Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the risk factors of central lymph node metastasis of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Method: Published articles about papillary thyroid microcarcinoma were searched in PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE until October 2013 to examine the risky factors of central lymph node metastasis. Software RevMan 5.0 was used for meta-analysis. Results: Within the patients suffering papillary thyroid microcarcinoma underwent thyroidectomy plus prophylactic central lymph node dissection, tumor size, multifocality and capsular invasion have statistically relevant association with central lymph node metastasis, but no relation was observed associated with sex and age. Conclusion: The papillary thyroid microcarcinoma should be considered central lymph node metastasis when tumor size ≥0.5 cm, multifocality and have capsular invasion.

Keywords: Risk factors, central lymph node metastasis, papillary thyroid carcinoma

Introduction

Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC), which is defined as a papillary carcinoma measuring equal or less than 10 mm in diameter according to the World Health Organization classification [1]; PTMC accounts for 38.5% of papillary thyroid cancers in the United States, 35.7% in Shanghai, China; however, it up to 48.8% in France [2-8]. Currently the surgical approach of total – thyroidectomy plus prophylactic central lymph node dissection for PTMC is still controversial and uncertain [4,6]. And lymph node metastasis especially central lymph node metastasis is considered to be one of the most important risk factors associated with recurrence [9,10]. Therefore, it is necessary for surgeons to assess clinical features related to central lymph node metastasis of PTMC before surgery.

Materials and methods

The literature was retrieved using PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE and WANFANG until October 2013 and aided by manual searching and reference backtracking. The terms “papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, occult thyroid cancer” and “central or level VI lymph node dissection or metastasis” were used as the keyword. Central lymph node dissection means dissection of the level VI lymph node which lies in central position in the neck of PTMC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria: 1) published English literature, while original and review literature are not included; 2) study object patients with PTMC; 3) all the patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma underwent thyroidectomy plus prophylactic central lymph node dissection and 4) the experimental design was a retrospective clinical trial and the trial should provide complete data such as the number of cases.

Statistical analysis: We used RevMan 5.0 for meta-analysis. Before combined analysis, we assessed data heterogeneity among studies. A random-effects model was used When P<0.1, otherwise a fixed-model was applied. The odds ratio was calculated for dichotomous data along with 95% CI, the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Basic information

23 studies were finally obtained after a initial screening of the 234 literatures we had retrieved, further screened according to inclusion criteria (Figure 1), finally we included nine studies in our analysis [7,11-18]. All of our nine studies performed total thyroidectomy with prophylactic central neck dissection. Of these studies, three were carried out in China, four in Korea, one in Japan, and one in France. All nine studies included are retrospective trials including a total of 1928 patients. Basic information such as author, publication date, country, research design, number of cases and surgical approach is showed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for articles identified and included in the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Basic information of the studies

| Authors | Year | Country | Research design | Case number | Surgical approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lim [15] | 2009 | Korea | Retrospective clinical study | 86 | TT+PCLND |

| S. vergez [20] | 2010 | France | Retrospective clinical study | 82 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

| Zhao [7] | 2012 | China | Retrospective clinical study | 212 | TT+PCLND |

| Kim [16] | 2013 | Korea | Retrospective clinical study | 483 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

| So [17] | 2010 | Korea | Retrospective clinical study | 551 | TT+PCLND |

| Wada [12] | 2003 | Japan | Retrospective clinical study | 259 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

| Lee [13] | 2008 | Korea | Retrospective clinical study | 52 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

| Shao [18] | 2009 | China | Retrospective clinical study | 117 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

| Wang [19] | 2008 | China | Retrospective clinical study | 86 | TT or NTT+PCLND |

TT: total thyroidectomy, NTT: near-total thyroidectomy, PCLND: prophylactic central lymph node dissection.

Risk factors for central lymph node metastasis

Tumor size and central lymph node metastasis

Tumor size was reported in 8 studies, a random-effects model was adopted as there was a significant heterogeneity between tumor size <0.5 cm and tumor size >0.5 cm (P<0.00001, I2=81%). Tumor size >0.5 cm resulted in a higher incidence of central lymph node metastasis compared with Tumor size <0.5 cm (OR=2.31, 95% CI: 1.29-4.13; P=0.005; as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tumor size and central lymph node metastasis.

Foci number and central lymph node metastasis

Foci number was reported in 7 studies, a fix-effects model was adopted as there was no significant heterogeneity between unifocal and multifocal (P=0.40, I2=3%). T multifocal resulted in a higher incidence of central lymph node metastasis compared with unifocal (OR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.39-2.18; P<0.00001; as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Foci number and central lymph node metastasis.

Age and central lymph node metastasis

Age of PTMC was reported in 5 studies, a random-effects model was adopted as there was a significant heterogeneity between tumor age <45 years and age >45 years (P=0.09, I2=50%). No significant difference was observed between the age <45 years group and age >45 years group (OR=1.46, 95% CI: 0.93-2.31; P=0.10; as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Age and central lymph node metastasis.

Sex and central lymph node metastasis

Gender of PTMC was reported in 7 studies, a random-effects model was adopted as there was a significant heterogeneity between male ground and female group (P<0.00001, I2=88%). No significant difference was observed between the male ground and the female ground (OR=1.03, 95% CI: 0.40-2.67; P=0.96; as shown in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sex and central lymph node metastasis.

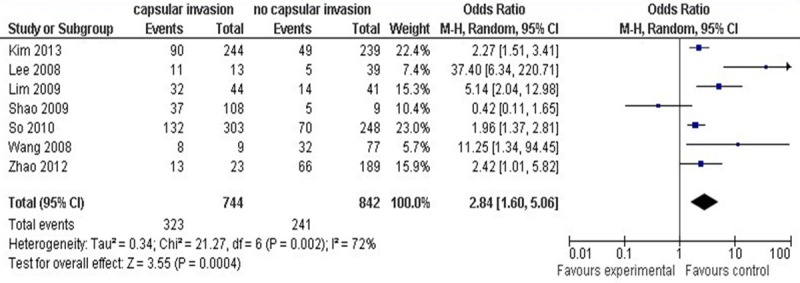

Capsulate invasion and central lymph node metastasis

Capsulate invasion of PTMC patients was reported in 7 studies, a random-effects model was adopted as there was a significant heterogeneity between capsulate invasion and non-capsulate invasion (P=0.002, I2=72%). Capsulate invasion resulted in a higher incidence of central lymph node metastasis compared with non-capsulate invasion (OR=2.84, 95% CI: 1.60-5.06; P=0.0004; as shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Capsulate invasion and central lymph node metastasis.

Discussion

Rates of extrathyroid extension, capsule invasion, lymph node metastases, and distant metastases at presentation in patients with PTMC have been as great as 21%, 20%, 26%, and 3%, respectively [19-21]. The incidence of CLNM in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma was reported from 31% to 61% [7,11,14]. In our studies, the frequency of LNM in PTMCs varied by ethnicity; the mean frequency in Asians was 38.2%, whereas in whites it was 47.6%.

It remains controversial whether patients with PTMC need PCLND or not. Some surgeons advocate that PCLND is not recommended in patients with PTMC for its less aggressive form and CLND may increase the rate of perioperative lesion such as hypoparathyroidism, laryngeal nerve injury [11,22,23]; While others suggest PCLND for it may reduce the recurrence rate and improve the survival [24-28]. And some clinical features for patients with PTMC are still much debated too. For example, zhao [7]’s results support the idea that age and gender are significantly different associated with CLNM; yet Lim [14] demonstrated that there are no statistically significant between age and gender with CLNM. Lee [13] found extracapsular spread was significantly associated with CLNM (p=0.14, OR=1.987); but zhao et al. [7] found that the difference between CLNM with or without capsular invasion (p=0.043, OR=2.4) was not so dramatic. Recent research has shown that tumors from multifocal PTC arise from independent clonal origins of distinct tumor foci [29]. And Pitt SC [30] have reported that in patients with primary tumors <1 cm even <0.5 cm, multifocal disease is a significant risk factor for contralateral tumors; but Lim YC [14] suggesting that central lymph node involvement is not associated with multifocality.

According to the above results and analysis, we found out that CLNM was significantly more likely to occur in patients with tumor size >0.5 cm, multifocality and capsular invasion, but there was no significant differences associated with sex and age. Central Lymph node metastasis are confirmed to be an independent and the most important predictors of disease relapse [20]. So prophylactic central lymph node dissection may be not recommended if the patients with clinicopathologic features such as tumor size <0.5 cm, tumor unifocality, no capsular invasion, but PCLND should be considered in patients with big tumor size (>0.5 cm), multifocal lesions or capsular invasion.

In general, this meta-analysis summarizes the common clinical factors to predict the risk of CLNM in patients with PTMC; however, there are still several limitations to this study. First of all, the studies we chose were not randomized case-control trial; so they only reflect PTMC patients with surgery approach of TT+PCLND. Furthermore, due to lacking follow-up data, only one study from Europe [13], more studies and researches are need to confirm CLNM model in PTMC patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Song Yuanchao from Department of Occupational and Environmental Health and Ministry of Education Key Lab of Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei 430030, China.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Sobin LH. Histological typing of thyroid tumours. Histopathology. 1990;16:513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin JD. Increased incidence of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with decreased tumor size of thyroid cancer. Med Oncol. 2010;27:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen AY, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States, 1988-2005. Cancer. 2009;115:3801–3807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giordano D, Gradoni P, Oretti G, Molina E, Ferri T. Treatment and prognostic factors of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol. 2010;35:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2010.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kutler DI, Crummey AD, Kuhel WI. Routine central compartment lymph node dissection for patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34:260–263. doi: 10.1002/hed.21728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrel R, Tripodi C, Cartier C, Makeieff M, Crampette L, Guerrier B. Cervical lymphadenopathies signaling thyroid microcarcinoma. Case study and review of the literature. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Q, Ming J, Liu C, Shi L, Xu X, Nie X, Huang T. Multifocality and total tumor diameter predict central neck lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:746–752. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang J, Wu Y, Li DS, Shen Q, Wang ZY, Sun TQ, An Y, Guan Q. New clinical features of thyroid cancer in eastern China. J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay ID, Hutchinson ME, Gonzalez-Losada T, McIver B, Reinalda ME, Grant CS, Thompson GB, Sebo TJ, Goellner JR. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 900 cases observed in a 60-year period. Surgery. 2008;144:980–987. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.035. discussion 987-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pisanu A, Reccia I, Nardello O, Uccheddu A. Risk factors for nodal metastasis and recurrence among patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: differences in clinical relevance between nonincidental and incidental tumors. World J Surg. 2009;33:460–468. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wada N, Duh QY, Sugino K, Iwasaki H, Kameyama K, Mimura T, Ito K, Takami H, Takanashi Y. Lymph node metastasis from 259 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: frequency, pattern of occurrence and recurrence, and optimal strategy for neck dissection. Ann Surg. 2003;237:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055273.58908.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, Lee SS, Jin SM, Kim JH, Rho YS. Predictive factors for central compartment lymph node metastasis in thyroid papillary microcarcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:659–662. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318161f9d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergez S, Sarini J, Percodani J, Serrano E, Caron P. Lymph node management in clinically node-negative patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim YC, Choi EC, Yoon YH, Kim EH, Koo BS. Central lymph node metastases in unilateral papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:253–257. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KE, Kim EK, Yoon JH, Han KH, Moon HJ, Kwak JY. Preoperative prediction of central lymph node metastasis in thyroid papillary microcarcinoma using clinicopathologic and sonographic features. World J Surg. 2013;37:385–391. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.So YK, Son YI, Hong SD, Seo MY, Baek CH, Jeong HS, Chung MK. Subclinical lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 551 resections. Surgery. 2010;148:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao Y, Cai XJ, Gao L, Li H, Xie L. [Clinical factors related to central compartment lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: clinical analysis of 117 cases] . Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;89:403–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Ji QH, Huang CP, Zhu YX, Zhang L. [Predictive factors for level VI lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma] . Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;46:1899–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow SM, Law SC, Chan JK, Au SK, Yau S, Lau WH. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid-Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and multifocality. Cancer. 2003;98:31–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegriti G, Scollo C, Lumera G, Regalbuto C, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Clinical behavior and outcome of papillary thyroid cancers smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter: study of 299 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3713–3720. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nam-Goong IS, Kim HY, Gong G, Lee HK, Hong SJ, Kim WB, Shong YK. Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of thyroid incidentaloma: correlation with pathological findings. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakorafas GH, Giotakis J, Stafyla V. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a surgical perspective. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:423–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwan WY, Chow TL, Choi CY, Lam SH. Complication rates of central compartment dissection in papillary thyroid cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ans.12343. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnet S, Hartl D, Leboulleux S, Baudin E, Lumbroso JD, Al Ghuzlan A, Chami L, Schlumberger M, Travagli JP. Prophylactic lymph node dissection for papillary thyroid cancer less than 2 cm: implications for radioiodine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1162–1167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tisell LE, Nilsson B, Molne J, Hansson G, Fjalling M, Jansson S, Wingren U. Improved survival of patients with papillary thyroid cancer after surgical microdissection. World J Surg. 1996;20:854–859. doi: 10.1007/s002689900130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YS, Kim SW, Kim SW, Kim SK, Kang HS, Lee ES, Chung KW. Extent of routine central lymph node dissection with small papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:1954–1959. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugitani I, Fujimoto Y. Symptomatic versus asymptomatic papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a retrospective analysis of surgical outcome and prognostic factors. Endocr J. 1999;46:209–216. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.46.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Gu J, Shang J, Wang K. Correlation analysis on central lymph node metastasis in 276 patients with cN0 papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:510–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shattuck TM, Westra WH, Ladenson PW, Arnold A. Independent clonal origins of distinct tumor foci in multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2406–2412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt SC, Sippel RS, Chen H. Contralateral papillary thyroid cancer: does size matter? Am J Surg. 2009;197:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]