Major depression, a common mental illness affecting millions of people worldwide, is one of the leading causes of morbidity and has a significant economic cost. Although the mechanisms of action are not well understood, antidepressants, including serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), have been used for the treatment of depression, anxiety and other psychiatric disorders.1 Here we identified a Wnt signaling inhibitor,2 secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3), as a molecular target of antidepressant treatments in rodent models, and revealed the significant association of three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in FRZB (the sFRP3 human ortholog) with early antidepressant responses in a clinical cohort.

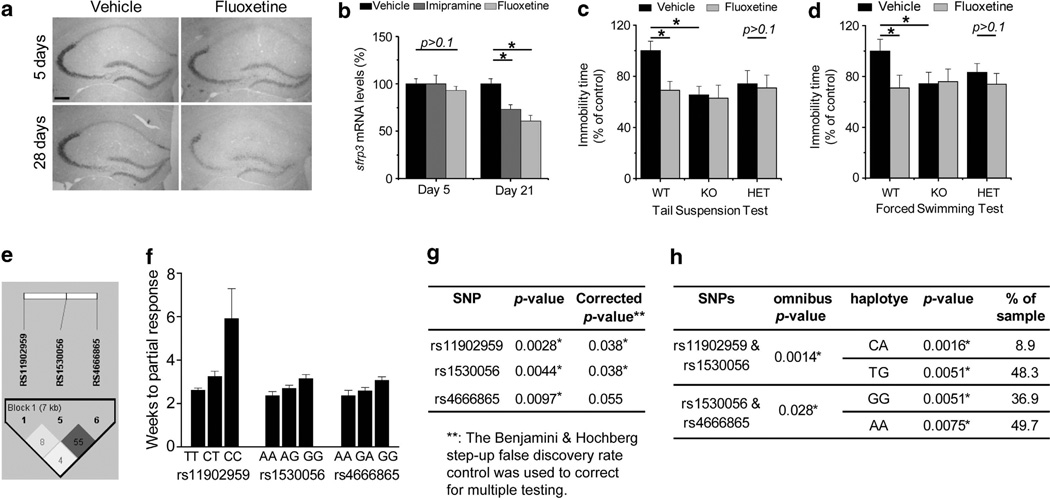

In our previous screening of differential gene expression upon electroconvulsive stimulation, a treatment for patients with drug-resistant major depression, levels of sFRP3 were significantly reduced in the adult mouse hippocampus.3 In situ analysis further showed that sFRP3 is highly expressed in the dentate gyrus and CA3 regions4 (Figure 1a). Interestingly, chronic but not subchronic treatments with fluoxetine (SSRIs; 20 mg/kg/day) or imipramine (TCAs; 20 mg/kg/day) also significantly suppressed sFRP3 expression in the hippocampus (Figures 1a and b). Thus, sFRP3 is a common downstream target of multiple, mechanistically distinct treatments for depression.

Figure 1.

(a, b) Downregulation of secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3) expression by chronic treatment with antidepressants in adult mouse hippocampus. Shown in (a) are sample in situ images of tissues processed in parallel from mice that received 28-day fluoxetine treatment (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.). Scale bar: 200 µm. Shown in (b) is a summary of quantitative real-time PCR analysis of sFRP3 expression levels in the hippocampus of adult wild-type (WT) mice after subchronic (5 days) or chronic (21 days) treatments of imipramine (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.) or fluoxetine (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.), respectively. Values are normalized to that of vehicle-treated animals at each time point and represent mean ± s.e.m. (n=5 to 10 animals for each time point; *P<0.01, Student’s t-test; P>0.1, analysis of variance with a Dunnett’s post-hoc test) (c, d.) Depression-like behavioral tests in the adult sFRP3 KO and WT male mice after chronic treatment with fluoxetine (20 mg/kg body weight, i.p.; once daily for 4 weeks). Shown in (c) is a summary of the tail-suspension test. Total time spent immobile was recorded during the last 4 min of the 6-min testing period. Shown in (d) is a summary of the forced-swimming test. Total time spent immobile was recorded during the last 4 min of the 6-min testing period. Values are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (n=15–23 animals; *P<0.01, Student’s t-test). e–h. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms on FRZB with latency to partial response to antidepressants. Shown in (e) is the linkage disequilibrium structure in r-squared among three associated SNPs within 541 patients. Shown in (f) is the summary plot of latency to partial response to antidepressant for genotypes of three associated SNPs (rs11902959, rs1530056 and rs4666865) in FRZB. Value are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (For rs11902959, CC: N=3, CT: N=94, TT: N=444; for rs1530056, AA: N=152, AG: N=252; GG: N=137; for rs4666865, AA; N=213, GA: N=239, GG: N=89.) Shown in (g) is a summary table of association analysis of three associated SNPs with latency to partial response using an allelic model in PLINK version 1.07. The Benjamini & Hochberg step-up false discovery rate control was used to correct for multiple testing. Shown in (h) is a summary table of association analysis of haplotypes of three associated SNPs with latency to partial response using a haplotype QTL module in PLINK version 1.07.

The function of sFRP3 in the nervous system is unknown. To test the possibility that sFRP3 downregulation mediates antidepressant action, we subjected sFRP3 knockout (KO) mice to a panel of behavioral analyses (see Supplementary Information). sFRP3 KO mice exhibited apparently normal development and no differences in locomotor activity and anxiety-like behaviors in the open-field, elevated-plus maze and light–dark tests compared to wild-type (WT) littermates (Supplementary Figures 1a–g). In tail-suspension and forced-swimming tests, which are reliable predictors of antidepressant potential,5 vehicle-treated adult KO or heterozygous (HET) mice showed significantly reduced levels of immobility compared to WT animals (Figures 1c and d and Supplementary Figures 1h and i). Notably, fluoxetine treatment did not cause a further decrease in immobility in KO and HET mice (Figures 1c and d), indicating that sFRP3 downregulation alone is sufficient to induce antidepression-like behavioral responses.

Responses of patients with major depression to antidepressant treatment can be influenced by genetic variations.6 In parallel to animal studies, we conducted a pharmacogenetic association study of the human sFRP3 gene (FRZB) in a cohort of 541 Caucasian patients with major depression,7 with latency to antidepressant response and partial response (50% or 25% decrease in symptom severity, respectively). We assessed 19 SNPs spanning 10 kb from 3′ to 5′ of the FRZB locus (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3a). All SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. While no SNPs showed significant association with latency to response, two SNPs located 3′ of the gene (rs11902959/P=0.0028; rs1530056/P=0.0044) and one SNP in the 3′-untranslated region (rs4666865/P=0.0097) exhibited significant association with latency to partial response, with rs11902959 and rs1530056 surviving multiple testing corrections (P=0.038) and rs4666865 showing a trend–level association (P=0.055; Figures 1e–g and Supplementary Figure 2b). All SNPs showed a gene–dose dependent effect (Figure 1f). χ2 test revealed no difference in allele frequencies of these three SNPs between patients with unipolar depression and healthy subjects8 (Supplementary Figure 3b), excluding a potential contribution from a skewed allelic frequency in better or worse responding groups. These SNPs are in moderate to low linkage disequilibrium (Figure 1e) and appear to represent at least two distinct loci of association. To investigate the potential joint effects of these variants, we performed haplotype-based association tests. The rs11902959/rs1530056 haplotype gave an omnibus P-value of 0.0014, with a highly significant association of the CA haplotype (P=0.0016; frequency=8.9%) and TG haplotype (P=0.0051; frequency=48.3%). The rs1530056/rs4666865 haplotype also showed a significant overall association (P=0.028) and associations of the GG haplotype (P=0.0051; frequency=36.9%) and AA haplotype (P=0.0075; frequency=49.7%; Figure 1h). To gain insight into the function of these SNP variants, we investigated a public database for SNP genotype statistical associations with transcript expression in human brains.9 Interestingly, rs1530056 (P=0.04) and rs44666865 (P=0.02) showed significant association with FRZB expression and the major allele A predicted lower FRZB expression levels in both SNPs in a gene–dose dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 4). This result corroborates pharmacogenetic association results in which the A allele in both SNPs was associated with a better response to antidepressant treatment. These convergent results from pharmacogenetic and SNP expression association analyses suggest that functionally relevant polymorphisms in FRZB contribute to antidepressant response in clinical cohorts, potentially via differential regulation of FRZB expression.

Despite being effective, antidepressant pharmacotherapy is hampered by the slow onset of clinically appreciable improvement and significant side effects. Recent studies have suggested Wnt signaling as a target for mood disorder treatment.10 Our studies identify a novel function of sFRP3, a naturally secreted inhibitor of Wnt signaling, as an essential mediator of antidepressant actions in animal models, and reveal significant association of its polymorphisms with latency to antidepressant response in patients with depression. Targeting of sFRP3 may represent a novel therapeutic approach for depression treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr Binder receives grant support from NIMH, Behrens-Weise Foundation and the Seventh Framework Program from the European Commission. Dr Binder is also a coinventor on the following patents: FKBP5: a novel target for antidepressant therapy (International publication number: WO 2005/054500) and Polymorphisms in ABCB1 associated with a lack of clinical response to medicaments (International application number: PCT/EP2005/005194).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All other auhors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

REFERENCES

- 1.Belmaker RH, Agam G. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones SE, Jomary C. Bioessays. 2002;24:811–820. doi: 10.1002/bies.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo JU, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1345–1351. doi: 10.1038/nn.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lein ES, Zhao X, Gage FH. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3879–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4710-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cryan JF, Mombereau C, Vassout A. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:571–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horstmann S, Binder EB. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:57–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennings JM, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohli MA, et al. Neuron. 2011;70:252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colantuoni C, et al. Nature. 2011;478:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duman RS, Voleti B. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.