Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the perspectives of twelve low income, second generation Latinas seeking to enter therapy for depression. Qualitative data collected at the time of a diagnostic interview (SCID) using Motivational Interviewing techniques, included an assessment of women’s motivation to enter therapy and confidence that she could follow through with treatment. Data were analyzed using Constructivist Grounded Theory and revealed six positive and six painful motivators that catalyzed the women towards treatment amidst complications related to “self” and “time”. Despite demanding schedules for taking care of their families, finances, current or estranged partners, and work responsibilities women were determined to get help for their depression.

Keywords: depression, Latinas, motivation, therapy, access

Major depressive disorder is the most prevalent lifetime DSM-IV disorder (Kessler et al., 2005). Among Mexican Americans, the prevalence of major depressive disorder among females is almost twice that of males (Vega, Sribney, Aguilar-Gaxiola, & Kolody, 2004) with the prevalence of the disorder among US-born Mexican Americans higher than those born in Mexico (Grant et al. 2004; Huang, Wong, Ronzia, & Yu, 2007; Vega et al., 2004). The vast majority of people in the U.S. with depression and other psychiatric disorders, including Latinos, do not obtain professional treatment (Lagomasino et al., 2005; Nadeem, Lange, & Miranda, 2008; Ojeda & McGuire, 2006; Wang, Lane, et al., 2005) or delay treatment-seeking for many years (Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005) despite advances in both effective interventions and service delivery (Collins, Westra, Dozois, & Burns, 2004; Wells et al., 2002).

Many barriers to accessing care delays help-seeking for depression and Latinos are aware of these obstacles (Martinez Pincay, & Guarnaccia, 2007). Major contributors to unmet needs or inadequate mental healthcare for Latinos include having a low income, a lack of insurance, or a limited education (Alegría et al., 2002; Dwight-Johnson, Sherbourne, Liao, & Wells, 2000; Ojeda & McGuire, 2006; Wang, Berglund et al., 2005). Self awareness of changes in one’s own mental health is another important component of seeking treatment for emotional problems. However, compared with whites, Latinos are less likely to recognize symptoms of poor mental health and to seek treatment (Givens, Houston, Van Voorhees, Ford, & Cooper, 2007; Zuvekas & Fleishman, 2008). Latinos are also less likely to accept a diagnosis of depression from their healthcare provider (Givens et al., 2007). Nonetheless, when they do seek care, Latinos are more likely to prefer counseling over antidepressants (Cooper et al., 2003; Givens et al., 2007; Nadeem et al., 2008) particularly for women and those who have a greater understanding of counseling (Dwight-Johnson et al., 2000). Still, very little insight is available about what specifically motivates Latinas to take action and enter treatment for depression.

The current study was focused on qualitative data collected during the first phase of a two phase pilot study with low income, second generation Latinas who were struggling with features of depression and were seeking therapeutic help. The primary aim was to explore and describe the women’s perspective before entering therapy on what motivated and what impeded their efforts to enter therapy. A secondary aim was to explore and describe the women’s sense of confidence in their ability to act on their desire to get treatment. This included their confidence that they could commit to and follow through with depression treatment.

Method

Design

Project Well Being (PWB) was a two phase pilot study that targeted depressed, low income, second generation Latinas of Central American and Mexican descent living in a large metropolitan area of California. The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the ethical protection of research subjects. The unique cultural situation of second generation Latinas was critical to the design of every aspect of this study. Latina mental health experts (who were and were not Latinos/as themselves) and Latina community members were consulted throughout the planning and implementation of the study so that cultural sensitivity was honored. The Spanish- and English-speaking nurse-therapist (second author) had been involved in clinical work and research specifically with first and second generation Latinas with low incomes for over 20 years at the time of this study. Her commitment to cultural sensitivity was another key aspect of the work.

Phase I of PWB involved a diagnostic interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) (Version 2.0) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) and further assessment using Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Thus, throughout the SCID, the interviewer was directive but not controlling and used MI to ask about confidence and motivation at the end of the assessment. All interested second generation Latinas between the ages of 18 and 50 years who scored 10 or greater on the Beck Depression Inventory-II were invited to participate in the interview of Phase I of PWB. The interview was from 1.5 to 2.5 hours in length. The current analysis focuses solely on the qualitative data collected in Phase I. However, Phase II of the study (reported elsewhere) involved an 8-week depression treatment program of nurse-led, short term Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) (Beck, 1995) integrated with Motivational Interviewing techniques (Arkowitz & Burke, 2008; Miller, & Rollnick, 2002). Demographic information was collected during the Phase I interview.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

In Phase I, several modules of the SCID (First et al., 1997) were administered including that for mood disorders plus mood differential (including major depressive episode past and present, mania, hypomania, bipolar, and dysthymia), psychosis and differential diagnosis of psychotic disorders, and the alcohol and substance abuse modules. For the standard administration of the SCID, the interviewer asks descriptive yet specific questions and seeks definitive answers. Long answers or tangents are not encouraged. To protect the integrity of the SCID, techniques for doing an accurate diagnostic interview overrode methodological techniques for qualitative interviewing. However, with this difficult-to-engage population, the nurse-therapist allowed the women to speak as they were comfortable in the spirit of Miller and Rollnick’s MI (2002) and the nurse-therapist drew on MI-techniques for interviewing when appropriate. Thus many of the women gave much longer responses to the SCID-questions in the form of stories and chronologies of events in their lives. The women had the freedom to elaborate using detailed answers. Because Latinas who participated in Phase I may not have accessed mental health services ever before in their lives, the IRB required that the nurse-researcher not be solely focused on depression, but be ready to follow up on any and all other problems raised in the course of the SCID. Thus, protocols were in place for following up on other problems such as suicide ideation and psychosis.

Motivation Assessment

MI was originally developed as a pre-treatment intervention for overcoming the ambivalence that keeps people from making desired changes in their lives (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The use of MI is considered to be an important pre-treatment step to facilitate engagement in therapy for depression (Zuckoff, Swartz, & Grote, 2008). During Phase I of this study but after the SCID was completed, the nurse-therapist continued the interview by doing a motivational assessment drawing on the techniques of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Each woman was asked how important it was that she enter therapy now, and why, as well as what could possibly make it more important to her. Then, each woman was asked how confident she was that she could enter and follow through with a therapeutic program like PWB. Also, the reasons for her level of confidence were explored which gave further insight into what motivated her (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Finally, she was asked about what keeps her from feeling more confident that she could engage in therapy to deal with the depression, which shed light on perceived barriers. During the Phase I interview, various MI techniques were used as needed such as expressing desire to learn from the participant, reflecting back (Arkowitz & Burke, 2008), asking strategic open-ended questions, rolling with resistance, eliciting change talk, building discrepancy, and enhancing confidence (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) to explore questions about motivation, readiness, and confidence.

Recruitment and Sample

Community-based recruitment was done from January to July of 2007 and involved seven healthcare, child development, and family service sites that serve low income clients in a large metropolitan area in Southern California. No recruitment occurred at any mental health facilities. Flyers were distributed with a headline that read: “Feeling sad? Hopeless? Depressed? Wonder if you’ll ever fell “good” again?”, and continued with a description of the study (see Figure 1). Several but not all women had seen the flyer before inquiring about the study and all women were given a copy of the flyer to keep at the time of screening. Latinas aged 18–50 years who were born or grew up in the U.S. starting before age 18 but whose parents were born in Mexico or Central America, who were eligible for services at one of the participating non-profit agencies that serves only low income clients, who spoke English, and who scored 10 or higher on BDI-II were eligible for Phase I of PWB. Eligibility criteria excluded women who were pregnant or in the postpartum period and those dealing with bereavement.

Figure 1.

Flyer for Project Well Being (Painting by Chadwick, 2002).

A total of 29 women called to inquire about the study and of those, 12 women met inclusion criteria for the Phase I interview and gave informed consent to participate. Others were ineligible due to ethnicity other than Latina, age greater than 50 years, or because they were already in psychiatric care elsewhere. The interview was audio-taped with the participant’s permission and transcribed verbatim. Women received $35.00 in cash upon completion of the Phase I interview.

Data Analysis

Constructivist Grounded Theory techniques (Charmaz, 2006) were used to analyze the qualitative data that women gave in response to the SCID and the MI-based questions. During data analysis, initial coding was done to break down, examine, and compare data with data. Focused coding was then used to identify categories that were further analyzed to uncover subcategories, dimensions, and properties. Memos were written to preserve ideas throughout the data analysis regarding emerging conceptual categories (Charmaz, 2006). Analysis was done with specific care to focus on each participant’s original views in her own words. That is, words or phrases that first had been used by the nurse-therapist in dialogue during the Phase I interview but then happened to be repeated by the participant, were not included in the analysis.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 12 women who participated in Phase I of PWB, five were referred by a health or social service professional, four were referred by friends who were already in the study, and three women were motivated to inquire about the study solely as a result of seeing a flyer. Of the 12, four had immigrated to the US as children and eight were US-born. All were bilingual in Spanish and English but the interviews were done almost entirely in English. Ages ranged from 20 to 48 years; the average age was 29 years. Partner status was complex. Eleven of the 12 women were currently not partnered. Eight women had been in committed partnerships or had lived with partners in the past, three were involved with significant others in the past but did not have formal commitments or had not lived with them, and one was currently living with her boyfriend. Of the four, two had had past relationships with women. Of the 12, five women had been legally married. Eight women had children, ranging from one to 25 years of age. One woman also periodically cared for five additional children who were nieces, nephews, and children of her estranged ex-partner. As noted, currently one woman was living with her boyfriend, six were living with their parents or extended family, four were living on their own, and one was living with friends (an older couple who were concerned about her welfare). Only women who were eligible for services at participating agencies that serve low-income families could participate in PWB. One woman was an undergraduate at a university, four had attended a junior college, six had completed high school or the equivalent, and one woman completed ninth grade. In terms of employment, three women worked full time and one was on disability, but had been employed full time; all four of these women had health insurance. Six women worked part time. Of them, the university student had health insurance but the rest of the part time workers did not. Two women were unemployed and did not have health insurance.

SCID and Motivational Assessment

During the SCID and the motivational assessment, the nurse-therapist provided ample opportunity for the women to voice resistance to entering therapy. However, all 12 participants rated therapy as highly important and also rated their confidence to engage in therapy to be at the highest level. Women spoke freely about that which motivated them to get help. In all, the women described six positive motivators and six painful motivators.

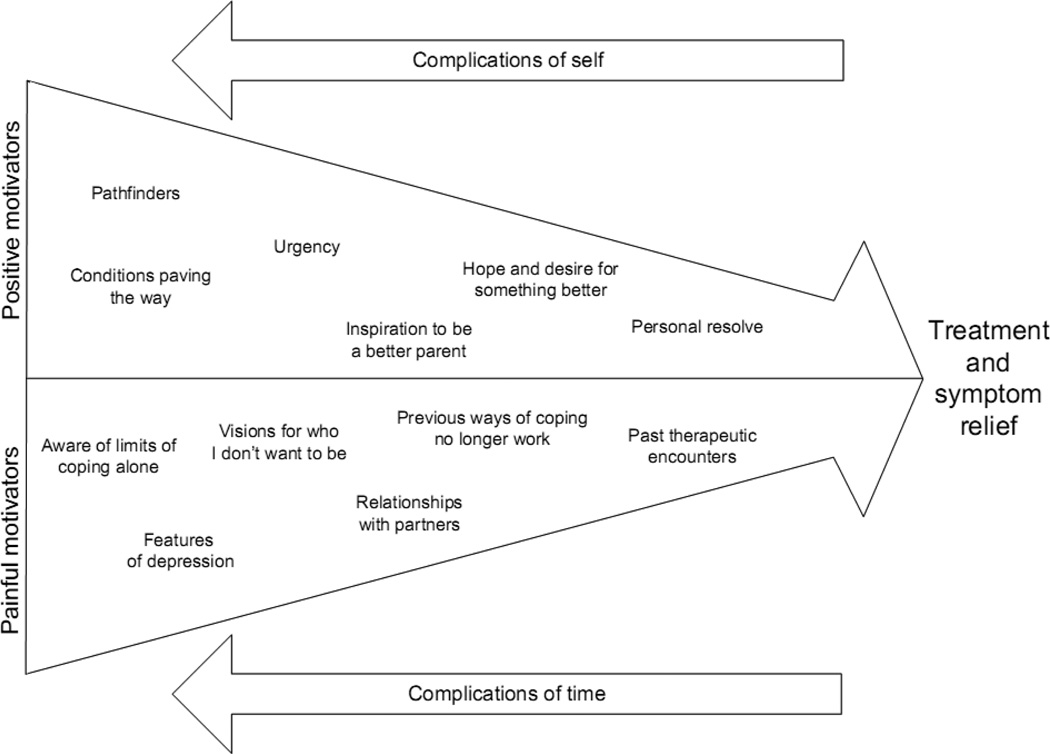

When asked about barriers, the women did not respond with descriptions of actual impediments. Instead their stories reflected the overriding complications of “self” and “time” as complexities that affected how they experienced both positive and painful motivators. The experience of both these positive and painful motivators provided the momentum to get treatment for symptom relief (see Figure 2). However, the complications of self and time also brought ambivalence that worked against forward momentum. That is, self and time brought hesitations that stalled or caused a backward drag in their dynamic movement towards accessing help.

Figure 2.

Momentum to Enter Therapy for Depression for Second Generation Latinas of Low Income (N=12)

Matters of self as a complication

While the ability to help others was valued highly by the women, they sensed that self-acceptance was a necessary precursor to success in life, particularly to healthy giving. This was exemplified by a woman who said, “Because it’s essential, in order for you to do anything else in life, in order to fulfill anybody else’s needs, you have to be at ease with yourself, you have to feel good with yourself.” Matters of the self complicated their efforts to enter therapy for depression because historically, and for various reasons, the women avoided or omitted self-examination and self-reflection. In their rush to put others’ needs before their own, the women put off becoming aware of the magnitude of their distress. One woman said: “I don’t know if I’ve ever tried to pay attention to my, myself”. Various others said that they never sought therapy for their own needs in the past despite many hard times because they were only concentrating on their friends’, parents’, and relatives’ needs. For example, one woman explained that even if she received healthcare services for various physical illnesses from a medical doctor, she did not receive treatment or advice for her emotional health from her physician because the focus was not on her. The woman explained that where emotional problems were concerned, all of her focus and efforts were funneled towards solving her son’s emotional problems rather than her own. She said, “We’re working on my son, not me”. She described her failure to tend to her own needs as “part of my problem. I put off things that I need to do for me because they don’t seem important.” However, she explained that she now needed to prioritize her own needs saying, “I need a break from doing for everybody else. I know this [entering therapy] probably will be the first step that I would take to do something for me. And if I get it done, then I know I’m gonna get everything else for me done too.” In this, she acknowledged that the act of entering PWB would be the first time she actually did anything involving therapeutic services for herself.

Time as a complication

Laced throughout the women’s narratives was an understanding of time as a complicating factor that pervaded all aspects of their lives. They had many responsibilities and a sense of inadequate time to attend to all that was before them. The women explained that they needed more than the eight sessions that the study offered, but they simultaneously wrestled with the reality that their busy lives did not leave them a moment to spare. One said, “I am very overwhelmed. I’m just like on a time limit now and it feels like the time is not gonna be enough to get done what I need to. I can’t even shower if I wanted to.” Another woman spoke about being too busy to pay attention to herself in the way that is required in therapy, saying, “I don’t know if I’ve ever tried to pay attention to myself. I could have been depressed, I just didn’t acknowledge it, or bother seeing it in the symptoms because I was too busy dealing with other things.” Another woman juggled the responsibilities of caring for her four children as a single mother who works full time. She was under duress due to several written warnings on the job. Nonetheless, she was motivated by the memory of having managed to fit in both her son’s therapy and her parenting classes in the recent past. Thus she concluded, “So if I did that, I can do this.”

Positive Motivators

Positive motivators were internal and external catalysts. The internal catalysts (urgency, inspiration to be a better parent, hope and desire for something better, and personal resolve) stirred unspoken forces and heightened the inner subjective voice within the women. The external catalysts (pathfinders and conditions paving the way) came from outside the women, but echoed what was within, moving them along the way. There were six such positive motivators.

Urgency

The women were aware that they “couldn’t stand it any more” and that they now needed to “move on” and “to move forward.” Thus, the desire for help included a time component in that the women knew that they needed help now. This knowing had three dimensions. First, the women knew that they were nearing the end of their staying power, as one woman said, “I just want to get over it.” Second, their distress had grown worse with the passing of time and thus they realized that it was unrealistic to trust that their mental health would improve with time alone. One said, “For the past two years and a half I’ve just kept it all in. It’s gotten worse. It’s not getting any better.” Third, the women saw the timeliness of the moment and knew that the present was an opportune time to change. Another woman said, “I know that I’ve been needing help for all these years and I think there’s gonna be a time where I’m going to break and instead of me finding that day without being able to find any resource, then why not deal with it now?”

Inspiration to be a better parent

Some women were inclined to enter therapy as a way to take better care of their children. One woman said her reason for getting help now was because “I’ve heard from my friends, from my doctor, and my mom, that being a single mother, I need to take care of myself so I can take care of my kids.” Another woman’s main concern was the rebellion of her teenage daughter (her only child). She said that her primary reason for enrolling in PWB was because “I wanna to help my daughter because I don’t wanna become my mother. I just don’t wanna do wrong things. I wanna do the right things.”

Hope and desire for something better

Despite the existing depression, women had hope that entering therapy would bring a better future and this prompted the women to take action. Women knew specifically what they were hoping to achieve in therapy. For example, one woman wanted to attain a state of equilibrium. She said, “I wanna be at peace with myself. I want tranquility. I want to feel content. That’s what I’m seeking.” Another woman remembered a time when her life was better and she was more efficient in daily tasks. She sought to restore her old self, “I want to understand and accept how I feel emotionally. I just don’t understand how I can feel all frustrated or not being able to get things done when I used to be able to do that.” The hope for feeling better was described by a third woman as a release from the numbness that had become comfortable after years of abuse, “I’ve grown too comfortable with these feelings that I have and sometimes it defines me. Sometimes I think maybe if I get rid of these feelings, I won’t be me. I would really like to feel something again.”

Personal resolve

The women’s words reflected their determination to achieve their therapeutic goals. For example, while denying suicidal ideation, a woman said, “Oh no, no, no. It can’t be that bad, cause I feel like whatever it is, there has to be a way. I know there’s always a way to figure something out, as long as I can get myself to the point where I can get it done. Cause I refuse to fall on my behind.” Another woman said, “There is no doubting myself in that I will follow through because I need the change in order to move forward.” Yet another woman acknowledged that therapy required the challenging and novel commitment to focus on herself. “I know that I want to stop, because I need to stop and take a break so I can actually do what I’m supposed to do. I know I have to relax because I have to actually pay attention to what I’m gonna do here. Now this is for me and it’s kinda hard to do.” Another said, “If I want to make a change and feel good, I have to put action into it.”

Pathfinders

Trusted people such as friends, family and various professionals including physicians, served as pathfinders who uncovered ways to enter therapy. One such pathfinder was a friend who provided transportation to the site for therapy. Another pathfinder was a friend (who was also a healthcare professional) who dispelled a myth about the definition of depression that previously blocked the woman from seeking treatment. This pathfinder informed the woman that she “didn’t have to cry every night to be depressed”. This crucial piece of information caused the woman to realize she was experiencing depression despite her lack of tears. This came as a surprise to the woman who, as a result of the conversation, was able to seek and enter therapy.

Several women were referred to PWB by friends who were already engaged in PWB. Thus, having a friend who was in treatment as a participant herself speak about the program’s benefits from personal experience and who recommended entering the treatment study, served as a strong positive motivator.

It is noteworthy that when the women described the pathfinders’ messages of encouragement, their descriptions were devoid of stigmatized language as if the pathfinders spoke with non-clinical, non-judgmental words. They used the phrase to “get help” rather than to “get therapy”.

Conditions paving the way

Certain conditions paved the way for the women to engage in the study with the nurse-therapist. The promise of flexibility in the treatment schedule was one such condition paving the way. Within the context of their busy and chaotic schedules, women voiced their needs for flexibility in scheduling appointments and responded when their needs were acknowledged and met. For example, the participants received an offer of free child care both for the initial meeting and for the therapy sessions. Although no woman used the free child care for Phase I, participants found the offer to be appealing when deciding to enter the treatment program. This served as a tangible indication of flexibility to accommodate the women’s needs.

Another condition paving the way was the research flyer. Several women associated the timing of receiving it and the message it conveyed with their own destiny. They considered it to be a powerful symbol that paved the way for them to enroll in PWB. One participant happened to receive the flyer right at a time when she desperately needed therapeutic help and claimed that seeing the flyer “was meant to be.” She and others found that the words on the flyer mirrored their inner state. As one woman said, “I remember the first line that it was kind of something that I always ask myself. I wonder if I’ll ever be free again. Free, because I’ve felt like this is not me.” The flyer actually stated “Wonder if you’ll ever feel good again?” but the message was tailored by the woman to replace the word “good” with “free”, giving insight into her inner reality.

Painful Motivators

The women were also motivated to enter therapy because of negative factors that functioned as catalysts to make the women take action because of the distress that they caused. The six painful motivators (aware of limits of coping alone, features of depression, visions for who I don’t want to be, relationships with partners, previous ways of coping no longer work, and past therapeutic encounters) were reflected in the pain of depression itself and stories of suffering.

Aware of the Limits of Coping Alone

The participants were aware of carrying the weight of a heavy burden on their own without support. In addition to owning the subjective feelings of depression, the women both wanted and needed someone to help them. One woman said, “I know I feel sad, I feel depressed, I feel helpless. I really need somebody to hear me out and to try to help me out.” Another woman echoed this saying, “I just realized I couldn’t do it on my own.”

Features of depression

The women reported symptoms and associated features of depression as painful but motivating. The symptom that was especially burdensome was the subjective experience of a depressed mood that does not go away. This was described as “sadness”, “distress”, feeling “incredibly numb” or “pathetic”. One woman described her experience by saying, “I wanna feel better. That’s why I am here too. I get so down. And it takes a lot. I have to be like really, really strong to get up and do things. It’s an awful feeling.” Another described a persistent inner struggle, “It just comes, and I’m like, ‘Yeah, I know’ and I’ll like put it off, but like a torment, it’s always there, every time I have a moment, I’m like, ‘There it is, there it is, there it is.’ I could be busy at work and then I’ll breathe, and there it is.”

In the wake of their demanding schedules women experienced a lack of productivity in daily tasks; a state of “not getting things done” compared to their old usual self. One woman spoke about simultaneously feeling unproductive and confused. “I feel like I’m not going anywhere. I feel like ‘What else should I be doing?’ I feel like ‘How can I do things?’ I feel like I don’t know how to go about things.” Another spoke about the frustration of failing to meet her children’s needs, “My little ones, they need me, and they need some things done, but I’m not getting things done. I don’t even know where to start anymore. I need to be able to get my things done for me and my kids. That’s a priority, so I can be okay and my kids can be okay.”

Other features of depression were vegetative symptoms such as weight loss and oversleeping. For example a woman said that her main reason for seeking help was “Because I was feeling like things changed for me as far as my eating habits. Everybody notices the weight loss. Everybody would be like, ‘Oh my God, what’s going, what happened to you?’, and it’s like ‘Ok, shout in my face.’ Like I, I already, you know, like I don’t know.” Others were also motivated by “hibernating” or oversleeping, coupled with a lack of desire to “deal with anybody or anything.”

Even as the women complained of symptoms of depression, they were capable of recognizing these features as abnormal and used them as a motivator to seek help. One woman described her array of symptoms saying, “I’m tired. I’m angry with myself, a lot of extreme anger. I gained weight and I am having more problems with my parents than I usually have.” She subsequently said, “I have been dealing with depression, the same BS for years. I guess I was in denial. That’s not normal. That’s not healthy.”

Visions for who I don’t want to be

The women expected that, if left untreated, the depression would turn them into someone who they do not want to be or did not want others to see. For example, one woman was motivated to not become an “alcoholic” because she said, ”my dad’s like that. That gets me nowhere.” Furthermore, this woman also did not want the depression to worsen because she envisioned what her depression would do to her mother. She knew she would feel guilty for giving in to a desire to stay in bed for two to three consecutive days and said, “I couldn’t allow my mom to see me that way. I mean, she would ask me. I would be putting up a façade.”

Observations from others served to validate the severity of negative traits being demonstrated. One woman explained, “I started noticing and my friends were telling me, I’m [you’re] obsessed. ‘You’re gonna end up in a psychiatric ward if you don’t do something about it.’ My friends said I’m really turning into this psycho chick that I’m not supposed to be.” The poignancy of feedback from others was powerful. When a friend from high school described a woman as “pathetic”, she reported it as “a stab to the heart.”

Relationships with partners

The women were frequently motivated to get help because of the tensions involved in ending meaningful, but difficult and complicated relationships with partners. One woman was extracting herself from a marriage of six years to the father of her two children. She described the man as someone who tried to pressure her when she wanted to leave. She reported that he purposefully “cut himself a bazillion times, so there’d be a lot of blood” so she would be compelled to take care of him and would not leave the relationship. Also, his behavior involved infidelity and accusations of infidelity. She said that she was “a kid” when they met at 16 years of age which made it even more difficult to separate from him. The contradictory feelings of “crazy, crazy love” and “so much anger” kept her stuck in the past while living in the present. She desired detachment but letting go brought confusion. She said, “I still love him, I love him to death. I wish I could just let go, and then I wouldn’t be as sad as I am, but I can’t. I still want to be part of him and his family.”

Another participant expressed her motivation to work on separating from her husband of eight years. She left him four months ago but the separation did not work out as she thought it would because, as she said, although “it was my choice, he moved right on with another woman. I was expecting another outcome. He’s 36 and she’s only 21, this girl.” Then her ex-husband told the participant’s children to lie about his relationship with the new girlfriend. When it finally became real that he had moved on, she told herself, “I’m sad. I feel like I failed, like I made the wrong choice,” despite her certainty that she wanted to move on.

A third participant reflected on the many complications of letting go of the father of her children, a substance abuser, who continually came back asking for her help. “I hate myself from being who I am now, because of all this. I don’t want to feel like I need to help him ever again. He don’t deserve it.”

Another woman’s partner had left her and she responded with a compulsion to “stalk” him. She said, “This year it got to the point where he wants to put a restraining order on me.” The possibility of a restraining order shocked her and motivated her to seek help.

Another participant’s husband of 24 years and father of her six children, was deported by the government. In the interview, she admitted she finally became free to get help after he left the country because he kept her from getting treatment. She said, “I wanted to get counseling but my husband wouldn’t let me because he believed that there was no way to help. He said nobody could help me.” Although she believed him at the time, she now knew that help was possible.

Previous ways of coping no longer work

The women discovered that their old practices for coping via self-expression, were no longer useful. This had two dimensions. First, women had expressed feelings verbally to confidantes but they found that this was no longer effective. One woman said, “Even true blue friends have their own thing going on and my story is getting old. I don’t wanna like put it on them. I’m always talking about the same thing.” Another woman spoke about no longer feeling free to confide in friends when she said, “When I have my episodes, crying myself a river, I usually call like three friends. So I look for help from my friends, but friends can only do so much. My friends got fed up of listening to me. I got fed up repeating myself.” Another woman described others who used to be helpful as now being judgmental. “People tell me I make too much of nothing. I don’t feel that way. I feel like if there’s an issue, I wanna address it. I don’t wanna just let it go.”

The second dimension of “coping that no longer worked” is related to the expression of feelings in written form by journaling. One woman said that she started journaling at age 15 and now has “four notebooks full of everyday entries, but a girl gets tired after awhile. People say it should do me good, but I don’t feel a difference.” Similarly, other participants felt journaling was no longer helpful.“ Journaling was a way of dealing with it, a therapy, but now I realize I can’t do it no more.”

Past therapeutic encounters

Some women had previously been in therapy, but reported these efforts to be unproductive. Nonetheless, these experiences actually served as motivators for seeking help because the women did not get what they needed therapeutically and were left wanting. One woman remembered having one session with a school psychologist in high school but described it as not helpful “because she (the therapist) was just throwing negative things at me.” Later, this participant saw the psychologist at her community college, but it also was unproductive. “She just gave me a sheet of where you can seek help. I had to pay and I wasn’t sure if I still had MediCal”. Another woman recalled having had a few family therapy sessions before PWB and explained, “but I don’t think it’s working or it’s working fast enough. It’s so hard to get appointments and then she cancelled one time and it’s every two weeks.” She added “I don’t feel that I’m being helped” which was why she wanted to enter PWB. It is noteworthy that none of the women described a traumatic experience with a previous therapist. The past unproductive but not traumatic experiences with therapy, combined with the positive motivators, spurred the women on to try yet another therapist in PWB.

Discussion

The dynamic interaction between positive and painful motivators provided the forward momentum that led the 12 low-income, second generation Latinas of this sample to seek therapy for depression. Although the women were not explicitly aware that their comments and stories contained an interplay of both positive and painful motivators, their responses were filled with anticipations that beckoned them forward (positive motivators) and negative experiences that they wanted to leave behind (painful motivators). While both were powerful, it was the positive motivators that built anticipation for desirable results and provided the vision for how therapy could happen. This made the notion of therapy possible.

The interplay of motivators was not perceived as a chronological experience or a stepwise process leading to a breaking point, but as a constellation of factors experienced simultaneously. The women spoke about various factors that contributed to their readiness and their commitment to follow through with therapy. For example, they felt that they could no longer cope alone and they felt the urgency for therapeutic help. But, simultaneously, they were exasperated from the persistent features of depression that decreased their productivity because efficiency was a necessity in their demanding, everyday lives. The synergy of these factors provided the momentum for getting help.

While positive and painful motivators were important, the issues of self and time complicated the entire process. Indeed, the women of this sample, all of whom struggled with depressive symptoms, had a tendency to neglect their own “selves” and over-focus on others’ needs and agendas. Alice Miller (1997) associated depression with the denial of the true self. She poignantly described the lack of fulfillment experienced when doing for others is an unconscious attempt to compensate for the inner loneliness of a false self. The women of our sample knew that their unsettled, unfulfilled feelings were devoid of self acceptance. However, at the time of entering PWB, some women realized that therapy held benefits for their children which provided an easier way to justify getting therapy for themselves. The tension between denying and becoming aware of the needs of the self complicated the women’s experiences of the various catalysts. The topic of Latinas’ hesitancy to put their own needs first has been of interest in the popular press targeting Latina readers (Gil & Vasquez, 1996).

Most of the women lived with chaos or had lived in chaotic circumstances for many years. Their overbooked schedules showed that they were doers and copers, active mothers taking care of their families, finances, school schedules, in-laws, work responsibilities, and current or estranged partners. The women came in saying they did not have time for even one session of therapy, but simultaneously foresaw that eight sessions would not be enough to alleviate all their problems. In recognizing the reality that time was a significant issue, the women were not complaining. Instead, they were making explicit the complication of time, voicing the doubt of where in their busy lives they would find adequate hours to engage in what seemed to be an enormous, time-consuming feat. However, the phenomenon of “time” as a complication may be due to symptoms of depression such as fatigue, hopelessness, and cognitive slowing that can cause depressed persons to become susceptible to the stress of what Zuckoff, Swartz, and Grote called the “time and hassle factors” of help seeking (2008, p. 110).

Despite the complications of self and time, each woman came to the Phase I interview with a strong recognition that something was seriously wrong with her life and emotional state. The women recounted the experience of seeing the flyer and realizing that the words echoed their inner state. The synergy of the written word with their inner experience was meaningful and added motivation to get help. While studies show that Latinos delay help-seeking for depression because they do not recognize the symptoms (Givens, et al., 2007; Zuvekas & Fleishman, 2008), the flyer for this study served to synchronize the women’s conscious awareness of both their problem and an opportunity to solve it. They foresaw an ugly and unwanted future without therapy, and decided to take action.

Although the nurse-therapist was prepared to encounter resistance during the Motivational Assessment, none of the women stated any hesitancy to engage in therapy. Even though they had previous negative experiences with therapists, the women engaged in the interview with purpose and hope for a fruitful outcome. It is possible that ambivalence present at the start of the interview had dissipated or was resolved during the SCID and Motivational Assessment. It is likely that the use of MI-techniques throughout the interview combined with the nurse-therapist’s sensitivity to various factors unique to the social, cultural, and economic situations of second generation Latinas, were associated with this lack of resistance. It is also possible that this sample happened to have little resistance to begin with.

The known association between marital disruption and mood disorders (Kessler et al., 2005) was manifest in the narratives of women in our sample. Women spoke with personal resolve to heal even in the midst of intensely painful relationships with partners or ex-partners. These relationships were complex, mixing love and loyalty with defeat, betrayal, manipulation, criminal activity, lack of support, abuse, or neglect. Without denying the pain involved, the women did not blame their partners. Instead, the women admitted the relational complexities while expressing their hopes for favorable outcomes from therapy. The stories of personal resolve showed that the women knew that action was required even while coping with heartbreak. This is similar to the findings of other research that shows low income, minority women often seek mental health care after a loss or conflict in their relationships (Wang, Lane et al., 2005). Therapy takes effort and the Latinas of this sample were determined and committed to do the work required and move on.

Women helping women was a potent dynamic that cross-cut the painful and positive motivators. The input from mothers, female friends, neighbors, and sisters had a motivating effect. Whether harsh or loving, they validated the severity of the women’s problems. They scolded, they shared knowledge, and they refused to listen to repeated complaints or ruminations of problems previously discussed. Even the stigmatizing judgment of one woman to another (referring to her as a “psycho-chick”) served as a motivator, albeit painful, and added momentum towards professional therapy.

Another way that women helped women was via the role-modeling done by those who already were enrolled in PWB. Their willingness to share about their experiences in therapy was powerful on different levels. It de-stigmatized therapy and gave women permission to take action by sharing personal issues with a stranger (i.e., the nurse-therapist). Their example showed others that they did not have to solve their problems on their own. Such an expectation of self-sufficiency has been found to be a deterrent in help-seeking for depression in primary care (Wells et al., 2008). Gil and Vasquez (1996) point out in their self-help book for Latinas that tradition expects women to refrain from asking for help or discussing personal problems with others.

Our findings hold implications for clinical practice. The fallacy that Latinas wait until they reach a breaking point before they access effective treatment for depression needs to be challenged. Nurses, health educators, and other healthcare providers are in prime positions to do this. Furthermore, flexibility with scheduling appointments holds promise for attracting Latina patients. Therefore, continuing to work to overcome system barriers and practical difficulties to achieve this flexibility is key. When discussing stigmatized topics such as depression with Latinas, the current research showed that the techniques of MI can be very useful. Further exploration is warranted on the effectiveness and possibilities of MI-techniques for engaging Latinas in discussions about emotional well-being in clinical mental health and non-mental health settings. In conclusion, our data show that low income, second generation Latinas with depression had unique needs and complex lives. However, cultural sensitivity to the complexities of second generation, low income Latinas’ lives gleaned from this study, provides helpful insight for enhancing access to mental healthcare.

Acknowledgment

The work was funded through the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant # NR 008928 K23

Footnotes

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the participants of this study and to Jeanne Miranda, PhD for her input on the design of this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, Ortega AN. Mental health care for Latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H, Burke BL. Motivational interviewing as an integrative framework for the treatment of depression. In: Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick G. Spanish Train. Santa Monica, CA: Oil on linen; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJA, Burns DD. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depression: Challenges for the delivery of care. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:583–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 Disorders (SCID - I/P, Verion 2.0, 4/97 revision) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gil RM, Vazques CI. The Maria Paradox: How Latinas can merge old world traditions with new world self-esteem. New York: Berkley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Frederick SS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican- Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, Zhang L, Liao D, Duan N, Wells KB. Disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and site of care. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:1517–1523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pincay IE, Guarnaccia PJ. “It’s like going through an earthquake”: Anthropological perspectives on depression among Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. The drama of the gifted child: The search for the true self. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. (2nd Ed.) New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health preferences among low-income and minority women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda VD, McGuire TG. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in use of outpatient mental health and substance use services by depressed adults. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2006;77:211–222. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Sribney WM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kolody B. 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among Mexican-Americans: Nativity, social assimilation, and age determinants. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2004;192(8):532–541. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135477.57357.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve- month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB. Overcoming barriers to reducing the burden of affective disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;15:655–675. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckoff A, Swartz HA, Grote NK. Motivational interviewing as a prelude to psychotherapy of depression. In: Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Fleishman JA. Self-rated mental health and racial/ethic disparities in mental health service use. Medical Care. 2008;46(9):915–923. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817919e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]