Abstract

With advancing age, there is an increase in the complaints of a lack of a libido in women and erectile dysfunction in men. The efficacy of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, together with their minimal side effects and ease of administration, revolutionized the treatment of erectile dysfunction. For women, testosterone administration is the principal treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder. We sought to evaluate the use of androgens in the treatment of a lack of libido in women, comparing two periods, i.e., before and after the advent of the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. We also analyzed the risks and benefits of androgen administration. We searched the Latin-American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Cochrane Library, Excerpta Medica, Scientific Electronic Library Online, and Medline (PubMed) databases using the search terms disfunção sexual feminina/female sexual dysfunction, desejo sexual hipoativo/female hypoactive sexual desire disorder, testosterona/testosterone, terapia androgênica em mulheres/androgen therapy in women, and sexualidade/sexuality as well as combinations thereof. We selected articles written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish.

After the advent of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, there was a significant increase in the number of studies aimed at evaluating the use of testosterone in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. However, the risks and benefits of testosterone administration have yet to be clarified.

Keywords: Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological, Aging, Testosterone, Sexuality

INTRODUCTION

Since 1930, testosterone has been used to treat various gynecological problems such as uterine hemorrhage, myoma, dysmenorrhea, chronic mastitis, malignant endometrial tumors, and malignant breast tumors; the correlation between testosterone and the female libido was first reported by Loeser (in 1940) and was subsequently confirmed by Greenblatt et al. (in 1942) and Salmon et al. (in 1943) (1). However, the sexual response is multifactorial and depends on psychological and social aspects; on the effects of hormones such as estrogen, prolactin, progesterone, and oxytocin; and on the effects of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, including nitric oxide, dopamine, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (1-10). Therefore, it is difficult to determine the specific effects of testosterone on female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) (10).

In the last decade, increasing attention has been given to the neurobiology of sexual function due to the high prevalence of sexual difficulties in men and women as well as the successful use of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the treatment of erectile dysfunction (2).

Androgen levels and sexual behavior in aging women

A study conducted in the United States showed that 26.7% of all women of reproductive age and 54.2% of all postmenopausal women complain of decreased libido (11). In a study investigating the sexual life of the Brazilian population, 5.8% of the women in the 18-25 year age bracket reported inhibited sexual desire, as did 8.6% of those in the 41-50 year age bracket, 15.25% of those in the 51-60 year age bracket, and 19.9% of those over 60 years of age (12).

Dennerstein et al. (13) correlated sexual behavior and low androgen production in aging women, concluding that the decline in androgen production coincides with decreased sexual motivation and fantasies. In contrast, the results of a study of women in the 42-52 year age bracket varied by ethnicity, abdominal obesity, physical activity, mood, and smoking (14).

Studies investigating the correlation of appetite, sexual arousal, and orgasm with measurements of total testosterone, free testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate have yielded inconclusive results. In those studies, it was impossible to determine a cut-off point for androgen levels that would define and assist in the diagnosis of female androgen insufficiency (1,15,16). In contrast, the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation showed a correlation between increased complaints of HSDD and decreased free testosterone levels but not between decreased libido and total testosterone levels in aging women (17).

In aging individuals, sexual behavior does not depend solely on androgen levels. In addition to experiencing the end of ovarian function, menopausal women undergo physiological changes involving hormones and general health. Depression, relationship changes or partner loss, religious issues, and anxiety about the future are also important. All of these elements are interconnected, and social and emotional factors directly affect the somatic factors (18).

Fluctuations in estrogen levels in perimenopausal women can precipitate vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbances, and mastalgia, all of which impair the female sexual response (19). The decline in serum estrogen levels after menopause results in vaginal mucosal atrophy, vaginal muscle atrophy, and reduced vaginal acidity, which culminate in dyspareunia and can impair female sexual desire (20). Therefore, the fact that the prevalence of HSDD increases with age does not necessarily imply that the age-related changes occur as a direct result of decreased endogenous androgen levels.

Controversy regarding the diagnosis and treatment of androgen deficiency in women

The 2002 Princeton consensus statement on the definition, classification, and assessment of female androgen insufficiency (21) assessed the problems related to testosterone insufficiency in women and found that the current studies of those steroids are unsatisfactory, principally due to the lack of sensitivity or reliability in the determination of the normal levels. Therefore, the consensus statement recommended that equilibrium dialysis methods be developed for the adequate assessment of bioavailable testosterone in women and, in the absence of an ideal method, the free testosterone index be calculated for that purpose. Because increased sex hormone-binding globulin levels can also determine androgen insufficiency even in the presence of normal total testosterone levels, they should be considered for the calculation of bioavailable testosterone, and psychosocial causes should be evaluated. Finally, the consensus statement recommended that further studies be conducted, given that the physiological mechanisms regulating androgen homeostasis in women have yet to be clearly defined (21).

The 2006 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on Androgen Therapy (22) recommended against the use of androgen therapy in women. The recommendation was based on the lack of the following: well-defined criteria for the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency syndrome in women; normative data on the serum levels of total and free testosterone during the life cycle of women; data on the safety of long-term androgen administration; a correlation between sexual disorders and plasma testosterone levels; and accurate and reliable assays for determining circulating free and total testosterone. In addition, because clinical studies are limited and there are no long-term studies, the guidelines recommended that further studies be conducted and that the use of testosterone for the treatment of female HSDD be discouraged (22).

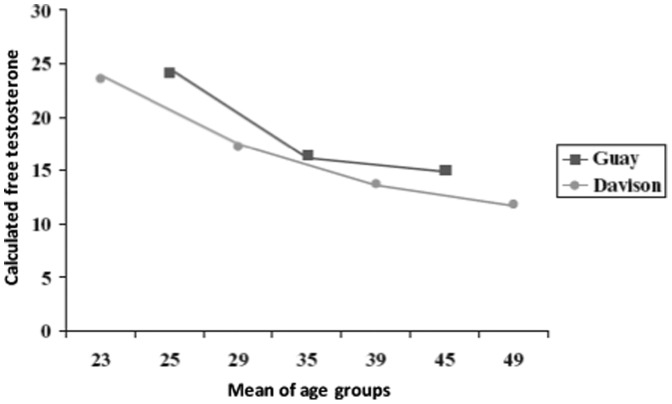

Traish et al. (23) disagreed with the 2006 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on Androgen Therapy (22) statement that there were no normative data on the serum levels of total and free testosterone during the life cycle of women, arguing that the panel ignored studies such as those by Davison et al. (24) and Guay et al. (25), which compared the levels of testosterone in healthy premenopausal women complaining of HSDD and defined the normal ranges for calculated free testosterone. In Figure 1, Traish et al. (23) show and compare the results obtained by Davison et al. (24) and Guay et al. (25). Traish et al. (23) also argued that although Davis et al. (15) found no correlation between total testosterone levels and sexual dysfunction, they found a correlation between low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels and female HSDD. Traish et al. (23) concluded that the lack of reliability of the results was solely due to the difficulty in accurately measuring free testosterone levels in women. The authors also refuted the argument that there was a lack of data on the safety of long-term testosterone administration in women (22), stating that various studies, such as those by Simon et al. (26), Buster et al. (27), Davis et al. (28), and Braunstein et al. (29), had shown only skin changes (oily skin, acne, and hirsutism) and that the beneficial effects of testosterone use (increased libido, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life) should be given greater weight. The aforementioned findings show that the use of testosterone for the treatment of female HSDD remains controversial.

Figure 1.

Free testosterone levels in young women from two separate and independent studies. The calculated free testosterone values are expressed in pmol/L. The mean age of the groups is shown in years (23). (Used with permission, Traish AM et al. Are the Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guidelines on Androgen Therapy in Women misguided? A commentary. J Sex Med. 2007;4(5):1223-34).

Mechanism of action of testosterone on the breasts and cardiovascular system

Testosterone administration in women raises concerns because of the effects of testosterone on breast tissue. The relationship between male steroids and breast cancer is complex because although epidemiological studies have shown an association between elevated androgen levels and the risk of breast tumors, experimental studies have shown conflicting results depending on the cell lineage, the dose and type of androgen, and the presence or absence of the estrogen receptor on the cell. In addition, in vivo studies involving rodents and rhesus monkeys suggest that androgens limit estrogen-induced mitogenic activity and cancer development in the breast (30).

Normal breast cell proliferation and breast tumor cell proliferation are regulated by the balance between the stimulating effects of estrogens and the inhibitory effects of androgens. However, the levels of androgen and estrogen required for these opposing mechanisms to occur have yet to be well established (31). In addition, because testosterone undergoes aromatization and is converted to estradiol, it can have opposing effects on breast tissue, meaning that it can either inhibit or stimulate breast cell proliferation (32).

Regarding the effects of testosterone on the cardiovascular system, testosterone receptors are distributed throughout the vasculature and are present on endothelial cells, smooth muscle, and myocardial fibers. Testosterone acts through three mechanisms. First, through a nongenomic pathway, testosterone stimulates the production of nitric oxide and inhibits the influx of calcium into the vascular endothelium, inducing vasodilation (33). Second, through a genomic pathway, testosterone acts through coregulatory proteins, which act on the androgen receptor, stimulating or restricting transcription; knowledge regarding this mechanism remains limited (33). Third, it also acts through the conversion of testosterone to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme (34). In addition, by binding to its receptor in ischemic conditions, testosterone can promote endothelial cell apoptosis, which consequently induces increased platelet adhesiveness, thrombus formation, and atherogenesis (35). Furthermore, primary atherosclerotic lesions are fatty streaks that consist of T lymphocytes and lipid-laden macrophages known as foam cells. Androgens increase foam cell formation and therefore favor ischemic processes (36).

METHODS

This was a review of studies published from 1988-2012. We searched the Medline (PubMed), Latin-American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Scientific Electronic Library Online, Excerpta Medica, and Cochrane Library databases using the search terms disfunção sexual feminina/female sexual dysfunction, desejo sexual hipoativo/female hypoactive sexual desire disorder, testosterona/testosterone, terapia androgênica em mulheres/androgen therapy in women, and sexualidade/sexuality as well as combinations thereof. We then selected articles written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish that included middle-aged human females or human females over 45 years of age. The selected articles included randomized controlled trials, literature reviews, and clinical trials.

A form was designed that contained the following items: 1) reviewer name; 2) article title; 3) author(s); 4) year of publication; 5) source; 6) keywords; and 7) abstract. The reviewers (i.e., the authors of the present study) independently read and evaluated the article titles and abstracts retrieved from the abovementioned databases to determine whether the articles were suitable for inclusion in the present review. Subsequently, the results were compared to determine the concordance between the reviewers, with discordant results being resolved by consensus. Duplicate studies were excluded.

A total of 3880 articles were retrieved initially. By reading the titles of the articles, we selected 531 potentially relevant studies. After reading the respective abstracts, we selected 274 articles, all of which were read in their entirety. After reading those articles in their entirety, we excluded 194. Of those, 99 were studies examining the use of therapies other than testosterone administration for the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women, 61 were studies examining the use of testosterone for purposes other than treating sexual dysfunction in women, and 34 were duplicate entries. A total of 80 articles remained and were classified by the type of study. From among those, seven of the reviewed articles showed results already described in our study and were excluded. We selected 20 randomized studies for this analysis (Table 1.

Table 1.

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials investigating the use of testosterone for the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women, retrieved from databases by the search terms (and Boolean operators) testosterone use OR androgen use in women AND sexual dysfunction, and published in 1988-2012.

| Author | Study participants | Study design | Duration; follow-up | Dose | Outcome |

| 1- Myers et al. (37) | Physiologically menopausal women (n = 40) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 10 weeks | Group 1: CEEs, 0.625 mg/dayGroup 2: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day + MPA, 5 mg/dayGroup 3: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day + MT, 5 mg/dayGroup 4: placebo | Increased pleasure from masturbationNo changes in mood, behavior, or sexual arousalNote: Sexual function was normal at the outset, and there was no ERT prior to the beginning of the study |

| 2- Davis et al. (38) | Physiologically menopausal women (n = 34) | Randomized, single-blind, trial | 3 months; 2 years | Group 1: T implants, 50 mg + estradiol implants, 50 mg | Increased sexual activity, sexual satisfaction, sexual pleasure, and orgasm |

| Group 2: Estradiol implants, 50 mg only | Increased bone mineral density | ||||

| Progesterone was administered to women who had not undergone hysterectomy | |||||

| 3- Shifren et al. (45) | Surgically menopausal women with sexual dysfunction (n = 75) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 12 weeks | Group 1: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day + transdermal T patch, 150 µg/day | Increased sexual activity, sexual pleasure, orgasm, sexual fantasy, and well-being in the group of women receiving daily doses of 300 µg of T |

| Group 2: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day orally + transdermal T patch, 300 µg/day | |||||

| Group 3: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day orally + placebo | |||||

| 4- Louie K.D. (46) | Surgically menopausal women in the 31-56 year age bracket (n = 75) | Randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 12 weeks | Group 1: Transdermal T patches, 150 µg/dayGroup 2: Transdermal T patches, 300 µg/dayGroup 3: placebo | The 300-µg/day dose was found to have significantly increased the frequency of sexual activity, sexual pleasure, and orgasm. However, it did not increase sexual desire, arousal, or receptivity |

| 5- Dobs et al. (47) | Physiologically menopausal women (n = 36) | Randomized, parallel, double-blind, trial | 16 weeks | Group 1: EEs, 1.25 mg/day (n = 18) | Increased sexual activity and pleasure in women receiving EEs (1.25 mg/day) + MT (2.5 mg/day) |

| Group 2: EEs, 1.25 mg/day + MT, 2.5 mg/day (n = 18) | Increased lean body mass, increased muscle strength, and reduced body fat in women receiving EEs (1.25 mg/day) + MT (2.5 mg/day) | ||||

| 6- Floter et al. (49) | Surgically postmenopausal women (n = 50) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 weeks | Group1: T undecanoate, 40 mg/day + estradiol valerate, 2 mg/dayGroup 2: Placebo + estradiol valerate, 2 mg/day | The use of estradiol valerate in combination with T undecanoate improved sexual response more significantly than did the use of estradiol valerate alone.The two groups were similar in terms of improved well-being and self-esteem. |

| 7- Goldstat et al. (39) | Premenopausal women with HSDD | Randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled trial | 12 weeks | Group1: T cream, 10 mg/dayGroup 2: Placebo | Improved sexual function, well-being, and mood |

| 8- Lobo et al. (48) | Postmenopausal women (n = 218) | Randomized, double-blind, trial | 16 weeks | Group 1: EEs, 0.625 mg/day (n = 111) | Improved libido and increased sexual frequency in women receiving EEs + MT |

| Group 2: EEs, 0.625 mg/day + MT, 1.25 mg/day (n = 107) | |||||

| 9- Buster et al. (27) | Surgically menopausal women (n = 533) | Multicenter randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 weeks | Group 1: daily ERT + transdermal T patches, 300 µg/day, applied twice weeklyGroup 2: daily ERT+ placebo, applied twice weekly | Significantly increased sexual desire and frequency of sexual activityImprovement in moodLow incidence of androgenic side effects on the skin |

| 10- Simon et al. (26) | Surgically menopausal women (n = 562) | Multicenter randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 weeks | Group 1: daily ERT + Transdermal T patches, 300 µg/day, applied twice weekly (n = 283)Group 2: daily ERT+ placebo, applied twice weekly (n = 279) | Slightly increased sexual desire and frequency of sexual activityImprovement in moodLow incidence of androgenic side effects on the skin |

| 11- Braunstein et al. (40) | Surgically menopausal women (n = 447) | Multicenter randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo controlled trial | 24 weeks | Group 1: daily ERT + Transdermal T patches, 150 µg/day, applied twice weekly (n = 107)Group 2: daily ERT + Transdermal T patches, 300 µg/day, applied twice weekly (n = 110)Group 3: daily ERT + Transdermal T patches 450 µg/day, applied twice weekly (n = 111)Group 4: daily ERT + placebo, applied twice weekly (n = 119) | At a dose of 300 µg, T was well tolerated and produced increases in libido and sexual frequencyIncreased androgenic (cutaneous) side effects in the women receiving T at a dose of 450 µg |

| 12- Davis et al. (28) | Women with HSDD submitted to oophorectomy and receiving transdermal estrogen (n = 77) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 weeks | The women receiving transdermal estrogen started to receive 300 µg/day of T (n = 37) or placebo (n = 40) | There was an increase in sexual desire, sexual arousal, and orgasm. |

| 13- Paula et al. (41) | Postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction (n = 85) | Randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 4 months | Group 1: HRT + placebo (4 months)Group 2: HRT + MT, 2.5 mg/day (4 months)Group 3: HRT + placebo (2 months), followed by HRT in combination with MT, 2.5 mg/day (2 months)Group 4: HRT + MT, 2.5 mg/day (2 months), followed by discontinuation of MT and initiation of HRT + placebo (2 months) | When receiving MT, the patients in groups 2, 3, and 4 showed improvement in sexual dysfunction, principally in sexual satisfaction and desire. However, in group 3, the results were similar in the two time periods.The use of HRT in combination with MT did not change hepatic enzyme levels or increase cardiovascular risk. |

| 14- Kingsberg et al. (42) | Surgically postmenopausal women with HSDD (n = 132) | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial | 6 months | Group 1: Transdermal T patches, 300 µg/day | There was an increase in sexual satisfaction and desire. |

| Group 2: placebo | |||||

| 15- El Hage et al. (43) | Postmenopausal women submitted to hysterectomy and receiving transdermal estrogen (n = 36) | Randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 3 months | Group 1:10 mg/day of topical T (AndroFeme® 1; Lawley Pharmaceuticals, Perth, Australia)Group 2: placebo | There was an increase in sexual desire, receptivity, and satisfaction.There was no improvement in energy or mood.There were no changes in the lipid profile. |

| 16- Penteado et al. (44) | Physiologically postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction (n = 60) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 6 months | Group 1: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day + MPA, 2.5 mg/day + placebo (n = 29)Group 2: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day + MPA, 2.5 mg/day + MT, 2.0 mg/day (n = 31) | The women who received MT experienced increased sexual desire in comparison with those who received placebo. However, there was no difference between the two groups in terms of the ability to achieve orgasm. |

| 17- Davis et al. (56) | Postmenopausal women with HSDD and a serum level of free T < 3.8 pmol/L (n = 261) | Randomized Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 16 weeks | Group 1: transdermal T spray, 56 µl/dayGroup 2: transdermal T spray, 90 µl/dayGroup 3: two 90 µl applications of transdermal T spray per dayGroup 4: placebo | At a dose of 90 µl/day, transdermal T spray increased libidoThe adverse effect most often reported was hypertrichosis, which correlated with the dose and site of application |

| 18- Blümel et al. (50) | Physiologically postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction (n = 40) | Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial with two parallel treatment arms | 3 months | Group1: CEEs, 0.625 mg/day+ micronized progesterone,100 mg/day + MT, 1.25 mg/day (n = 20)Group 2: placebo (n = 20) | The addition of MT to the therapeutic regimen improved the quality of life and sexuality of the postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction. |

| 19- Panay et al. (51) | Naturally postmenopausal women (n = 272) | Randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial | 6 months | Group 1: transdermal T patch, 300 µg/day | There was improvement of sexual dysfunction in the group of women receiving transdermal T. |

| Group 2: placebo | |||||

| 20- White et al. (52) | Naturally or surgically postmenopausal women with HSDD (n = 2,500, initially) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | The trial began in 2008, and the expected trial duration is 5 years. | Group 1: 0.22 g/day of 1% hydroalcoholic T gel (LibiGel; Biosante Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Lincolnshire, IL, USA)Group 2: placebo gel | The trial is still under way. |

CEEs: conjugated equine estrogens; DHT: dihydrotestosterone; EEs: esterified estrogens; ERT: estrogen replacement therapy; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HRT: hormone replacement therapy; HSDD: hypoactive sexual desire disorder; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; MPA: medroxyprogesterone acetate; MT: methyltestosterone; T: testosterone.

RESULTS

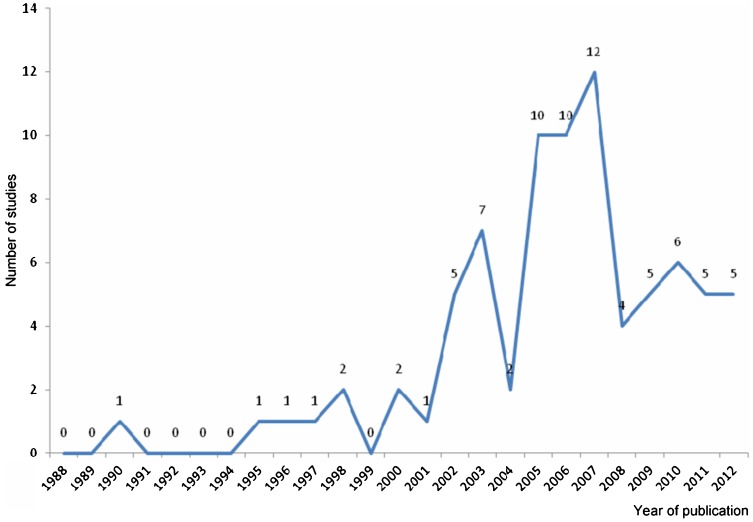

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the articles over the last 22 years, by year of publication. As seen in Figure 2, the number of studies began to increase in 2000, with peaks in 2003, 2005, and 2007.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the selected articles over the 1988-2012 period by year of publication.

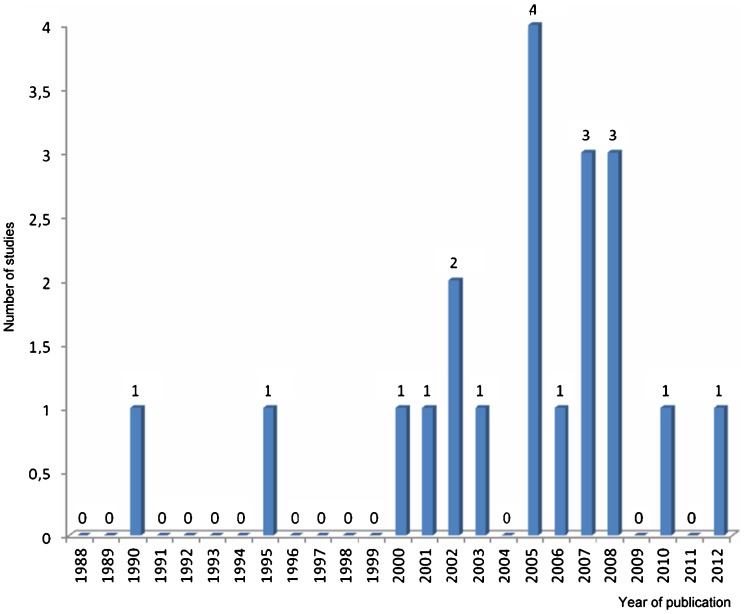

On the basis of the results of the 20 selected studies, we evaluated the effect of testosterone on the sexual response and identified the risks of testosterone administration. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the randomized, placebo-controlled trials by the year of publication. As shown in Figure 3, the number of randomized, placebo-controlled trials began to increase in 2000 and peaked in 2005, 2007, and 2008.

Figure 3.

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials investigating the use of testosterone and hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women and published in 1988-2012, distributed by year of publication.

DISCUSSION

Of the 20 randomized, placebo-controlled trials included in the present review, 2 (10%) were published in the 1988-1998 period and 18 (90%) were published in the 1999-2012 period, with peaks in 2005, 2007, and 2008 (Figure 3). Therefore, after 1998, with the advent of PDE5 inhibitors, there was a significant increase in the number of studies examining the use of testosterone for the treatment of HSDD in women.

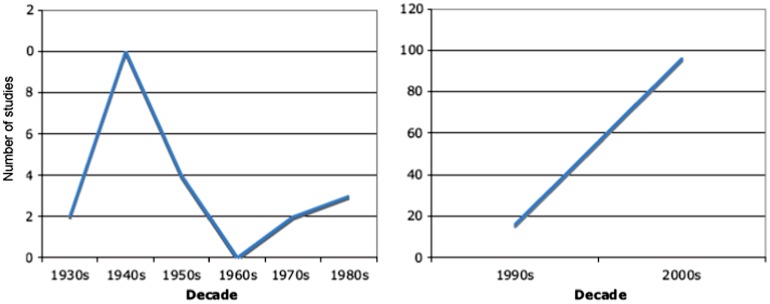

Traish et al. (1) reviewed the studies published in 1930-2000 that examined androgens, sexual function, and sexual dysfunction in women. The number of studies examining those issues peaked in the 1940s (when the effect of testosterone on the libido was first observed) but subsequently dropped and began increasing again in the 1990-2000 period. As shown in Figure 4, our findings corroborate those of Traish et al. (1).

Figure 4.

Number of studies examining androgens and sexual function or dysfunction in women and published in 1930-2000, distributed by decade and separated into two distinct periods (1). (Used with permission, Traish AM et al. Testosterone therapy in women with gynecological and sexual disorders: a triumph of clinical endocrinology from 1938 to 2008. J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):334-51).

On the basis of our analysis of 20 randomized, placebo-controlled trials, we can conclude that the male hormone has a positive effect on sexual response, having been reported to increase pleasure from masturbation (37), sexual desire (26-28),, the frequency of sexual activity (26,27,38,40),, sexual satisfaction (38,40-43,47),, and orgasm (28,38,45,46). One of the trials (52) began in 2008 and is still under way (with an expected trial duration of approximately 5 years). These findings are consistent with those of other studies showing increases in sexual desire, the frequency of sexual activity, and sexual satisfaction in women receiving androgen therapy (53-55).

Testosterone was found to have beneficial effects on libido regardless of the route of administration (oral administration, transdermal administration, or implants). However, in studies comparing two different doses of transdermal testosterone (i.e., 150 µg and 300 µg) in terms of their efficacy, testosterone was reported to have a beneficial effect on sexual response only when a 300-µg dose was used (40,45,46,56).

Of the 20 randomized, placebo-controlled trials included in the present review, 2 examined the risk that androgen administration poses to the cardiovascular system. El Hage et al. (43) and Paula et al. (41) reported that the use of testosterone increased the frequency of cardiac events.

Studies with the specific objective of evaluating the effect of testosterone on the cardiovascular system showed a risk of atherogenesis and thrombosis (35,36,57-59). In contrast, Lellano et al. (60) reported that testosterone provided cardiovascular protection, whereas other authors found neither an increased cardiovascular risk nor cardiovascular protection (61-63). Therefore, the effect of testosterone on the cardiovascular system remains inconclusive.

The impact of testosterone on the breasts is an important issue. The randomized trials shown in Table 1 do not allow us to draw conclusions because they were all short-term studies (the maximum duration being 24 weeks).

Of the 5 studies that analyzed the relationship between the administration of testosterone and the risk of breast cancer (64-68), only 1 showed a 2.5-fold increase in the risk of breast cancer (a relative risk of 2.48) among women receiving estrogen in combination with testosterone (65), whereas another showed that testosterone inhibited the cell proliferation induced by the estrogen-progestogen combination (64). The remaining 3 studies showed that the addition of testosterone did not induce the development of breast cancer (66-68). On the basis of these conflicting results, Kenemas et al. (69) stated that the long-term administration of testosterone for the treatment of HSDD in women merits further investigation.

One of the 20 randomized, placebo-controlled trials shown in Table 1 examined the risk of liver disease in women receiving androgens and showed no change in hepatic enzymes (41). In the literature, this has been reported only in cases in which the blood testosterone levels increased to supraphysiological levels (26,45,70).

Other adverse effects of the use of testosterone in women, such as hirsutism (55), deep voice, and an enlarged clitoris (71), should not be neglected. However, the most common adverse effects are acne and increased oiliness of the skin and hair (55), which were also reported in 3 of the studies shown in Table 1 (26,27,29). In addition, 10% of patients receiving 1.25 mg/day or 2.5 mg/day of methyltestosterone and 45% of those receiving 10 mg/day of the same were reported to have experienced these side effects (72,73).

Masculinization is rare and is due to the administration of high doses of androgens. Implants containing up to 300 µg/day of testosterone initially produce supraphysiological blood peaks, although these are transient and do not induce virilization (55).

Although the evidence shows that androgen administration positively affects the female sexual response, the impact that the long-term administration of androgens has on the physical health of women has yet to be clarified. No studies in the literature have evaluated the use of testosterone for the treatment of female HSDD or compared this treatment modality before and after the advent of the PDE5 inhibitors.

In the present review, we found that in the years preceding the commercial release of sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil, studies involving androgens were primarily conducted with the objective of treating myomas, perimenopausal symptoms, breast cancer, dysmenorrhea, and uterine hemorrhage and only showed that the male hormone had an effect on the female sexual response. As of 1998, the proportion of randomized studies investigating the effect of testosterone on female HSDD had increased from 10% to 90%, those studies having confirmed the positive effect of testosterone on libido. That increase was significant and suggests that the advent of PDE5 inhibitors motivated further studies aimed at resolving complaints of low libido in women with sexual dysfunction so that such women became sexually adjusted to their partners. We suggest that future research on other therapeutic approaches for sexual dysfunctions in women, investigating whether a correlation exists between the number of studies and the discovery of PDE5 inhibitors as well as the risks and benefits of such therapies, will be required.

Although there is no doubt about the positive effect of testosterone on the female sexual response, all the randomized trials examining this issue and published from 1998-2012 were short-term studies (the maximum duration being 24 weeks). Therefore, it is impossible to draw definitive conclusions regarding the side effects of the long-term administration of testosterone. However, it can be stated that during the study periods, testosterone administration was found to have no significant negative impact on the physical health of the treated women. In addition, the controversy regarding the diagnosis of female hypoandrogenism (this controversy existed before the advent of PDE5 inhibitors) remains unresolved. Therefore, although the number of studies has increased in recent years, there is still no consensus regarding the use of testosterone for the treatment of HSDD in women.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Traish AM, Feeley RJ, Guay AT. Testosterone therapy in women with gynecological and sexual disorders: a triumph of clinical endocrinology from 1938 to 2008. J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):334–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meston CM, Frohlich PF. The neurobiology of sexual function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1012–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldwell JD. A sexual arousability model involving steroid effects at the plasma membrane. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(1):13–30. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tillmann HC, Krüger UH, Manfred S. Prolactinergic and dopaminergic mechanisms underlying sexual arousal and orgasm in humans. World J Urolol. 2005;23:130–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musicki B, Liu T, Lagoda GA, Bivalacqua TJ, Strong TD, Burnett AL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulation in female genital tract structures. J Sex Med. 2009;Suppl 3:247–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato S, Braham CS, Putnam SK, Hull EM. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase and gonadal steroid interaction in the MPOA of male rats: co-localization and testosterone- induced restoration of copulation and nNOS immunoreactivity. Brain Res. 2005;1043(1-2):205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traish AM, Kim NN, Munarriz R, Moreland R, Goldstein I. Biochemical and physiological mechanisms of female genital sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(5):393–400. doi: 10.1023/a:1019831906508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowland DL. Neurobiology of sexual response in men and women. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(9):6–12. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900026705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halaris A. Neurochemical aspects of the sexual response cycle. CNS Spectr. 2003;8(3):211–6. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bancroft J. The endocrinology of sexual arousal. J Endocrinol. 2005;186(3):411–27. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West SL, D′Aloisio AA, Agans RP, Kalsbeek WD, Borisov NN, Thorp JM. Prevalence of Low Sexual Desire and Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in a Nationally Representative Sample of US Women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1441–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdo C. São Paulo: Summus; 2004. Descobrimento sexual do Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennerstein L, Koochaki PE, Barton I, Graziottin A. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in menopausal women: a survey of Western European women. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):212–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoro N, Torrens J, Crawford S, Allsworth JE, Finkelstein JS, Gold EB, Korenman S, et al. Correlates of circulating androgens in mid-life women: the study of women's health across the nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4836–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell RJ. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294(1):91–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwenkhagen A, Studd J. Role of testosterone in the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Maturitas. 2009;63(2):152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avis NE, Zhao X, Johannes CB, Ory M, Brockwell S, Greendale GA. Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2005;2(4):385–98. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000151656.92317.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwenkhagen A. Hormonal changes in menopause and implications on sexual health. J Sex Med. 2007;4(3):220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basson R. Clinical practice. Sexual desire and arousal disorders in women. N. Engl J Med. 2006;354(14):1497–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp050154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarrel PM. Sexuality and menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(4):26S–30S; discussion 31S-35S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, Burger H, Davis S, Dennerstein L, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(4):660–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02969-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wierman ME, Basson R, Davis SR, Khosla S, Miller KK, Rosner W, et al. Androgen Therapy in Women: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3697–710. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Traish A, Guay AT, Spark RF. Are the Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guidelines on Androgen Therapy in Women misguided. A commentary. J Sex Med. 2007;4(5):1223–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):3847–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guay A, Munarriz R, Jacobson J, Talakoub L, Traish A, Quirk F, et al. Serum androgen levels in healthy premenopausal women with and without sexual dysfunction: Part A. Serum androgen levels in women aged 20–49 years with no complaints of sexual dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(2):112–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon J, Braunstein G, Nachtigall L, Utian W, Katz M, Miller S, et al. Testosterone patch increases sexual activity and desire in surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5226–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buster JE, Kingsberg SA, Aguirre O, Brown C, Breaux JG, Buch A, et al. Testosterone patch for low sexual desire in surgically menopausal women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):944–52. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158103.27672.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis SR, van der Mooren MJ, van Lunsen RH, Lopes P, Ribot C, Rees M, et al. Efficacy and safety of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause. 2006;13(3):387–96. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000179049.08371.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braunstein GD. Management of Female Sexual Dysfunction in Postmenopausal Women by Testosterone Administration: Safety Issues and Controversies. J Sex Med. 2007;4:859–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotsopoulos J, Narod SA. Androgens and breast cancer. Steroids. 2012;77:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimitrakakis C. Androgens and breast cancer in men and women. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(3):533–47, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Schoultz B. Androgens and the breast. Maturitas. 2007;57(1):47–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: an overview. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(2):175–200. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee TK, Dinh H, Chaudhuri G, Nathan L. Testosterone attenuates expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 by conversion to estradiol by aromatase in endothelial cells: implications in atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(6):4055–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052703199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling S, Dai A, Williams MR, Myles K, Dilley RJ, Komesaroff PA, et al. Testosterone (T) enhances apoptosis-related damage in human vascular endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):1119–25. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCrohon JA, Death AK, Nakhla A, Jessup W, Handelsma DJ, Stanley KK, et al. Androgen receptor expression is greater in macrophages from male than from female donors. A sex difference with implications for atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;101(3):224–26. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers LS, Dixen J, Morrissette D, Carmichael M, Davidson JM. Effects of estrogen, androgen, and progestin on sexual psychophysiology and behavior in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70(4):1124–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-4-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis SR, McCloud P, Strauss BJ, Burger H. Testosterone enhances estradiol's effects on postmenopausal bone density and sexuality. Maturitas. 1995;21(3):227–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)00898-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, Wolfe R, Davis SR. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves wellbeing, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:390–8. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000060256.03945.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braunstein GD, Sundwall DA, Katz M, Shifren JL, Buster JE, Simon JA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: A randomized, placebo controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1582–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paula FJ, Soares JM, Jr, Haidar MA, Lima GR, Baracat EC. The benefits of androgens combined with hormone replacement therapy regarding to patients with postmenopausal sexual symptoms. Maturitas. 2007;56(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, Rodenberg C, Koochaki P, Derogatis L. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4(4 Pt 1):1001–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Hage G, Eden JA, Manga RZA. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the effect of testosterone cream on the sexual motivation of menopausal hysterectomized women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Climacteric. 2007;10(4):335–43. doi: 10.1080/13697130701364644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penteado SR, Fonseca AM, Bagnoli VR, Abdo CH, Júnior JM, Baracat EC. Effects of the addition of methyltestosterone to combined hormone therapy with estrogens and progestogens on sexual energy and on orgasm in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2008;11(1):17–25. doi: 10.1080/13697130701741932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(10):682–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009073431002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Louie KD. Transdermal testosterone replacement to improve women's sexual functioning. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:1571–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobs AS, Nguyen T, Pace C, Roberts CP. Differential effects of oral estrogen versus oral estrogen-androgen replacement therapy on body composition in postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87:1509–16. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, Block B, van der Hoop RG. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;(79):1341–52. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Floter A, Nathorst-Boos J, Carlstrom K, Schoultz B. Addition of testosterone to estrogen replacement in oophorectomized women: effects on sexuality and well-being, Climacteric. 2002;5(4):357–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blümel JE, Del Pino M, Aprikian D, Vallejo S, Sarrá S, Castelo-Branco C. Effect of androgens combined with hormone therapy on quality of life in post-menopausal women with sexual dysfunction. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2008;24(12):691–5. doi: 10.1080/09513590802454919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, Davis SR, Eden J, Lodhi I, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13(2):121–31. doi: 10.3109/13697131003675922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White WB, Grady D, Giudice LC, Berry SM, Zborowski J, Snabes MC. A cardiovascular safety study of LibiGel (testosterone gel) in postmenopausal women with elevated cardiovascular risk and hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Am Heart J. 2012;163(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarrel P, Dobay B, Wiita B. Estrogen and estrogen–androgen replacement in postmenopausal women dissatisfied with estrogen only therapy. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:847–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherwin BB. Randomized clinical trials of combined estrogen-androgen preparations: effects on sexual functioning. Fertil Steril. 2002;77 Suppl 4:S49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arlt W. Androgen Therapy in women. Euro J. Endocrinol. 2006;154(1):1–11. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis SR, Papalia MA, Norman RJ, O′Neill S, Redelman M, Williamson M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone metered-dose transdermal spray for treating decreased sexual satisfaction in premenopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(8):569–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-8-200804150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janssen I, Powell LH, Kazlauskaite R, Dugan SA. Testosterone and visceral fat in midlife women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) fat patterning study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(3):604–10. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Golden SH, Ding J, Szklo M, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Dobs A. Glucose and insulin components of the metabolic syndrome are associated with hyperandrogenism in postmenopausal women. The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):540–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman RP, Matthews KA, Chae C, Lasley BL, Brockwell S, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin and the free androgen index are related to cardiovascular risk factors in multiethnic premenopausal and perimenopausal women enrolled in the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN) Circulation. 2005;111(10):1242–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157697.54255.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lellamo F, Volterrani M, Caminiti G, Karam R, Massaro R, Fini M, et al. Testosterone therapy in women with chronic heart failure: a pilot double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(16):1310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leão LC, Durat MP, Silva DM, Bahia PR, Coeli CM, Farias MLF. Influence of methyltestosterone postmenopausal therapy on plasma lipids, inflammatory factors, glucose metabolism and visceral fat: a randomized study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154(1):131–9. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif MW, Bell R. Testosterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD004509. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004509.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Staa TP, Sprafka JM. Study of adverse outcomes in women using testosterone therapy. Maturitas. 2009;62(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hofling M, Hirschberg AL, Skoog L, Tani E, Hägerström T, von Schoultz B. Testosterone inhibits estrogen/progestogen-induced breast cell proliferation in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14(2):183–90. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000232033.92411.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Chen WY, Rosner B, Colditz G. A. Combined estrogen and testosterone use and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166 (14):1483–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ness RB, Albano JD, McTiernan A, Cauley JA. Influence of estrogen plus testosterone supplementation on breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(1):41–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jick SS, Hagberg KW, Kaye JA, Jick H. Postmenopausal estrogen-containing hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):74–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818fdde4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davis SR, Wolfe R, Farrugia H, Bell RJ. The incidence of invasive breast cancer among women prescribed testosterone for low libido. J Sex Med. 2009;6(7):1850–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kenemans P, van der Mooren MJ. Androgens and breast cancer risk. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(1):46–9. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.651925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Braunstein GD. Management of female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women by testosterone administration: Safety Issues and Controversies. J Sex Med. 2007;4:859–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis SR. Therapy The clinical use of androgens in female sexual disorders. J Sex Marital Ther. 1998;24(3):153–63. doi: 10.1080/00926239808404930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barrett-Connor E, Timmons C, Young R, Wiita B. Interim safety analysis of a two-year study comparing oral estrogen-androgen and conjugated estrogens in surgically menopausal women. J Womens Health. 1996;5:593–602. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lobo RA. Androgens in postmenopausal women: production, possible role, and replacement options. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56(6):361–76. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200106000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]