Abstract

Background

Despite the overall success of total joint arthroplasty, patients undergoing this procedure remain susceptible to cognitive decline and/or delirium, collectively termed postoperative cognitive dysfunction. However, no consensus exists as to whether general or regional anesthesia results in a lower likelihood that a patient may experience this complication, and controversy surrounds the role of pain management strategies to minimize the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Questions/purposes

We systematically reviewed the English-language literature to assess the influence of the following anesthetic and/or pain management strategies on the risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty: (1) general versus regional anesthesia, (2) different parenteral, neuraxial, or inhaled agents within a given type of anesthetic (general or regional), (3) multimodal anesthetic techniques, and (4) different postoperative pain management regimens.

Methods

A systematic search was performed of the MEDLINE® and EMBASE™ databases to identify all studies that assessed the influence of anesthetic and/or pain management strategies on the risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction after elective joint arthroplasty. Twenty-eight studies were included in the final review, of which 21 (75%) were randomized controlled (Level I) trials, two (7%) were prospective comparative (Level II) studies, two (7%) used a case-control (Level III) design, and three (11%) used retrospective comparative (Level III) methodology.

Results

The evidence published to date suggests that general anesthesia may be associated with increased risk of early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the early postoperative period as compared to regional anesthesia, although this effect was not seen beyond 7 days. Optimization of depth of general anesthesia with comprehensive intraoperative cerebral monitoring may be beneficial, although evidence is equivocal. Multimodal anesthesia protocols have not been definitively demonstrated to reduce the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Nonopioid postoperative pain management techniques, limiting narcotics to oral formulations and avoiding morphine, appear to reduce the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Conclusions

Both anesthetic and pain management strategies appear to influence the risk of early cognitive dysfunction after elective joint arthroplasty, although only one study identified differences that persisted beyond 1 week after surgery. Investigators should strive to use accepted, validated tools for the assessment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and to carefully report details of the anesthetic and analgesic techniques used in future studies.

Introduction

Total joint arthroplasty remains among the most successful contemporary surgical interventions. Due in part to advances in preoperative medical optimization and evidence-based clinical care pathways, notwithstanding the substantial invasiveness of arthroplasty procedures, the incidence of major medical and surgical complications after elective joint arthroplasty remains low, with reported 30-day mortality rates of around 0.2% [30]. Despite these efforts, however, patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty remain susceptible to postoperative cognitive decline and/or delirium, with reported rates ranging from 7% to 75%, depending on the definition, patient population, and assessment tools used [11, 37]. These adverse events can result in delayed mobilization and discharge from hospital, long-term cognitive dysfunction, and potentially increased rates of return to hospital and mortality [42]. As a result, postoperative cognitive dysfunction can have a significant impact on both health resource utilization and patients’ health-related quality of life.

The etiology of postoperative cognitive dysfunction is multifactorial, with a number of nonmodifiable factors reported to influence the incidence, including major surgery, older age, and preexisting cognitive impairment (Table 1) [10, 21]. A number of modifiable factors also have been reported by investigators, including the quality of perioperative pain control and quantity and classes of medications used [10]. However, no consensus exists concerning the optimal choice of anesthetic and pain management strategies to minimize the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in surgical patients.

Table 1.

Predisposing and precipitating factors reported to be associated with delirium and/or postoperative cognitive dysfunction in hospitalized patients [10, 21]

| Factor |

|---|

| Predisposing |

| Increased age |

| Male sex |

| Preexisting cognitive impairment |

| Previous delirium |

| Immobility |

| Sensory impairment (auditory, visual) |

| Decreased oral intake |

| Polypharmacy |

| Narcotic or benzodiazepine use |

| Excessive alcohol intake |

| Tobacco use |

| Trauma |

| Severe illness |

| Precipitating |

| Anticholinergic drugs |

| Benzodiazepines |

| Primary intracranial neurologic disease |

| Infection |

| Iatrogenic complications |

| Shock |

| Hypoxia |

| Fever |

| Hypothermia |

| Dehydration |

| Poor nutritional status |

| Metabolic abnormalities |

| Anemia |

| Surgery |

| Intensive care unit admission |

| Urinary catheter use |

| Use of restraints |

| Acute pain |

| Sleep deprivation |

Given this, we systematically reviewed the English-language literature to assess the influence of anesthetic and/or pain management strategies on the risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty. Specifically, we determined whether the risks of these conditions are affected by the use of (1) general as compared to regional anesthesia, (2) different parenteral, neuraxial, or inhaled agents within a given type of anesthetic (general or regional), (3) multimodal anesthetic techniques, and (4) different postoperative pain management regimens.

Search Criteria and Strategy

Eligibility Criteria

Original studies comparing the effect of different anesthetic and/or pain management strategies on the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction after elective joint arthroplasty were deemed eligible for review. Anesthetic and/or pain management strategies were defined as any combination of oral, parenteral, inhaled, and/or regional medications administered immediately before induction of anesthesia, during the surgical procedure, or after surgery but before discharge from hospital. Different types of anesthesia (eg, general, neuraxial, regional) were considered to be different anesthetic strategies for the purposes of this review. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction was defined as encompassing any acute change in neurocognitive status after surgery, including postoperative cognitive decline, delirium, or confusion. With the exception of dementia, no specific limitations were applied to the type or magnitude of postoperative cognitive dysfunction considered eligible for inclusion in the present review. Any studies that included either (1) only patients who underwent elective major joint arthroplasty (specifically, hip, knee, shoulder, elbow, or ankle) or (2) patients who underwent any of a number of different surgical procedures including elective orthopaedic surgery requiring hospitalization were deemed eligible for inclusion. Only comparative studies including at least two different pain management strategies, irrespective of study design, were deemed eligible. Case series assessing the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction with a single pain management strategy were excluded. Review articles, published abstracts, letters to the editor, study protocols, case reports (defined as studies encompassing < 10 patients), and reports without English full-text versions were similarly excluded.

Information Sources and Search

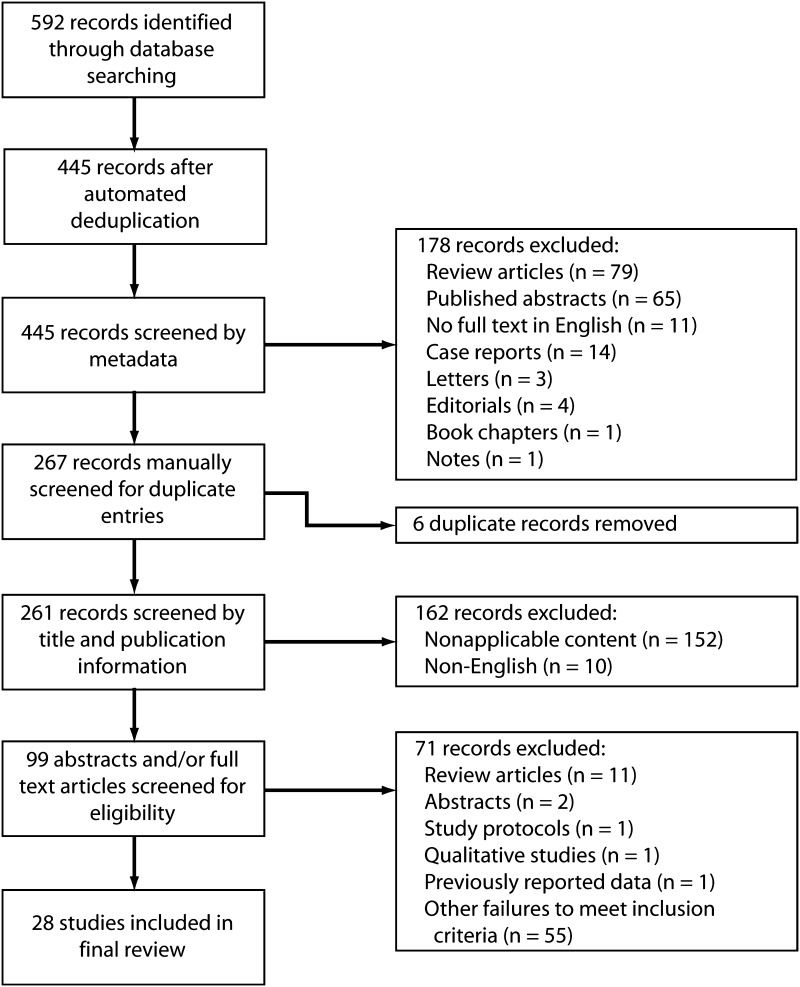

An electronic search was performed, in duplicate, of the Ovid MEDLINE® and EMBASE™ databases to identify all studies published up to March 2013 assessing the effect of anesthetic and/or pain management strategies on postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion among the authors. The following search string was used to query citation titles and abstracts: “(delirium or cognitive or cognition or confusion or confused) and (pain management or anesthesia or anaesthesia or anesthetic or anaesthetic or spinal or epidural or multimodal or pain control) and (arthroplasty or joint replacement or elective joint or orthopaedic or orthopedic or non-cardiac or non cardiac).” A second search of the same databases was performed using the following search string, limited to MeSH headings: “(pain management or anesthesia) and orthopedic procedures and (delirium or postoperative complications).” The two searches yielded 592 records when combined using the OR operator, with 445 remaining after automated deduplication. A flow diagram of the search process is shown (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram illustrates the systematic search process used to identify the studies included in the final review.

Study Selection

Citation records were extracted to spreadsheet software and sorted by metadata tags. We excluded 178 records deemed to not meet our eligibility criteria based on publication type metadata, including 79 review articles, 65 published abstracts, 14 case reports, 11 reports without full-text versions in English, four editorials, three letters to the editor, one note, and one book chapter. The remaining 267 records were sorted by title and manually screened for duplicate studies, with six duplicate citations identified and removed. The remaining records were screened by title and publication type. Any studies that definitely did not meet eligibility criteria were discarded, with 162 records excluded for the following reasons: nonapplicable content (n = 152) and no full-text English version available (n = 10). Full-text versions of the remaining 99 records, which had been judged to be either probably relevant or of unknown relevance, were obtained. These were screened and/or read by two reviewers (MGZ, RG) to identify those studies that definitely met the inclusion criteria for this review. Seventy-one records were found to be ineligible after screening and were excluded, leaving 28 studies in the final review [2–4, 7, 12, 14–20, 24, 26, 27, 29, 33–36, 38, 39, 41, 44–48].

Data Collection

Data from the included studies were extracted to spreadsheet software for analysis. The specific information extracted included the following: (1) study details, including study design and level of evidence; (2) study population details, including number of patients and their mean age (range), any reported inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the surgical procedures performed; (3) details of pain management strategies, including type of anesthesia and analgesic and/or anesthetic medications given including route and dosing, when applicable; and (4) details of assessment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, including assessment tools, time point and frequency of assessment(s), and reported incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction at various time points. In cases where rates and proportions of postoperative cognitive dysfunction were given but no statistical comparison was provided, p values were calculated using the chi-square statistic.

Study Designs and Populations

The large majority of studies identified (21 of 28, 75%) used a prospective randomized design to compare the effects of pain management strategies on postoperative cognitive dysfunction. However, of those studies, only nine of 21 (43%) explicitly reported blinding of patients, clinicians, and/or assessors to the participants’ treatment arm allocation [4, 12, 15, 20, 24, 27, 29, 47, 48]. Only nine of 21 (43%) reported performing an a priori power calculation for the outcome of postoperative cognitive dysfunction [4, 16, 24, 27, 29, 34, 38, 39, 48], with one of these studies failing to recruit a sufficient number of patients [38]. Of the remaining seven studies, two used a prospective comparative design [2, 41], two used a case-control design [33, 44], and three used a retrospective comparative design [17, 19, 36].

Nineteen studies encompassing 2824 patients were limited to those who had undergone elective total joint arthroplasty only. This included eight studies of patients who underwent either TKA or THA [7, 12, 17, 18, 20, 24, 36, 47], eight studies of patients who underwent unilateral TKA [15, 19, 26, 35, 39, 41, 45, 48], two studies of patients who underwent unilateral THA [16, 34], and one study of patients who underwent bilateral TKA [46]. The remaining nine studies encompassing 2426 patients investigated postoperative cognitive dysfunction in a mixed major noncardiac surgical population, which included patients who underwent elective joint arthroplasty.

A range of definitions and assessment tools for postoperative cognitive dysfunction were reported. Eleven studies assessed postoperative cognitive dysfunction using multiple validated neuropsychologic and/or cognitive tests [2, 4, 14, 24, 29, 35, 38, 41, 44, 45, 47]. Eleven studies assessed either cognitive dysfunction or confusion without specifying diagnostic criteria [7, 15–20, 27, 34, 36, 48]. Five studies assessed postoperative cognitive dysfunction using either the Confusion Assessment Method, which has been validated for delirium screening [22], or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [1] criteria for delirium [4, 26, 29, 33, 46]. Four studies assessed postoperative cognitive dysfunction by an observed change in scores on the Mini Mental Status Examination [4, 12, 18, 47], while two assessed for change on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [3, 35].

Results

The Use of General Versus Regional Anesthesia

The studies reported to date suggest that general anesthesia may be associated with increased cognitive dysfunction in the early postoperative period, although any differences appear to resolve within the first week after surgery (Table 2). Nine studies were identified that compared the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction after general versus regional anesthesia. Three studies reported worse cognitive function and/or confusion in patients who had undergone surgery under general anesthesia between 1 and 7 days after surgery [3, 26, 38]. One of these studies limited assessment times to a maximum of 3 days postoperatively [3], while the other two found no differences in cognitive function at the second postoperative assessment (Postoperative Day 2 and 3 months after surgery, respectively). In the remaining six studies that failed to find any difference in cognitive function based on type of anesthesia [2, 14, 24, 35, 41, 45], the first postoperative assessment ranged from 1 week to 3 months after surgery, suggesting that any differences that may have been present immediately after surgery had resolved before the first evaluation. Overall, the available evidence suggests that general anesthesia may be associated with an increased risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the immediate postoperative period. However, this effect appears to be transient, with no data suggesting that these differences are maintained more than 1 week after surgery.

Table 2.

Studies comparing the incidence of POCD with general versus regional anesthesia

| Study | Year | Study group | Age (years)* | General anesthesia | Regional anesthesia | Cognitive variables evaluated | Assessment time | Difference found? | Time point of latest significant difference | Time point of earliest similar incidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications used | Number of patients | Technique | Medications used | Number of patients | |||||||||

| Prospective randomized controlled studies | |||||||||||||

| Jones et al. [24] | 1990 | TKA, THA | NR (60+) | Diazepam, thiopental, pancuronium, N2O, halothane, fentanyl | 72 | Spinal | Bupivicaine, midazolam | 74 | Neuropsychologic tests | 3 months | No | 3 months | |

| Prospective randomized studies | |||||||||||||

| Anwer et al. [3] | 2006 | Noncardiac major surgery | 62 (60–64) | Midazolam, thiopental, halothane, N2O | 30 | Spinal or epidural | Bupivicaine or lidocaine; midazolam | 30 | WAIS-R | Preop 1 day 3 days | Yes | 3 days (greater POCD in GA) | |

| Kudoh et al. [26] | 2004 | TKA | 75 (NR) | Fentanyl, propofol, vecuroniom | 75 | Spinal + LMA | Bupivicaine; propofol | 75 | Confusion (CAM) | POD 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes | 1 day (greater POCD in GA) | 2 days |

| Rasmussen et al. [38] | 2003 | Noncardiac major surgery | 71 (61–84) | Variable | 217 | Spinal or epidural | Variable | 211 | Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 7 days 3 months | Yes | 7 days (greater POCD in GA) | 3 months |

| Williams-Russo et al. [45] | 1995 | TKA | 69 (NR) | Thiopental, fentanyl, vecuronium, isflurane, N2O | 128 | Epidural | Lidocaine or bupivicaine, midazolam, fentanyl | 134 | Neuropsychologic tests Clinical delirium | Preop 1 week 6 months | No | 1 week | |

| Nielson et al. [35] | 1990 | TKA | 60–86 | Thiopental, succinylcholine, N2O, isoflurane, fentanyl | 39 | Spinal | Tetracaine or bupivicaine | 25 | WAIS Wechsler Memory Scale Neuropsychologic tests Sickness Impact Profile |

Preop 3 months | No | 3 months | |

| Ghoneim et al. [14] | 1988 | Noncardiac major surgery | 61 (25–86) | Diazepam, thiopental, isoflurane or enflurane, N2O; variable use of fentanyl | 53 | Spinal (38), epidural (14) | Tetracaine (spinal) or bupivicaine (epidural); variable use of diazepam, midazolam, fentanyl | 52 | Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 1st outpatient visit 3 months | No | 1st outpatient followup | |

| Prospective comparative studies | |||||||||||||

| Rodriguez et al. [41] | 2005 | TKA | 69 (45–82) | Fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, atracurium, sufentanil, sevoflurane, N2O | 12 | Spinal | Midazolam; neuraxial agent NR | 25 | Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 1 week 3 months | No | 1 week | |

| Ancelin et al. [2] | 2001 | Orthopaedic elective | 73 (64–87) | Variable | 52 | Regional (variable) | Variable | 88 | Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 9 days 3 months | No | ||

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; POCD = postoperative cognitive dysfunction; NR = not reported; N2O = nitrous oxide; LMA = laryngeal mask airway; WAIS-R = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale, revised form; CAM = Confusion Assessment Method; WAIS = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale; preop = preoperatively; POD = postoperative day; GA = general anesthesia.

The Use of Different Anesthetic and/or Analgesic Techniques Within a Given Type of Anesthesia

Optimization of depth of general anesthesia with comprehensive intraoperative cerebral monitoring may be beneficial, although the quantity of evidence on this question and other related questions is limited, and the effect sizes—where effects were observed—generally were small. Four studies investigated the impact of differences in general anesthetic technique on the incidence and/or severity of postoperative cognitive dysfunction (Table 3). The factors studied included the use of intraoperative cerebral monitoring (n = 3) and use of nitrous oxide (n = 1). Wong et al. [47] reported that maintenance of anesthesia using EEG monitoring was associated with faster time to orientation in the recovery room but no difference in daily psychometric test results up to Postoperative Day 3. Similarly, Steinmetz et al. [44] found no difference in depth of anesthesia as tracked using EEG monitoring between patients who did and did not have postoperative cognitive dysfunction at 1 week after surgery. In contrast, Ballard et al. [4] found that patients who had depth of anesthesia optimized using both EEG and regional brain oxygenation monitoring had differences in postoperative cognitive dysfunction up to final followup time of 52 weeks. However, none of these studies assessed the effectiveness of cerebral monitoring stratified by potential risk factors for cognitive dysfunction. The final study suggested that the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction was not affected by the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for the maintenance of anesthesia [29].

Table 3.

Studies comparing the effects of different techniques within a given type of anesthesia on POCD

| Study | Year | Study group | Age (years)* | Anesthetic type | Group 1 | Group 2 | Variables evaluated | Assessment time | Difference found? | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention/ characteristic | Number of patients | Intervention/ characteristic | Number of patients | |||||||||

| Prospective randomized blinded studies | ||||||||||||

| Ballard et al. [4] | 2012 | Noncardiac major surgery | 75 (72–81) | GA | EEG and regional brain oxygenation monitoring | 34 | Typical protocol, no advanced monitoring | 38 | MMSE CAM Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 1 week 12 weeks 52 weeks | Yes | Decreased mild cognitive decline at all time points (p = 0.018 at 1 week, p = 0.02 at 12 weeks, p = 0.015 at 52 weeks) |

| Leung et al. [29] | 2006 | Noncardiac major surgery | 74 (65–95) | GA | N2O and O2 maintenance | 105 | O2 maintenance | 105 | CAM neuropsychologic tests | POD 1, 2 | No | No difference in delirium (41.9% vs 43.8%) or cognitive decline (14.8% vs 18.6%) |

| Wong et al. [47] | 2002 | TKA, THA | 71 (NR) | GA | EEG monitoring | 29 | Typical protocol, no advanced monitoring | 31 | MMSE Neuropsychologic tests Clinical confusion | 30, 60, 120 minutes 24,48,72 hours | No | No difference in neuropsychological tests (p values not reported) |

| Fernandez-Galinski et al. [12] | 2005 | TKA, THA | 75 (70–88) | Spinal | 4 mg bupivicaine 15 μg fentanyl 15 μg clonidine | 31 | 6.25 mg bupivicaine 25 μg fentanyl | 30 | MMSE | On arrival to recovery room | No | No difference in MMSE change between groups (p = 0.957) |

| Prospective randomized studies | ||||||||||||

| Rasmussen et al. [39] | 2006 | TKA | 71 (NR) | Spinal | 65% xenon | 20 | Propofol infusion | 16 | ISPOCD cognitive tests | Preop At discharge 10–14 weeks | No | Similar incidence of cognitive decline at discharge (p = 0.88) and 3-month followup (p = 0.77) |

| Case-control studies | ||||||||||||

| Steinmetz et al. [44] | 2010 | Noncardiac major surgery | 68 (61–83) | GA with EEG monitoring | POCD positive | 9 | POCD negative | 56 | Neuropsychologic tests | Preop 1 week | No | No difference in depth of anesthesia (time spent at different depths) between patients who did and did not develop POCD (specific values not reported) |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; POCD = postoperative cognitive dysfunction; NR = not reported; GA = general anesthesia; N2O = nitrous oxide; O2 = oxygen; CAM = Confusion Assessment Method; MMSE = Mini Mental Status Examination; ISPOCD = International Study on Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction; preop = preoperatively.

Two studies assessed differences in techniques for spinal anesthesia but failed to show any difference in postoperative cognitive dysfunction in either case [12, 39]. Specifically, both the addition of intrathecal clonidine and the maintenance of sedation with inhaled xenon as compared to intravenous (IV) propofol did not have an effect on the development of postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Multimodal Anesthetic Techniques

Overall, the retrospective comparative designs, variability in anesthetic and analgesic regimens, and limited number of patients in the few studies that investigated this question precluded the assessment of the impact of multimodal protocols on the risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction after elective joint arthroplasty. Only two studies were identified that assessed the impact of multimodal anesthesia on postoperative cognitive dysfunction, with equivocal findings (Table 4). Hebl et al. [17] compared the use of a multimodal pathway that emphasized the use of lumbar plexus and/or femoral nerve catheters for postoperative perineural anesthesia to historical controls. While the authors identified a greater incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the control group (15% versus 0%; p < 0.01), both the diagnostic criteria for postoperative cognitive dysfunction and the anesthetic and analgesic regimes used in the control group were not clearly reported, complicating interpretation of the findings. In contrast, Peters et al. [36] compared a multimodal protocol emphasizing the use of periarticular intraoperative injection + long-acting oral narcotics to a historical control group that received IV patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and found a numerically higher incidence of confusion in the multimodal group (8% versus 4%). However, the diagnostic criteria for confusion were not specified, and the study was not specifically powered to detect a difference in postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Table 4.

Summary of studies comparing the effect of multimodal anesthesia protocols on POCD

| Study | Year | Study group | Age (years)* | Multimodal group | Standard group | Variables evaluated | Assessment time | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Details | Number of patients | Details | Number of patients | |||||||

| Retrospective comparative studies | ||||||||||

| Hebl et al. [17] | 2005 | TKA, THA | 67 (55–72) | Multimodal with continuous lumbar plexus catheter | 40 | Nonmultimodal pathway anesthesia | 40 | Cognitive dysfunction (method not specified) | Not specified | Cognitive dysfunction higher in nonmultimodal group (15% vs 0%; p < 0.01) |

| Peters et al. [36] | 2006 | TKA, THA | 59 (NR) | Spinal with bupivicaine + fentanyl; preop and postop long-acting narcotic + NSAIDS; intraarticular injection; femoral nerve block + catheter in TKA | 100 | GA or spinal (with bupivicaine + morphine); IV PCA postop; femoral nerve block + catheter in TKA | 100 | Confusion (method not specified) | Not specified | Higher POCD in multimodal group (8% vs 4%; p = 0.372) |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; POCD = postoperative cognitive dysfunction; NR = not reported; preop = preoperative; postop = postoperative; GA = general anesthesia; IV PCA = intravenous patient-controlled analgesia.

Postoperative Pain Management Strategies

In general, the findings suggest that pain management strategies that minimize the use of narcotics postoperatively have a beneficial effect on early postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Twelve studies were identified that compared the effect of different postoperative pain management strategies on the risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction (Table 5). Langford et al. [27] reported decreased postoperative cognitive dysfunction on Postoperative Day 2 (1.8% versus 5%; p = 0.006) with the use of standing IV parecoxib as compared to placebo. YaDeau et al. [48] reported decreased postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients who received a single-shot femoral nerve block immediately before TKA (2.5% versus 0%), while Marino et al. [34] found decreased postoperative cognitive dysfunction with the use of continuous lumbar or femoral block as compared to IV PCA alone (0%, 1.3%, and 10.7%, respectively). In contrast, intraarticular infusion of bupivacaine after TKA was not found to change the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction as compared to placebo [15].

Table 5.

Summary of studies comparing the effect of different postoperative pain management regiments on postoperative cognitive dysfunction

| Study | Year | Study group | Age (years)* | Anesthetic | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Number of patients | Intervention | Number of patients | Intervention | Number of patients | |||||

| Prospective randomized blinded studies | ||||||||||

| Goyal et al. [15] | 2013 | TKA | 64 (35–81) | Spinal | Intraarticular bupivicaine infusion × 2 days | 80 | Intraarticular normal saline infusion × 2 days | 80 | ||

| Langford et al. [27] | 2009 | Noncardiac major surgery | 53 (18–80) | Variable | IV parexocib × 3 days, then oral valdecoxib × 7 days; opioids as needed | 525 | IV placebo × 3 days, then oral placebo × 7 days; opioids as needed | 525 | ||

| Marino et al. [34] | 2009 | THA | 67 (NR) | Spinal | Continuous lumbar plexus block (ropivicaine) + PCA | 75 | Continuous FNB (ropivicaine) + PCA | 75 | PCA (hydromorphone) | 75 |

| Inan et al. [20] | 2007 | TKA, THA | 69 (60–75) | GA | Epidural PCA (morphine) | 24 | IV PCA (morphine) | 24 | ||

| Leung et al. [29] | 2006 | Noncardiac major surgery | 74 (65–95) | GA | Delirium + | 100 | No delirium | 128 | ||

| YaDeau et al. [48] | 2005 | TKA | 73 (NR) | Spinal + PCEA (bupivicaine + hydromorphone) | Single-injection FNB | 41 | No FNB | 39 | ||

| Prospective randomized studies | ||||||||||

| Hartrick et al. [16] | 2006 | THA | 63 (median; mean and range NR) | Variable | Fentanyl transdermal PCA | 395 | Morphine IV PCA | 404 | ||

| Herrick et al. [18] | 1996 | TKA, THA | 72 (65–85) | Variable | PCA morphine | 49 | PCA fentanyl | 47 | ||

| Colwell and Morris [7] | 1995 | TKA, THA | NR | Spinal | IV PCA morphine | 91 | IM morphine prn | 93 | ||

| Williams-Russo et al. [46] | 1992 | Bilateral TKA | 68 (NR) | GA | Epidural bupivicaine + fentanyl infusion | 25 | IV fentanyl infusion | 26 | ||

| Case-control studies | ||||||||||

| Marcantonio et al. [33] | 1994 | Noncardiac major surgery | 73 (NR) | Variable | Delirium + | 91 | No delirium | 154 | ||

| Retrospective comparative studies | ||||||||||

| Ilahi et al. [19] | 1994 | TKA | 67 (33–86) | GA | Continuous fentanyl + bupivicaine epidural | 80 | Continuous morphine + bupivicaine epidural | 56 | ||

| Study | Variables evaluated | Assessment time | Group 1 incidence | Group 2 incidence | Group 3 incidence | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective randomized blinded studies | ||||||

| Goyal et al. [15] | Confusion (not specified) | Not specified | 2.6% | 1.6% | Similar rates of confusion (p = 0.302) Less narcotic use in experimental group POD 2 and 3 |

|

| Langford et al. [27] | Confusion (patient-reported) | POD 2, 3, 4 | POD 2: 1.8% POD 3: 1.6% POD 4: 1.6% |

POD 2: 5% POD 3: 3.6% POD 4: 2.2% |

Lower confusion on POD 2 (p = 0.006) Similar on POD 3 (p = 0.051) and 4 (p = 0.498) |

|

| Marino et al. [34] | Delirium (details not specified) | Not specified | 0% | 1.3% | 10.70% | Higher incidence with PCA alone (p < 0.05) |

| Inan et al. [20] | Confusion Brief Symptom Inventory |

NR POD 2 |

Confusion: 12.5% | Confusion: 12.5% | No difference in rates of confusion (agitation + disorientation) No difference in psychological scoring preop or postop |

|

| Leung et al. [29] | Regression analysis | Delirium associated with: IV PCA vs oral opioids (OR: 3.75; 95% CI 1.27–11.01) benzodiazepine use postop (OR: 2.29; 95% CI: 1.21–4.36) |

||||

| YaDeau et al. [48] | Confusion (not specified) | Not specified | Confusion: 0% | Confusion: 2.5% | Similar incidence of confusion (p = 0.488) Greater volume of epidural used POD 2 in control group |

|

| Prospective randomized studies | ||||||

| Hartrick et al. [16] | Confusion (not specified) | Not specified | 0.3% | 2.0% | Higher incidence of confusion with IV morphine (p = 0.048) | |

| Herrick et al. [18] | Clinical confusion MMSE SPMSQ |

Daily for 5 days | Confusion: 14% | Confusion: 4% | No difference in confusion (p = 0.160 Greater drop in MMSE on POD 1(p = 0.04) for morphine Greater drop in SPMSQ on POD 5 (p < 0.05) for fentanyl |

|

| Colwell and Morris [7] | Confusion (not specified) | Not specified | NR | 3% (3/93) | No difference in complications reported | |

| Williams-Russo et al. [46] | DSM criteria for delirium | Daily | No difference in incidence of delirium | |||

| Case-control studies | ||||||

| Marcantonio et al. [33] | Delirium (CAM or clinical documentation) | Daily | Meperidine: 65% Epidural: 64% Benzodiazepine: 21% |

Meperidine: 42% Any epidural: 42% Benzodiazepine: 8% |

Higher rate with: meperidine (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.3–5.5); long-acting (OR: 5.4; 95% CI: 1.0–29.2) and short-acting (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.1–6.5) benzodiazepines | |

| Retrospective comparative studies | ||||||

| Ilahi et al. [19] | Confusion (not specified) | Not specified | 8% | 23% | Higher incidence of confusion with epidural morphine (p = 0.019) | |

* Values are expressed as mean, with range in parentheses; NR = not reported; GA = general anesthesia; PCEA= patient-controlled epidural anesthesia; IV = intravenous; PCA = patient-controlled anesthesia; FNB = femoral nerve block; IM = intramuscular; MMSE = Mini Mental Status Examination; SPMSQ = Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; CAM = Confusion Assessment Method; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; POD = postoperative day; OR= odds ratio; preop = preoperatively; postop = postoperatively.

When narcotic medications were used, morphine and meperidine appeared to be associated with an increased risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, irrespective of the mode of administration (IV, intramuscular [IM], or epidural). Inan et al. [20] found no difference in postoperative cognitive dysfunction with the use of epidural versus IV PCA morphine and Colwell and Morris [7] reported no difference in complications, including confusion, with the use of IV PCA versus IM morphine postoperatively. However, Hartrick et al. [16] and Herrick et al. [18] reported a higher incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction with the use of morphine PCA as compared to fentanyl PCA, and Ilahi et al. [19] found a higher incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction with the use of continuous epidural morphine as compared to fentanyl (23% versus 8%; p = 0.019). Leung et al. [29] found that IV PCA was associated with a higher risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction as compared to oral narcotics (odds ratio [OR]: 3.75; 95% CI: 1.27–11.01), as was postoperative benzodiazepine use (OR: 2.29; 95% CI: 1.21–4.36). Marcantonio et al. [33] reported similar increased risk for delirium with the use of either long- or short-acting benzodiazepines, as well as both epidural and IV meperidine.

These findings are, however, tempered by the fact that nine of the 12 studies did not report any details on how confusion and/or delirium were defined and diagnosed [7, 15, 16, 18–20, 27, 34], and no studies appeared to assess the rate of postoperative cognitive dysfunction beyond discharge from hospital.

Discussion

Surgeons and healthcare organizations continue to be pressured to increase the efficiency of care associated with elective joint arthroplasty, as well as to further reduce the incidence of adverse events. While a number of advances have been made in both intra- and postoperative pain management techniques during joint arthroplasty, and while the effectiveness of various modalities on pain control and postoperative mobilization have been extensively studied, less is known about the impact on postoperative cognitive dysfunction, which remains one of the more common adverse events after TKA and THA. For this reason, we undertook the present systematic review to assess the current state of knowledge concerning the association between anesthesia and pain management strategies and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. We found that general anesthesia may be associated with early postoperative cognitive dysfunction, with no effect seen beyond 7 days. Optimization of depth of sedation through the use of adjunct monitoring may also be beneficial, although evidence is limited. While multimodal anesthesia protocols themselves were not found to reduce the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, strategies that minimized the use of narcotic medications postoperatively did appear to be helpful.

We acknowledge several limitations of the present study. First, despite using a carefully constructed, inclusive, and systematic search strategy following generally accepted methodology, it is possible that we nevertheless failed to identify one or more studies that assessed the incidence or risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction associated with anesthetic and/or pain management techniques. This may especially be true for studies that did not have the assessment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction as a primary or secondary outcome measure but nevertheless reported it in the body of the text. Second, the reporting of results is limited by considerable heterogeneity in patient populations, methods of assessment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, anesthetic techniques, and time points of assessment. Furthermore, a number of the included studies did not specify what criteria were used for the diagnosis of confusion and/or cognitive dysfunction. Together, these variations rendered quantitative analysis of aggregated results (as one might do in a formal meta-analysis) impossible. Nevertheless, given the considerable number of citations reviewed and the high proportion of prospective randomized studies included in the final review, we believe that our review does provide important insight into the questions posed at the study outset.

We identified several findings that will be of interest to surgeons and anesthesiologists alike. The available evidence suggests that general anesthesia is associated with increased rates of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the early postoperative period, although no differences were identified beyond Postoperative Day 7. Unfortunately, it was not possible to ascertain from the available evidence whether this difference is due to the anesthetic technique per se or to a potentially modifiable factor. Nevertheless, this finding further supports the overall trend toward the use of regional techniques for elective joint arthroplasty surgery, which has found favor in part due to benefits in terms of improved postoperative pain control and decreased nausea and vomiting [32]. In patients who are operated on under general anesthesia, the optimization of depth of sedation through the use of intraoperative cerebral EEG and regional oxygenation monitoring may decrease the frequency and severity of postoperative cognitive dysfunction up to 1 year postoperatively, although this finding was limited to a single study [4]. Similarly, attention should be paid to the depth of sedation provided as an adjunct to regional anesthesia. While not specifically addressed in any of the included studies, it is possible that excessive adjunct sedation may obviate some or all of the benefits of regional techniques in terms of reducing postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the early postoperative period. There is limited evidence supporting the impact of any other variations in general or regional anesthetic techniques on postoperative cognitive dysfunction. While little has been reported on the effects of multimodal anesthetic protocols on the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction per se, several studies comparing different postoperative pain management strategies showed benefit for individual components typically included in multimodal protocols. This includes avoiding narcotic use through the use of single-shot or continuous peripheral nerve blocks and/or NSAIDs. Additionally, when narcotic medications are used, surgeons and anesthesiologists should preferentially select nonmorphine agents and transition to oral narcotics as soon as possible to minimize the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

While many of the anesthetic and pain management strategies identified in our review may be beneficial in terms of reducing the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, it is important to recognize that the included studies may not have assessed potential risks with their use that are relevant to patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. For example, while continuous-infusion peripheral nerve catheters may be beneficial in terms of reducing the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction (potentially because of decreased narcotic requirements), several authors have noted an increased incidence of complications, including muscle weakness and falls, with the use of this technique [23, 25]. Given the importance of early mobilization after total joint arthroplasty and the potentially catastrophic consequences with a fall in this context, continuous peripheral nerve blockades should be used with caution. Similarly, while the routine use of both IV and oral NSAIDs may be of benefit, the risks of major gastrointestinal complications, including fatal hemorrhage, may not be trivial in certain patient populations [5, 13]. For this reason, it is important that decisions concerning the optimal anesthetic and postoperative pain management regimens be made by surgeons, anesthesiologists, and patients together to appropriately weigh the spectrum of potential benefits and risks with different modalities.

Given the increasing use of hip and knee arthroplasty in younger populations and the resultant trend toward a wider age distribution for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty [28, 40, 43], different anesthetic and pain management techniques may be appropriate in different patient populations based on the patient-specific risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction. It is well documented in the general surgical population that certain patient factors such as older age and preexisting cognitive impairment increase the risk of perioperative delirium [6, 8, 9, 31], and these patients in particular may benefit from the use of anesthetic techniques that emphasize minimization of the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Additionally, other factors such as visual or hearing impairment, the use of restraints, dehydration, and administration of medications such as centrally acting antihistamines or benzodiazepines have been associated with an increased risk for delirium in a variety of hospitalized patient populations, and appropriate management of these factors should be incorporated into clinical care pathways. Nevertheless, further work is needed to better define and quantify potential risk factors for postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients scheduled to undergo elective joint arthroplasty procedures and to assess the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of different anesthetic and pain management strategies based on preoperative risk stratification.

In summary, both anesthetic and pain management strategies do appear to influence the risk of cognitive dysfunction after elective joint arthroplasty. Despite the substantial number of prospective randomized studies found, the wide variety of anesthetic techniques and analgesic regimens used in the reviewed studies, as well as the variability in methodology used to diagnose postoperative cognitive dysfunction and the assessment time points, limits interpretation of the results. However, while the evidence available to date is quite heterogeneous, it does suggest that the optimal strategy includes the use of regional anesthesia, combined with multimodal techniques that minimize the need for postoperative narcotics in general, and especially avoiding the use of nonoral narcotics or morphine in any form. The authors strongly encourage other investigators to adopt the use of widely accepted, validated tools for the assessment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Additionally, detailed reporting of the potential risk factors and the anesthetic and analgesic techniques will facilitate future meta-analyses that can adequately control for the wide range of potential factors affecting the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and help better define optimal anesthetic and pain management strategies for elective joint arthroplasty.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancelin ML, de Roquefeuil G, Ledesert B, Bonnel F, Cheminal JC, Ritchie K. Exposure to anaesthetic agents, cognitive functioning and depressive symptomatology in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:360–366. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anwer HM, Swelem SE, El Sheshai A, Moustafa AA. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction in adult and elderly patients—general anesthesia vs subarachnoid or epidural analgesia. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2006;18:1123–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballard C, Jones E, Gauge N, Aarsland D, Nilsen OB, Saxby BK, Lowery D, Corbett A, Wesnes K, Katsaiti E, Arden J, Amoako D, Prophet N, Purushothaman B, Green D. Optimised anaesthesia to reduce post operative cognitive decline (POCD) in older patients undergoing elective surgery, a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellsague J, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, Varas-Lorenzo C, Fourrier-Reglat A, Nicotra F, Sturkenboom M, Perez-Gutthann S. Individual NSAIDs and upper gastrointestinal complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies (the SOS project) Drug Saf. 2012;35:1127–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF03261999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaput AJ, Bryson GL. Postoperative delirium: risk factors and management: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:304–320. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colwell CW, Jr, Morris BA. Patient-controlled analgesia compared with intramuscular injection of analgesics for the management of pain after an orthopaedic procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:726–733. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contin AM, Perez-Jara J, Alonso-Contin A, Enguix A, Ramos F. Postoperative delirium after elective orthopedic surgery. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:595–597. doi: 10.1002/gps.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1578–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deiner S, Silverstein JH. Postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103(suppl 1):i41–i46. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deo H, West G, Butcher C, Lewis P. The prevalence of cognitive dysfunction after conventional and computer-assisted total knee replacement. Knee. 2011;18:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Galinski D, Pulido C, Real J, Rodriguez A, Puig MM. Comparison of two protocols using low doses of bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia during joint replacement in elderly patients. Pain Clinic. 2005;17:15–24. doi: 10.1163/1568569053421672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994;343:769–772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ghoneim MM, Hinrichs JV, O’Hara MW, Mehta MP, Pathak D, Kumar V, Clark CR. Comparison of psychologic and cognitive functions after general or regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:507–515. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198810000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal N, McKenzie J, Sharkey PF, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ, Austin MS. The 2012 Chitranjan Ranawat Award. Intraarticular analgesia after TKA reduces pain: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:64–75. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartrick CT, Bourne MH, Gargiulo K, Damaraju CV, Vallow S, Hewitt DJ. Fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system for acute-pain management after orthopedic surgery: a comparative study with morphine intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebl JR, Kopp SL, Ali MH, Horlocker TT, Dilger JA, Lennon RL, Williams BA, Hanssen AD, Pagnano MW. A comprehensive anesthesia protocol that emphasizes peripheral nerve blockade for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(suppl 2):63–70. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrick IA, Ganapathy S, Komar W, Kirkby J, Moote CA, Dobkowski W, Eliasziw M. Postoperative cognitive impairment in the elderly: choice of patient-controlled analgesia opioid. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:356–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb07748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilahi OA, Davidson JP, Tullos HS. Continuous epidural analgesia using fentanyl and bupivacaine after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inan N, Cakan T, Ozen M, Aydin N, Gurel D, Baltaci B. The effect of opioid administration by different routes on the psychological functions of elderly patients. Agri. 2007;19:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson RL, Kopp SL, Hebl JR, Erwin PJ, Mantilla CB. Falls and major orthopaedic surgery with peripheral nerve blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:518–528. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones MJ, Piggott SE, Vaughan RS, Bayer AJ, Newcombe RG, Twining TC, Pathy J, Rosen M. Cognitive and functional competence after anaesthesia in patients aged over 60: controlled trial of general and regional anaesthesia for elective hip or knee replacement. BMJ. 1990;300:1683–1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6741.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandasami M, Kinninmonth AW, Sarungi M, Baines J, Scott NB. Femoral nerve block for total knee replacement—a word of caution. Knee. 2009;16:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kudoh A, Takase H, Takazawa T. A comparison of anesthetic quality in propofol-spinal anesthesia and propofol-fentanyl anesthesia for total knee arthroplasty in elderly patients. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langford RM, Joshi GP, Gan TJ, Mattera MS, Chen WH, Revicki DA, Chen C, Zlateva G. Reduction in opioid-related adverse events and improvement in function with parecoxib followed by valdecoxib treatment after non-cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:577–590. doi: 10.2165/11317570-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leskinen J, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Paavolainen P, Remes V. The incidence of knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis grows rapidly among baby boomers: a population-based study in Finland. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:423–428. doi: 10.1002/art.33367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung JM, Sands LP, Vaurio LE, Wang Y. Nitrous oxide does not change the incidence of postoperative delirium or cognitive decline in elderly surgical patients. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:754–760. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lie SA, Pratt N, Ryan P, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Graves S. Duration of the increase in early postoperative mortality after elective hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:58–63. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Losina E, Thornhill TS, Rome BN, Wright J, Katz JN. The dramatic increase in total knee replacement utilization rates in the United States cannot be fully explained by growth in population size and the obesity epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:201–207. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macfarlane AJ, Prasad GA, Chan VW, Brull R. Does regional anaesthesia improve outcome after total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:335–345. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Ludwig LE, Lind L, Katz N, Cook EF, Orav EJ, Lee TH. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA. 1994;272:1518–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520190064036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marino J, Russo J, Kenny M, Herenstein R, Livote E, Chelly JE. Continuous lumbar plexus block for postoperative pain control after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:29–37. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielson WR, Gelb AW, Casey JE, Penny FJ, Merchant RN, Manninen PH. Long-term cognitive and social sequelae of general versus regional anesthesia during arthroplasty in the elderly. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:1103–1109. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters CL, Shirley B, Erickson J. The effect of a new multimodal perioperative anesthetic regimen on postoperative pain, side effects, rehabilitation, and length of hospital stay after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Postler A, Neidel J, Gunther KP, Kirschner S. Incidence of early postoperative cognitive dysfunction and other adverse events in elderly patients undergoing elective total hip replacement (THR) Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen LS, Johnson T, Kuipers HM, Kristensen D, Siersma VD, Vila P, Jolles J, Papaioannou A, Abildstrom H, Silverstein JH, Bonal JA, Raeder J, Nielsen IK, Korttila K, Munoz L, Dodds C, Hanning CD, Moller JT. Does anaesthesia cause postoperative cognitive dysfunction? A randomised study of regional versus general anaesthesia in 438 elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:260–266. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen LS, Schmehl W, Jakobsson J. Comparison of xenon with propofol for supplementary general anaesthesia for knee replacement: a randomized study. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:154–159. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez RA, Tellier A, Grabowski J, Fazekas A, Turek M, Miller D, Wherrett C, Villeneuve PJ, Giachino A. Cognitive dysfunction after total knee arthroplasty: effects of intraoperative cerebral embolization and postoperative complications. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Review articles: postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1202–1211. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skytta ET, Jarkko L, Antti E, Huhtala H, Ville R. Increasing incidence of hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in 30- to 59-year-old patients. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:1–5. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.548029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinmetz J, Funder KS, Dahl BT, Rasmussen LS. Depth of anaesthesia and post-operative cognitive dysfunction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Mattis S, Szatrowski TP, Charlson ME. Cognitive effects after epidural vs general anesthesia in older adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1995;274:44–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530010058035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams-Russo P, Urquhart BL, Sharrock NE, Charlson ME. Post-operative delirium: predictors and prognosis in elderly orthopedic patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:759–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong J, Song D, Blanshard H, Grady D, Chung F. Titration of isoflurane using BIS index improves early recovery of elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgeries. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:13–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03020413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.YaDeau JT, Cahill JB, Zawadsky MW, Sharrock NE, Bottner F, Morelli CM, Kahn RL, Sculco TP. The effects of femoral nerve blockade in conjunction with epidural analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:891–895. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000159150.79908.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]