Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risks of human colorectal cancer. In this study, the effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) on chemically-induced colitis in a mouse model were evaluated. Chemical composition of SME was determined by HPLC analysis. A/J mice received a single injection of AOM 7.5 mg/kg. After one week, these mice received 2.5% DSS for 8 days, or DSS plus SME (25 or 50 mg/kg). DSS-induced colitis was scored with the disease activity index (DAI). Body weight and colon length were also measured. The severity of inflammatory lesions was further evaluated by colon tissue histological assessment. HPLC assay showed that the major constituents in the tested SME were danshensu, protocatechuic aldehyde, salvianolic acid D and salvianolic acid B. In the model group, the DAI score reached its highest level on Day 8, while the SME group on both doses showed a significantly reduced DAI score (both P < 0.01). As an objective index of the severity of inflammation, colon length was reduced significantly from the vehicle group to model group. Treatment with 25 and 50 mg/kg of SME inhibited the reduction of colon in a dose-related manner (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). SME groups also significantly reduced weight reduction (P < 0.05). Colitis histological data supported the pharmacological observations. Thus, Salvia miltiorrhiza could be a promising candidate in preventing and treating colitis and in reducing the risks of inflammation-associated colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Salvia miltiorrhiza, Dan Shen, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Dextran Sodium Sulfate, DSS, Azoxymethane, AOM, Colitis, Carcinogenesis, Colorectal Cancer, Chemoprevention

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common form of cancer in the United States and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the West (NCI, 2012b). In fact, 1 in 18 American men and 1 in 20 women are at risk for developing invasive CRC in their lifetime (NCI, 2012a). It has been estimated that the economic impact of CRC is up to $8.4 billion or over 10% of all cancer treatment expenditures. In Chinese patients undergoing screening colonoscopy, large and proximal serrated polyps were detected in 2.3% and 7.2%, respectively, and the individuals with these polyps have a higher risk of synchronous advanced neoplasia (Leung et al., 2012). Therefore, it is a particularly relevant public health task worldwide to develop more effective evidence-based botanical intervention for patients diagnosed with CRC (Randhawa and Alghamdi, 2011; Wang et al., 2012a).

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Dan Shen or

in Chinese) or S. miltiorrhiza is a perennial herbal plant of the Labiatae family. This herb can be found throughout most of China, and it is mainly produced in Jiangsu, Anhui, Hebei, Shanxi and Sichuan provinces. Based on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) descriptions, S. miltiorrhiza root is bitter in flavor, slightly cold in nature, and mainly manifests its therapeutic actions in the heart, pericardium and liver meridians (Chen and Chen, 2004; Zhou et al., 2005). The herb activates and nourishes blood, removes blood stasis, regulates menstruation and calms the spirit, and is used for the treatment of coronary heart disease and other cardiovascular disorders, blood circulation diseases, menstrual disorders including menostasis, and hepatitis (Chan et al., 2012; Wu and Wang, 2012).

in Chinese) or S. miltiorrhiza is a perennial herbal plant of the Labiatae family. This herb can be found throughout most of China, and it is mainly produced in Jiangsu, Anhui, Hebei, Shanxi and Sichuan provinces. Based on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) descriptions, S. miltiorrhiza root is bitter in flavor, slightly cold in nature, and mainly manifests its therapeutic actions in the heart, pericardium and liver meridians (Chen and Chen, 2004; Zhou et al., 2005). The herb activates and nourishes blood, removes blood stasis, regulates menstruation and calms the spirit, and is used for the treatment of coronary heart disease and other cardiovascular disorders, blood circulation diseases, menstrual disorders including menostasis, and hepatitis (Chan et al., 2012; Wu and Wang, 2012).

Recent pharmacological studies reported that S. miltiorrhiza reduced small intestine inflammation and pancreatitis (Xiping et al., 2010). The lipid-soluble extract of the herb showed significant inhibitory effects on drug-induced inflammatory mediators, and these effects were supported by in vivo observation (Li et al., 2012). S. miltiorrhiza and its constituents also attenuated the inflammatory response and apoptosis after rat spinal cord injury (Yin et al., 2012).

The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, is associated with colonic mucosal ulceration, shortening of the colon, diarrhea, blood in the feces, and weight loss (Fiocchi, 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Kohn and Meddi, 2012). It is well known that chronic inflammation in the colon can lead to cancer in humans (Hanauer, 1996; Geier et al., 2007). However, to date, the effects of S. miltiorrhiza on acute experimental colitis have not been reported. In addition, only limited studies used its water-soluble extract, which represents a different group of chemical constituents. In this study, we used a water-soluble extract of S. miltiorrhiza, and evaluated its effects on colon inflammation induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

HPLC grade acetonitrile was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Formic acid (purity no less than 96%) was obtained from Tedia (Fairfield, OH). Milli Q water was supplied by a water purification system (US Filter, Palm Desert, CA). Azoxymethane (AOM) was obtained from the NCI Chemical Carcinogen Reference Standard Repository, Midwest Research (Kansas City, MO). Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS, molecular weight of 36,000–50,000 Da) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Hemoccult Sensa test strips were obtained from Beckman Coulter, Inc. (Brea, CA).

Herbal Extract and Standards

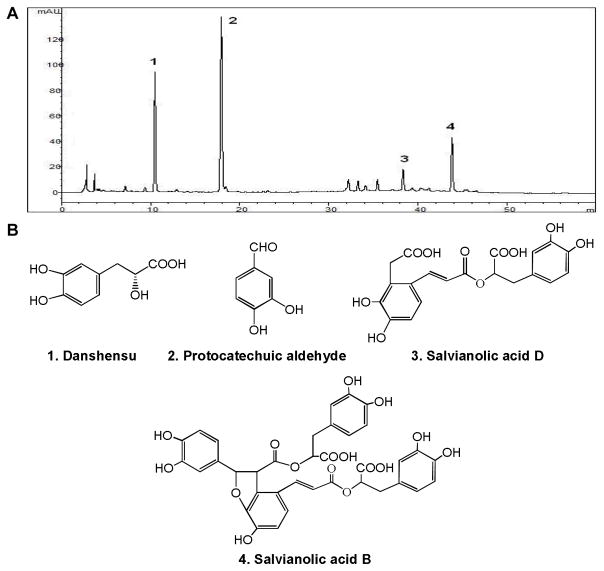

S. miltiorrhiza extract (SME), lyophilized powder for injection (lot number 110546, permission code of Chinese State Food and Drug Administration: Z10970093), was purchased from the Harbin Pharm Group Co. Ltd. (Harbin, Heilongjiang, China). Chemical standards of danshensu, protocatechuic aldehyde, salvianolic acid D and salvianolic acid B (Fig. 1B) were purchased from Shanghai Tauto Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The purities of the standards were determined to be higher than 98% by high performance liquid chromatography.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) and chemical structures of identified representative constituents in SME. (A) HPLC chromatogram of SME recorded at 280 nm. (B) Chemical structures of four identified compounds.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis

The HPLC system was an Agilent 1100 instrument with a quaternary pump, an automatic injector, and a photodiode array detector. The separation was carried out on a Zobax Extend C-18 column (5μ, 4.6 mm × 250 mm). For the HPLC analysis, a 10-μL sample was injected into the column and eluted at room temperature with a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. For the mobile phase, 0.2% formic acid in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) were used. The gradient program was optimized as the following: 0–10 min, 5–18% B and 95–82% A; 10–20 min, 18–20% B; 20–40 min, 20–25% B; 40–50 min, 25–35% B; 50–60 min, 35–70% B; and 60–70 min, 70–100% B. The detection wavelength was set to 280 nm. The SME stock solution (6 mg/ml) was prepared by dissolving SME powder in water and was stored at −70°C. Before analysis, the stock solution was diluted to 0.6 mg/ml with water, filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter and then centrifuged at 13,000 g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant of the SME solution was injected into the HPLC system for analysis.

Animal Treatment

The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. All experiments were carried out in male A/J mice, 6–8 weeks old, weighing between 18 and 22 g, obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were caged under a controlled room temperature, humidity and light (12/12 h light/dark cycle) and allowed unrestricted access to standard mouse chow and tap water. The mice were allowed to acclimate to these conditions for at least 7 days before inclusion in the experiments.

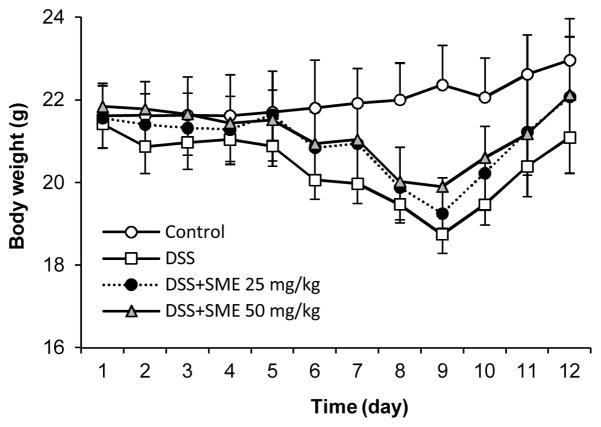

The experimental protocol is shown in Figure 1A. There were 4 experimental groups (n = 8 per group). Group 1 is the vehicle control. Animals in Group 2 (model), Group 3 (low-dose), and Group 4 (high dose) initially received a single intraperitoneal injection of AOM (7.5 mg/kg). One week after the AOM injection (set as Day 1), these animals started to receive 2.5% DSS in drinking water for consecutive 8 days. Animals in Group 3 (low-dose group) and Group 4 (high-dose group) also received SME 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection every other day, respectively. During treatment, animal body weight was measured daily. Animals were sacrificed on Day 12, entire colon (cecum to anus) was removed and colon length was measured from the ileocecal junction to the anus. Colon tissue samples were collected for additional observations.

Disease Activity Index

DSS induced colitis was scored as the Disease Activity Index (DAI) as described previously (Cooper et al., 1993). The DAI score was obtained based on weight loss, stool consistency change, and bleeding in stool (Table 1). The minimal score was 0 and the maximal score was 4. The animals were scored for the DAI at the same time of each day, blind to the treatment received.

Table 1.

Scoring System for Disease Activity Index (DAI).

| Score | Weight Loss | Stool Consistency | Blood in Stool |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None | None |

| 1 | 1–5% | --- | Trace |

| 2 | 5–10% | Loose stool | Hemoccul + |

| 3 | 10–20% | --- | Hemoccul ++ |

| 4 | >20% | Diarrhea | Gross bleeding |

The DAI was the combined scores of weight loss, stool consistency and bleeding divided by 3. Stool bleeding score: trace, scarcely blue; hemoccul +, blue easily detected; hemoccul ++, strongly blue. Acute clinical symptoms are diarrhea and/or grossly bloody stools.

Histological Assessment

Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were serially sectioned, and one section from each mouse was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained sections were subsequently examined for histopathological changes by a gastrointestinal pathologist.

Histology score was determined by multiplying the percent involvement for each of the three following histologic features by the percent area of involvement (Jin et al., 2010): inflammation severity (from 0, none to 3, severe), inflammation extent (from 0, to 3, transmural), crypt damage (from 0, none to 4, crypts and surface epithelium lost), and percent area involvement (from 0, 0% to 4, 76–100%). The minimal score was 0 and the maximal score was 40.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard error (S.E.). Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures and Student’s t-test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

HPLC Analysis of SME

The HPLC-UV fingerprint of SME is shown in Figure 1A. The constituents in SME were well separated under the established HPLC condition. From the chromatogram of SME, four main peaks were observed. After comparing their retention times and UV spectra with standards, they were identified as danshensu, protocatechuic aldehyde, salvianolic acid D and salvianolic acid B (Fig. 1B). Based on their peak area, the major constituents in SME are the former two compounds.

SME Ameliorates DSS-Induced Colitis

After DSS treatments, animals showed apparent diarrhea and rectal bleeding starting from Day 5 in the model group. As the treatment continued, presence and development of inflammation were clearly demonstrated. The disease severity, scored by disease activity index (DAI) reached highest level on Day 8 (Fig. 2). Figure 2(B) shows the effects of SME on the reduction of the DAI score in a dose-related manner (P < 0.01). This suppression of the colitis was not only evident during DSS treatment, but also obvious several days after the cessation of its administration, suggesting that SME significantly promoted the recovery from the colitis.

Figure 2.

Effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) on DSS-induced colitis. (A) Experimental protocol. (B) SME ameliorates the colitis, expressed as Disease Activity Index (DAI). Data from the control group are all zeros from Day 1 to Day 12 (no shown). The dose-related effects of SME are observed (P < 0.05).

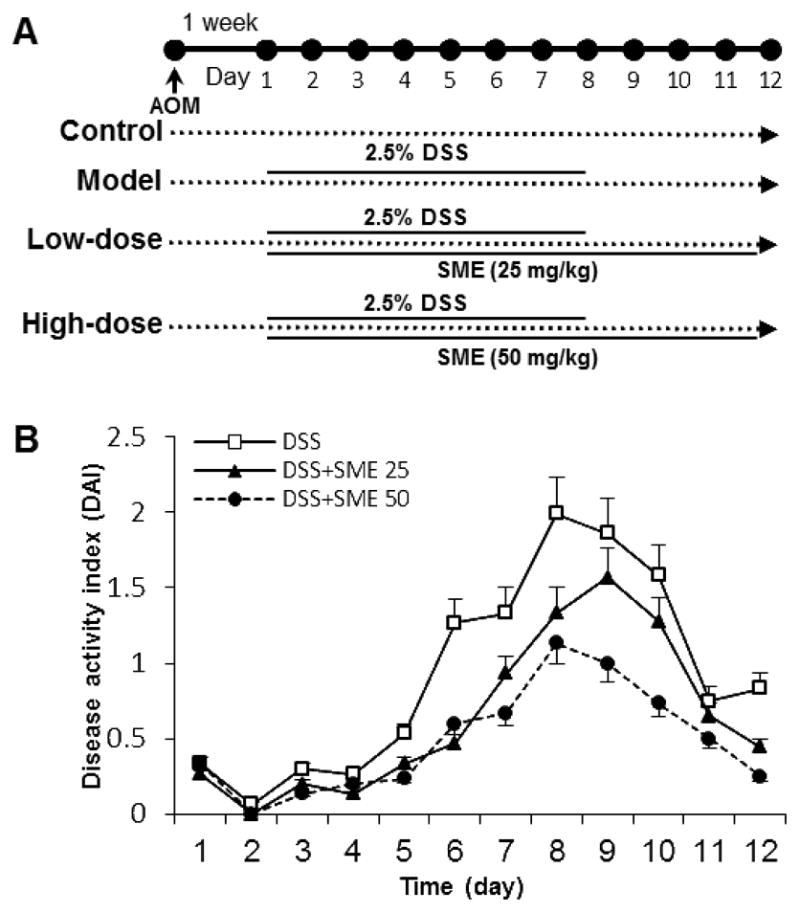

Effect of SME on DSS-Induced Colon Length Change

Colon length, as an objective measure of the severity of inflammation, was measured (Fig. 3). The control group animal had an average colon length of 8.6 ± 0.5 cm. The DSS treatment led to a very significant reduction of colon length, and the length in the model group animals was reduced to 5.5 ± 0.6 cm (P < 0.01 compared to control). Treatment with a low-dose and high-dose of SME inhibited the reduction of the colon in a dose-related manner (6.7 ± 0.6 and 7.8 ± 0.5 cm, both P < 0.01 compared to the model group).

Figure 3.

Mouse colon length changes in different groups. (A) Colon representative photographic images. (B) For model group, DSS treatment very significant reduces the colon length from control group (#, P < 0.01 compared to the control group). Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) low-dose and high-dose treatment significantly decreased the colon length reduction (*, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01 compared to the model group, respectively). SME 25, SME 25 mg/kg; SME 50, SME 50 mg/kg.

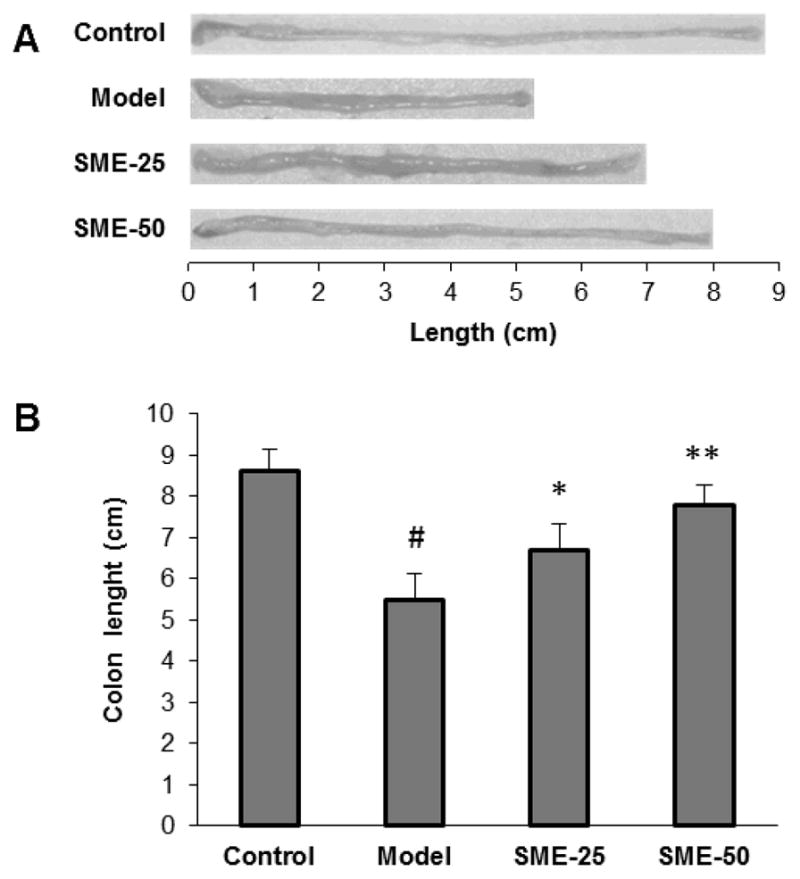

Effect of SME on Body Weight Changes

Figure 4 showed body weight changes in different experiment groups. Compared to control with a slow gain of the weight, the model group had significant weight reduction starting from Day 6. This reduced weight continued up to Day 9, one day after cessation of the DSS. However, both the low-dose and high-dose SME groups significantly reduced the body weight reduction (both P < 0.05 compared to the model group).

Figure 4.

Effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) on mouse body weight changes. While the model group shows significant weight reduction from Day 6, SME low-dose (25 mg/kg) and high-dose (50 mg/kg) treatment significantly reduced the DSS-induced weight reduction (both P < 0.05 compared to the model group).

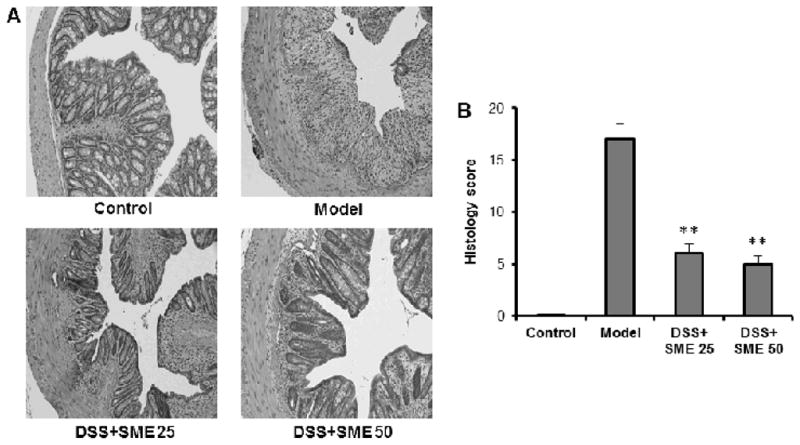

Effect of SME on Colon Histopathology Changes

From H&E staining of histological sections, colon tissue from model animals showed increasingly severe inflammatory lesions extensively throughout: significant and complete loss of crypts; surface erosion with exuberant inflammatory exudate; patchy re-epithelization; lamina propria fibrosis with acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate; and submucosa edema and mixed inflammatory cell infiltration. For mice treated with SME, there was a significant reduction in colon inflammation. This reduction is particularly evident in the high-dose group: serosa colon tissue had mild inflammation, mucosa had tightly packed glands with a normal amount of goblet cells; lamina propria showed patchy neutrophilic infiltrate which extended into the submucosa; and normal serosa observed. Figure 5 shows representative H&E staining histological sections (A), and overall histology scores are provided (B).

Figure 5.

Effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract (SME) on the histological characterization in DSS-induced mouse colitis. (A) shows representative H&E staining histological sections of control, DSS only, DSS plus low-dose SME, and DSS plus high-dose SME. (B) shows the overall histology scores in these different groups (**, P < 0.01 compared to the model group). SME 25, SME 25 mg/kg; SME 50, SME 50 mg/kg.

Discussion

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is under the guidance of its unique theory – a theory that is deeply influenced by both ancient philosophy and accumulated clinical experience. Chinese herbal medicine is a major component of TCM, and has played a critical role in the promotion of health, prevention of disease, and treatment of illnesses for Chinese people for several thousand years (Wang et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011). S. miltiorrhiza is a very commonly used Chinese herbal medicine, and it has a strategic position in TCM. The herb is mostly used for cardiovascular illness since it promotes circulation, removes blood stasis, nourishes and tranquilizes the blood (Bensky et al., 2004; Chen and Chen, 2004; Liu et al., 2011). Modern biomedical studies have shown that constituents of S. miltiorrhiza could be beneficial in intervening against cardiovascular disorders (Chan et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2011).

Compared to the cardiovascular studies of S. miltiorrhiza, an understating of its role in inflammation conditions is limited, while gastrointestinal inflammation is largely unexplored. Interestingly, only one study reported that the water-soluble extract of the herb, not other constituents, possessed anti-inflammatory properties in vitro and investigated its mechanism of action related to lipopolysaccharide, a bacterial product with a high content in the intestinal lumen. An in vitro kinase assay showed that the water-soluble extract directly inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced IκB kinase activity in IEC-18 cells. The extract blocked the lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB signaling pathway by targeting the IKK complex in intestinal epithelial cells (Kim et al., 2005). Modulation of bacterial product-mediated NF-κB signaling by the water-soluble extract could represent a strategy towards the prevention and treatment of intestinal inflammation. In this study, we used a water-soluble extract of S. miltiorrhiza to observe its effects on colon inflammation in a DSS-induced colitis mouse model.

S. miltiorrhiza contains both hydrophobic and hydrophilic compounds. Previous phytochemical and biological studies were often focused on the hydrophobic compounds. More than 30 diterpene compounds have been isolated and identified from the hydrophobic fraction, such as tanshinones (including tanshinone I, IIA, IIB, cryptotanshinone) and related compounds. The antiproliferative potential of many natural tanshinones and their synthetic analogs on different cancer cell lines has been routinely evaluated with possible mechanisms of actions (Wang et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2011). Investigations on hydrophilic compounds, however, are very limited to date. The major constituents of hydrophilic extract include water-soluble phenolic acids and tanshinones. In this study, we evaluated the effects of the hydrophilic extract of S. miltiorrhiza on AOM/DSS-induced colitis in a mouse model. It would be interesting to compare pharmacological effects between hydrophobic and hydrophilic components in the same experimental setting. Nonetheless, the hydrophilic extract of S. miltiorrhiza showed satisfactory effect in our study.

In summary, we showed that, in a dose-related manner, SME inhibited DSS-induced colotis, resulting in an overall attenuation of inflammation DAI, including colon length and body weight changes. The effects of the herb were further supported by histological characterization in mouse acute colitis. TCM has been practiced for thousands of years based on clinical experience. It is necessary to integrate existing TCM knowledge of diseases with modern biomedical technologies (Wang et al., 2012b), and explore the mechanisms of action of the observed pharmacological effects. Future controlled clinical trials of Salvia miltiorrhiza on IBD symptoms are also warranted to evaluate the candidacy of the herb in the TCM-based CRC prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCCAM grants P01 AT004418 and K01 AT005362, and the National Science Foundation of China (No. 30973884).

References

- Bensky D, Clavey S, Stoger E, Gamble A. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica. 3. Eastland Press; Seattle: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Chen YC, Lin LJ, Cheng TH, Anzai K, Chen YH, Liu ZM, Lin JG, Hong HJ. Tanshinone IIA attenuates H(2)O(2)-induced injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40:1307–1319. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Liu JC, Lin LJ, Chen PY, Cheng TH, Lin JG, Hong HJ. Tanshinone IIA inhibits angiotensin II-induced cell proliferation in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:381–394. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11008890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chen T. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. Art of Medicine Press, City of Industry; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest. 1993;69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH. Biosynthesis, total syntheses, and antitumor activity of tanshinones and their analogs as potential therapeutic agents. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28:529–542. doi: 10.1039/c0np00035c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier MS, Butler RN, Howarth GS. Inflammatory bowel disease: current insights into pathogenesis and new therapeutic options; probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:841–848. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Wang XY, Zhou WY, Li J, Wang J, Guo LP. Cerebral protection of salvianolic acid A by the inhibition of granulocyte adherence. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:111–120. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11008683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Hofseth AB, Cui X, Windust AJ, Poudyal D, Chumanevich AA, Matesic LE, Singh NP, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS, Hofseth LJ. American ginseng suppresses colitis through p53-mediated apoptosis of inflammatory cells. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:339–347. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Narula AS, Jobin C. Salvia miltiorrhiza water-soluble extract, but not its constituent salvianolic acid B, abrogates LPS-induced NF-kappaB signalling in intestinal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kim KW, Kim DS, Kim MC, Jeon YD, Kim SG, Jung HJ, Jang HJ, Lee BC, Chung WS, Hong SH, Chung SH, Um JY. The protective effect of Cassia obtusifolia on DSS-induced colitis. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:565–577. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11009032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Meddi P. How to manage IBD in patients with infections or malignancies? Dig Dis. 2012;30:420–424. doi: 10.1159/000338145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WK, Tang V, Lui PC. Detection rates of proximal or large serrated polyps in Chinese patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhang L, Cai RL, Gao Y, Qi Y. Lipid-soluble extracts from Salvia miltiorrhiza inhibit production of LPS-induced inflammatory mediators via NF-kappaB modulation in RAW 264.7 cells and perform antiinflammatory effects in vivo. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1195–1204. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang Y, Ma C, Zhang L, Wu W, Guan S, Yang M, Wang J, Jiang B, Guo DA. Proteomic assessment of tanshinone IIA sodium sulfonate on doxorubicin induced nephropathy. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:395–409. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11008907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI. [Accessed on December 16, 2012];Colon and Rectal Cancer. 2012a http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/colon-and-rectal.

- NCI. [Accessed on December 18, 2012];Common Cancer Types. 2012b http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers.

- Randhawa MA, Alghamdi MS. Anticancer activity of Nigella sativa (black seed) - a review. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:1075–1091. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X1100941X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Calway T, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines as adjuvants for cancer therapeutics. Am J Chin Med. 2012a;40:657–669. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Mehendale SR, Calway T, Yuan CS. Botanical flavonoids on coronary heart disease. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:661–671. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X1100910X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH. New developments in the chemistry and biology of the bioactive constituents of Tanshen. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:133–148. doi: 10.1002/med.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang A, Sun H, Wang P. Systems biology technologies enable personalized traditional chinese medicine: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med. 2012b;40:1109–1122. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WY, Wang YP. Pharmacological actions and therapeutic applications of Salvia miltiorrhiza depside salt and its active components. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:1119–1130. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiping Z, Yan P, Xinmei H, Guanghua F, Meili M, Jie N, Fangjie Z. Effects of dexamethasone and Salvia miltiorrhizae on the small intestine and immune organs of rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Inflammation. 2010;33:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Chen X, Zhong Z, Chen L, Wang Y. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides: immunomodulation and potential anti-tumor activities. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:15–27. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11008610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Yin Y, Cao FL, Chen YF, Peng Y, Hou WG, Sun SK, Luo ZJ. Tanshinone IIA attenuates the inflammatory response and apoptosis after traumatic injury of the spinal cord in adult rats. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MS. Danshen: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1345–1359. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]