Abstract

Chagas disease, which is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is an important cause of heart failure. We investigated modifications in the cellular electrophysiological and calcium-handling characteristics of an infected mouse heart during the chronic phase of the disease. The patch-clamp technique was used to record action potentials (APs) and L-type Ca2+ and transient outward K+ currents. [Ca2+]i changes were determined using confocal microscopy. Infected ventricular cells showed prolonged APs, reduced transient outward K+ and L-type Ca2+ currents and reduced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Thus, the chronic phase of Chagas disease is characterised by cardiomyocyte dysfunction, which could lead to heart failure.

Keywords: Chagas disease, calcium current, action potential, potassium current, intracellular calcium, Trypanosoma cruzi

Chagas disease, which is caused by infection with the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is one of the leading causes of heart failure in Latin America (Marin-Neto et al. 2007). Currently, 10 million people are infected and 25 million people live in areas where the infectious parasites are present (WHO 2010). However, until now, few studies have provided compelling evidence of cardiomyocyte dysfunction during the establishment of heart failure following infection by T. cruzi (de Carvalho et al. 1992, Pacioretty et al. 1995, Roman-Campos et al. 2009b). Recently, new data have provided supporting evidence of how the left ventricular electrical-mechanical dysfunction observed during the initial stages of chagasic cardiomyopathy occurs (Esper et al. 2012, Roman-Campos et al. 2012). However, the cellular mechanisms underlying cardiomyocyte dysfunction during the late stages of Chagas disease remain unknown. Therefore, we sought to determine whether cardiomyocyte function is altered in the late phase of Chagas disease.

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally infected with 50 bloodstream trypomastigote forms of a Colombian T. cruzi strain (Federici et al. 1964). The experimental protocols were approved by the local animal use and care committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Adult left ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated using collagenase (1 mg/mL) with a calcium gradient method as previously described (Roman-Campos et al. 2009b). Myocytes were freshly isolated and stored in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium until they were used for experiments (within 4-6 h). Only calcium-tolerant, quiescent, rod-shaped myocytes showing clear cross-striations were used.

The whole-cell patch-clamp method was used in the current and voltage-clamp modes. All experiments were performed at room temperature (23-26ºC). To measure action potentials (APs) and transient outward K+ (Ito) and L-type Ca2+ currents (ICa,L), patch pipettes were filled with the appropriate internal solutions and bathed with external solutions as previously described (Roman-Campos et al. 2009a). APs were elicited at 1 Hz using short-current square pulses (3-5 ms). Ito was elicited by 3 s depolarisation pulses ranging from -40 to +70 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV at increments of 10 mV (15 s interval). ICa,L was measured at a holding potential of -80 mV, which was increased to -40 mV for 50 ms to inactivate Na+ and T-type Ca2+ channels. ICa,L was then measured at different membrane voltages between -40 and 50 mV (300 ms duration and 10 s intervals between test pulses).

Ca2+ imaging was performed in Fluo-4 AM (10 µM)-loaded cardiomyocytes that were stimulated at 1 Hz using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope equipped with an argon laser (488 nm) and a 63X oil immersion objective in line-scan mode (Roman-Campos et al. 2010). The intracellular Ca2+ levels were reported as the F/F0 ratio, where F is the maximal measured fluorescence and F0 is the background fluorescence. To fit Ca2+ transient decay, we used a mono-exponential function.

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For statistical analysis, we used Student's t test and n represents the number of different cells. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

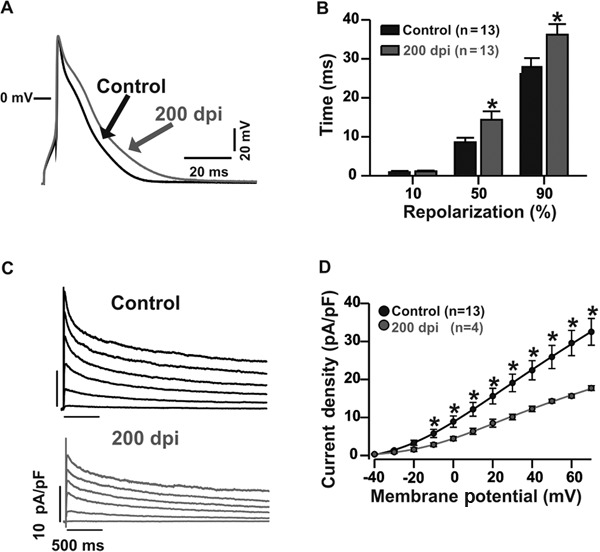

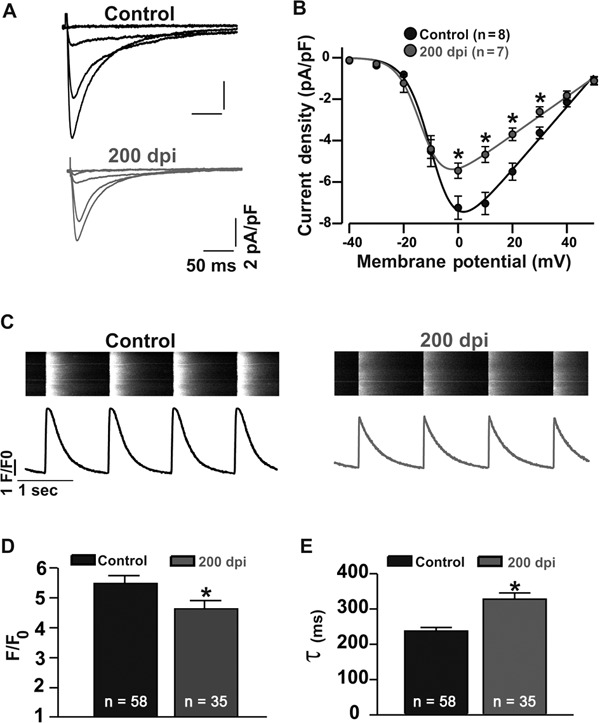

To study the cellular mechanism of cardiomyocyte dysfunction during the chronic phase of Chagas disease, in which T. cruzi is no longer observed in the bloodstream (Roman-Campos et al. 2009b), we first measured the transmembrane APs of cardiomyocytes isolated from control and infected mice [200 days post-infection (dpi) ]. Chagasic cardiomyopathy caused an increase in the time to AP repolarisation (APR). The lengths of time to 90% APR were 27.9 ± 2.2 ms (n = 13) and 36.2 ± 2.7 ms (n = 13) in control and infected mice, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). The regulation of APR in mouse cardiac myocytes is dependent on Ito (Roman-Campos et al. 2010). As shown in Fig. 1C, D, at 200 dpi, cardiomyocytes showed a significant reduction in Ito density. The peak outward K+ current density at +50 mV was 25.9 ± 3.0 pA/pF (n = 13) and 14.3 ± 0.5 pA/pF (n = 4) in control and infected cardiac myocytes, respectively. In addition to Ito, ICa,L also plays an important role in the control of AP waveform, mainly in the plateau phase. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, ICa,L was compromised in diseased mice. At 0 mV, the ICa,L was -7.2 ± 0.6 pA/pF (n = 8) and -5.5 ± 0.4 pA/pF (n = 7) in control and infected cardiac myocytes, respectively. Furthermore, ICa,L plays a central role in triggering calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR); thus, reduced ICa,L could impair calcium release from the SR (Roman-Campos et al. 2010). As shown in Fig. 2C, D, cardiomyocytes isolated from infected mice showed a ~17% reduction in calcium release from the SR compared to control cardiomyocytes. Additionally, calcium reuptake into the SR, which was measured as the calcium transient decay time constant, was slowed by ~39% in myocytes isolated from infected mice (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 1. prolonged action potential (AP) in chagasic cardiomyocyte at 200 days post-infection (dpi). A: representative AP traces from control (black) and chagasic cardiomyocytes (gray); B: AP repolarisation duration at different repolarisation levels; C: reduced transient outward K+ current (Ito) in Chagas disease; D: voltage-dependence of Ito plotted as current density (pA/pF) vs. membrane potential (mV) (control: black circles; chagasic cardiomyocytes: gray circles). Continuous lines were obtained by nonlinear regression analysis. Asterisks mean p ≤ 0.05. n: number of cells.

Fig. 2. disrupted excitation-contraction coupling in chagasic cardiomyocytes. A: representative ICa,L recordings from control (top) and chagasic cardiomyocytes (bottom); B: voltage-dependence of ICa,L plotted as current density (pA/pF) from -40 to 50 mV (control: black circles; chagasic cardiomyocytes: gray circles); C: representative intracellular global Ca2+ transients obtained from electrically stimulated myocytes (top). Ca2+ transient profile (bottom); D: significant reduction in peak Ca2+ transient amplitude observed in freshly isolated adult chagasic ventricular cardiomyocytes compared to the amplitude of control myocytes; E: time-constant of Ca2+ transient decay in chagasic and control cardiomyocytes. Asterisks mean p ≤ 0.05. dpi: days post-infection; n: number of cells.

In the present study, at 200 dpi, we showed that chagasic cardiomyopathy led to profound cardiomyocyte dysfunction due to (i) AP prolongation, (ii) reduced transient outward potassium and L-type calcium currents and (iii) reduced calcium release from the SR.

In previous studies, our and other groups have provided evidence showing that Chagas disease causes the disruption of heart and cardiomyocyte function, primarily due to a sustained inflammatory response, leading to nitric oxide and superoxide anion production (de Carvalho et al. 1992, Machado et al. 2000, Wen et al. 2006, Macao et al. 2007, Sales et al. 2008, Roman-Campos et al. 2009a, 2012). Additionally, it is accepted that sustained and excessive superoxide production is able to downregulate heart and cardiomyocyte function, mainly through the disruption of excitation-contraction coupling (Prosser et al. 2011) and reduction of Kv4.3 expression (Zhou et al. 2006). Nitric oxide is also able to differentially modulate cardiomyocyte function depending on its concentration (Gonzalez et al. 2008). Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that cardiomyocyte dysfunction during the late phase of Chagas disease is due to the excessive production of both nitric oxide (Roman-Campos et al. 2012) and superoxide anion.

Additionally, we observed reduced calcium release and slowed calcium reuptake into the SR at 200 dpi, both of which are hallmarks of human and mouse models of heart failure (Gwathmey et al. 1987, Lara et al. 2010, Roman-Campos et al. 2010). Thus, our results could explain the reduced heart function observed in the chronic phase of Chagas disease in mice (Jelicks et al. 2002) and may be translated to humans (Marin-Neto et al. 2007). However, additional studies with human cardiac tissue are necessary to confirm this possibility.

REFERENCES

- Carvalho AC de, Tanowitz HB, Wittner M, Dermietzel R, Roy C, Hertzberg EL, Spray DC. Gap junction distribution is altered between cardiac myocytes infected with Trypanosoma cruzi . Circ Res. 1992;70:733–742. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper L, Roman-Campos D, Lara A, Brant F, Castro LL, Barroso A, Araujo RR, Vieira LQ, Mukherjee S, Gomes ER, Rocha NN, Ramos IP, Lisanti MP, Campos CF, Arantes RM, Guatimosim S, Weiss LM, Cruz JS, Tanowitz HB, Teixeira MM, Machado FS. Role of SOCS2 in modulating heart damage and function in a murine model of acute Chagas disease. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici EE, Abelmann WH, Neva FA. Chronic and progressive myocarditis and myositis in C3h mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi . Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1964;13:272–280. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1964.13.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez DR, Fernandez IC, Ordenes PP, Treuer AV, Eller G, Boric MP. Differential role of S-nitrosylation and the NO-cGMP-PKG pathway in cardiac contractility. Nitric Oxide. 2008;18:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2007.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Copelas L, MacKinnon R, Schoen FJ, Feldman MD, Grossman W, Morgan JP. Abnormal intracellular calcium handling in myocardium from patients with end-stage heart failure. Circ Res. 1987;61:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelicks LA, Chandra M, Shtutin V, Petkova SB, Tang B, Christ GJ, Factor SM, Wittner M, Huang H, Douglas SA, Weiss LM, Orleans-Juste PD, Shirani J, Tanowitz HB. Clin Sci. Suppl. 48. Vol. 103. Lond: 2002. Phosphoramidon treatment improves the consequences of chagasic heart disease in mice; pp. 267S–271S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara A, Damasceno DD, Pires R, Gros R, Gomes ER, Gavioli M, Lima RF, Guimaraes D, Lima P, Bueno CR, Jr, Vasconcelos A, Roman-Campos D, Menezes CA, Sirvente RA, Salemi VM, Mady C, Caron MG, Ferreira AJ, Brum PC, Resende RR, Cruz JS, Gomez MV, Prado VF, Almeida AP de, Prado MA, Guatimosim S. Dysautonomia due to reduced cholinergic neurotransmission causes cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1746–1756. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00996-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macao LB, Wilhelm D, Filho, Pedrosa RC, Pereira A, Backes P, Torres MA, Frode TS. Antioxidant therapy attenuates oxidative stress in chronic cardiopathy associated with Chagas' disease. Int J Cardiol. 2007;123:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado FS, Martins GA, Aliberti JC, Mestriner FL, Cunha FQ, Silva JS. Trypanosoma cruzi - infected cardiomyocytes produce chemokines and cytokines that trigger potent nitric oxide-dependent trypanocidal activity. Circulation. 2000;102:3003–3008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Neto JA, Cunha-Neto E, Maciel BC, Simoes MV. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1109–1123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacioretty LM, Barr SC, Han WP, Gilmour RF., Jr Reduction of the transient outward potassium current in a canine model of Chagas disease. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:1258–1264. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: rapid mechano-chemo transduction in heart. Science. 2011;333:1440–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1202768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Campos D, Campos AC, Gioda CR, Campos PP, Medeiros MA, Cruz JS. Cardiac structural changes and electrical remodeling in a thiamine-deficiency model in rats. Life Sci. 2009a;84:817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Campos D, Duarte HL, Gomes ER, Castro CH, Guatimosim S, Natali AJ, Almeida AP, Pesquero JB, Pesquero JL, Cruz JS. Investigation of the cardiomyocyte dysfunction in bradykinin type 2 receptor knockout mice. Life Sci. 2010;87:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Campos D, Duarte HL, Sales PA, Jr, Natali AJ, Ropert C, Gazzinelli RT, Cruz JS. Changes in cellular contractility and cytokines profile during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009b;104:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Campos D, Sales-Junior PA, Duarte HL, Gomes ER, Lara A, Rocha NN, Resende RR, Ferreira A, Guatimosim S, Gazzinelli RT, Ropert C, Cruz JS. Novel insights into the development of chagasic cardiomyopathy: role of PI3Kinase/NO axis. Int J Cardiol. 2012;S0167-5273:01126–01136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales PA, Jr, Golgher D, Oliveira RV, Vieira V, Arantes RM, Lannes-Vieira J, Gazzinelli RT. The regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells have a limited role on pathogenesis of infection with Trypanosoma cruzi . Microbes Infect. 2008;10:680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen JJ, Yachelini PC, Sembaj A, Manzur RE, Garg NJ. Increased oxidative stress is correlated with mitochondrial dysfunction in chagasic patients. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) fact sheet (revised in June 2010) Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2010;85:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Ziegler C, Birder LA, Stewart AF, Levitan ES. Angiotensin II and stretch activate NADPH oxidase to destabilize cardiac Kv4.3 channel mRNA. Circ Res. 2006;98:1040–1047. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218989.52072.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]