Tunisia; UZ: Uzbakistan.

The foci of CL caused by L. major occur in 14 countries of the World Health Organization--Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), extending from Morocco to Afghanistan (Postigo 2010). Although approximately 100,000 new CL cases were reported in the EMR in 2008, these were rarely caused by L. infantum. In contrast, L. infantum is the causative agent of CL in Western Europe. To date, no autochthonous human CL due to L. major has been identified in Portugal. However, unlike visceral leishmaniasis, the cutaneous clinical form is not under compulsory notification in the country and the misdiagnosis of cutaneous cases is frequent. Until now, the parasites were identified in only six CL cases: four strains were identified as zymodeme MON-1 (3) and MON-29 (1) (Campino et al. 2006) based on isoenzyme typing and two were identified by molecular typing. All of these cases were identified as L. infantum. It is imperative to know the causative agent, as the outcome and treatment may differ for L. infantum and L. major infections.

To our knowledge, this study presents the first detection of L. major DNA in a sandfly from the Sergentomyia genus in Europe. This finding challenges the dogma that Leishmania is exclusively transmitted by species of the genus Phlebotomus in the Old World and that Sergentomyia is exclusively a Sauroleishmania vector. Unfortunately, little prior work has been conducted regarding the development of Leishmania sp. in Sergentomyia sandflies . To determine the possible role of S. minuta in the transmission of L. major , it should be demonstrated that the species feeds on humans and that it supports the complete development of the parasite in natural conditions after the infectious blood meal has been digested.

L. major typically uses rodents as reservoir hosts and Jaouadi et al. (2013) have found Mus musculus DNA in S. minuta. These findings have prompted us to continue to examine Leishmania infection in rodents, namely in M. musculus , as it is common and widely distributed in the country. Few studies in rodents have been performed by our research group, although Leishmania infection has not been detected. However, Charrel et al. (2006) found Toscana virus, a virus responsible for human meningitis and encephalitis in Mediterranean countries, in S. minuta (Charrel et al. 2006); thus, the blood meal preferences of this species should also be studied to better understand if S. minuta can play a role in the transmission of human pathogens or vector borne diseases.

Further surveillance with extensive and systematic epidemiological surveys on Leishmania hosts and vectors are crucial given that increased migration, military deployments and other travel increase the risk of the introduction and spread of Leishmania species to non-endemic regions. Furthermore, the “new” parasites could be transmitted by sandfly species that are normally considered non-permissive to Leishmania infection. Eco-epidemiological and phylogenetic studies should be performed to clarify the introduction or evolution of L. major and potential reservoirs and vectors in Portugal. In addition, the national health services should be encouraged to improve CL diagnosis and parasite identification.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To I Mauricio, for critical and English revision, and to JM Cristóvão, for technical support.

Funding Statement

Financial support: EU/FEDER (PTDC/CVT/112371/2009) (FCT/MMCTES), EU (FP7-261504 EDENext) catalogued by the EDENext Steering Committee as EDENext093. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. CM (SFRH/BPD/44082/2008) and SC (SFRH/BPD/44450/2008) are FCT/MCTES fellows

REFERENCES

- Anders G, Eisenberger C, Jonas F, Greenblatt C. Distinguishing Leishmania tropica and Leishmania major in the Middle East using the polymerase chain reaction with kinetoplast DNA-specific primers. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(Suppl. 1):S87–S92. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates P. Transmission of Leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdjane-Brouk Z, Koné AK, Djimdé AA, Charrel RN, Ravel C, Delaunay P, del Giudice P, Diarra AZ, Doumbo S, Goita S, Thera MA, Depaquit J, Marty P, Doumbo OK, Izri A. First detection of Leishmania major DNA in Sergentomyia (Spelaeomyia) darlingi from cutaneous leishmaniasis foci in Mali. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campino L, Pratlong F, Abranches P, Rioux J, Santos-Gomes G, Alves-Pires C, Cortes S, Ramada J, Cristovão JM, Afonso MO, Dedet JP. Leishmaniasis in Portugal: enzyme polymorphism of Leishmania infantum based on the identification of 213 strains. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1708–1714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrel RN, Izri A, Temmam S, de Lamballerie X, Parola P. Toscana virus RNA in Sergentomyia minuta files. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1299–1300. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.060345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi K, Haouas N, Chaara D, Boudabous R, Gorcii M, Kidar A, Depaquit J, Pratlong F, Dedet JP, Babba H. Phlebotomine (Diptera, Psychodidae) blood meal sources in Tunisian cutaneous leishmaniasis foci: could Sergentomyia minuta, which is not an exclusive herpetophilic species, be implicated in the transmission of pathogens? Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2013;106:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Maia C, Afonso MO, Neto L, Dionísio L, Campino L. Molecular detection of Leishmania infantum in naturally infected Phlebotomus perniciosus from Algarve region, Portugal. J Vector Borne Dis. 2009;46:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Hassan MQ, Ghosh A, Ghosh KN, Bhattacharya A, Adhya S. Leishmania DNA in Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia species during a kala-azar epidemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:423–425. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo J. Leishmaniasis in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel C, Cortes S, Pratlong F, Morio F, Dedet J, Campino L. First report of genetic hybrids between two very divergent Leishmania species: Leishmania infantum and Leishmania major . Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1383–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonian G, Nazereddin A, Dinse N, Schweynoch C, Shallig H, Presber W, Jaffe C. PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senghor M, Niang A, Depaquit J, Faye M, Ferté H, Faye B, Gaye O, Elguero E, Alten B, Perktas U, Diarra K, Bañuls AL. Canine leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum transmitted by Sergentomyia species (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Senegal: ecological, parasitological and molecular evidences. 2011. Available from: isops7.org/ISOPS7_Abstract_book.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]