Abstract

Purpose

The study uses qualitative research to gain a better understanding of what occurs after low-income women receive an abnormal breast screening and the factors that influence their decisions and behavior. A heuristic model is presented for understanding this complexity.

Design

Qualitative research methods used to elicited social and cultural themes related to breast cancer screening follow-up.

Setting

Individual telephone interviews were conducted with 16 women with confirmed breast anomaly.

Participants

Low-income women screened through a national breast cancer early detection program.

Method

Grounded theory using selective coding was employed to elicit factors that influenced the understanding and follow-up of an abnormal breast screening result. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and uploaded into NVivo 8, a qualitative management and analysis software package.

Results

For women (16, or 72% of case management referrals) below 250% of the poverty level, the impact of social and economic inequities creates a psychosocial context underlined by structural and cultural barriers to treatment that forecasts the mechanism that generates differences in health outcomes. The absence of insurance due to underemployment and unemployment and inadequate public infrastructure intensified emotional stress impacting participants’ health decisions.

Conclusion

The findings that emerged offer explanations of how consistent patterns of social injustice impact treatment decisions in a high-risk vulnerable population that have implications for health promotion research and systems-level program improvement and development.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, African-American, Health Care–Seeking Behavior, Social Inequity, Prevention Research

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer survival rate in the United States has increased since 1990.1 This increase has been attributed to earlier detection with the use of mammography, high-quality care, and effective adjuvant treatments.2,3 Despite overall lower mortality and higher survival rates, improvements in access and equity in mammography screening have not translated into survival improvements for disadvantaged women.4,5 Data indicate there is still inequality between breast cancer survival rates of white and high-income women compared to racial/ethnic minorities and women with low income.6–8 Women who are racial/ethnic minorities, live in rural areas, and/or have a low socioeconomic status (SES) tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at later stages and have lower survival and higher mortality rates.6,9,10 The inequality in survival may be partially explained by lower rates of follow-up, because as a group, racial/ethnic minority women and women with a low SES have lower rates of follow-up of abnormal breast screening results than white women and women with a high SES.5,10,11

The potential reduction in morbidity and mortality through breast cancer screening will never be realized without timely and efficient follow-up care once an abnormality has been detected.12 Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer are complex processes. Studies have established that minority and low-income women face many potential barriers in the social environment, which lead to lower rates of health care utilization, including follow-up of abnormal breast screening results.11,13–16 Barriers to obtaining timely diagnostic and treatment services include financial barriers, lack of continuity of medical care and social support, mistrust, communication difficulties, cultural factors, health beliefs, and other economic, personal, and family health priorities.17,18

Research suggests that social injustice—patterns of systematic disadvantage that undermine individual wellbeing such that people’s health prospects are limited by life choices not even remotely like those of others—can result in lack of access to health care, low-quality treatment, and subsequent cancer disparities.19–21 Studies indicate that the public health problem of inequitable health outcomes for women with breast anomalies not only is the result of an unjust basic structure of society but can also be addressed from a social justice perspective, which requires that researchers understand the psychosocial context within which consumers of health services operate.22–24

Cognitive representations of illness are internalized knowledge structures built by perceptions that subsequently guide behavioral responses and adaptive outcomes. Research in this area indicates that individuals develop mental models as a result of person-environment experiences that help them make sense of illness threats.25,26 The representation of disease is thus different for women confronted with social patterns of systematic disadvantage such as poverty, substandard housing, poor education, and lack of transportation.21–23,27 Because health-seeking behavior is precipitated by an assessment of one’s disadvantaged status, the identification of modifiable psychosocial determinants and the mechanisms that explain inequities in follow-up of abnormal breast screening results among low-SES women is critically important and could aid in the development of interventions.24

Understanding breast cancer cognitive representation and the emotional responses evoked offers a more precise explication of the psychosocial context within which health disparities occur. When a woman receives a breast cancer diagnosis, she learns for the first time of a health-threatening disease. Self-regulatory theory purports that information about a health threat activates previously described cognitive representations of the disease in order to cope.28,29 Cognitive representations utilized in the development of emotional responses to illness are comprised of five main dimensions: identity (interpretation of the symptoms associated with the illness and of labels attached to the illness), cause (likely causes of the illness, which may relate to the person’s beliefs about personal risk), timeline (the likely duration of the illness/how long will it last), consequences (the perceived severity of the illness and the potential impact on physical, psychological, and social functioning), and cure/control (the extent to which the illness can be successfully controlled or cured). This cognitive representation, defined by the social environment, is in turn proposed to activate coping responses designed to modify or deal with the threat to self and personal well-being.

Using the cognitive illness representation dimensions as a broad guide, this exploratory study investigated what occurs after low-income women receive an abnormal breast screening and the factors that influence their decisions and behavior. Enhanced understanding of determinants will lead to the development of public health interventions that take into consideration the outcomes of health inequities that may undermine follow-up. Lastly, definition of these factors enables an appreciation of the beliefs that promote healthy behaviors by women seeking breast-health care.

METHODS

Design

The data analyzed for this study were derived from in-depth telephone interviews of women participating in the Best Chance Network using an open-ended discussion guide. The study protocol was reviewed and received approval from the Department of Health and Environmental Control and the University of South Carolina institutional review boards (IRBs).

Participants and Recruitment

To understand the role of social injustice in this population we studied women who were screened through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), which provides free screenings and treatment to uninsured and underinsured women at or below 250% of federal poverty level, ages 40 to 64 for breast screening, and abnormal mammograms.30,31 A cross-sectional qualitative telephone design was used in this study. After IRB approval was received, newly screened women referred to the case management program during the quarter of January to April 2010 were recruited to participate in the “Understanding Breast Cancer” study. Case managers, whose role it is to ensure women with an abnormal screening result or a diagnosis of cancer receive timely and appropriate rescreening and diagnostic treatment services, were given recruitment flyers and information letters and asked to introduce the study to their eligible referrals. Women were considered eligible for the study if they had an abnormal mammogram requiring follow-up, were a new referral, and submitted a signed consent form. If women were immediately interested in participating in the study, case managers reviewed the study’s consent form with their client and the women submitted their signed consent to the case managers. If the women required additional time to consider participating in the study, they were allowed to mail their consent form to the investigators.

Measurement

Research staff were trained to conduct semistructured interviews with the participants. Women who consented and completed the interview were given a $20 gift card. Although the self-regulatory theory, per se, was not being tested, the five dimensions of the theory were intuitively used to broadly guide the development of the semi-structured interview guide questions. Questions designed to elicit the women’s stories included (1) perception of the impact of the diagnosis (What did you think about when you first received your results? How did you react? What do you think caused it? What do you stand to gain or lose?); (2) communication (Who talked with you about your results? How did you share the information with loved ones? What did you say?); and (3) behavioral intent to continue treatment (If a follow-up or 6-month mammogram is recommended by the doctor, do you plan to follow up? What has made it difficult to get your treatment and follow-up procedures? Do you think you will complete full treatment?). The semistructured format allowed participants to respond freely and answer questions in an open-ended way, and probes allowed the participants to drive the conversation. Each interview lasted 45 to 60 minutes. Participants were inherently homogenous because of their NBCCEDP eligibility, which requires being uninsured/underinsured, living at or below 250% of the federal poverty level, and being between the ages of 40 and 64. Demographic data collected included zip code and education level.

Data Analysis

Telephone interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and uploaded into NVivo 8, a qualitative management and analysis software package.32 One investigator and a research team member independently read and coded the transcripts according to operational definitions of each code. A coding workbook was iteratively developed using a grounded-theory approach; this method of qualitative data analysis derives a conceptual framework or theory from the data.33–35 The team discussed and agreed upon major themes with corresponding subthemes. Coding patterns were also compared to ensure adequate intercoder agreement. When consensus was not met a second investigator helped resolve discrepancies at regular coding meetings.36

We analyzed anonymized transcripts, and NVivo 8 was used to generate reports from the coded transcripts for each domain and derived subthemes. We applied selective coding procedures35 to these reports in order to identify the linkages between the primary domains and constructed a heuristic conceptual framework to elucidate the relationships between the domains and factors’ influencing the women’s decision processing. Finally, we compiled quotations from all participants and developed pertinent concepts and relationships. Because a grounded theory approach was used, data collection ended when repetitiveness that suggested data saturation was observed.

RESULTS

There were 82 women with abnormal breast results referred for case management during the study period. Based on study criteria, case managers discussed the study with 24 of these women, and 16, representing both rural (50%) and urban (50%) communities, consented to participate. One key reason for some declining to participate was because extended family members were not interested in the woman participating. Other women did not return the consent form for reasons unknown. Participants included 11 African-Americans, 4 whites, and 1 Latina. Average age of the women was 53 years. Participants’ average family size was two; 50% had less than high school (H/S) education, 44% H/S, and 6% some college degree. Ten women had a confirmed breast cancer diagnosis and six had abnormal screening results that required follow-up. Interviews were conducted on average 4 weeks after the participants received their breast screening results.

Findings

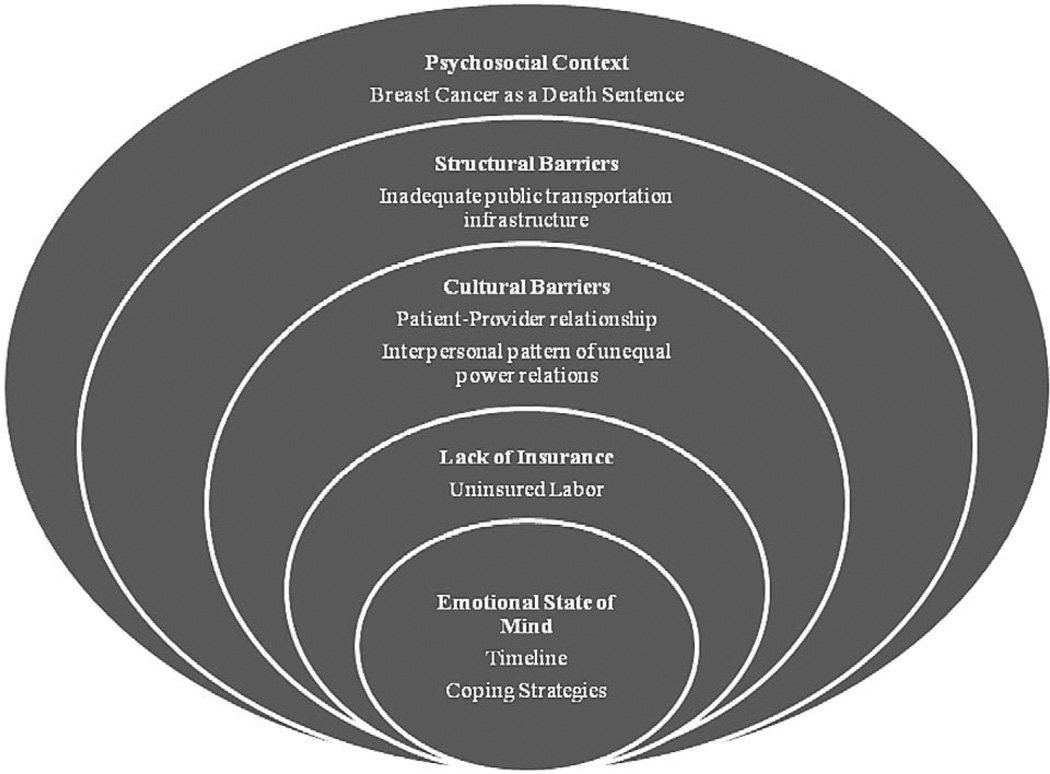

The data revealed multiple interrelated themes (Figure) influential to the treatment continuum after an abnormal breast finding. The themes demonstrated factors related as well as unrelated to social patterns of systemic discrimination that drive emotional responses. Themes included (1) psychosocial context, (2) structural barriers, (3) cultural barriers, (4) lack of insurance, and (5) emotional state relative but not limited to the barriers faced. The major themes and associated representative quotes elicited from the stories of the women are presented below.

Figure.

Heuristic Conceptual Framework: Factors Influencing Women’s Cognitive Processing of Breast Abnormality

Psychosocial Context

Psychosocial context—the constellation of cognitions and emotions experienced by the women toward their diagnosis, incorporating hopes, fears, and experience evaluations—is represented by the outermost circle in the Figure. The psychosocial context encompasses the women’s observance of higher cancer mortality rates among close family and friends, uninsured labor, and poverty status of the participants. Most women expressed tangible amounts of psychological stress associated with the high breast cancer mortality among close family and friends and their low SES. This theme, by definition, captures the essence of the self-regulatory dimensions and configures it into this major tenet in the women’s cognitive illness representation that is used to matter-of-factly determine treatment approach.

Consequently, after learning of their abnormal breast results, the women’s treatment decision making was influenced by factors predicated by their social environment and current economic status. Also demonstrated were the women’s awareness of their susceptibility to breast cancer and knowledge of treatment options and approaches. Decisions about the course of their treatment, however, were dictated by experiential knowledge gained from their social environment and included perceptions of unequal treatment due to poverty status.

Women in the study reported already making radical decisions about the treatment course, such as opting for mastectomies rather than lumpectomies, without sustained and reciprocal patient-provider dialogue. Experiential knowledge due to the number of breast cancer–related deaths in one’s family and community, as well as a labeled perception that women from vulnerable communities would not necessarily receive accurate or accessible information from a medical provider, exacerbated the belief that breast cancer is a “death sentence.” The quotes below exemplify this adamant treatment approach, i.e., when a less invasive procedure had the potential to save the breast but was declined in preference for more aggressive care as motivated by experiences with family and others in their social networks who had suffered from the disease, disease management costs, and personal fear of adverse outcomes. Mastectomies were discussed by all the women in the study as the treatment option most likely to succeed, even in the absence of medical provider recommendations to that effect.

“I could have the lump removed or I could have the breast removed. Within five minutes…I had decided that whatever it was I would rather just have the breast removed because I didn’t want to have to go back through this repeatedly.”

“Well, my first reaction when he told me, was to cut the whole breast off…that was my first thought… just go ahead and cut it. But then he said he didn’t thought it was that bad that I might, could save the breast, cause he said there’s a possibility that he could’ve saved the breast that I didn’t have to do the whole thing. But, I said, no, no we just gonna remove the breast.”

“It was phase II cancer, breast cancer and I could have gone with the lumpectomy…I had time to come home and think and talk about it, and when I went back I told him no, I wanted to take, just take it [breast] off.”

Structural Barriers

Our findings offer a rich description of barriers to screening and treatment decisions faced by vulnerable women represented in the sample. The women described their perception of a two-tiered pattern of injustice. First, women felt their “kind” were challenged by the economics of health care, whereby they felt exiled from guaranteed access to medical treatment when ill, including basic diagnostic information about their breast health status: “I just needed somebody to give me some information as to what is going on with me. They may not have to tell me what, if it’s cancer or not…but I went to the doctor and she couldn’t tell me nothing… I don’t know if that’s policy or not.”

Second, stories further illustrated the effects of how inadequate public transportation infrastructure ruthlessly challenged their efforts to secure health services.

“I just wrecked my car and I didn’t have any transportation. I had to go to my mother and ask her to take me…it was sort of hard just trying to get there, period…when you get there, you got to do a lot of waiting; and when you wait, you get hungry; unless you got money to go buy lunch, you see what I’m saying?”

“I think one of the problems is transportation. My sister, for instance, she heard that she might have breast cancer and she was having a time trying to get to that doctor. The only one that could help her get back and forth to the doctor was my mother [but] she didn’t have no gas money or anything. My mama had to pull up her pocket and my daddy and put gas in the car and take her down.”

“Is there no way that a van or something could pick [women] up-that needs cancer treatment or whatever…We have a lot of rural areas and there’s also a lot of low income.”

Cultural Barriers

The data revealed beliefs and perceptions of a woman’s social place played in understanding their diagnosis and treatment determination. For many of the women the consensus was,

“I would be obedient and do what I have to do to let the medical people do their part.”

Many of the participants found encounters with health care providers along the screening-treatment continuum frustrating, disempowering experiences. In addition, participants reported that many providers lacked good bedside manners. Poor patient-provider communication and patterns of unequal interpersonal power relations between patient and provider contributed to an interpersonal pattern of silence and frustration and impeded treatment adherence and potential follow-through on future appointments.

“If, the doctors or whatever, the nurses, if they would just allow the person to talk more…Yeah, allow the person to explain or to ask questions…instead of feeling that you’re, okay you’ve only got about 15 minutes or you’ve got 10 minutes…allow the person to express theyself more.”

“I went to have my incision looked at. And I said, “So what is it?” He ran off these words that didn’t mean bullshit to me. He didn’t say it was fatty tissue. He didn’t say anything. Just these off the wall words…of course I didn’t understand.”

“I had so many questions and believe me I was all for asking, but when four or five people came in, everything I had thought I would’ve asked I didn’t feel like asking again cause like I’m just like the average person now I guess…I wanted them to do it and then go about their business.”

The psychosocial hazard is that the participants perceived their appropriate role as the compliant or “good patient”—the representation of illness they constructed was based on their reality, a reality wherein a woman’s social role called on her to be in passive receipt of medical knowledge rather than an active participant. This pattern of communication was one in which some women reported themselves as playing the good patient who is silent, and the doctors presented themselves as too busy or unable to answer their questions in a clear and thorough manner. Often the women reported leaving the office frustrated and demoralized only to seek explanation for their medical results from other sources or to suffer in silence.

“In the first place I believe in my doctor so, I didn’t question what he said.”

Lack of Insurance

Having the “right” insurance was a major area of discussion by the women, in which they discussed increased risk for the disease to return. One woman said she didn’t have too many care options because “[doctors] don’t want to see you if you don’t have certain kind of insurance.”

The women discussed the impact of having no insurance because of underemployment and unemployment. Seasonal and undocumented labor were major factors influencing current decision for the type of treatment chosen in the case of a confirmed cancer diagnosis. Once again, decisions were made from a reality-based assessment of their disadvantaged status. The following quotes captures the frustration felt by many of the women who required a diagnostic mammogram for follow-up but were unable to see a provider because of lack of insurance.

“It’s frustrating to know that you don’t have insurance and it’s bad enough that you sick…and nobody will look at you because you ain’t got no insurance. I went through that so many times, got turned away so many times. The doctor gave me an appointment and as soon as they saw I had no insurance, they turn me away. I’m sorry, we can’t help you. When you get some insurance or when you get the money, then we can help you.”

“Ain’t no way that I [can] afford to have all those tests and stuff done…-because it would [be] too expensive.”

Emotional State of Mind

The emotional state, innermost circle of the Figure, defines the immediate reaction of the women once learning of the breast abnormality. Many had the reaction summarized in this quote: “death, first thing was death, oh God I’m gonna die. They got to plan a funeral.” This emotional reaction was conjured because of the representation assigned to breast cancer based on what was seen and dealt with in their environment. In turn, intrapersonal cognitive factors such as attitude to the illness and ultimately their coping style strategies were determined.

Timeline

A prominent feature of the illness representation was the potential chronicity of breast cancer. The women discussed “that it would always come back.” Accordingly, it was their ambition to manage the cancer as an acute illness rather than a cyclical or chronic disease by getting rid of the breast; one woman said, “I want to live as normal as I can get it…and if a breast is not serving [any] purpose, as far as in my body, I don’t need it…that’s how I feel.” Discussions encompassing diagnostic screening, remission, annual follow-ups, and the ever-present thought of potential new cancer growth were echoed with an attitude that was more about bringing individual risk exposure to a close. This was further driven by the fact that under the NBCCEDP the women became eligible for public insurance and so, largely, women discussed wanting to condense treatment into the shortest possible temporal space, in part to maximize the chances of securing all requisite health services while insured, and in part because of the need to end the emotional and psychological burden of the disease on self and loved ones.

“I feel like when you do a lumpectomy in so many years they’re gonna say it came back, and that’s why I chose to do that the mastectomy.”

“I just thought about asking the Lord who would be looking after my kids and how would things be done for them?”

Additionally, attitudes, although reportedly hopeful, were also filled with fear and sometimes anger and worry that they were being punished for something in their past.

“A lot of things went through my head, my lifestyle made me think I was doing wrong…you think about all sorts of things you’ve done in the past that might be part of it [cancer] … wrong things, wrong choices.”

Coping

Although some of the women discussed the persistent fear of cancer as a death sentence, none demonstrated any amount of cancer fatalism. Instead, the women discussed wanting to live for their children and grandchildren and a willingness to do everything to make sure that the cancer was treated. Several participants reported that sharing their results with family members, friends, or fellow “prayer warriors” resulted in a heightened sense of self-worth and a sense of their importance in the lives of others. Yet, equally crucial to how they dealt with the day-to-day disease management was their internal dialogue of self-assurance. In addition, they reported feeling grateful in having caught the cancer early and having the health care assistance to help them through the treatment continuum.

“One of the things that I didn’t want to do is just drown in self pity, I had to hurry up and maybe that first week when I talked with the doctor, I was feeling myself getting depressed and I’m like wait a minute, ‘No. Cancer don’t mean that I’m absolutely gonna die.’ So I had to come to terms with getting myself together and that’s what I did.”

“Well, you know your feeling comes from yourself, as an individual. It’s all how you take it…if you take it as it comes, and try to fight through that, your healing can be faster, so that’s what I’m trying to do…not give up hope…try to fight through it.”

The women went as far as to discuss a benefit in getting cancer: eligibility for public insurance would allow access to treatment for other chronic health conditions such as diabetes.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore what occurs after low-income women receive an abnormal breast screening and the factors that influence their decisions and behavior. The heuristic model delineates a representative pattern of the extent to which the factors in the results impacted the women’s behavior. Our finding espouses the complexity of care within this high-risk vulnerable population and evokes the need for examination of the relationship between the women’s emotional state of mind, the structural environment within which they live, and both real and perceived messages that they receive from their social environment in terms of someone deserving and receiving equal care. These elements, which influence the women’s cognitive representation once a diagnosis is received, are worth discussing in the context of health inequities and social injustice and to further understand the import of the heuristic model in guiding future studies.

Health inequities, differences in the major social determinants of health between groups with different social advantage/disadvantage, or the feeling among the women in the study that they would not receive treatment that was equal to their more financially stable counterparts, is rooted in a history of unequal economic and social conditions. The result, as reflected in these findings, is a psychosocial context wherein the women encountered barriers, real and perceived, to treatment such as low SES, individual characteristics, and treatment disparities requiring immense emotional and psychological energy to overcome. These findings are in agreement with studies that attribute disparities in breast cancer mortality to psychosocial factors.7,10,37 Inasmuch as breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death and the most recurrent form of cancer among women in the United States, public health researchers must attend to the psychosocial context within which the disease occurs, including the segmented labor market that creates a class of chronically unemployed and underemployed workers without access to medical insurance and, consequently, health services.11,14,38–40

Similar to existing literature examining the cognitive coping of patients with breast cancer, this study demonstrated that the participants’ beliefs about the identity of the disease, its consequences, and treatment options influenced and informed decisions.41–43 In one study, negative coping strategies were connected to social and demographic concomitants such as unemployment and low education.41 The absence of health insurance, high cancer mortality, and unequal cancer burden in their communities induced emotional responses of fear, despair, and hopelessness, alongside faith in themselves and their social networks. However, the more negative emotions during the time in which the women were required to make this rapid and potentially life-altering decision regarding treatment could explain why some of the participants chose a more radical treatment option. The experienced and perceived factors of social inequity largely dictated how the women interpreted challenges and ultimately their treatment choices, which often were not what the provider recommended.

Ambivalence about the beneficence of the medical establishment also figured into the decisions about treatment, though the prevailing sentiment was acquiescence to provider recommendations. Studies have shown that communication styles and preferences differ among minorities, limited–English proficiency, and disadvantaged populations as communication styles and preferences differ culturally and linguistically.44–47 Provider communication challenges experienced by participants in our study mediated health-seeking behavior, and are especially important to consider because provider communication is an integral component of patient-centered aspects of care delivery and thus determines care continuation. The acquiescent attitude reported by some of the women is a social role cultured by historical marginalization that robbed the women of their opportunity to ask questions and receive validation. This finding is similar to findings of breast cancer screening and survival studies with multiethnic women.48,49 Study findings present important implications for medically underserved populations and their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their health care. Beneath the surface of the women’s responses was dissatisfaction with the way they were treated. Providers should be vigilant to identify and resolve aspects of care with which patients are dissatisfied. Patient satisfaction is associated with aftercare, health outcomes, and participatory and team-based approaches to care, as well as perceptions of partnership with their providers.50

From a social justice perspective, inequities in breast cancer mortality and health disparities are problems that can be redressed by public health programs aimed at empowering vulnerable communities.51 Participants’ psychosocial histories, the structural and cultural treatment barriers they face, and their emotional states of mind with regard to these conditions suggest an explanation for continued disparities in breast cancer mortality. Though the NBCCEDP provides a safety net for low-income women to access free breast and cervical cancer screening, this program does not address the historical and underlying barriers the women faced.

Public health research shows that health inequities reflect social conditions, such that those with relatively lower SES experience higher mortality from preventable and nonterminal diagnoses.52–54 If this is the case for preventable, nonterminal illnesses, then the issues become gravely exacerbated when considering the “death sentence” perception associated with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Participants in this study recognized that they faced conditions of systematic injustice with regard to health care access and financial and work challenges, and inevitably wanted an acute approach to the management of their breast cancer. We argue here that the participants similarly perceived themselves to be in a disadvantaged state vis-a-vis women with more financial resources.

Although to our knowledge we are unable to compare our findings with similar studies, our findings are in line with evidence that income inequality encumbers health-seeking behaviors and thus illness survival.55,56 Additionally, there are feelings of resentment and frustration and a range of behavioral modifications, from poorer political participation to a general mistrust of institutions and authority.57–59 As people move into higher SES levels they have better health outcomes than people in lower SES levels.10,60

Study Limitations

This study was limited in several ways. First, although there is no reason to believe a priori that study participants’ experiences are in any major way different from those of other women in this demographic, we recognize that our convenience sample does not facilitate the generalization of study findings to the general population. A small sample size is an inherent problem with qualitative studies, in which a deeper understanding of the relevant issues is the goal rather than an effort to determine more superficial norms for a broader sample. However, the women interviewed were fairly representative of the women participating in this program, and interviewing continued until we achieved response redundancy. The homogeneity of the study population should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. A larger sample size is needed to validate generalizability. Second, our qualitative data analysis focused on general themes relevant to the entire sample and does not reflect intrasample comparisons because the study design did not allow for exploring relationship differences between subgroups. Future studies should examine the geographical mapping of this complex population to further determine whether these outcomes are particularly problematic based on living situations. Finally, we were unable to interview women who never followed up after receiving their abnormal breast screening results. Study participants said they would follow up with their treatment even if they had to change providers, but the study was not designed to track these participants. Despite these limitations, our findings fill an existing gap in the breast cancer treatment literature. To our knowledge no study has captured real-time data in this population between the diagnostic and follow-up processes of the breast screening–treatment continuum.

Conclusion

Our results show an interlinkage between cognitive factors and social inequities that lead to health outcomes. Psychosocial context, structural and cultural, as well as the emotional findings influences behaviors along the treatment continuum. Social and economic determinants that underlie the broader social inequality result in continuous psychological stressors that lead to risk-taking health behavior, which in its simplest translation equals lack of timely health service utilization.56,61,62 Recognition that those living under the burden of health inequalities are never just the victims of circumstance, but rather active and rational agents, is essential.19 It is critical that public health research on breast cancer mortality highlight the significance of social injustice that gives rise to psychological stressors and focus on health-systems delivery change and individual empowerment.40,63

Even with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, many barriers will remain for poor women found to have abnormal screening results.21 Social injustices embedded within the follow-up and treatment processes and structurally within society must be addressed before breast cancer disparities can be eliminated. Of interest to policy makers, therefore, is whether new public-health interventions—as well as general improvements in health—can actually reduce inequities in health status between rich and poor groups in society. Interventions that focus solely on behavioral determinants without factoring in the social and economic determinants will not be effective in closing the gap.64 An increased emphasis on community engagement to spur social, political, and economic action to break down structural barriers is needed. The larger issue of what is fair and equitable in terms of health and wealth in the United States makes social justice the platform for action in moving toward health equity.

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practioners and Researchers.

What is already known on this topic?

Psychosocial factors, low socioeconomic status, stage of diagnosis, delayed treatment, individual characteristics, and treatment disparities are factors attributed to disparities in breast cancer screening and survival among low-income women.

What does this article add?

This study contributes an understanding about how inequities in the social environment of low-income women help to forge health-seeking decisions after receiving an abnormal breast screening result. Psychosocial context, structural and cultural barriers, lack of insurance, and emotional well-being were found to be key drivers in decision making and expand our understanding of the disparities in breast cancer in the context, culture, and value in which they exist for low-income disadvantaged women.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Quantitative efforts to identify how the factors identified in the study interrelate with the socioeconomic context in which people live and health systems should be explored in future research. Particularly, community-based participatory research studies should focus on the intentional development and integration of systemic and behavioral determinants in health promotion strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Public Health Consortium, Arnold School of Public Health, for the funding support of this study. We are also indebted to the Best Chance Network case managers who took time from busy schedules to discuss the study with their new case referrals and the women who gave us this opportunity to tell their stories.

References

- 1.Albain KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:984–992. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gluck S, Mamounas T. Improving outcomes in early-stage breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24(11 suppl 4):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breslin TM, Caughran J, Pettinga J, et al. Improving breast cancer care through a regional quality collaborative. Surgery. 2011;150:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derose KP, Gresenz CR, Ringel JS. Understanding disparities in health care access—and reducing them—through a focus on public health. Health Aff. 2011;30:1844–1851. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis LE, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2000. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barcenas CH, Wells J, Chong D, et al. Race as an independent risk factor for breast cancer survival: breast cancer outcomes from the Medical College of Georgia tumor registry. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10:59–63. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field TS, Buist DS, Doubeni C, et al. Disparities and survival among breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;(35):88–95. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Lian M, et al. The role of poverty rate and racial distribution in the geographic clustering of breast cancer survival among older women: a geographic and multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:554–561. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC, et al. Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987–2005) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:121–131. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320(7243):1200–1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paskett ED, Rushing J, D’Agostino R, Jr, et al. Cancer screening behaviors of low-income women: the impact of race. Womens Health. 1997;3:203–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. Cancer. 2007;109(S2):359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fair AM, Wujcik D, Lin JM, et al. Psychosocial determinants of mammography follow-up after receipt of abnormal mammography results in medically underserved women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1 suppl):71–94. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells BL, Horm JW. Stage at diagnosis in breast cancer: race and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1383–1385. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon NH. Socioeconomic factors and breast cancer in black and white Americans. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:55–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1022212018158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrante J, Chen P-H, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85:114–124. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113:1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman HP. Poverty, culture, and social injustice: determinants of cancer disparities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:72–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman HP, Chu KC. Determinants of cancer disparities: barriers to cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2005;14:655–669. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2005.06.002. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gostin LO, Powers M. What does social justice require for the public’s health? Public health ethics and policy imperatives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:1053–1060. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniels N. Justice, health and health care. In: Rhodes R, Battin M, Silvers A, editors. Medicine and Social Justice. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peter F. Health equity and social justice. J Appl Philos. 2001;18:159–170. doi: 10.1111/1468-5930.00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Rev ed. Boston, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steel DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Health. Volume 4: Social Psychological Aspects of Health. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan S, Kaplan R. Cognition and Environment. New York, NY: Preger; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braveman P, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, et al. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(suppl 1):S149–S155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leventhal H, Nerenz DR. The assessement of illness cognition. In: Karoly P, editor. Measurement Strategies in Health Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1985. pp. 517–554. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steel DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Health. Volume 4: Social Psychological Aspects of Health. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lantz PM, Mujahid M, Schwartz K, et al. The influence of race, ethnicity, and individual socioeconomic factors on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2173–2178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lantz PM, Weisman CS, Itani Z. A disease-specific Medicaid expansion for women. The Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000. Womens Health Issues. 2003;13:79–92. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NVivo [computer program]. Version 8. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cresswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strauss A, Corbin A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedure and Techniques. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miles M. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long E. Breast cancer in African-American women: review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Admi H, Hunter D, Trichopoulos D. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caplan LS, Helzlsouer KJ, Shapiro S, et al. Reasons for delay in breast cancer diagnosis. Prev Med. 1996;25:218–224. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drageset S, Lindstrm TC. Coping with a possible breast cancer diagnosis: demographic factors and social support. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuille KM. Using self-regulation theory to develop an intervention for cancer-related fatigue. Clin Nurse Spec. 2002;16:312–319. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanton AL, Snider PR. Coping with a breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:16–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alegria M, Sribney W, Perez D, et al. The role of patient activation on patient-provider communication and quality of care for US and foreign born Latino patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 3):534–541. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, et al. Patient-provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethn Health. 2009;14:107–130. doi: 10.1080/13557850802227031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheppard VB, Zambrana RE, O’Malley AS. Providing health care to low-income women: a matter of trust. Fam Pract. 2004;21:484–491. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wallace LS, DeVoe JE, Rogers ES, et al. Digging deeper: quality of patient-provider communication across Hispanic subgroups. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:240. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:144–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson LA, Zimmerman MA. Patient and physician perceptions of their relationship and patient satisfaction: a study of chronic disease management. Patient Educ Couns. 1993;20:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(93)90114-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hofrichter R. The politics of health inequities: contested terrain. In: Hofrichter R, editor. Health and Social Justice: Politics, Ideology, and Inequality in the Distribution of Disease. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartley M. Health Unequality: An Introduction to Theories, Concepts and Methods. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosma H, van de Mheen HD, Mackenbach JP. Social class in childhood and general health in adulthood: questionnaire study of contribution of psychological attributes. BMJ. 1999;318(7175):18–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marmot M. Inequalities in health. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:134–136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Wilkinson R. The Society and Population Health Reader: Income Inequality and Health. Vol 1. New York, NY: New Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, et al. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997;350(9073):235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baum F. Social capital: is it good for your health? Issues for a public health agenda. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:195–196. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.4.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Putnam R. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilkinson R. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Income Inequality and health: what does the literature tell us? Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:543–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brunner E, Marmot M. Social organization, stress and health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 6–30. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jarvis M, Wardle J. Social patterning of individual health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muntaner C. Power, politics, and social class. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:562. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Stoff DM, et al. Moving toward paradigm-shifting research in health disparities through translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary approaches. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S19–S24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]