Abstract

Background

Proximal humeral fractures are mainly associated with osteoporosis and are becoming more common with the aging of our society. The best surgical approach for internal fixation of displaced proximal humeral fractures is still being debated.

Questions/purposes

In this prospective randomized study, we aimed to investigate whether the deltoid-split approach is superior to the deltopectoral approach with regard to (1) complication rate; (2) shoulder function (Constant score); and (3) pain (visual analog scale [VAS]) for internal fixation of displaced humeral fractures with a polyaxial locking plate.

Methods

We randomized 120 patients with proximal humeral fractures to receive one of these two approaches (60 patients for each approach). We prospectively documented demographic and perioperative data (sex, age, fracture type, hospital stay, operation time, and fluoroscopy time) as well as complications. Followup examinations were conducted at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively, including radiological and clinical evaluations (Constant score, activities of daily living, and pain [VAS]). Baseline and perioperative data were comparable for both approaches. The sample size was chosen to provide 80% power, but it reached only 68% as a result of the loss of followups to detect a 10-point difference on the Constant score, which we considered the minimum clinically important difference.

Results

Complications or reoperations between the approaches were not different. Eight patients in the deltoid-split group (14%) needed surgical revisions compared with seven patients in the deltopectoral group (13%; p = 1.00). Deltoid-split and deltopectoral approaches showed similar Constant scores 12 months postoperatively (Deltoid-split 81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 74–87 versus deltopectoral 73; 95% CI, 64–81; p = 0.13), and there were no differences between the groups in terms of pain at 1 year (deltoid-split 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4 versus deltopectoral 2.5; 95% CI, 1.7–3.2; p = 0.14). No learning-curve effects were noted; fluoroscopy use during surgery and function and pain scores during followups were similar among the first 30 patients and the next 30 patients treated in each group.

Conclusions

The treatment of proximal humeral fractures with a polyaxial locking plate is reliable using both approaches. For a definitive recommendation for one of these approaches, further studies with appropriate sample size are necessary.

Level of Evidence

Level II, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Fractures of the proximal humerus are usually attributable to osteoporosis [21] and are mostly caused by low-energy trauma [5]. In Germany, there has been an increased incidence of proximal humeral fractures over the last several years with approximately 60,000 fractures in 2010 [6]. As incidence increases worldwide, further increased incidence for proximal humeral fractures can be expected as a result of an aging society [12].

For displaced fractures that meet surgical indications, the traditional deltopectoral approach is the most common approach for plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures. However, some authors have argued that this approach involves extensive soft tissue dissection and muscle retraction to gain adequate exposure to the lateral aspect of the humerus [9]. As an alternative, a less invasive, deltoid-split approach has been described with the goal of minimizing local soft tissue trauma. Early results with this approach have been shared [16, 18], although only a few nonrandomized trials have compared the two approaches [11, 17, 22]. In light of the deficiencies in the existing evidence base, we initiated a randomized controlled trial.

We hypothesized that open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with a polyaxial locking plate using a less invasive, deltoid-split approach would be superior to the deltopectoral approach with regard to complication rate, shoulder function, and pain.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Institutional review board approval by the ethics committee of the University of Marburg was obtained (AZ 50/12) in advance of this randomized controlled trial. We considered for inclusion those patients with displaced proximal humeral fractures who were treated surgically in our university hospital between December 2009 and November 2011, and 208 such patients were identified. Patients with any of the following were excluded: undisplaced fractures, age younger than 18 years, glenohumeral dislocation, concomitant ipsilateral fractures of the arm or forearm, malignancy-related fractures, and having multiple trauma.

Twenty-two patients were excluded by the previously mentioned criteria; in 27 patients implantation of a prosthesis was planned, 11 patients were planned to receive a longer plate, and 28 declined participation, leaving 120 patients included in this single-center prospective randomized trial (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart for patient selection is shown.

All patients gave their written informed consent for study participation.

With the use of a block randomization stratified by type of fracture (two-part fractures versus three- and four-part fractures), patients were randomized to either the deltoid-split or the deltopectoral approach. Presealed randomization envelopes were given by the study staff to the attending surgeon before surgery. Sixty patients were allocated to each group. Seven patients in the deltoid-split group and six patients in the deltopectoral group required arthroplasty (p = 1.000). In two cases in the deltoid-split group and in four cases in the deltopectoral group, the surgeon decided intraoperatively to perform a primary arthroplasty instead of internal fixation because the fracture could not be reliably fixed with a plate (p = 0.679). In seven patients (five deltoid-split versus two deltopectoral; p = 0.439; Fig. 1), a secondary prosthesis was necessary.

At 1-year followup, 48 (80%) patients in the deltoid-split group and 42 (70%) patients in the deltopectoral group were available for analysis (Fig. 1).

Implant

All patients received a plate osteosynthesis with the noncontact bridging plate for the proximal humerus (NCB-PH; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA). In addition to the plate, a cable wire was used to fix the greater tuberosity in three- and four-part fractures.

Surgical Approaches and Techniques

Three senior surgeons (RZ, SR, CK), who were trained in both techniques, operated on the patients in a beachchair position for both groups. The affected arm was draped to allow free motion intraoperatively. All patients received a single-shot antibiotic dose with either cephalosporin (1.5 g cefuroxime IV) or a gyrase inhibitor (a 500 mg levofloxacin IV) in the case of a contraindication intraoperatively.

The image intensifier was fixed during the whole operation attached to the patient’s head at a 45° angulation (Fig. 2). That allowed an AP view of the affected shoulder. By movement of the patient’s arm into a 90° internal rotation, a lateral view was possible.

Fig. 2.

The positioning of the patient and the image intensifier is shown.

Deltoid-split Approach

This approach consists of the anterolateral 3-cm deltoid split (Fig. 3A) and two small incisions for the three locking screws in the diaphysis of the humerus.

Fig. 3A–C.

The deltoid-split approach (A), an intraoperative view with the jig (B), and the deltopectoral approach (C) are shown.

The step-by-step explanation of the surgical technique was previously described by our working group [18].

Deltopectoral Approach

In contrast to the deltoid-split group, for the deltopectoral group, the fracture was exposed through a classical anterior approach (Fig. 3C) as described before [11]. Therefore, the 10- to 12-cm incision began at the tip of the coracoid process and ran medially in the direction of the deltoid muscle.

The rest of the surgical techniques applied did not differ between the two groups. In both groups before the plate was inserted, we fixed the rotator cuff with a cable wire. With this technique, we could manipulate the humeral head, which is helpful during reduction in some fracture types. After reduction and fixation of the fracture with the plate, we fixed the cable wire through the plate and therefore achieved fixation of the greater tuberosity.

Arthroplasty

If an adequate reduction and fixation of the fracture could not be achieved intraoperatively, primary joint arthroplasty was indicated. In addition, in cases of implant loosening in the head region, the indication was set for secondary arthroplasty, because a renewed attempt for internal fixation did not appear promising. Therefore, the existing deltopectoral approach was used or the deltoid-split was enlarged. Therefore, the skin incision was enlarged distally and medially by 7 cm. The fibers of the deltoid muscle were closed and the space between the deltoid and pectoralis major was opened to implant the prosthesis.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Postoperative rehabilitation was the same in both groups. The operated shoulder was immobilized for the first 2 days after surgery. Then, early passive and limited active motion was initiated. In cases of fractures of the greater tuberosity (eg, in three- and four-part fractures), only limited assisted abduction up to 90° was allowed for the first 6 weeks after surgery.

Data

Baseline Data

Demographic data were collected (sex, age, and fracture type) for all patients. All fractures were classified using the preoperatively performed radiographs according to the Neer system [15].

Perioperative Data

All data pertaining to the hospital course (length of stay, operative time, and fluoroscopy time) as well as complications were recorded based on prospective documentation sheets.

Followup Examinations

Standardized followup examinations were performed at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery by the same independent observer Benjamin Bockmann. He was a student and not blinded but had extensive experience in the examination of patients because he was involved in previous studies of our working group.

Evaluation of Shoulder Function

Shoulder function was measured with range of shoulder motion and the Constant-Murley score [4]. The results of the Constant score were normalized according to the Constant correction [3]. Patients were asked about their pain in the affected shoulder according to the visual analog scale (VAS) (0 = no pain at all to 10 = intolerable pain). Activities of daily living (ADL) were recorded according to the ADL score in line with Lawton and Brody [14].

Radiographic Evaluation

Radiographic evaluation in two planes was obtained on the second day, at 6 weeks, and at 6 and 12 months after surgery. Additionally, radiographs were taken in cases of shoulder pain or constraint shoulder function.

Statistics

In preparation for the study, we performed a statistical power analysis. A difference of 10 points in the Constant score concerning patients’ function was considered to be the minimal clinically important difference. With a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05, the power analysis demonstrated a sample size of 51 patients per group was needed. Assuming that there would be a dropout rate of 20%, we calculated a sample size of 60 patients for each group.

Data were collected in an Excel 2007 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). For statistical analysis, GraphPad Prism 5 (Version 5.03; GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used.

For the baseline data, we performed descriptive statistics and explorative data analysis. Patients who received an arthoplasty were not considered in the followup and further analysis. Frequencies for dichotomous variables and the means and confidence intervals for continuous variables were determined. Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine differences in the occurrence of surgical revisions and implant removal. Metric variables that showed normal distribution in the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were analyzed by the t-test. Variables that were not normal distributed differences between the two groups of patients were determined with the Mann-Whitney U test. We performed a log-rank test and made a Kaplan-Meier curve for the survivorship of the implant. Survivorship was defined as any kind of surgical revision, except implant removal. A p value < 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

Finally, we evaluated if there were any difference between the first 30 patients in both groups with respect to fluoroscopy use during surgery and function and pain scores during followup to detect a possible learning curve.

Baseline and Perioperative Data

The patients in both groups were comparable with respect to the distribution of age and sex (Table 1). According to the Neer classification [15], 15 patients in each group had a two-part fracture and 45 had a three- to four-part fracture. The mean age of patients lost to followup was not significantly different with 70 years for the deltoid-split group (p = 0.83) and 72 years for the deltopectoral group (p = 0.38); as well, the incidence of two-part (zero versus three) or three- and four-part (five versus five) fractures was comparable for patients who appeared at followup.

Table 1.

Demographic and perioperative data

| Demographic and perioperative data | Deltoid-split (n = 60) | Deltopectoral (n = 60) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.38 | ||

| Women | 48 (80%) | 44 (73%) | |

| Men | 12 (20%) | 16 (27%) | |

| Fracture | 0.84 | ||

| Two-part | 15 | 15 | |

| Three-/four-part | 45 | 45 | |

| Age (years) (95% CI) | 69 (66–72) | 67 (63–71) | 0.51 |

| Hospital stay (days) (95% CI) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 0.86 |

| Operation time (minutes) (95% CI) | 62 (57–67) | 67 (61–74) | 0.23 |

| Two-part fractures | 56 (44–69) | 55 (47–64) | 0.90 |

| Three-/four-part fractures | 64 (58–70) | 72 (64–80) | 0.14 |

| Time of fluoroscopy (minutes) (95% CI) | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 0.07 |

| Two-part fractures | 1.8 (1.2–2.3) | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 0.33 |

| Three-/four-part fractures | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | 1.7 (1.1–2.3) | 0.32 |

CI = confidence interval.

For all groups, we did not find any differences in duration of hospital stay and the time for the operation. Nevertheless, there was a tendency toward longer times for fluoroscopy in the deltoid-split group (2.0 versus deltopectoral 1.6 minutes; p = 0.07; Table 1).

Each surgeon operated on similar numbers of patients using both approaches within this study (surgeon 1: 33 versus 31; surgeon 2: 14 versus 17; surgeon 3: 13 versus 12; p = 0.822).

During the period of investigation, we had some dropouts. Six patients received a primary prosthesis, whereas seven patients received a secondary prosthesis. Four patients died during the followup period, and nine patients were not reachable for the followup investigations. Finally, four patients in the deltopectoral group were excluded from followups, because they had received an enlarged deltopectoral approach during revision surgery that was not comparable with the deltoid-split approach. There were no differences between both approaches with respect to the dropouts (Fig. 1).

Results

Complications

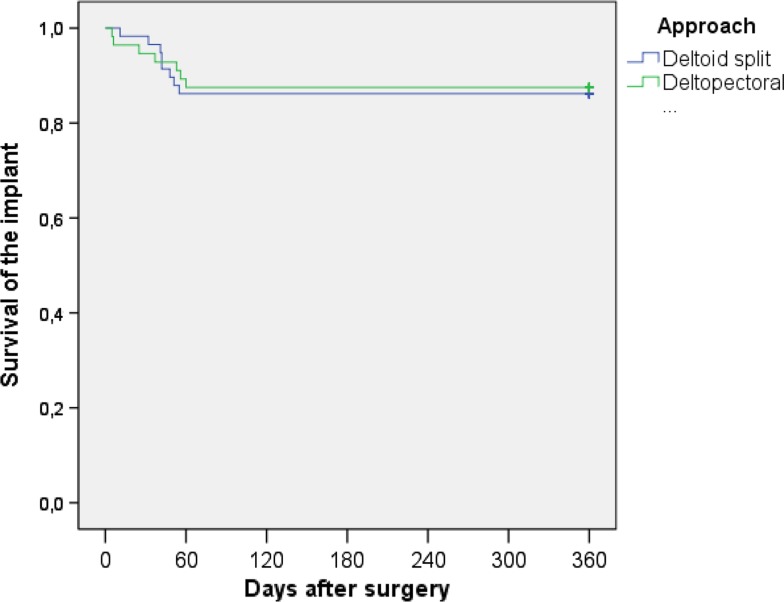

There were no differences in the frequency of complications between the two study groups. Eight patients in the deltoid-split group (14%) and seven patients in the deltopectoral group (13%, p = 1.000) had complications that required operative revision (Table 2). All complications occurred during the first 2 months postoperatively. In one patient, for example, loosening of the implant in the head region requires revision with a prosthesis (Fig. 4A–D). In this patient, a deltoid-split approach was used. Radiographs immediately after surgery showed inadequate reduction of the fracture and disrupted medial hinge (Fig. 4B). The other patients showed radiological consolidation of the fracture (Fig. 4E–F). The log-rank test showed no differences with regard to the survival of the implant between the two approaches (p = 0.847; Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Complications and plate removals

| Complication | Number/ time of occurrence (weeks) | Treatment | Deltoid-split | Deltopectoral | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw perforation | 2/6 1/8 |

Replacement | 3 | – | |

| Head implant looosening | 1/2 1/5 2/6 1/7 1/8 1/9 |

Joint replacement | 5 | 2 | |

| Shaft implant loosening | 2/1 1/4 1/8 |

Osteosynthesis | – | 4 | |

| Deep infection | 1/5 | Plate removal | – | 1 | |

| Sum | 15 | 8 | 7 | 1.000 | |

| Plate removals (wish of patients) | 9 | 8 | 1.000 | ||

Fig. 4A–F.

Radiographic results of a patient (female, 67 years, three-part fracture, deltoid-split [A]) with inadequate reduction (B), screw perforation because of secondary humeral head impaction 6 weeks after surgery (C), and secondary prosthesis (D) is shown. Another patient (female, 63 years) with a four-part fracture (E) and the radiological result 1 year after fixation is shown (F).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot for complications needing operative revision is shown.

At 1 year postoperatively, we did not see any humeral head necrosis in either group.

No damage of the axillary nerve was detected on clinical neurological examination.

In two patients (one of each group), an implant failure resulting from a fall on the shoulder and uncontrolled movements based on a postsurgical delirium made revision necessary. One patient received a prosthesis, whereas the second patient received a reosteosynthesis with a longer plate. After consolidation of the fracture in 17 patients (nine deltoid-split [16%], eight deltopectoral [14%]; p = 1.000), the implant was removed as a result of the wish of the patients. These procedures were not documented as complications.

Function

No differences were seen in functional scores between the groups at any time point. In both approaches, the Constant score 6 weeks after surgery was comparable for all fracture types and improved over time (Table 3). At the 12-month followup, no differences were identified between the two approaches. The average Constant score came to 81 (95% confidence interval [CI], 74–87) points for the deltoid split group and 73 (95% CI, 64–81) points for the deltopectoral group (p = 0.13) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Constant score during followups and evaluation of the learning curve

| Constant score during followups | Deltoid split | Deltopectoral | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 46 (42–50) | 47 (24–52) | 0.62 |

| Two-part fractures | 47 (37–58) | 51 (37–65) | 0.61 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 45 (41–49) | 46 (41–51) | 0.86 |

| 6 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 68 (62–73) | 64 (58–71) | 0.41 |

| Two-part fractures | 71 (59–82) | 63 (47–78) | 0.34 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 67 (60–73) | 65 (57–72) | 0.72 |

| 12 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 81 (74–87) | 73 (64–81) | 0.13 |

| Two-part fractures | 74 (59–88) | 74 (38–110) | 0.99 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 83 (75–90) | 72 (63–81) | 0.07 |

| 12 months (95% CI) | |||

| First 30 patients | 80 (69–90) | 74 (60–88) | |

| Last 30 patients | 82 (73–90) | 71 (60–82) | |

| p value | 0.76 | 0.74 | |

CI = confidence interval.

The ADLs at 6 weeks postoperatively were similar and increased for all groups over time (Table 4). The average ADL reached 18 (95% CI, 17–20) for the deltoid-split and 17 (95% CI, 14–19) for the deltopectoral group 12 month after operation (p = 0.31).

Table 4.

Activities of daily living during followups

| ADL during followups | Deltoid split | Deltopectoral | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 13 (12–15) | 12 (10–14) | 0.49 |

| Two-part fractures | 14 (10–18) | 15 (10–20) | 0.82 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 13 (11–14) | 11 (9–14) | 0.26 |

| 6 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 19 (17–21) | 18 (15–20) | 0.31 |

| Two-part fractures | 21 (17–24) | 18 (12–23) | 0.25 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 18 (16–20) | 18 (15–20) | 0.62 |

| 12 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 18 (17–20) | 17 (14–19) | 0.31 |

| Two-part fractures | 18 (13–23) | 18 (10–25) | 0.93 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 19 (16–21) | 17 (14–20) | 0.27 |

ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval.

Pain

No differences between groups in terms of pain were observed at any time point. During their hospital stay, the patients showed comparable pain on the VAS with respect to surgical approach (deltoid-split 4.7; 95% CI, 4.2–5.2 versus deltopectoral 4.4; 95% CI, 3.9–5.0; p = 0.44). Pain decreased during the followup period for all groups (Table 5). Again, at 1 year postoperatively, the mean pain score on VAS was not different between the groups (deltoid-split 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4 versus deltopectoral 2.5; 95% CI, 1.7–3.2; p = 0.14).

Table 5.

Pain on visual analog scale during followups

| VAS during followups | Deltoid split | Deltopectoral | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 4.7 (4.2–5.2) | 4.4 (3.9–5.0) | 0.44 |

| Two-part fractures | 4.9 (4.1–5.6) | 4.3 (3.2–5.5) | 0.43 |

| Three- 4-part fractures | 4.7 (4.1–5.2) | 4.5 (3.8–5.1) | 0.67 |

| 6 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 3.6 (3.1–4.2) | 3.9 (3.3–4.5) | 0.56 |

| Two-part fractures | 3.3 (1.9–4.7) | 3.7 (2.5–5.0) | 0.60 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 3.9 (3.2–4.6) | 0.73 |

| 6 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 3.1 (2.4–3.9) | 0.45 |

| Two-part fractures | 2.6 (1.2–3.9) | 2.6 (0.9–4.3) | 0.99 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 2.8 (2.0–3.6) | 3.3 (2.5–4.2) | 0.39 |

| 12 months (95% CI) | |||

| All patients | 1.8 (1.2–2.4) | 2.5 (1.7–3.2) | 0.15 |

| Two-part fractures | 2.6 (1.2–4.0) | 3.2 (0.4–6.0) | 0.60 |

| Three- and 4-part fractures | 1.5 (0.8–2.2) | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) | 0.14 |

VAS = visual analog scale; CI = confidence interval.

Effect of the Surgical Experience

We observed no differences that we could attribute to the learning curve over the course of this study. Operative time and time of fluoroscopy were similar for patients enrolled early in the study in comparison to patients enrolled late in the study. The Constant score for the first 30 patients in the deltoid split group was 80 (95% CI, 69–90) points, comparable to the last 30 patients with a mean Constant score of 82 (95% CI, 73–90) points (p = 0.76). Likewise, patients in the deltopectoral group showed, 12 months postoperatively, a similar Constant score for the early 30 patients compared with the last 30 patients (early 74 (95% CI, 60–88) versus late 71 (95% CI, 60–82), p = 0.74; Table 3). Pain scores at 12 months were no different between the first 30 patients and the second 30 in each group.

Discussion

Proximal humerus fractures are common, and the evidence base comparing the available surgical approaches does not include randomized trials [11, 17, 22]. This prospective randomized study was performed to evaluate the clinical outcomes after osteosynthesis of proximal humeral fractures with a polyaxial locking plate using either the less invasive, deltoid-split approach or the deltopectoral approach, specifically evaluating for differences in complication rate, function, and pain.

Our study has several further limitations. First is the limited number of patients. The power analysis was based on the Constant score, and with the numbers available, we had 68% power to detect a difference in that parameter, but the patient sample might be too small to detect modest differences in the remaining parameters. The second limitation is the followup rate of 75%; it is possible that some of those patients were treated elsewhere for complications. However, there was no differential loss to followup between the study groups, and so this tends to offset this limitation somewhat. Finally and unfortunately, we did not have any followup data from patients who received a primary arthroplasty. For this reason, we were not able to perform an intention-to-treat analysis. This is a limitation; however, we believe that the decision for a joint replacement was based on the fracture pattern and not on the surgical approach.

We found no difference between both approaches with respect to the total complication rate. Although not statistically significant, we found a different distribution of complications between the deltoid split and the deltopectoral (Table 2). All complications in the deltoid-split group affected the head region, whereas the majority of complications in the deltopectoral group was loosening of the plate in the shaft region. This may indicate that adequate reduction and fixation of the fracture is more difficult through the small incision of the deltoid-split approach. For example, in the illustrated case of fixation failure (Fig. 4C–F), inadequate reduction of the fracture was probably the main reason for this complication. Fixation on the shaft, however, might be easier with this less invasive approach. On the other hand, in a small nonrandomized study, Wu et al. found no radiological differences with respect to reduction of the fracture postoperatively and the head displacement during followup [22]. Röderer et al. found higher incidences of intraarticular screw perforation (deltoid-split 17.0% versus deltopectoral 12.8%) but lower rates of proximal screw loosening (deltoid-split 1.9% versus deltopectoral 1.3%) as compared with our results without differences between the different approaches [17]. Finally, Hepp et al. found also the same complication rates with both approaches. By contrast to our results, they did not find loosening of the plate in the shaft either using the deltoid-split or the deltopectoral approach [11]. As mentioned, maybe in a larger collective of patients, significant differences could be revealed. The overall rate for complications after internal fixation of proximal humeral head fractures is documented in the actual literature as between 10% and 34% [1, 2, 7, 8, 11, 13, 17, 19, 20, 22]. The small rate of complications in our study (14% deltoid split; 13% deltopectoral) may be explained by the fact that three experienced surgeons performed the osteosynthesis. Our previous study about the surgical technique for the less invasive approach showed 16.3% complications; the rate of complications seems to be highly associated with the experience of the surgeon [18]. This assumption is underlined by the fact that patients enrolled early in this study showed comparable clinical outcomes compared with patients enrolled late in this study (Table 3). Fortunately, in contrast to other studies that found an incidence of avascular necrosis of 4% to 5% 12 month after surgery [11, 17, 22], we did not observe any case with this complication. Although for the reason that avascular necrosis often occurs later, further evaluation is necessary to make a final statement about the incidence of avascular necrosis in our study population. The risk of damaging the axillary nerve in less invasive surgery is a frequently discussed and feared problem [10]. To protect the axillary nerve, we indicated the nerve with the index finger in the subdeltoid bursa and its course was marked on the skin. Additionally, we used a five-hole plate that was inserted with its tip contacting the bone, and we fixed screws in the three distal holes, far away from the axillary nerve [18]. A similar technique is described by Acklin et al. [1]; like us, they saw no injury to the axillary nerve in clinical observation.

Shoulder function 1 year postoperatively was comparable between groups and comparable to other studies. Acklin et al. [1] reported 18 months after minimally invasive surgery a mean Constant score of 75 points. Voigt et al. [20] showed comparable outcomes for polyaxial locking plates (Constant score 73 points) and monoaxial locking plates (Constant score 81 points) by using the deltopectoral approach. An additional nonrandomized multicenter study also investigated clinical outcomes for the deltoid-split and deltopectoral approaches. That study found 12 months postoperatively a significantly better Constant score for the deltopectoral approach (deltopectoral 81 points versus deltoid-split 73 points) [11]. In contrast, Wu et al. [22] found similar results 12 months after surgery for both approaches (deltopectoral 77 points versus deltoid-split 78 points). In our study, the mean Constant scores for both groups were similar (Table 3).

We did not find a difference in the average pain score between patient groups during the followup period (Table 4). By contrast, Hepp et al. found less pain after the deltoid-split approach compared with the deltopectoral approach 3 months after surgery, although in this study the difference was no longer evident during subsequent followup points [11]. Similar results with less pain in the deltoid split group at discharge were found by Röderer et al. [17]. In our opinion, a long-term effect on pain scores resulting from the less invasive approach could not be expected, but similar to these previous findings, we did suppose a benefit in terms of pain in the first postsurgical month. Explanations for the different findings between studies could be differences in pain assessment as compared with Hepp et al. and that we performed a randomized controlled trial, whereas others compared the results of the different approaches between different hospitals. For example, Röderer et al. found a longer operation time in the delotpectoral group that might indicate more complex fracture types and therefore poses a bias [17].

We found that proximal humeral fractures can be effectively treated with a polyaxial locking plate through either the deltoid-split or the deltopectoral approach. Based on our result, a definitive recommendation for one of these approaches cannot be given. For clarity, further studies with appropriate sample sizes are necessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Kühne who did the surgery for some of the patients. In addition, we thank Daphne Asimenia Eschbach for valuable guidance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

Contributor Information

Benjamin Buecking, Email: buecking@med.uni-marburg.de.

Juliane Mohr, Email: mohrj@med.uni-marburg.de.

References

- 1.Acklin YP, Stoffel K, Sommer C. A prospective analysis of the functional and radiological outcomes of minimally invasive plating in proximal humerus fractures. Injury. 2013;44:456–460. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Björkenheim JM, Pajarinen J, Savolainen V. Internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with a locking compression plate: a retrospective evaluation of 72 patients followed for a minimum of 1 year. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:741–745. doi: 10.1080/00016470410004120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constant CR. [Assessment of shoulder function] [in German] Orthopade. 1991;20:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Court-Brown CM, Garg A, McQueen MM. The epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:365–371. doi: 10.1080/000164701753542023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeStatis Statistisches Bundesamt. Hospital statistics. Wiesbaden 2011; Available at: http://www.gbe-bund.de/oowa921-install/servlet/oowa/aw92/dboowasys921.xwdevkit/xwd_init?gbe.isgbetol/xs_start_neu/&p_aid=i&p_aid=36857213&nummer=702&p_sprache=D&p_indsp=522&p_aid=9442669;Download. Accessed June 14, 2012.

- 7.Duralde XA, Leddy LR. The results of ORIF of displaced unstable proximal humeral fractures using a locking plate. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fankhauser F, Boldin C, Schippinger G, Haunschmid C, Szyszkowitz R. A new locking plate for unstable fractures of the proximal humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:176–181. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000137554.91189.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner MJ, Griffith MH, Dines JS, Briggs SM, Weiland AJ, Lorich DG. The extended anterolateral acromial approach allows minimally invasive access to the proximal humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;434:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000152872.95806.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ, Rollins KE. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD000434. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hepp P, Theopold J, Voigt C, Engel T, Josten C, Lill H. The surgical approach for locking plate osteosynthesis of displaced proximal humeral fractures influences the functional outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Szabo RM, Marder RA. Epidemiology of humerus fractures in the United States: nationwide emergency department sample, 2008. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:407–414. doi: 10.1002/acr.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Königshausen M, Kübler L, Godry H, Citak M, Schildhauer TA, Seybold D. Clinical outcome and complications using a polyaxial locking plate in the treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures. A reliable system? Injury. 2012;43:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neer CS. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1077–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Röderer G, Abouelsoud M, Gebhard F, Böckers TM, Kinzl L. Minimally invasive application of the non-contact-bridging (NCB) plate to the proximal humerus: an anatomical study. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:621–627. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318157f0cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Röderer G, Erhardt J, Kuster M, Vegt P, Bahrs C, Kinzl L, Gebhard F. Second generation locked plating of proximal humerus fractures—a prospective multicentre observational study. Int Orthop. 2011;35:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruchholtz S, Hauk C, Lewan U, Franz D, Kühne C, Zettl R. Minimally invasive polyaxial locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2011;71:1737–1744. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823f62e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Südkamp N, Bayer J, Hepp P, Voigt C, Oestern H, Kääb M, Luo C, Plecko M, Wendt K, Köstler W, Konrad G. Open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with use of the locking proximal humerus plate. Results of a prospective, multicenter, observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1320–1328. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voigt C, Geisler A, Hepp P, Schulz AP, Lill H. Are polyaxially locked screws advantageous in the plate osteosynthesis of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly? A prospective randomized clinical observational study. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25:596–602. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318206eb46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Curtis JR, Delzell E, Gary L, Kilgore M, Saag K. Which fractures are most attributable to osteoporosis? J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu CH, Ma CH, Yeh JJ, Yen CY, Yu SW, Tu YK. Locked plating for proximal humeral fractures: differences between the deltopectoral and deltoid-splitting approaches. J Trauma. 2011;71:1364–1370. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820d165d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]