Abstract

Prevention of neonatal infection-related mortality represents a significant global challenge particularly in the vulnerable premature population. The increased risk of death from sepsis is likely due to the specific immune deficits found in the neonate as compared to the adult. Stimulation of the neonatal immune system to prevent and or treat infection has been attempted in the past largely without success. In this review, we identify some of the known deficits in the neonatal immune system and their clinical impact, summarize previous attempts at immunomodulation and the outcomes of these interventions, and discuss the potential of novel immunomodulatory therapies to improve neonatal sepsis outcome.

Keywords: newborn, immunomodulation, adjuvant, IVIG, probiotic, mouse, neonatal, sepsis, treatment, cytokines, Toll-like receptor, innate immunity, adaptive immunity

Background and Introduction

Every year, more than one million newborns die from sepsis or serious infection the first four weeks of life1. Prevention of newborn infection therefore remains a significant global challenge. Neonatal healthcare providers routinely care for infants with risk factors, symptoms, or signs of sepsis, requiring immediate clinical evaluation and presumptive antibiotic coverage. The need for such timely intervention is due to the high risk of mortality in this vulnerable population that is likely the result of multiple immunologic differences between the neonate and older populations. The teleology of these immunological differences is believed to be focused on preventing preterm birth secondary to in utero inflammatory responses, reducing the likelihood of fetal rejection by the mother, and developing fetal immunologic tolerance2. While the quiescence of the fetal immune system is likely essential in utero, these responses ex utero may carry disadvantages, including impaired host defense against infection and weak neonatal vaccine responses that can impede efforts to protect this at risk population. Therefore, the newborn is relatively ill-equipped to deal with an infectious challenge and as a result exhibits increased morbidity and mortality compared to children and adults3,4. These risks are significantly greater in premature, critically-ill neonates with exposure to intrapartum infections, premature rupture of membranes, or in which invasive procedures and mechanical ventilation are required5. While numerous studies have identified molecular markers of neonatal sepsis to facilitate early diagnosis, there has been relatively less study of the distinct pathophysiology of neonatal sepsis. Comprehensive investigation into the individual immunological responses of neonatal sepsis may define functional immunodeficiencies that can be targeted to prevent or treat neonatal infection.

Neonatal immune function

Both innate and adaptive immunity are distinct at birth relative to adulthood6. Neonatal immune responses are generally TH2-skewed, being geared towards immune tolerance instead of towards defense from microbial infections [TH1 skewed] (Table 1)7–10. Neonatal antigen-presenting cells (APCs) demonstrate impaired production of TH1-polarizing cytokines (e.g., IL-12, interferon-γ that direct immune responses against microbial pathogens) and impaired up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules to most Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists2,11,12. Nevertheless, certain stimuli such as Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) induce adult-like responses via mechanisms that are not yet completely defined7,13,14. Additionally, neonatal T cells require increased stimulus in order to achieve adult-level responses7,13,14. Compared to adults, neonates manifest delayed, shortened, and decreased B cell responses that limit their responses to infection and vaccination7. Studies in adult mice using models of sepsis indicate that impairments in adaptive immunity result in poor survival15–17, but the impact of the distinct neonatal adaptive immune system on neonatal sepsis survival has not been defined. Of note, adjuvants directed at decreasing sepsis-induced adaptive immunodeficiencies (e.g., inhibition of T and B-cell apoptosis18 or enhancement of T cell function19) improve sepsis outcomes in preclinical adult animal models. However, because the adaptive immune system does not function exactly in the neonate as it does in the adult7, we must concede that therapies targeting adult sepsis-specific deficits may not work as effectively in neonates.

Table 1.

Deficits in Neonatal Adaptive Immune Function and the Proposed Clinical Impact.

| Adaptive Immune Deficit | Proposed Clinical Impact |

|---|---|

| Limited antecedent exposure of T cells to foreign antigens | Lack of rapid, strong, memory response |

| Greater requirement for CD4+ T cell stimulation | Decreased T cell activation, proliferation |

| TH2skewed and attenuated CD4+ T cell cytokine response | Decreased response to infection, particularly intracellular pathogens |

| Poor CD4+ T cell-dependent B cell stimulation | Poor antibody production |

| Decreased CD8+ T cell cytolytic activity | Decreased clearance of intracellularly infected cells |

| Abundant, potent T regulatory cell population present at birth | Inhibited TH1 T cell responses, decreased response to infection, limit vaccine responses of newborns |

| Maternal antibodies interfere with B cell antibody response | Attenuated antibody production |

| Weak humoral response, predominantly IgM | Poor opsonization and clearance of bacteria |

| Poor antibody response to polysaccharide antigens | Increased susceptibility to encapsulated organisms |

| Deficient CD40 ligand stimulation of B cells | Poor antibody production-lack of memory response |

| Underdeveloped spleen and lymph nodes | Poor antibody production, poor clearance of bacteria from blood |

The distinct function of the neonatal adaptive immune system renders the neonate especially dependent on the function of the innate immune system and on circulating maternal antibodies transferred during the last trimester, though these are deficient in the setting of prematurity. The neonatal innate immune system is also impaired compared to adults, likely contributing to their increased susceptibility to infection (Table 2)6,12,20. Neonates have fragile skin (preterm newborns), decreased circulating complement components (limiting opsonization/killing of pathogens), diminished expression of some antimicrobial proteins and peptides (APP), decreased production of type I interferons and TH1 polarizing cytokines (and a bias towards TH2-type responses), and quantitative and/or qualitative impairments in neutrophil, monocyte, macrophage, and dendritic cell function12. Neonatal leukocytes, particular under stress conditions, demonstrate diminished cellular functions necessary for bacterial clearance, including diminished responses to most TLR agonists (constituents of microbes), reduced production of cytokines/chemokines and APP, diapedesis, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and antigen presentation6,12. Neonates are also deficient in functional splenic follicules that filter blood and remove pathogens, further limiting bacterial clearance, and increasing the risk of fulminant infection.

Table 2.

Deficits in Neonatal Innate Immune Function and the Proposed Clinical Impact.

| Innate Immune Deficit | Proposed Clinical Impact |

|---|---|

| Fragile, easily disrupted skin (particularly in premature) | Portal of entry for microbes |

| Decreased serum complement components | Decreased complement-mediated killing and opsonization lead to poor bacterial clearance and decreased naïve B cell activation |

| Defective neutrophil amplification, mobilization, and function (phagocytosis, respiratory burst, lactoferrin and BPI production) | Poor bacterial clearance |

| Reduced MHC Class 2 expression on antigen presenting cells (APCs) | Poor T and B cell stimulation |

| Impaired APC function (decreased TH1 polarizing cytokine production, poor antigen presenting function, impaired mobilization, increased stimulation requirement to effect response) | Poor bacterial clearance |

| Depressed Natural Killer (NK) cell cytotoxic function | Poor clearance of cells infected with intracellular pathogens |

| Intrinsic immaturity of dendritic cells (DCs) | Poor antigen presenting function, poor memory response |

| Impaired cytokine production in response to pathogens | Poor chemotactic gradient formation, poor cellular recruitment to site of inflammation |

| Decreased neutrophil storage pool in bone marrow | Early depletion associated with poor sepsis outcomes |

| Decreased opsonin production | Decreased uptake and killing by phagocytes |

| Impaired response to certain TLR agonists, decreased down-stream signaling following TLR stimulation | Decreased chemotaxis and recruitment of innate cellular defenses |

The net effect of these deficits in neonatal immunity is to leave the neonate extremely susceptible to microbial invasion. There is therefore an unmet medical need to prevent and treat neonatal infection, and in this context, immunomodulatory agents are of considerable interest. Can the neonatal immune system be augmented in vivo in order to prevent and/or reduce sepsis mortality?

Attempts at Neonatal Immunomodulation

Experimentally and theoretically sound methods of immunomodulation directed at improving sepsis outcomes by correcting some neonatal immune deficits have been attempted without major improvement (Table 3)21–33. Therapies that enhance the quantity and/or quality of neutrophils, including granulocyte transfusions, GM-CSF, and G-CSF have been studied in human neonates34–38. These agents increase circulating numbers of neutrophils and appear to be safe, but have thus far been unsuccessful at significantly reducing neonatal sepsis mortality21,22. The administration of intravenous immmunogoblulin (IVIG) (polyclonal and monoclonal) administration has been aimed at both prevention and treatment of bacterial infection in neonates39,40–48, but meta-analyses have demonstrated only a marginal clinical benefit in prevention and there is insufficient data at present to routinely recommend IVIG for treatment of neonatal sepsis26. To more fully address the latter question of whether IVIG reduces sepsis (suspected or proven) mortality, a multi-center, international, double-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial (International Neonatal Immunotherapy Study) has been completed with publication of the results anticipated in 2009. Other therapies such as activated protein C49 and pentoxfylline31,32 (currently being evaluated in a phase II trial as an adjunctive treatment for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in premature infants [clinicaltrials.gov trial #NCT00271336]) have shown some promise, although future evaluation is warranted as their mechanisms of action are incompletely characterized and dangerous side effects (increased risk of bleeding) remain a concern with activated protein C50. Other potential immunomodulatory targets include reduction of oxidative stress and amino acid supplementation during periods of critical illness. Melatonin, which reduced oxidative stress in neonatal animal models51 and free radical production in human neonates52, was shown to reduce markers of inflammation and sepsis mortality in a very small study52. Further investigation may be warranted in larger randomized controlled clinical trials to better assess the potential benefit of melatonin. When glutamine, an amino acid important for repair and growth of rapidly dividing tissues, was supplemented to critically ill adults, reduced rates of infection were noted53–55. However, glutamine supplementation did not reduce nosocomial infections in preterm infants30,56 or morbidity and mortality57. As a ‘therapy’ with known immunologic benefit6,58,59, human milk feeding has been associated with reduced infection in both term and preterm infants6,60–63, and should be actively pursued.

Table 3. Attempts at Neonatal Immunomodulation and Impact on Sepsis Survival.

Numbers in parentheses represent references at the end of the text.

| Immunomodulation Strategy | Proposed Benefit | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Granulocyte transfusion | Increase functional granulocytes (PMNs) | No change in sepsis mortality (21) |

| GM-CSF, G-CSF | Stimulate proliferation and maturation of myeloid precursors in the bone marrow and modulate functions of mature PMNs at the site of infection | No change in sepsis mortality (34–38) |

| IVIG (monoclonal) | Increase bacteria-specific serum antibody titers | No change in sepsis mortality or efficacy of sepsis prevention (23,24,40,42) |

| IVIG (polyclonal) | Bind to cell surface receptors, provide opsonic activity, activate complement, promote antibody dependent cytotoxicity | Small (~3%) decrease in sepsis incidence, meta-analysis showed reduction in sepsis mortality with borderline statistical significance, INIS trial in progress (25,26,39,41,43–48) |

| Probiotics | Increase barrier to translocation of bacteria and bacterial products across mucosa, competitive exclusion of potential pathogens, modification of host response to microbial products | Limited data, reduction in NEC and NEC/sepsis mortality (27) |

| Breast milk | Multiple mechanisms: contains cellular defenses, IgA, APPs, probiotics, gut growth factors | Clear proven reduction in neonatal infectious mortality (28,58–63) |

| Activated protein C | Mechanism unclear | Limited data, no change in sepsis mortality, safety concerns (29,49–50) |

| Glutamine | Enhance gut integrity and immune function, and decrease bacterial translocation | No change in sepsis mortality (30,53,56,57) |

| Pentoxifylline | Reduce TNF-α and IL-6 synthesis | Limited data, reduction in sepsis mortality (31,32) |

| Anti-endotoxin antibodies | Decrease detrimental effects of endotoxin | Single small study, no change in mortality (33) |

Role of probiotics in immunomodulation

As the largest immune organ, the intestine serves as the major nexus of interaction with the external environment. The innate immune system of the intestine serves as a selective barrier to the post-natal presence of microbes and food antigens in order to prevent overwhelming systemic infection. At birth, the sterile intestine is rapidly colonized with microorganisms from maternal and environmental sources. Commensal microbes participate in health of the individual by playing roles in nutrition and in gut development64. Bacterial colonization of preterm infants differs from that of healthy full-term infants because of the methods of neonatal care (widespread prophylaxis with antibiotics, parenteral nutrition, and feeding in incubators) that may delay or impair colonization. The effect of antibiotics on the developing GI tract is incompletely understood, but recent studies in neonatal rodents demonstrate that the use of the ampicillin-like antibiotic, clomoxyl, alters development of intestinal gene expression65. The short and long-term effects of these antibiotic-driven alterations in the GI microbiota (>500 species of microbes are known to reside in the human gastrointestinal tract64,66) are the subject of intense research. The interaction between the mucosal immune system and the microbiota may be critical and the absence of this relationship may play a role in the development of autoimmune pathology and allergy. Probiotics have been successfully used as immunomodulators in the prevention and treatment of allergies in children67,68, suggesting that modification of the relationship between the intestine and commensal organisms helps shape the immunological network of the host and therefore could serve as a target for immunomodulation in premature neonates.

Recent studies in mice demonstrating an increased susceptibility to hemorrhagic colitis after eradication of intestinal bacteria suggest that the epithelium and resident immune cells do not simply tolerate commensal organisms but are dependent on them for protection69. Commensal bacteria express molecules such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Gram-negative bacteria), lipoteichoic acid (LTA; Gram-positive bacteria), and bacterial lipoproteins (BLPs, both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria), that engage intestinal epithelial TLRs. The resultant tonic TLR signaling, enhances the ability of the epithelial surface to withstand chemical or inflammatory mediator-induced injury while also priming the surface for enhanced repair responses69,70 (Fig. 1). This is due in part to selective coupling of TLR pathways in intestinal epithelial cells to production of anti-inflammatory and repair-enhancing cytokines71. The importance of TLR expression and stimulation in the development of NEC was highlighted in a recent report in neonatal mice indicating that over-expression of TLR4, following hypoxia or remote infection, was associated with a decreased ability of the intestine to withstand damage as well as an impairment in intestinal repair mechanisms72,73. Thus, either the disruption of gut TLR signaling or the removal of TLR agonists compromises the ability of the intestinal surface to protect and repair itself in the face of an inflammatory or infectious insult69,70,74 increasing the risk of bacterial translocation and the development of endotoxemia, sepsis, and/or NEC.

Figure 1. Interaction of Microbiota and Neonatal Intestine.

The interaction between intestinal bacteria and intestinal epithelium is necessary for homeostasis and normal function of repair mechanisms. Disruption of this interaction, through the use of antibiotics or via stress to the organism (i.e. remote infection or hypoxia), results in loss of homeostasis and degradation of the intestinal boundaries with subsequent microbial translocation.

Preterm human infants randomly assigned to receive a daily feeding supplement of a probiotic mixture compared to non-probiotic administered control infants had a relative risk reduction in mortality, incidence of NEC, and late onset sepsis27,75. However, a large multicenter trial conducted in 12 Italian neonatal intensive care units on 565 patients did not elicit a statistically significant beneficial effect of probiotic (Lactobacillus GG) on NEC or sepsis76. In a recent meta-analysis, probiotic treatment was shown to reduce the incidence of higher Bell stage NEC (stage 2 and higher) and mortality in preterm infants less than 1500 grams77. Whether the differences in outcomes in these studies are associated with the use of different probiotic preparations, a different baseline incidence of NEC and sepsis in the different NICUs, or other factors such as breast milk feeding remain speculative. Previous studies suggest that human breast milk contains beneficial microbes that are independent of those found in the areolar skin78. The role of human milk, itself replete with innate immune effectors including APP and TLR modulators79,80, versus formula feedings in the probiotic studies mentioned above was not critically examined but is clearly worthy of future study. Additional studies are also necessary to clarify whether types of probiotics (live or inactivated bacteria or their corresponding TLR agonists) and their dosage have a differential impact on NEC prevention and/or sepsis survival, as well as on long-term outcome measures including safety.

Where do we go from here? In vitro studies light the way…

Many in vitro studies of neonatal leukocytes have identified functional deficiencies, pointing to potential future immunomodulatory therapies that may enhance specific facets of neonatal immune function, such as cytokine and APP production as well as phagocytosis. To facilitate the translation of this in vitro data to the bedside, preclinical models in animals have been employed. For example, studies of sepsis in adult animals have guided biopharmaceutical development of novel sepsis therapies including probiotics81, caspase inhibitors18, glucocorticoid-induced TNF-α receptor stimulation19, TLR modulation82–84, as well as glucocorticoids, anti-endotoxin antibodies, IL-1 receptor antagonists, anti-TNF-α antibodies, recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI)85, and others86. However, much of the descriptive and mechanistic work characterizing the immune response in sepsis has been done using adult animal models that may not necessarily apply to neonates given the distinct function of neonatal immune system12.

Innate immune system enhancement via TLR stimulation

Following the description of TLRs in humans87, the characterization of their respective effects has grown exponentially. Widely expressed by invertebrate and vertebrate animals, TLRs detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), triggering host cell cytokine and antimicrobial effector responses88,89 (Fig. 2). TLR-triggered responses are differentially regulated at the genetic level and constitute an adaptive component of the innate immune system. For example, upon restimulation of leukocytes with TLR agonists, potentially harmful excessive inflammatory cytokine production is reduced while antimicrobial genes remain active90. The contribution of TLR activation, signaling, and expression to human disease is currently an area of intensive study across many medical disciplines91.

Figure 2. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) and Their Respective Agonists.

Schematic representation of toll-like receptors, both cell surface and endocytic, as well as their respective ligands. Stimulation of these receptors causes enhanced immune function through increased cellular cytokine production and improvement of antimicrobial effector mechanisms such as cellular phagocytosis and antimicrobial protein and peptide (APP) production. LTA-lipotechoic acid. PG-peptidoglycan. LPS-lipopolysaccharide.

In the context of well-described in vitro deficits in neonatal immunity, the TLRs prominent role in innate immunity sparked studies to assess whether TLR activation improves neonatal cellular responses92–98. Major differences exist between newborns and adults in TLR-mediated monocyte activation, but that these differences are not uniform across all TLRs99. Although neonatal APCs demonstrate impaired production of TH1-polarizing cytokines (eg, TNF-α and IL-12) and impaired up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules in responses to agonists of TLRs 1–7, responses to TLR8 agonists are remarkably preserved99–101. Impaired TLR signaling also contributes to reduced neonatal leukocyte responses to bacterial cell wall products, potentially contributing to neonatal risk of infection97.

Impairment in the ability of human neonatal blood monocytes to produce TNF-α in response to TLR agonists is due to the inhibitory effects of plasma adenosine, which binds its specific adenosine receptor thereby increasing intracellular concentrations of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)102,103. Neonatal blood plasma contains relatively high concentrations of adenosine and neonatal cord blood mononuclear cells demonstrate increased sensitivity to the cAMP-mediated inhibitory effects of adenosine104. cAMP inhibits production of multiple TH1 polarizing cytokines while preserving production of counter-regulatory cytokines such as IL-10. Thus, the adenosine system thus plays important roles in limiting TLR2-mediated blood monocyte production of TNF-α and other TH1 polarizing cytokines at birth, during exposure of the neonate to microbial flora during the birth process12. TLR8 agonists, including single stranded RNAs and synthetic imidazoquinoline compounds, represent an important exception to he general pattern of impaired human neonatal monocyte responses to TLR agonists101,105.

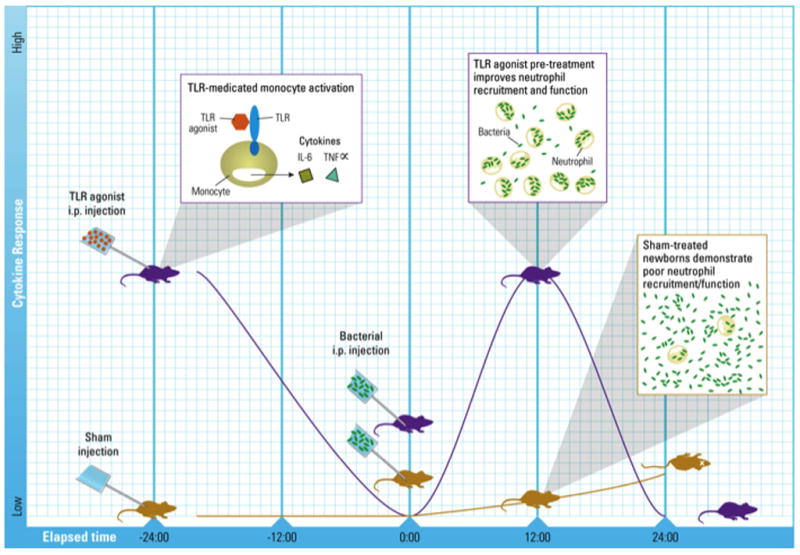

Recent in vivo studies have explored whether priming of an innate immune response by pre-treatment of neonatal mice with TLR agonists improves outcomes of infection. Priming using TLR9 agonist (CpG) was protective against L. monocytogenes or neurotropic Tacaribe arenavirus (a powerfully lethal murine-specific virus) in single-pathogen challenge murine neonatal sepsis models106,107. Using a neonatal murine model of polymicrobial sepsis108, we showed that a single small dose prior to sepsis with TLR7/8 agonist (the imidazoquinoline resiquimod), or TLR4 agonist (LPS), was able to reduce polymicrobial sepsis mortality by 25 and 40% respectively over sham-treated septic animals (In press-Wynn et. al. Blood). Importantly, we found TLR agonist priming was not uniformly beneficial, as TLR3 agonist pretreated mice had no advantage over sham-treated septic animals. TLR7/8 and TLR4 agonist pretreatment enhanced but shortened the systemic inflammatory response seen with sepsis, decreased bacteremia, and improved survival, but were associated with associated with distinct enhancement of innate immune function including increased PMN recruitment, and reactive oxygen species production [TLR4] or phagocytic function [TLR7/8] (Fig. 3). In contrast to results in adult mice, in which the absence of the adaptive immune system was associated with significantly higher mortality (~60% higher than wild-type), there was no difference in neonatal sepsis mortality when compared to the wild-type mice (In press-Wynn et. al. Blood), emphasizing the dependence of the neonate on innate immunity for sepsis survival. Lastly, we showed that the survival benefit conferred by pretreatment with TLR agonists were also evident in neonatal mice lacking an adaptive immune system, confirming that the benefits of TLR agonist pretreatment are through stimulation of innate immunity alone. Thus, in marked contrast to adults, in whom absence or dysfunction of the adaptive immune system negatively affects survival following polymicrobial sepsis, neonates demonstrate a dependence on innate immune function that is improved through select TLR stimulation resulting in increased sepsis survival with minimal or no contribution of the adaptive immune system.

Figure 3. Effect of TLR agonist Pretreatment on Sepsis Survival, Cytokine Production, Bacteremia, and Innate Cellular Function in Neonatal Mice.

Systemic administration of select TLR agonists prior to the initiation of experimental polymicrobial sepsis significantly reduces murine neonatal mortality and is associated with a more robust but shortened inflammatory response and unique improvements in cell function (increased phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species production) with associated decreases in bacteremia as compared to saline pretreated neonatal mice.

Potential for Prophylactic Immunomodulation

Efforts aimed at improving neonatal sepsis survival by using adjuvants must take into consideration the unique aspects of neonatal immunity and sepsis in order to develop age-appropriate therapies. Specific TLR stimulation appears to effectively address some of the known deficits unique to neonatal immunity, including the long-appreciated impairment in phagocytic function during stress conditions12,109,110. The efficacy of TLR agonist pretreatment in improving survival in preclinical models of severe infection is thus of great interest. Such a prophylactic approach is particularly appropriate for low-birth weight extremely premature neonates, a group at high risk for infection111 due to particularly impaired innate immune responses (eg, skin immaturity, particularly low complement and APP levels, and deficiency of passive immunoglobulins) as well as exposure to multiple invasive procedures, including intubation, central venous line placement, delayed feeding, and monitoring devices. Premature infants suffer the highest sepsis mortality of any population5 and early onset lethal sepsis (during the first week of life) is predominantly due to Gram-negative bacteria111. If a prophylactic protective immune response could be generated that would persist through this crucial time, it is likely that the mortality within this population could be dramatically reduced. As a result, potential prophylactic approaches directed at priming the neonatal immune system before a potential insult are of substantial interest. Priming innate immunity might also serve other immunocompromised medical populations such as those who have received chemotherapy or those who are pharmacologically immunosuppressed.

Potential Adverse Effects of Immunomodulation

Immunomodulation is not without theoretical risk of unwanted side effects. Improvements in innate cellular function might come at the expense of increased autoimmunity or other inflammatory damage. Because neonates with antenatal conditions which produce excessive inflammation (such as chorioamnionitis) are known to have associated pathology such as periventricular leukomalacia or chronic lung disease112, the notion of augmenting the immune system response must be tempered by concerns for potential untoward effects. The recent discovery that effects of TLR stimulation, including cytokine production and antimicrobial effector mechanisms, are differentially regulated suggests that selective immunomodulatory effects can be elicited through specific pharmacologic targeting90. TLR agonists, such as Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (a TLR2 and 4 agonist113), are already given to neonates at birth to reduce tuberculosis. More studies examining the effects of TLR stimulation in vivo are necessary in neonatal animal models, including non-human primates, whose TLR pathways more closely conform to those of humans114, with emphasis on determination of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and potential side effects.

Summary

Modulation of innate immune responses provides fresh opportunities for improving sepsis survival in neonates. Targeting high risk populations for selective immunoprophylaxis to enhance host defense against bacterial infection is a promising approach whose realization will require further progress regarding mechanisms of action, pharmacologic properties, and safety.

References

- 1.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005 Mar 5–11;365(9462):891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marodi L. Innate cellular immune responses in newborns. Clin Immunol. 2006 Feb-Mar;118(2–3):137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):1546–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton P, Kalil AC, Nadel S, Goldstein B, Okhuysen-Cawley R, Brilli RJ, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis. Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):7–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinot A, Leclerc F, Cremer R, Leteurtre S, Fourier C, Hue V. Sepsis in neonates and children: definitions, epidemiology, and outcome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997 Aug;13(4):277–81. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence RM, Pane CA. Human breast milk: current concepts of immunology and infectious diseases. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007 Jan;37(1):7–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004 Jul;4(7):553–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegrist CA. The challenges of vaccine responses in early life: selected examples. J Comp Pathol. 2007 Jul;137( Suppl 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanekom WA. The immune response to BCG vaccination of newborns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005 Dec;1062:69–78. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchant A, Goldman M. T cell-mediated immune responses in human newborns: ready to learn? Clin Exp Immunol. 2005 Jul;141(1):10–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byun HJ, Jung WW, Lee JB, Chung HY, Sul D, Kim SJ, et al. An evaluation of the neonatal immune system using a listeria infection model. Neonatology. 2007;92(2):83–90. doi: 10.1159/000100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 May;7(5):379–90. doi: 10.1038/nri2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonnecke BJ, Waters WR, Foote MR, Palmer MV, Miller BL, Johnson TE, et al. Development of an adult-like cell-mediated immune response in calves after early vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Dairy Sci. 2005 Jan;88(1):195–210. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchant A, Appay V, Van Der Sande M, Dulphy N, Liesnard C, Kidd M, et al. Mature CD8(+) T lymphocyte response to viral infection during fetal life. J Clin Invest. 2003 Jun;111(11):1747–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI17470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scumpia PO, McAuliffe PF, O’Malley KA, Ungaro R, Uchida T, Matsumoto T, et al. CD11c+ dendritic cells are required for survival in murine polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol. 2005 Sep 1;175(5):3282–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Grayson MH, Osborne DF, Wagner TH, et al. Depletion of dendritic cells, but not macrophages, in patients with sepsis. J Immunol. 2002 Mar 1;168(5):2493–500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Schmieg RE, Jr, Hui JJ, Chang KC, et al. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J Immunol. 2001 Jun 1;166(11):6952–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Swanson PE, Tinsley KW, Hui JJ, Klender P, et al. Caspase inhibitors improve survival in sepsis: a critical role of the lymphocyte. Nat Immunol. 2000 Dec;1(6):496–501. doi: 10.1038/82741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scumpia PO, Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Weinstein JS, Wynn JL, Winfield RD, et al. Treatment with GITR agonistic antibody corrects adaptive immune dysfunction in sepsis. Blood. 2007 Aug 9; doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrova A, Mehta R. Dysfunction of innate immunity and associated pathology in neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2007 Feb;74(2):185–91. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohan P, Brocklehurst P. Granulocyte transfusions for neonates with confirmed or suspected sepsis and neutropaenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD003956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr R, Modi N, Dore C. G-CSF and GM-CSF for treating or preventing neonatal infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeJonge M, Burchfield D, Bloom B, Duenas M, Walker W, Polak M, et al. Clinical trial of safety and efficacy of INH-A21 for the prevention of nosocomial staphylococcal bloodstream infection in premature infants. J Pediatr. 2007 Sep;151(3):260–5. 5 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamin DK, Jr, Schelonka R, White R, Holley HP, Jr, Bifano E, Cummings J, et al. A blinded, randomized, multicenter study of an intravenous Staphylococcus aureus immune globulin. J Perinatol. 2006;26(5):290. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlsson A, Lacy JB. Intravenous immunoglobulin for preventing infection in preterm and/or low-birth-weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD000361. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000361.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlsson A, Lacy JB. Intravenous immunoglobulin for suspected or subsequently proven infection in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD001239. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001239.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin HC, Su BH, Chen AC, Lin TW, Tsai CH, Yeh TF, et al. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2005 Jan;115(1):1–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.el-Mohandes AE, Picard MB, Simmens SJ, Keiser JF. Use of human milk in the intensive care nursery decreases the incidence of nosocomial sepsis. J Perinatol. 1997 Mar-Apr;17(2):130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein B, Nadel S, Peters M, Barton R, Machado F, Levy H, et al. ENHANCE: results of a global open-label trial of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006 May;7(3):200–11. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000217470.68764.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Poole WK, Oh W, et al. Parenteral glutamine supplementation does not reduce the risk of mortality or late-onset sepsis in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):1209–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haque K, Mohan P. Pentoxifylline for neonatal sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004205. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauterbach R, Pawlik D, Kowalczyk D, Ksycinski W, Helwich E, Zembala M. Effect of the immunomodulating agent, pentoxifylline, in the treatment of sepsis in prematurely delivered infants: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Crit Care Med. 1999 Apr;27(4):807–14. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199904000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adhikari M, Coovadia HM, Gaffin SL, Brock-Utne JG, Marivate M, Pudifin DJ. Septicaemic low birthweight neonates treated with human antibodies to endotoxin. Arch Dis Child. 1985 Apr;60(4):382–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad A, Laborada G, Bussel J, Nesin M. Comparison of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and placebo for treatment of septic preterm infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Nov;21(11):1061–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilgin K, Yaramis A, Haspolat K, Tas MA, Gunbey S, Derman O. A randomized trial of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in neonates with sepsis and neutropenia. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan;107(1):36–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr R, Modi N, Dore CJ, El-Rifai R, Lindo D. A randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in human newborns less than 32 weeks gestation. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4 Pt 1):796–802. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kucukoduk S, Sezer T, Yildiran A, Albayrak D. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of early administration of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to non-neutropenic preterm newborns between 33 and 36 weeks with presumed sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(12):893–7. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura E, Procianoy RS, Bittar C, Miura CS, Miura MS, Mello C, et al. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration to preterm infants with the clinical diagnosis of early-onset sepsis. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan;107(1):30–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg K, Fasth A, Berger A, Eibl M, Isacson K, Lischka A, et al. Preterm infants with low immunoglobulin G levels have increased risk of neonatal sepsis but do not benefit from prophylactic immunoglobulin G. J Pediatr. 2000 Nov;137(5):623–8. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloom B, Schelonka R, Kueser T, Walker W, Jung E, Kaufman D, et al. Multicenter study to assess safety and efficacy of INH-A21, a donor-selected human staphylococcal immunoglobulin, for prevention of nosocomial infections in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005 Oct;24(10):858–66. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000180504.66437.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shenoi A, Nagesh NK, Maiya PP, Bhat SR, Subba Rao SD. Multicenter randomized placebo controlled trial of therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin in decreasing mortality due to neonatal sepsis. Indian Pediatr. 1999 Nov;36(11):1113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lassiter HA, Robinson TW, Brown MS, Hall DC, Hill HR, Christensen RD. Effect of intravenous immunoglobulin G on the deposition of immunoglobulin G and C3 onto type III group B streptococcus and Escherichia coli K1. J Perinatol. 1996 Sep-Oct;16(5):346–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atici A, Satar M, Karabay A, Yilmaz M. Intravenous immunoglobulin for prophylaxis of nosocomial sepsis. Indian J Pediatr. 1996 Jul-Aug;63(4):517–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02905726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haque KN, Remo C, Bahakim H. Comparison of two types of intravenous immunoglobulins in the treatment of neonatal sepsis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995 Aug;101(2):328–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb08359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisman LE, Stoll BJ, Kueser TJ, Rubio TT, Frank CG, Heiman HS, et al. Intravenous immune globulin prophylaxis of late-onset sepsis in premature neonates. J Pediatr. 1994 Dec;125(6 Pt 1):922–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisman LE, Stoll BJ, Kueser TJ, Rubio TT, Frank CG, Heiman HS, et al. Intravenous immune globulin therapy for early-onset sepsis in premature neonates. J Pediatr. 1992 Sep;121(3):434–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clapp DW, Kliegman RM, Baley JE, Shenker N, Kyllonen K, Fanaroff AA, et al. Use of intravenously administered immune globulin to prevent nosocomial sepsis in low birth weight infants: report of a pilot study. J Pediatr. 1989 Dec;115(6):973–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80753-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haque KN, Zaidi MH, Haque SK, Bahakim H, el-Hazmi M, el-Swailam M. Intravenous immunoglobulin for prevention of sepsis in preterm and low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986 Nov-Dec;5(6):622–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kylat RI, Ohlsson A. Recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005385. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005385.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nadel S, Goldstein B, Williams MD, Dalton H, Peters M, Macias WL, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis: a multicentre phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007 Mar 10;369(9564):836–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ozdemir D, Uysal N, Tugyan K, Gonenc S, Acikgoz O, Aksu I, et al. The effect of melatonin on endotoxemia-induced intestinal apoptosis and oxidative stress in infant rats. Intensive Care Med. 2007 Mar;33(3):511–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0492-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gitto E, Karbownik M, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Cuzzocrea S, Chiurazzi P, et al. Effects of melatonin treatment in septic newborns. Pediatr Res. 2001 Dec;50(6):756–60. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novak F, Heyland DK, Avenell A, Drover JW, Su X. Glutamine supplementation in serious illness: a systematic review of the evidence. Crit Care Med. 2002 Sep;30(9):2022–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray SM, Pindoria S. Nutrition support for bone marrow transplant patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002920. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houdijk AP, Rijnsburger ER, Jansen J, Wesdorp RI, Weiss JK, McCamish MA, et al. Randomised trial of glutamine-enriched enteral nutrition on infectious morbidity in patients with multiple trauma. Lancet. 1998 Sep 5;352(9130):772–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaughn P, Thomas P, Clark R, Neu J. Enteral glutamine supplementation and morbidity in low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2003 Jun;142(6):662–8. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tubman TR, Thompson SW, McGuire W. Glutamine supplementation to prevent morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001457. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001457.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanson LA, Korotkova M. The role of breastfeeding in prevention of neonatal infection. Semin Neonatol. 2002 Aug;7(4):275–81. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newburg DS, Walker WA. Protection of the neonate by the innate immune system of developing gut and of human milk. Pediatr Res. 2007 Jan;61(1):2–8. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250274.68571.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA. Differences in morbidity between breast-fed and formula-fed infants. J Pediatr. 1995 May;126(5 Pt 1):696–702. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. Bmj. 1990 Jan 6;300(6716):11–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6716.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hylander MA, Strobino DM, Dhanireddy R. Human milk feedings and infection among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1998 Sep;102(3):E38. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics. 1999 Jun;103(6 Pt 1):1150–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hooper LV. Bacterial contributions to mammalian gut development. Trends Microbiol. 2004 Mar;12(3):129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schumann A, Nutten S, Donnicola D, Comelli EM, Mansourian R, Cherbut C, et al. Neonatal antibiotic treatment alters gastrointestinal tract developmental gene expression and intestinal barrier transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2005 Oct 17;23(2):235–45. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00057.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001 May 11;292(5519):1115–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1058709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pohjavuori E, Viljanen M, Korpela R, Kuitunen M, Tiittanen M, Vaarala O, et al. Lactobacillus GG effect in increasing IFN-gamma production in infants with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Jul;114(1):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marschan E, Kuitunen M, Kukkonen K, Poussa T, Sarnesto A, Haahtela T, et al. Probiotics in infancy induce protective immune profiles that are characteristic for chronic low-grade inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008 Feb 11; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004 Jul 23;118(2):229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Savidge TC, Newman PG, Pan WH, Weng MQ, Shi HN, McCormick BA, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced human enterocyte tolerance to cytokine-mediated interleukin-8 production may occur independently of TLR-4/MD-2 signaling. Pediatr Res. 2006 Jan;59(1):89–95. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000195101.74184.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin CR, Walker WA. Intestinal immune defences and the inflammatory response in necrotising enterocolitis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006 Oct;11(5):369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jilling T, Simon D, Lu J, Meng FJ, Li D, Schy R, et al. The roles of bacteria and TLR4 in rat and murine models of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol. 2006 Sep 1;177(5):3273–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gribar SC, Anand RJ, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. The role of epithelial Toll-like receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2008 Mar;83(3):493–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madara J. Building an intestine--architectural contributions of commensal bacteria. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 14;351(16):1685–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr042621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bin-Nun A, Bromiker R, Wilschanski M, Kaplan M, Rudensky B, Caplan M, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr. 2005 Aug;147(2):192–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dani C, Biadaioli R, Bertini G, Martelli E, Rubaltelli FF. Probiotics feeding in prevention of urinary tract infection, bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. A prospective double-blind study. Biol Neonate. 2002 Aug;82(2):103–8. doi: 10.1159/000063096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alfaleh K, Bassler D. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005496. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin R, Heilig HG, Zoetendal EG, Jimenez E, Fernandez L, Smidt H, et al. Cultivation-independent assessment of the bacterial diversity of breast milk among healthy women. Res Microbiol. 2007 Jan-Feb;158(1):31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Phadke SM, Deslouches B, Hileman SE, Montelaro RC, Wiesenfeld HC, Mietzner TA. Antimicrobial peptides in mucosal secretions: the importance of local secretions in mitigating infection. J Nutr. 2005 May;135(5):1289–93. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.LeBouder E, Rey-Nores JE, Raby AC, Affolter M, Vidal K, Thornton CA, et al. Modulation of neonatal microbial recognition: TLR-mediated innate immune responses are specifically and differentially modulated by human milk. J Immunol. 2006 Mar 15;176(6):3742–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tok D, Ilkgul O, Bengmark S, Aydede H, Erhan Y, Taneli F, et al. Pretreatment with pro- and synbiotics reduces peritonitis-induced acute lung injury in rats. J Trauma. 2007 Apr;62(4):880–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236019.00650.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weighardt H, Feterowski C, Veit M, Rump M, Wagner H, Holzmann B. Increased resistance against acute polymicrobial sepsis in mice challenged with immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides is related to an enhanced innate effector cell response. J Immunol. 2000 Oct 15;165(8):4537–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feterowski C, Weighardt H, Emmanuilidis K, Hartung T, Holzmann B. Immune protection against septic peritonitis in endotoxin-primed mice is related to reduced neutrophil apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 2001 Apr;31(4):1268–77. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1268::aid-immu1268>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feterowski C, Novotny A, Kaiser-Moore S, Muhlradt PF, Rossmann-Bloeck T, Rump M, et al. Attenuated pathogenesis of polymicrobial peritonitis in mice after TLR2 agonist pre-treatment involves ST2 up-regulation. Int Immunol. 2005 Aug;17(8):1035–46. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levin M, Quint PA, Goldstein B, Barton P, Bradley JS, Shemie SD, et al. Recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) as adjunctive treatment for children with severe meningococcal sepsis: a randomised trial. rBPI21 Meningococcal Sepsis Study Group. Lancet. 2000 Sep 16;356(9234):961–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marshall JC. Such stuff as dreams are made on: mediator-directed therapy in sepsis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 May;2(5):391–405. doi: 10.1038/nrd1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997 Jul 24;388(6640):394–7. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007 Feb;19(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Doyle SE, O’Connell RM, Miranda GA, Vaidya SA, Chow EK, Liu PT, et al. Toll-like receptors induce a phagocytic gene program through p38. J Exp Med. 2004 Jan 5;199(1):81–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007 Jun 21;447(7147):972–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007 May;13(5):552–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Wit D, Tonon S, Olislagers V, Goriely S, Boutriaux M, Goldman M, et al. Impaired responses to toll-like receptor 4 and toll-like receptor 3 ligands in human cord blood. J Autoimmun. 2003 Nov;21(3):277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yan SR, Qing G, Byers DM, Stadnyk AW, Al-Hertani W, Bortolussi R. Role of MyD88 in diminished tumor necrosis factor alpha production by newborn mononuclear cells in response to lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2004 Mar;72(3):1223–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1223-1229.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schaub B, Bellou A, Gibbons FK, Velasco G, Campo M, He H, et al. TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation differentially induce cytokine secretion in human neonatal, adult, and murine mononuclear cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004 Sep;24(9):543–52. doi: 10.1089/jir.2004.24.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aksoy E, Albarani V, Nguyen M, Laes JF, Ruelle JL, De Wit D, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 3-dependent responses to lipopolysaccharide are selectively blunted in cord blood cells. Blood. 2007 Apr 1;109(7):2887–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sadeghi K, Berger A, Langgartner M, Prusa AR, Hayde M, Herkner K, et al. Immaturity of infection control in preterm and term newborns is associated with impaired toll-like receptor signaling. J Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 15;195(2):296–302. doi: 10.1086/509892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Al-Hertani W, Yan SR, Byers DM, Bortolussi R. Human newborn polymorphonuclear neutrophils exhibit decreased levels of MyD88 and attenuated p38 phosphorylation in response to lipopolysaccharide. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(2):E44–53. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i2.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Krumbiegel D, Zepp F, Meyer CU. Combined Toll-like receptor agonists synergistically increase production of inflammatory cytokines in human neonatal dendritic cells. Hum Immunol. 2007 Oct;68(10):813–22. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Levy O, Zarember KA, Roy RM, Cywes C, Godowski PJ, Wessels MR. Selective impairment of TLR-mediated innate immunity in human newborns: neonatal blood plasma reduces monocyte TNF-alpha induction by bacterial lipopeptides, lipopolysaccharide, and imiquimod, but preserves the response to R-848. J Immunol. 2004 Oct 1;173(7):4627–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Levy O. Innate immunity of the human newborn: distinct cytokine responses to LPS and other Toll-like receptor agonists. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11(2):113–6. doi: 10.1179/096805105X37376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Levy O, Suter EE, Miller RL, Wessels MR. Unique efficacy of Toll-like receptor 8 agonists in activating human neonatal antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2006 Aug 15;108(4):1284–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004 Jan;25(1):33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sitkovsky M, Lukashev D. Regulation of immune cells by local-tissue oxygen tension: HIF1 alpha and adenosine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005 Sep;5(9):712–21. doi: 10.1038/nri1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Levy O, Coughlin M, Cronstein BN, Roy RM, Desai A, Wessels MR. The adenosine system selectively inhibits TLR-mediated TNF-alpha production in the human newborn. J Immunol. 2006 Aug 1;177(3):1956–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Philbin VJ, Levy O. Immunostimulatory activity of Toll-like receptor 8 agonists towards human leucocytes: basic mechanisms and translational opportunities. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007 Dec;35(Pt 6):1485–91. doi: 10.1042/BST0351485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ito S, Ishii KJ, Gursel M, Shirotra H, Ihata A, Klinman DM. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhance neonatal resistance to Listeria infection. J Immunol. 2005 Jan 15;174(2):777–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pedras-Vasconcelos JA, Goucher D, Puig M, Tonelli LH, Wang V, Ito S, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides protect newborn mice from a lethal challenge with the neurotropic Tacaribe arenavirus. J Immunol. 2006 Apr 15;176(8):4940–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wynn JL, Scumpia PO, Delano MJ, O’Malley KA, Ungaro R, Abouhamze A, et al. Increased mortality and altered immunity in neonatal sepsis produced by generalized peritonitis. Shock. 2007 Dec;28(6):675–83. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3180556d09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Henneke P, Berner R. Interaction of neonatal phagocytes with group B streptococcus: recognition and response. Infect Immun. 2006 Jun;74(6):3085–95. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01551-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Carr R. Neutrophil production and function in newborn infants. Br J Haematol. 2000 Jul;110(1):18–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Higgins RD, Fanaroff AA, Duara S, Goldberg R, et al. Very low birth weight preterm infants with early onset neonatal sepsis: the predominance of gram-negative infections continues in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 2002–2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005 Jul;24(7):635–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168749.82105.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pineles BL, Erez O, et al. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Sep;50(3):652–83. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31811ebef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tsuji S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Azuma I, Hayashi A, et al. Maturation of human dendritic cells by cell wall skeleton of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin: involvement of toll-like receptors. Infect Immun. 2000 Dec;68(12):6883–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6883-6890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sanghavi SK, Shankarappa R, Reinhart TA. Genetic analysis of Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain sequences from rhesus macaque Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 1–10 reveals high homology to human TLR/TIR sequences. Immunogenetics. 2004 Dec;56(9):667–74. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]