Abstract

Oral chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a serious complication of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Scales and instruments to measure oral cGVHD activity and severity have not been prospectively validated. The objective of this study was to describe the characteristics of oral cGVHD and determine the measures most sensitive to change. Patients enrolled in the cGVHD Consortium with oral involvement were included. Clinicians scored oral changes according to the NIH criteria, and patients completed symptom and quality of life measures at each visit. Both rated change on an 8-point scale. Of 458 participants, 72% (n=331) had objective oral involvement at enrollment. Lichenoid change was the most common feature (n=293; 89%). At visits where oral change could be assessed, 50% of clinicians and 56% of patients reported improvement, with worsening reported in 4–5% for both groups (weighted kappa = 0.41). Multivariable regression modeling suggested that the measurement changes most predictive of perceived change by clinicians and patients were erythema and lichenoid, NIH severity and symptom scores. Oral cGVHD is common and associated with a range of signs and symptoms. Measurement of erythema and lichenoid changes and symptoms may adequately capture the activity of oral cGVHD in clinical trials but require prospective validation.

Keywords: oral cavity, stem cell transplantation, graft-versus-host disease, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a frequent complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality1. The oral cavity, including the oral mucosa and salivary glands, is one of the most frequently affected anatomic sites, with upwards of 80% of all patients with cGVHD demonstrating involvement2, 3. The consequences of oral cGVHD can be highly significant, with mucosal lichenoid changes leading to pain and limited oral intake, and salivary gland changes contributing to oral discomfort, difficulty chewing and swallowing, and an increased rate of oral infections4, 5. The oral cavity may require extended intensive localized ancillary therapy (e.g. topical corticosteroids) even when other sites of cGVHD are well-controlled with systemic immunosuppressive agents or no longer active, and long-term follow-up is essential due to an increased risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma6.

In 2005, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease established several standardized instruments for assessing oral disease activity. These included (a) the Oral cGVHD Activity Assessment instrument for measuring objective response to therapy over time, (b) the Oral cGVHD Staging Score, which assesses the impact of oral cGVHD on function, and (c) the Chronic GVHD Activity Assessment – Patient Self Report, which assesses patient symptoms of pain, sensitivity, and dryness7–9. The intent of these instruments was in large part to establish standardized criteria to facilitate multicenter research collaborations, and to better allow meaningful comparisons to be made across studies. Despite several years of clinical use, these instruments have not yet been prospectively validated in a formal manner, and it remains unclear the extent to which they may be effective in measuring clinical changes.

It was within this context that the Chronic GVHD Consortium initiated a multicenter, prospective, longitudinal study that was designed to both validate and refine the recommendations of the NIH Consensus Conference, and to ultimately provide improved/simplified clinical tools10. Patients enrolled in this observational study have been followed every six months with comprehensive systematic clinical evaluations including detailed oral cavity assessments. The objective of this study was to summarize the oral cavity data collected from the Consortium cohort, and to determine which oral cGVHD measurement scales are best correlated with perceived symptom changes, with the goal of eliminating insensitive or duplicative measurements so as to simplify the assessment approach for clinical trials.

METHODS

Subjects

Patients with cGVHD that were enrolled in a prospective multicenter observational cohort study (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00637689) from August, 2007 to December, 2010 were included in this analysis. Patients were eligible if greater than two years of age and diagnosed with cGVHD requiring systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Patients were classified as either incident (within three months of cGVHD diagnosis) or prevalent (more than three months after diagnosis but no more than three years after transplantation) cases. Comprehensive clinician- and patient-based symptomatic and clinical evaluations, including the National Institutes of Health criteria were completed every six months as described by The Chronic GVHD Consortium 10. Incident cases had an additional assessment three months after enrollment. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each of the nine study sites (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Medical College of Wisconsin, Moffitt Cancer Center, Northwestern Children’s Hospital, Stanford University, University of Minnesota, Vanderbilt University, Washington University Medical Center), and all subjects provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Oral Activity Measures

Both clinician- and patient-assessed instruments were used to collect symptomatic and clinical data on the severity and impact of oral cavity cGVHD changes (Supplemental file). The clinician-assessed instruments included the NIH severity score (0–3), the NIH oral mucosal score (erythema, lichenoid changes, ulcerations and mucoceles; composite and individual scores), mouth pain score (0–3) and the Johns Hopkins mouth pain score (0–3)11. Additional clinician-assessed measures that were considered in this analysis included the esophagus score (assesses dysphagia/odynophagia, 0–3), NIH overall cGVHD severity score (0–3), and patient weight (kg).

The patient-based assessments included the NIH oral symptom scores (pain, sensitivity, dryness; 0–10)9, Lee mouth symptom score (two 0–4 items, scored 0–100)12, and Lee nutrition score (five 0–4 items, scored 0–100)12. In addition, clinicians and patients independently scored their overall perception of change in the oral cavity on an eight point scale ranging from “resolved” (“completely gone” for patients) to “very much worse”10.

Ancillary therapies prescribed specifically for the management of oral cGVHD were not collected.

Statistical Methods

Clinician-reported oral cGVHD involvement was defined as any mouth abnormality scored on one of the six primary clinician measures (severity, 4 oral mucosal scores, pain). Patient-reported mouth involvement was defined as any symptoms noted on the pain, sensitivity or Lee mouth symptom score. (Patient report of dryness without other symptoms was not defined as oral cGVHD involvement.) Patient socio-demographics and transplantation characteristics were compared by oral involvement vs. no oral involvement at cohort enrollment. Descriptive statistics were presented as median and range for continuous variables, and as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons between two groups were made with the two-sample t-test for continuous variables, and chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Changes in scores for validated measurement scales were calculated by subtracting the values recorded at sequential visits. In order to limit the analysis to patients with clinically significant oral cGVHD, only paired visits with oral involvement reported by both clinician and patient at the previous or current visit were included in the longitudinal analysis of change. Agreement between clinician and patient-reported oral symptom changes was tested by the Fleiss-Cohen weighted kappa statistic for ordinal measures. The 8-level perceived symptom change scales were each collapsed into three categories: Improvement (“(1) resolved/completely gone”, “(2) very much better”, “(3) moderately better”), Stable (“(4) a little better”, “(5) about the same”, “(6) a little worse”), or Worsening (“(7) moderately worse”, “(8) very much worse”). Established interpretation was used for the kappa coefficient (0, no agreement; 0–0.2, slight agreement; 0.2–0.4 fair agreement; 0.4–0.6, moderate agreement; 0.6–0.8, substantial agreement; 0.8–1.0, almost perfect agreement13).

Linear regression models examined correlations of change scores of measurement scales with perceived changes reported by clinicians or patients. Multivariable models were fitted in order to determine whether measurement scales added predictive value beyond information from patient and disease characteristics. Candidate clinical variables included patient age at transplant, sex, race, education, mental quality of life, diagnosis, disease stage, donor-patient gender matching and CMV serostatus, donor type, conditioning intensity, stem cell source, Karnofsky Performance Status and/or platelet count at chronic GVHD onset, prior acute GVHD, study site, and incident vs. prevalent case at enrollment. Linear mixed models with random patient effects were used to account for within-patient correlations14, 15. Type I error was controlled by considering a p value of 0.01 or lower as statistically significant. Selected statistical interactions were evaluated between oral cGVHD measures and clinical variables, and among oral cGVHD measures.

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS/STAT software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 2.9.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 458 patients with cGVHD were enrolled in the prospective observational study through the end of 2010 and included in the analysis, accounting for 1,419 study visits including 961 follow-up visits (Table 1). Patients completed a median of three study visits (range 1–8). The rate of missing data for clinician-reported oral measures was <1% for each measure, and the rate for patient-reported oral measures ranged from 16–17%. Missing data were not imputed; the primary analysis method (linear mixed models) generally accommodates data missing at random16. Patients were enrolled at a median of 12.2 months post-transplantation and were followed for a median of 16.5 months (range 0.3 – 47.1) from the time of enrollment to the last visit date. Patients were transplanted for a range of hematologic malignancies and bone marrow failure conditions, with the most frequent being AML, MDS, NHL, and ALL, with just over half (57%) receiving myeloablative conditioning and the overwhelming majority (88%) receiving peripheral blood stem cell grafts. The majority of cases (55%) were incident and 97% were adults aged 18 or older (14 pediatric patients), with a median age of 51 (range 2–79) at the time of study registration. Chronic GVHD was preceded by acute GVHD in 68%, with no difference in those with or without oral involvement.

Table 1.

Patient demographics of the total study cohort and those with and without oral cGVHD involvement at enrollment.

| Oral cGVHD | No Oral cGVHD | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 239* | 154* | |

| Median age (range) | 50 (2–79) | 53 (8–73) | 0.37 |

| Sex | |||

| female (%) | 105 (44) | 63 (41) | 0.55 |

| male (%) | 134 (56) | 91 (59) | |

| Study site | |||

| FHCRC | 134 (56) | 39 (25) | <0.001 |

| Other | 105 (44) | 115 (75) | |

| Case type | |||

| incident | 131 (55) | 83 (54) | 0.86 |

| prevalent | 108 (45) | 71 (46) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| AML/ALL | 110 (46) | 69 (45) | 0.03 |

| CML/CLL | 22 (9) | 28 (18) | |

| MDS | 44 (19) | 18 (12) | |

| NHL/HD | 39 (16) | 29 (19) | |

| Other | 24 (10) | 10 (6) | |

| Stem cell source | |||

| bone marrow | 16 (7) | 10 (6) | 0.01 |

| peripheral blood | 217 (90) | 130 (85) | |

| cord blood | 6 (3) | 14 (9) | |

| Conditioning intensity** | |||

| myeloablative | 135 (56) | 88 (58) | 0.84 |

| non-myeloablative | 104 (44) | 65 (42) | |

| Donor matching** | |||

| matched related | 113 (47) | 65 (42) | 0.60 |

| matched unrelated | 89 (37) | 60 (39) | |

| mismatched | 37 (15) | 28 (18) | |

| Acute GVHD | |||

| yes | 161 (67) | 103 (67) | 0.92 |

| no | 78 (33) | 51 (33) | |

| Global NIH cGVHD severity | 0.26 | ||

| Mild or less | 19 (8%) | 17 (11%) | |

| Moderate | 123 (51%) | 86 (56%) | |

| Severe | 97 (41%) | 51 (33%) |

Missing either physician or patient oral scoring (n=65) so could not be classified.

Missing data for one patient

Oral measures at enrollment

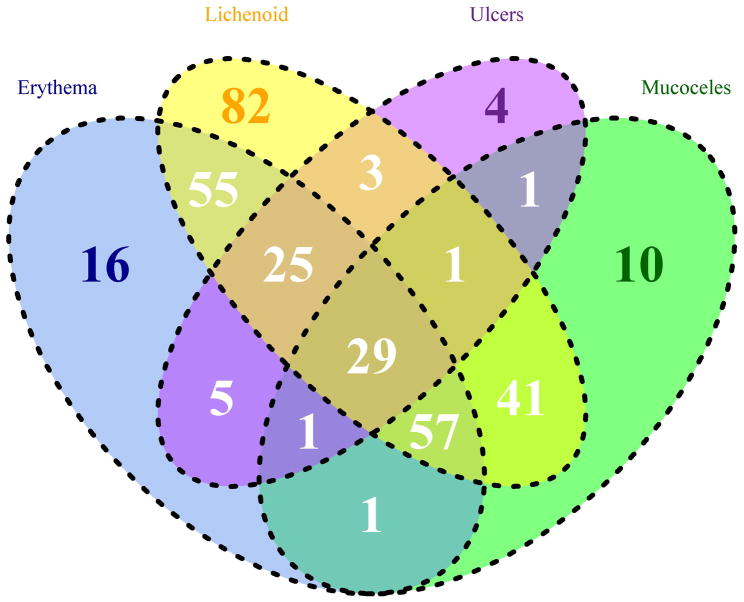

At enrollment, of the 458 patients with cGVHD, 72% (n=331) had objective signs of oral cGVHD (i.e. presence of erythema, lichenoid changes, ulcers or mucoceles; Figure 1). Lichenoid change was the most common objective finding (observed in 293 of 331 cases; 89%), and 28% had only lichenoid involvement without other oral manifestations. Most lichenoid features were rated as mild (185/293, 63%), involving less than 25% of surface areas. Ulcers were the least frequent manifestation, observed in 69 cases (21%); four (6%) presented with only ulcerations. Of those with ulcers, 93% were scored as moderate (≤ 20% of oral surfaces) and 7% as severe (> 20%). Erythema was reported in 189 cases (57%), with 75% categorized as mild, and 7% as severe. Mucoceles were reported in 43% (141 out of 331) of cases. Dryness was reported in 79% of patients, with over half of these with scores of five or less (0–10, 10 “worst dryness”). Mouth pain (defined as worst pain at rest) was reported in 55% of patients, 11% of which were seven or higher. Mouth sensitivity (with eating/drinking) was reported in 69% of patients with oral involvement at enrollment, with 14% of scores being seven or higher.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of objective oral involvement at enrollment (N=331).

Association between scales and instruments

At visits where change in oral cGVHD could be assessed (n=497, 52% of follow-up visits), 50% of clinicians and 56% patients reported improvement, with worsening reported in 4% and 5%, respectively. Agreement between clinician and patient perceived change (improve/stable/worse) was fair (weighted kappa = 0.41), and only 1% of visits had highly discordant changes (improve vs. worse). The associations between changes in individual measurement scales and clinician and patient reported perception of change, adjusted for disease diagnosis and study site, are summarized in Table 2. Compared to stable disease as assessed by clinicians, changes in the NIH clinician overall oral score, the clinician erythema and lichenoid subscores, and the clinician mouth pain scores were associated with both improvement and worsening in the overall clinician reported mouth change score. For example, when clinicians considered oral cGVHD to be improved, the average change score for lichenoid involvement was 0.50 points lower (on a 0–3 scale) than for patients considered stable by clinicians (95% CI 0.36–0.65 points). Similarly, when clinicians assessed a worsening of oral cGVHD compared to stable disease, the average lichenoid change score was 0.46 points higher (95% CI 0.11–0.80 points). Both improvement and worsening in mouth cGVHD, as reported by patients, were associated with changes in the clinician erythema subscore and the patient-reported dryness, pain, sensitivity, and Lee mouth symptom score.

Table 2.

Association between changes in measurement scales and clinician- and patient-reported perception of change (measures with p-value ≤ 0.01 are in bold).

| Clinician Reported | Patient Reported | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Scale | Contrast | Average Change * | Average Change * | ||||

| n | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | n | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Clinician oral score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.39 (−0.52 ~ −0.26) | <.001 | 471 | −0.31 (−0.44 ~ −0.17) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.66 (0.35 ~ 0.97) | <.001 | 471 | 0.24 (−0.06 ~ 0.54) | 0.120 | |

| Clinician oral erythema score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.37 (−0.51 ~ −0.23) | <.001 | 471 | −0.28 (−0.43 ~ −0.13) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.71 (0.36 ~ 1.05) | <.001 | 471 | 0.47 (0.14 ~ 0.8) | 0.006 | |

| Clinician oral lichenoid score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.5 (−0.65 ~ −0.36) | <.001 | 471 | −0.24 (−0.39 ~ −0.08) | 0.003 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.46 (0.11 ~ 0.8) | 0.010 | 471 | 0.31 (−0.03 ~ 0.65) | 0.076 | |

| Clinician oral ulcers score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.32 (−0.5 ~ −0.14) | <.001 | 471 | −0.35 (−0.53 ~ −0.17) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.33 (−0.09 ~ 0.76) | 0.124 | 471 | 0.05 (−0.35 ~ 0.45) | 0.816 | |

| Clinician oral mucoceles score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.15 (−0.34 ~ 0.04) | 0.123 | 471 | −0.18 (−0.38 ~ 0.02) | 0.071 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.33 (−0.13 ~ 0.8) | 0.160 | 471 | 0.18 (−0.25 ~ 0.62) | 0.407 | |

| Clinician mouth pain score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.31 (−0.41 ~ −0.2) | <.001 | 471 | −0.22 (−0.33 ~ −0.1) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | 0.44 (0.19 ~ 0.7) | <.001 | 471 | 0.2 (−0.05 ~ 0.45) | 0.112 | |

| Clinician GI esophagus score change | Improve vs. Stable | 479 | −0.18 (−0.29 ~ −0.07) | 0.001 | 471 | −0.07 (−0.18 ~ 0.04) | 0.208 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 479 | −0.16 (−0.42 ~ 0.1) | 0.233 | 471 | 0.04 (−0.21 ~ 0.28) | 0.772 | |

| Patient mouth dryness score change | Improve vs. Stable | 434 | −0.67 (−1.19 ~ −0.15) | 0.012 | 431 | −1.05 (−1.56 ~ −0.54) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 434 | 1.01 (−0.28 ~ 2.3) | 0.124 | 431 | 2.13 (0.98 ~ 3.27) | <.001 | |

| Patient mouth pain score change | Improve vs. Stable | 433 | −0.97 (−1.45 ~ −0.5) | <.001 | 429 | −1.22 (−1.7 ~ −0.75) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 433 | 0.94 (−0.21 ~ 2.09) | 0.107 | 429 | 1.79 (0.7 ~ 2.88) | 0.001 | |

| Patient mouth sensitivity score change | Improve vs. Stable | 435 | −0.85 (−1.36 ~ −0.33) | 0.001 | 432 | −1.21 (−1.72 ~ −0.7) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 435 | 0.89 (−0.35 ~ 2.14) | 0.158 | 432 | 1.56 (0.4 ~ 2.73) | 0.009 | |

| Patient symptom mouth score change | Improve vs. Stable | 439 | −12.64 (−17.55 ~ −7.73) | <.001 | 435 | −14.65 (−19.53 ~ −9.78) | <.001 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 439 | 14.26 (2.02 ~ 26.51) | 0.023 | 435 | 17.01 (5.96 ~ 28.06) | 0.003 | |

| Patient symptom nutrition score change | Improve vs. Stable | 441 | −2.19 (−4.25 ~ −0.13) | 0.037 | 436 | −2.19 (−4.29 ~ −0.09) | 0.041 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 441 | 6.15 (1.14 ~ 11.16) | 0.016 | 436 | 4.61 (−0.06 ~ 9.28) | 0.053 | |

| Patient weight (kg) change | Improve vs. Stable | 475 | 0.14 (−0.95 ~ 1.23) | 0.799 | 467 | 1.27 (0.16 ~ 2.39) | 0.026 |

| Worsen vs. Stable | 475 | −1.97 (−4.6 ~ 0.65) | 0.140 | 467 | −0.29 (−2.81 ~ 2.23) | 0.821 | |

Average change in serial measurements associated with improvement/worsening of oral cGVHD symptoms as assessed by patients. Linear mixed models with random patient effects were controlled for patient and disease characteristics found to be related to serial change in patient and clinician assessments of oral cGVHD symptoms: disease diagnosis (AML/ALL, CML/CLL, MDS, NHL/HD, Other), study site (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, other sites).

Further multivariable modeling used the continuous (1–8 scale) measurements of perceived change as the response variable, and controlled for multiple serial change measures, as well as disease diagnosis, study site, and clinician assessed global GVHD severity at the prior visit (selected a priori as a control variable). Results from two such models are shown in Table 3: one model predicting clinician perceived change, and one model predicting patient perceived change with the same covariates. Clinician perceived change in oral cGVHD was correlated with serial change in the NIH clinician overall oral score, the erythema and lichenoid subscores, and the pain score. Similarly, patient perceived change in oral cGVHD was correlated with serial change in the Lee mouth symptom score and the NIH erythema subscore. In both models, there was a significant statistical interaction between the erythema and lichenoid subscores.

Table 3.

Results of two multivariable models predicting patient and clinician perceived change in oral cGVHD. Models were adjusted for disease diagnosis, study site, and clinician assessed global GVHD severity at the prior visit.

| Outcome | Clinician perceived Change (1–8), N=455 | Patient perceived change (1–8), N=450 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect (observed range) | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value |

| NIH oral score change | 0.41 (0.18, 0.65) | 0.001 | 0.09 (−0.16, 0.34) | 0.48 |

| Lee mouthsymptom scale change | 0.005 (−0.0004, 0.01) | 0.07 | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | <0.001 |

| NIH erythema change | 0.31 (0.12, 0.50) | 0.002 | 0.34 (0.14, 0.55) | 0.001 |

| NIH lichenoid change | 0.43 (0.24, 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.28) | 0.38 |

| Interaction: erythema change * lichenoid change |

0.21 (0.05, 0.37) | 0.01 | 0.21 (0.04, 0.38) | 0.02 |

| Hopkins pain score change | 0.42 (0.15, 0.69) | 0.003 | 0.15 (−0.14, 0.43) | 0.31 |

There were no significant associations between either patient or clinician reported worsening in oral cGVHD and esophageal score changes or patient weight changes.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter study we prospectively characterized the clinical features of oral cGVHD utilizing the NIH consensus criteria10. A major strength of this cohort is that patients were enrolled primarily because they carried a diagnosis of cGVHD, regardless of oral involvement, and patients were not being referred specifically for a therapeutic intervention. Over half of the patients in this study were enrolled at the time of cGVHD onset, and the median duration of follow-up was 16.5 months, which permitted characterization of clinical features both at the time of enrollment and over time.

Consistent with previous reports that the oral cavity is one of the most frequently affected sites affected by cGVHD, 72% of patients demonstrated some degree of oral involvement at enrollment into the cohort2, 3. This indicates that oral evaluation can be a critical factor in establishing a cGVHD diagnosis as well as potentially determining the need for systemic treatment7. Lichenoid features, one of the “diagnostic” criteria for the diagnosis of cGVHD, was the most frequently reported clinical manifestation with most patients rated as “mild” (involving no more than 25% of the oral mucosa) 7. Oral sensitivity, which is considered the hallmark symptom of oral mucosal cGVHD5, was reported in 69% of patients. During the study period when change in oral cGVHD could be assessed, 50% of clinicians and 56% patients reported improvement, with worsening reported in only 4% and 5%, respectively. Multivariate analyses showed that both clinician reported (NIH oral score, erythema, lichenoid features, Hopkins mouth pain score) and patient-reported measures (Lee mouth symptoms) were associated with clinician and/or patient perceived changes in oral cGVHD. This result suggests that measurement of clinical features alone may not be the most accurate representation of oral cGVHD disease “status”, for example in the context of evaluating response to therapy in a clinical trial, and that reporting of global response is an important measure17, 18.

Several studies to date have evaluated various aspects of the NIH consensus criteria with respect to oral cGVHD assessment. Treister et al., examined the inter- and intra-observer variability in oral cGVHD activity assessment scoring in 24 clinicians composed of transplant oncologists, mid-level providers, and oral medicine specialists using photographic cases that were scored at two time-points using the response criteria19. While overall intraobserver variability was good (kappa score 0.90), overall interobserver variability was moderate to poor and considered unacceptable for the purposes of clinical trials. Mitchell, et al., in a multicenter study assessing the feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the NIH response measures found that the minimal detectable change in the 0–15 oral scale was between 2–3 points, with overall inter-rater variability being modest20. Of note, these results were based on a single 2.5 hour training session suggesting that further training and calibration could further decrease variability. Elad et al., in a study evaluating the construct validity of the oral cGVHD activity assessment instrument found that the total NIH score (0–15) and the sensitivity score (pain with eating) were moderately correlated (r = 0.449), and that the erythema and ulceration scores were the primary drivers of the total score with higher correlations (r = 0.746 and r = 0.926, respectively)21. The authors suggested that the erythema and ulceration features be merged due to their similar patterns to reduce the complexity of this instrument. This could improve the efficiency of the instrument significantly as identifying the presence of ulceration is much more straightforward than assessing the severity of erythema19. In the current analysis ulceration scores were associated with overall improvement, but not disease worsening. The association between ulceration and erythema and mouth pain, as well as the importance of lesion location, has been demonstrated previously22. Since mucoceles were not found to be significantly associated with any relevant measures of oral cGVHD severity from this analysis or the study by Elad et al., and since this feature is distinctive but not diagnostic, this feature may be considered for removal from the assessment instrument.

One of the objectives of this study was to attempt to identify the sentinel features of oral cGVHD that are most highly associated with clinician and patient perceived change to determine the most appropriate measures of disease activity to assess in order to simplify data collection. Lichenoid and erythema subscores (but not mucocele or ulcer subscores) were associated with patient and physician perceived change. Given the strong associations with patient reported symptoms and the overall oral cGVHD severity score (0–3), these measures, along with lichenoid and erythema features and the Hopkins mouth pain score, may be sufficient for assessing oral cGVHD severity and change over time. Given that ulcers are associated with pain and are highly reproducible, the lack of any strong associations in this analysis may in part be related to the fact that ulcers occurred infrequently. The significance of oral ulcers and appropriate weighting of this feature compared with other clinical features deserves further study.

The major strength of this study was the multicenter, prospective nature of the trial that permits generalization of these findings to the larger population of patients with cGVHD requiring systemic immunosuppressive therapy10. The cGVHD Cohort data provide the best measure of the “natural” course of cGVHD, since many patients were observed for long periods of time at several centers but systemic and topical therapies were not controlled by the study. Data were collected in a uniform manner and patients were evaluated at regular time points with extended follow-up.

One major weakness of this study was that systemic and local treatments were not controlled by the study, so we can make no comment on the interventions associated with this improvement6. Another weakness of this study is that the overwhelming majority of patients were adults, so that these findings may not be generalized to the pediatric population. Further investigations are needed to better characterize and evaluate these measures in children. Another concern is that despite the fact that the cGVHD Consortium investigators were experienced clinicians, it is unclear to what extent the instruments were actually used in a consistent manner. Studies assessing inter-rater reliability using photographs or volunteer patients have questioned whether data collected by different evaluators is reliable enough to capture differences20, 23. The fact that some scales did not correlate with patient or clinician-perceived changes may be inherent in the scales or in the way they were completed by clinicians. The format of questions may have also caused some confusion. For example, mouth pain and sensitivity are very different measures and the primary complaint in patients with oral cGVHD is sensitivity, but this distinction may not have been understood by patients. The fact that median sensitivity scores were only slightly higher than pain scores and that 55% of patients reported any pain at rest suggests that these data may not have been collected accurately and/or consistently. It is also possible that confounding oral diseases, such as viral and fungal infections, may have influenced reported symptoms. Given that four patients were reported to have ulcers only without associated lichenoid or erythema changes (Figure 1), this at least suggests that some oral features may have been incorrectly diagnosed as cGVHD (e.g. pseudomembranous candidiasis being mistaken for cGVHD-associated ulceration). Similarly, the clinical appearance of superficial mucoceles can be subtle and diagnosis typically requires examination under very good illumination, such that this feature may have been consistently underdiagnosed23. Lastly, while not a weakness of the study per se, it should be noted that oral cGVHD-associated dental caries are not specifically assessed with these instruments and can be easily overlooked during clinical examination. The consequences of this complication can be potentially devastating and it is therefore critical that clinicians assess for salivary gland cGVHD and recognize and screen for dental findings that include demineralization (chalky white changes) and yellow/brown discoloration of the cervical margins24.

We evaluated proxy measures of swallowing difficulty as well as weight and nutrition to see if these features were associated with oral cGVHD. There was no clear association with any of these measures, suggesting that at least in the aggregate oral cGVHD is not associated with significant limitations in oral intake or swallowing. However, from a clinical standpoint patients with more severe oral mucosal cGVHD can have significant limitations in the ability to eat, and patients with more severe salivary gland cGVHD with significant salivary gland hypofunction can have difficulty swallowing. Given that quality of life (QOL) measures (e.g SF-36 and FACT-BMT) have been shown to be associated with NIH global severity scoring and that changes in QOL measures correlate with changes in patient reported outcomes over time, this suggests that oral-specific quality of life measures may be critical endpoints to assess in the context of clinical trials25, 26. This is further supported by the recent finding that overall and organ-specific responses do not correlate well with quality of life measures27.

The Chronic GVHD Consortium represents a collaborative effort and novel opportunity to study and measure the natural course of GVHD under conditions of standard medical management. It was within this framework that we were able to characterize the oral features of chronic GVHD, and more importantly identify those features that are best correlated with perceived symptom changes. Our findings suggest that the oral instruments for assessing cGVHD as outlined by the NIH Consensus Conference can be simplified and that certain measures that are not associated with change in symptoms can likely be eliminated. It is also evident that adequate training of clinicians in the appropriate use of the NIH instruments is critical in order to collect consistent and meaningful clinical data. Prospective evaluation in the context of dedicated clinical trials of systemic and ancillary therapies will be necessary to ensure the appropriateness and utility of any instrument revisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants CA118953 and CA163438.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at BMT’s website

Author contributions: SP, DW, JP, JP, PM, YI, MA, MF, DJ, MJ, SA, SJL, CC contributed clinical data; XC and BFK performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; NT, CC and SJL designed research and drafted the manuscript; and all authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical review of the manuscript.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9(4):215–33. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai S, Jagasia M, Storer B, Chai X, Pidala J, Cutler C, et al. Global and organ-specific chronic graft-versus-host disease severity according to the 2005 NIH Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;118(15):4242–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flowers ME, Parker PM, Johnston LJ, Matos AV, Storer B, Bensinger WI, et al. Comparison of chronic graft-versus-host disease after transplantation of peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow in allogeneic recipients: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Blood. 2002;100(2):415–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imanguli MM, Alevizos I, Brown R, Pavletic SZ, Atkinson JC. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Oral Dis. 2008;14(5):396–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schubert MM, Correa ME. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52(1):79–109. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, Bolanos-Meade J, Treister NS, Gea-Banacloche J, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(4):375–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin PJ, Weisdorf D, Przepiorka D, Hirschfeld S, Farrell A, Rizzo JD, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. Design of Clinical Trials Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(5):491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, Mitchell S, Jacobsohn D, Cowen EW, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(3):252–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rationale and design of the chronic GVHD cohort study: improving outcomes assessment in chronic GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(8):1114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsohn DA, Chen AR, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Anders V, Bolanos-Meade J, et al. Phase II study of pentostatin in patients with corticosteroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):4255–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(8):444–52. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleiss J, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner JC, Luo Z, Roman LA. Fixed effects, random effects and GEE: what are the differences? Stat Med. 2009;28(2):221–39. doi: 10.1002/sim.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzmaurice GMLN, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. 2. Wiley; Hoboken: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laird NM. Missing data in longitudinal studies. Stat Med. 1988;7(1–2):305–15. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavletic SZ, Lee SJ, Socie G, Vogelsang G. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: implications of the National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(10):645–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer JM, Lee SJ, Chai X, Storer BE, Flowers ME, Schultz KR, et al. Poor Agreement between Clinician Response Ratings and Calculated Response Measures in Patients with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treister NS, Stevenson K, Kim H, Woo SB, Soiffer R, Cutler C. Oral chronic graft-versus-host disease scoring using the NIH consensus criteria. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;16(1):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell SA, Jacobsohn D, Thormann Powers KE, Carpenter PA, Flowers ME, Cowen EW, et al. A multicenter pilot evaluation of the National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) therapeutic response measures: feasibility, interrater reliability, and minimum detectable change. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(11):1619–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elad S, Zeevi I, Or R, Resnick IB, Dray L, Shapira MY. Validation of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) scale for oral chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;16(1):62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treister NS, Cook EF, Jr, Antin J, Lee SJ, Soiffer R, Woo SB. Clinical evaluation of oral chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(1):110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treister NS, Stevenson K, Kim H, Woo SB, Soiffer R, Cutler C. Oral chronic graft-versus-host disease scoring using the NIH consensus criteria. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(1):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellarin P, Stevenson K, Biasotto M, Yuan A, Woo SB, Treister NS. Extensive dental caries in patients with oral chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(10):1573–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, Majhail N, Weisdorf DJ, Pavletic S, et al. Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2011;117(17):4651–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pidala J, Kurland BF, Chai X, Vogelsang G, Weisdorf DJ, Pavletic S, et al. Sensitivity of changes in chronic graft-versus-host disease activity to changes in patient-reported quality of life: results from the Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Consortium. Haematologica. 2011;96(10):1528–35. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.046367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inamoto Y, Martin PJ, Chai X, Jagasia M, Palmer J, Pidala J, et al. Clinical Benefit of Response in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.