Abstract

Epiretinal prostheses are designed to restore functional vision to the blind by electrically stimulating surviving retinal neurons. These devices have classically employed symmetric biphasic current pulses in order to maintain a balance of charge. Prior electrophysiological and psychophysical studies in peripheral nerve show that adding an interphase gap (IPG) between the two phases makes stimulation more efficient than pulses with no gap. We investigated the effect of IPG duration on retinal ganglion cell (RGC) electrical thresholds in salamander retina, as well as phosphene perceptual thresholds in epiretinal prosthesis patients. In general, there was a negative exponential correlation between threshold and IPG duration. Durations greater than or equal to ~0.5 ms reduced salamander RGC thresholds by 20–25%. Psychophysical testing in five retinal prosthesis patients indicated that stimulating with IPGs can decrease phosphene perceptual thresholds by 10–15%. Results from Hodgkin-Huxley-type simulations of RGC behavior corroborated the observed behavior. Incorporating interphase gaps can reduce the power consumption of epiretinal prostheses and increase the available dynamic range of phosphene size and brightness.

1. Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a degenerative disease of the outer retina that causes progressive vision loss and eventual blindness [1]. The Argus II® Retinal Prosthesis System (Argus II) is the only long-term therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for individuals with RP who have bare or no light perception. This device uses an implantable multielectrode array (MEA) to electrically stimulate surviving neurons in the inner retina, thus creating the sensation of vision. Images acquired by a head-mounted camera are downsampled, converted to a series of stimulus pulses, and delivered to the MEA [2].

Most neural implants, including the Argus II, stimulate with symmetric biphasic current pulses. The leading phase, typically the cathodic phase, injects charge in order to evoke neural responses. This is followed by the anodic (trailing) phase, which balances charge and reverses electrochemical processes. The net charge applied to the electrode should be virtually zero, since accumulation of charge can lead to hydrolysis and gas bubble formation. A given electrode material will have a charge injection limit that dictates the amount of charge per phase that can be delivered safely, without causing irreversible damage to the electrode and surrounding tissue.

Argus II electrodes are coated with platinum grey, which has a published safety limit of 1 mC/cm2 for acute stimulation and 0.35 mC/cm2 for chronic stimulation [3–5]. A recent study in 30 Argus II recipients found that nearly half of all enabled electrodes did not have measurable thresholds below the acute safety limit [6]. Thus, there exists a strong need to reduce Argus II stimulation thresholds.

One approach for reducing thresholds is to minimize the distance between the MEA and retina. In Argus II patients, electrodes farther from the retina and/or macula generally require more stimulus current to evoke visual phosphenes [4, 5]. Because the array is affixed to the retina with a single retinal tack [6, 7], it is often difficult to obtain a tight MEA-retina interface. This is due to a number of factors, such as intersubject variability in eye curvature. Even when electrodes contact the macula directly, an average of 1 in 10 still have thresholds above 1 mC/cm2 [4, 5].

In this study, we investigated an alternative method for reducing retinal stimulation thresholds that relies only on a modified stimulus pulse shape. A drawback to using biphasic pulses is that the trailing phase partially opposes the neural depolarization induced by the leading phase, thereby increasing the stimulus amplitude needed to evoke neural spiking. Prior studies have found that adding an interphase gap (IPG) between the two phases (see figure 1(A)) reduces this effect. Interphase gaps have been used to decrease electrical thresholds in auditory nerve [8, 9] and motor nerve [10, 11], as well as perceptual thresholds in cochlear implant patients [12, 13]. IPGs were also used by the Argus I (the Argus II’s predecessor) [14–16], though a formal study of their effect was never conducted.

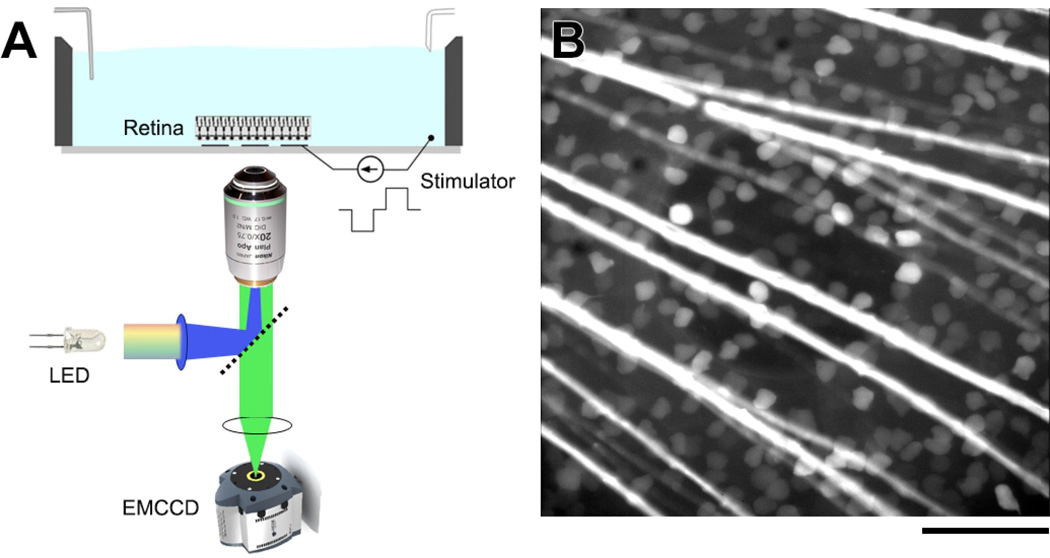

Figure 1.

(A) Experimental setup used to image RGC calcium fluorescence in ex vivo salamander retina. Images were captured with an electron-multiplying CCD camera during stimulation with a single MEA electrode. (B) Fluorescence image of a salamander retina loaded with OGB-1 dextran and mounted on a transparent MEA. RGC somata and axon bundles are clearly visible. A 200-µm-diameter indium-tin-oxide electrode is centered in the field of view. Scale bar is 100 µm.

We determined the effect of interphase gap duration on retinal stimulation thresholds using a combination of animal electrophysiology, computational modeling, and human subject testing. Calcium imaging was used to measure retinal ganglion cell (RGC) activity in isolated salamander retina during stimulation with different IPG lengths. Hodgkin-Huxley-type models of salamander and cat RGCs were developed to further study the effect of IPG on ganglion cell thresholds. Finally, psychophysical testing was performed in five Argus II subjects to measure the effect of IPG duration on phosphene perceptual thresholds. Data from all three experiments consistently showed a significant decrease in thresholds when stimulating with interphase gaps.

2. Methods

2.1 Animal Electrophysiology

We used calcium imaging to monitor RGC spiking activity in vitro during electrical stimulation. Larval tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) RGCs were labeled with the fluorescent calcium dye Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) dextran (10 kDa; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) using a retrograde loading technique developed in-house [17]. Briefly, eyes were enucleated and hemisected with a razor blade. The optic nerve was trimmed to 0.5 mm in length, and a small segment of polyimide tubing was glued around it to create a chamber encircling the nerve stump. OGB-1 dextran (1.5 µL, 20 mM) was pipetted into the chamber to cover the exposed cut ends of the RGC axons. The eye cup was then placed in a perfusion chamber for 4–6 hours to allow retrograde diffusion of the dye into RGC somata.

Following dye loading, the retina was removed from the eye cup, mounted ganglion cell-side-down on an MEA, and superfused with physiological saline. Superfusate contained 110 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 30 mM NaHCO3, and 10 µM EDTA, equilibrated with 5% CO2/95% O2 gas, and adjusted to pH 7.4 and 270–275 mOsm. All recordings were performed at room temperature. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Southern California (USC). Salamanders (n = 5; Charles D. Sullivan Co., Inc., Nashville, TN) were maintained at 6–8 °C until use and euthanized by rapid decapitation and pithing.

Multielectrode arrays were fabricated by the authors at the W.M. Keck Photonics Laboratory at USC as described previously [18, 19]. Arrays were constructed from thin, transparent materials for imaging purposes. Fluorescence excitation was provided by a super bright white LED and filtered through a Semrock (Rochester, NY) filter set (#FITC-3540B). Emission light was collected by a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Plan Apo 0.75 NA 20x inverted microscope objective and imaged with an Andor (Belfast, Northern Ireland) Ixon electron-multiplying CCD camera. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the experimental setup (A) and a fluorescence image of a stained salamander retina mounted on an MEA (B).

Electrical stimuli were delivered via a transparent disk electrode while recording epifluorescence image series at 10 Hz. Electrode size (200-µm diameter) and pulse width (0.46 ms/phase, cathodic-first) were chosen to match those of the Argus II [4, 20]. Interphase gap duration was varied between 0.12 ms (26% of pulse width) and 1.84 ms (400% of pulse width) to study the effect of duration on threshold (see table 1 for the list of IPG durations). Percent change was used to compare each cell’s threshold at a particular gap length to its threshold when no IPG was used. As a control, we ran two trials with no IPG in a single animal to investigate repeatability of the threshold measurement.

Table 1.

Comparison of stimulation parameters used in the salamander and human experiments.

| Salamander | Human | |

|---|---|---|

| IPG Durations (ms) | 0, 0.12, 0.24, 0.34, 0.46, 0.92, 1.38, 1.84 | 0, 0.15, 0.46, 1.0, 2.0 |

| Pulse Width (ms/phase) | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| # of Pulses per Burst | 30 | 30 |

| Pulse Frequency (Hz) | 167 | 120 |

| Electrode Diameter (µm) | 200 | 200 |

| Thresholds | Electrical | Perceptual |

Stimuli consisted of high-frequency bursts, in order to evoke a train of spikes needed to generate a detectable calcium transient [17]. Each stimulus (30 pulses, 167 Hz) was delivered 25 times on 2-second intervals and repeated over 10 monotonically increasing amplitudes. Electrically evoked responses were detected by convolving the fluorescence intensity of each cell body with a difference filter and identifying rapid changes in fluorescence temporally correlated with the stimuli. A dose-response curve was generated for every RGC by plotting the fraction of the 25 stimuli that elicited a response at each amplitude. A sigmoidal function was fit to this curve, and threshold was defined as the amplitude that yielded a 50% response. All post-processing steps were performed in ImageJ 1.43u (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and MATLAB R2009b (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Statistical significance was determined with unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA using a significance level of 5%.

2.2 Computational Modeling

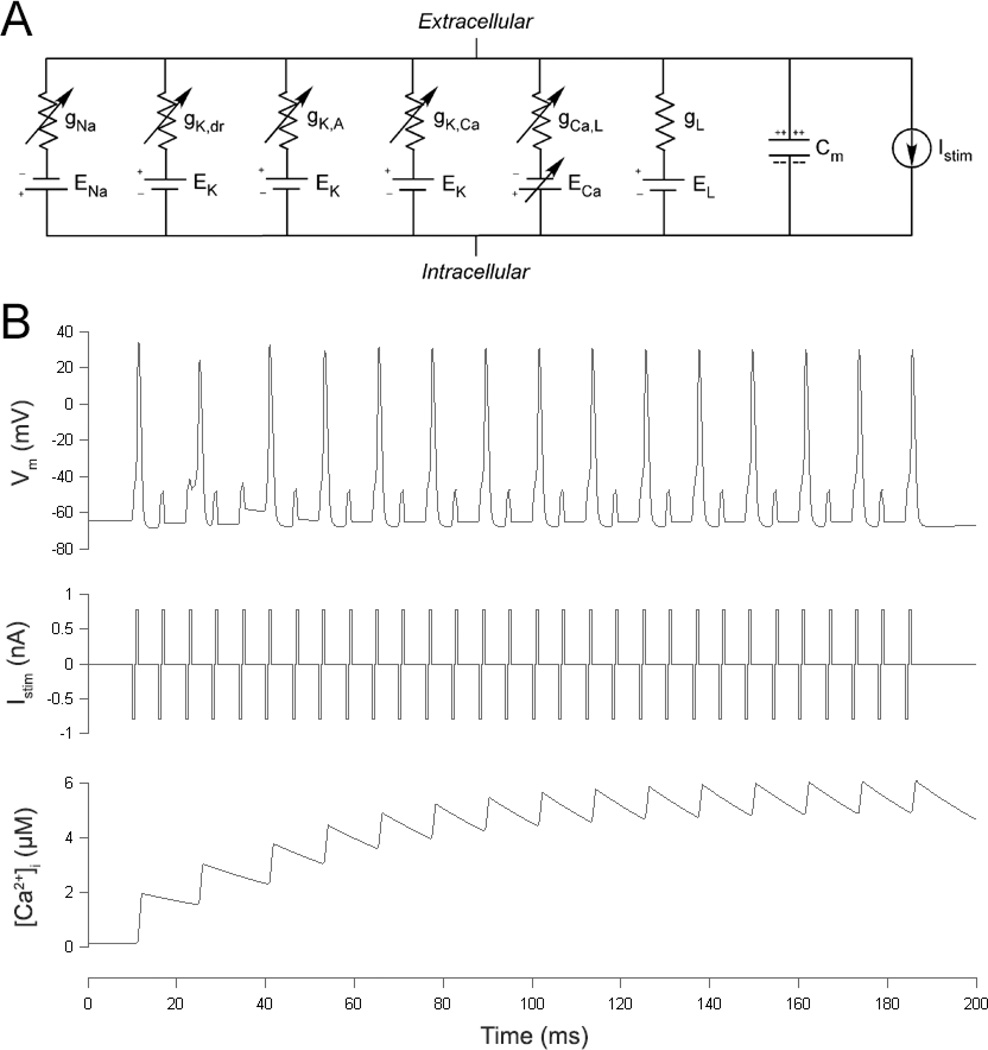

We built Hodgkin-Huxley-type models to further study the effect of IPG on ganglion cell electrical thresholds. Equations and parameters were taken from prior physiology and modeling studies of tiger salamander [21, 22] and cat [23] RGCs. As shown in figure 2(A), the salamander model incorporates four types of voltage-gated ion channels (Na+, delayed rectifier K+, A-type K+, and L-type Ca2+), as well as Ca2+-activated K+ channels. The cat model includes these same channels in addition to N-type Ca2+ channels. Differential equations for membrane voltage (equation 1) and intracellular calcium concentration (equation 2 for salamander; equation 3 for cat) were solved in MATLAB using the forward Euler method with a time step of 0.01 ms. Current clamp was used to simulate extracellular stimulation.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where F = the Faraday constant, = surface area-to-volume ratio of the cell, 2 = valence of calcium, [Ca2+]res = residual calcium level, and τ = time constant of calcium removal/sequestration.

| (3) |

where fi = fraction of free calcium in the cytosol, Vcell = volume of the cell, and jpump = loss of calcium due to Ca2+ pumps.

Figure 2.

(A) Components of the Hodgkin-Huxley-type model include four types of voltage-gated ion channels (Na+, delayed rectifier K+, A-type K+, and L-type Ca2+), Ca2+-activated K+ channels, leak channels, a membrane capacitance, and a current stimulation source. N-type Ca2+ channels (not pictured) were included only in the cat model. (B) Membrane voltage (top) and intracellular calcium concentration (bottom) of a model salamander RGC in response to a stimulus burst (middle). Fifteen of the 30 stimuli in the burst evoked action potentials, a condition that was defined as threshold.

The models’ stimulation parameters were set to match the experimental conditions as closely as possible. A burst of 30 pulses was delivered at 167 Hz. Pulse width was 0.46 ms/phase, and IPGs ranged from 0.12 to 1.84 ms. Membrane voltage was calculated in response to each stimulus burst. Action potentials were identified as peaks in the voltage that exceeded 20 mV (salamander) or 30 mV (cat). Threshold was defined as the minimum stimulus amplitude that caused at least 50% of the pulses in the burst to elicit spikes. Figure 2(B) shows the membrane potential (top) and intracellular calcium concentration (bottom) of a modeled salamander RGC, computed in response to a stimulus burst (middle) at threshold. As was the case with the animal experiments, threshold at a particular IPG length was compared to threshold when no IPG was used.

2.3 Human Subject Testing

The effect of interphase gap on perceptual threshold (the current required to evoke a phosphene) was measured in five Argus II subjects. Subjects were recruited from two clinical centers (Doheny Eye Institute at USC, Los Angeles, CA; Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Informed consent was obtained from every patient, and all procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the USC Institutional Review Board and was part of the FDA-approved Investigational Device Exemption clinical trial of the Argus II device (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00407602).

Stimulation parameters used for human testing were similar to those used in the salamander experiments (table 1). Each stimulus was a burst of 30 pulses delivered at 120 Hz (the maximum allowable frequency of the Argus II). Pulse width was fixed at 0.46 ms/phase, and IPG was varied between 0.15 and 2.0 ms in a random order. Pulses containing no interphase gap were also presented in order to obtain baseline thresholds. The time between the start of one threshold measurement and the start of the next was generally less than 5 minutes.

Two electrodes were tested in each patient. Electrodes were chosen based on prior knowledge of their thresholds; we selected electrodes with relatively low thresholds to limit the possibility of exceeding electrochemical safety limits as patients adapted to stimulation (see below). Thresholds were determined with a staircase procedure. Briefly, a subthreshold stimulus (4 µA) was applied, and amplitude was gradually increased until the patient reported seeing a phosphene. Amplitude was then stepped up by 50 µA and gradually reduced until the phosphene disappeared. Finally, amplitude was gradually increased again until the patient reported another phosphene. The amplitude at which the phosphene reappeared was defined as threshold.

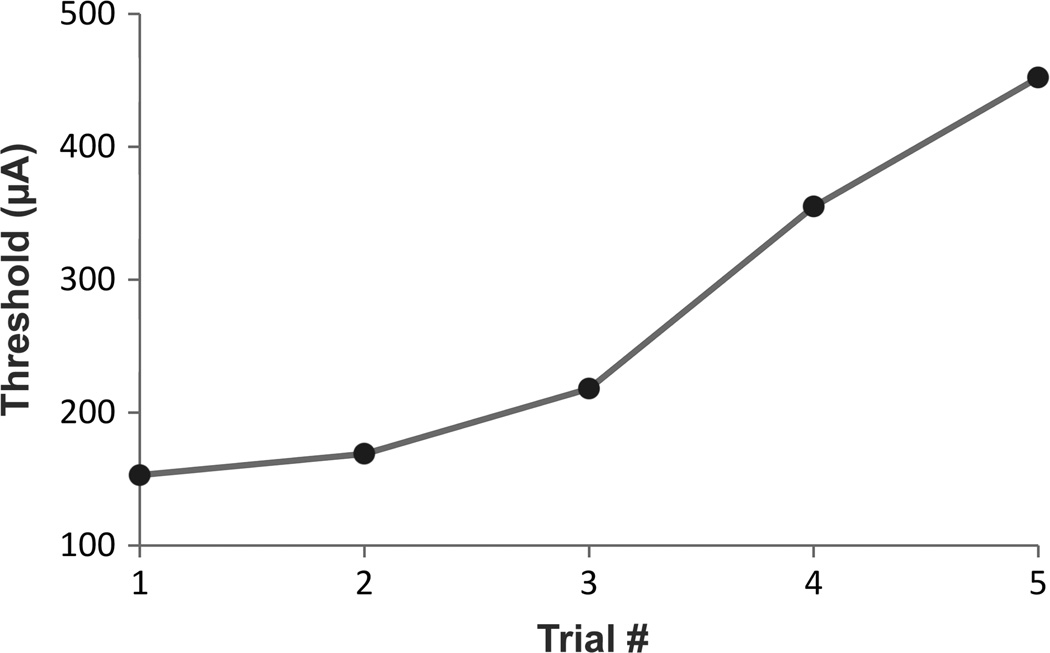

Initial testing with one patient revealed that thresholds gradually rose during the course of the test session, suggesting a temporary adaptive physiological mechanism (figure 3). Adaptation was problematic because it masked any possible threshold-lowering effects of IPG. To overcome this, we used a bracketing technique in which each IPG threshold was measured between two stimulus trials with gapless pulses. The effect of IPG was then determined by comparing the threshold measured from the IPG stimulus to the average of the two thresholds measured when no gap was used. (For example, the order of IPGs tested in a patient might be: 0 ms, 1.0 ms, 0 ms, 0.15 ms, 0 ms, 2.0 ms, 0 ms, 0.46 ms, 0 ms.) After implementing this method, the effects of interphase gap on perceptual thresholds became much more pronounced.

Figure 3.

Threshold adaptation in an Argus II patient. Five threshold measurements were performed with identical pulses containing no interphase gap. Thresholds steadily rose over time, indicating that responses were becoming desensitized.

2.4 Curve Fitting

All curves were fit with decaying exponentials (equation 4). Fits were weighted with the reciprocal of the variance and were optimized to minimize the sum of squared error.

| (4) |

where Δthresh = change in threshold vs. no IPG, tIPG = IPG duration, τ = decay time constant.

3. Results

3.1 Animal Electrophysiology & Computational Modeling

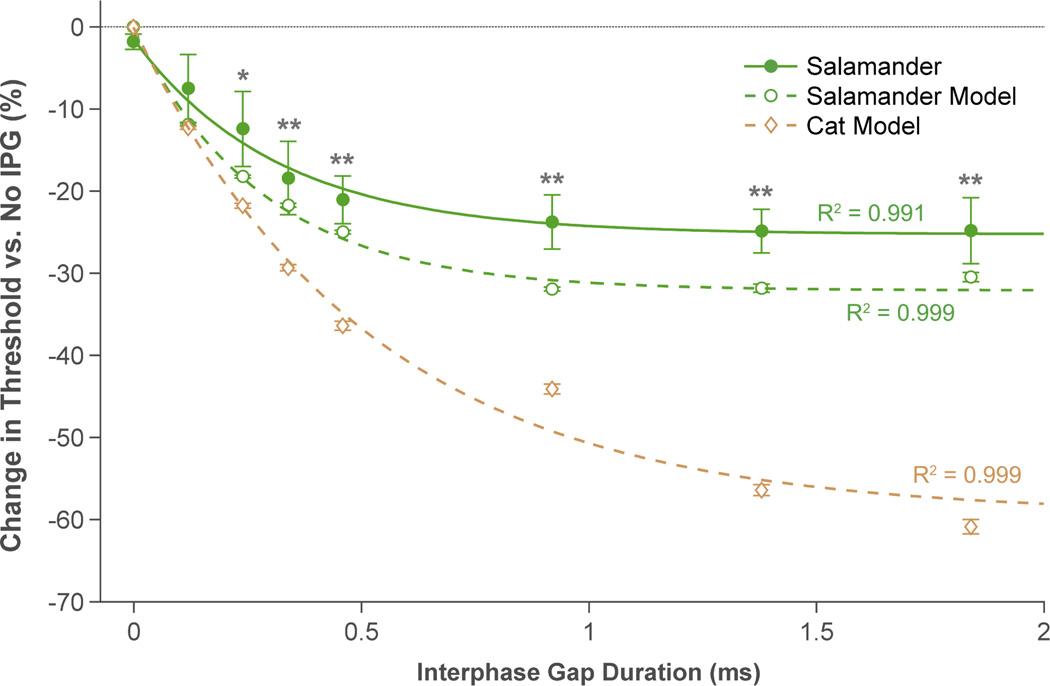

Figure 4 summarizes the effect of IPG duration on RGC electrical thresholds for the animal experiments and computational models. In general, longer interphase gaps led to lower thresholds, though only to a certain extent. In the animal experiments, IPG durations 0.24 ms and longer caused a statistically significant reduction in threshold versus no IPG (P < 0.05). With an IPG duration equivalent to the pulse width (0.46 ms), RGC thresholds were 21.1 ± 13.9% lower than when no gap was used (P < 0.01). Gap lengths longer than 0.46 ms further decreased thresholds but only marginally: With 0.92-, 1.38-, and 1.84- ms gaps, mean change in threshold fell by only an additional 3.8%. Pulses with gaps shorter than 0.46 ms were less effective at stimulating RGCs. For example, an IPG duration of 0.24 ms (52% of pulse width) lowered thresholds by only 12.4 ± 16.4% versus no gap (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of interphase gap duration on ganglion cell electrical thresholds. Data from five salamander retinas (closed circles) indicated that IPGs reduce thresholds by up to ~25%. Computational modeling also predicted the threshold-lowering effects of IPG. Two models were generated: one for a salamander RGC (open circles) and another for a cat RGC (diamonds). Each model was solved 100 times while adding 10% uniformly distributed pseudorandom noise to the model parameters (data points show mean ± SEM of the 100 iterations). The salamander model aligned much more closely with the animal data. Decaying exponentials (equation 4) were fit to each data set. The best-fit parameter values are provided in table 2. Error bars indicate SEM. * means P < 0.05, and ** means P < 0.01.

Repeatability of the threshold measurement was assessed by performing two identical stimulation runs with no IPG 40 minutes apart. RGC thresholds between these two trials varied by −1.8 ± 11.3%, indicating that the effects of IPG are likely due to the gaps themselves, rather than trial-to-trial variability. The standard deviation in repeatability provides an estimate for the noise in the measured threshold of each RGC. Its relatively large value may be a consequence of fluorescence photobleaching, ganglion cell desensitization [24, 25], and/or pooling data from multiple RGC subclasses.

Consistent with the animal data, the computational models also predicted lower thresholds with longer interphase gaps. The effects of IPG were more pronounced in the cat model than in the salamander model, especially with longer gap lengths (see figure 4). As anticipated, predictions from the salamander model were more in line with the experimental data (also from salamander retina). Adding 10% uniformly distributed pseudorandom noise to the model parameters had minimal effect on predicted threshold changes.

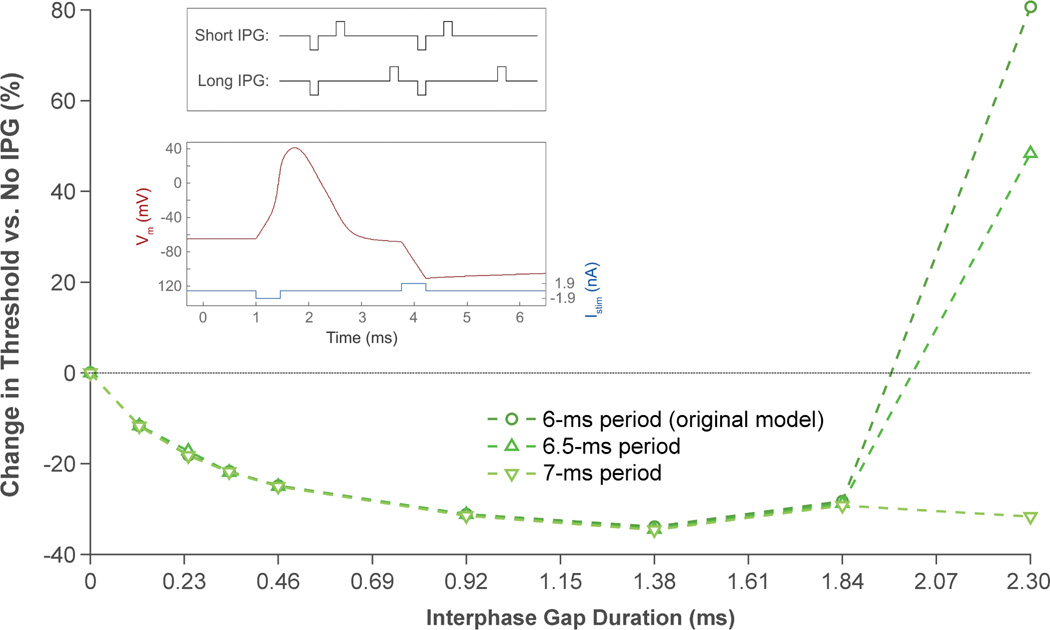

The salamander model revealed an interesting behavior that may have implications for high-frequency stimulation with long IPGs. As shown in figure 4 (open circles), 1.38-ms gaps were more effective at stimulating the model RGC than 1.84-ms gaps. We hypothesized that this was due to interactions between successive pulses; as IPG becomes longer, pulses become closer in time (figure 5, top inset). This causes a blocking effect, in which the anodic phase of one pulse hyperpolarizes the cell membrane, thus raising the threshold of action potential initiation for the next pulse [13, 26, 27].

Figure 5.

Modeling the effect of stimulus frequency and IPG length on anodic block. The blocking effect is most pronounced when pulses are spaced close together (i.e., at high frequencies and long IPG durations). The bottom inset shows how the cell membrane is hyperpolarized by the anodic phase of the stimulus pulse. Data were generated from the salamander model.

To test this hypothesis, we solved the model using lower stimulation frequencies (154 and 143 Hz), spacing pulses farther apart in increments of 0.5 ms (figure 5). As expected, the blocking effect was present only with longer IPG lengths and was reduced as stimulus frequency decreased. By solving for the membrane voltage of the modeled cell in response to a single biphasic pulse, it became clear that the anodic phase was hyperpolarizing the cell membrane (figure 5, bottom inset).

3.2 Human Subject Testing

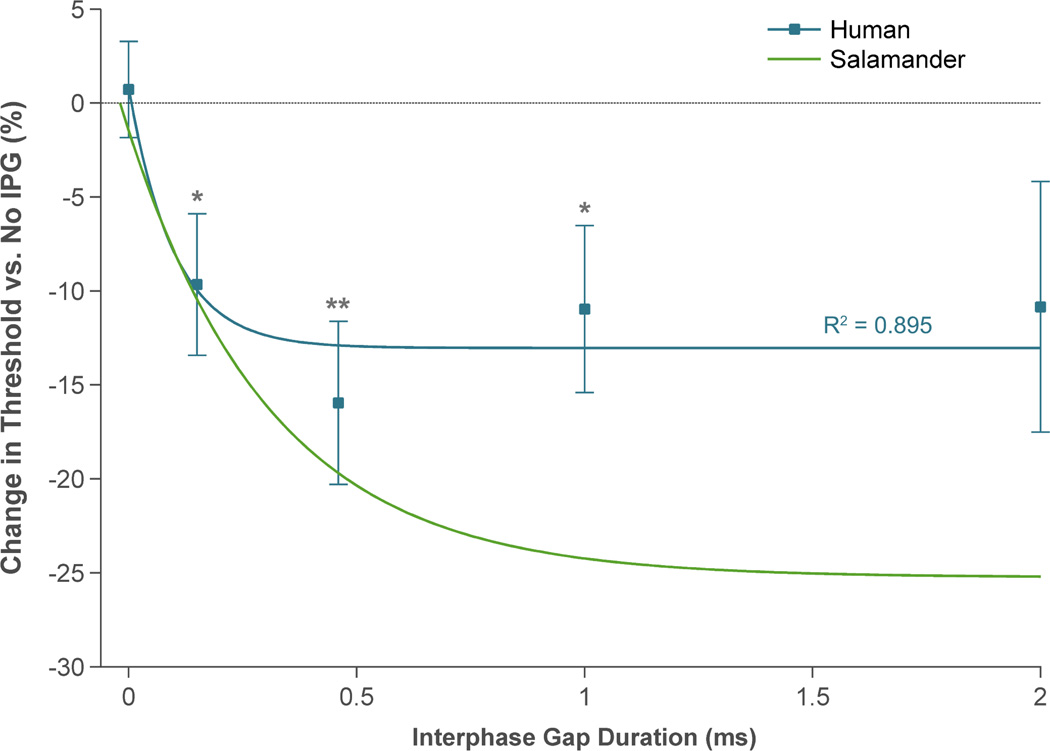

Psychophysical testing was performed in retinal prosthesis patients to determine how IPG duration affected phosphene perceptual thresholds. Data were acquired from five Argus II subjects, using two electrodes per subject. After controlling for effects of adaptation to repeated stimulation (see section 2.3), it became evident that IPG had a similar effect on perceptual thresholds as it did on RGC electrical thresholds. Figure 6 (blue squares) shows how perceptual thresholds changed as IPG length was varied between 0 and 2 ms. Regardless of length, there was a ~10–15% reduction in thresholds compared to gapless pulses. These reductions were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all IPG durations except 2 ms (possibly due to anodic block). ANOVA indicated that each IPG duration we tested had a statistically similar effect on threshold (P = 0.81).

Figure 6.

Effect of interphase gap duration on perceptual thresholds in five Argus II subjects (blue squares). Data were fit with a decaying exponential (best-fit parameter values are given in table 2). Results are plotted alongside the curve fit to the salamander experimental data (green trace; see figure 4). Error bars indicate SEM. ** means P < 0.01, and * means P < 0.05.

Patient testing was performed with the Argus II’s maximum stimulus frequency (120 Hz) in order to match the salamander calcium imaging frequency (167 Hz) as best as possible. It should be noted, however, that Argus II stimulation is typically performed at 20 Hz [4, 5]. To determine whether the effects of interphase gap might be relevant at lower frequencies, we reran the salamander computer simulation at 20 Hz. For the IPG durations that were unaffected by anodic block (0.12–1.38 ms), the model’s predictions at 20 Hz differed by less than 4% of its predictions at 120 Hz.

4. Discussion

Our animal experiments, computational modeling, and human testing consistently demonstrated that introducing an interphase gap of appropriate duration within a biphasic stimulus protocol is effective in reducing retinal stimulation thresholds. In most cases, the effect of IPG duration on threshold could be described with a decaying exponential function. A similar observation was made in a study of cochlear implant users, in which the authors reported a negative exponential relationship between IPG length and the current needed to maintain constant loudness [13]. The asymptote of the exponential represents the point where the efficiency of pulses with long gaps approaches that of monophasic pulses [9, 12, 13]. This efficiency likely depends on the time at which the anodic (trailing) phase of the stimulus pulse occurs with respect to the rising phase of the action potential. At a certain point during the rising phase, positive feedback from voltage-gated Na+ channels causes the action potential to become self-sustaining. If the anodic phase occurs after this happens, the cell will fire, and its threshold will be similar to that of monophasic stimulation.

Our modeling studies suggest that the effects of interphase gap depend on both stimulus frequency and IPG duration. We observed that the combination of high-frequency stimulation and long interphase gaps produced a blocking effect that caused thresholds to increase. A similar finding has been reported in cochlear implant users [12]. There is clearly a tradeoff that must be made between stimulus frequency, pulse width, and IPG duration. Once IPG duration exceeds 0.5×stimulus period pulse width, stimulation effectively becomes anodic-first.

Though we investigated only a single pulse width (0.46 ms/phase), it is likely that pulse width also plays a role in determining how thresholds are affected by IPG. Indeed, other studies have found the effects of IPG to vary with pulse duration [9, 10, 13, 28]. Because threshold current generally decreases as pulses become longer [24, 29–31], it has been suggested that for a given stimulus duration, a longer pulse with no gap might be more effective than a shorter pulse containing a gap [28]. While this may be true in terms of reducing current, charge per phase is known to increase with pulse duration [24, 29–31]. Because electrochemical safety limits are defined in terms of charge (rather than current alone), it is likely that shorter pulses containing IPGs will provide more clinical benefit than longer, gapless pulses.

The effects of interphase gap were less pronounced in the human studies than in the salamander experiments and computational models. The most dramatic effects of IPG were predicted by the cat model. This agrees with another modeling study, in which IPG was found to affect cochlear thresholds in cats more dramatically than in humans [12]. Besides species differences, there are other possibilities for why we observed a larger effect on animal thresholds than on human thresholds. Human testing was performed on a small sample size. Intersubject differences include the amount of retinal degeneration, the position of the electrode relative to the fovea, and the distance between the electrode and retina. Each of these factors has been shown to affect perceptual threshold [4, 5, 32, 33]. Furthermore, the adaptation phenomenon we observed (see section 2.3) is time dependent; cessation of stimulation leads to gradual recovery from adaptation. The nature of human testing does not allow for precise control over the timing of threshold measurements. For example, subjects take different lengths of time to respond to stimuli. These variables introduce a large amount of noise into the perceptual threshold measurements.

Reducing thresholds would have several important implications for retinal prostheses. Clinical testing has shown that phosphenes tend to get larger and brighter as stimulus amplitude increases [14, 15, 33, 34]. Dynamic range of phosphene size and brightness is therefore defined as the difference between an electrode’s safety limit and its threshold current. Lowering threshold current would cause dynamic range to increase accordingly. It would also reduce the overall power consumption of the prosthesis, since less current would be required to elicit responses. Finally, it would allow some electrodes to elicit phosphenes that were previously unable to do so due to electrochemical safety limit restrictions. The benefits for individual patients would vary depending on their thresholds. For example, one patient in our study has 9 electrodes with thresholds ranging from the chronic safety limit to 15% above the limit. Stimulating with IPGs in this patient would be of great benefit. In other patients, use of IPGs would be less advantageous. For example, another patient in our study has only 2 electrodes with thresholds that fall within 15% of the chronic safety limit.

Our results suggest an optimal IPG duration of 0.5–1 ms for the pulse width used in this study (0.46 ms/phase). Interphase gap lengths up to 1 ms have already been used in early feasibility studies of retinal stimulation, with no evidence of negative effects [14–16]. In the future, more human testing may be needed to determine the optimal IPG length for other pulse durations and stimulus frequencies. Additional safety studies may be needed for IPGs greater than 1 ms. Key advantages of our approach are its simplicity and the fact that IPGs can be implemented without making changes to existing hardware or software.

Table 2.

Best-fit parameter values for decaying exponentials (see equation 4).

| τ (ms) | a (%) | b (%) | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salamander | 0.32 | 23.8 | −25.2 | 0.991 |

| Salamander Model | 0.28 | 31.9 | −32.1 | 0.999 |

| Cat Model | 0.52 | 59.3 | −59.3 | 0.999 |

| Human | 0.10 | 13.8 | −13.0 | 0.895 |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gislin Dagnelie and Mike Barry for performing some of the human subject testing, as well as Jessy Dorn and Maura Arsiero for their helpful advice. This work was supported in part by Second Sight Medical Products, Inc., the National Science Foundation (Grant #EEC-0310723 to JDW), the National Eye Institute (Grant #EY03040 to JDW and #1R01EY022931 to JDW/RHC), the Beckman Initiative for Macular Research (Grant #157370747 to RHC), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant #GM85791 to RHC), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant #DK091445 to RHC). Ashish Ahuja, Punita Christopher, Jianing Wei, Varalakshmi Wuyyuru, Uday Patel, and Robert Greenberg are/were employees of Second Sight Medical Products, Inc. Mark Humayun has a financial interest in and is a consultant for Second Sight Medical Products, Inc.

References

- 1.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahuja AK, Dorn JD, Caspi A, McMahon MJ, Dagnelie G, Dacruz L, Stanga P, Humayun MS, Greenberg RJ. Blind subjects implanted with the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis are able to improve performance in a spatial-motor task. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2011;95:539–543. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.179622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou DD, Greenberg RJ. In: Implantable Neural Prostheses. Zhou D, Greenbaum E, editors. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahuja AK, Behrend MR. The Argus II™ retinal prosthesis: Factors affecting patient selection for implantation. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2013:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja AK, Yeoh J, Dorn JD, Caspi A, Wuyyuru V, McMahon MJ, Humayun MS, Greenberg RJ, DaCruz L, Group AIS. Factors affecting perceptual threshold in Argus II retinal prosthesis subjects. Translational Vision Science and Technology. 2013;2:1–15. doi: 10.1167/tvst.2.4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humayun MS, Dorn JD, da Cruz L, Dagnelie G, Sahel JA, Stanga PE, Cideciyan AV, Duncan JL, Eliott D, Filley E. Interim results from the international trial of Second Sight's visual prosthesis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:779–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basinger BC, Rowley AP, Chen K, Humayun MS, Weiland JD. Finite element modeling of retinal prosthesis mechanics. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2009;6:055006. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/055006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prado-Guitierrez P, Fewster LM, Heasman JM, McKay CM, Shepherd RK. Effect of interphase gap and pulse duration on electrically evoked potentials is correlated with auditory nerve survival. Hearing Research. 2006;215:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepherd RK, Javel E. Electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve: II. Effect of stimulus waveshape on single fibre response properties. Hearing research. 1999;130:171–188. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman PH, Mortimer JT. The effect of stimulus parameters on the recruitment characteristics of direct nerve stimulation. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1983;30:407–414. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1983.325041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Honert C, Mortimer JT. The response of the myelinated nerve fiber to short duration biphasic stimulating currents. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 1979;7:117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02363130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlyon RP, van Wieringen A, Deeks JM, Long CJ, Lyzenga J, Wouters J. Effect of inter-phase gap on the sensitivity of cochlear implant users to electrical stimulation. Hearing Research. 2005;205:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKay CM, Henshall KR. The perceptual effects of interphase gap duration in cochlear implant stimulation. Hearing Research. 2003;181:94–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Balthasar C, Patel S, Roy A, Freda R, Greenwald S, Horsager A, Mahadevappa M, Yanai D, McMahon MJ, Humayun MS. Factors affecting perceptual thresholds in epiretinal prostheses. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2008;49:2303–2314. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwald SH, Horsager A, Humayun MS, Greenberg RJ, McMahon MJ, Fine I. Brightness as a function of current amplitude in human retinal electrical stimulation. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2009;50:5017–5025. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahadevappa M, Weiland JD, Yanai D, Fine I, Greenberg RJ, Humayun MS. Perceptual thresholds and electrode impedance in three retinal prosthesis subjects. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2005;13:201–206. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.848687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behrend MR, Ahuja AK, Humayun MS, Weiland JD, Chow RH. Selective labeling of retinal ganglion cells with calcium indicators by retrograde loading. in vitro Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2009;179:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gholmieh G, Soussou W, Han M, Ahuja A, Hsiao MC, Song D, Tanguay AR, Jr, Berger TW. Custom-designed high-density conformal planar multielectrode arrays for brain slice electrophysiology. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2006;152:116–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weitz AC, Behrend MR, Lee NS, Klein RL, Chiodo VA, Hauswirth WW, Humayun MS, Weiland JD, Chow RH. Imaging the response of the retina to electrical stimulation with genetically encoded calcium indicators. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2013;109:1979–1988. doi: 10.1152/jn.00852.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez Fornos A, Sommerhalder J, da Cruz L, Sahel JA, Mohand-Said S, Hafezi F, Pelizzone M. Temporal properties of visual perception on electrical stimulation of the retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53:2720–2731. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fohlmeister JF, Miller RF. Impulse encoding mechanisms of ganglion cells in the tiger salamander retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:1935–1947. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fohlmeister JF, Coleman PA, Miller RF. Modeling the repetitive firing of retinal ganglion cells. Brain Research. 1990;510:343–345. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91388-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benison G, Keizer J, Chalupa LM, Robinson DW. Modeling temporal behavior of postnatal cat retinal ganglion cells. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2001;210:187–199. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekirnjak C, Hottowy P, Sher A, Dabrowski W, Litke A, Chichilnisky E. Electrical stimulation of mammalian retinal ganglion cells with multielectrode arrays. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95:3311–3327. doi: 10.1152/jn.01168.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai D, Morley JW, Suaning GJ, Lovell NH. Frequency-dependent reduction of voltage-gated sodium current modulates retinal ganglion cell response rate to electrical stimulation. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2011;8:066007. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/6/066007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranck JB. Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Research. 1975;98:417–440. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merrill DR, Bikson M, Jefferys JGR. Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of efficacious and safe protocols. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2005;141:171–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.John SE, Shivdasani MN, Williams CE, Morley JW, Shepherd RK, Rathbone GD, Fallon JB. Suprachoroidal electrical stimulation: effects of stimulus pulse parameters on visual cortical responses. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2013;10:056011. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/5/056011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen RJ, Ziv OR, Rizzo JF. Thresholds for activation of rabbit retinal ganglion cells with relatively large, extracellular microelectrodes. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2005;46:1486–1496. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan LLH, Lee EJ, Humayun MS, Weiland JD. Both electrical stimulation thresholds and SMI-32-immunoreactive retinal ganglion cell density correlate with age in S334ter line 3 rat retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:2687–2697. doi: 10.1152/jn.00619.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahuja AK, Behrend MR, Kuroda M, Humayun MS, Weiland JD. An in vitro model of a retinal prosthesis. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2008;55:1744–1753. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2008.919126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humayun MS, De Juan E, Jr, Weiland JD, Dagnelie G, Katona S, Greenberg R, Suzuki S. Pattern electrical stimulation of the human retina. Vision Research. 1999;39:2569–2576. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humayun MS, Weiland JD, Fujii GY, Greenberg R, Williamson R, Little J, Mech B, Cimmarusti V, Van Boemel G, Dagnelie G. Visual perception in a blind subject with a chronic microelectronic retinal prosthesis. Vision Research. 2003;43:2573–2581. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanduri D, Fine I, Horsager A, Boynton GM, Humayun MS, Greenberg RJ, Weiland JD. Frequency and amplitude modulation have different effects on the percepts elicited by retinal stimulation. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2012;53:205–214. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]