Abstract

Background and Purpose

In the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial, addition of clopidogrel to aspirin was associated with an unexpected increase in mortality in patients with lacunar strokes. We assessed the effect of the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on mortality in a meta-analysis of published randomized trials.

Methods

Randomized trials in which clopidogrel was added to aspirin in subjects with vascular disease or vascular risk factors were identified. Trials were restricted to those with a mean follow-up of ≥14 days in which both the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel was tested and mortality was reported.

Results

Twelve trials included 90 934 participants (mean age, 63 years; 70% men; median follow-up, 1 year) with 6849 observed deaths. There was no significant increase in mortality with the combination therapy either in 4 short-term (14 days–3 months; OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87– 0.99) or in 7 long-term (>3 months; hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.91–1.04) trials after 1 long-term trial (the SPS3 trial) was excluded because of heterogeneity. Addition of clopidogrel was associated with an increase in fatal hemorrhage (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.97–1.90) and a reduction in myocardial infarction (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74–0.91).

Conclusions

The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin has no overall effect on mortality. The SPS3 trial results are outliers, possibly because of a lower prevalence of coronary artery ischemia. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin increases fatal bleeding and reduces myocardial infarction.

Keywords: clopidogrel, antiplatelet therapy, clinical trials, mortality, lacunar stroke

Dual antiplatelet therapy of clopidogrel combined with aspirin is standard antithrombotic therapy after coronary and carotid arteries stent placement and for patients with acute coronary syndromes. In the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial involving patients with recent lacunar strokes, the addition of clopidogrel 75 mg daily to aspirin 325 mg daily was associated with an unexpected increase in all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.5; P=0.005).1

We sought to determine the effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on mortality in patients with a wide spectrum of vascular disease; we conducted systematic identification of all randomized trials comparing these agents and meta-analysis of their results. To understand further the effects on mortality, we examined the effects of addition of clopidogrel on vascular versus nonvascular death, fatal bleeding, and myocardial infarction. Adverse mortality effects of combining clopidogrel with aspirin are relevant to ongoing randomized trials testing this combination.2,3

Methods

Search and Selection Process

Randomized trials in which clopidogrel in any dosage was added to aspirin in any dosage and in which all-cause mortality was reported were included. Trials were excluded if follow-up averaged <14 days or if published only in abstract. Trials were identified by computerized search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov Web site, and Pubmed using the keywords of clopidogrel plus aspirin combined with clinical trial; inquiry to the manufacturer of Plavix brand of clopidogrel was also made.

Data Extraction

Two physician reviewers (S.P., R.G.H.) independently extracted the following from published sources: data on methodological features; number of patients treated; total follow-up exposure; and occurrence of all-cause mortality, causes of death, death caused by hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, and intracranial hemorrhage. Disagreements were resolved by joint review and consensus. If the years of exposure for each treatment arm were not provided, they were estimated from the number of primary events divided by the annualized event rate; if the overall mortality rate was not provided, then the mean follow-up multiplied by the number of participants was used. The biostatistician reviewer (L.A.P.) extracted available data on hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% CIs for the long-term trials.

Outcomes

We accepted the definitions of vascular versus nonvascular causes of death as reported in the individual clinical trials. For these analyses, deaths categorized as of unknown cause were combined with vascular deaths (ie, vascular deaths included all deaths that were not determined to be nonvascular). We accepted the diagnosis of myocardial infarction as reported in individual trials.

Data Synthesis

Intention-to-treat results were used for the analyses when available (and footnoted when not available). Meta-analyses of the trial results are presented as ORs comparing dual antiplatelet versus aspirin, with the exception of all-cause mortality results for longer-term trials, in which the HR was estimated instead. (Meta-analysis of other long-term trial results as an HR was not performed, as data were less available.) Each meta-analysis OR was computed assuming a random effects model, and the assumption of statistical homogeneity of the treatment effect (across trials) was tested using the QL statistic for the relative odds scale. If the count in 1 or more of the cells for a trial was 0, then 0.5 was added to each of the 4 cells. The meta-analysis HR for all-cause mortality in longer-term trials was computed using a generic inverse variance method for continuous data. The log (HR) and standard error for each trial result were calculated from the published HR and 95% CI. For 1 trial (CURE), HR data for overall mortality were not reported, so OR data were used; and for a relatively small trial (CASCADE), total deaths numbered 1, so data were excluded.4 Heterogeneity across trials was evaluated using the I2 index (percentage of the total variability in a set of effect sizes because of between-studies variability) and the χ2 test for heterogeneity. All tests and CIs are 2-sided. Software used for meta-analysis of ORs and HRs were MedCalc for Windows, version 12.1.4.0 (MedCalc Software) and RevMan 5.0 (the Cochrane Collaboration), respectively.5

Results

Twelve randomized trials published between 2001 and 2012 were included, with a total of 90 934 randomized participants with a mean age of 63 years, a mean follow-up of 1 year per patient, and 6849 total deaths.1,6–16 (Table 1) Numbers of participants ranged from 113 to 45 852 and average follow-up from 15 days to 2.3 years. Trial cohorts mainly included patients with vascular diseases (acute coronary syndromes, coronary artery bypass grafting, peripheral vascular revascularization, atrial fibrillation, recent lacunar stroke), but 1 trial (CHARISMA) also included patients with vascular risk factors without clinically manifest vascular disease10 (Table 1). In the 8 trials in which follow-up averaged >3 months, clopidogrel versus placebo were administered double-blind.

Table 1.

Design Features and Baseline Characteristics Participants

| N | Mean Age, y |

Men % | DM % | Previous Stroke/TIA % |

Main Inclusion | Primary Outcome | ASA Dose, mg/d |

CPD Dose, mg/d |

Average Follow-Up |

% Lost to Follow-Up |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term Trials (14 d–3 mo) | |||||||||||

| CPD and ASA after surgery in CAD6 2007–2009 | 249 | 59 | 83 | 40 | 5 | Elective CABG | Graft occlusion at 3 mo | 100 | 75 | 3 mo | 3.6 |

| ASA vs ASA and CPD in lower limb angioplasty7 2002–2003 | 132 | 66 | 77 | 12 | NR | Leg atherosclerosis undergoing revascularization | Platelet responsiveness to stimulation | 75 | 300 ×1 then 75 | 30 d | none |

| PROCLAIM8 2005–2006 | 181 | 56 | 43 | NR | NR | Metabolic syndrome | Inflammatory markers | 81 | 75 | 6 wk | none |

| COMMIT9 1999–2005 | 45 852 | 61 | 72 | NR | NR | Acute MI with ST changes | Death/reinfarction/stroke and death from any cause | 162 | 75 | 15 d | <1 |

| Long-Term Trials (>3 mo) | |||||||||||

| SPS31 2003–2012 | 3020 | 63 | 63 | 37 | NR | Recent lacunar stroke | Recurrent stroke | 325 | 75 | 3.5 y | NR |

| CHARISMA10 2002–2004 | 15 603 | 64 | 70 | 42 | 25 | CV disease or multiple risk factors | Stroke, MI, and vascular death | 75–162 | 75 | 2.3 y | <1 |

| CURE11 1998–2000 | 12 562 | 64 | 62 | 23 | 4 | Acute coronary syndrome | Stroke, MI, and vascular death | 75–325 | 300 ×1 then 75 | 9 mo | <1 |

| ACTIVE A12 2003–2008 | 7554 | 71 | 58 | 19 | 13 | AF+1 risk factor | Stroke, MI, and vascular death | 96%: 75–100 3.5 %>100 | 75 | 3.6 y | <1 |

| CASCADE13 2006–2009 | 113 | 67 | 89 | 29 | NR | CABG with saphenous vein | Graft hyperplasia at 1 y | 162 | 75 | 1 y | none |

| CREDO14 1999–2001 | 2116 | 62 | 71 | 26 | 7 | Elective PCI | All death, stroke, MI | 325×28 d; then 81–325 | 300 ×1 then 75 | 1 y | 4 |

| REAL-LATE/ZEST-LATE15 2007–2010 | 2701 | 62 | 70 | 26 | 4 | Drug-eluting stents for 12 mo | MI or death from cardiac causes | 100–200 | 75 | 1.6 y | <1 |

| CASPAR16 2004–2006 | 851 | 66 | 76 | 38 | NR | Bypass for PVD | Graft occlusion or revascularization, amputation or death | 75–100 | 75 | 1 y | 2 |

| All trials | 90 934 | 63 | 70 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 75 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

DM indicates diabetes mellitus; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ASA, aspirin; CPD, clopidogrel; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; NR, not reported; MI, myocardial infarction; CV, cardiovascular; AF, atrial fibrillation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Mortality

Four trials with short duration of follow-up (14 days–3 months) included 46 414 participants with 3572 deaths, and were dominated by the large COMMIT trial.9 (Table 2) Meta-analysis of these trials showed all-cause mortality was reduced by dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin alone (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87– 0.99; I2 index, 0%; P=0.94 for heterogeneity).

Table 2.

All-Cause Mortality in Randomized Trials Testing Clopidogrel Added to Aspirin

| #Deaths/#Randomized |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term Trials (14 d–3 mo) | Population | Combination | Aspirin Alone | OR (95% CI) |

| Clopidogrel and aspirin after surgery in CAD6 | CABG surgery | 0/124 | 1/125 | 0.33* (0.01–8.26) |

| Aspirin vs aspirin and clopidogrel in lower limb angioplasty7 | Leg atherosclerosis undergoing revascularization | 0/67 | 0/65 | 0.97* (0.02–50) |

| PROCLAIM8 | Metabolic syndrome | 0/89 | 0/92 | 1.03* (0.02–53) |

| COMMIT9 | Acute MI with ST changes | 1726/22 961 | 1845/22 891 | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) |

| All short-term trials | 1726/23 241 | 1846/23 173 | 0.93 (0.87–0.99)† | |

| #Deaths/#Randomized (Annualized Mortality Rate) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|||

| Long-Term Trials (> 3 mo) | Population | Combination | Aspirin Alone | |

| SPS31 | Recent lacunar stroke | 113/1517 (2.1%/pt-yr) | 77/1503 (1.4%/pt-yr) | 1.49 (1.11–2.01) |

| CHARISMA10 | Vascular disease or risk factors | 371/7802 (2.0%/pt-yr) | 374/7801 (2.1%/pt-yr) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

| CURE11 | Acute coronary syndromes | 359/6259 (7.6%/pt-yr) | 390/6303 (8.3%/pt-yr) | 0.92 (0.80–1.07)‡ |

| ACTIVE A12 | Atrial fibrillation unsuitable for warfarin | 825/3772 (6.4%/pt-yr) | 841/3782 (6.6%/pt-yr) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) |

| CASCADE13 | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 0/56 (0%/pt-yr) | 1/57 (1.8%/pt-yr) | ⋯ |

| CREDO14 | Percutaneous coronary intervention | 18/1053 (≈1.7%/pt-yr) | 24/1063 (≈2.3%/pt-yr) | 0.75 (0.41–1.39) |

| REAL-LATE / ZEST-LATE15 | Drug-eluting stents >12 mo | 20/1357 (0.9%/pt-yr) | 13/1344 (0.6%/pt-yr) | 1.52 (0.75–3.50) |

| CASPAR16 | Lower extremity bypass | 24/425 (5.6%/pt-yr) | 17/426 (4.0%/pt-yr) | 1.44 (0.70–2.68) |

| All longer-term trials | 1730/22 241 | 1737/22 279 | 1.03 (0.91–1.16)§ | |

| Longer-term trials except SPS3 | ⋯ | 1617/20 724 | 1660/20 776 | 0.97 (0.91–1.04)¶ |

CAD indicates coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MI, myocardial infarction.

Estimated by adding 0.5 to each cell.

I2 index, 0%; P=0.94 for heterogeneity.

OR reported for mortality.

I2 index, 48%; P=0.07 for heterogeneity.

I2 index, 0%; P=0.56 for heterogeneity.

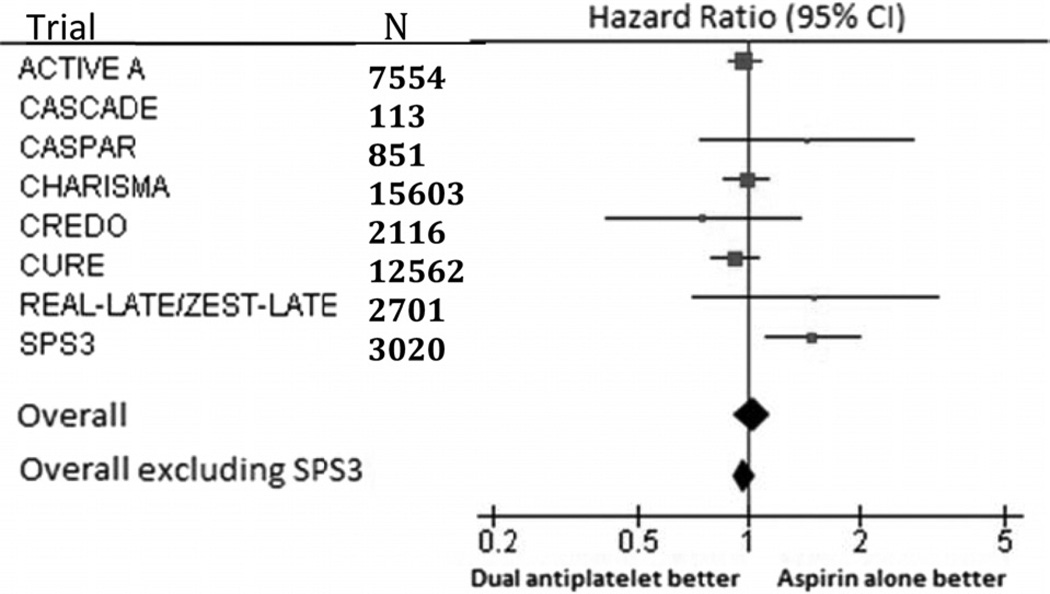

Eight trials with longer duration of average follow-up (>3 months) included 44 520 participants with 3467 deaths (Table 2). Meta-analysis of these trials showed no effect on mortality of dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin alone (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.91–1.16; Table 2); however, there was moderate heterogeneity among the results (I2 index, 48%; P=0.07 for heterogeneity). After excluding the SPS3 trial, meta-analysis of the remaining 7 trials showed no effect of dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin alone on mortality (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.91–1.04) with no indication of heterogeneity of results across trials (I2 index, 0%; P=0.56 for heterogeneity; Figure 1).

Figure.

Meta-analysis of long-term (>3 months) trials.

Cause of death was reported as vascular versus nonvascular in 6 longer-term follow-up trials. (Table 3) The OR by meta-analysis for vascular death by dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin alone was 1.05 (95% CI 0.91–1.20); however, there was moderate heterogeneity among the trial results (I2 index, 43%, P=0.12 for heterogeneity). Excluding the SPS3 trial (OR, 1.61, 95% CI, 1.11–2.36), the OR estimate was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.91–1.08; I2 index, 0%; P=0.61 for heterogeneity). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across the trials for nonvascular death, and the OR estimate by meta-analysis was 0.95 (95% CI 0.83–1.09; I2 index, 0%; P=0.83 for heterogeneity).

Table 3.

Etiologies of Death: Vascular Versus Nonvascular in Longer-Term Follow-Up Trials

| Trial | Etiology | Combination # of Deaths |

Aspirin Alone # of Deaths |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS31 | Vascular | 72* | 45* | 1.61 (1.11–2.36) |

| Nonvascular | 41 | 32 | 1.28 (0.80–2.04) | |

| CHARISMA10 | Vascular | 238 | 229 | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) |

| Nonvascular | 133 | 145 | 0.92 (0.72–1.16) | |

| CURE11 | Vascular | 318 | 345 | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) |

| Nonvascular | 41 | 45 | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) | |

| ACTIVE A12 | Vascular | 600 | 599 | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) |

| Nonvascular | 225 | 242 | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) | |

| CASCADE13 | Vascular | 0 | 1 | 0.33† (0.01–8.36) |

| Nonvascular | 0 | 0 | 1.02† (0.02–52) | |

| CREDO14 | Vascular | NR | NR | |

| Nonvascular | NR | NR | ||

| REAL-LATE/ZEST-LATE15 | Vascular | 13‡ | 8‡ | 1.62 (0.67–3.91) |

| Nonvascular | 7 | 5 | 1.39 (0.44–4.39) | |

| CASPAR16 | Vascular | NR | NR | |

| Nonvascular | NR | NR | ||

| All longer-term trials | Vascular | 1241 | 1227 | 1.05 (0.91–1.20) |

| Excluding SPS3 | 1169 | 1182 | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | |

| Nonvascular | 447 | 469 | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) |

NR indicates not reported.

Vascular includes probable vascular and unknown causes.

Estimated by adding 0.5 to each cell.

Cardiac causes assumed to be vascular.

Fatal Bleeding

Six longer-term follow-up trials reported the number of fatal hemorrhages (Table 4). Results for SPS3 were not available. The OR by meta-analysis for fatal hemorrhage among patients assigned to dual antiplatelet therapy was 1.35 (95% CI, 0.97–1.90; I2 index, 0%; P=0.57 for heterogeneity).

Table 4.

Effect of Clopidogrel Added to Aspirin on Fatal Hemorrhage in Longer-Term Follow-Up Trials

| Trial | Combination # of Events |

Aspirin Alone # of Events |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPS31 | NR | NR | ⋯ |

| CHARISMA10 | 26 | 17 | 1.53 (0.83–2.82) |

| CURE11 | 11 | 15 | 0.74 (0.34–1.61) |

| ACTIVE A12 | 42 | 27 | 1.57 (0.96–2.55) |

| CASCADE13 | 0 | 0 | 1.02* (0.02–52) |

| CREDO14 | NR | NR | ⋯ |

| REAL LATE-ZEST LATE15 | NR | NR | ⋯ |

| CASPAR16 | 2 | 1 | 2.01 (0.18–22) |

| All longer-term trials | 81 | 60 | 1.35 (0.97–1.90) |

NR indicates not reported.

Estimated by adding 0.5 to each cell.

Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarctions were significantly reduced (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74–0.91; I2 index, 2%; P=0.41 for heterogeneity) when clopidogrel was added to aspirin based on meta-analysis of 7 longer-term follow-up trials (Table 5). The effect was of similar magnitude, but no longer significant when 3 trials involving patients with acute coronary syndromes (CURE) or undergoing coronary stent placement (CREDO, REAL–LATE/ZEST-LATE) were excluded (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.73–1.04; I2 index, 9%; P=0.35 for heterogeneity). Fatal myocardial infarctions were not reported in any trial.

Table 5.

Effect of Clopidogrel Added to Aspirin on Myocardial Infarction in Longer-Term Follow-Up Trials

| Trial | Combination # of MIs |

Aspirin Alone # of MIs |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPS31 | 30 | 38 | 0.78 (0.48 –1.26) |

| CHARISMA*10 | 185 | 197 | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) |

| CURE11 | 324 | 419 | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) |

| ACTIVE A12 | 90 | 115 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) |

| CASCADE13 | 4 | 1 | 4.31 (0.47–40) |

| CREDO14 | 70 | 90 | 0.77 (0.56–1.07) |

| REAL LATE-ZEST LATE15 | 10 | 7 | 1.42 (0.54–3.74) |

| CASPAR†16 | NR | NR | |

| All longer-term Trials | 713 | 867 | 0.82 (0.74–0.91) |

MI indicates myocardial infarction; NR, not reported.

Only nonfatal MIs reported in the main results article; all MIs estimated from Table 3 in the Berger PB, et al. (6).

Hazard ratio reported: combination vs aspirin alone: HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.32–2.06; P=0.66.

Excluded Trials

Trials that were excluded from these analyses and the reasons for exclusion are given in Appendix I (online data). For example, in 1 trial involving participants with acute myocardial infarction, 30-day mortality data are available, but randomly assigned clopidogrel versus aspirin was given only for the initial 2 to 4 days before coronary intervention was undertaken.17 A small trial involving 392 patients with acute transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke followed for 90 days did not report total mortality.18

Discussion

Based on analysis of all published randomized trials, addition of clopidogrel to aspirin does not affect overall mortality. In trials with long-term follow-up, a trend toward an increase in fatal hemorrhage with dual antiplatelet therapy (35%; 95% CI, −3% to 90%) was offset by a significant reduction in myocardial infarction (18%; 95% CI, 9%–26%). There was no impact on vascular death as reported in a subset of the trials. The 50% increase (P=0.005) in mortality associated with addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in the SPS3 trial involving patients with recent lacunar stroke was an outlier when considered in the context of the other randomized trials.

Several subgroup analyses dealing with mortality from the large CHARISMA (2002–2006) trial have been published and may shed light on the aberrant mortality results reported from the SPS3 trial. The CHARISMA trial included 15 603 patients with vascular disease or multiple vascular risk factors randomized to aspirin (dose range, 75–162 mg daily) alone versus combined with clopidogrel 75 mg daily, administered double-blind. There was no difference in all-cause mortality (371 deaths with dual antiplatelet therapy versus 374 deaths with aspirin alone, 2.0%/pt-yr versus 2.1%/pt-yr; HR, 0.99) during the mean follow-up of 2.3 years. The investigators published 3 subsequent secondary analyses addressing the issue of clopidogrel added to aspirin and mortality. Wang et al19 reported mortality rates according to whether participants enrolled with asymptomatic (n=3284) versus symptomatic vascular disease (n=12 153) and found an unanticipated interaction (P for interaction=0.02) between symptom status and effect of addition of clopidogrel on all-cause mortality: all-cause mortality was increased in asymptomatic patients by dual antiplatelet therapy (HR, 1.4; P=0.04) versus decreased in those with symptoms (HR, 0.91 P=0.27).19 Asymptomatic participants were much more often diabetic (83%) than were symptomatic patients (31%); fatal bleeding did not account for the excess in deaths among asymptomatic patients. A second post hoc analysis considered diabetes and diabetic nephropathy (microalbuminuria ≥30 µg/mL as reported by local investigators) and concluded that patients having diabetic nephropathy was related to increased mortality in patients assigned to clopidogrel.20 A third analysis examined bleeding complications and found a strong independent relationship between moderate bleeding and all-cause mortality (HR, 2.9; P<0.0001).21

The aspirin dosage (325 mg daily, enteric-coated) used in SPS3 is higher than that used in most other randomized trials testing dual antiplatelet therapy. Higher aspirin doses have been associated with increased rates of life-threatening bleeding when combined with clopidogrel.22,23 However, in a large trial involving 12 566 patients with acute coronary syndromes, participants randomly assigned to aspirin 300 to 325 mg daily versus 75 to 100 mg daily combined with clopidogrel 75 mg daily had no increase in mortality (143 deaths with high-dose aspirin, 156 deaths with low-dose aspirin; HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.74–1.16).24

Limitations of this meta-analysis include that it is based on published data and not on pooling of individual patient data, and therefore it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses according to history of coronary heart disease or to explore consistency of the treatment effects on mortality in key subgroups.

We hypothesize that in cohorts with a sufficiently high frequency of coronary artery disease, addition of clopidogrel to aspirin results in a neutral effect on mortality, explained by a reduction in myocardial infarction being offset by increases in fatal hemorrhage and moderate hemorrhage that are associated with death. Cohorts with overall low mortality rates and low frequencies of coronary artery disease, such as the SPS3 cohort and asymptomatic subgroup of the CHARISMA trial, may have increased mortality with dual antiplatelet therapy because the absolute reduction in coronary events does not offset death related directly or indirectly to bleeding complications.

However, we cannot exclude that the results of SPS3 could be caused by extreme play of chance. Nevertheless, we hypothesize that the chronic use of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin may adversely affect mortality compared with aspirin monotherapy in cohorts with low rates of coronary artery ischemia, such as those participating in the SPS3 trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

All authors were involved in the SPS3 trial sponsored by the NINDS (NCT00059306).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Benavente O on behalf of the SPS3 Investigators. The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) Trial: Results of the Antiplatelet Intervention. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association International Stroke Conference; February 03, 2012; New Orleans USA. www.strokeconfence.org Session XIII: Plenary Session. Friday, February 3, 2012;11:30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston C. Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) Trial. NCT00991029. [Access date March 12, 2012]; www.clinicaltrials.gov. Last Updated on January 23, 2012.

- 3.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, et al. Rationale and design of the dual antiplatelet therapy study, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of 12 versus 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with either drug-eluting stent or bare metal stent placement for the treatment of coronary artery lesions. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 2004;23:1817. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reviewer Manager (RevMan) (Computer Program) Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao G, Zheng Z, Pi Y, Lu B, Lu J, Hu S. Aspirin plus clopidogrel therapy increases early venous graft patency after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1639–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassar K, Ford I, Greaves M, Bachoo P, Brittenden J. Randomized clinical trial of the antiplatelet effects of aspirin-clopidogrel combination versus aspirin alone after lower limb angioplasty. British J of Surg. 2005;92:159–165. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willerson T, Cable G, Yeh E on behalf of the PROCLAIM investigators. PROCLAIM: pilot study to examine the effects of clopidogrel on inflammatory markers in patients with metabolic syndrome receiving low-dose aspirin. Texas Heart Inst J. 2009;36:530–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, Xie J, Pan H, Peto R, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomized placebo-controlled trial (COMMIT) Lancet. 2005;366:1607–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67660-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke E, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognomi G, Fox KK. Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Hart RG, Hohnloser S, Pfeffer M, Chrolavicius S, et al. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulik A, Le May MR, Voisine P, Tardif J-C, DeLarochelliere R, Naidoo S, et al. Aspirin plus clopidogrel versus aspirin alone after coronary artery bypass grafting: the clopidogrel after surgery for coronary artery disease (CASCADE) Trial. Circ. 2010;122:2680–2687. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, III, Frey ETA, Delago A, Wilmer C, et al. for the CREDO Investigators. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2411–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SJ, Park DW, Kim YH, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, et al. Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1374–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belch JJF, Dormandy J the CASPAR Writing Committee. Results of the randomized, placebo-controlled clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid in bypass surgery for peripheral arterial disease (CASPAR) trial. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1179–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM FASTER Investigators. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961–969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang TH, Bhatt DL Fox KAA on behalf of the CHARISMA Investigators. An analysis of mortality rates with dual-antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention population of the CHARISMA trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2200–2207. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasgupta A, Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL for the CHARISMA Investigators. Clinical outcomes of patients with diabetic nephropathy randomized to clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone (a post hoc analysis of the clopidogrel for high atherothrombotic risk and ischemic stabilization, management, and avoidance [CHARISMA] trial) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Fuster V for the CHARISMA Investigators. Bleeding complications with dual antiplatelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease: results from the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance [CHARISMA] trial. Circ. 2010;121:2575–2583. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.895342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:379–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators. Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, Diaz R, Elkelboom JW, Fox KA. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:930–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters RJG, Mehta SR, Fox KAA, Zhao F, Lewis BS, Kopecky S, et al. for the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Trial Investigators. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study. Circulation. 2003;108:1682–1687. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091201.39590.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.