Abstract

Purpose

The failure of total hip systems caused by wear-particle-induced loosening has focused interest on factors potentially affecting wear rate. Remnants of the blasting material were reported on grit-blasted surfaces for cementless fixation. These particles are believed to cause third-body wear and implant loosening. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the early clinical and radiological outcomes of a cementless hip system with a new, contamination-free, roughened surface with regard to prosthesis-related failures.

Methods

Between May 2004 and March 2009, 202 consecutive primary total hip arthroplasties (THAs) (192 patients with a mean age of 62.6 years) were performed using a cementless stem (Hipstar®) and a hemispherical acetabular cup (Trident®).

Results

At a minimum follow-up of two years, five revisions (2.5 %) due to aseptic loosening of the stem and three (1.5 %) of the cup were necessary. The cumulative rate of prostheses survival, counting revision of both components and with aseptic failure as end point, was 92.9 % at 8.8 years. Radiolucent lines up to three millimetres were evaluated in the proximal part of the femur in 61 % of cases.

Conclusions

Although the incidence of radiolucent lines was decreased, the revision rate was considerably increased compared to other uncemented hip implants with grit-blasted surfaces in the short- to mid-term follow-up of our study. Subsequent studies are needed to confirm whether these changes in implant material and surface affect the radiological and clinical outcome in the long term.

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Cementless stem, Contamination-free surface, Radiographic analysis, Clinical outcome

Introduction

Optimal fixation of cementless hip stems is essential for long-term stability. The failure of total hip systems caused by wear-particle-induced loosening has focused interest on factors potentially affecting wear rate. In addition to the introduction of new wear-resistant materials in tribological pairing, new techniques of implant fixation have been developed. Cementless fixation of implants into the bone avoids the release of cement particles and has been broadly used for many decades [1–5]. Standard surface-finishing processes use ceramic or glass particles to roughen the implant. In recent years, remnants of the blasting material (produced by grit-blasting) have been reported on cementless fixation surfaces [6–8]. There have been reports of these particles remaining embedded on the finished product surface and being released into the joint, thus generating third-body wear [9, 10]. The evaluation of third-body wear for total hip arthroplasty (THA) in vivo can be done by measuring the roughness of the femoral head and the increased total wear rate [11, 12].

The European Committee for Standardisation, EN clause 8, decided that the surfaces of metallic components shall be free of imperfections that would impair the function of the implant and shall additionally be free of embedded or deposited finishing materials or contaminants. To achieve this, components shall be cleaned, degreased, rinsed, and dried. All polishing operations shall be performed using an iron-free medium.

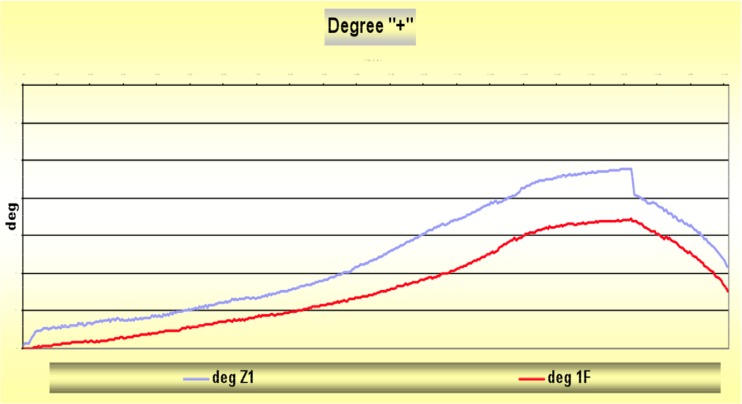

The objective of a newly designed femoral stem was to achieve optimal primary and secondary stability by providing a small, rectangular cross section for optimal endosteal blood circulation and a rough surface without grit-blasted particles for improved osseous integration. Since the end of 2003, the Hipstar® stem (Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) has been produced with this new surface treatment. In this process, a contamination-free surface on the prosthesis with homogeneous roughness (average Ra = 5.6 μm, maximum Rt = 55 μm) is achieved. The major steps of the process are iron-grit blasting, surface-blow cleaning, acid cleaning, tap and distilled water rinsing and air-blow drying. This process is designed to remove residual blasting media, a method not feasible with conventional ceramic-type grit. It has been shown that this process promotes bone formation and results in better osseous integration [13, 14]. The stem is made of titanium–molybdenum–zirconium–iron alloy (TMZF®), a beta-titanium alloy containing no aluminium oxide (Al2 O3) [15]. The improved fatigue strength of the TMZF® alloy allows a smaller neck diameter, which increases the range of motion (ROM) in the artificial hip joint. This reduces the risk of impingement, wear, subluxation and dislocation [16]. Compared with the established Zweymüller Alloclassic® stem, the design of the Hipstar® stem with a 1-mm rectangular cross section and a lateral fin improves the primary rotational stability, which could be verified in fresh–frozen cadaver femora in our biomechanical test laboratory (Fig. 1). Prymka et al. [17] found a significantly higher rotational primary stability of the Hipstar® stem in vitro. A better osseous integration with the particle-free surface and a higher primary stability by innovation in design can be expected to significantly reduce radiolucent lines (RLs) and was identified in the study.

Fig. 1.

Primary rotational stability of the Hipstar® stem (deg 1 F) was significantly improved compared to the Zweymüller Alloclassic® stem (deg Z1) at 30-nm rotational load using a hydraulic axial and torsional testing system (MTS 858 MiniBionix® II) in our laboratory for biomechanics

The purpose of this study was to evaluate a possible impact of this new surface on clinical and radiological outcome after a short- to midterm period. The hypothesis was that this type of artificial hip joint improves clinical and radiographic outcome, with decreased wear and a reduced number of aseptic loosening compared with other types of implants.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

We retrospectively evaluated the prospectively collected data of 192 consecutive patients (202 hips) undergoing uncemented primary THA between May 2004 and March 2009 with the Hipstar® stem (Stryker, Duisburg, Germany), with a rectangular cross-section design and a new contamination-free, roughened surface. Between May 2004 and October 2006, we used hemispherical acetabular cups (Trident PSL®); since then, threaded cups (Trident® TC) were used instead of the press-fit cup in 92 cases. In all cases, alumina ceramic (Biolox® forte) liner and femoral heads (Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) with a diameter between 28 and 36 mm were used. The mean follow-up period was 3.4 years. There were 103 female and 89 male patients, with an average age of 62.6 years and a primary diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis, secondary osteoarthritis, femoral-head osteonecrosis or rheumatoid arthritis. Patient characteristics and implant-related data are shown in Table 1. Exclusion criteria were severe developmental hip dysplasia with fixation disability of the hemispherical acetabular cup, infections and malignant tumors in the patient history. All operations were performed by experienced orthopaedic surgeons (minimum years of experience in THA) using a lateral, transgluteal approach. All acetabular and femoral components were cementless. The surgeon aimed to position the acetabular cup at abduction of 40° ± 10° and anteversion of 15° ± 10°, as suggested by Lewinnek et al. [18]. Ten patients underwent bilateral hip reconstruction, two in a single session; the remainder had the second hip replaced within one to two years. Antibiotic prophylaxis was maintained for 48 hours postoperatively. Thromboembolic prophylaxis was through elastic stockings on the operated leg and low-molecular-weight heparin for six weeks. Prevention of heterotopic bone formation was achieved by indomethacin or postoperative irradiation. Patients were instructed to walk with partial weight bearing with the aid of two crutches for six weeks after surgery. Each participating institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, and all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Table 1.

Demographic data and implant-related data at the time of operation

| Demographic and implant-related data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (range) | Number (%) | ||

| Number of cases / patients | 202/192 | ||

| Age (years) | 64.4 (20–89) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 76 (72–80) | ||

| Sex | m | 87 (43) | |

| w | 115 (57) | ||

| Stem.size | 0 | 0.5 | |

| 1 | 4.7 | ||

| 2 | 14.6 | ||

| 3 | 19.3 | ||

| 4 | 19.3 | ||

| 5 | 19.8 | ||

| 6 | 10.4 | ||

| 7 | 5.7 | ||

| 8 | 5.7 | ||

| Head.size | 28 | 6.8 | |

| 32 | 56.8 | ||

| 36 | 36.5 | ||

| Cup.size | 48 | 14 | |

| 50 | 20 | ||

| 52 | 10 | ||

| 54 | 20 | ||

| 56 | 14 | ||

| 58 | 14 | ||

| 60 | 4 | ||

| 61 | 2 | ||

| 62 | 2 | ||

Clinical and radiographic follow-up

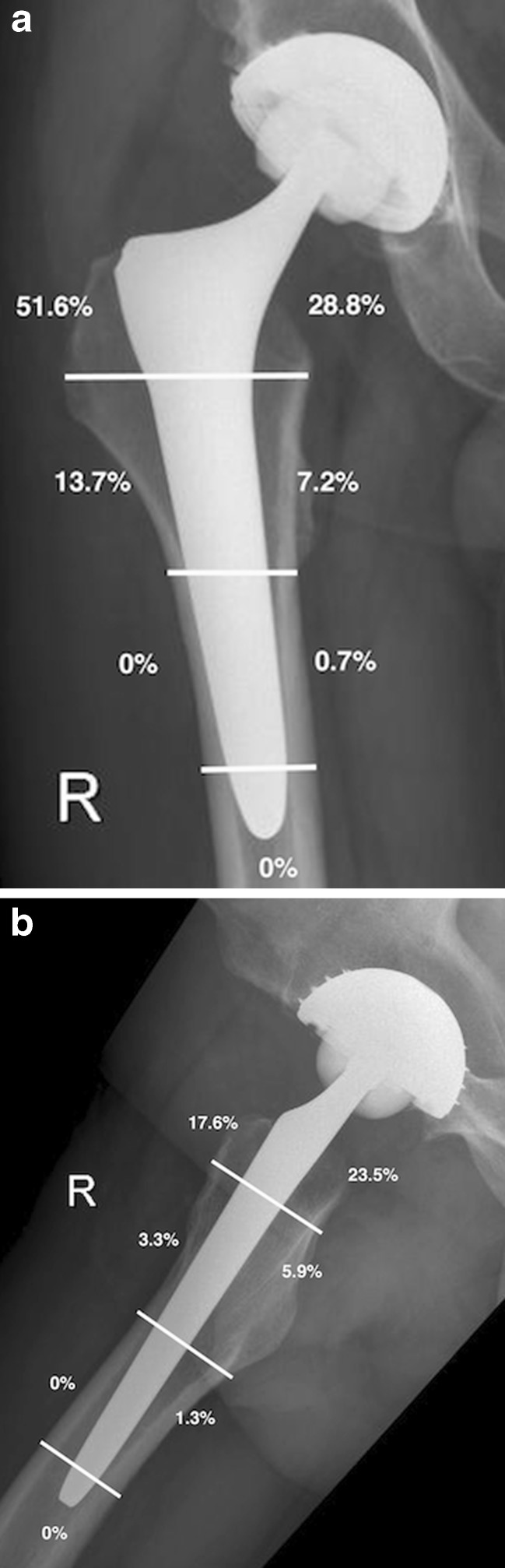

Clinical and radiographic evaluation was performed preoperatively, and postoperatively at six weeks, three, six and 12 months and annually thereafter. At two years of follow-up, 34 patients (16.8 %), who did not want to participate in the follow-up examinations due to the distance from the hospital were lost. Fifteen patients (7.4 %) died of other causes not related to THA. Clinical evaluation included physical examination of ROM and Harris Hip Score (HHS) [19]. After excluding revision cases, radiological results of 153 hips were available at the last examination. Standard radiographs included an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and anteroposterior and lateral views of the hip. A single observer uninvolved in the implantation procedure evaluated all radiographs using the scales on a Patient Archive Computer System (PACS) workstation (Agfa HealthCare GmbH, Bonn, Germany). Radiolucencies with respect to the stem were classified according to the system of Gruen et al. [20] on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs (Fig. 2); acetabular components were assessed according to DeLee and Charnley [21] on anteroposterior radiographs. Radiolucencies at the bone–prosthesis interface were recorded as less than one millimetre, between one and three millimetres or more than three millimetres in width.

Fig. 2.

Postoperative radiographs showing radiolucent lines (a) in the anteroposteriorer view (Gruen zones 1–7) and (b) in the lateral view (Gruen zones 8–14)

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0 (SPSS Inc./IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate implant survival probabilities, counting revision of the stem and/or cup for aseptic failure and for any reason as the terminating event and censoring patients at the time of their death or at the end of the follow-up period. Normally distributed preoperative and postoperative data (HHS, ROM) were compared using a t test for paired samples, with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Revisions and complications

At a mean follow-up of 3.4 years, we detected 12 complications causing revisions (6 %): five stem loosenings (2.5 %), three cup loosenings (1.5 %), two infections (1 %), one periprosthetic fracture (0.5 %) and one recurrent dislocation (0.5 %). The revision rate due to aseptic loosening of both implant components (stem and cup) was 4 %. Intraoperative complications occurred in three cases: two sciatic nerve lesions with recovery, and one femoral fracture.

Clinical results

In clinical examinations, mean preoperative HHS was 47.1[range 19–74, standard deviation (SD) 13.3]; after 12 months, 92.8 (50–100, SD 10.5, p < 0.001), and after 24 months 93.2 (63–100, SD 10.3, p < 0.001). Mean flexion of the hip joint improved from 75° before the operation to 105° 24 months postoperatively (p < 0.001).

Radiological results

After excluding revision cases, radiological results of 153 cases at the last examination (mean follow-up 3.4 years) showed RLs of under one millimetre in 67 cases (42.5 %), between one and three millimetres in 27 cases (18.3 %) and none over three millimetres in width. In the anteroposterior view, 79 %, and in the lateral view, 80 % of RLs were seen in the proximal part of the hip stem (Gruen zones 1, 7, 8, 14, Fig. 2a, b). An RL adjacent to the acetabular component was seen in zones I and II of DeLee and Charnley in three hips (1.9 %) and in zone III in four hips (2.5 %). No progression was seen at the further investigations. Osteolysis in terms of a sharp demarcated radiolucent space with a rounded or scalloped appearance extending away from the implant was not detected around any stem or cup.

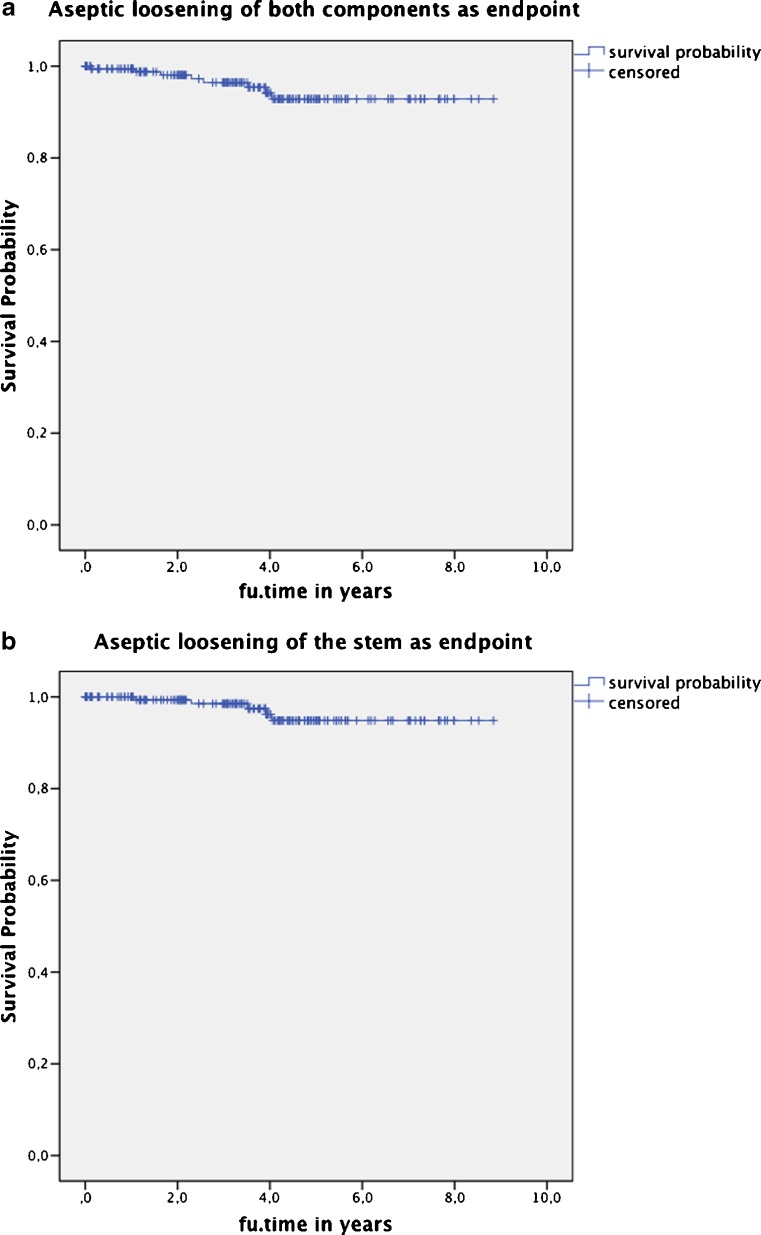

Survival analysis

The cumulative rate of the prostheses survival, counting revision of both components with aseptic failure as the end point, was 92.9 % at 8.8 years. The cumulative survival rate with aseptic failure of the stem as the endpoint was 94.9 % and of the cup 97.9 % (Fig. 3a, b). The probability of a revision-free implant survival with revision for any reason as the endpoint was 87.2 % at 8.8 years.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative survival rate (a) counting revision of both components with aseptic failure as the end point was 92.9 %, (b) with aseptic failure of the stem as the endpoint was 94.9 % at 8.8 years

Discussion

The failure of total hip systems caused by wear-particle-induced loosening has focused interest on factors potentially affecting wear rate. Cementless fixation of implants into the bone avoids the release of cement particles and has been broadly used for many decades. Ten to 20 % of the surface of roughened cementless stems is contaminated with sharp particles from blasting media (alumina, glass, etc.) [6–8]. These particles can detach and migrate into the artificial joint, causing damage to the femoral head and/or increased wear [9, 10]. Cell attachment to the stem surface is compromised, as they do not respond to the grit. Recent scientific discussion is focussing on this issue as a potential cause for early loosening. Surface roughness and clean surfaces promote cell adhesion and bone proliferation, whereas embedded alumina—silicate particles depress bone proliferation. Therefore, clean and rough surfaces are the best option for bone proliferation [22].

Since the end of 2003, the Hipstar® stem has been produced with a new surface treatment, which achieves a contamination-free surface on the prosthesis with a homogeneous roughness. We addressed the question of whether the use of stems with this new surface has a clinical and radiological benefit. Early radiological results indicate that the Hipstar® stem, showing RLs in about 61 % of cases, may result in higher primary and secondary stability by enhanced osseous integration than the well-established stems, such as the straight Zweymüller stem (SL-Plus®, RLs in 87 %) [23]. According to Huiskes [24] and Bugbee et al. [25], RLs are signs of stress shielding, which can lead to aseptic implant loosening. Nevertheless, several long-term studies relating to the second-generation Zweymüller stem, known as the Alloclassic® stem, have failed to confirm that these radiological changes have clinical relevance for aseptic loosening [3, 26].

Early clinical results in our study population are similar; however, the revision rate is increased compared with other established cementless hip implants [2, 3, 27–29]. In our study population (202 cases), we recorded five stem revisions (2.5 %) and three cup revisions (1.5 %) due to aseptic loosening at a mean follow-up of 3.4 years. In the study by Grubl et al. [3], the cumulative rate of survival with femoral revision as the end point was 99 % at ten years, 98 % at 15 years and 96 % at 20 years [27]. The Zweymüller Alloclassic® stem used in this study is a grit-blasted titanium alloy. It has a similar rectangular design, which differs only slightly in external shape from the Hipstar® stem. The surface features the same range of roughness (within 3–6 μm), but the surface of the Hipstar® stem is free of grit-blasted particles. Although Racey et al. [14] reported that this provides better osseous integration and Prymka et al. [17] found a significantly higher primary rotational stability of the Hipstar® stem in vitro, we were unable to detect this potential advantages in our study cohort. The cumulative rate of survival with femoral revision as the end point at 8.8 years was 94.9 % in our study. Our findings are limited by the nature of the study, which was an uncontrolled, observational study with pre–post comparisons of the cementless Hipstar® system within one centre. Another limitation is the high number of patients lost to follow-up (16.8 %).

In conclusion, use of the cementless Hipstar® stem with the new contamination-free surface improved early radiological results. We identified a reduction of RLs of >20 % compared with other cementless straight stems. However, we found inferior results with regard to prosthesis-related failures, showing revision rates of 4 % due to aseptic loosening of the implant at short- to midterm follow-up. Subsequent studies must be performed to determine whether these results have radiological or clinical relevance in the long term.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Della Valle CJ, Mesko NW, Quigley L, Rosenberg AG, Jacobs JJ, Galante JO. Primary total hip arthroplasty with a porous-coated acetabular component. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of twenty years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1130–1135. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi R, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Hydroxyapatite coated femoral stems in primary total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubl A, Chiari C, Giurea A, Gruber M, Kaider A, Marker M, Zehetgruber H, Gottsauner-Wolf F. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with the rectangular titanium Zweymuller stem. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of fifteen years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2210–2215. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwartele R, Peters A, Brouwers J, Olsthoorn P, Brand R, Doets C. Long-term results of cementless primary total hip arthroplasty with a threaded cup and a tapered, rectangular titanium stem in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 2008;32:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kress AM, Schmidt R, Holzwarth U, Forst R, Mueller LA. Excellent results with cementless total hip arthroplasty and alumina-on-alumina pairing: minimum ten-year follow-up. Int Orthop. 2011;35:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1150-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubl A, Kolb A, Reinisch G, Fafilek G, Skrbensky G, Kotz R. Characterization, quantification, and isolation of aluminum oxide particles on grit blasted titanium aluminum alloy hip implants. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;83:127–131. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuh A, Uter W, Holzwarth U, Kachler W, Goske J, Muller T. The use of a thermomechanical cleaning procedure for removal of residual particles of corund blasted or glass bead peened implants in total hip arthoplasty. Zentralbl Chir. 2005;130:346–352. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-836801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wick M, Lester DK. Radiological changes in second- and third-generation Zweymuller stems. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1108–1114. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B8.14732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohler M, Kanz F, Schwarz B, Steffan I, Walter A, Plenk H, Jr, Knahr K. Adverse tissue reactions to wear particles from Co-alloy articulations, increased by alumina-blasting particle contamination from cementless Ti-based total hip implants. A report of seven revisions with early failure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:128–136. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B1.11324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer TW, Taylor SK, Jiang M, Medendorp SV. An indirect comparison of third-body wear in retrieved hydroxyapatite-coated, porous, and cemented femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;298:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raimondi MT, Vena P, Pietrabissa R. Quantitative evaluation of the prosthetic head damage induced by microscopic third-body particles in total hip replacement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58:436–448. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinisch G, Judmann KP, Lhotka C, Lintner F, Zweymuller KA. Retrieval study of uncemented metal-metal hip prostheses revised for early loosening. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trentani L, Pelillo F, Pavesi FC, Ceciliani L, Cetta G, Forlino A. Evaluation of the TiMo12Zr6Fe2 alloy for orthopaedic implants: in vitro biocompatibility study by using primary human fibroblasts and osteoblasts. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2863–2869. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Racey SN MA, Jones E, Birch AW. Iron and alumina grit blasted TMFZ alloys differentially regulate bone formation in vitro. Eur Cells Mater. 2004;7(1):81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuh A, Holzwarth U, Kachler W, Goske J, Zeiler G. Surface characterization of Al2O3-blasted titanium implants in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopade. 2004;33:905–910. doi: 10.1007/s00132-004-0663-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler O, Patil S, Wirth S, Mayr E, Colwell CW, Jr, D’Lima DD. Bony impingement affects range of motion after total hip arthroplasty: a subject-specific approach. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:443–452. doi: 10.1002/jor.20541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prymka M, Vogiatzis M, Hassenpflug J. Primary rotatory stability of hip endoprostheses stems after manual and robot assisted implantation. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2004;142:303–308. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinnek GE, Lewis JL, Tarr R, Compere CL, Zimmerman JR. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao L, Lawrence J, Phua YF, Chian KS, Lim GC, Zheng HY. Enhanced human osteoblast cell adhesion and proliferation on 316 LS stainless steel by means of CO2 laser surface treatment. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;73:148–156. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergschmidt P, Bader R, Finze S, Gankovych A, Kundt G, Mittelmeier W. Cementless total hip replacement: a prospective clinical study of the early functional and radiological outcomes of three different hip stems. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0907-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huiskes R. Stress shielding and bone resorption in THA: clinical versus computer-simulation studies. Acta Orthop Belg. 1993;59(Suppl 1):118–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bugbee WD, Culpepper WJ, 2nd, Engh CA, Jr, Engh CA., Sr Long-term clinical consequences of stress-shielding after total hip arthroplasty without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1007–1012. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zweymuller KA, Schwarzinger UM, Steindl MS. Radiolucent lines and osteolysis along tapered straight cementless titanium hip stems: a comparison of 6-year and 10-year follow-up results in 95 patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:871–876. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb A, Grubl A, Schneckener CD, Chiari C, Kaider A, Lass R, Windhager R. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with the rectangular titanium Zweymuller stem: a concise follow-up, at a minimum of twenty years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1681–1684. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hailer NP, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:34–41. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swamy G, Pace A, Quah C, Howard P. The Bicontact cementless primary total hip arthroplasty: long-term results. Int Orthop. 2012;36:915–920. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]