Abstract

The role of noise as an environmental pollutant and its impact on health are being increasingly recognized. Beyond its effects on the auditory system, noise causes annoyance and disturbs sleep, and it impairs cognitive performance. Furthermore, evidence from epidemiologic studies demonstrates that environmental noise is associated with an increased incidence of arterial hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Both observational and experimental studies indicate that in particular night-time noise can cause disruptions of sleep structure, vegetative arousals (e.g. increases of blood pressure and heart rate) and increases in stress hormone levels and oxidative stress, which in turn may result in endothelial dysfunction and arterial hypertension. This review focuses on the cardiovascular consequences of environmental noise exposure and stresses the importance of noise mitigation strategies for public health.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Noise, Pollutants, Sleep, Hypertension, Myocardial infarction, Stroke

Introduction

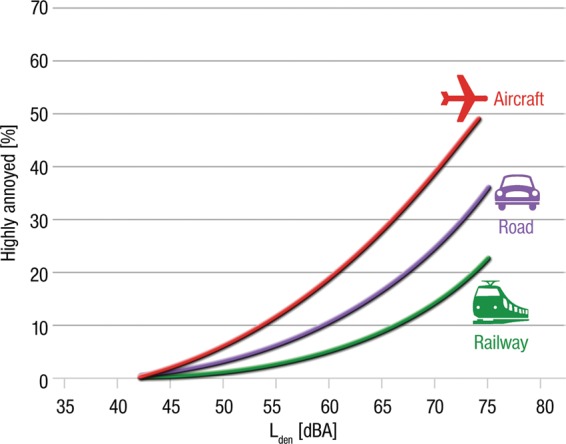

The Nobel Prize Winner Robert Koch predicted in 1910 that ‘One day man will have to fight noise as fiercely as cholera and pest’. Acutely, noise interferes with communication, disturbs sleep, and causes annoyance. At the same equivalent noise level, annoyance and self-reported sleep disturbance are usually highest for aircraft noise, and higher for road compared with rail traffic noise (Figure 1).1 Further, long-term exposure to relevant noise levels has been shown to be associated with negative health outcomes. Importantly, an impact on cardiovascular and autonomic homeostasis has been shown, even for noise levels that are quite commonly observed in urbanized regions: it is estimated that ∼40% of the population in European Union countries is exposed to road traffic noise at levels exceeding 55 dB of LDN (‘day–night level’, a measure of noise which summarizes average noise exposure >24 h, see Table 1) and that >30% is exposed to levels exceeding 55 dB at night (LNight, average noise level during the night-time hours, usually between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m.).2

Figure 1.

Percentage of persons highly annoyed by aircraft, road, and rail traffic noises. The curves were derived for adults on the basis of surveys (26 for aircraft noise, 19 for road noise, and 8 for railways noise) distributed over 11 countries. Adapted from Miedema and Oudcshoorn.1

Table 1.

Noise metrics and their definition

| SPL: The sound pressure level (SPL) is a logarithmic measure of the effective pressure of a sound relative to a reference value. It is measured in decibels (dB, see below) higher than a reference level. The reference sound pressure in air is 20 µPa (2×10−5 Pa), which is equivalent to the human hearing threshold at a sound frequency of 1000 Hz. |

| dB: A logarithmic scale to measure sound pressure levels. |

| LAeq: The energy-equivalent average A-weighted sound pressure level (LAeq) expressed in decibels is the most commonly used noise exposure metric reflecting (energetically) averaged noise exposure over a certain time period. The A-weighting (represented by the A in LAeq) accounts for the different sensitivity of the human ear at different sound frequencies. The duration of the averaging period within the 24 h day is often amended (e.g., LAeq16 h, usually reflecting the period from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m.). The LAeq is often calculated for long periods (e.g., over one year, the busiest 6 months of the year, etc.). |

| Lnight: LAeq for the night period (usually 11 p.m. and 7 a.m.) |

| LDN: Weighted LAeq over a 24 h period with a 10 dB penalty for nocturnal noise exposure (usually 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.) |

| LDEN: The 24 h LAeq with a 5 dB penalty for the evening (usually 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. or 7 p.m. to 11 p.m.) and a 10 dB penalty for the night (usually 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. or 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.). The penalties are introduced to indicate people's extra sensitivity to noise during the evening and the night. With respect to long-term health effects, these metrics are usually calculated as average annual exposure indicators. |

| Lmax: Maximum noise level in a given time period (during the passing of a train). Lmax is often better at predicting acute effects of single noise events than average noise levels. With respect to long-term health effects, however, equivalent sound levels seem more appropriate exposure metrics. |

The energy-equivalent average A-weighted SPL (LAeq) as expressed in decibels is the most commonly used indicator of the noise exposure that people perceive outside and inside their homes. The A-weighting accounts for the different sensitivity of the human ear at different sound frequencies.

The health burden of environmental noise has recently been quantified in a report of the World Health organization (WHO) in terms of disability-adjusted life years (i.e. the number of years lost because of disability or death, a measure that combines both morbidity and mortality). The WHO estimates that—in western Europeans—annually 45 000 years are lost due to noise-induced cognitive impairment in children, 903 000 due to noise-induced sleep disturbance, 61 000 due to noise-induced cardiovascular disease, and 22 000 due to tinnitus. Additionally, while not being a disease per se, noise-induced annoyance decreases quality of life and thus also causes disability, quantified in 587 000 disability-adjusted life years lost in the western European population.3

The present narrative review by subject matter experts is based on the current literature on the mechanisms and impact of noise on the cardiovascular system, will describe such non-auditory effects, with a particular focus on mechanisms and epidemiology of noise-induced arterial hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Physiological responses to acute noise

Noise exposure modifies the function of multiple organs and systems. Acute noise exposure, in both laboratory settings where traffic noise was simulated and in real-life environments, can cause increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, likely mediated by the release of stress hormones such as catecholamines (for review, see Babisch4,5). As shown by field studies, these acute effects occur not only at high sound levels in occupational settings but also at relatively low environmental noise levels when concentration, relaxation, or sleep is disturbed.6

The model describing the generalized psychophysiological reactions to stress formulated in 1977 by Henry and Stephens can be applied to noise.5,7,8 In this model, any form of stress (or any stimulus that is felt as such) provokes the activation of two different neuro-hormonal systems which ultimately help to cope with the stressor or at least to limit its damages. These reactions include the activation of sympathetic responses (fight–flight reactions) as well as the release of corticosteroids (defeat reaction). Particularly intense noise stimuli (for instance, when healthy volunteers are exposed to noise simulating a military low-altitude flight or a racing car), especially when their content appears aggressive or frightening, trigger the fight–flight reaction, with the secretion of adrenalin and noradrenaline from the adrenal medulla.9 The effects of this sympathetic arousal would help the organism to remove the stressor by actively confronting the problem or fleeing from it. Further, high-level noise events beyond the pain threshold and frightening sounds at lower levels also increase plasma cortisol levels,9 a so-called defeat reaction aimed at mitigating the damages expected from the stressor.

Notably, such changes do not require the involvement of cortical structures, i.e. the cognitive perception of noise does not appear to be necessary for its effects on cardiovascular homeostasis to become manifest. Indeed, the activation of fight–flight and defeat reactions is thought to involve subcortical regions of the brain like the hypothalamus, which has inputs to the autonomic nervous system, the endocrine system, and the limbic system.10,11 Such stress responses, in turn, result in changes in a number of physiological functions and in the homeostasis of several organs, including blood pressure, cardiac output, blood lipids (cholesterol, triglycerides, free fatty acids, phosphatides), carbohydrates (glucose), electrolytes (magnesium, calcium), thrombosis/fibrinolysis, and others.12

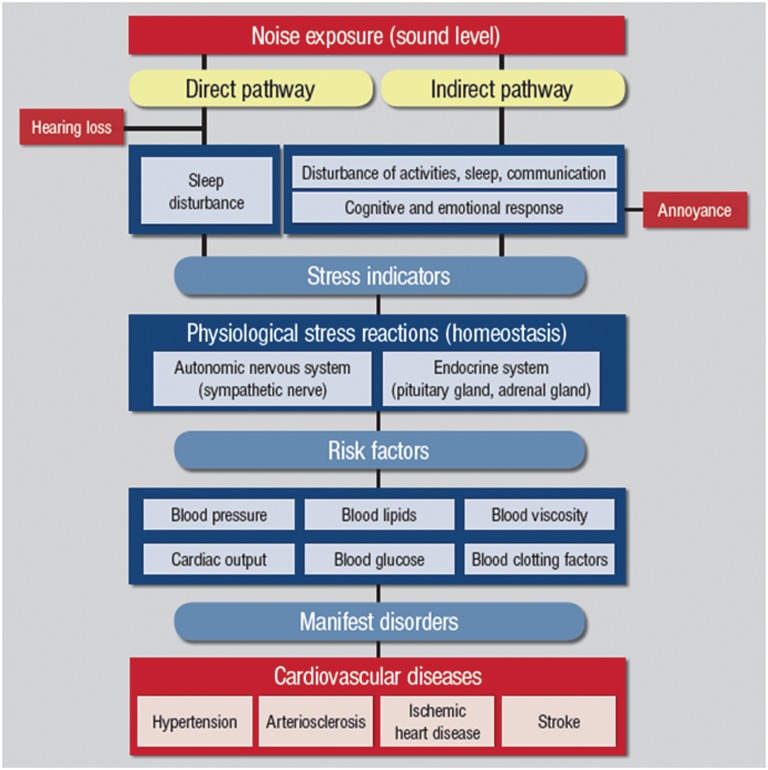

Experimental laboratory studies, observational field studies, and epidemiological studies all play important roles in elucidating the effects of environmental noise on cardiovascular health. Figure 2 shows a proposed reaction scheme for the effects of noise on the organism (from Sørensen et al. and Schmidt72,95). As described above, noise may exert its effects either directly, through synaptic interactions, or indirectly, through the emotional and the cognitive perception of sound. In other words, both the objective noise exposure (sound level) and its subjective perception determine the impact of noise on neuroendocrine homeostasis.

Figure 2.

Effects of nocturnal noise exposure on sleep and the cardiovascular system

Sleep is a complex and very active process, incorporating many vital physiological processes (e.g. protein biosynthesis, excretion of specific hormones, memory consolidation) that, in a broad sense, serve recuperation and preparation for the next wake period. Acute and chronic sleep restriction or fragmentation has been shown to be associated with inadequate pancreatic insulin secretion,13 decreased insulin sensitivity,14 changes in appetite regulating hormones,15 and increased sympathetic tone and venous endothelial dysfunction.16 At the same time, epidemiologic studies have shown that habitual short sleep (<6 h per night) is associated with obesity,17,18 diabetes,18,19 hypertension,20 cardiovascular disease,21 and all-cause mortality,22,23 stressing the importance of undisturbed sleep of sufficient length for health in general and cardiovascular health specifically. For these reasons, sleep disturbance is usually considered the most severe non-auditory effect of environmental noise exposure.24,25

The Ascending Reticular Activating System is part of the body's arousal system. It receives input from several sensory systems (including the auditory) and relays this information, for instance, to cardio-respiratory brainstem networks and through the Thalamus to the Cortex. Thus, we recognize, evaluate, and react to environmental sounds even while asleep.26 The Thalamus has a gating function, i.e. based on the sensory information and the current central nervous system state, information may be relayed to or withheld from the Cortex.27 If the information is passed on to the Cortex, it may lead to a Cortical arousal, that, if the subject is sleeping, may disturb or fragment sleep. Therefore, the organism's reaction to noise is not based on an all-or-nothing principle (i.e. not every noise event will lead to a conscious awakening). Rather, the reaction is fine-graded ranging from an isolated vegetative reaction (e.g. increase in heart rate and blood pressure) to a full cortical arousal with regaining of waking consciousness that usually includes body movements. Cortical arousals are regularly associated with vegetative arousals, and stronger cortical activations are associated with longer and more severe vegetative activations.28,29

Whether noise will induce an arousal and the degree of the arousal depends on the number of noise events and their acoustical characteristics,30 but also on situational moderators (like current sleep stage31) and noise susceptibility of the exposed subject.27 Repeated noise-induced arousals reduce sleep quality through changes in sleep structure that includes delayed sleep onset and early awakenings, fewer deep and rapid eye movement sleep, and more time spent awake and in superficial sleep stages.30,31 Although these effects are not specific for noise,32 and usually less severe compared with clinical sleep disorders like obstructive sleep apnoea,33 several laboratory and field studies unequivocally demonstrate that traffic noise causally disturbs sleep and, depending on noise levels, may impair performance, well-being and cardiovascular functions during the subsequent wake period.29,34–41

Exposure–response relationships have associated several traffic noise sources (e.g. road, rail, and aircraft noise) with awakenings, briefer cortical arousals, and vegetative arousals in both laboratory and field settings. These functions usually show monotonously increasing reaction probabilities with increasing maximum sound pressure levels (SPL). In fact, maximum SPLs as low as LAmax 33 dB have been shown to induce physiological reactions during sleep, i.e. once the organism is able to differentiate a noise event from the background, physiologic reactions can be expected (albeit with a low probability at low noise levels).35 At the same maximum SPL, aircraft noise has been shown to be less likely to induce both cortical and vegetative arousals compared with road and rail traffic noise, which was partly explained by the frequency distribution, duration, and SPL rise time of the noise events.30,36 Of note, subjective feelings of annoyance follow a different pattern, with a less pronounced effect of railroad noise, and a more pronounced effect of aircraft noise at the same equivalent noise level (Figure 1).1

Subjects exposed to noise usually habituate to the noise exposure. For example, the probability that noise causes physiologic reactions is in general higher during the first nights of a laboratory experiment compared with the last nights30 and exposure–response relationships derived in the field (where subjects have often been exposed to the noise for many years) are usually much shallower than those derived in laboratory settings, which often include exposure to unfamiliar noise events in an unfamiliar environment.35,42 Habituation is a reasonable mechanism that preserves energy resources. However, habituation is not complete, i.e. subjects continue to react to noise events even after several years of noise exposure. Unfortunately, little is known about individual differences in the ability to habituate to noise and potential predictors. Importantly, activations of the vegetative nervous system have been shown to habituate to a much lesser degree to noise compared with cortical arousals.30

Cardiovascular effects of nocturnal noise

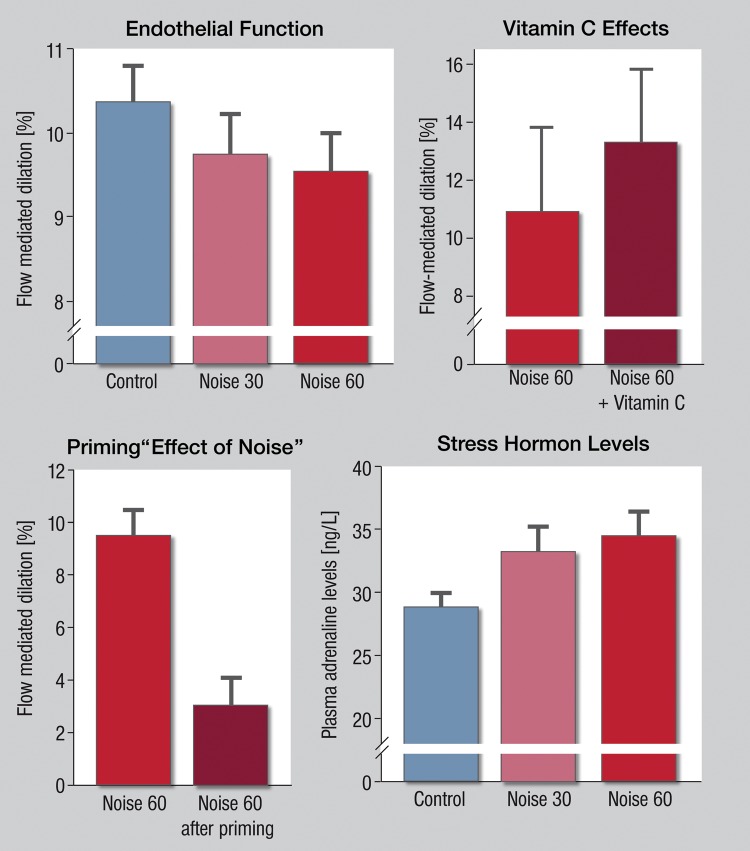

In a field study, nocturnal aircraft noise exposure played back with loudspeakers in the subjects’ bedrooms was shown to dose dependently affect parameters of vascular function (Figure 3), including endothelial function as measured by flow-dependent dilation of the brachial artery. Although this study was limited to single-night exposures to different levels of noise, a priming effect of noise was detected, i.e. the effect of noise was more pronounced if the subject had previously been exposed to noise. As expected, the changes in arterial function were paralleled by increased catecholamine production and impaired sleep quality, but morning plasma levels of cortisol and inflammatory markers IL-6 and C-reactive protein were unaffected by noise exposure.

Figure 3.

Effects of simulated aircraft noise (noise 30 and 60 reflecting 30 or 60 playback aircraft noise events) on endothelial function (as measured by flow-mediated dilation) and (lower right) stress hormone levels of healthy volunteers (adapted from Schmidt et al.95). The administration of the antioxidant vitamin C (upper right) was associated with improved endothelial function, demonstrating a role of oxidative stress.

These findings provide biologic plausibility for an association between nocturnal noise exposure and cardiovascular health. Increasingly, epidemiologic studies indicate that nocturnal noise exposure may be more relevant for cardiovascular health than day-time noise exposure (for a detailed discussion of epidemiologic studies and both day- and night-time noise exposure, see below). For aircraft noise, the HYENA study (‘Hypertension and Exposure to Noise near Airports’) found no significant association for day-time noise, but a significant increase in blood pressure with increases in night noise.43 Compatible with this evidence, it has been demonstrated that road traffic noise exposure has a larger impact in those who sleep with open windows or whose bedroom faces the road.44 A sustained decrease in blood pressure during the night (so-called dipping) seems to be important for resetting the cardiovascular system and for long-term cardiovascular health.45 Repeated nocturnal autonomic arousals may prevent blood pressure dipping and contribute to the risk for developing hypertension in those exposed to relevant levels of environmental noise for prolonged periods of time.46,47 In line with this, it was found that the risk to develop hypertension was higher in those sleeping with open windows during the night, but it was lower in those with sound insulation or where the bedroom was not facing the main road.48 A recent Swiss study showed an adverse effect of railway noise on blood pressure, that was more strongly associated with night-time exposure.49

The Night Noise Guidelines for Europe were published by the WHO in 2009 and constitute an expert consensus correlating four noise exposure ranges to negative health outcomes ranging from ‘no substantial biological effects’ to ‘increased risk of cardiovascular disease’.50 The WHO considers average nocturnal noise levels of LAeq,outside 55 dB as an interim goal when the recommended guideline value of 40 dB is not feasible in the short term for the prevention of noise-induced health effects.

In sum, nocturnal noise has been shown to affect both autonomic regulation (via increases in heart rate mediated by sympathetic activation and/or parasympathetic withdrawal51–53 and with increases in blood pressure54) and, directly, vascular function through the induction of endothelial dysfunction. Importantly, both endothelial dysfunction and reduced heart rate variability have been demonstrated to have prognostic value in patients with peripheral artery disease, arterial hypertension, and patients with an acute coronary syndrome or chronic stable coronary artery disease.55–57 Taken together, these observations provide a biological rationale for the increased incidence of arterial hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke in subjects with long-term exposure to relevant noise levels as described in the following paragraphs.

Epidemiological studies

Studies on chronic exposure to road traffic and/or railway or aircraft noise have reported a relationship with elevated blood pressure, hypertension or the use of antihypertensive medication, ischaemic heart disease including fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, dementia, and diabetes mellitus. Different study designs and methods for the assessment of the exposure, the disease, and potentially confounding factors were used. Based on these differences, the strength of the associations varies significantly across studies. Overall, however, studies demonstrate that environmental noise carries a health burden that has medical and economic implications: in the UK, day-time noise levels of ≥55 dB have been estimated to cause an additional 542 cases of hypertension-related myocardial infarction, 788 cases of stroke, and 1169 cases of dementia, with a cost valued at around £1.09 billion annually.58

Road traffic noise, blood pressure, and hypertension

A meta-analysis of 24 cross-sectional studies on the relationship between road traffic noise and the prevalence of hypertension reported an odds ratio (OR) of 1.07 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.02–1.12, P < 0.05) per 10 dB increase of the 16-h day-time average road traffic noise level (LAeq16h) in the range of <50 to >75 dB.59 A certain degree of heterogeneity among studies was detected with respect to age, gender, the way the exposure was assessed, the noise reference level used, and the duration of the exposure. For example, in the HYENA study, road traffic noise was linked to hypertension in men but not in women,43 and in the Groningen study and the PREVENT cohort road traffic noise was significantly associated with hypertension only in people aged 45–55 years.60 Similarly, a significant higher systolic blood pressure per 10 dB increase of the road traffic noise level was found in middle-aged subjects participating in a large Danish cohort study, with stronger and significant associations in men and older subjects.61 In this study, road traffic noise was not associated with diastolic blood pressure or self-reported hypertension. Co-morbidity was also found to be an effect modifier of the association between road traffic noise and blood pressure readings. For example, in the SAPALDIA 2 study, this association was only found in diabetics.62

Road traffic noise, coronary heart disease, and stroke

Road traffic noise was associated with myocardial infarction in case–control63–65 and cohort studies.66,67 The strength of this association increased when subjects with hearing impairment were excluded.

Of note, studies where no clear association was shown have also been published.44,69,70 A meta-analysis including four cohort and one case–control study on the relationship between road traffic noise and the incidence of hypertension reported an OR of 1.17 (CI = 0.87–1.57, P = n.s.) per 10 dB increase of the 16-h average road traffic noise level (LAeq16h) in the range of <60 to >75 dB.68 An updated meta-analysis of 12 studies (17 individual estimates, submitted for publication) reports an OR of 1.08 (95% CI = 1.04–1.13, P < 0.05) per 10 dB increase of the weighted day–night-noise level LDN within the range of 50–75 dB.71 While the older meta-analyses referred to noise levels from <60 to >75 dB, this more recent one refers to noise levels between <55 and >75 dB. Taken together, these data suggest that the exposure to sounds in the range between 55 and 60 dB, which would include large fractions of the population, may also contribute to the burden of disease.

Finally, exposure to residential road traffic noise was associated with a higher risk for stroke among people older than 64.5 years of age, showing a risk increase per 10 dB increase of the noise level (LDEN) (incidence rate ratio = 1.27, CI = 1.13–1.43, P < 0.0001).72 In sum, given the ubiquitous exposure, road traffic noise should be considered a relevant risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Railway noise

Railway noise has not been studied as much as noise from other transportation means in epidemiological studies. In the Danish cohort study mentioned above, a non-significantly higher risk was found in subjects that lived in areas where the cumulative noise level (railway + road) LDEN exceeded 60 dB.61 In the Swiss SALPADIA 2 study, railway noise, particularly during the night, was found to be significantly associated with systolic (0.84 mmHg, CI = 0.22–1.46 mmHg per 10 dB increase (LDEN), P < 0.01) and diastolic blood pressure (0.44 mmHg, CI = 0.06–0.81 mmHg; P < 0.05) readings of the study subjects.62 With respect to self-reported doctor's diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases, a borderline significant increase of risk was found in subjects exposed to railway noise levels (LDEN) of 50 dB and more (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.00–2.40; P < 0.10).73

Aircraft noise

Several studies within the last 10 years demonstrate a higher prevalence of annoyance, cardiovascular disease, or medication intake in persons exposed to aircraft noise.

Aircraft noise and arterial hypertension

In 2001, an increased prevalence of arterial hypertension in the vicinity of Stockholm airport was reported.74 Similarly, a dose–response relationship has been shown in the HYENA study with respect to night-time noise.43 A 14% increase in OR (CI = 1.01–1.29; P < 0.05) for arterial hypertension was in this study associated with every 10 dB increase in Lnight; in contrast, no effect was found for day-time aircraft noise exposure (LAeq: OR = 0.93, CI = 0.83–1.04; P = n.s.). Data from the European Union-funded RANCH (Road Traffic and Aircraft Noise Exposure and Children's Cognition and Health) study reported an association between both day-time and nocturnal noise exposure at home and blood pressure values in 9- to 10-year-old children living near Schiphol (Amsterdam) or Heathrow (London).75 A meta-analysis of four cross-sectional and one cohort study on the relationship between air traffic noise and the prevalence of hypertension reported an OR of 1.13 (CI = 1.00–1.28; P < 0.05) per 10 dB increase of the day–night weighted noise level (LDN) in the range of <55 to >65 dB.76

Studies carried out repeatedly in the area neighbouring Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport reported a higher prevalence of prescriptions for cardiovascular medications (OR ranging between 1.2 and 1.4 between high and low noise groups).77 Likewise, a cross-sectional study from the Cologne airport region in Germany demonstrated higher individual rates of cardiovascular medicine prescriptions in residents exposed to high aircraft noise levels, particularly during the night and the early morning hours (3–5 h).78 Higher risks were found for subjects for whom the average noise level during the late night period exceeded 40 dB. Results from the HYENA study also suggest an effect of aircraft noise on the use of antihypertensive medication, but this effect did not hold for all participating study centers.79 Results were more consistent across centres for the increased use of anxiolytics in relation to aircraft noise.79

Aircraft noise and coronary heart disease

The relationship between aircraft noise and coronary heart disease is less well investigated so far. Earlier studies carried out around Amsterdam's Schiphol airport gave some hints of a higher risk of cardiovascular disorders in subjects that lived closer to the airport.80,81 More recent studies, however, provided evidence of a higher cardiovascular risk for subjects who reside near airports. In an ecological study carried out around Heathrow airport, London, an increased risk of stroke and coronary heart disease was reported in relation to day- and night-time exposure to aircraft noise in people that were more exposed to aircraft noise than others.82 This exposure-dependent relationship was adjusted for aggregated data regarding ethnicity, social deprivation, incidence of lung cancer as a proxy for smoking, road traffic noise exposure, and air pollution. In another new census-block-based ecological study carried out ∼89 North American airports using hospital admission registry data, it was found that persons living in areas at the 90th percentile of noise exposure among census blocks within zip codes had a higher risk of hospitalization for ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. The results were adjusted for age, sex, and race as well as area level of socioeconomic status and ethnicity.83

A large cohort study in Switzerland reported an increased mortality due to myocardial infarction with increasing exposure levels and duration of aircraft noise, with a non-significant hazard ratio of 1.3 when persons exposed to noise levels (LDN)≥60 dB compared with those exposed to <45 dB after adjustment for several individual and geographical variables, including air pollution. As mentioned above, this hazard ratio increased to 1.5 (CI = 1.0–2.2; P < 0.10) and was significant when only residents exposed to noise for at least 15 years were included.84 In contrast, none of the other endpoints, including all-cause mortality, cerebrovascular disease, and stroke, was associated with aircraft noise. Furthermore, with increasing exposure to noise, the proportion of persons with tertiary education declined, whereas the proportion unemployed, the proportion of foreign nationals, and the proportion of people living in old and unrenovated buildings increased. Finally, in the cross-sectional HYENA study an association between (self-reported) heart disease or stroke (combined endpoint) and nocturnal aircraft noise was described.85 The association was particularly strong in subjects that had lived in the same place for ≥20 years. An OR of 1.25 (CI = 1.03–1.51; P < 0.05) per 10 dB increase of the night-noise level (LNight) was found.

Limitations of research in the area of environmental noise

A number of factors may modify the impact of noise on health. These include exposure-modifying factors such as the location of rooms and the quality of sound insulation, the habit to sleep with open or closed windows and length of residence and other behavioural risk factors. Most of the epidemiological studies controlled their results for a basic set of potentially confounding factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, smoking, body mass index, physical activity, alcohol intake, and/or ethnicity. Particularly, those studies where the subjects are actually seen provide a lot of additional information based on clinical interviews. However, response rates are sometimes low, which implies a possible selection bias. Ecological and other studies using health registries, on the other hand, do not suffer from the problem of low response rates, but individual data regarding personal risk factors are often missing. Since many behavioural risk factors that are related with worse health outcomes are correlated with socioeconomic status, they can partly be controlled. Aggregated indices of areal deprivation and socioeconomic status may serve as surrogates if individual data are not available. The fact that noise effects were seen when different methods and study types were applied supports the reasoning for an association. For example, cohort and case–control studies have a high analytic power, but observational cross-sectional studies may also provide information on relationships. Differences in study type (prospective, case–control, cross-sectional, ecologic) and the degree and quality of adjustment for confounding (i.e. residual confounding) may explain some of the discrepancies found between individual epidemiological studies. The fact that studies often only find noise associations with some but not all of their cardiovascular endpoints, and that not everybody will be affected (e.g. only men, only those within a certain age range) stresses the need to further investigate the exact mechanisms of how noise affects the cardiovascular system and why some are more susceptible than others. Of note, the question of ‘what comes first’ (temporality) may be easier to address with regards to noise epidemiology as compared with other associations between suspected risk factors and disease prevalence as it is unlikely that the decision to relocate to noisier areas might be determined by the presence of a disease.

There is evidence that ambient particle concentrations are also associated with the incidence of cardiovascular diseases.86 The potential confounding effect of air pollution was therefore considered in more recent studies, and, given the stronger association with air pollution, particularly in road traffic noise studies. Complicating these considerations, however, adjustment for air pollution indicators in multivariable statistical models is complex because modelled indicators of both exposures refer to the same input data (e.g. traffic volume and composition, traffic flow and speed, proximity to the road). It is an advantage of noise assessment that meteorology plays less of a role compared with air pollution within urban distances where houses are close to the streets. The fact that noise effects are also seen for noise sources other than road traffic (e.g. aircraft noise, railway noise, occupational noise that do not contribute as much to the air pollution exposure of the dwellings were the people live) supports the concept of an independent effect of noise. This is addressed in the present issue of the European Heart Journal.87 Using data from the German Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study, a population-based cohort study, the authors have demonstrated independent associations of long-term exposure to both fine particulate matter (PM) and road traffic noise with thoracic aortic calcification, a reliable measure of subclinical atherosclerosis.87 In this study, PM2.5 (PM with an aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) and Lnight (average level of nocturnal noise), but not LDEN, were associated with an increasing coronary calcification-burden, and the association remained valid after mutual adjustment. The authors concluded that long-term exposure to fine PM and night-time traffic noise are both independently associated with subclinical atherosclerosis and may both contribute to the association between road traffic and coronary artery disease. In a recent systematic review, it was concluded that confounding of cardiovascular effects by noise or air pollutants was low,88 even though this may have to do with the quality of the assessment methods of air pollutants.

Regarding effect modification, the studies showed a tendency towards stronger effects in middle-aged subjects and a tendency towards stronger effects in males. However, this was not consistent across studies. Furthermore, pre-existing co-morbidity was also found to be an effect modifying factor. Finally, a cumulative effect of noise from multiple sources of noise (e.g. work and traffic noise) has been shown.89,90

Conclusions

Taken together, the present review provides evidence that noise not only causes annoyance, sleep disturbance, or reductions in quality of life, but also contributes to a higher prevalence of the most important cardiovascular risk factor arterial hypertension and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases. The evidence supporting such contention is based on an established rationale supported by experimental laboratory and observational field studies, and a number of epidemiological studies. Meta-analyses have been carried out to derive exposure–response relationships that can be used for quantitative health impact assessments.91 Noise-induced sleep disturbance constitutes an important mechanism on the pathway from chronic noise exposure to the development of adverse health effects. The results call for more initiatives aimed at reducing environmental noise exposure levels to promote cardiovascular and public health. Recent studies indicate that people's attitude and awareness in particular towards aircraft noise has changed over the years.92,93 Noise mitigation policies have to consider the medical implications of environmental noise exposure. Noise mitigation strategies to improve public health include noise reduction at the source, active noise control (e.g. noise-optimized take-off and approach procedures), optimized traffic operations (including traffic curfews), better infrastructural planning, better sound insulation in situations where other options are not feasible, and adequate limit values.

Funding

M.B. was funded through NIH (grant R01 NR004281). T.G. and T.M. receive from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF01EO1003). T.G. also received from the Robert Müller Foundation, Foundation Heart of Mainz. The authors are responsible for the contents of this publication. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the University Medical Center of Mainz.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Miedema HME, Oudshoorn CGM. Annoyance from transportation noise: Relationships with exposure metrics DNL and DENL and their confidence intervals. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:409–416. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/environmental-health/noise . [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Regional office for Europe. Burden of disease from environmental noise – Quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. Copenhagen: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babisch W. Cardiovascular effects of noise. Noise Health. 2011;13:201–204. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.80148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babisch W. Stress hormones in the research on cardiovascular effects of noise. Noise Health. 2003;5:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basner M, Samel A, Isermann U. Aircraft noise effects on sleep: application of the results of a large polysomnographic field study. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:2772–2784. doi: 10.1121/1.2184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henry JP. Biological basis of the stress response. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1992;27:66–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02691093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ising H, Kruppa B. Health effects caused by noise: evidence in the literature from the past 25 years. Noise Health. 2004;6:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ising H, Braun C. Acute and chronic endocrine effects of noise: review of the research conducted at the Institute for Water, Soil and Air Hygiene. Noise Health. 2000;2:7–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spreng M. Possible health effects of noise induced cortisol increase. Noise Health. 2000;2:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spreng M. Central nervous system activation by noise. Noise Health. 2000;2:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundberg U. Coping with stress: neuroendocrine reactions and implications for health. Noise Health. 1999;1:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buxton OM, Cain SW, O'Connor SP, Porter JH, Duffy JF, Wang W, Czeisler CA, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003200. 129ra43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buxton OM, Pavlova M, Reid EW, Wang W, Simonson DC, Adler GK. Sleep restriction for 1 week reduces insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2010;59:2126–2133. doi: 10.2337/db09-0699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dettoni JL, Consolim-Colombo FM, Drager LF, Rubira MC, de Souza SB, Irigoyen MC, Mostarda CT, Borile S, Krieger EM, Moreno H, Jr, Lorenzi-Filho G. Cardiovascular effects of partial sleep deprivation in healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:232–236. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01604.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:643–653. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knutson KL, Van Cauter E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1129:287–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beihl DA, Liese AD, Haffner SM. Sleep duration as a risk factor for incident type 2 diabetes in a multiethnic cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Xi B, Liu M, Zhang Y, Fu M. Short sleep duration is associated with hypertension risk among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:1012–1018. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shankar A, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Lee HP, Yu MC. Sleep duration and coronary heart disease mortality among Chinese adults in Singapore: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1367–1373. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33:585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritschi L, Brown AL, Kim R, Schwela DH, Kephalopoulos S. Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise. Bonn, Germany: World Health Organization (WHO); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muzet A. Environmental noise, sleep and health. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald I, Taylor AM, Treisman M. Discriminative responses to stimulation during human sleep. Brain. 1960;83:440–453. doi: 10.1093/brain/83.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang-Vu TT, McKinney SM, Buxton OM, Solet JM, Ellenbogen JM. Spontaneous brain rhythms predict sleep stability in the face of noise. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R626–R627. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basner M, Griefahn B, Muller U, Plath G, Samel A. An ECG-based algorithm for the automatic identification of autonomic activations associated with cortical arousal. Sleep. 2007;30:1349–1361. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griefahn B, Brode P, Marks A, Basner M. Autonomic arousals related to traffic noise during sleep. Sleep. 2008;31:569–577. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basner M, Müller U, Elmenhorst E-M. Single and combined effects of air, road, and rail traffic noise on sleep and recuperation. Sleep. 2011;34:11–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basner M, Müller U, Griefahn B. Practical guidance for risk assessment of traffic noise effects on sleep. Appl Acoust. 2010;71:518–522. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brink M, Basner M, Schierz C, Spreng M, Scheuch K, Bauer G, Stahel W. Determining physiological reaction probabilities to noise events during sleep. Somnologie. 2009;13:236–243. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassel W, Ploch T, Griefahn B, Speicher T, Loh A, Penzel T, Koehler U, Canisius S. Disturbed sleep in obstructive sleep apnea expressed in a single index of sleep disturbance (SDI) Somnologie. 2008;12:158–164. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griefahn B, Marks A, Robens S. Noise emitted from road, rail and air traffic and their effects on sleep. J Sound Vib. 2006;295:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basner M, Isermann U, Samel A. Aircraft noise effects on sleep: application of the results of a large polysomnographic field study. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:2772–2784. doi: 10.1121/1.2184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marks A, Griefahn B, Basner M. Event-related awakenings caused by nocturnal transportation noise. Noise Contr Eng J. 2008;56:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horne JA, Pankhurst FL, Reyner LA, Hume K, Diamond ID. A field study of sleep disturbance: effects of aircraft noise and other factors on 5,742 nights of actimetrically monitored sleep in a large subject sample. Sleep. 1994;17:146–159. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohrstrom E, Hadzibajramovic E, Holmes M, Svensson H. Effects of road traffic noise on sleep: Studies on children and adults. J Env Psychol. 2006;26:116–126. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basner M, Glatz C, Griefahn B, Penzel T, Samel A. Aircraft noise: effects on macro- and micro-structure of sleep. Sleep Med. 2008;9:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basner M. Nocturnal aircraft noise increases objectively assessed daytime sleepiness. Somnologie. 2008;12:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elmenhorst EM, Elmenhorst D, Wenzel J, Quehl J, Mueller U, Maass H, Vejvoda M, Basner M. Effects of nocturnal aircraft noise on cognitive performance in the following morning: dose-response relationships in laboratory and field. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearsons K, Barber D, Tabachnick BG, Fidell S. Predicting noise-induced sleep disturbance. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarup L, Babisch W, Houthuijs D, Pershagen G, Katsouyanni K, Cadum E, Dudley ML, Savigny P, Seiffert I, Swart W, Breugelmans O, Bluhm G, Selander J, Haralabidis A, Dimakopoulou K, Sourtzi P, Velonakis M, Vigna-Taglianti F. Hypertension and exposure to noise near airports: the HYENA study. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:329–333. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Babisch W, Ising H, Gallacher JEJ, Sweetnam PM, Elwood PC. Traffic noise and cardiovascular risk: the caerphilly and speedwell studies, third phase-10-year follow up. Arch Environ Health. 1999;54:210–216. doi: 10.1080/00039899909602261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sayk F, Becker C, Teckentrup C, Fehm HL, Struck J, Wellhoener JP, Dodt C. To dip or not to dip: on the physiology of blood pressure decrease during nocturnal sleep in healthy humans. Hypertension. 2007;49:1070–1076. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haralabidis AS, Dimakopoulou K, Vigna-Taglianti F, Giampaolo M, Borgini A, Dudley ML, Pershagen G, Bluhm G, Houthuijs D, Babisch W, Velonakis M, Katsouyanni K, Jarup L, Consortium H. Acute effects of night-time noise exposure on blood pressure in populations living near airports. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:658–664. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrington MJ, Trinder J. Blood pressure and heart rate during continuous experimental sleep fragmentation in healthy adults. Sleep. 2008;31:1701–1712. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.12.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lercher P, Widmann U, Kofler W. InterNoise. Nice, France: 2000. Transportation noise and blood pressure: the importance of modifying factors. Abstract 4. Société Française d'Acoustique. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dratva J, Phuleria HC, Foraster M, Gaspoz J-M, Keidel D, Künzli N, Liu LJS, Pons M, Zemp E, Gerbase MW, Schindler C. Transportation noise and blood pressure in a population-based sample of adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;120:50–55. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organisation. Night Noise Guidelines for Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haralabidis AS, Dimakopoulou K, Vigna-Taglianti F, Giampaolo M, Borgini A, Dudley ML, Pershagen G, Bluhm G, Houthuijs D, Babisch W, Velonakis M, Katsouyanni K, Jarup L. Acute effects of night-time noise exposure on blood pressure in populations living near airports. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:658–664. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lusk SL, Gillespie B, Hagerty BM, Ziemba RA. Acute effects of noise on blood pressure and heart rate. Arch Environ Health. 2004;59:392–399. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.59.8.392-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bjor B, Burstrom L, Karlsson M, Nilsson T, Naslund U, Wiklund U. Acute effects on heart rate variability when exposed to hand transmitted vibration and noise. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang TY, Lai YA, Hsieh HH, Lai JS, Liu CS. Effects of environmental noise exposure on ambulatory blood pressure in young adults. Environ Res. 2009;109:900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munzel T, Sinning C, Post F, Warnholtz A, Schulz E. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and prognostic implications of endothelial dysfunction. Ann Med. 2008;40:180–196. doi: 10.1080/07853890701854702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muxel S, Fasola F, Radmacher MC, Jabs A, Munzel T, Gori T. Endothelial functions: translating theory into clinical application. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;45:109–115. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buccelletti E, Gilardi E, Scaini E, Galiuto L, Persiani R, Biondi A, Basile F, Silveri NG. Heart rate variability and myocardial infarction: systematic literature review and metanalysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harding AH, Frost GA, Tan E, Tsuchiya A, Mason HM. The cost of hypertension-related ill-health attributable to environmental noise. Noise Health. 2013;15:8. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.121253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Kempen E, Babisch W. The quantitative relationship between road traffic noise and hypertension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1075–1086. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328352ac54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Kluizenaar Y, Gansevoort RT, Miedema HM, de Jong PE. Hypertension and road traffic noise exposure. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:484–492. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318058a9ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sørensen M, Hvidberg M, Hoffmann B, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Lillelund KG, Jakobsen J, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Exposure to road traffic and railway noise and associations with blood pressure and self-reported hypertension: a cohort study. Environ Health. 2011;10:92. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dratva J, Phuleria HC, Foraster M, Gaspoz JM, Keidel D, Kunzli N, Liu LJ, Pons M, Zemp E, Gerbase MW, Schindler C. Transportation noise and blood pressure in a population-based sample of adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:50–55. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Babisch W, Beule B, Schust M, Kersten N, Ising H. Traffic noise and risk of myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2005;16:33–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147104.84424.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Selander J, Nilsson ME, Bluhm G, Rosenlund M, Lindqvist M, Nise G, Pershagen G. Long-term exposure to road traffic noise and myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2009;20:272–279. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819463bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Babisch W, Ising H, Kruppa B, Wiens D. The incidence of myocardial infarction and its relation to road traffic noise – the Berlin case-control studies. Environ Int. 1994;20:469–474. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gan WQ, Davies HW, Koehoorn M, Brauer M. Association of long-term exposure to community noise and traffic-related air pollution with coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:898–906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sørensen M, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Jensen SS, Lillelund KG, Beelen R, Schmidt EB, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Road traffic noise and incident myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babisch W. Road traffic noise and cardiovascular risk. Noise Health. 2008;10:27–33. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.39005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beelen R, Hoek G, Houthuijs D, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, Fischer P, Schouten LJ, Armstrong B, Brunekreef B. The joint association of air pollution and noise from road traffic with cardiovascular mortality in a cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:243–250. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.042358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Kluizenaar Y, van Lenthe FJ, Visschedijk AJH, Zandveld PYJ, Miedema HME, Mackenbach JP. Road traffic noise, air pollution components and cardiovascular events. Noise Health. 2013;15:328–337. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.121230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babisch W. Updated exposure-response relationship between road traffic noise and coronary heart disease. Noise Health. 2014 doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.127847. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sørensen M, Hvidberg M, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Lillelund KG, Jakobsen J, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Road traffic noise and stroke: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:737–744. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eriksson C, Nilsson ME, Willers SM, Gidhagen L, Bellander T, Pershagen G. Traffic noise and cardiovascular health in Sweden: the roadside study. Noise Health. 2012;14:140–147. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.99864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenlund M, Berglind N, Pershagen G, Jarup L, Bluhm G. Increased prevalence of hypertension in a population exposed to aircraft noise. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:769–773. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.12.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Kempen E, van Kamp I, Fischer P, Davies H, Houthuijs D, Stellato R, Clark C, Stansfeld S. Noise exposure and children's blood pressure and heart rate: the RANCH project. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:632–639. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Babisch W, Kamp I. Exposure-response relationship of the association between aircraft noise and the risk of hypertension. Noise Health. 2009;11:161–168. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.53363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knipschild P, Oudshoorn N. VII. Medical effects of aircraft noise: drug survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1977;40:197–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01842083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Greiser E, Greiser C, Janhsen K. Night-time aircraft noise increases the prescription for anthypertensive and cardiovascular drugs irrespective of social class – the Cologne-Bonn Airport study. J. Public Health. 2007;15:327–337. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Floud S, Vigna-Taglianti F, Hansell A, Blangiardo M, Houthuijs D, Breugelmans O, Cadum E, Babisch W, Selander J, Pershagen G, Antoniotti MC, Pisani S, Dimakopoulou K, Haralabidis AS, Velonakis V, Jarup L. Medication use in relation to noise from aircraft and road traffic in six European countries: results of the HYENA study. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:518–524. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.058586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knipschild P. VI. Medical effects of aircraft noise: general practice survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1977;40:191–196. doi: 10.1007/BF01842082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knipschild PV. Medical effects of aircraft noise: community cardiovascular survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1977;40:185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01842081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hansell AL, Blangiardo M, Fortunato L, Floud S, de Hoogh K, Fecht D. Aircraft noise and cardiovascular disease near Heathrow airport in London: small area study. Br Med J. 2013;347:f5432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Correia A, Peters JL, Levy JI, Melly S, Dominici F. Residential exposure to aircraft noise and hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases: multi-airport retrospective study. Br Med J. 2013;347:f5561. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huss A, Spoerri A, Egger M, Roosli M. Aircraft noise, air pollution, and mortality from myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2011;21:829–836. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f4e634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Floud S, Blangiardo M, Clark C, de Hoogh K, Babisch W, Houthuijs D, Swart W, Pershagen G, Katsouyanni K, Velonakis M, Vigna-Taglianti F, Cadum E, Hansell AL. Exposure to aircraft and road traffic noise and associations with heart disease and stroke in six European countries: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2013;12:89. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC, Jr, Tager I Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kälsch H, Henning F, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, Dragano N, Jakobs H, Memmesheimer M, Erbel R, Jöckel KH, Hoffmann B on behalf of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigative Group. Are air pollution and traffic noise independently associated with atherosclerosis – the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Eur Heart J. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht426. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tetreault LF, Perron S, Smargiassi A. Cardiovascular health, traffic-related air pollution and noise: are associations mutually confounded? A systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:649–666. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Selander J, Bluhm G, Nilsson M, Hallqvist J, Theorell T, Willix P, Pershagen G. Joint effects of job strain and road-traffic and occupational noise on myocardial infarction. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39:195–203. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Babisch W, Ising H, Gallacher JEJ, Elwood PC, Sweetnam PM, Yarnell JWG, Bainton D, Baker IA. Traffic noise, work noise and cardiovascular risk factors: the Caerphilly and Speedwell Collaborative Heart Disease Studies. Environ Int. 1990;16:425–435. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Basner M, Babisch W, Davis A, Brink M, Clark C, Janssen S, Stansfeld S. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X. doi:10.1016/S0140–6736(13)61613-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Babisch W, Houthuijs D, Pershagen G, Cadum E, Katsouyanni K, Velonakis M, Dudley ML, Marohn HD, Swart W, Breugelmans O, Bluhm G, Selander J, Vigna-Taglianti F, Pisani S, Haralabidis A, Dimakopoulou K, Zachos I, Jarup L. Annoyance due to aircraft noise has increased over the years – results of the HYENA study. Environ Int. 2009;35:1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.European Environment Agency. Good practice guide on noise exposure and potential health effects. 2010. EEA Technical report No 11/2010 http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/good-practice-guide-on-noise .

- 94.Babisch W. The noise/stress concept, risk assessment and research needs. Noise Health. 2002;4:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmidt FP, Basner M, Kroger G, Weck S, Schnorbus B, Muttray A, Sariyar M, Binder H, Gori T, Warnholtz A, Munzel T. Effect of nighttime aircraft noise exposure on endothelial function and stress hormone release in healthy adults. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3508a–3514a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.