Abstract

Purpose

We have developed a reliable and valid clinical test of reaction time (RTclin) that is sensitive to the acute effects of concussion. If RTclin is to be used as a sideline concussion assessment tool then the acute effects of exercise on RTclin may need to be controlled for. The purpose of this study is therefore to determine the effect of exercise on RTclin.

Methods

A gender balanced group of 42 collegiate athletes were assigned to an exercise (n=28) and a control (n=14) group using 2:1 block randomization. The exercise group completed a graded 4-stage exercise protocol on a stationary bicycle (100W × 5min; 150W × 5min; 200W × 5min; sprint × 2min) while the control group was tested at identical time periods without exercising. Mean RTclin was calculated over 8 trials as the fall time of a vertically-suspended rigid shaft after its release by the examiner before being caught by the athlete; RTclin was measured at baseline and after each of the 4 stages.

Results

As both heart rate and rate of perceived exertion significantly increased over the 4 stages in the exercise group (p<.001), mean RTclin showed a significant overall decline during repeated test administration (p<.008). However, there were no significant group (exercise vs. control, p=0.822) or group-by-stage interaction (p=0.169) effects on RTclin as assessed by repeated measures analysis of variance.

Conclusion

Exercise did not appear to affect RTclin performance in this study. This suggests that RTclin measured during a sideline concussion assessment does not need to be adjusted to account for the acute effects of exercise.

Keywords: Brain Concussion, Physical Exertion, Simple Reaction Time, Fatigue

Introduction

Impaired reaction time (RT) is a common and sensitive indicator of cognitive change following mild traumatic brain injury, or concussion (12,23). In the field of sports medicine, RT is commonly employed as part of a multifaceted concussion assessment battery, typically through use of a computerized neurocognitive test platform (8,10,25). RT is generally most prolonged immediately following injury and gradually returns to baseline over time, in parallel with the injured athlete's self-reported symptoms (6,11,13,28-32,37). RT has prognostic value in predicting an athlete's recovery following concussion and often remains impaired even after an athlete's symptoms have resolved (5,27,30,37). For these reasons, RT assessment can be valuable to the sports medicine practitioner, both during the acute assessment of a suspected concussion, and when making return to play decisions. The typical paradigm for using RT in the assessment of concussion is to compare an athlete's after-injury performance to their own baseline performance measured during their pre-participation physical examination before the start of the athletic season.

Unfortunately, currently available computerized methods of RT assessment are impractical for immediate use on the athletic sideline. To address this, we developed a clinical measure of simple RT, RTclin, which does not require a computer and can be used during the acute assessment of an injured athlete on the sideline or in the training room. Pilot work has demonstrated the reliability and validity of RTclin (18,19,22) as well as its sensitivity to concussion in the days following injury (17,20). In order to interpret changes from baseline in an athlete's RTclin performance immediately after an injury, the acute effects of exercise on RTclin must be understood and accounted for.

Simple RT is defined as the time delay between presentation of a single repeated stimulus and the initiation of a specific response to that stimulus (34), while choice RT is the time delay between the presentation of one of many stimuli and the initiation of a differing response to each specific stimulus (38). Many studies have investigated the effect of exercise on both simple and choice RT tasks. Welford (38) found an intermediate level of exercise, measured by heart rate, to be associated with subjects' optimal choice RT performance. Similarly, McMorris et al. (33) found that exercising below the lactate threshold (approximately 70% of VO2max), was associated with faster choice RT, while exercising above this threshold prolonged choice RT. Davranche et al. (15) identified a similar effect of exercise duration on choice RT. In this study, choice RT improved over the initial eight minutes of exercise, and became slower with sustained exercise beyond this point (26). Simple RT also appears to be influenced by the duration and intensity of exercise. For example, McMorris and Keen (34) demonstrated that cycling at 100% of maximum power output was associated with impaired simple RT. Other studies have illustrated a parabolic relationship between simple RT and cycling velocity (4). As a whole, these studies suggest that RT generally decreases (i.e., becomes faster) with moderately intense exercise, but increases (i.e., becomes slower) at more intense levels of physical exertion.

An athlete who sustains a concussion while participating in a game or practice session will commonly have been engaging in physical exercise immediately prior to their injury. Therefore, the effect of exercise on any acute concussion assessment measure should be understood and taken into account when making baseline to follow-up comparisons. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of exercise at differing levels of intensity on RTclin. We hypothesized that RTclin would decrease with exercise of moderate intensity and increase with more intense levels of exercise.

Methods

Subjects

Forty-two collegiate student-athletes (50% female) were recruited for this study and provided IRB-approved written informed consent prior to participating. Recruitment was based on a power analysis using estimated RTclin values from prior work by our group (17, 20), which suggested that a total of 39 participants would yield at least 80% power to detect a 10% difference in RTclin between the exercise and control groups at a significance level of α = 0.05. Forty-two athletes were therefore recruited to maintain gender balance with a 2:1 exercise:control group allocation ratio. To be eligible, participants had to be active members of a varsity collegiate athletics team. Potential subjects were excluded if they were acutely recovering from a concussion, or if they reported any disease or injury affecting their dominant hand that would preclude their successful completion of the RTclin task or any history of cardiac or pulmonary disease that would prevent their successful completion of the exercise protocol. Eligible athletes were instructed not to consume alcohol for at least 24 hours prior to their scheduled testing session.

Procedure overview

Participants were allocated into exercise and control groups in a 2:1 ratio using block randomization. Prior to testing, demographic information and basic sport-related concussion histories were obtained, and basic anthropometric measurements were taken. At each RTclin assessment point, heart rate (HR) was measured using a portable pulse oximeter and self-reported Borg rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale (2) was recorded to provide objective and subjective measures of exertion. After baseline RTclin, HR, and RPE measurements were taken, the exercise group completed a graded cycling protocol with repeated RTclin, HR, and RPE assessments after each phase, while the control group underwent identical reassessments at the same time intervals without intercurrent exercise. Figure 1 illustrates subject flow and the overall study procedure.

Figure 1. Flow chart illustrating the experiment protocol.

Clinical Reaction Time Testing

The device and procedure for testing RTclin have previously been described (18-20,22). Briefly, RTclin was measured using a rigid, cylindrical measuring stick coated in friction tape and affixed at one end to a weighted rubber disk to provide stability and standardize subject hand position. Athletes sat with their dominant forearm resting across the stationary bike's handle bars with their hand open in a wide, C-shaped open position. The examiner suspended the device vertically so that the disk rested inside the gap created by the athlete's open hand with top of the disk held level with the top of the athlete's first 2 digits. Athletes were instructed to focus their attention on the disk and to catch the apparatus as quickly as possible upon its release. The examiner released the device after suspending it, motionless, for random time intervals between 2 and 5 s, which prevented the athletes from being able to anticipate the time of device release. Figure 2 illustrates the RTclin device and procedure. The distance (in cm) the device fell before being caught was recorded and converted into a reaction time (in ms) using the formula relating position and time for an object in free fall (d=1/2gt2). After 2 practice trials, a mean (± SD) RTclin value was calculated over 8 individual trials at each assessment point.

Figure 2. Demonstration of RTclin device and testing procedure on stationary bike.

Exercise and Control Protocols

Participants in the exercise group (n=28) completed a modified Bruce protocol, adapted from Ando et. al (1). This cycle-based procedure was designed to incrementally increase the athletes' exercise intensity over 4 stages. After completing their baseline assessments, these athletes warmed up for 3 minutes by cycling at a power output of 50W and then immediately began stage 1, which consisted of cycling for 5 minutes at a power output of 100W. During the second and third stages, the athletes increased their power output to 150W and 200W, respectively, for 5 minutes each. The fourth stage was a sprint during which the athletes were instructed to pedal as fast as they could (>200W power output) for 2 minutes. RTclin, HR, and RPE were reassessed immediately after each stage, while the athletes remained seated on the exercise bike. After the final reassessments, participants cooled down for 5 minutes at a self-selected comfortable pace. Participants in the non-exercise control group (n=14) completed identical repeated RTclin, HR, and RPE assessments while seated on the stationary bike, but instead of exercising, rested quietly for equivalent periods of time.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and concussion history and compared between the exercise and control groups using t-tests and chi-square tests, as appropriate. A t-test was also used to compare baseline RTclin between the exercise and control groups. We used SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) PROC MIXED to conduct a repeated measure analysis of variance to determine the effect of exercise on RTclin, controlling for gender, baseline heart rate, and repeated test administrations.

Results

Twenty-one male American football players, as well as 12 women's soccer players, 5 women's gymnasts, 2 women's basketball players, and 2 women's volleyball players participated. The gender-balanced exercise and control groups were similar in age (19.6 ± 1.1 vs. 20.1 ± 1.7 years; p = 0.276), height (70.5 ± 5.2 vs. 70.7 ± 5.0 inches; p = 0.882), weight (193.8 ± 64.2 vs. 190.8 ± 61.2 pounds; p = 0.885), BMI (26.8 ± 5.9 vs. 26.2 ± 5.5; p = 0.780), resting heart rate (81.0 ± 14.3 vs. 77.4 ± 9.6 beats/min; p = 0.341), and concussion history (21.4% vs. 35.7%; p = 0.321). The cycling protocol was effective at increasing both participants' heart rate (p < .001) and rate of perceived exertion (p <.001). The effect of the exercise protocol on heart rate and rate of perceived exertion is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. HR and RPE by assessment point for exercise and control groups; error bars represent SEM.

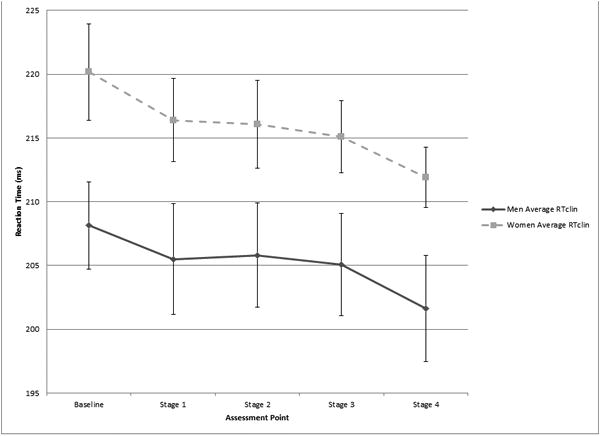

The exercise and control groups demonstrated no differences in RTclin at baseline (214 ± 18 vs. 214 ± 17 ms; p = 0.871). Adjusting for gender and baseline heart rate, repeated test administration had a significant effect on mean RTclin, with a decrease over repeated test administrations (main order effect, p = 0.008; Figure 4). However, no main exercise effect (difference between exercise group vs. control group; p = 0.822) or exercise-by-observation interaction effect (difference in the rate of change in RTclin over repeated test administrations between the exercise group vs. control group; p = 0.169) was present (Figure 4). A main effect for gender was observed (p = 0.049), with faster mean RTclin values observed in males than females (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Mean RTclin values by assessment point for exercise and control groups; error bars represent SEM.

Figure 5. Mean RTclin values by assessment point for males and females; error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not identify an exercise effect on RTclin. While inspection of Figure 4 does suggest a possible difference in RTclin results between the exercise and control groups after Stage 1, this small difference failed to reach statistical significance (216 ± 17 vs. 208 ± 19 ms; p = 0.167). Closer inspection of the data demonstrates that the 8 ms difference between the exercise and control groups after Stage 1 was more driven by 2 outliers in the control group whose Stage 1 RTclin values were 30 and 38 ms slower than their own baseline RTclin values than by an overall improvement in Stage 1 RTclin in the exercise group. These outliers account for this difference by effectively increasing the mean Stage 1 RTclin value in the control group, as opposed to a decreased Stage 1 RTclin value in the exercise group as we hypothesized would occur. Furthermore, the magnitude of these changes is relatively small. Using Cohen's d to estimate effect sizes, the magnitude of the changes in RTclin from baseline to stage 1in the exercise and control groups were d = -0.324 and d = 0.118, respectively, which are generally considered small (9). In comparison, the magnitude of change in RTclin following acute concussion has previously been reported to range from d = 0.616 to d = 1.03, (17,20) which are generally considered medium to large (9).

While the majority of the literature describing the effect of exercise on RT tasks suggests that RT is enhanced by moderately intense exercise (35), this finding is not universal. Tsorbatzoudis et al. (36) reported similar results to our own. In this study, simple RT was neither significantly affected by the intensity nor the duration of physical exertion, but a learning effect did appear to be present in both the exercise and control groups. In comparison, Hogervorst et al. (24) investigated changes in simple reaction time after exertion rather than during. They reported an improvement in simple RT after exertion, but were unable to conclude whether this finding was attributable to an enhancement of central nervous system processing speed with exercise or a learning effect. In a different study, Brisswalter and Arcelin (3) reported a negative influence of exercise on simple RT during exercise, but found no differences between groups just one minute after exercise was completed.

Although no exercise effect was observed in this study, our data do support both gender and order effects on RTclin, The gender effect identified in this study has been previously reported for RTclin (21), and is consistent with other RT studies in athletes demonstrating faster RT for males than females (e.gs.,7,14). While the male athletes had significantly faster RTclin results than the female athletes in this study, this difference should not have influenced the primary RTclin comparison between the exercise and control groups since the groups were balanced with respect to gender. The overall improvement in RTclin results over subsequent test administrations suggests the presence of a learning effect for the test. While not universally present in prior studies investigating RTclin, a possible learning effect has been observed over 8 RTclin trials (18), from pre-season to mid-season reassessments (17), and over a 1-year re-test interval (19). Additional practice trials during an athlete's initial assessment may mitigate the potential learning effect associated with RTclin (21) by causing it to “wash out” before more stable RTclin data are achieved and ultimately recorded for analysis. Future research designed to clarify the optimal number of practice trails during initial RTclin assessment may further guide its most effective use in sports medicine practice.

This study has several limitations that are worthy of mention. First, all of the study participants were collegiate athletes, and therefore these results may not be representative of other athlete populations, such as youth, high-school, and recreational athletes. In addition, the standardized exercise protocol used in this study involved stationary bike riding but none of the study participants were competitive cyclers. We do not suspect that individualizing the exercise protocols for each participant's chosen sport would affect the overall study results, however the true effects of a sport-specific exercise intervention are unknown. Furthermore, other factors that were not directly measured or controlled for by our protocol, such as motivation and effort, are known to affect RT performance. However, we have previously demonstrated that the performance feedback inherently provided by the RTclin test is motivating (16). Also, randomized allocation of subjects to the exercise and control groups should minimize any effect of these and other unmeasured variables on our results. Finally, while it was our intention that athletes would be engaged in anaerobic exercise during the final two minute sprint of Stage 4, we did not directly measure any markers of aerobic vs. anaerobic metabolism. As such, we cannot definitively state that our results apply equally to both aerobic and anaerobic exercise, although we do suspect this to be the case.

In conclusion, this study does not support an exercise effect on RTclin in athletes. Prior work has demonstrated RTclin to be a reliable and valid measure of reaction time in athletes that is both sensitive to the effects of concussion and predictive of an athlete's ability to perform head protective maneuvers. These results suggest that no exercise correction is necessary when interpreting follow-up RTclin results in an athlete with suspected concussion who has been exercising. These features, as well as the ease and low cost associated with RTclin, support its use as part of the sports medicine practitioner's concussion assessment battery.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Steven Nordwall and his athletic training staff for their assistance in recruiting athletes for this study. Dr. Eckner thanks the Rehabilitation Medicine Scientist Training Program (2K12HD001097-16) for its mentoring and support.

Disclosure of Funding: Dr. Eckner is supported by a career development award from the Rehabilitation Medicine Scientist Training Program (2K12HD001097-16).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The University of Michigan has applied for a provisional patent for a reaction time device that is similar to the one described in this article, on which Dr. Eckner is listed as a co-inventor. At this time, no professional, financial, or commercial relationships with any companies or manufacturers exist related to this patent application.

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

References

- 1.Ando S, Yamada Y, Kokubu M. Reaction time to peripheral visual stimuli during exercise under hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1210–6. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01115.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brisswalter J, Arcelin R. Influence of physical exercise on simple reaction time: effect of physical fitness. Percpt Mot Skills. 1997;85:1019–27. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.85.3.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisswalter J, Durand M, Delignieres D, Legros P. Optimal and non-optimal demand in a dual task of pedaling and simple reaction time: effects on energy expenditure and cognitive performance. J Hum Move Stud. 1995;29:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broglio SP, Macciocchi SN, Ferrara MS. Neurocognitive performance of concussed athletes when symptom free. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):504–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broglio SP, Sosnoff JJ, Ferrara MS. The relationship of athlete-reported concussion symptoms and objective measures of neurocognitive function and postural control. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(5):377–82. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181b625fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown AM, Kenwell ZR, Maraj BK, Collins DF. “Go” signal intensity influences the sprint start. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(6):1142–8. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816770e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cernich A, Reeves D, Sun W, Bleiberg J. Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics sports medicine battery. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22S1:S101–14. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis ofr the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assocites, Inc.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collie A, Maruff P, Darby D, Makdissi M, McCrory P, McStephen M. CogSport. In: Echemendia RJ, editor. editor Sports Neuropsychology: Assessment and Management of Traumatic Brain Injury. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 240–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collie A, Makdissi M, Maruff P, Bennell K, McCrory P. Cognition in the days following concussion: comparison of symptomatic versus asymptomatic athletes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):241–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.073155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collie A, Maruff P, Makdissi M, McCrory P, McStephen M, Darby D. CogSport: reliability and correlation with conventional cognitive tests used in postconcussion medical evaluations. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(1):28–32. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins MW, Field M, Lovell MR, Iverson G, Johnston KM, Maroon J, Fu FH. Relationship between postconcussion headache and neuropsychological test performance in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(2):168–73. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dane S, Erzurumluoglu A. Sex and handedness differences in eye-hand visual reaction times in handball players. Int J Neurosci. 2003;113(7):923–9. doi: 10.1080/00207450390220367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davranche K, Audiffren M, Deniean A. A distributional analysis of the effect of physical exercise on a choice reaction time task. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(3):323–9. doi: 10.1080/02640410500132165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckner JT, Chandran S, Richardson JK. Investigating the role of feedback and motivation in clinical reaction time assessment. PM R. 2011;3(12):1092–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, Broglio SP, Richardson JK. Effect of sport related concussion on clinically measured simple reaction time. Br J Sports Med. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091579. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, Richardson JK. Pilot evaluation of a novel clinical test of reaction time in national collegiate athletic association division I football players. J Athl Train. 2010;45(4):327–32. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, Richardson JK. Between-seasons test-retest reliability of clinically measured reaction time in national collegiate athletic association division I athletes. J Athl Train. 2011;46(4):409–14. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, Richardson JK. Effect of concussion on clinically measured reaction time in nine NCAA Division I collegiate athletes: a preliminary study. PM R. 2011;3:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckner JT, Lipps DB, Kim H, Richardson JK, Ashton-Miller JA. Can a clinical test of reaction time predict a functional head-protective response. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(3):382–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f1cc51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckner JT, Whitacre RD, Kirsch M, Richardson JK. Evaluating a clinical measure of reaction time: an observational study. Percept Mot Skills. 2009;108:717–20. doi: 10.2466/PMS.108.3.717-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlanger D, Saliba E, Barth J, Almquist J, Webright W, Freeman J. Monitoring resolution of postconcussion symptoms in athletes: preliminary results of a web-based neuropsychological test protocol. J Athl Train. 2001;36(3):280–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogervorst E, Riedel W, Jeukendrup A, Jolles J. Cognitive performance after strenuous physical exercise. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;83:479–88. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iverson GL, Lovell MR, Collins MW. Validity of ImPACT for measuring processing speed following sports-related concussion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27(6):683–9. doi: 10.1081/13803390490918435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashihara K, Nakahara Y. Short-term effect of physical exercise at lactate threshold on choice reaction time. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;100:275–91. doi: 10.2466/pms.100.2.275-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau B, Lovell MR, Collins MW, Pardini J. Neurocognitive and symptom predictors of recovery in high school athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(3):216–21. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31819d6edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovell M, Collins M, Fu F, Burke C, Maroon J, Podell K, Powell J. Neuropsychological testing in sports: past, present, and future. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:373. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makdissi M, Collie A, Maruff P, Darby DG, Bush A, McCrory P, Bennell K. Computerised cognitive assessment of concussed Australian Rules footballers. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(5):354–60. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.5.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makdissi M, Darby D, Maruff P, Ugoni A, Brukner P, McCrory PR. Natural history of concussion in sport: markers of severity and implications for management. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(3):464–71. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClincy MP, Lovell MR, Pardini J, Collins MW, Spore MK. Recovery from sports concussion in high school and collegiate athletes. Brain Inj. 2006;20(1):33–9. doi: 10.1080/02699050500309817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCrea M, Prichep L, Powell MR, Chabot R, Barr WB. Acute effects and recovery after sport-related concussion: a neurocognitive and quantitative brain electrical activity study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25(4):283–92. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181e67923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMorris T, Graydon J. The effect of incremental exercise on cognitive performance. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000;31(1):66–81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMorris T, Keen P. Effect of exercise on simple reaction times of recreational athletes. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78:123–30. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomporowski P. Effect of acute bouts of exercise on cognition. Acta Psychol. 2003;112:297–324. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(02)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsorbatzoudis H, Barkoukis V, Danis A, Grouios G. Physical exertion in simple reaction time and continuous attention of sports participants'. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;86:571–6. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.86.2.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warden DL, Bleiberg J, Cameron KL, Ecklund J, Walter J, Sparling MB, Arciero R. Persistent prolongation of simple reaction time in sports concussion. Neurology. 2001;57(3):524–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welford AT. Choice reaction time: basic concepts. In: Welford AT, editor. Reaction Times. New York (NY): Academic Press; 1980. pp. 73–128. [Google Scholar]