Abstract

We utilize a recently developed microfluidic device, the Optimized Shape Cross-slot Extensional Rheometer (OSCER), to study the elongational flow behavior and rheological properties of hyaluronic acid (HA) solutions representative of the synovial fluid (SF) found in the knee joint. The OSCER geometry is a stagnation point device that imposes a planar extensional flow with a homogenous extension rate over a significant length of the inlet and outlet channel axes. Due to the compressive nature of the flow generated along the inlet channels, and the planar elongational flow along the outlet channels, the flow field in the OSCER device can also be considered as representative of the flow field that arises between compressing articular cartilage layers of the knee joints during running or jumping movements. Full-field birefringence microscopy measurements demonstrate a high degree of localized macromolecular orientation along streamlines passing close to the stagnation point of the OSCER device, while micro-particle image velocimetry is used to quantify the flow kinematics. The stress-optical rule is used to assess the local extensional viscosity in the elongating fluid elements as a function of the measured deformation rate. The large limiting values of the dimensionless Trouton ratio, Tr ∼ O(50), demonstrate that these fluids are highly extensional-thickening, providing a clear mechanism for the load-dampening properties of SF. The results also indicate the potential for utilizing the OSCER in screening of physiological SF samples, which will lead to improved understanding of, and therapies for, disease progression in arthritis sufferers.

INTRODUCTION

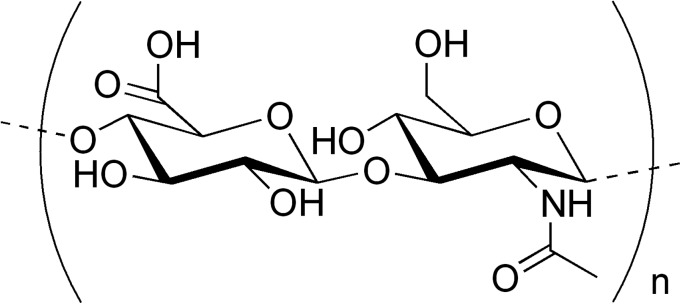

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring linear polysaccharide composed of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine disaccharide units linked by alternating β 1→3 and β 1→4 glycosidic bonds (see Fig. 1).1, 2

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the hyaluronic acid (HA) molecule.

Hyaluronic acid is found abundantly in many biological systems and occurs in particularly high concentrations in the vitreous humour of the eyes, umbilical cord, cockerel comb, and the synovial fluid (SF) of the joints.3 In healthy human synovial fluid, a broad range of values for the concentration of HA has been measured, ranging generally between around 0.05 and 0.4 wt. %, with 0.3 wt. % being typical.4, 5, 6 The molecular weight of HA in healthy SF can be extremely high and has been reported as reaching more than 7 MDa.7 The high concentration and molecular weight of the HA in SF confer strong viscoelastic properties to the fluid.8, 9 Synovial fluid is highly viscous (on the order of 10's to 100's of Pa s) and is strongly shear thinning;10, 11 a property which contributes to the highly effective lubrication of joints undergoing flexion. Synovial fluid is also highly elastic and it has been suggested that this may be the key to the shock-absorbing properties of SF that protects joints from sudden high-load impacts.12, 13

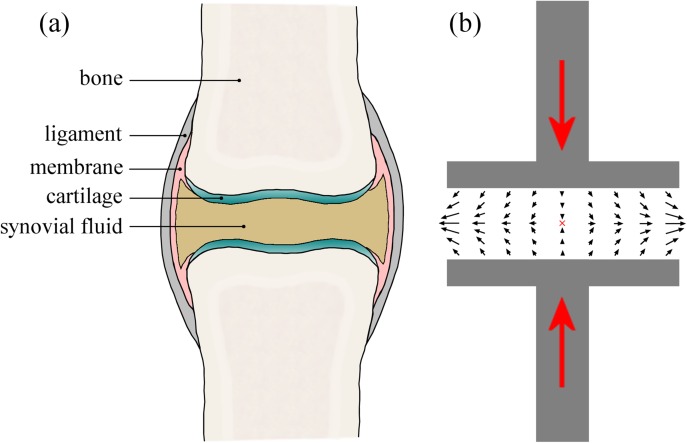

Compression of the synovial fluid in the joint cavities (e.g., between the femur and tibia in the knee, when running or landing after a jump) can be considered (in a simplified sense) essentially as a squeeze flow between two compressing disks or plates (see Fig. 2). In general, with a no-slip boundary condition at the plates, squeezing flows generate a complex time-varying and inhomogeneous flow field composed of strong shear near the surfaces of the plates and a biaxial extensional flow with a stagnation point at the mid-plane between the plates.14, 15 At the stagnation point, the fluid velocity is zero, so the residence time of material elements in the flow can be (in principle) infinite. Under such circumstances, flexible macromolecules are expected to unravel and stretch to a considerable fraction of their contour length provided the extension rate () exceeds the reciprocal of the longest macromolecular relaxation time (). This condition defines a critical value for the dimensionless flow strength or Weissenberg number, , above which macromolecules will stretch.16 This behavior has been demonstrated experimentally in many systems including direct observations of chain unraveling in fluorescently labeled DNA17, 18 and measurements of flow-induced birefringence in synthetic and biological polymer solutions.19, 20 Simulations of squeezing flows using a Finitely Extensible Non-linear Elastic (FENE) dumbbell-type model predict significant macromolecular stretching between the compressing plates for “fast squeezing”; i.e., when the timescale for the squeezing is much less than the relaxation time of the dumbbell or macromolecule.21

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic drawing of a synovial joint highlighting the important anatomic features. (b) Simplified picture of the squeeze flow in a synovial joint undergoing a compressive deformation (such as occurs in the knees during locomotion). The black arrows indicate the flow of the synovial fluid being squeezed outwards orthogonal to the compression axis, resulting in a biaxial extensional flow at the mid-plane between joint surfaces and a stagnation point at the center of symmetry (marked by the red “x”).

If perfect slip is allowed at the solid surfaces of the plates, the squeezing flow generates a homogeneous biaxial extensional flow field with no contribution from shear.15 Slip can be introduced into experimental squeeze flow apparatus through the introduction of thin layers of an immiscible low-viscosity lubricant at the plates, such that (ideally) shearing deformation is confined within the lubricating layer while the bulk fluid contained between the plates undergoes an homogeneous biaxial extension. Such lubricated squeezing devices have been demonstrated as effective biaxial extensional rheometers for relatively high-viscosity fluid samples such as polymer melts.22, 23

For the flow of shear-thinning fluids in squeeze flows, shear localization at the plate surfaces has a similar effect to partial slip at the surfaces.24 Effectively the fluid self-lubricates, resulting in a more plug-like flow in the bulk and an increased dominance of extensional effects over shearing contributions to the flow in the region of the mid-plane between the plates. Our results, based on the analysis of a power-law fluid in squeeze flow show that this self-lubricating effect remains significant even as the ratio of plate radius, R, to gap width, h, is increased to physiologically relevant values of .24

We note that in a real joint the bounding surfaces (i.e., the cartilage) are in fact charged, porous and compressible25, 26 and several mechanisms of joint lubrication have been suggested based on these physical properties of cartilage and their interaction with the synovial fluid. These include squeeze-film lubrication,25 weeping lubrication,27, 28, 29 boundary lubrication mediated by surface adsorbed lubricin proteins,30 and electrostatic binding of an HA network to the cartilage.26 While our simple picture of the compressing joint (as illustrated in Fig. 2) does not incorporate any of these additional complexities, we believe the basic squeeze flow description nevertheless captures many of the characteristics of the mixed extensional and shearing kinematics. Lubrication analysis of squeeze flow using a power-law constitutive model to represent the shear-thinning SF, clearly shows that for typical values of the geometric aspect ratio and shear-thinning exponent the flow field contains a significant region of extension-dominated flow.24 Based on this simplified scenario, we argue that in joints undergoing compressive deformations, shear-thinning of the synovial fluid at small gaps actually augments the importance of the extensional flow field between the two approaching cartilage surfaces.

Due to the very small gaps (∼O(100 μm)) between the articular cartilage layers and the short time scales involved in sudden joint impacts, only small deformations are required to generate high values of the extensional strain rate , which is estimated to range between 1 and 1000 in the knee.31 On the other hand, the high molecular weight of HA and the high viscosity of synovial fluid means the relaxation time, λ, of the HA in SF can be very long .11 Hence, it is highly likely that biologically relevant deformation rates generated within joints can result in high Weissenberg numbers for the HA macromolecules contained in the synovial fluid, and therefore induce significant stretching of the HA.12, 13 The stretching of macromolecules in solution can result in orders of magnitude increases in elastic stresses and the corresponding measure of the transient extensional viscosity.32, 33, 34 This provides a possible mechanism for energy dissipation during shock loading and the prevention of contact between cartilage layers in compressing joints.13

In patients with osteo- and rheumatoid arthritis, the properties of synovial fluid become degraded, with both the concentration and molecular weight of the HA being significantly altered4, 6, 7, 35, 36, 37 and the viscoelasticity significantly reduced. Monitoring the concentration and molecular weight of HA in SF (or alternatively the co-related viscoelastic properties of SF) therefore has potential as a marker for diagnosis of such joint diseases.35 An important application of commercially produced HA (normally isolated from cockerel combs or produced by bacterial fermentation) is in viscosupplementation of arthritic joints in order to enhance the properties of the diseased and degraded SF.3, 38, 39 A full characterization and understanding of the rheological properties of HA in solution is therefore vital for the optimization of the fluids used for this form of therapy. While such rheological studies are numerous for simple shearing flows that are relevant to joint flexion,11, 40, 41, 42, 43 detailed studies of extensional flows of HA solutions that could be relevant to SF function during joint compression remain scarce.11, 12, 13, 44

Backus et al.13 used an opposed-jets device, in “blowing mode,” in order to apply a biaxial extensional flow to solutions of two different high molecular weight HA samples (one linear and one cross-linked) used in viscosupplementation therapy. The fluids displayed a disk of birefringent material situated between the blowing jets, clearly demonstrating the extension of HA molecules in the flow field. Fluids were also tested in a custom-made compression cell, and showed a significant non-linear increase in the normal force response as the compression rate was increased. A cross-slot device was used to obtain a measure of the extensional viscosities of the test fluids, showing an increase with increasing deformation rates up to ˙ε 啈 40s⁻¹, followed by a reduction in extensional viscosity at higher rates. The reduction in extensional viscosity was attributed to the likely modification of the flow field by the stretching molecules and the consequent loss of the purely extensional flow field in the cross-slot device. The authors did not confirm this hypothesis directly but noted that full visualization of the flow field would have been a highly desirable complementary experiment.

In a recent study, Bingöl et al.11 performed comprehensive experiments on HA solutions in a physiological phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using both steady shear in a cone-and-plate rheometer and uniaxial extensional flow in a capillary thinning (CaBER) device. Hyaluronic acid solutions of two molecular weights (1.7 and 4.6 MDa) and a range of concentrations spanning were tested, along with “model” synovial fluid systems consisting of HA mixtures with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and γ-globulin. It has been suggested that complexes formed between HA and the proteins present in SF could play an important role in influencing SF rheological properties.45, 46 However, Bingöl et al.11 found no significant differences between the shear and extensional rheological properties of HA solutions with and without the proteins present, and concluded that it is the HA alone that is predominantly responsible for the functional properties of SF. In addition to HA solutions, Bingöl et al.11 also examined samples of real human SF in shear and extensional flow. They found that a 4.6 MDa HA at a concentration of c = 0.3 wt. % in PBS had shear and extensional rheological properties that compared well with the physiological SF samples.

A potential limitation of the work of Bingöl et al.11 is the use of a capillary thinning rheometer to study the extensional properties of HA solutions. In the CaBER device it is not possible to impose a controlled deformation rate to a fluid sample; the fluid simply drains, necks down, and eventually breaks up according to its own timescale, determined by a balance between viscous, capillary and elastic stresses.47 Also, since the CaBER is a free-surface instrument, hydrophobic molecules can be drawn to the air-liquid interface in the device, modifying the interfacial rheology and potentially affecting measurements by stabilizing the eventual breakup of the fluid filament.48, 49

Recently, we presented a novel microfluidic device for performing extensional rheometry of polymer solutions.50, 51 The Optimized Shape Cross-slot Extensional Rheometer (or OSCER) is similar to a cross-slot device, but has a shape that has been numerically optimized in order to generate a large region of homogenous planar extensional flow.50, 51 This device allows fluid extensional rheological properties to be measured as a function of the flow strength in a clean and enclosed environment, with no additional complicating effects resulting from the presence of a free surface and while using small volumes of fluid (O(10 ml)). In our previous experimental work,51 we demonstrated the use of the OSCER device for performing extensional rheometry with model dilute and non-shear-thinning solutions of flexible high molecular weight synthetic polymers, specifically poly(ethylene oxide) (or PEO). In the present work, we examine more complex viscoelastic fluids consisting of semi-dilute, shear-thinning solutions of semi-flexible HA macromolecules and also of HA/protein mixtures similar to those studied by Bingöl et al.11 The OSCER device enables us to determine fluid relaxation times and planar extensional viscosity behavior as a function of the deformation rate, which is not possible in the CaBER device employed by Bingöl et al.11 Our aim is to characterize the extensional properties of HA in solution and to assess whether or not the stretching of HA in synovial fluid can play a significant role in joint protection. This type of study may lead to improved formulation of prosthetic fluids with properties better matched to real SF. If we can demonstrate a direct connection between HA concentration and molecular weight and the extensional flow behavior of a given fluid, then our methods may also offer a technique for tracking changes in the synovial fluid HA characteristics during the progression of joint disease and thus potentially to a novel disease diagnostic technique. The remainder of the article is organized as follows: in Sec. 2, we present details of our test fluids and their characterization using standard cone-and-plate rheometric methods as well as high shear rate microfluidic rheometry. In Sec. 3, we describe our microfluidic extensional flow device and give details of the experimental techniques used to determine fluid relaxation times and extensional viscosities of the HA solutions. In Sec. 4, we present our results and in Sec. 5 we summarize our main conclusions.

TEST FLUIDS AND THEIR RHEOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION

The high molecular weight (MW = 1.6 MDa, as specified by the supplier) HA sample used in this study was obtained from Sigma Aldrich and was produced by fermentation of Streptococcus equi. For convenience we refer to it as HA1.6 in the remainder of the article. HA solutions were prepared at concentrations of 0.1 wt. % and 0.3 wt. % in a physiological phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 7.4, obtained from Sigma Aldrich). We also prepared a model synovial fluid formed from a solution of 0.3 wt. % HA combined with 1.1 wt. % BSA, and 0.7 wt. % γ-globulin.46 Light scattering experiments indicate an overlap concentration of c* for this HA molecule in PBS solution, suggesting that our solutions are in the semi-dilute regime.42, 52

All of the test solutions were prepared by weighing the HA and protein powders into a glass container and adding the appropriate volume of PBS solution. In order to avoid mechanical degradation of the HA during dissolution, magnetic stirring was avoided; instead occasional gentle manual agitation was applied to the containing vessel until the solution appeared completely transparent and homogenous. This typically took around 36 h. Following complete dissolution of the sample in the PBS, the fluid was tested without delay (i.e., within the subsequent 12 h) to determine the rheological and extensional flow properties.

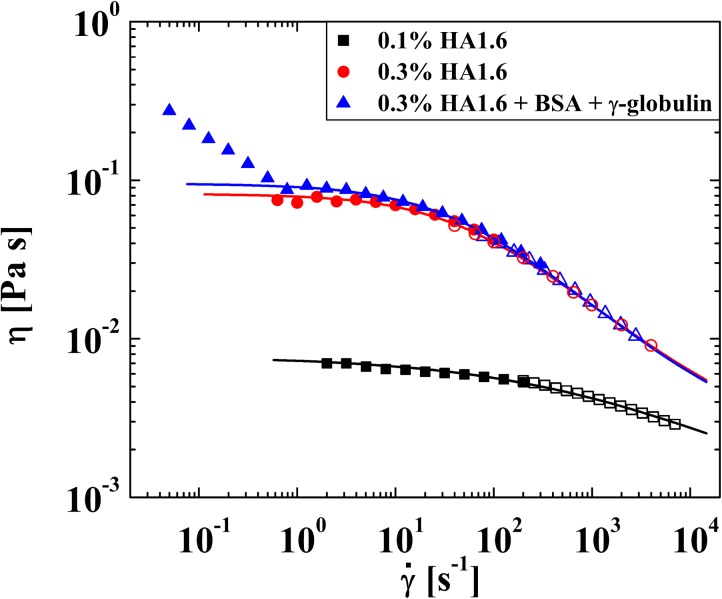

Test solutions were characterized by steady shear experiments in an AR-G2 stress-controlled rheometer with a 40 mm diameter 2° cone-and-plate fixture. To access higher shear rates a microfluidic shear rheometer was used (m-VROC, Rheosense Inc, CA).53 The results of the experiments are presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Steady shear viscosity of HA/PBS solutions measured using an AR-G2 stress-controlled cone-and-plate rheometer (closed symbols) and an m-VROC microfluidic rheometer (open symbols). The viscosity is well-described by a Carreau-Yasuda model (solid lines), except for the fluid containing BSA and γ-globulin at low shear rates.

In the absence of added protein, the steady shear rheology presented in Fig. 3 is highly comparable with that of previous authors using microbial HA solutions of comparable molecular weight and concentration under equivalent solvent conditions.11, 41, 42 For example, Krause et al.41 report that a solution with 0.3 wt. % of a hyaluronic acid of MW = 1.5 MDa has a zero-shear-rate viscosity of , which commences to shear thin at a characteristic shear rate of and to reach a viscosity of at a shear rate of The fluids used in the present work also display a zero-shear-rate viscosity plateau and are shear-thinning. Increasing the HA concentration from 0.1 wt. % to 0.3 wt. % results in a significant increase in and in a more pronounced shear-thinning behavior. At 0.3 wt. %, the viscosity drops by almost an order of magnitude over two decades in shear rate. Addition of 1.1 wt. % BSA and 0.7 wt. % γ-globulin to the 0.3 wt. % HA solution, appears to have little effect on the fluid rheology except at low shear rates, where an additional region of strong shear-thinning is observed. Such behavior was also reported by Oates et al.45 using a concentric cylinder geometry and was attributed to complexation between the HA and protein resulting in the formation of a weak gel. However, Bingöl et al.11 observed no such phenomenon in a 60 mm diameter 1° cone-and-plate geometry. The fact that the observation of this phenomenon depends on the flow geometry employed suggests that it may be due to an interfacial, as opposed to a bulk, property of the fluid49, 54 and we intend to investigate this possibility further in future work. In general, the fluid steady shear viscosity is well described by the Carreau-Yasuda model55

| (1) |

where is the infinite-shear-rate viscosity, is the zero-shear-rate viscosity, is the characteristic shear rate for the onset of shear-thinning, n is the “power-law exponent,” and a is a dimensionless fitting parameter that influences the sharpness of the transition from a constant shear viscosity at low shear rates to the power-law region. The values of these parameters determined for all the test fluids are provided in Table TABLE I..

TABLE I.

Parameters used to fit the Carreau-Yasuda model to the steady shear rheology data.

| HA1.6 concentration (wt. %) | (Pa s) | (Pa s) | () | n | a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.0073 | 0.001 | 200 | 0.68 | 0.60 |

| 0.3 | 0.082 | 0.002 | 50 | 0.45 | 0.75 |

| 0.3 + BSA + γ-globulin | 0.097 | 0.0021 | 45 | 0.42 | 0.72 |

The power-law exponents (n) shown in Table TABLE I. indicate the highly shear-thinning nature of the HA-based test fluids at shear rates . However, it should be noted that the steady shear rheology of fluids, with higher HA concentrations or MW, and also of real synovial fluid, can be significantly more shear-thinning than this, with (and sometimes even less).11

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Extensional flow apparatus

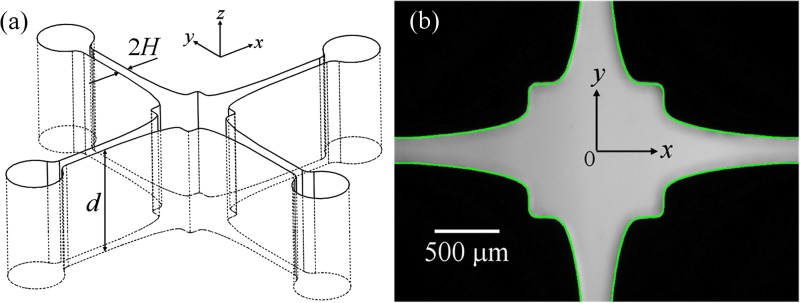

We refer to the microfluidic device used to generate the extensional flow field as the Optimized Shape Cross-slot Extensional Rheometer (OSCER). The OSCER geometry operates on principles similar to traditional cross-slots (i.e., with opposed inlets and outlets to generate a free stagnation point)17, 20 but has an optimized shape that achieves a homogeneous strain rate along a significant portion of the inlet and outlet channel axes.50, 51 A 3D drawing and a photograph of the actual flow geometry are provided in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

(a) 3D view of the OSCER geometry showing the upstream and downstream characteristic channel dimension H and the uniform depth d. (b) Light micrograph of the actual OSCER geometry. The inflow is along the y- and the outflow along the x-direction. At the center of the geometry there is a stagnation point, here marked as the origin of coordinates. The superimposed green line represents the prescribed profile determined from numerical optimization.

The OSCER geometry is precision micro-machined in stainless steel using the technique of wire electrical discharge machining (EDM). It has initially parallel channels far upstream and far downstream of the stagnation point, with a characteristic dimension of H = 100 μm, and a uniform depth of d = 2100 μm, providing a high aspect ratio of α = 10.5 and hence a good approximation to a 2D flow. The geometry is optimized over the central 3 mm (30 H) section of the device, i.e., ± 15 H either side of the stagnation point in both the x- and y directions. The extensional deformation rate (or strain rate, ) has been shown to be nominally constant over this optimized region in both Newtonian fluids and viscoelastic polymer solutions.51

Experiments are conducted at controlled total volume flow rates, Q, using a Harvard PHD-Ultra syringe pump to drive the flow from a single syringe into both opposing inlets of the OSCER device. We define the superficial flow velocity, U, as the average flow velocity in the upstream and downstream parallel sections of channel: U = Q/(4Hd). The homogenous strain rate, , on the flow axes depends on the imposed flow velocity and is measured experimentally using micro-particle image velocimetry (μ-PIV), see Sec. 3B.

We define the dimensionless flow strength or Weissenberg number as

| (2) |

where λ is the fluid relaxation time, which will be assessed from measurements of flow-induced birefringence in the extensional flow field (see Sec. 3C).

The Reynolds number is used to characterize inertial contributions to the flow and is defined as

| (3) |

where is the fluid density, is the hydraulic diameter and is the shear-rate dependent viscosity (see Fig. 3 and Table TABLE I.), evaluated at the characteristic shear rate where is the second invariant of the shear rate tensor . This is valid assuming an ideal planar extensional flow, , within the OSCER device.

Flow field in the OSCER device

Flow visualization

To obtain a qualitative impression of the flow field within the OSCER device, the fluid is seeded with 8 μm diameter fluorescent spheres (excitation:emission 520:580 nm, c = 0.02 wt. %). The flow geometry is placed on the imaging stage of a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S inverted microscope and is continuously illuminated with a mercury lamp at 532 nm using a filter cube. A 2× 0.06 NA objective lens is used to focus on the mid-plane of the flow geometry and streak images are captured using an MV Bluefox 640 × 480 pixel CCD camera set to a long exposure time of 0.25 s.

Micro-PIV

For quantitative measurements of the flow kinematics, micro-particle image velocimetry (μ-PIV) is performed on test fluid seeded with 1.1 μm diameter fluorescent spheres (excitation:emission 520:580 nm, c = 0.02 wt. %). A 4× 0.13 NA objective is used to focus on the mid-plane of the flow cell. The resulting measurement depth over which microparticles contribute to the determination of the velocity field is approximately 150 μm, or only 7% of the channel depth.56 The fluid is illuminated by a double-pulsed 532 nm Nd:YAG laser with pulse width δt = 5 ns. The fluorescent seed particles absorb the laser light and emit at a longer wavelength. The laser light is filtered out with a G-2A epifluorescent filter, so that only the light emitted by fluorescing particles is detected by a CCD array. A 1.4 megapixel, frame-straddling CCD camera (TSI Instruments, PIV-Cam) is used to capture image pairs with a time separation (10 μs < Δt < 320 μs, depending on the flow rate) chosen to achieve an average particle displacement of approximately four pixels, optimal for subsequent PIV analysis. Image pairs are captured at a rate of approximately four pairs per second. The standard cross-correlation PIV algorithm (TSI insight software), with interrogation areas of 32 × 32 pixels and Nyquist criterion, is used to analyze each image pair. Twenty image pairs are captured and ensemble-averaged in order to obtain full-field velocity maps in the vicinity of the stagnation point. tecplot 10 software (Amtec Eng. Inc.) is used to extract velocity profiles and hence deformation rates, , from the resulting vector fields.

Flow-induced birefringence measurement

The spatial distribution of flow-induced birefringence in the central region of the OSCER device is measured using an ABRIO birefringence imaging system (CRi Inc., MA). Briefly, the cross-slot flow cell is placed on the imaging stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S) and the mid-plane of the flow cell is brought into focus using a 4× 0.13 NA objective lens. Circularly polarized monochromatic light (wavelength 546 nm) is passed first through the sample, then through a liquid crystal compensator optic and finally onto a CCD array. The CCD camera records five individual frames with the liquid crystal compensator configured in a specific polarization state for each frame. Data processing algorithms described by Shribak and Oldenbourg57 combine the five individual frames into a single full-field map of retardation and orientation angle. The system can measure the retardation (R) to a nominal resolution of approximately 0.02 nm and has an excellent spatial resolution (projected pixel size approximately 2 μm with a 4× objective lens). Assuming 2D flow, the relationship between retardation and birefringence is given by

| (4) |

where d is the depth of the flow cell and is the birefringence.

The birefringence intensity measured along the stagnation point streamline of the OSCER device is used to determine the local extensional viscosity of the fluid () using the stress-optical rule (SOR). The SOR states that, for a range of microstructural deformations, the magnitude of the birefringence () is directly proportional to the principal stress difference in the fluid (), i.e.,

| (5) |

where the constant of proportionality, C, is called the stress-optical coefficient. For solutions of 1.5 MDa HA in PBS over a concentration range of , the stress-optical coefficient has been determined rheo-optically to be .42

The apparent extensional viscosity follows directly from:

| (6) |

We define the dimensionless Trouton ratio, Tr, as the ratio of extensional viscosity to shear viscosity, i.e.,

| (7) |

where the shear viscosity, η, is evaluated using the Carreau-Yasuda model fits to the steady shear rheology, evaluated at the characteristic shear rate, .

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

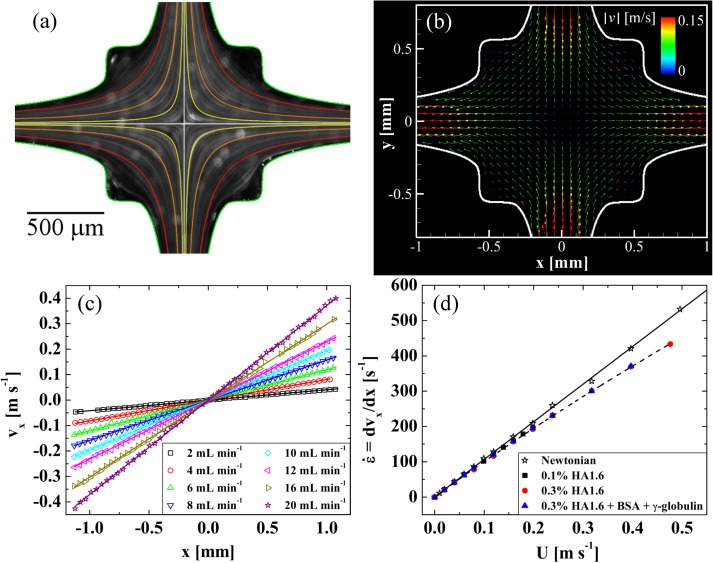

In Fig. 5, we present a detailed experimental analysis of the flow field within the OSCER device. In Fig. 5a, we show streak imaging performed with a Newtonian fluid consisting of 66 wt. % glycerol in water. The fluid viscosity is approximately 13 mPa s and the volume flow rate is Q = 0.5 , equivalent to U = 0.01 and . Superimposed in color on the streak image is a family of hyperbolic streamlines (defined by y = k/x, for a range of k values) expected for an ideal homogeneous extensional flow, and it is clear that in the central region of the device the experimental streamlines broadly follow these hyperbolae. Superimposed in white are the x and y axes of symmetry, which clearly bisect at the hyperbolic singularity (the stagnation point) at the center of the OSCER geometry.

Figure 5.

(a) Streak imaging showing the nature of the flow field in the OSCER with a Newtonian fluid at U = 0.01 , with superimposed colored hyperbolae for comparison. The superimposed white lines indicate the symmetry axes of the geometry, which coincide at the stagnation point. Flow enters through the top and bottom channels and exits through the left- and right-hand channels. (b) Experimental flow velocity vector field, measured using μ-PIV, for an analogue synovial fluid at U = 0.2 (Re = 2.8, Wi = 3.1). (c) Outflow velocity vx (x) measured along y = 0 for the analogue synovial fluid. At any given flow rate vx varies linearly with x and the slope of the straight line provides the elongation rate along the exit channel centerline. (d) Elongation rate as a function of superficial flow velocity for HA1.6 solutions in the OSCER, compared with the result for a Newtonian fluid.

In Fig. 5b, we show a velocity vector field measured using μ-PIV in a model synovial fluid consisting of 0.3 wt. % HA1.6 with 1.1 wt. % BSA and 0.7 wt. % γ-globulin. The superficial flow velocity is U = 0.2 (Re = 2.8, Wi = 3.1). Here, we can see quantitatively how the flow velocity approaches zero at the center of the OSCER device and how fluid elements are stretched continuously as they flow outwards along the x-direction. The flow field in the OSCER can be viewed as a planar analogue of the biaxial extensional flow resulting from the squeeze flow of shear-thinning fluids confined between two circular plates.24 Taking a line profile along the y = 0 axis of Fig. 5b, we can extract as a function of x, as shown in Fig. 5c for the model synovial fluid over a range of volume flow rates. It is clear that, at each volume flow rate, varies linearly with x providing a nominally constant velocity gradient along the x-axis. Such measurements have been made for the Newtonian fluid and all three HA1.6-based test solutions and the resulting strain rate, , as a function of bulk flow velocity, U, is shown in Fig. 5d. In the Newtonian fluid, the strain rate increases linearly with U as (with U in , as shown by the solid line). In the HA solutions at low flow rates the Newtonian trend is obeyed, however, at higher flow rates, a weak power-law dependency is observed and the strain rate drops slightly, but progressively, below the Newtonian expectation. Consequently, in the HA solutions, the extension rate is better described by the equation (shown by the dashed line). Similar behavior was reported by Haward et al.51 with dilute PEO solutions and was shown to be connected to the formation of a birefringent elastic strand localized along the outflowing axis. Such flow-induced structures act as internal stress boundary layers, causing perturbations to the local flow velocity field and modifying local velocity gradients.58 However, it is important and interesting to note that this flow perturbation apparently does not affect the spatial homogeneity of the deformation rate measured along the outflow (y = 0) axis, as is evident from the linear variation of shown in Fig. 5c.

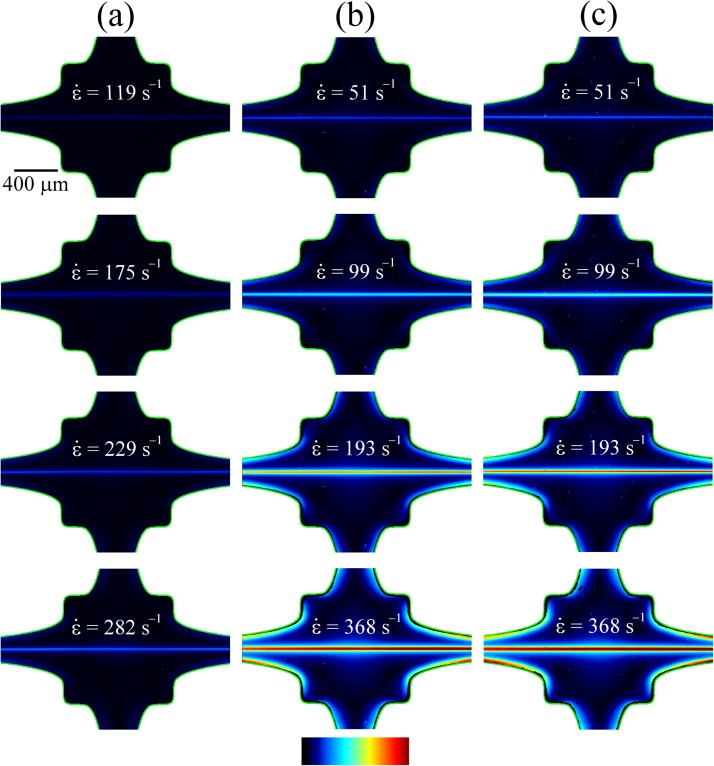

As was seen in previous work with aqueous PEO solutions,51 with the HA1.6 solutions we also observe the formation of a localized birefringent strand along the outflowing stagnation point streamline. The progressive development and strengthening of this strand with increasing values of the flow rate through the OSCER device is shown in Fig. 6. At the flow rates (or strain rates) at which the birefringence first becomes measurable, the birefringence microscopy images in Fig. 6 indicate that significant macromolecular stretching and orientation takes place only along streamlines that pass close to the stagnation point, where the residence times in the high velocity gradient are maximal. The intensity of the birefringence along the x-axis can be seen to be almost constant, which is a result of the homogenous strain rate along the x-axis and provides a clear visual demonstration of the strong extensional flow field generated in the OSCER device. The intensities of the birefringent strands shown in Fig. 6 increase as the imposed strain rate are incrementally increased. The fluids with the higher concentration of HA (Figs. 6b, 6c) are significantly more birefringent than the low concentration fluid (Fig. 6a), as expected. Additionally, for a given strain rate, we observe little qualitative difference between the behavior of the two 0.3 wt. % HA1.6 fluids with and without added protein.

Figure 6.

Flow induced birefringence measured over a range of extension rates in solutions of HA1.6: (a) 0.1 wt. %, (b) 0.3 wt. %, (c) 0.3 wt. % + BSA + γ-globulin. The color scale bar represents retardation in the range R = 0–10 nm.

In addition, as the flow rate is incremented, not only the extensional strain rate in the OSCER device but also the shear rate near the curved non-slip walls of the device is increased. Here, the flow field is not purely extensional in character, and shear stresses as well as the first normal stress difference contribute to the total principal stress difference in the fluid. As this occurs, the more concentrated HA solutions (Figs. 6b, 6c) display a clear increase in the birefringence (or equivalently the principal stress difference) along the walls of the flow geometry. However, it should be noted that the magnitude of the stress difference along the channel walls is never as great as that observed along the channel center-plane. Note that at higher flow rates the more dilute HA solution (Fig. 6a) also displays such stress boundary layers at the channel walls, however, in this case, the intensity of the birefringence is very low indeed and is difficult to observe.

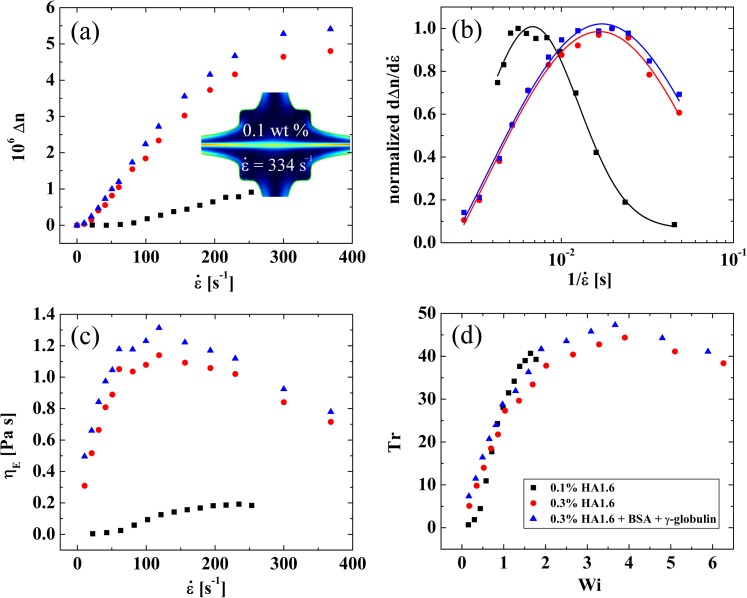

By measuring the birefringence on the x-axis (averaging along sections of strands close to the stagnation point), we obtain the birefringence, Δn, as a function of the strain rate for the three HA1.6 solutions, as shown in Fig. 7a. In the two 0.3 wt. % HA1.6 fluids, with and without added protein, we observe an initial increase in the birefringence at a strain rate of , up to similar plateau values of at strain rates of . In the 0.1 wt. % HA1.6 solution the initial increase in Δn occurs at a higher value of , and we are not able to reach a plateau value of birefringence due to the onset of an inertio-elastic instability that distorts the birefringent strand (as shown by the inset birefringence field image in Fig. 7a captured at ).

Figure 7.

(a) Measured birefringence () as a function of the strain rate () for HA1.6 solutions in the OSCER. In the 0.1 wt. % solution the experiment is curtailed at lower due to the onset of an inertio-elastic instability that distorts the birefringent strand (as illustrated by the inserted image for U = 0.36 m , Re = 29, Wi = 2.4). (b) Derivatives of the curves shown in part (a) (i.e., , normalized by their maximum values) plotted against . The data are fitted with log-normal distributions, the peak of which can be used as a measure of the fluid relaxation time (λ). (c) Extensional viscosity () as a function of , determined from birefringence measurements using the stress-optical rule. (d) Trouton ratio () as a function of the Weissenberg number ().

Since we broadly expect macromolecules to stretch when the characteristic Weissenberg number, , exceeds unity, i.e., ,16 it is apparent that we can obtain a characteristic macromolecular relaxation time (or Zimm coil→stretch characteristic time) from the birefringence data by measuring the rate of increase in the birefringence with strain rate and considering . However, this approach is made more complex due to the molecular weight distribution of the HA sample, which results in different molecular weight species within the sample stretching at different values of , hence the gradual increase of , with strain rate observed in Fig. 7a.59 In fact for dilute solutions of non-interacting macromolecules, the birefringence versus strain rate curve can be considered as a cumulative molecular weight distribution, though caution should be exercised in the present case since the fluids are semi-dilute and intermolecular interactions may be significant.

By differentiating the curves shown in Fig. 7a with respect to , and plotting the results as a function of , we obtain curves which are well described by log-normal distribution functions (see Fig. 7b). The variance of the log-normal distributions is indicative of the polydispersity in molecular weight of the HA sample and the peak of the distributions occurs at the critical strain rate at which the largest fraction of the HA in the solution begins to stretch. Therefore, we can take the reciprocal strain rate at the peak of the log-normal distribution function as a characteristic relaxation time for the HA1.6 molecule. In the 0.1 wt. % HA1.6 solution we find , while at the higher concentration of 0.3 wt. % HA1.6, we find . With the additional protein in the 0.3 wt. % HA1.6 solution, we find the relaxation time remains essentially unchanged (). These relaxation times are in excellent agreement with those reported by Bingöl et al.11 for similar HA solutions using a capillary breakup (CaBER) device. Bingöl et al.11 reported the relaxation time for HA solutions with added BSA and γ-globulin increased by approximately 20%; an effect that they attributed to the protein causing a reduction in the surface tension of the fluid. The fact that, in our interface-free microfluidic device, we observe a negligible change in relaxation time on addition of protein to the solution lends support to this hypothesis. The increase in relaxation time from approximately 7 to 17 ms between the 0.1 wt. % and 0.3 wt. % HA1.6 solutions is consistent with the increase in fluid viscosity and an expected increase in intermolecular interactions, since these fluids are in the semi-dilute regime.

Using the stress-optical rule to convert from birefringence to an extensional viscosity (Eqs. 5, 6), we obtain the extensional viscosity versus strain rate curves shown in Fig. 7c. In the 0.1 wt. % HA1.6 solution, the extensional viscosity increases at a strain rate of approximately 50 and rises to a plateau value of around 0.2 Pa s. In the more concentrated HA1.6 solutions, the extensional viscosity begins to increase even from the lowest applied strain rates and rises very rapidly to a maximum value of for , before gradually thinning with further increases in the strain rate. When the extensional viscosity is compared with the steady shear viscosity to obtain the dimensionless Trouton ratio (Eq. 7) as a function of Wi, we find that the data essentially collapse onto a single curve, as shown in Fig. 7d. The Trouton ratio reaches a maximum value of for a Weissenberg number of . This is of similar magnitude to the Trouton ratios that can be estimated from the extensional viscosity results reported by Bingöl et al.11 using similar fluids in a shear-free uniaxial extensional flow in a CaBER device. For example with a 0.22 wt. % solution of MW = 1.7 MDa HA in PBS, they report and , hence . With a 0.44 wt. % solution of the same HA in PBS, they report and , hence . Also in agreement with Bingöl et al.,11 in our microfluidic extensional rheometer, we find there is only a marginal difference in the extensional response of the fluids with and without added protein, which strongly indicates that it is the hyaluronic acid alone that confers functional viscoelastic properties to synovial fluid.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we have demonstrated the application of a recently developed numerically optimized microfluidic cross-slot (OSCER) device to test the extensional response of biologically-relevant hyaluronic acid solutions. Analogous formulations of fluids are used for viscosupplementation of the degraded synovial fluid in patients with joint disease, especially in the articular cavity of the knees. Our microfluidic device provides a good model of the flow field within the knee joint as it undergoes compressional and extensional deformations (e.g., during running and jumping activities), in which the synovial fluid is squeezed at high deformation rates (and thus at Wi ≫ 1). Our birefringence observations and measurements with semi-dilute HA solutions clearly demonstrate that these high molecular weight polysaccharides stretch significantly under such conditions of high flow strength, resulting in a significant increase in the extensional viscosity and in the corresponding dimensionless Trouton ratio. This is likely to represent an important functional aspect of synovial fluid, which allows it to resist compression under high loading rates at short time scales, thus preventing damaging contact from occurring between articular cartilage layers.

In future work, we intend to use the OSCER device to examine HA solutions over a range of molecular weight and concentration, allowing us to obtain the molecular weight dependency of the coil→stretch relaxation time and the concentration dependency of the birefringence. This will lead to the possibility of screening small samples of native synovial fluid in order to assess the molecular weight distribution and concentration of the HA, providing minimally invasive diagnostic techniques for joint diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.J.H., A.J., and G.H.M. gratefully acknowledge NASA Microgravity Fluid Sciences (Code UG) for support of this research under Grant No. NNX09AV99G. M.S.N.O. and M.A.A. acknowledge the financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, FEDER and COMPETE through projects PTDC/EME-MFE/114322/2009 and PTDC/EQU-FTT/118716/2010. M.S.N.O. also acknowledges GRPe—Glasgow Research Partnership in Engineering. This research was also supported by a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Programme.

Paper submitted as part of the 3rd European Conference on Microfluidics (Guest Editors: J. Brandner, S. Colin, G. L. Morini). The Conference was held in Heidelberg, Germany, December 3–5, 2012.

References

- Weissmann B. and Meyer K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76, 1753 (1954). 10.1021/ja01636a010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guss J. M., Hukins W. L., and Smith P. J. C., J. Mol. Biol. 95, 359 (1975). 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90196-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan G., Soltes L., Stern R., and Gemeiner P., Biotechnol. Lett. 29, 17 (2007). 10.1007/s10529-006-9219-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker B., McGuckin W. F., McKenzie B. F., and Slocumb C. H., Clin. Chem. 5, 465 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs E. A., Watson D., Duff I. F., and Roseman S., Arthritis Rheum. 10, 357 (1967). 10.1002/art.1780100407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollet A. J., J. Lab. Clin. Med. 48, 721 (1956). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl L. B., Dahl I. M., Engstrom-Laurent A., and Granath K., Ann. Rheum. Dis. 44, 817 (1985). 10.1136/ard.44.12.817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba R. S., Shuster S., Tucker P., and Stern R., Clin. Orthop. Relat. R. 363, 158 (1999). 10.1097/00003086-199906000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucco D., McKinley G. H., Scott R. D., and Spector M., J. Orthop. Res. 20, 1157 (2002). 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey A. J. and Davies D. V., J. Appl. Physiol. 25, 672 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingöl A. Ö., Lohmann D., Püschel K., and Kulicke W.-M., Biorheology 47, 205 (2010). 10.3233/BIR-2010-0572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Assaf S., Meadows J., Phillips G. O., and Williams P. A., Biorheology 33, 319 (1996). 10.1016/0006-355X(96)00025-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backus C., Carrington S. P., Fisher L. R., Odell J. A., and Rodrigues D. A., in Hyaluronan Volume 1: Chemical Biochemical and Biological Aspects, edited by Kennedy J. F., Phillips G. O., Williams P. A., and Hascall V. C. (Woodhead Publishing Ltd, Cambridge, 2002), pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Leider P. J. and Bird R. B., Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 13, 336 (1974). 10.1021/i160052a007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engmann J., Servais C., and Burbidge A. S., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 132, 1 (2005). 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2005.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Gennes P. G., J. Chem. Phys. 60, 5030 (1974). 10.1063/1.1681018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins T. T., Smith D. E., and Chu S., Science 276, 2016 (1997). 10.1126/science.276.5321.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. E. and Chu S., Science 281, 1335 (1998). 10.1126/science.281.5381.1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell J. A. and Carrington S. P., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 137, 110 (2006). 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2006.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haward S. J., Sharma V., and Odell J. A., Soft Matter 7, 9908 (2011). 10.1039/c1sm05493g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mochimaru Y., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 9, 157 (1987). 10.1016/0377-0257(87)87013-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatraei S., Macosko C. W., and Winter H. H., J. Rheol. 25, 433 (1981). 10.1122/1.549648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venerus D. C., Shiu T.-Y., Kashyap T., and Hosttetler J., J. Rheol. 54, 1083 (2010). 10.1122/1.3474599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4816708 for an analysis of the flow field and flow type for a power-law fluid undergoing squeeze flow between two parallel plates.

- Hou J. S., Mow V. C., Lai W. M., and Holmes M. H., J. Biomech. 25, 247 (1992). 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90024-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D. F., Fick G. M., and Baines W. D., J. Biomech. Eng. 132, 071002 (2010). 10.1115/1.4001422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen C. W., Nature 184, 1284 (1959). 10.1038/1841284a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P. R. and McCutchen C. W., Nature 184, 1285 (1959). 10.1038/1841285a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell K. C., Hodge W. A., Krebs D. E., and Mann R. W., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 14819 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0507117102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay G. D., Harris D. A., and Cha C. J., Glycoconj. J. 18, 807 (2001). 10.1023/A:1021159619373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurz J. and Ribitsch V., Biorheology 24, 385 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A. J., Odell J. A., and Keller A., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 30, 99 (1988). 10.1016/0377-0257(88)85018-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tirtaatmadja V. and Sridhar T., J. Rheol. 37, 1081 (1993). 10.1122/1.550372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie C. J. S., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 137, 1 (2006). 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2006.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Praest B. M., Greiling H., and Kock R., Clin. Chim. Acta. 266, 117 (1997). 10.1016/S0009-8981(97)00122-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. G. and Kling D. H., J. Clin. Invest. 35, 1419 (1956). 10.1172/JCI103399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E., Jacobs J. H., and Markham R. L., Clin. Sci. 14, 653 (1955). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone S., Palmeri D., and Berg R., J. Biomed. Mat. Res. 76A, 721 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.a.30623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K. D., Block J. A., Michalski J. P., Moreland L. W., Caldwell J. R., and Lavin P. T., Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 385, 130 (2001). 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouissac E., Milas M., and Rinaudo M., Macromolecules 26, 6945 (1993). 10.1021/ma00077a036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause W. E., Bellomo E. G., and Colby R. H., Biomacromolecules 2, 65 (2001). 10.1021/bm0055798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Lohmann D., and Kulicke W.-M., J. Rheol. 53, 799 (2009). 10.1122/1.3122985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fam H., Kontopoulou M., and Bryant J. T., Biorheology 46, 31 (2009). 10.3233/BIR-2009-0521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y. and Nishinari K., Biorheology 38, 379 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates K. M. N., Krause W. E., and Colby R. H., in Proceedings of the Materials Research Society Fall Meeting, Boston, MA, 26–29 November 2001 (Materials Research Society, Warrendale, 2002), pp. FF4.7.1–FF4.7.6.

- Oates K. M. N., Krause W. E., Jones R. L., and Colby R. H., J. R. Soc. Interface 3, 167 (2006). 10.1098/rsif.2005.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entov V. M. and Hinch E. J., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 72, 31 (1997). 10.1016/S0377-0257(97)00022-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regev O., Vandebril S., Zussman E., and Clasen C., Polymer 51, 2611 (2010). 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.03.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Jaishankar A., Wang Y.-C., and McKinley G. H., Soft Matter 7, 5150 (2011). 10.1039/c0sm01312a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alves M. A., in Proceedings of the XVth International Congress on Rheology, The Society of Rheology 80th Annual Meeting, Monterey, CA, 3–8 August 2008, edited by Co A., Leal L. G., Colby R. H., and Giacomin A. J. (Amer Inst Physics, Melville, 2008), pp. 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Haward S. J., Oliveira M. S. N., Alves M. A., and McKinley G. H., Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 128301 (2012). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.128301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendichi R., Šoltés L., and Schieroni A. G., Biomacromolecules 4, 1805 (2003). 10.1021/bm0342178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipe C. J., Majmudar T. S., and McKinley G. H., Rheol. Acta 47, 621 (2008). 10.1007/s00397-008-0268-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr H. R. and Warburton B., Biorheology 22, 133 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird R. B., Armstrong R. C., and Hassager O., Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Fluid Dynamics (Wiley, New York, 1987), Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhart C. D., Wereley S. T., and Gray M. H. B., Meas. Sci. Technol. 11, 809 (2000). 10.1088/0957-0233/11/6/326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shribak M. and Oldenbourg R., Appl. Opt. 42, 3009 (2003). 10.1364/AO.42.003009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlen O. G., Rallison J. M., and Chilcott M. D., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 34, 319 (1990). 10.1016/0377-0257(90)80027-W [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A. and Odell J. A., Colloid Polym. Sci. 263, 181 (1985). 10.1007/BF01415506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]