Abstract

The social organization of giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) imposes a high-cost reproductive strategy on bulls, which adopt a ‘roving male’ tactic. Our observations on wild giraffes confirm that bulls indeed have unsynchronized rut-like periods, not unlike another tropical megaherbivore, the elephant, but on a much shorter timescale. We found profound changes in male sexual and social activities at the scale of about two weeks. This so far undescribed rutting behaviour is closely correlated with changes in androgen concentrations and appears to be driven by them. The short time scale of the changes in sexual and social activity may explain why dominance and reproductive status in male giraffe in the field seem to be unstable.

Keywords: giraffe, mating period, rut, faecal androgens, non-invasive hormone monitoring, Hwange National Park

1. Introduction

Variation in male mating tactics within a species can largely be explained by the spatial and temporal distribution of females, and males commonly adopt a high-cost roving tactic in populations where mates are unpredictably distributed and periods of receptivity limited in time [1]. Furthermore, variation in male reproductive tactics can be expected to result from variation in individual capability to secure mates as well as adjustments to the costs of potential physical confrontation, particularly among roving males [1,2]. The pivotal role of androgens in male reproductive behaviour is well documented [3], with males often undergoing androgen-dependent morphological changes during well-defined breeding seasons. Shifts in alternative reproductive tactics are also hypothesized to be under proximate hormonal control [3,4]. However, very little is known about the endocrine control of reproduction-related male roving behaviour.

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) social system is usually based on loose associations of individuals; older adult males tend to be solitary, and roving [5], which can be expected to have high costs, at least in terms of time. The development of ossicones, additional bone structures on the forehead, and clearly visible neck musculature as males age, allows bulls to be categorized into three different classes (A, B and C; figure 1), with Class-A bulls generally being the most dominant [6]. Younger and subordinate males may adopt alternative, less-competitive reproductive tactics, as seen in other vertebrates [2,7]. To our knowledge, testicular endocrine function in giraffe bulls has not yet been studied in vivo, but studies on culled animals showed that androgen concentrations are correlated with age [8]. However, the same study mentions that androgen levels vary greatly between individuals, which remains unexplained.

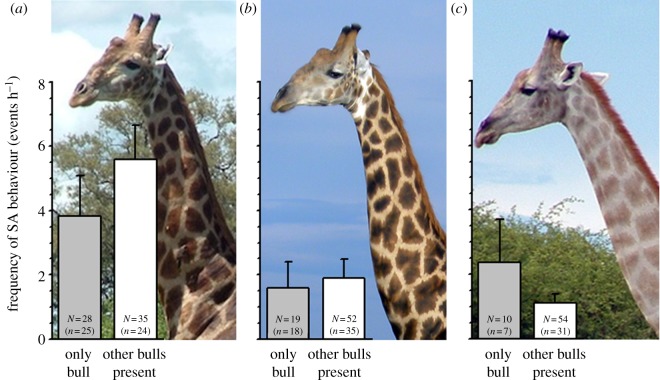

Figure 1.

(a–c) Pictures of a Classes-A, -B and -C bull, respectively (Photo credit: P.A. Seeber). Sexually active (SA) behaviours (mean + s.e.m.) observed in different classes of giraffe bulls, divided by the state of the focal bull's social association (‘N’ is the sample size, the number of focal animal observations; ‘n’ is the number of different bulls observed). (Online version in colour.)

This study, carried out in the Hwange area of Zimbabwe, aimed to describe the social and sexual behaviour of male giraffes. We report here new results on the endocrine basis for their highly flexible sexual behaviour and suggest that giraffe bulls have unsynchronized rut-like periods, as other ‘roving male’ species, e.g. elephants, but that they last only days, not months, presumably because of the high costs involved.

2. Material and methods

Fieldwork was conducted in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, from March to May 2011. The Park is situated in the province of Matabeleland North in western Zimbabwe on the Botswana border and covers approximately 14 700 km2 of diverse habitat. In total, 188 h of observations were conducted on 59 days (range 0.5–5.5 h per day) from about 50 to 100 m distance, and a total of 1107 giraffe sightings were made. Seventy-three bulls were individually identified by their unique pelage pattern [9] and classified into three age classes A, B and C, based on physical appearance, that is body size, musculature of the neck, shape of skull and ossicones, as described by Pratt & Anderson [6].

Predefined behavioural patterns of sexual activity (investigating, urine testing, mate guarding and mating attempt) were observed using focal animal sampling and ad libitum sampling [9]. Respective behaviours were recorded by all-occurrence sampling [10]. During every observation, group size and group composition (number and sex of adult and subadult individuals) were recorded. Bulls were considered to be sexually active if at least one of the defined sexual behavioural patterns was seen during a given observation period. Behavioural patterns were recorded as events and subsequently transferred into the frequency of observed sexual activity per hour (electronic supplementary material, table 1).

A total of 66 faecal samples from 39 known, different bulls were collected within 20 min after defaecation. Samples were considered to be from a sexually active individual if the animal showed a sexual behavioural pattern at least once during a 72 h time window around collection (electronic supplementary material, table 2). Samples were dried in an oven at approximately 50°C for about 24 h until complete dryness. The dried material was then pulverized and sieved in order to remove undigested fibrous material [11]. Approximately 0.1 g of the faecal powder was then extracted with 80% ethanol in water (3 ml) [12]. The resulting extracts were measured for immunoreactive androgen metabolites (electronic supplementary material, table 2) using an enzyme immunoassay for epiandrosterone [13], which have been shown to reliably reflect testicular endocrine function in a variety of mammalian species [12]. The epiandrosterone assay used an antibody against 5α-androstane-3α-ol-17-one-HS and 5α-androstane- 3, 17-dione-thioether conjugated with biotin as a label [13]. Cross-reactivities of the antibody used are described in Ganswindt et al. [12]. Assay procedures followed the protocols published by Ganswindt et al. [12]. Serial dilutions of extracted faecal samples gave displacement curves that were parallel to the respective standard curve. Sensitivity (90% binding) of the assay was 5 ng g−1. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation determined by repeated measurements of high and low value quality controls ranged between 3.5 and 11.6%.

Differences in median faecal androgen metabolite (FAM) levels between two sets of data were examined by either t-tests or Mann–Whitney rank sum tests. Tests were two-tailed, with an α level of significance set at 0.05. All pairwise multiple comparison procedures were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc analysis using Tukey test, with a Bonferroni correction. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS v. 19.0.0 and 20.0.

3. Results

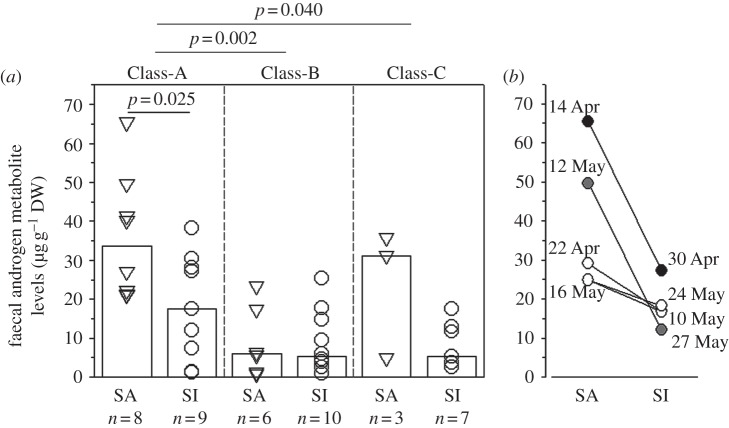

Class-A males show high frequencies of sexual activity (fSA) and the presence of other males seems to stimulate this behaviour, whereas Classes-B and -C bulls show clearly lower fSA, and for the Class C bulls, the presence of other males seems to inhibit sexual activity (figure 1). Median FAM levels of Class-A bulls are significantly higher than FAM concentrations of Class-B bulls (F2 = 7.43, n = 14,15,10, p = 0.002, post hoc p = 0.002) and a clear trend of higher FAM levels for Class-A bulls were found when compared with Class-C males (p = 0.04; figure 2a), but values are extremely variable within classes (FAM ranges for Class-A: 0.9–65.4 µg g−1 DW, Class-B: 0.7–29.3 µg g−1 DW, Class-C: 2.5–35.8 µg g−1 DW). When grouped by sexual behaviour, sexually active Class-A bulls have significantly higher median FAM levels than inactive individuals of the same class (t = 2.48, d.f. = 15, p = 0.025; figure 2a). Although median FAM levels of sexually active individuals of the other two classes are on average higher than FAM concentrations of inactive Classes-B and -C ones (figure 2a), the differences are not significant.

Figure 2.

(a) FAM concentrations derived from 39 individuals. Each symbol represents the median hormone value of an individual which was either sexually active (SA) or inactive (SI). The bars show the medians of the individual medians. Statistically significant differences between reproductive states within a class as well as between classes irrespective of the reproductive state are indicated. (b) Individual FAM levels from three Class-A giraffe bulls (different colours (white, grey and black) indicate different individuals). Each dot represents the hormone value of an individual showing either SA or SI. Values where a transition from SA to SI occurred are connected by a line.

Within the group of Class-A males, individual males switching between periods of sexual activity/inactivity within days or weeks could be observed (figure 2b), and these switches from sexual activity to inactivity were clearly correlated with sharp declines in FAM concentrations.

4. Discussion

The highest frequency of sexual activity was observed for Class-A bulls, with the presence of other males stimulating sexual active behaviour. Class-A bulls also have on average higher FAM levels compared with Classes-B and -C bulls. Although such a positive correlation between age and androgens has already been shown for other male mammals, like bison bulls [14], endocrinological changes in relation to age are sometimes difficult to reveal as dominance and age are often closely related [15].

Male giraffes of all classes may show sexually active behaviours, and these active males have on average higher FAM concentrations than inactive males of the same class, a likely link also recognized in other male mammals [14,16,17]. However, giraffe males switch between sexually active/inactive phases at the scale of about two weeks (at least in Class-A), and their FAM levels change accordingly, which suggests that giraffe males have rut-like periods but at a much shorter timescale than, for example, elephants, as these other tropical megaherbivores show periods of heightened sexual activity, known as musth, for up to several months [18]. An alternative explanation is that the giraffe adapted their sexual behaviours to challenging social structures or environmental conditions, subsequently reflected in respective changes of associated endocrine patterns [19–21].

The short-term changes in sexual activity and associated social interactions seen in giraffe bulls may explain why dominance and reproductive status in male giraffes in the field seem unstable. These findings suggest that giraffes may have a unique breeding system. Further work should aim at testing these ideas with long-term observations on males and, in parallel, on females. In particular, what is the frequency of rutting activity in bulls, and how is this linked to local male dominance and reproductive success? Furthermore, the temporal relationship between endocrinological and behavioural changes needs to be studied in detail to understand the role of different hormones (androgens and glucocorticoids) as drivers of the flexible behaviour seen in these animals. In this regard, the impact of socio-ecological conditions on reproductive endocrine function [20,21] has to be adequately taken into account as already stated above, because results from giraffes in confined habitats living in stable social groups with an established dominance hierarchy might differ from those of giraffes roaming under more natural conditions.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Parks and Wildlife Management Authority for permission to conduct this research and to publish this paper, and S.B. Ganswindt for expert help in laboratory techniques.

Funding statement

The project was supported by the University of Pretoria, Novartis/South African Veterinary Foundation Wildlife Research Fund, Giraffe Conservation Foundation and by the CNRS INEE Zones Atelier program.

References

- 1.Clutton-Brock TH. 1989. Mammalian mating systems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 236, 339–372 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1989.0027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasmussen HB, Okello JBA, Wittemyer G, Siegismund HR, Arctander P, Vollrath F, Douglas-Hamilton I. 2008. Age- and tactic-related paternity success in male African elephants. Behav. Ecol. 19, 9–15 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arm093) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen HB, Ganswindt A, Douglas-Hamilton I, Vollrath F. 2008. Endocrine and behavioural changes in male African elephants: linking hormone changes to sexual state and reproductive tactic. Horm. Behav. 54, 539–548 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.05.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebe RH, Williams LE, Abee CR, Yeoman RR, Diamond EJ. 1988. Seasonal changes in serum dehydroepiandrosterone, androstenedione, and testosterone levels in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis boliviensis). Am. J. Primatol. 14, 285–291 (doi:10.1002/ajp.1350140309) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bercovitch FB, Bashaw MJ, del Castillo SM. 2006. Sociosexual behavior, male mating tactics, and the reproductive cycle of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). Horm. Behav. 50, 314–321 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt DM, Anderson VH. 1885. Giraffe social behaviour. J. Nat. Hist. 19, 771–781 (doi:10.1080/00222938500770471) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira RF, Taborsky M, Brockman HJ. 2008. Alternative reproductive tactics: an integrative approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall-Martin AJ, Skinner JD, Hopkins BJ. 1978. The development of the reproductive organs of the male giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis. Reprod. Fertil. 52, 1–7 (doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0520001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shorrocks B, Croft DP. 2009. Necks and networks: a preliminary study of population structure in the reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata de Winston). Afr. J. Ecol. 47, 374–381 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00984.x) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin P, Bateson P. 2000. Measuring behaviour: an introductory guide, 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fieß M, Heistermann M, Hodges JK. 1999. Patterns of urinary and fecal steroid excretion during the ovarian cycle and pregnancy in the African elephant (Loxodonta africana). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 115, 76–89 (doi:10.1006/gcen.1999.7287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganswindt A, Heistermann M, Borragan S, Hodges JK. 2002. Assessment of testicular endocrine function in captive African elephants by measurement of urinary and fecal androgens. Zoo Biol. 21, 27–36 (doi:10.1002/zoo.10034) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palme R, Möstl E. 1993. Biotin-streptavidin enzyme immunoassay for the determination of oestrogens and androgens in boar faeces. In Advances of steroid analysis ‘93 (ed. Görög S.), pp. 111–117 Budapest, Hungary: Akadémiai Kiadó [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooring MS, Patton ML, Lance VA, Hall BM, Schaad EW, Fortin SS, Jella JE, McPeak KM. 2004. Fecal androgens of bison bulls during the rut. Horm. Behav. 46, 392–398 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.03.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganswindt A, Heistermann M, Hodges JK. 2005. Physical, physiological and behavioural correlates of musth in captive African elephants (Loxodonta africana). Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 78, 505–514 (doi:10.1086/430237) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganswindt A, Rasmussen HB, Heistermann M, Keith J. 2005b. The sexually active states of free-ranging male African elephants (Loxodonta africana): defining musth and non-musth using endocrinology, physical signals, and behavior. Horm. Behav. 47, 83–91 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschenhauser K, Oliveira RF. 2006. Social modulation of androgens in male vertebrates: meta-analyses of the challenge hypothesis Anim . Behav. 71, 265–277 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.04.014) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poole JH. 1987. Rutting behavior in African elephants: the phenomenon of musth. Behaviour 102, 283–316 (doi:10.1163/156853986X00171) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingfield JC, Hegner RE, Dufty AM, Ball GF. 1990. The ‘Challenge Hypothesis’: theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone secretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies. Am. Nat. 136, 829–846 (doi:10.1086/285134) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veasey JS, Waran NK, Young RJ. 1995. On comparing the behaviour of zoo housed animals with wild conspecifics as a welfare indicator, using the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) as a model. Anim. Welf. 5, 139–153 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morato RG, Conforti VA, Azevedo FC, Jacomo AT, Silveirea L, Sana D, Nunes AL, Guimaraes MA, Barnabe RC. 2001. Comparative analyses of semen and endocrine characteristics of free-living versus captive jaguars (Panthera onca). Reproduction 122, 745–751 (doi:10.1530/rep.0.1220745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]