Abstract

We investigated the choice of female crickets for a dynamic song parameter (chirp rate) on a walking compensator, and the underlying neuronal basis for the choice in the form of discharge differences in the pair of AN1-neurons driving the phonotactic steering behaviour. Our analysis reveals that decisions about chirp rate in a choice situation are made fast and reliably by female crickets. They steered towards the higher chirp rate after a delay of only 2.2–6 s, depending on the rate difference between the song alternatives. In this time period, the female experienced only one to two additional chirps in the song model with the higher rate. There was a strong correlation between the accumulated AN1 discharge difference and the amount of steering towards the side with the stronger response.

Keywords: Acoustic communication, Cricket, Female choice, Decision making

Introduction

In most species of anurans and orthopteran insects males communicate with females and other males via acoustic signals (Bradbury and Vehrencamp 1998; Gerhardt and Huber 2002; Greenfield 2002). These signals transmit information about species identity, but also about traits indicating the quality of a signaller as a potential mate, such as size, condition or genetic quality. Therefore, they are important determinants of female choice. The task of choosing the best of a number of males reliably is complicated by the fact that communication often takes place under considerable background noise levels, and that the values of signal parameters being used to assess male quality do overlap with heterospecific male signal values. Based on the studies on frogs and a cricket species, respectively, Gerhardt (1991) and Shaw and Herlihy (2000) distinguished between less variable static call elements (such as carrier frequency) and dynamic traits with comparatively high variability (such as call rate or duration). Static call elements are often associated with unimodal preference functions, where females prefer intermediate values over extremes, whereas open-ended preference functions prefer extreme values, and are associated with dynamic call elements.

One particular problem with assessing a dynamic character such as call rate is that the correct information about the actual value accumulates more or less slowly over time. For example, if two males call at two different chirp rates of 120 and 140 chirps per minute, and females assess the difference between both simultaneously, a difference of one chirp can be perceived only after a time interval of about 3 s. However, the probability of making a correct decision about the difference increases over time as information accumulates, and the slower the decision the more accurate it will be. On the other hand, the female faces a dilemma known as the speed-accuracy trade-off, where such slow decisions are probably of little value e.g. under circumstances of high predation pressure (Wickelgren 1977; Chittka et al. 2009). Thus, in many mate choice models females are assumed to optimally trade-off the expected benefits and costs of choice, and costs are assumed to be indirectly related to the time needed to search for mates, and/or the time needed to assess the differences, and decide between two or more alternatives (Real 1990; Wiegmann et al. 1996).

Here we investigate the choice of female crickets for a dynamic song parameter (chirp rate) under open-loop conditions on a walking compensator (Hedwig and Poulet 2004, 2005). Previous studies have shown that one bilateral pair of interneuron in the afferent auditory pathway, the so-called AN1-neuron, forwards the relevant information about the calling song from the prothoracic ganglion to the brain (Wohlers and Huber 1982). Results from experimental manipulation of AN1-activity demonstrated a causal relationship between the discharge difference in this pair of neurons and lateral steering (Schildberger and Hörner 1988). This confirmed the most parsimonious hypothesis for cricket orientation which suggested that females generally turn to the side more strongly excited, if the species-specific temporal pattern is represented in the AN1-activity. From our results we conclude that depending on the amount of difference between chirp rates, females perform a fast and reliable reactive steering towards the song providing the higher chirp rate, and that the minimum amount of afferent information needed to perform such steering movement is remarkably small.

Materials and methods

Female crickets (Gryllus bimaculatus de Geer) were obtained from a local supplier as last instars, raised individually to adulthood to maintain phonotactic responsiveness and used for behavioural experiments starting 1 week after the final moult. Phonotactic behaviour was studied using a highly sensitive trackball system which allowed measurement of the walking behaviour of tethered females, as described previously (Kostarakos et al. 2008; for details of a similar system see Hedwig and Poulet 2004, 2005).

Sound stimuli were generated with CoolEdit software and broadcasted by standard PC audio boards, a stereo power amplifier (NAD 214) and two mid-range speakers (Tonsil GTC 10/60). Speakers were placed at a distance of 50 cm, at an angle of 30° to the right and 30° to the left of the longitudinal body axis of the female. Sound pressure levels were calibrated at the position of the female to 80 dB sound pressure level (SPL) using a sound level meter (Rion NL-21) and integrated microphone (UC-52), and are given in SPL relative 20 μPa. The stimulus had a CF of 4.9 kHz, a pulse duration of 23 ms, an interpulse interval of 16 ms, with four pulses per chirp. We examined behavioural choices to chirp rates from 120 to 170 chirps/minute, with interchirp intervals ranging between 360 ms at chirp rates of 120/min to 210 ms at a chirp rate of 170/min.

For the behavioural experiments females were tethered above the trackball system and were allowed to acclimate for 5 min to the experimental conditions, before the playback with either a single calling song or the alternatives with different chirp rates started. From the trackball we obtained the lateral steering velocity by which the female turned to either side, and by integrating this signal we calculated the lateral deviation of the animal from a straight path. The steering to one of two alternative stimuli indicates the preference for a given song model. Phonotactic tracks were recorded for 1 min, so that the average lateral steering towards the model songs could be calculated. For each millisecond, a running average of the previous and next 5 ms was calculated to achieve a higher linearity. Positive and negative values indicated a steering to the right or left speaker, respectively. In order to determine the threshold lateral deviation where females started to steer significantly towards one of the two alternative song models we studied the phonotactic paths of females under symmetrical stimulation (song model at CF of 4.9 kHz; 80 dB SPL, 150 chirps/min; chirps of one model presented in the interchirp-interval of the alternative one). Under these conditions, females track a phonotactic path into a direction exactly straight ahead (lateral deviation zero), but with some random and meandering steering towards either side. For eight females we calculated the average ±1 SD of lateral steering in each subsequent time segment of 2 ms. The time when females exceeded this threshold of ±1 SD in the unsymmetrical choice situation was considered as the first time when they significantly steered towards one song model (see Fig. 2b).

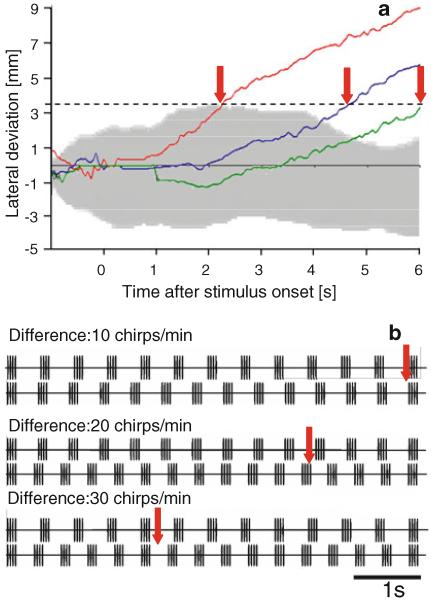

Fig. 2.

Averaged phonotactic steering of eight females in a choice between two song alternatives differing in their chirp rate by 10, 20 or 30 chirps/min. The analysis in (a) shows the first six-seconds after the onset of both stimuli (time zero) at a higher temporal resolution. The threshold lateral deviation, where females started to steer significantly towards one of the two alternative song models was studied using the phonotactic paths of females under symmetrical stimulation. Under these conditions, females track into a forward direction (lateral deviation zero), with some random and meandering steering towards either side. For eight females we calculated the average ±1 SD of lateral steering in each subsequent time segment of 2 ms (shaded area in a). The time when females exceeded this threshold (dashed line and arrows) was considered as the first time when they significantly steered towards one song model (see also arrows in b). b Stimuli in the choice situations with chirp rate differences of 10, 20 and 30 chirps/min

Previous studies indicate that positive phonotaxis in field crickets is based on the activity of the pair of AN1-interneurons (Schildberger and Hörner 1988). We therefore recorded their responses under identical stimulus situations (i.e. same SPL of 80 dB, same stimulus angles of 30°) as experienced by females on the trackball system, with the aim to determine the relevant discharge differences leading to reliable lateral steering towards one of the two song alternatives. The methods for recording the extracellular action potential activity of the pair of AN1-neurons have been described in detail by Kostarakos et al. (2008). Twenty-nine preparations were used for neurophysiological analysis.

Results

Female cricket G. bimaculatus are sensitive to variation in chirp rate, both in single stimulus trials as well as in two-choice experiments. Figure 1a shows the result for a single female and chirp rates of 120, 150 and 170 chirps/min, where the lateral deviation increases with increasing chirp rates. Furthermore, when given a choice between two song models differing in chirp rate females steered to the model with higher chirp rate, and the amount of lateral steering increased with the difference in chirp rate (Fig. 1b, c). The result also indicates that in the choice situation the absolute difference determines the amount of lateral deviation, which is about the same in a comparison between 150 versus 170 chirps/min and 130 versus 150 chirps/min. The same is true for 150 versus 160 and 140 versus 150 chirps/min (see also Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Lateral steering of a single female towards song models differing in the chirp rate in a no-choice-situation (a), and when offered a choice between two alternatives differing in the chirp rate as indicated (b). All tracks are recordings over 1 min. Note the dependency of the amount of steering on absolute chirp rate in (a), and on the chirp rate difference in the choice situation (b). The average lateral steering (±1 SD) for 14 females in a choice between song alternatives differing in chirp rate is shown in (c)

Fig. 3.

Correlation between the discharge difference in the responses of the pair of AN1-neurons, as a result of chirp rate differences, and the degree of lateral deviation (N=14). Chirp rate differences of 10 and 20/min were tested for stimulus pairs of 120 versus 130 and 140 versus 150 chirps/min, and pairs of 130 versus 150 and 150 versus 170 chirps/min, respectively. Differences of 30 and 50 chirps/min were tested for pairs of 120 versus 150, and 120 versus 170 chirps/min, respectively. The discharge differences were calculated for the time of the phonotactic path of 1 min. Error bars represent standard deviations

Females significantly choose the higher chirp rate with a difference of 20 chirps/min, but individual females consistently steered towards the higher rate even when the difference was only 10 chirps/min (see Fig. 1b). How fast do females perform the choice towards the song alternative with the higher chirp rate? For this analysis we averaged the walking paths of several females (N=8) in a choice situation with song models differing by 10, 20 and 30 chirps/min. In Fig. 2 these averages are shown, triggered by the onset of both stimuli (time zero). Before the stimuli started the females either did not walk at all, or the average direction was in the forward direction (i.e. the direction of the females’ longitudinal body axis). After the onset of both stimuli, however, females soon started to steer towards the song model with the higher chirp rate, and the steering was stronger with higher chirp rate differences (Fig. 2a). The higher resolution of the onset of steering reveals a delay of about 2.2–6 s after which females exceeded the threshold of 3.5 mm/min in lateral deviation, which is given by the random lateral deviation (mean ± 1 SD) in a forward direction (shaded area in Fig. 2a). Moreover, the time delay was shorter for the larger rate difference of 30 chirps (about 2.2 s) compared to a rate difference of 20 or 10 chirps (about 4.6 and 6 s, respectively). Thus, females tracked the higher chirp rate correctly after a remarkably short time.

If we assume that females cannot assess the different chirp rates directly by measuring the chirp periods of the two signals, the reliable steering towards the higher rate could result from simple, cumulative reactive steering towards the sound source providing more chirps. If we calculate the difference in chirp number that accumulate in the time of 2.2, 4.6 and 6.0 s before the females steered significantly towards the song model with the higher rate, this is between one and two chirps, as illustrated in Fig. 2b.

The reactive steering hypothesis (Hedwig and Poulet 2004) for the female chirp rate preference, also predicts that sensory information about the rate difference accumulates over time, and is used for successive reactive steering events towards the side presenting the higher chirp rate. We therefore analysed the discharge differences in the pair of AN1-neurons which are supposed to carry this sensory information to the brain. For the time of a recorded phonotactic path of 1 min this discharge difference is rather high with a chirp rate difference of 30 chirps, and decreases with smaller chirp rate differences (Fig. 3). These discharge differences strongly correlate with the amount of lateral steering towards these chirp rate differences (Fig. 3). Even for the minimum rate difference of 10 chirps where some females reliably steered towards the song with the higher rate the discharge difference in the pair of AN1-neurons is about 300AP’s/min, and thus about 2–3 AP’s/chirp. This is 7–10% of the average AN1-response of about 30 APs/chirp.

Discussion

Our analysis reveals that decisions about a dynamic song character such as chirp rate are made quickly and reliably by female crickets in a choice situation. They steered towards the higher chirp rate after a delay of only 2.2–6 s, depending on the rate difference between the song alternatives. This is about the time when in the song with the higher rate one or two additional chirps had been broadcast compared to the alternative (Fig. 2b). The finding strongly corroborates the reactive steering hypothesis of cricket phonotaxis (Hedwig and Poulet 2004). When they tested females with split-songs with a constant ratio of single sound pulses from the left and right side, the overall lateral deviation depended on this ratio of perceived sound pulses. Thus, in our paradigm the females steered equally often and strongly to left and right as long as equal numbers of chirps were presented on either side, but the first additional chirp in one song alternative resulted in a significant and fast shift of the overall walking path. In this way, reactive steering represents a simple mechanism which allows a reliable decision about a dynamic song character, even when the correct information about its actual value accumulates slowly over time. To put it differently: with each additional chirp in one song, alternatively compared to the other, single steering events accumulate into an overall walking direction towards the higher rate.

It is generally assumed that perceptual decision making requires at least two stages of processing: the first stage is the sensory representation of the stimuli involved, and the second is the calculation of a decision variable from such sensory representation (Graham 1989; Gold and Shadlen 2001). Neural correlates for the latter devoted to eye movements have been described for monkeys (Shadlen and Newsome 1996; Gold and Shadlen 2000), and the relationship between motion strength, viewing duration and accuracy suggested that the decision forms gradually as sensory information accumulates over time. In the case of the cricket, the sensory information for a right-left decision appears to be represented in the discharge of both side-homologous AN1-neurons, with a sufficient discharge difference driving the steering motor towards one side (Schildberger and Hörner 1988; Kostarakos et al. 2008). Our neurophysiological analysis revealed a strong correlation between the accumulated discharge difference and the amount of steering towards the side with the stronger response (Fig. 3). Extrapolating from these data the minimum discharge difference required for a significant steering towards one side would reveal a difference of 2–3 spikes/chirp, and thus in the order of less than 10% of the total response.

Clearly, the reactive steering hypothesis provides a powerful basis for the future analysis of decision making in the cricket model system, because it enables one to make precise predictions of female responses under even more real conditions, where song parameters such as carrier frequency, intensity and chirp rate of the various males have to be integrated into a single decision variable, which is most likely the discharge difference in the pair of AN1-neurons.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF), project P17986-B06 to HR. We thank Manfred Hartbauer for his support regarding the development of the trackball system, and Bertold Hedwig and Konstantinos Kostarakos for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AN

Ascending interneuron

- AP

Action potential

- CF

Carrier frequency

- SPL

Sound pressure level

Contributor Information

Daniela Trobe, Institute of Zoology, Karl-Franzens-University, Universitätsplatz 2, 8010 Graz, Austria.

Richard Schuster, Department of Forest Sciences, Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Heiner Römer, Institute of Zoology, Karl-Franzens-University, Universitätsplatz 2, 8010 Graz, Austria.

References

- Bradbury J, Vehrencamp S. Principles of animal communication. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chittka L, Skorupski P, Raine NE. Speed–accuracy tradeoffs in animal decision making. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC. Female mate choice in treefrogs: static and dynamic acoustic criteria. Anim Behav. 1991;42:615–635. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC, Huber F. Acoustic communication in insects and anurans. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gold JI, Shadlen MN. Representation of perceptual decision in developing oculomotor commands. Nature. 2000;404:390–394. doi: 10.1038/35006062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JI, Shadlen MN. Neural computations that underlie decisions about sensory stimuli. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham NVS. Visual pattern analysers. Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield MD. Mechanisms and evolution of arthropod communication. Oxford University Press; USA: 2002. Signalers and receivers. [Google Scholar]

- Hedwig B, Poulet JFA. Complex auditory behaviour emerges from simple reactive steering. Nature. 2004;430:781–785. doi: 10.1038/nature02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedwig B, Poulet JFA. Mechanisms underlying phonotactic steering in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus revealed with a fast trackball system. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:915–927. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostarakos K, Hartbauer M, Römer H. Matched filters, mate choice and the evolution of sexually selected traits. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real LA. Search theory and mate choice. I. Models of single-sex discrimination. Am Nat. 1990;136:376–404. [Google Scholar]

- Schildberger K, Hörner M. The function of auditory neurons in cricket phonotaxis. I. Influence of hyperpolarization of identified neurons on sound localization. J Comp Physiol A. 1988;163:621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Motion perception: seeing and deciding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:628–633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw KL, Herlihy DP. Acoustic preference functions and song variability in the Hawaiian cricket Laupala cerasina. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:577–584. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickelgren WA. Speed–accuracy trade-off and information precessing dynamics. Acta Psychol. 1977;41:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann DD, Real LA, Capone TA, Ellner S. Some distinguishing features of models of search behaviour and mate choice. Am Nat. 1996;147:188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlers DW, Huber F. Processing of sound signals by six types of neurons in the prothoracic ganglion of the cricket, Gryllus campestris L. J Comp Physiol (A) 1982;146:161–173. [Google Scholar]