Abstract

Characterizing novel drugs and chemical probes of biological systems is hindered by difficulties in identifying the mechanism of action (MOA) of biologically active molecules. Here we present a metabolite suppression approach to explore the MOA of antibacterial compounds under nutrient restriction. We assembled an array of metabolites that can be screened for suppressors of inhibitory molecules. Further, we identified inhibitors of E. coli growth under nutrient limitation and charted their interactions with our metabolite array. This strategy led to the discovery and characterization of three novel antibacterial compounds, MAC168425, MAC173979 and MAC13772. We showed that MAC168425 interferes with glycine metabolism, MAC173979 is a time-dependent inhibitor of p-aminobenzoic acid biosynthesis and MAC13772 inhibits biotin biosynthesis. We conclude that metabolite suppression profiling is an effective approach to focus MOA studies on compounds impairing metabolic capabilities. Such bioactives can serve as chemical probes of bacterial physiology and as leads for antibacterial drug development.

INTRODUCTION

The alarming spread of multidrug resistance is due in part to the fact that existing antibiotics target a very limited number of pathways, namely cell wall, DNA and protein biosynthesis1,2. There has been rising concern in the past decade about the general lack of innovation in the discovery of novel antibacterials3 stressing the need for exploring less conventional antimicrobial targets.

The past decade has produced remarkable developments in microbial genomics, target validation and screening technology that have provided drug discoverers with many avenues to identify novel antibacterials4. Moreover, given the challenges faced when attempting to convert inhibitors of recombinant targets into cell-active compounds, recent antibacterial drug discovery campaigns are shifting towards phenotype-based screening4. However, linking the phenotype(s) caused by biologically active small molecules to specific mechanisms remains one of the biggest roadblocks in cell-based screening5.

In this respect, chemical genomic strategies have had considerable success in uncovering the MOA of biologically active molecules. Most significant are efforts in the characterization of the MOA of small molecules by exploring their effects on genome-scale overexpression and deletion clone sets6–9. We have reported on manipulating gene dosage in E. coli as a systematic strategy towards identifying the cellular targets of novel antibacterials and describing uncharted chemical genetic interactions for known antibiotics10,11.

In this work, we describe an approach that relies on using differential media screening as a strategy to explore the MOA of small molecules that inhibit bacterial growth under nutrient-limited conditions. When bacteria are grown in minimal media, they undergo a significant shift in their metabolic activities to support the requirements for de novo synthesis of amino acids, precursor molecules, vitamins and other cofactors12–14. Indeed, only 303 genes are essential for growth of wild type E. coli on rich media and some 119 genes are additionally required for growth on nutrient-limited media15.

Small molecules that specifically target bacteria under nutrient limitation could serve as mechanistic probes to address biological questions about nutritional stress responses. Moreover, some of these bioactives could be potential leads for the development of novel antimicrobials. There have been many reports of impaired growth and attenuated virulence of various pathogens due to auxotrophy-generating gene deletions16–21. Combination therapy with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, two inhibitors of folate biosynthesis, remains one of the most effective treatments for respiratory and urinary tract infections22 and clearly validates targeting bacterial biosynthetic pathways in antibacterial therapy. Nevertheless, systematic searches for antibacterial chemicals have overwhelmingly emphasized rich nutrient conditions.

Metabolite supplementation has proven to be a formidable approach to understanding metabolic pathways in model microbes23. Herein we have exploited its power to investigate the MOA of biologically active small molecules. This strategy significantly narrows the number of potential targets to the benefit of mechanistic investigations. We have applied this approach to explore the antibacterial activity of both known antibiotics and novel antibacterial compounds identified from a high-throughput screen of growth inhibition of E. coli under nutrient limitation. Through this approach we generated characteristic fingerprints of small molecule-metabolite interactions that could inform on their biological activity. We report on the discovery of three novel antibacterial compounds: MAC168425 which elicits its activity by interfering with glycine metabolism, MAC173979, a unique time-dependent inhibitor of p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) biosynthesis and MAC13772, an inhibitor of the enzyme BioA, the antepenultimate step in biotin biosynthesis. These inhibitors can serve both as specific chemical probes to study metabolic pathways in bacteria at a systems-level and as potential leads for antibiotic drug discovery.

RESULTS

Screening for inhibitors in nutrient-deficient media

A flow chart that outlines the different stages of our approach is shown in Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1. Our work began with a high-throughput screen to identify compounds with growth inhibitory activity at a concentration of 10 μM against E. coli MG1655 in nutrient-deficient media from a library of ~ 30,000 molecules. This library includes structurally diverse small synthetic molecules, off-patent FDA-approved and pharmacologically active molecules as well as purified natural products (See Online methods).

The primary screen was of high quality with respect to signal, noise and reproducibility as shown in the control (Supplementary Fig. 2) and compound (Fig. 1a) data. The statistical parameter Z′ describes the window between high and low controls and provides a measure to evaluate the quality of the screen24. For this screen, the average Z′ value was 0.8. A cutoff of 80% residual growth was determined by calculating 3 standard deviations from the high controls below 100% residual growth. This cutoff identified 496 actives that resulted in at least 20% growth inhibition relative to the high controls, corresponding to a hit rate of 1.7% (Fig. 1a). After eliminating known antibiotics we arrived at a set of 340 novel active compounds for further study. These were mainly synthetic small molecules constituting a set of novel chemical scaffolds with largely uncharacterized biological activity. In addition, there were a small number of natural products. Of the 340 compound selected for follow up, there was about a 7% false positive rate.

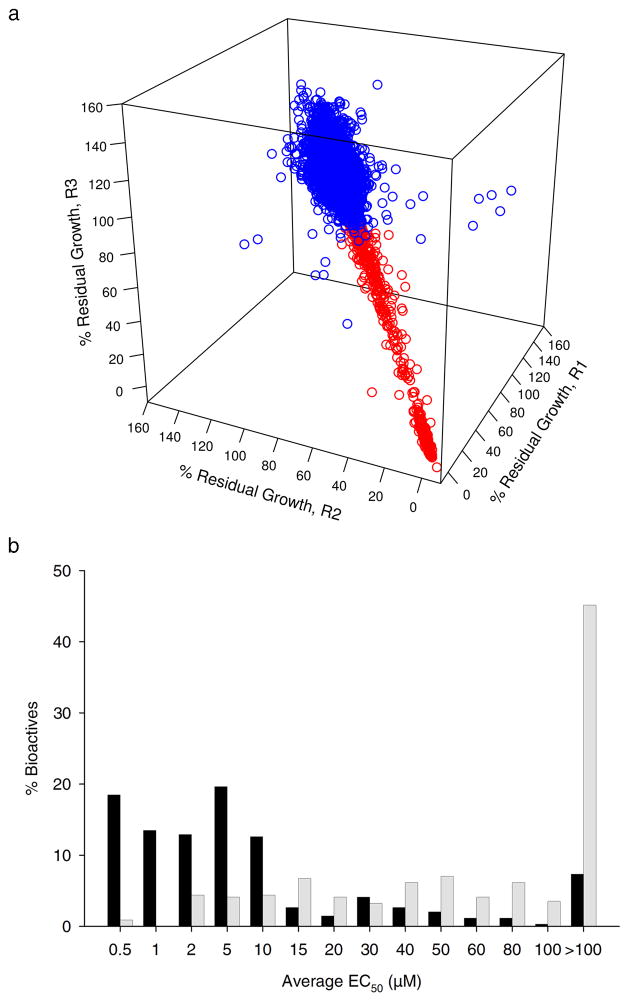

Figure 1. Primary small molecule screen in minimal media and EC50 evaluation of novel bioactives.

(a) 3D replicate plot of the primary screen of ~ 30,000 small molecules against E. coli MG1655 grown in M9 minimal media. Bacterial growth in the test wells is expressed as a percentage relative to the growth in the control wells (Supplementary Fig. 2). The percent residual growth (%RG) of each replicate is plotted on each axis. Data points that fall on a slope of 1 are considered reproducible. Molecules that resulted in a residual growth below 80% for each replicate relative to the control wells were identified as biologically active against E. coli MG1655 in minimal media (red circles) and were selected for further study (496 molecules). (b) Histogram of the average EC50 values obtained from the dose-response analysis of 340 novel actives conducted in minimal (black bars) and supplemented minimal media (grey bars). EC50 values were determined in duplicate in each media condition (See Online methods and Supplementary Table 3).

Differential media screening

To prioritize compounds that are specifically active under nutrient limitation, we conducted dose-response evaluations for all 340 compounds in nutrient-limited and in defined rich media supplemented with a mix of amino acids, purines, pyrimidines and vitamins (See Online methods and Supplementary Table 2). These data were used to prioritize a subset of bioactives that perturbed bacterial physiology under nutrient-limited conditions. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows examples of the assessment for two compounds. Interestingly, nearly a third of the 340 tested compounds exhibited a significant difference in potency against E. coli grown in the two different media. In fact, as many as 45% of the compounds showed no inhibition of bacterial growth within the tested concentration range in defined rich media in contrast to only 7% of the compounds with no activity against E. coli in minimal media (Fig. 1b). Based largely on the potency and specificity to nutrient-limited conditions, we prioritized a total of 74 actives for follow up analysis (EC50 and MIC values are listed in Supplementary Table 3).

Metabolic suppression profiling

The strategy presented herein relies on perturbation using small molecules in a way that mimics genetic mutations in auxotrophic strains. To this end, we developed a secondary screen in which chemical complementation with metabolites was used as a rational approach to identify the potential cellular pathway(s) targeted by the actives prioritized from the primary screen.

In this secondary screen, growth of E. coli in minimal media containing an inhibitory concentration of each tested compound was examined against an array of single primary metabolites (amino acids, vitamins and nucleobases) and pools thereof (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The clustered heat map in Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the metabolic suppression profile of the 74 prioritized actives and a set of known antibiotics with different MOA as controls to validate the approach. The profiles of a representative set of 24 inhibitors are shown in Fig. 2.

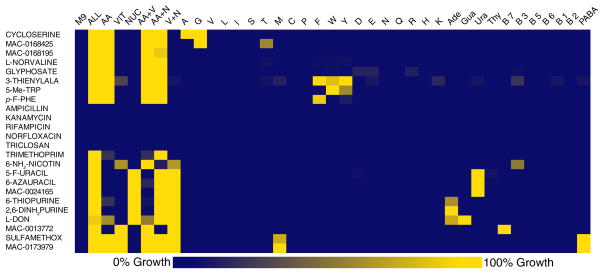

Figure 2. Metabolic suppression profiles of antibacterial inhibitors.

The metabolic suppression profiles of a representative set of 24 antibacterial inhibitors including 19 known antibiotics from Supplementary Fig. 5 are shown in this heat map. Growth of E. coli MG1655 is measured in the presence of each inhibitor with various primary metabolites or pools of metabolites in the metabolic suppression array (n= 2 replicates) (See Online methods and Supplementary Fig. 4). Actives identified from the primary screen are designated by their MAC ID and known actives by their names. Amino acids are referred to by their 1-letter code, B vitamins by their respective numbers, PABA: p-aminobenzoic acid, Ade: adenine, Gua: guanine, Ura: uracil, Thy: thymine. M9: no supplements; ALL: all supplements; AA: all amino acids; VIT: all vitamins; NUC: all nucleobases; 3-THIENYLALA: L-3-thienylalanine, 5-Me-TRP: 5-methyltryptophan, p-F-PHE: p-fluorophenylalanine,, 6-NH2NICOTIN: 6-aminonicotinamide, 5-F-URACIL: 5-fluorouracil, 2,6-DINH2-PUR: 2,6-diaminopurine, L-DON: 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine, SULFAMETHOX: sulfamethoxazole.

The patterns of interaction between metabolites and inhibitors create unique metabolic suppression fingerprints that can be used to guide hypotheses regarding their MOA. The heat map in Supplementary Fig. 5 is clustered based on these metabolic suppression fingerprints so that compounds with similar profiles are grouped within the same cluster.

Metabolic suppression profiles of known antibiotics

The metabolic suppression profiles of 22 known antibiotics of diverse MOA demonstrate the power of this approach (Supplementary Fig. 6). Noteworthy is that the activity of known antibiotics with mechanisms that do not directly involve primary metabolism such as replication, transcription and translation inhibitors was not altered in the presence of supplements. Inhibitors targeting biosynthetic capabilities on the other hand displayed distinct metabolic suppression phenotypes mainly pertaining to their transport and/or MOA. Antimetabolites like 5-fluoruracil and 6-azauracil, which inhibit different steps in pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis were suppressed by uracil25,26. Growth inhibition by 6-aminonicotinamide was antagonized by niacin27; 6-thiopurine and 2,6-diaminopurine by purine nucleobases. The actions of 3-thienylalanine, 5-methyltryptophan and p-fluorophenylalanine were reversed in the presence of aromatic amino acids28. The activity of the natural product 6-diazo-5-oxonorleucine which targets several glutamine-utilizing enzymes in various metabolic pathways was primarily suppressed by purine nucleobases29–31.

The cell wall inhibitor D-cycloserine was suppressed by either D,L-alanine or glycine. D-cycloserine, D-alanine and glycine use the same import mechanism encoded by the transporter cycA32. Inside the cell, D-cycloserine is a competitive inhibitor of D-alanine-D-alanine ligase (Ddl) in peptidoglycan biosynthesis33,34 and of D-alanine racemase (DadX) which catalyzes the interconversion of D- and L-alanine35.

Inhibition by the anti-folate antibiotic sulfamethoxazole was fully reversed by p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) and to an extent by methionine, a signature profile of inhibitors of PABA metabolism36. The enzymes PabA, PabB and PabC catalyze the biosynthesis of PABA from chorismate23. PABA is a precursor of folate coenzymes which are involved in the transfer of one-carbon units in several pathways including the biosynthesis of methionine, purines and pyrimidines37 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Sulfamethoxazole and other sulfa drugs compete with PABA at the step of dihydropteroate synthesis (FolP) and enter the pathway as alternate substrates ultimately creating dead-end products38. Addition of PABA outcompetes sulfamethoxazole while methionine supplementation provides a major metabolite dependent on folate cofactors37.

Trimethoprim targets dihydrofolate reductase (FolA) which catalyzes the synthesis of tetrahydrofolate (Supplementary Fig. 7). Since folate coenzymes are essential for the biosynthesis of glycine, methionine, pantothenate, formylated methionine, purine and pyrimidine nucleotides37, growth inhibition by trimethoprim could only be suppressed by providing a mixture of amino acids and nucleobases (Supplementary Fig. 6). The herbicide glyphosate inhibits 5-enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (AroA)39, which is involved in the biosynthesis of chorismate, a precursor of several metabolites including the aromatic amino acids, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan (Supplementary Fig. 8a)23. Accordingly, suppression of the activity of glyphosate could only be achieved by providing a mixture of amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

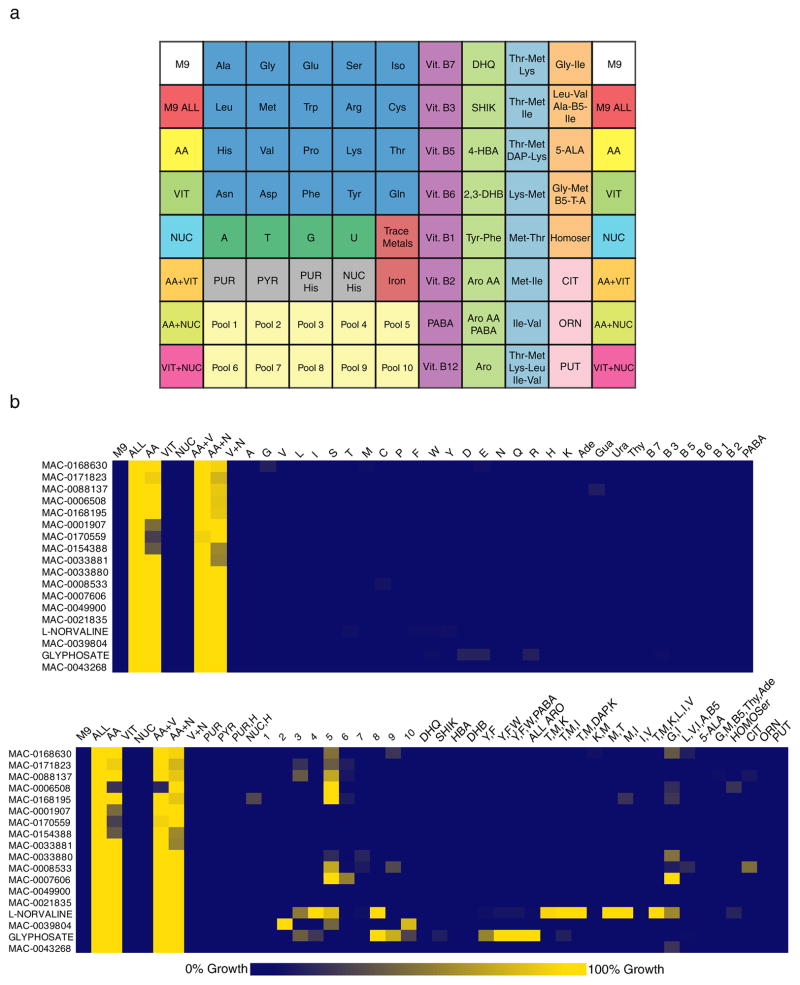

Metabolic suppression fingerprints where growth inhibition could only be reversed by a pool of metabolites were observed for about 20% of the profiled priority actives (Supplementary Fig. 5). This revealed the need to enrich the array with additional pools of metabolites that would, for example, accommodate blocks in early steps of branched metabolic pathways where more than one supplement would be required for suppression. In principle, the number of possible combinations of metabolites is very large. Nevertheless, a survey of primary metabolism in E. coli revealed a number of precedented supplements including pathway intermediates and metabolite pools. Thus we created an expanded metabolic suppression array (Fig. 3a) where, for example, a mixture of aromatic amino acids fully reversed inhibition by glyphosate (Supplementary Fig. 8c). After profiling with the expanded metabolic suppression array, the activity of over half of the actives not suppressed by single supplements were further elaborated with suppression phenotypes using various pools of metabolites (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Pools of metabolites reveal more complex metabolic suppression patterns.

(a) The Expanded Metabolic Suppression Array. Amino acids are referred to by their 3-letter code, nucleotides by their 1-letter code, PABA: p-aminobenzoic acid. M9: no supplements; ALL: all supplements; AA: all amino acids; VIT: all vitamins; NUC: all nucleobases; PUR: purine nucleobases; PYR: pyrimidine nucleobases; DHQ: 3-dehydroquinic acid; SHIK: shikimic acid; 4-HBA: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid; 2,3-DHB: 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid; Aro AA: aromatic amino acids (Phe, Tyr, Trp); Aro: aromatic amino acids, p-aminobenzoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid; DAP: diaminopimelic acid; 5-ALA: 5-aminlevulinic acid; Homoser: homoserine; CIT: citrulline; ORN: ornithine; PUT: putrescine. For more details, see Online methods and Supplementary Table 2.

(b) Top panel: Cluster from the heat map in Supplementary Fig. 5 showing the metabolic suppression profiles of 18 inhibitors evaluated against the metabolic suppression array (Supplementary Fig. 4). The legend is the same as in Fig. 2. Bottom panel: The metabolic suppression profile of the same inhibitors in the top panel after being evaluated against the expanded metabolic suppression array (n= 2 replicates). The legend is the same as in Fig. 2 in addition to PUR: purine nucleobases; PYR: pyrimidine nucleobases; DHQ: dihydroquinone; SHIK: shikimic acid; HBA: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid; DHB: 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid; ALL ARO: aromatic amino acids, p-aminobenzoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid; DAP: diaminopimelic acid; 5-ALA: 5-aminlevulinic acid; HOMOser: homoserine; CIT: citrulline; ORN: ornithine; PUT: putrescine; Pools 1–10 are described in Supplementary Table 2.

MAC168425 interferes with glycine metabolism in E. coli

One of the clusters in the heat map in Supplementary Fig. 5 includes the profiles of 7 priority actives that were strongly suppressed by the amino acid glycine (Supplementary Fig. 9). The activity of one of the molecules, MAC168425 (1) was strongly suppressed by glycine and to a lesser extent by L-threonine (Supplementary Fig. 10). In E. coli, glycine is primarily synthesized from serine in a one-step reaction catalyzed by serine-hydroxymethyl transferase (GlyA). This reaction is not only a source of glycine for protein synthesis but also the major source of one-carbon units needed for the synthesis of methionine, thymine, purines and pantothenate40. Threonine catabolism also contributes to the cellular pool of glycine. In the major pathway, threonine is converted to glycine through the action of threonine dehydrogenase (Tdh) and α-amino-β-ketobutyrate lyase (Kbl) (Supplementary Fig. 11a)40. In the minor pathway, low-specificity threonine aldolase (LtaE) degrades threonine to form glycine and acetaldehyde (Supplementary Fig. 11b)41. Given that MAC168425 is strongly suppressed by glycine, partially suppressed by L-threonine and not suppressed by L-serine, we hypothesized that the connectivity between L-threonine and glycine metabolism underlies this metabolic suppression profile.

To test this, suppression of the activity of MAC168425 by L-threonine was tested in strains impaired in the threonine degradation pathways (Supplementary Fig. 11c). In the wild-type strain, MAC168425 has a 4- to 8-fold shift in its MIC in the presence of 40 to 640 μg/ml of L-threonine. Within this range, L-threonine is generally less effective at suppressing growth inhibition by MAC168425 in a Δtdh mutant compared to a ΔltaE mutant. In a double deletion strain deficient in both the major and minor pathways (ΔltaEΔtdh), the activity of MAC168425 is only suppressed at the highest concentrations of L-threonine tested (320–640 μg/ml) sustaining a 2-fold shift in its MIC. In a triple deletion mutant strain (ΔltaEΔtdhΔkbl), suppression of the activity of MAC168425 is completely lost. It should be noted that the double and triple deletion mutants grow similarly to the wild-type parent strain and to the single deletion mutants (Supplementary Fig. 11d). These data strongly support the hypothesis that suppression of the lethality of MAC168425 by L-threonine is mediated through its conversion to glycine inside the cell and that the activity of this inhibitor likely centers on reactions involving glycine production or utilization.

MAC173979 inhibits PABA biosynthesis in E. coli.

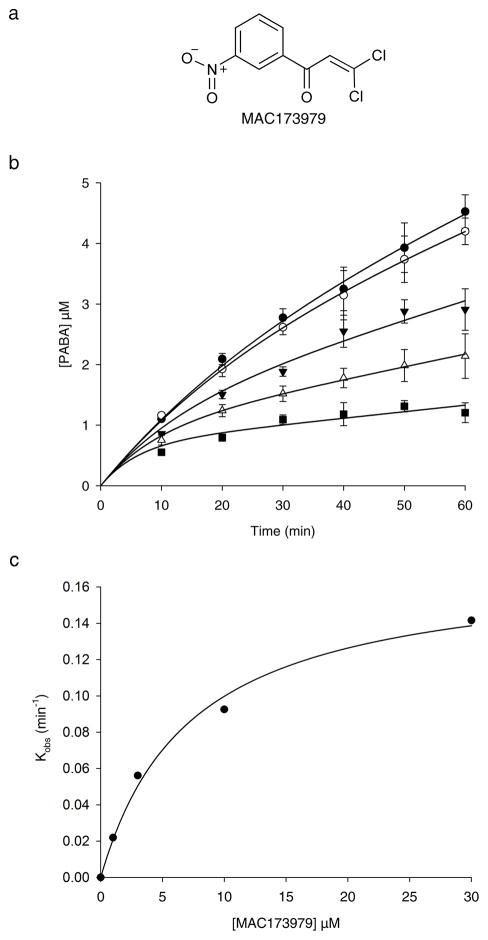

One of the major clusters in the heat map in Supplementary Fig. 5 groups the metabolic suppression profiles of 15 priority actives with that of sulfamethoxazole (Supplementary Fig. 12). These compounds were suppressed when PABA, or to an extent methionine, were present in the growth media and all but one of these contain the p-aminobenzenesulfonamide moiety of sulfa drugs (Supplementary Fig. 13). The exception was the inhibitor MAC173979 (2), a dichloro-nitrophenyl propenone (Fig. 4a). Both PABA and methionine fully reversed the activity of MAC173979 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Indeed, the addition of PABA resulted in a 16-fold suppression of its MIC (Supplementary Fig. 15a) which was not observed with other metabolites derived from chorismate (Supplementary Fig. 15b). We hypothesized that MAC173979 could inhibit the folate pathway at the branch of PABA biosynthesis. PABA is synthesized from chorismate and L-glutamine in two steps catalyzed by three enzymes, PabA, PabB and PabC (Supplementary Fig. 15c)37. We reconstituted PABA synthesis with an HPLC-UV-based one-pot assay using recombinant PabA, PabB and PabC (Supplementary Fig. 15d). On addition of a mixture of enzymes to initiate the synthesis of PABA from chorismate and L-glutamine in the presence of different concentrations of MAC173979, the resulting reaction progress curves followed a curvilinear trend whereby each curve reached a slower steady-state rate after a fast initial velocity (Fig 4b). This is characteristic of time-dependent enzyme inhibition42.

Figure 4. MAC173979 is an inhibitor of PABA biosynthesis in E. coli.

(a) Chemical structure of MAC173979. (b) Progress curves of the production of PABA in the presence of 0 (closed circles), 1 μM (open circles), 3 μM (closed triangles), 10 μM (open triangles) and 30 μM (closed squares) of MAC173979. The assay was conducted by monitoring the conversion of chorismate to PABA in a one-pot enzyme assay of recombinant PabA-B-C complex using HPLC (See Supplementary Fig. 15d). The data represent the averages of 3 replicates ± s.d. and the progress curves are globally fitted to the rate equation of slow-binding inhibition42 (See Online methods). (c) The plot of kobs as a function of [MAC173979] fits a hyperbolic function suggesting a mechanism of inhibition where the initial EI complex is formed rapidly and then followed by a second slower conformational change to form the inactive EI* complex (See Supplementary Fig. 16). The data best fit the hyperbolic function defined by the equation which suggests that MAC173979 acts as an irreversible time-dependent inhibitor with an apparent Ki of 7.3 ± 1.3 μM (See Online methods).

In principle, time-dependent enzyme inhibitors can follow either a simple reversible inhibition model or a two-step isomerization model (Supplementary Fig. 16). In the first mechanism, formation of the EI complex occurs in a single step on a slow time scale relative to the enzyme turnover. In the second, the EI complex undergoes a slower conformational change to form an inactive EI* complex. When the dissociation constant of the EI* complex is so low it approaches zero, the inhibitor is for all practical considerations irreversible42,43. The relationship between the inhibitor concentration and kobs, the apparent first order rate constant for the interconversion between the initial and steady-state rates, can help distinguish between the different mechanisms of inhibition. A plot of kobs versus [I] will be linear for the simple reversible model and hyperbolic for the slow isomerization model. Fig. 4c shows that the plot of the kobs values versus [MAC173979] fits a hyperbolic function consistent with a mechanism of time-dependent inhibition that involves an isomerization of the EI complex. In order to discern whether there is an appreciable dissociation of the EI* complex that contributes to the inhibition mechanism, the data were fit to two hyperbolic functions defined by the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Equation (2) provided the best fit for the experimental data, suggesting that MAC173979 acts as an irreversible time-dependent inhibitor of PABA synthesis with an apparent Ki of 7.3 ± 1.3 μM. Given that MAC173979 contains a Michael acceptor conjugated to highly electron-withdrawing groups (Fig. 4a), we reasoned that it could be susceptible to attack by an active site nucleophile with one of the two chlorines acting as a leaving group. However, when we determined the IC50 of MAC173979 and an analog lacking the Michael acceptor, MAC173979-D (3) against the PabA-B-C system, we found them to be 30 ± 2 μM and 60 ± 7 μM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 17a, b and c). Thus while covalent chemistry cannot be ruled out at other potential sites of reactivity on this molecule, it remains an interesting possibility that MAC173979 is a non-covalent, time-dependent inhibitor with a dissociation constant so low that it appears irreversible.

MAC13772 inhibits biotin biosynthesis in E. coli

One compound in the heat map (Fig. 2), MAC13772 (4) (Fig. 5a), was uniquely suppressed by biotin (Supplementary Fig. 18). The late steps of biotin synthesis are catalyzed by the enzymes BioF, BioA, BioD and BioB (Supplementary Fig. 19)44. Recently, the role BioC and BioH along with enzymes of fatty acid biosynthesis, in providing the intermediate pimeloyl-ACP for the assembly of the biotin ring, were elegantly demonstrated45.

Figure 5. MAC13772 is an inhibitor of biotin biosynthesis in E. coli.

(a) Chemical structure of MAC13772. (b) Dose-response curve of MAC13772 against recombinant BioA. The data represent the averages of 6 replicates ± s.d. and the dose response curve was fitted to the four parameter logistic nonlinear regression curve yielding an IC50 value of 250 ± 28 nM (See Online methods). (c) Spectral analysis of the BioA-MAC13772 interaction. BioA (5 μM) was titrated with up to 10 μM of MAC13772 and the UV-visible spectra of the mixture were recorded following each addition. The protein-ligand interaction is associated with a shift in the characteristic λmax of PLP bound to the active site Lys-274 residue from 420 nm characteristic of the internal aldimine to 393 nm representing the newly formed PLP-inhibitor adduct. The spectrum in red is of BioA prior to compound addition, in blue of the BioA-MAC13772 mixture at the highest compound concentration tested. Inset: Absorbance of the BioA-MAC13772 adduct at 393 nm vs. the molar ratio of [MAC13772]/[BioA]. Note the absorbance plateauing at a molar ratio of ~ 1 suggesting a 1:1 stoichiometric interaction between the inhibitor and the target. (d) Model for BioA-MAC13772 interaction. The primary amine of the hydrazine group in MAC13772 displaces the Schiff base between Lys-274 and PLP (internal aldimine) in the active site of BioA and reacts with the cofactor.

Given that E. coli cells are permeable to the late intermediates in biotin biosynthesis, we tested the suppression of the inhibitory activity of MAC13772 in the presence of 7-keto-8-aminopelargonate (KAPA), 7,8-diaminopelargonate (DAPA), dethiobiotin (DTB) in comparison to the unsupplemented and biotin controls. As summarized in Supplementary Table 4, inhibition by MAC13772 was fully reversed by DAPA, DTB and biotin, i.e. the products of the BioA, BioD and BioB reactions, respectively. In contrast, KAPA had no effect on MAC13372 activity. We thus reasoned that the step catalyzed by BioA was likely the target of this inhibitor. BioA, 7,8-diaminopelargonic acid synthase, is a PLP-containing transaminase that uses S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as an unusual amino donor to convert KAPA into DAPA46. We assayed the inhibitory activity of MAC13772 against recombinant E. coli BioA through a feeding assay of a bioA auxotroph (see Online methods). The dose-response curve in Fig. 5b shows that MAC13772 is a potent inhibitor of BioA with an IC50 of ~ 250 ± 28 nM.

We hypothesized that inhibition of BioA by MAC13772 is likely mediated through the interaction of the hydrazine moiety in the compound with PLP in the active site of the enzyme. To test this, we assessed the UV-visible spectra of BioA when titrated with the inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 5c, the interaction of MAC13772 with BioA is associated with a shift in the λmax of the internal aldimine of the PLP-bound enzyme from 420 nm to 393 nm representing the newly formed PLP-inhibitor adduct. The molar ratio plot of [MAC13772]/[BioA] (Fig. 5c-inset) indicates that the interaction between the protein and the ligand is stoichiometric. A model of the BioA-MAC13772 interaction is shown in Fig. 5d.

Having established the biochemical interaction of BioA with MAC13772, we were interested in exploring the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of this compound. We evaluated the antibacterial and biochemical activity of 24 analogs (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5). We began by evaluating changes of substituents on the benzyl ring in the parent molecule and their position relative to the thioacetohydrazine chain (analogs 5 through 13). All compounds in this category inhibited BioA, albeit with less potency. However, the different modifications had a more drastic effect on their antibacterial activity against E. coli. Specifically, the position of the nitro group on the benzyl ring greatly influences biological activity with the ortho- position being highly favored (analogs 5, 6 and 7). Alternatively, a chloro or a methyl substitution at the ortho-position on the benzyl ring do not gravely alter their antibacterial activity (analogs 9 and 12). The requirement of the hydrazine moiety for the activity of MAC13772 was tested by either protecting it with an acetyl group or by modifying it (analogs 14 through 18). Confirming our hypothesis, all analogs lacking the hydrazine group were completely inactive in both antibacterial and biochemical assays. Given this observation, the activity of the side chain of varying lengths without the benzyl ring was tested (analogs 19 through 23). The varying hydrazine-containing side chains only showed slight to moderate in vitro inhibition of BioA and no significant antibacterial activity. Interestingly, even in the case of the compounds 19 and 23 that had diminished antibacterial activity, growth inhibition was not suppressed in the presence of biotin. Replacing the benzyl ring in the parent compound with various rings was not tolerated especially with respect to antibacterial activity (analogs 24 through 28). This establishes the role of the benzyl ring for both the specificity and potency of MAC13772. Supplementary Fig. 20 summarizes our findings from the SAR investigation.

Table 1.

Structure-activity relationships of MAC13772 and analogs

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | MIC (μg/ml)a | % Inhibitionb | ||

|

| ||||||||

| −bio | +bio | 1 μM | 10 μM | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| MAC13772 | NHNH2 | NO2 | H | H | 8 | >256 | 100 | 100 |

| *Effect of Substitution on Benzene ring in Series a | ||||||||

| 5 | NHNH2 | H | NO2 | H | 256 | >256 | 42 | 84 |

| 6 | NHNH2 | H | H | NO2 | 64 | >256 | 66 | 100 |

| 7 | NHNH2 | H | H | H | 64 | >256 | 49 | 100 |

| 8 | NHNH2 | F | H | H | 32 | >256 | 36 | 100 |

| 9 | NHNH2 | Cl | H | H | 16 | >256 | 63 | 100 |

| 10 | NHNH2 | OH | H | H | 256 | 256 | 32 | 70 |

| 11 | NHNH2 | NH2 | H | H | 256 | >256 | 58 | 100 |

| 12 | NHNH2 | CH3 | H | H | 16 | >256 | 81 | 100 |

| 13 | NHNH2 | OCH3 | H | H | 128 | >256 | 65 | 100 |

|

| ||||||||

| *Effect of changing hydrazine functionality on R1 in Series a | ||||||||

| 14 | NHNHAc | H | H | NO2 | >256 | >256 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | CH2CH3 | NO2 | H | H | >256 | >256 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | NH2 | NO2 | H | H | >256 | >256 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | CH3 | NO2 | H | H | >256 | >256 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | OH | NO2 | H | H | >256 | >256 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| *Activity of the side chain of the parent molecule in Series b | ||||||||

| 19 | NH2 | CH2SCH3 | - | - | 64 | 64 | 50 | 64 |

| 20 | NH2 | CH2SH | - | - | 256 | 256 | 20 | 34 |

| 21 | NH2 | CH2CH2CH3 | - | - | >256 | >256 | 1 | 40 |

| 22 | NH2 | CH2CH3 | - | - | >256 | >256 | 0 | 8 |

| 23 | NH2 | CH3 | - | - | 128 | 128 | 7 | 19 |

|

| ||||||||

| *Effect of different ring substituents in R2 in Series bc | ||||||||

| 24 | NH2 | Benzothiophene | - | - | >256 | >256 | 15 | 69 |

| 25 | NH2 | CH2SCH2Ph | - | - | 64 | >256 | 60 | 100 |

| 26 | NH2 | CH2SNaph | - | - | >256 | >256 | 71 | 100 |

| 27 | NH2 | CH2SPyr | - | - | 64 | >256 | 32 | 77 |

| 28 | NH2 | Nitrobenzyl | - | - | >256 | >256 | 0 | 29 |

MICs are determined against E. coli MG1655 in absence and presence of 2 nM of biotin (see Online methods)

The biochemical activity of analogs is determined against recombinant E. coli BioA through a feeding assay of a bioA auxotroph at 1 and 10 μM and expressed as a % of the respective DMSO control (see Online methods)

Abbreviations:; Ph: phenyl; Naph: naphthalenyl; Pyr: pyridine

DISCUSSION

Characterizing the MOA of biologically active small molecules remains one of the biggest hurdles of whole-cell based screening in bacteria. In this work, we presented an approach that relies on metabolite suppression to explore the MOA of small molecules that target bacteria under nutrient-limited conditions. The metabolic suppression profiles of 22 known antibiotics revealed how this approach could provide information regarding the import, cellular target(s) and downstream effects of compounds that target bacterial physiology under nutrient restriction. Interestingly, we did not encounter suppression phenotypes that suggest off-target interactions. Furthermore, the consistency of the metabolic suppression profiles of known antibiotics with their well-characterized MOA suggests that this approach can provide a clear mechanistic fingerprint directly related to biological activity.

The metabolic suppression profile of MAC168425 illustrates the interrelationship between glycine and threonine metabolism. Our work strongly suggests that its inhibitory activity is mediated through the biosynthesis or utilization of glycine. Our observation that L-threonine doesn’t suppress the activity of MAC168425 in a Δtdh mutant as well as in a ΔltaE mutant is consistent with the fact that the Tdh-Kbl mediated threonine catabolic pathway plays a more significant role in replenishing the cellular pool of glycine40. The need for a triple deletion mutant (ΔltaEΔtdhΔkbl) to fully abolish antagonism by threonine may be due to it being non-specifically oxidized to α-amino-β-ketobutyrate at high concentrations in the (ΔltaEΔtdh) which would allow glycine formation to proceed through the major pathway. Processes involving glycine production and utilization are central to the biosynthesis of several essential cellular metabolites40. MAC168425 can provide a useful chemical probe to explore the interconnectivity of metabolic pathways centered on the transfer of one-carbon units.

The MOA of MAC173979 was of great interest to us because it displayed a characteristic fingerprint of inhibitors of PABA and folate metabolism but represented a previously unexplored chemical scaffold. Indeed, we have shown that MAC173979 is a time-dependent inhibitor of PABA synthesis in E. coli with a demonstrably slow off-rate. In this respect, the effectively irreversible inhibition by this compound should resist competition from the buildup of substrate arising from upstream reactions. Interestingly, an analog of MAC173979 lacking the Michael acceptor had a comparable activity to the parent molecule, suggesting a MOA other than Michael addition. To our knowledge, MAC173979 represents the first PABA biosynthesis inhibitor with activity against Gram-negative bacteria.

MAC13772 provides an example of a potent inhibitor that targets vitamin metabolism. Biotin biosynthesis is a promising target for antimicrobial development47 given that it is required by all forms of life but can only be synthesized by microorganisms and plants47,48. Furthermore, biotin levels in human serum are too low to provide adequate rescue to a pathogen impaired in biotin synthesis49. Our SAR investigation of 24 analogs of MAC13772 revealed the absolute requirement of the hydrazine group for activity. Hydrazine-containing molecules have found success in treating a variety of diseases (for examples see Ref.50). Many enzymes involved in biosynthetic pathways in E. coli are PLP-containing enzymes so we found particularly intriguing the strict dependence of MAC13772 activity on biotin restriction. In this respect, the specificity and potency of the inhibitor seems to highly depend on the presence of the benzene ring and the nature of any substituents on it. This suggests a potentially important role for the ring in the interaction with BioA.

Small molecules that target metabolic pathways in bacteria growing under nutrient limitation allows for the investigation of bacterial physiology under conditions far from the standard laboratory culturing environment. This increases the number of potential targets that can be explored for antimicrobial drug development. Exploiting the power of metabolic complementation can significantly speed up the characterization of the MOA of small molecules of interest. Indeed, inhibitors of bacterial biosynthetic capabilities could provide a much needed addition to the dwindling repertoire of effective antibiotics.

ONLINE METHODS

Reagents

Antibiotics were added to the media as needed with final concentrations as follows: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. For the primary screen, the library compounds were prepared to a final concentration of 250 μM in 25% DMSO. For follow up analysis, all compounds were solubilized in DMSO.

The ~ 30,000 small molecule library was purchased from Maybridge Ltd., Cornwall, UK; ChemBridge Corp., San Diego, CA, USA; Prestwick Chemical, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA; BIOMOL International, L.P., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA; Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd., Oakville, ON, Canada and MicroSource Discovery Systems Inc., Gaylordsville, CT, USA. The main compounds used in this study (MAC168425, MAC173979, MAC173979-D, MAC13772 and analogs 5 through 24) were purchased from their respective suppliers (listed in Supplementary Tables 3 and 5) and characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HR-MS (the chemical characterization data is in the Supplementary Note in Supplementary information). KAPA was supplied from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and DAPA from Caymen Chemicals. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma (Oakville, ON).

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

E. coli K-12 strains MG1655 and BW25113 were grown at 37°C with aeration at 250 rpm in liquid M9 minimal salts media 51 with 0.4% glucose as a carbon source and 20 mM ammonium chloride as a nitrogen source. For all cell-based assays, the bacterial culture was prepared as follows: a single colony of E. coli was grown overnight in M9 minimal media in a 37 °C incubator shaking at 250 rpm. The saturated overnight culture was diluted 1/50 in fresh M9 minimal media and grown in a 37 °C incubator shaking at 250 rpm until it reached an OD600 of ~0.4–0.5. The subculture was then diluted 103 and 104-fold into fresh media (minimal or supplemented, respectively) and set up to a final volume of 200 μl in clear flat bottom 96-well plates.

Primary screen in minimal media

The bacterial culture was prepared as described above. The clear flat bottom 96-well assay plates were set up with the library compounds in triplicate to a final concentration of 10 μM and with high and low controls of 0.2% DMSO and 10 μg/ml of norfloxacin, respectively. Controls constituted 20% of each assay plate. All the liquid handling was carried out using the Biomek FX liquid handler (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) The mid-log subculture was then diluted 103-fold into fresh M9 minimal media and set up in the assay plates using the μFill Microplate Dispenser (Biotek, Winooski, VT) to a final volume of 200 μl per well. Upon mixing of the bacterial culture with the screening compounds, the OD600 of the plates was read using the Envision (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The background reading is to account for any interference due to low compound solubility in the growth media or due to colored compounds. The plates were then incubated in a 37 °C stationary incubator for 12 hours before measuring their OD600. For a summary of the small molecule screening data see Supplementary Table 1.

Analysis of the primary screen data

The triplicate measurements were analyzed independently. Bacterial growth (G) was first calculated as follows

where OD600 (t=0) and OD600 (t=16) correspond to absorbance of the samples before and after incubation of the assay plates, respectively. Converting bacterial growth (G) to % residual growth (%G) is calculated as follows

where Gs is the bacterial growth in the presence of the tested compound, and μ+ and μ-are the averages of the high and low controls, respectively. For hit selection, the statistical cutoff for the primary screen was 80% residual growth (3 standard deviations below the high controls (100% residual growth)). Hence, compounds for which each of the triplicate measurements inhibited growth by at least 20% relative to the high controls was scored as a hit (an active) in the primary screen.

Dose-response determination of priority actives

The 11-point dose-response determinations were carried out in duplicate in two types of media: M9 minimal media and the same media supplemented with amino acids, vitamins and nucleobases (for recipe see Supplementary Table 2). The bacterial culture was prepared as described above. The subculture was then diluted 103 and 104-fold into fresh M9 minimal media and supplemented M9 minimal media, respectively and set up to a final volume of 200 μl in clear flat bottom 96-well plates containing half-log serial dilutions of each tested compound (1 nM– 80 μM) as well as high and low controls (0.2% DMSO and 10 μg/ml of norfloxacin, respectively). Upon mixing of the bacterial culture with the compounds, the OD600 of the plates was read using the Envision (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) to account for background absorbance. The plates were then incubated in a 37 °C stationary incubator for 16 hours before measuring their OD600.

Analysis of dose-response determinations

For each type of media, the duplicate EC50 measurements were analyzed independently. Percent residual growth (%G) was calculated as described above. %G was plotted against compound concentration on a semi-logarithmic plot and fit to the background corrected equation to determine EC50

where range is the difference between the maximum and minimum asymptotes of the curves at 0 and infinite [I], respectively,, [I] is the concentration of the tested compound (μM), S is the slope (or Hill) factor and EC50 is the compound concentration that inhibits growth by 50%.

Determinations of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Determinations of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were made for the compounds prioritized for follow up studies. All of these compounds were reordered from suppliers. The MIC values were determined in liquid M9 minimal media and minimal media supplemented with amino acids, vitamins and nucleobases (for media composition see Supplementary Table 2). The bacterial culture was prepared as described above. The diluted subculture in M9 minimal or supplemented minimal media was then set up to a final volume of 200 μl in clear flat bottom 96-well plates containing 2-fold serial dilutions of each tested compound (0.25– 250 μg/ml). After mixing of the bacterial culture with the compounds, the OD600 of the plates was read using the Envision (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) to account for background absorbance. The plates were then incubated in a 37 °C stationary incubator for 16 hours before measuring their OD600. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that inhibits visible growth.

Metabolic suppression profiling

The metabolic suppression array was prepared in the format shown in Fig. 3a and in Supplementary Fig. 4 as a 20× stock plate (for concentrations see Supplementary Table 2) to be used for metabolic suppression profiling. The bacterial culture was prepared as described above. The subculture was then diluted 103-fold into fresh M9 minimal media and set up to a final volume of 200 μl in clear flat bottom 96-well plates containing 4× the MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of each active and a 1/20 dilution of the metabolic suppression array stock plate. After mixing, the OD600 of the plates was read using the Envision (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) to account for background absorbance. The arrays were then incubated at 37 °C for 16 hours and their absorbance measured at 600 nm.

Analysis of metabolic suppression profiles

For each well in the metabolic suppression experiments, bacterial growth (G) was calculated as follows

where OD600 (t=0) and OD600 (t=16) correspond to absorbance of the plates before and after incubation, respectively. % residual growth (%G) was calculated as follows

where Gs is the bacterial growth in the presence of the tested metabolite(s), and GM9ALL and GM9 represent the bacterial growth in minimal and supplemented minimal media, respectively.

The metabolic suppression profiles of the 93 actives shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 were hierarchically clustered using the UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) clustering method52,53 and the resulting tree was visualized using the open source software FigTree.

Creation of double and triple deletion mutants in threonine catabolism

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from single deletion mutants in tdh, kbl and ltaE obtained from the Keio library15. Primers designed to amplify 500 bp upstream and downstream the deletion region in each deletion strain were as follows: for the Δtdh region: 5′-ATATTATCACCGGTACGCTTGG-3′ and 5′-ATTTGCCCGTTGCCACTTCAATCC-3′; for the ΔltaE region: 5′-AGGCGACAGAGCCAGAACGT-3′ and 5′-AGACCATATCGCGCATGACTTCG-3′ and for the Δkbl region: 5′-GAAAGAATTCTATAAATTAG-3′ and 5′-CCCACCAGATCAAACGACAG-3′. To create a tdh ltaE double deletion mutant, the FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette in Δtdh was eliminated using the FLP helper plasmid pCP20 as previously described54. About 2–4 μg of purified PCR product from the ΔltaE region was transformed into the resistance marker free Δtdh strain containing pKD46 and transformants were selected on LB agar medium with kanamycin (50 μg/ml)15. The kanamycin resistance cassette was then eliminated from the tdh ltaE double deletion mutant by the same method described above. To create a tdh ltaE kbl triple deletion mutant, about 2–4 μg of purified PCR product from the Δkbl region was transformed into the resistance marker free Δtdh ΔltaE strain containing pKD46 and transformants were selected on LB agar medium with kanamycin (50 μg/ml). All deletion mutants were verified by PCR to confirm that the genes of interest were deleted.

Cloning, expression and purification of recombinant PabA, PabB and PabC

To isolate PabA, PabB and PabC recombinant proteins, constructs were created to overexpress each protein with a N-terminal poly-histidine tag. Briefly, the genes encoding pabA, pabB and pabC were amplified from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA using Phusion polymerase (Fermentas) using the following primers: for pabA: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCGAAGGAGATACTAGCTAGATGATC CTGCTTATAGATAAC-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTCAGCGATGCAGGAAATTAGC-3′; for pabB: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCGAAGGAGATACTAGC TAGATGAAGACGTTATCTCCCGCT-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTG GGTCTTACTTCTCCAGTTGCTTCAG-3′; for pabC: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCGAAGGAGATACTAGCTAGATGTTCT TAATTAACGGTCAT-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCCTAATTCGGGCGCTCACAAAG-3′. The PCR products were purified and cloned into pDEST17 using the Gateway cloning and Expression Kit (Invitrogen, Canada) and the constructs confirmed by DNA sequence analysis (MOBIX, McMaster University). Each construct was transformed into E. coli BL21AI electrocompetent cells prior to protein expression and purification. The following procedure was followed for the expression and purification of each of the three proteins. For protein expression, each clone was grown in 2 L of LB with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C, shaking at 250 rpm until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.6. The culture was then induced with 0.2% L-arabinose and grown for an additional 3 hours prior to harvesting by centrifugation at 10,000 g. The cell pellets were resuspended and washed with a 0.85% saline solution, pelleted and stored at −20 °C. For protein purification, the cell pellets was thawed and resuspended in 25 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH= 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 2 mM BME, 0.5 mg DNase, 0.5 mg RNase, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). Cells were lysed by passage through a cell disrupter with continuous flow at 30,000 psi and clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 g for 1 hour. The clarified lysate was purified by nickel chelating chromatography using a 1 mL HiTrap affinity column (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, Canada). The column was washed with buffer A (50 mM Tris pH= 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 2 mM BME) and eluted with a linear gradient of 15–300 mM of imidazole. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those containing pure His-tagged protein were pooled and desalted through a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE) against the final storage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10% glycerol). The concentration of purified proteins was determined by the Bradford assay (BioRad). About 20 mg were obtained for each of the three enzymes. Fractions rich in pure protein were stored in aliquots at −80°C.

Pab enzyme assays

Enzyme assays were conducted in triplicate at room temperature with 25 nM of PabA and PabB, 50 nM of PabC, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 μM PLP, 1 mM L-glutamine, 40 μM chorismate and the indicated concentrations of MAC173979. The inhibition assays were initiated by addition of a mixture of the three enzymes and quenched with an equal volume of freshly prepared 8 M urea. The reaction progress curves were monitored every 10 minutes for 60 minutes and determined by a stopped HPLC-assay that allowed for the quantification of the conversion of chorismate to PABA. The two analytes were separated on a C18 reverse phase column (Nova-Pak C18, 4 μm, 3.9 x 150 mm, Waters) and eluted isocratically with 5% acetic acid in double distilled H2O55. The analytes were visualized by UV absorbance at 275 nm and identified by comparing their retention times and UV absorption spectra to authentic standards. The progress curves were plotted to the rate equation of slow-binding inhibition42,43.

using Sigma Plot 12.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), where v0 and vs are the initial and final steady-state reaction velocities, respectively, t is the time and kobs is the apparent first order rate constant for the interconversion between the initial and steady-state rates.

Expression and purification of recombinant BioA

To isolate recombinant BioA protein, the strain AG1-pCA24N-bioA (JW0757) from the ASKA library was used. The clone was grown in 2 L of LB with chloramphenicol (80 μg/ml) at 37 °C, shaking at 250 rpm until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.6. The culture was then induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and grown for an additional 3 hours prior to harvesting by centrifugation at 10,000 g. The cell pellet was resuspended and washed with a 0.85% saline solution, pelleted and stored at −20 °C. For protein purification, the cell pellet was thawed and resuspended in 25 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH= 8, 500 mM NaCl, 100 μM PLP, 50 mM imidazole, 0.5 mg DNase, 0.5 mg RNase, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). Cells were lysed by passage through a cell disrupter with continuous flow at 30,000 psi and clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 g for 1 hour. The clarified lysate was purified by nickel chelating chromatography using a 1 mL HiTrap affinity column (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, Canada). The column was washed with buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH= 8, 500 mM NaCl, 100 μM PLP, 50 mM imidazole) and eluted with a linear gradient of 50–400 mM of imidazole. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those containing pure His-tagged protein were pooled and desalted through a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE) against the final storage buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 10% glycerol). The concentration of purified proteins was determined by the Bradford assay (BioRad). The BioA yield was about 30 mg from cell pellets from 2 L of culture. Fractions rich in pure protein were stored in aliquots at −80 °C.

BioA assay

For the determination of the IC50 of MAC13772, the BioA enzyme assay was conducted in triplicate at room temperature with 100 nM of BioA, 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5), 15 μM of KAPA, 1 mM of SAM and 1–10000 nM of MAC173979 (the half-log serial dilutions of inhibitor stocks were made in 25% DMSO to reduce the final DMSO concentration in the assay to 0.5%). The 100 μL reactions were initiated by addition of the enzyme and quenched after 20 minutes with 10 μL of 100% trichloroacetic acid. DAPA production was biologically determined based on a strategy originally described for biotin56. The plates were prepared as previously described45. A 5 mL culture of E. coli BW25113 ΔbioA (from the Keio library) was grown overnight in M9 minimal media supplemented with 2 nM biotin. Cells from the saturated culture were pelleted and washed in fresh minimal media (without biotin) and pelleted again. The pellet was resuspended in 25 mL of fresh minimal media (without biotin). The subculture was grown at 37 °C, 250 rpm for 4–5 hours to deplete biotin. Cells are then pelleted and washed again in 10 mL of minimal media. Cells were mixed to a final OD600 of 0.1 into 50 mL of M9 minimal agar (1.5%) containing 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride to a final concentration of 0.1% w/v. The mixture (16 mL) was poured into single well plates (Nunc OmniTray, 128 mm × 86 mm). To evaluate BioA activity, 10 μl of each reaction was spotted on a 6 mm disc (BBL) placed on the agar plates. Plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C and growth zones appeared as a deep pink formazan deposit. The plates were scanned using an Epson Perfection v750 and the radii of growth were measured using Fiji57 with a scale of 22 pixels/mm. The amount of DAPA formed from the reactions was estimated based on a DAPA standard curve (5–600 pmol) where growth was linear with the logarithmic amount of DAPA spotted. The DAPA standard curve was conducted with every experiment.

For each inhibitor concentration, the amount of DAPA formed (pmol) was expressed as a percentage of the DMSO control and the dose-response curve was plotted to the four parameter logistic nonlinear regression model.

using Sigma Plot 12.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), where min is the minimum asymptote at infinite [I], max is the maximum asymptote in the absence of the inhibitor, [I] is the concentration of the tested compound (nM), Hill factor is the slope (steepness) of the curve and IC50 is the compound concentration that inhibits enzyme activity by 50%. For the evaluation of the activity of the different MAC13772 analogs, the reactions were set up in duplicate as described above in the presence of each inhibitor at 1 and 10 μM (at a final DMSO concentration of 0.25% and 2.5%, respectively). For each analog, the amount of DAPA formed was expressed as a percentage of the respective DMSO control (% Activity) and the % Inhibition was calculated as (100 – % Activity).

Spectral analysis of BioA-MAC13772 interaction

A 1 mL mixture of 5 μM of BioA in 50 mM of HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) was titrated with up to 10 μM of MAC13772. The titration was monitored by measuring the UV-visible spectra (from 300–500 nm) in a 1 mL quartz cuvette after each addition of the inhibitor using Varian Cary Bio 300 UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Wanner of Purdue University and Hirotada Mori of the Nara Institute for providing the Keio library clones used in these studies, Fazmin Nizam for developing and assisting in using the in-house web-based UPGMA-based cluster analysis tool, Mehdi Keramane for NMR characterization of analogs used in this study and Alfredo Capretta for inspiring discussions. We also thank Jan Blanchard and Cecilia Murphy for technical support during the primary screen. This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-81330) and by a Canada Research Chair award to E.D.B. S.Z. was supported by the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.Z. designed and performed all experiments and co-wrote the manuscript. L.F.F. purified recombinant BioA and optimized cell-based and biochemical assays for the study of MAC13772 under the guidance of S.Z.. E.D.B. conceived of and oversaw the project and co-wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Brown ED. Is the GAIN Act a turning point in new antibiotic discovery? Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2013;59:153–156. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haselbeck R, et al. Comprehensive essential gene identification as a platform for novel anti-infective drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1155–72. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher H, et al. 10 x ‘20 Progress--Development of New Drugs Active Against Gram-Negative Bacilli: An Update From the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56:1685–1694. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdine L, Kodadek T. Target identification in chemical genetics: the (often) missing link. Chemistry & biology. 2004;11:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons AB, et al. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:62–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giaever G, et al. Chemogenomic profiling: identifying the functional interactions of small molecules in yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:793–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307490100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoon S, et al. An integrated platform of genomic assays reveals small-molecule bioactivities. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:498–1004. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lum PY, et al. Discovering modes of action for therapeutic compounds using a genome-wide screen of yeast heterozygotes. Cell. 2004;116:121–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, et al. Multicopy suppressors for novel antibacterial compounds reveal targets and drug efflux susceptibility. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathania R, et al. Chemical genomics in Escherichia coli identifies an inhibitor of bacterial lipoprotein targeting. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:849–56. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua Q, Yang C, Oshima T, Mori H, Shimizu K. Analysis of gene expression in Escherichia coli in response to changes of growth-limiting nutrient in chemostat cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2354–66. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2354-2366.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao H, Bausch C, Richmond C, Blattner FR, Conway T. Functional genomics: expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6425–40. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6425-6440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaslaver A, et al. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat Methods. 2006;3:623–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba T, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006 0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamberlain LM, Strugnell R, Dougan G, Hormaeche CE, Demarco de Hormaeche R. Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain MS11 harbouring a mutation in gene aroA is attenuated and immunogenic. Microb Pathog. 1993;15:51–63. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuccui J, et al. Development of signature-tagged mutagenesis in Burkholderia pseudomallei to identify genes important in survival and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1186–95. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01240-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei J, Nourbakhsh F, Ford C, Holden D. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes in a murine model of bacteraemia using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Molecular microbiology. 1997;26:399–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5911966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polissi A, et al. Large-scale identification of virulence genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infection and immunity. 1998;66:5620–5629. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5620-5629.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samant S, et al. Nucleotide biosynthesis is critical for growth of bacteria in human blood. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cersini A, Salvia AM, Bernardini ML. Intracellular multiplication and virulence of Shigella flexneri auxotrophic mutants. Infect Immun. 1998;66:549–57. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.549-557.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho J, Juurlink D. Considerations when prescribing trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal. 2011;183:1851–1859. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittard J, Yang J. In: Escherichia Coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Böck A, et al., editors. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:330–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handschumacher RE. Orotidylic acid decarboxylase: inhibition studies with azauridine 5′-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:2917–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobb J, Pearcy S, Gholson R. Metabolism of 6-aminonicotinic acid in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 1977;131:789–794. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.3.789-794.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richmond M. The effect of amino acid analogues on growth and protein synthesis in microorganisms. Bacteriological reviews. 1962;26:398–420. doi: 10.1128/br.26.4.398-420.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eidinoff ML, Knoll JE, Marano B, Cheong L. Pyrimidine studies I. Effect of DON (6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine) on incorporation of precursors into nucleic acid pyrimidines. Cancer Research. 1958;18:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levenberg B, Melnick I, Buchanan J. Biosynthesis of the purines. XV. The effect of aza-L-serine and 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine on inosinic acid biosynthesis de novo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1957;225:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahluwalia G, Grem J, Hao Z, Cooney D. Metabolism and action of amino acid analog anti-cancer agents. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1990;46:243–271. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90094-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wargel RJ, Shadur CA, Neuhaus FC. Mechanism of D-cycloserine action: transport systems for D-alanine, D-cycloserine, L-alanine, and glycine. J Bacteriol. 1970;103:778–88. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.3.778-788.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zawadzke LE, Bugg TD, Walsh CT. Existence of two D-alanine:D-alanine ligases in Escherichia coli: cloning and sequencing of the ddlA gene and purification and characterization of the DdlA and DdlB enzymes. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1673–82. doi: 10.1021/bi00220a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuhaus FC, Lynch JL. The Enzymatic Synthesis of D-Alanyl-D-Alanine. 3. On the Inhibition of D-Alanyl-D-Alanine Synthetase by the Antibiotic D-Cycloserine. Biochemistry. 1964;3:471–80. doi: 10.1021/bi00892a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strominger JL, Ito E, Threnn RH. Competitive inhibition of enzymatic reactions by oxamycin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1960;82:998–999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stokstad EL, Jukes TH. Sulfonamides and folic acid antagonists: a historical review. J Nutr. 1987;117:1335–41. doi: 10.1093/jn/117.7.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green JM, Nichols BP, Matthews RG. In: Escherichia Coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Neidhardt FC, et al., editors. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 665–673. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh C. Antibiotics: Actions, Origins, Resistance. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer RS, Berry A, Gaines CG, Jensen RA. Comparative Action of Glyphosate as a Trigger of Energy Drain in Eubacteria. Journal of Bacteriology. 1986;168:1147–1154. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1147-1154.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stauffer GV. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Böck A, et al., editors. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris JG. Utilization of L-threnonine by a pseudomonad: a catabolic role for L-threonine aldolase. Biochem J. 1969;115:603–5. doi: 10.1042/bj1150603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Copeland RA. Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis. Wiley; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cronan JE. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Böck A, et al., editors. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin S, Hanson RE, Cronan JE. Biotin synthesis begins by hijacking the fatty acid synthetic pathway. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:682–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoner GL, Eisenberg MA. Biosynthesis of 7, 8-diaminopelargonic acid from 7-keto-8-aminopelargonic acid and S-adenosyl-L-methionine. The kinetics of the reaction. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4037–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro S. Speculative strategies for new antibacterials: all roads should not lead to Rome. The Journal of antibiotics. 2013;66:371–386. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider G, Lindqvist Y. Structural enzymology of biotin biosynthesis. FEBS letters. 2001;495:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woong Park S, et al. Evaluating the sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to biotin deprivation using regulated gene expression. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lightcap E, Silverman R. Slow-binding inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase by hydrazine analogues. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 1996;39:686–694. doi: 10.1021/jm950437v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical Taxonomy: The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. W. H. Freeman; San Francisco: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romesburg C. Cluster Analysis For Researchers. Lulu Press; Morrisville, N.C: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baba T, Mori H. The construction of systematic in-frame, single-gene knockout mutant collection in Escherichia coli K-12. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;416:171–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-321-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walsh C, Erion M, Walts A, Delany J, Berchtold G. Chorismate aminations: partial purification of Escherichia coli PABA synthase and mechanistic comparison with anthranilate synthase. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4734–4779. doi: 10.1021/bi00389a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Genghof DS, Partridge CW, Carpenter FH. An agar plate assay for biotin. Arch Biochem. 1948;17:413–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.