Abstract

Context

Scutellaria baicalensis is one of the most commonly used medicinal herbs, especially in traditional Chinese medicine. However, compared to many pharmacological studies of this botanical, much less attention has been paid to the quality control of the herb’s pretreatment prior to extract preparation, an issue that may affect therapeutic outcomes.

Objective

The current study was designed to evaluate whether different pretreatment conditions change the contents of its four major flavonoids in the herb, i.e., two glycosides (baicalin and wogonoside) and two aglycons (baicalein and wogonin).

Materials and methods

An HPLC assay was used to quantify the contents of these four flavonoids. The composition changes of four flavonoids by different pretreatment conditions including solvent, treatment time, temperature, pH value, and herb/solvent ratio were evaluated.

Results

After selection of the first order time-curve kinetics, our data showed that at 50°C, 1:5 herb/water (in w/v) ratio and pH 6.67 yielded an optimal conversion rate from flavonoid glycosides to their aglycons. In this optimized condition, the contents of baicalin and wogonoside were decreased to 1/70 and 1/13, while baicalein and wogonin were increased 3.5 and 3.1 folds, respectively, compared to untreated herb.

Discussion and conclusion

The markedly variable conversion rates by different pretreatment conditions complicated the quality control of this herb, mainly due to the high amount of endogenous enzymes of S. baicalensis. Optimal pretreatment conditions obtained from this study could be used obtain the highest level of desired constituents to achieve better pharmacological effects.

Keywords: Herbal medicine, Traditional Chinese medicine, Endogenous enzyme, beta-D-glucuronidase, beta-D-glucosidase, Pretreatment, Quality control

Introduction

Chinese herbal medicine, the major component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), has played a vital role in the prevention and treatment of different diseases for Chinese people for several thousand years (Liu et al., 2011; Xutian et al., 2012). Prescribed by Chinese medicine practitioners, TCM herbal formulations are formed based on TCM theory. Each TCM formulation often consists of several to a dozen of different Chinese medicinal herbs. As Chinese herbal medicine has become more and more popular around the world, research into these botanicals has increased as well (Wang et al., 2012). Indeed, many of these studies have mainly paid attention to the effectiveness of the Chinese herbal treatment.

Preparation of Chinese medicinal herbs in a given formulation is usually based on empirical practice. The preparation procedures often are as follows: (1) Identify and clean the herbs for the formulation. (2) As pretreatment, soak the mixed herbs in pure water for a certain period of time (usually recommended for 30 min). (3) Boil or decoct the mixed herbs in the water for a certain period of time (usually recommended for 15–20 min), to obtain the final TCM medicine or herbal tea. The latter is also called an herbal water extraction in botanical studies. However, compared to numerous herbal efficacy investigations, much less attention has been paid to the quality control of extraction pretreatment of TCM herbal formulations (Wang et al., 2012).

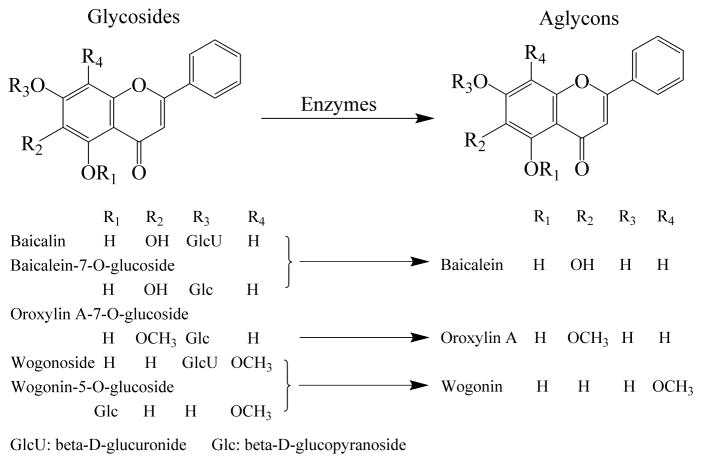

The dried root of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Labiatae) is one of the most widely used herbal medicines in China, and this herb has been included as an important ingredient in many TCM herbal formulations. Studies have shown that S. baicalensis possesses effects in treating inflammation, protecting cardiac function, reducing cholesterol level and blood pressure, and has anti-HIV and anti-cancer potentials (Awad et al., 2003; Bergeron et al., 2005; Bochorakova et al., 2003; Chou et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2001). These medicinal effects are largely due to the four flavonoids of the herb: baicalin, baicalein, wogonoside and wogonin, especial the two aglycons (baicalein and wogonin) (Awad et al., 2003; Makino et al., 2008). Because of the endogenous enzymes in the S. baicalensis, two glycosides (baicalin and wogonoside) can be converted to their corresponding aglycons (baicalein and wogonin) (Ikegami et al., 1995; Li et al., 2009; Sasaki et al., 2000) (Figure 1). In this study, we selected S. baicalensis to evaluate whether different pretreatment conditions of the herb would change these four flavonoid contents during extraction, ultimately affect the quality control of the herb preparation and its medicinal activities.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the major flavonoids in S. baicalensis during endogenous enzymatic conversion from glycosides to aglycons. These enzymes likely are beta-D-glucuronidase, beta-D-glucosidase and other beta-D-glycosidases. The lower portion of the figures listed the conversion of five glycosides to three aglycons.

Materials and methods

Plant material

S. baicalensis root was obtained from Tianyi Drugstore Company (Huai’an, China), and was identified by Dr. Chunhao Yu. The voucher samples were identified by Associate Professor Haijiang Zhang and deposited at the Group of BioTCM and Biocatalysis, Faculty of Life Science & Chemical Engineering, Huaiyin Institute of Technology. Dried S. baicalensis roots were ground with a blade-mill (FW135 Medicine Mill, Nanjing, China) to obtain a relatively homogenous herbal powder, and then sieved through a 10-mesh screen. The powder was dried in a desiccator with silica gel at ambient temperature until reaching a constant weight.

Chemicals and reagents

Four flavonoid standards, baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein and wogonin, were obtained from the National Institute for Control of Pharmaceuticals and Biological Products (Beijing, China). These four standards were at least 95% pure confirmed by HPLC assay. HPLC grade acetonitrile and glacial acetic acid were obtained from Tedia Company (Fairfield, OH). The water was supplied by a Milli-Q Water Purification System (Millipore, MA). All reagents were of biochemical-reagent grade.

HPLC chromatography analysis

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was performed on a Waters Alliance 2695 instrument coupled with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector. The HPLC analysis was carried out on an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 3.5 μm) attached with an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 guard column (4.6 mm × 12.5 mm, 5μm) in a column thermostated compartment set at 30°C, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min, with the following gradient: 0–50 min from 20% A linear to 42% A, 50–55 min linear to 50% A, 55–60 min washing with 50% A, 60–61 min linear back to 20% A, and 61–70 min continuous 20% A for equilibration (solvent A 100% acetonitrile; solvent B 99.5% H2O, 0.5% glacial acetic acid). A Waters 2996 photodiode array detector was used and set to scan from 200 to 400 nm. The injection volume was 10 μL. All tested solutions were filtered through a membrane filter (0.2 μm pore size). The content of the constituents was calculated using standard curves of four flavonoids. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Pretreatment of S. baicalensis

The herbal powder (1 g) was accurately weighted for 50 mL volumetric flasks. A certain volume of specific solvent (such as pure water, 75% ethanol or Britton-Robinson’s buffer solution when pH adjustment required) was added to each flask. The flasks were immediately put into a thermostatic water bath shaker (130 rpm) at the intended temperature (such as 5, 25, 37, 50 or 90°C) for a period of pretreatment time (0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 120, and 240 min).

Extraction of S. baicalensis

After the pretreatment, absolute ethanol was added to the pretreated solution to adjust to a final ethanol concentration of 75% (v/v). The solution was ultrasonically extracted in an ultrasonic bath (Kunshan Ultrasonic Instrument Co., China) at 25°C for 30 min. Fifty milliliters of the total volume was adjusted with 75% ethanol prior to extract filtration. The filtrate was used for HPLC analysis.

Kinetics of treatment time-curves

To obtain reliable curves for the four measured flavonoids in S. baicalensis, we used the empirical model and three integral equations (Bansal et al., 2009; Holtzapple et al., 1984) as follows:

Empirical model

For glycosides, such as baicalin and wogonoside:

Where C0 is the initial content of glycosides in S. baicalensis (μmol/g), Cmax is the theoretical maximum transformed content (μmol/g) and t0.5 is the time to transformation 0.5Cmax.

For aglycons, such as baicalein and wogonin:

Where C0 is the initial content of aglycons in S. baicalensis (μmol/g), Cmax is the theoretical maximum formed content (μmol/g) and t0.5 is the time to form 0.5Cmax.

Zero-order kinetics

For glycosides, such as baicalin and wogonoside:

Where C0 is the initial content of glycosides in S. baicalensis (μmol/g) and k0 is the zero-order rate constant (μmol/g/min) of glycosides.

For aglycons, such as baicalein and wogonin:

Where C0 is the initial content of aglycons in S. baicalensis (μmol/g) and k0 is the zero-order rate constant (μmol/g/min) of aglycons.

First-order kinetics

For glycosides, such as baicalin and wogonoside:

For aglycons, such as baicalein and wogonin:

Where is the initial content of glycosides in S. baicalensis (μmol/g), is the initial content of aglycons in S. baicalensis (μmol/g) and k1 is the first-order rate constant (1/min).

Second-order kinetics

For glycosides, such as baicalin and wogonoside:

For aglycons, such as baicalein and wogonin:

Where, is the initial content of glycosides in S. baicalensis (μmol/g), is the initial content of aglycons in S. baicalensis (μmol/g) and k2 is the second-order rate constant (g/μmol/min).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, CA) was used to evaluate the reliable time-curves for the measured flavonoid time points. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The flavonoid content data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures and Student’s t-test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

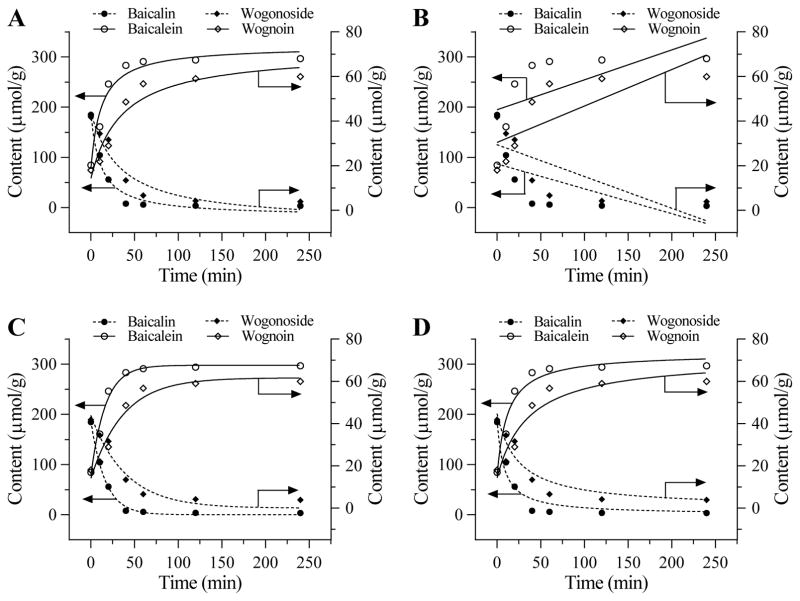

Selection of kinetics for the time-curves and pretreatment length

Four kinetic equations used for the treatment time-curves are shown in Figure 2. First order kinetics were chosen since they show the most reliable time-curves based on the obtained values of adjusted R2 and probability obtained (Table 1). In addition, 60 min pretreatment time was adequate to use from Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Four kinetics used to evaluate the time-curves of the measured four flavonoids in S. baicalensis during pure water pretreatment. (A) Empirical equation. (B) Zero-order kinetics. (C) First-order kinetics. (D) Second-order kinetics. Based on Table 1 data, the first order kinetics was chosen for Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6 observations.

Table 1.

Four kinetic equations used in Figure 2. The first order kinetics was chosen since it showed the most reliable pretreatment time-curves based on the values of adjusted R2 and probability obtained.

| Kinetics | Equation | Adjusted R2 | Probability (>F) | t0.5 (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical model | |||||

| Baicalin |

|

0.9586 | 6.14E-4 | 11.16 | |

| Wogonoside |

|

0.9012 | 1.30E-3 | 33.13 | |

| Baicalein |

|

0.9380 | 3.45E-5 | 12.08 | |

| Wogonin |

|

0.8884 | 2.46E-4 | 35.67 | |

| Zero order | |||||

| Baicalin |

|

0.23976 | 1.00E-1 | 86.86 | |

| Wogonoside |

|

0.48099 | 1.50E-2 | 104.96 | |

| Baicalein |

|

0.25019 | 1.50E-3 | ||

| Wogonin |

|

0.48768 | 1.60E-3 | ||

| First order | |||||

| Baicalin |

|

0.9955 | 4.61E-7 | 11.32 | |

| Wogonoside |

|

0.9497 | 5.57E-5 | 27.69 | |

| Baicalein |

|

0.9796 | 3.74E-6 | ||

| Wogonin |

|

0.9368 | 7.99E-5 | ||

| Second order | |||||

| Baicalin |

|

0.9448 | 2.36E-4 | 8.03 | |

| Wogonoside |

|

0.9005 | 2.99E-4 | 24.01 | |

| Baicalein |

|

0.9380 | 3.45E-5 | ||

| Wogonin |

|

0.8884 | 2.46E-4 | ||

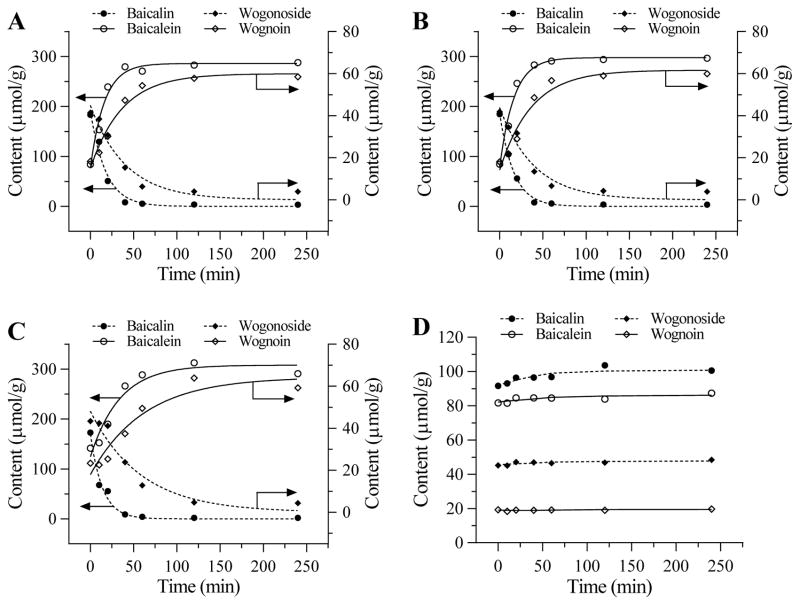

Effects of different initial temperature and solvent on the four flavonoid contents in S. baicalensis

Figure 3(A–C) shows effects of using three different water temperatures, 25°C, 50°C, or 90°C, for initial soaking. Data showed that 50°C warm water is best; thus, we selected 50°C warm water for initial soaking for the pretreatment. Figure 3(D) shows that at 25°C for initial soaking but using 75% ethanol for pretreatment, the conversion rate is limited.

Figure 3.

Effects of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different initial temperature and solvent on the four flavonoid content changes at 50°C. (A) Using 25°C water for initial soaking. (B) Using 50°C warm water for initial soaking. (C) Using 90°C hot water for initial soaking (D) Using 75% ethanol at 25°C for initial soaking.

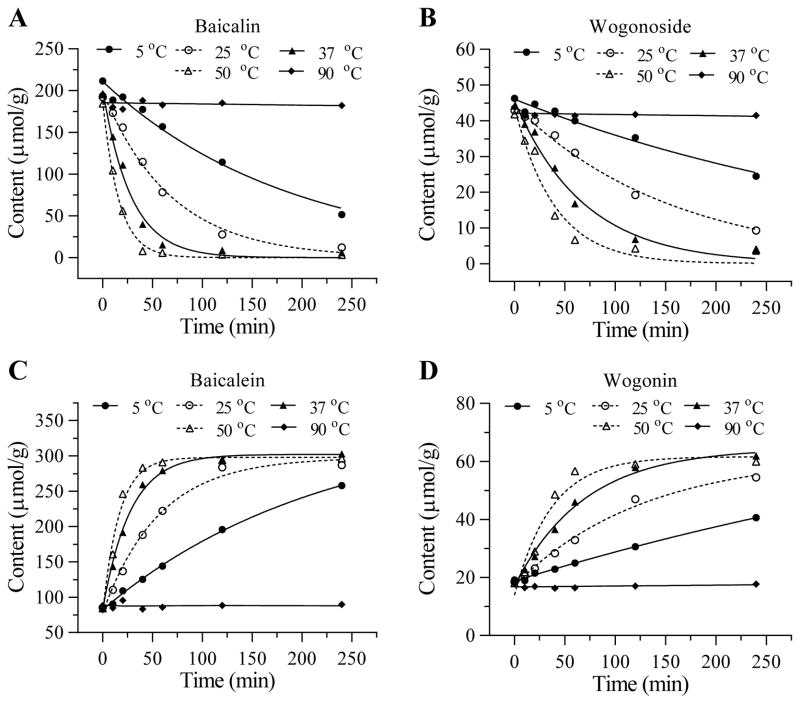

Effects of different temperatures in pretreatment of the four flavonoid contents

Figure 4 shows five different steady temperatures, 5°C, 25°C, 37°C, 50°C, or 90°C, used in pretreatment. Based on the decreases in the glycosides and increases in aglycons during the pretreatment, 50°C is the most suitable for pretreatment (P < 0.05 when data from 50°C were compared to that of 25°C for all four flavonoids).

Figure 4.

Effects of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different steady temperature on the four flavonoid content changes. Glycosides are shown in (A) baicalin and (B) wogonoside. Aglycons are shown in (C) baicalein and (D) wogonin.

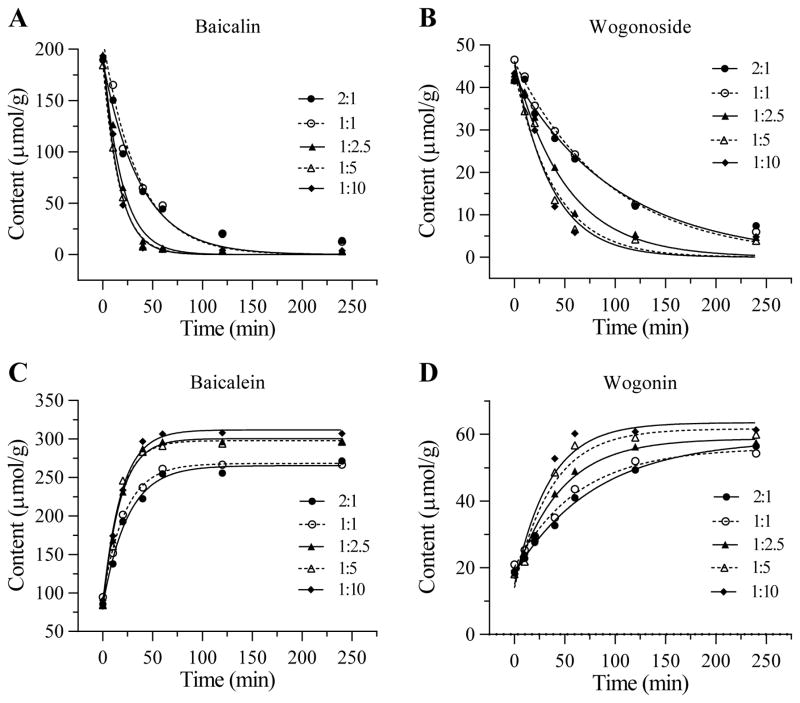

Effects of different herb/water ratio in pretreatment of the four flavonoid contents

The effect of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different herb/water (in w/v) ratios on the four flavonoid content changes is shown in Figure 5. Based on the magnitude of decrease in glycosides and increase in aglycons, the herb/water ratio in pretreatment should be 1:5 or 1:10. However, for practical preparation purposes, 1:5 was selected.

Figure 5.

Effects of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different herb/water (in w/v) ratio on four flavonoid content changes. Glycosides are shown in (A) baicalin and (B) wogonoside. Aglycons are shown in (C) baicalein and (D) wogonin.

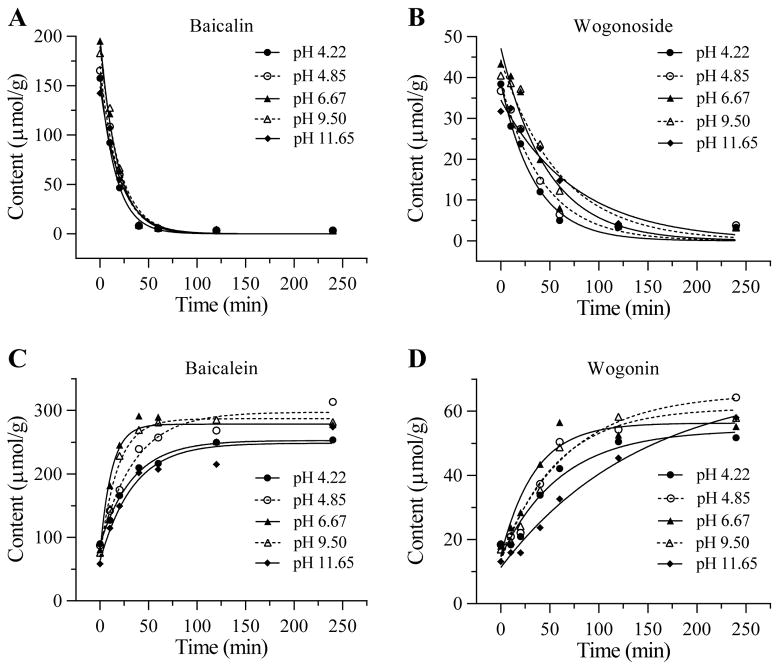

Effects of different pH values in pretreatment of the four flavonoid contents

The effect of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different pH values on the four flavonoid content changes is shown in Figure 6. Based on the magnitude of decrease in glycosides and increase in aglycons, a pH value of 6.67 should be satisfactory. In this optimized condition, for the four flavonoids baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein and wogonin, compared to untreated control (194.9, 43.3, 80.3 and 17.9 μM/g), after 4 h treatment, the contents were changed to 3.2, 3.3, 277.6 and 55.2 μM/g, respectively. The contents of baicalin and wogonoside were decreased to 1/70 and 1/13, while baicalein and wogonin were increased 3.5 and 3.1 folds compared to untreated herb.

Figure 6.

Effects of S. baicalensis pretreatment with different pH values on four flavonoid content changes. Glycosides are shown in (A) baicalin and (B) wogonoside. Aglycons are shown in (C) baicalein and (D) wogonin.

Discussion

In ancient classic TCM literatures such as Li Shizhen’s (1518–1593) Ben Cao Gang Mu written in the Ming Dynasty and Xu Lingtai’s (1693–1771) Yi Xue Yuan Liu Lun published in the Qing Dynasty, herbal pretreatment has been described as an important part of herbal medicine preparation. In recent years, studies have been performed on the factors that affect herbal effectiveness. Among them, pretreatment prior to decoction or extraction was a significant aspect, and these results were published in Chinese literature (Ren et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004; Yang and Wu, 2009). Evidently, inconsistent herbal pretreatment increases the difficultness of the quality control of TCM herbal formulations. In other words, inadequate herbal extraction pretreatment may not be likely to achieve a desired targeted outcome.

In this study, we evaluated different extraction pretreatments on the four flavonoid contents in S. baicalensis. This botanical was chosen in our study due to several reasons. Firstly, S. baicalensis is a very commonly used herbal medicine, and it often appears in TCM formulations. Secondly, many modern pharmacological investigations have studied this botanical due to its various therapeutic activities. Thirdly, S. baicalensis would be more susceptible to pretreatment condition changes compared to the other herbal medicines, since this herb is enriched by endogenous enzymes, such as beta-D-glucuronidase, beta-D-glucosidase, and possibly other enzymes like beta-D-glycosidases (Ikegami et al., 1995; Li et al., 2009; Sasaki et al., 2000). Changes in pretreatment conditions should thus be likely to induce obvious changes in the contents of the four flavonoids. As expected, our data showed marked differences in the flavonoid contents after different extraction pretreatments. Largely due to its active endogenous enzymatic actions during the pretreatment, the two glycosides noticeably converted to their corresponding aglycons.

Since pharmacological actions of these glycosides and aglycons varied, variable pretreatment outcomes could be seen in clinical practice. For example, baicalein and wogonin possessed anti-HIV and anti-cancer effects (Lin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2000). Optimal pretreatment of this herb should increase these effects. On the other hand, if the glycoside contents are responsible for a certain pharmacological activity, extended pretreatment of the herb is likely to reduce that activity.

Data from this study suggest that for a single botanical, such as S. baicalensis, changeable pretreatment conditions can induce unpredictable effects in clinical therapeutics. Furthermore, this pretreatment outcome is more complicated by using TCM herbal formulations, because a formulation often consists of several different medicinal herbs. Herbal quality control consists of several aspects (Cai et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011), and extraction pretreatment further complicated the quality control of TCM therapies.

In TCM, a single herb, such as ginseng, can be used in treatment as an herbal formula prescription (Xutian et al., 2012). It is also not unusual that modern herbal products only have one single botanical. Data from our study demonstrate that, when S. baicalensis is used as a single herb, optimal extraction preparation should be used to obtain the highest constituents that are related to the intended treatment.

Conclusion

Our data showed that different extraction pretreatments markedly changed the flavonoid contents of S. baicalensis. This obvious change was mainly attributed to the high amount of endogenous enzymes in the herb, which likely affect the quality control of this TCM herbal formulation. However, when preparing a single herbal product, optimal pretreatment conditions obtained from this study could be considered to obtain highest level of desired constituents to achieve better treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCCAM grants K01 AT005362 and P01 AT 004418, the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2008194), Jiangsu Overseas Research & Training Program for University Prominent Young & Middle-aged Teachers and Presidents.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Awad R, Arnason JT, Trudeau V, Bergeron C, Budzinski JW, Foster BC, Merali Z. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (scutellaria lateriflora l.): A medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:640–649. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal P, Hall M, Realff MJ, Lee JH, Bommarius AS. Modeling cellulase kinetics on lignocellulosic substrates. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:833–848. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron C, Gafner S, Clausen E, Carrier DJ. Comparison of the chemical composition of extracts from scutellaria lateriflora using accelerated solvent extraction and supercritical fluid extraction versus standard hot water or 70% ethanol extraction. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3076–3080. doi: 10.1021/jf048408t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochorakova H, Paulova H, Slanina J, Musil P, Taborska E. Main flavonoids in the root of scutellaria baicalensis cultivated in europe and their comparative antiradical properties. Phytother Res. 2003;17:640–644. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CC, Yan MC, Xie H, Pan SL. Simultaneous determination of ten active components in 12 chinese piper species by hplc. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:1043–1060. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11009391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Chang LP, Li CY, Wong CS, Yang SP. The antiinflammatory and analgesic effects of baicalin in carrageenan-evoked thermal hyperalgesia. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1724–1729. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000087066.71572.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzapple MT, Caram HS, Humphrey AE. A comparison of two empirical models for the enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated poplar wood. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1984;26:936–941. doi: 10.1002/bit.260260818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami F, Matsunae K, Hisamitsu M, Kurihara T, Yamamoto T, Murakoshi I. Purification and properties of a plant beta-d-glucuronidase form scutellaria root. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:1531–1534. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Wang LS, Zou JM. Study on degradation of baicalin by endogenous enzymes in water extraction of scutellaria baicalensis. Chin Trad Herb Drugs. 2009;40:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lin CM, Chen YH, Ong JR, Ma HP, Shyu KG, Bai KJ. Functional role of wogonin in anti-angiogenesis. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40:415–427. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lawrence AJ, Liang JH. Traditional chinese medicine for treatment of alcoholism: From ancient to modern. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:1–13. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X11008609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino T, Hishida A, Goda Y, Mizukami H. Comparison of the major flavonoid content of s-baicalensis, s-lateriflora, and their commercial products. J Nat Med. 2008;62:294–299. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren CJ, Liu HW, Han T. How to properly prepared chinese medicine decoction. Jilin J Trad Chin Med. 2007;27:51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Taura F, Shoyama Y, Morimoto S. Molecular characterization of a novel beta-glucuronidase from scutellaria baicalensis georgi. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27466–27472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, He H, Wang X, Yuan CS. Trends in scientific publications of chinese medicine. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40:1099–1108. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Li XL, Wang QF, Mehendale SR, Yuan CS. Selective fraction of scutellaria baicalensis and its chemopreventive effects on mcf-7 human breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Mehendale SR, Calway T, Yuan CS. Botanical flavonoids on coronary heart disease. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:661–671. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X1100910X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Zhang RF, Wang YZ. Factors influencing pharmacodynamics of the chinese material medica decoction and the prospect of its development. Parm Care Res. 2004;4:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wu JA, Attele AS, Zhang L, Yuan CS. Anti-hiv activity of medicinal herbs: Usage and potential development. Am J Chin Med. 2001;29:69–81. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X01000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xutian S, Cao DY, Wozniak J, Junion J, Boisvert J. Comprehension of the unique characteristics of traditional chinese medicine. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40:231–244. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LL, Wu T. Study on the optimum soak time of ginsenosides with soak method. J Yunnan Univ Trad Chin Med. 2009;32:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Yue ST, Xue YX, Attele AS, Yuan CS. Effects of qian-kun-nin, a chinese herbal medicine formulation, on hiv positive subjects: A pilot study. Am J Chin Med. 2000;28:305–312. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X00000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]